Abstract

Introduction

‘Green spaces’ such as public parks are regarded as determinants of health, but evidence from tends to be based on cross-sectional designs. This protocol describes a study that will evaluate a large-scale investment in approximately 5280 hectares of green space stretching 27 km north to south in Western Sydney, Australia.

Methods and analysis

A Geographic Information System was used to identify 7272 participants in the 45 and Up Study baseline data (2006–2008) living within 5 km of the Western Sydney Parklands and some of the features that have been constructed since 2009, such as public access points, advertising billboards, walking and cycle tracks, BBQ stations, and children's playgrounds. These data were linked to information on a range of health and behavioural outcomes, with the second wave of data collection initiated by the Sax Institute in 2012 and expected to be completed by 2015. Multilevel models will be used to analyse potential change in physical activity, weight status, social contacts, mental and cardiometabolic health within a closed sample of residentially stable participants. Comparisons between persons with contrasting proximities to different areas of the Parklands will provide ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ groups within a ‘quasi-experimental’ study design. In line with expectations, baseline results prior to the enhancement of the Western Sydney Parklands indicated virtually no significant differences in the distribution of any of the outcomes with respect to proximity to green space preintervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained for the 45 and Up Study from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Western Sydney Ethics Committee. Findings will be disseminated through partner organisations (the Western Sydney Parklands and the National Heart Foundation of Australia), as well as to policymakers in parallel with scientific papers and conference presentations.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, SOCIAL MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A key strength of this study is the longitudinal design that leverages a major local change in green space provision.

Another important strength is the range of health and behaviour variables that can be examined within a large sample of participants.

The study is limited by self-report outcome data and that participants are aged 45 years and older, so future research that focuses on younger adults, youths and children within the same context is also warranted.

Introduction

‘Green spaces’ such as public parks are increasingly regarded as important correlates of cardiovascular health by the scientific community.1 This is based on mounting evidence not only from small-scale experiments,2 3 but also large observational studies.4–6 As a result, there is also rising interest among urban planning and health policy decision makers in the opportunities for constructing and targeting green spaces to make more ‘liveable’ neighbourhoods that actively promote mental and cardiometabolic health, physical recreation and overall quality of life.7 8

A challenge with this wave of optimism, however, is the quality of the observational evidence underpinning it.9 The vast majority of studies have been cross-sectional, which means that putative interventions, such as an increase in the quantity or quality of green space available locally, cannot be rigorously evaluated for their impact on health. Even with multivariate adjustment for income and other factors which determine where a person can choose to live, unmeasured(able) variables such as a person's preference for living in a greener neighbourhood cannot be ruled out. This may lead to the reporting of inaccurate (or even spurious) associations with health and inappropriate policy recommendations.

The observational evidence on green space and health is at a crossroads. More emphasis is required from studies using designs that harness temporal as well as spatial dimensions in order to provide insights on how much and/or what type of green space matters for what (ie, participation in physical activity), when (ie, at what period in the life course) and for whom (ie, particular sociodemographic groups).9 A one-size-fits-all prescription of green space seems unlikely and both scientific research and policy needs to engage with that potentially inconvenient level of complexity. In particular, the evaluation of natural experiments and controlled trials in order to enhance the quality of evidence available for decision makers is needed.10 Such longitudinal studies should (1) measure the association between a change in exposure to green space on a change in health outcome and (2) have more rigorous controls for possible confounding, such as the restriction of a sample to people whose exposure changes around them,11 rather than as a result of relocation that is likely to be highly entwined with health selection.12

To build more robust evidence in this area, investigators at Western Sydney University and the University of Wollongong (Australia) formed a partnership with the Western Sydney Parklands Trust and obtained funding from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (ID 100161) to devise the ‘Western Sydney Parklands Longitudinal Study’ (WSPLS). The aim of the WSPLS is to assess, longitudinally, the extent that cardiovascular risk factors among middle-to-older aged adults are influenced by enhanced local green space provision.

In Western Sydney, a socioeconomically and culturally diverse region of Australia home to over two million residents, the New South Wales (NSW) Government invested in the development of approximately 5280 hectares of green space stretching 27 km north to south and spanning three local government areas: Blacktown, Fairfield and Liverpool from 2009 onwards. Communities living across this area are known to experience significant levels of socioeconomic disadvantage and poorer health, such as a high risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus13 and psychological distress.14 The ‘Western Sydney Parklands’ will become the largest urban parkland in Australia and among the largest globally. Much of the land in 2009 comprised residential or vacant land use. It is intended that the investment will change this composition to approximately 40% dedicated bushland, 25% sport and recreation, 22% long-term infrastructure (eg, water storage), 10% urban farming, 2% business hubs, and 1% tourism. The development of the Western Sydney Parklands is an example of a large-scale investment in green space that could be potentially regarded as an intervention for physical activity, mental and cardiometabolic health within proximity to communities with significant health need. In this paper, we outline a study protocol used for a quasi-experimental design to evaluate the health impacts of this natural experiment.

Methods and analysis

Data

A Geographic Information System (GIS) comprising geocoded land-use data was provided to the investigator team by the Western Sydney Parklands. This included the grounds of the Western Sydney Parklands and some of the features that have been constructed since 2009, such as the locations of public access points, advertising billboards, walking and cycle tracks, BBQ stations, and children's playgrounds. These data were linked to information on a range of health outcomes, health-related behaviour and possible confounders reported by participants in the 45 and Up Study baseline survey. Detailed information on the development of the 45 and Up Study is published elsewhere.15 In brief, 267 102 persons aged 45–106 years (mean age=62.8, SD=11.2) responded to a self-complete baseline questionnaire that was delivered between 2006 and 2008. Participants had been randomly selected from the Medicare Australia database (the national provider of universal health insurance), with a response of 18%. While this response is low and there was greater participation among more socioeconomic advantaged persons, previous work has suggested that findings from the 45 and Up Study compare favourably with more representative population health surveys.16 The 45 and Up Study has been previously used to analyse a range of health and behavioural outcomes in relation to green space exposure,5 17–21 as well as other spatial phenomena.11 13 22–25 The second wave of data collection was initiated in 2012 with a follow-up questionnaire mailed to over 40 000 participants and a further 86 250 contacted by late 2013. All other remaining participants will be resurveyed in 2014 and 2015. The University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee approved the 45 and Up Study.

Sample

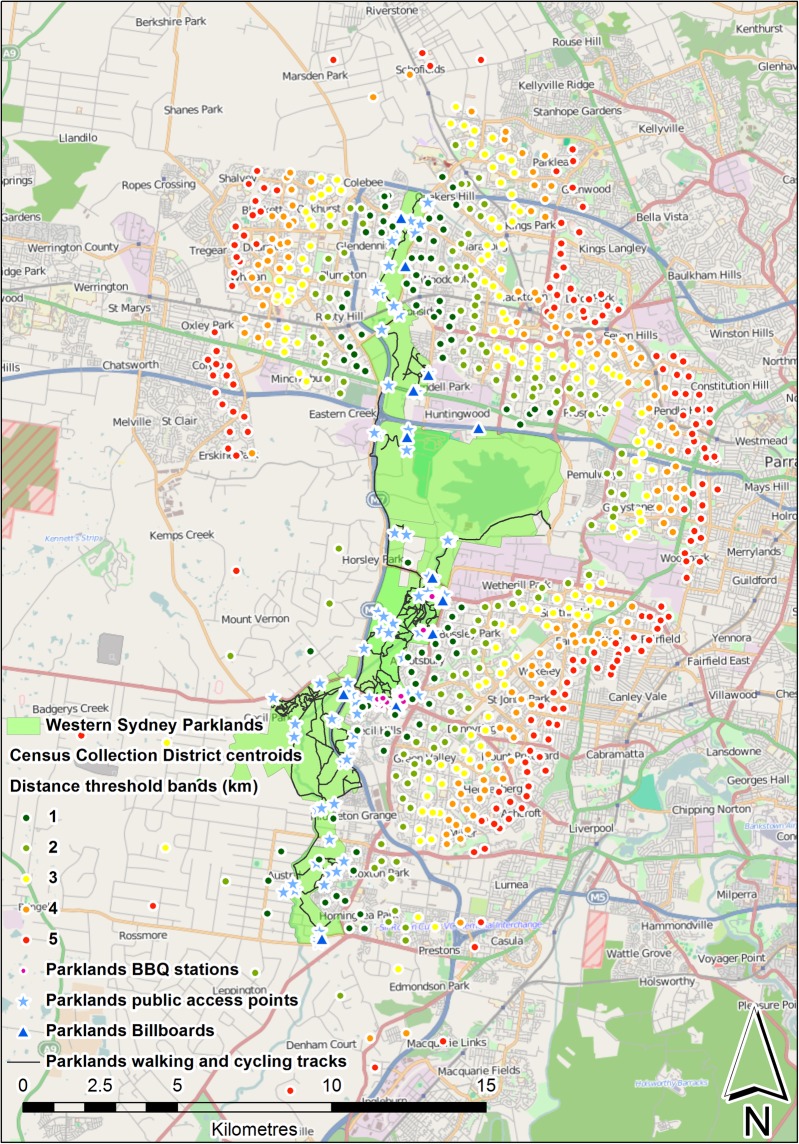

The baseline sample for the WSPLS was initially selected from participants in the 45 and Up Study who resided up to 5 km Euclidean distance (as the crow flies) from any point of the Western Sydney Parklands (figure 1). As appropriate data become available, this sampling may be modified to take into account road and footpath network distance to the Western Sydney Parklands, as this is likely to be more indicative of the journeys people will take to access the green space. A total of 7272 participants were selected. These participants were nested within 624 ‘Census Collection Districts’ (12 participants on average per Census Collector District, ranging from 1 to 156). A GIS was used to classify all participants in the sample by their respective Collection Districts of residence into 1 km proximity bands as the most basic definition of ‘exposure’ to the Western Sydney Parklands. As is evident from figure 1, features of the Parklands that could promote certain health outcomes and health-related behaviours, such as walking paths and BBQ stations, are not randomly distributed. Similarly, there is a spatial patterning of features that offer no direct health benefit but may be effect measure modifiers through influencing the odds of whether participants visit the Western Sydney Parklands or not, such as the locations of advertising billboards. As such, definitions of exposure will be modified according to the hypothesised causal pathway being tested. Mental health, for example, may be influenced by living near any part of the Parklands, but especially areas where people can be social, such as BBQ stations, picnic tables and playgrounds. Conversely, the power for green space to influence physical recreation will likely depend on the locations of features that support active lifestyles, such as walking paths. Table 1 reports how the definition of exposure in the baseline sample could be potentially modified accordingly. Approximately 61% of participants who lived within 1 km of any part of the Parklands (n=543), for example, lived 10 km or more from the nearest Parklands BBQ station. Proximity to other potentially health-relevant sites within the Western Sydney Parklands such as picnic tables, playgrounds, gardens and walking and cycling tracks will also be measured.

Figure 1.

Western Sydney Parklands, park features and proximity of Census Collection Districts.

Table 1.

Proximity to selected features which are part of the Western Sydney Parklands

| Proximity to any part of the Western Sydney Parklands (km) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| N | 891 | 1525 | 1516 | 1596 | 1724 |

| Proximity to public access points (km) | |||||

| 1 | 661 (74.2%) | 13 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 3 | 200 (22.4%) | 1159 (76.0%) | 767 (50.6%) | 16 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 5 | 30 (3.4%) | 162 (10.6%) | 442 (29.2%) | 1092 (68.4%) | 707 (41.0%) |

| >10 | 0 (0.0%) | 191 (12.5%) | 307 (20.3%) | 488 (30.6%) | 1017 (59.0%) |

| Proximity to walking and cycling tracks (km) | |||||

| 1 | 613 (68.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 3 | 253 (28.4%) | 1328 (87.1%) | 1062 (70.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 5 | 25 (2.8%) | 197 (12.9%) | 417 (27.5%) | 1386 (86.8%) | 991 (57.5%) |

| >10 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 37 (2.4%) | 210 (13.2%) | 733 (42.5%) |

| Proximity to BBQ stations (km) | |||||

| 1 | 186 (20.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 3 | 101 (11.3%) | 396 (26.0%) | 160 (10.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 5 | 61 (6.8%) | 77 (5.0%) | 145 (9.6%) | 420 (26.3%) | 180 (10.4%) |

| >10 | 543 (60.9%) | 1052 (69.0%) | 1211 (79.9%) | 1176 (73.7%) | 1544 (89.6%) |

| Proximity to advertising billboards (km) | |||||

| 1 | 302 (33.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 3 | 520 (58.4%) | 1120 (73.4%) | 404 (26.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 5 | 66 (7.4%) | 353 (23.1%) | 874 (57.7%) | 1088 (68.2%) | 363 (21.1%) |

| >10 | 3 (0.3%) | 52 (3.4%) | 238 (15.7%) | 508 (31.8%) | 1361 (78.9%) |

What outcomes will be measured?

A range of self-reported health outcomes and health-related behaviours at baseline and follow-up will be selected for analysis in line with existing scientific evidence.1 Health outcomes will include an indicator of psychological well-being as measured by the Kessler 10 scale (K10), which screens for symptoms of psychological distress experienced over the 4 weeks prior to survey completion.26 Questions in the K10 cover feelings of tiredness for no reason, nervous, hopeless, restless, depressed, sad and worthless. Participants had five choices for each of the 10 questions (none of the time=1, a little of the time=2, some of the time=3, most of the time=4, all of the time=5) and these will be summed to give the overall score. In line with previous work,20 23 27 a binary variable will be constructed with scores of 22 and over identifying participants at high risk of psychological distress.28

Physical functioning will be measured using the Medical Outcomes Study Physical Functioning Scale (MOS-PF).29 30 The MOS-PF is a 10-item scale covering vigorous activities (eg, climbing stairs) to more basic actions related to day to day living (eg, bathing). Physical health will also be measured using body mass index (BMI), already shown to be related to green space in these data at baseline17 and derived from self-reported height and weight, with overweight (BMI 25–29.9) and obesity (BMI >30) determined by WHO criteria.31 Comparisons between this measure of BMI and an objective measure with a subsample of this data set were favourable.32 Incidence of doctor-diagnosed cardiometabolic diseases such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease and diabetes will also be assessed via self-report.

Key mediating variables between green space and mental and cardiometabolic health outcomes are those relating to physical recreation. These behavioural characteristics include self-reported responses describing walking and participation in moderate and vigorous physical activities, as well as questions on approximate time spent sitting, standing, watching television or computer screens, and sleep duration. Physical activity will be assessed using responses to questions derived from the Active Australia Survey:33 ‘How many times did you do each of these activities last week?’ Participants could indicate moderate (eg, gentle swimming) and vigorous (eg, jogging) forms of activity separately, as well as walking. The Active Australia Survey has been shown to have a satisfactory level of test-retest reliability,34 and cross-sectional analysis of baseline data has previously shown association between the derived variables and an objective measure of green space exposure.18

Improvements in green space provision may also stimulate enhancements in social networking.35 Three out of four items will be selected from the shortened version of the Duke Social Support Index36 in this regard: ‘How many times in the last week did you…(1) spend time with friends or family who do not live with you’; (2) ‘you go to meetings of social clubs, religious groups or other groups you belong to?’ and (3) ‘How many people outside your home, but within one hour of travel, do you feel you can depend on or feel very close to?’ The fourth question on telephone conversations is less relevant and, therefore, will be considered as a form of negative control.37

Descriptive analyses reported in tables 2 and 3 show that there were virtually no significant differences in the distribution of any of these outcomes with respect to proximity to any part of the Western Sydney Parklands in the baseline sample. This can be expected as all of the enhancements occurred from 2009 onwards; after people participated in the 45 and Up Study baseline.

Table 2.

Patterning of health outcomes at baseline, by proximity to the Parklands

| Proximity to any part of the Western Sydney Parklands (km) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| N | 891 | 1525 | 1516 | 1596 | 1724 |

| Mean | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| K10 >22 | 17% | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) |

| Per cent missing | 2.69 | 3.21 | 3.03 | 3.57 | 3.54 |

| Self-rated quality of life | 3% | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.3) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.6) | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.2) |

| Per cent missing | 6.51 | 7.15 | 8.64 | 8.58 | 6.9 |

| Overweight and obese | 68% | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

| Per cent missing | 8.08 | 8.33 | 9.04 | 9.15 | 9.05 |

| Diabetes | 13% | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6)* | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.6) |

| Per cent missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High blood pressure | 37% | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5)* | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| Per cent missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CVD | 11% | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7)* |

| Per cent missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) | |||||

| Physical functioning | 17.86 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5)* | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4)* |

| Per cent missing | 19.98 | 20.98 | 22.82 | 23.37 | 24.42* |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; from distance to Parklands <1 km.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; K10, Kessler 10 scale.

Table 3.

Patterning of health-related behaviours at baseline, by proximity to the Parklands

| Proximity to any part of the Western Sydney Parklands (km) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| N | 891 | 1525 | 1516 | 1596 | 1724 |

| Mean | Rate ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Walk | 5.44 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

| Per cent missing | 6.29 | 7.02 | 7.85 | 8.21 | 8.18 |

| Moderate PA | 4.36 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

| Per cent missing | 12.91 | 11.8 | 13.65 | 14.29 | 13.98 |

| Vigorous PA | 1.48 | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Per cent missing | 18.97 | 19.54 | 21.11 | 22.12 | 21.46 |

| Screen time (hours) | 4.38 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) |

| Per cent missing | 4.71 | 4.59 | 5.28 | 5.76 | 5.51 |

| Social visits | 3.95 | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.1) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2)** | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2)* |

| Per cent missing | 3.82 | 4.33 | 4.22 | 5.01 | 4.58 |

| Social groups | 1.47 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| Per cent missing | 6.4 | 6.62 | 6.79 | 8.15 | 8 |

| People I can depend on | 6.51 | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

| Per cent missing | 5.95 | 5.38 | 4.55 | 6.58 | 6.15 |

| Coefficient (95% CI) | |||||

| Sitting time (hours) | 5.76 | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.3) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) | 0.0 (-−0.3 to 0.2) |

| Per cent missing | 7.86 | 8.07 | 9.56 | 11.34* | 9.45 |

| Standing time (hours) | 4.82 | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) |

| Per cent missing | 11 | 10.95 | 13.65 | 14.97* | 13.98* |

| OR (95% CI) | |||||

| 6 h sleep or less | 84% | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) |

| Per cent missing | 4.26 | 3.41 | 3.63 | 4.7 | 4.47 |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; *** p<0.001; from distance to Parklands <1 km.

PA, physical activity.

Epidemiological study design specifications to minimise confounding

The major source of confounding will include health selective migration.12 This is when persons who are already healthier and more likely to use green space for health-enhancing reasons purposefully move to neighbourhoods located within close proximity of the Western Sydney Parklands, in order to benefit from the convenience of easy access to nature. Multiple specifications will be made to minimise this form of bias. First, the prospective design will focus attention exclusively on persons who lived close to the Parklands before investment and enhancements began. Tracking health outcomes and health-related behaviours among this ‘closed’ sample through time will, therefore, help identify the impacts of changes in the green space located nearby. Second, drawing comparisons between persons with contrasting proximities to different areas of the Parklands (eg, an area with vs an area without a BBQ station) will provide ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ groups that mimic a controlled trial, a ‘quasi-experimental’ study design.10

It is possible that some people will have invested in a move to a neighbourhood near the Parklands based on knowledge that the enhancements would be made in the future. Multivariate adjustment for factors known to be associated with where a person can choose to live will be used to account for this selective migration. These factors include age, gender, country of birth, whether a person is in a couple (ie, married, civil partnership or cohabiting) or single, annual household income, employment status and highest educational qualification. In addition, the level of socioeconomic deprivation within a neighbourhood will be taken into account using the Australian Bureau of Statistics ‘Socio Economic Index For Areas’ scale of relative advantage and disadvantage.38 The distributions of these possible confounders are reported in table 4. Unlike the health outcomes and health-related behaviours at baseline, many of these potential confounders were differentially patterned according to proximity. People living nearer the Parklands tended to be younger, born in Australia, living in a couple and with higher annual household incomes. Neighbourhoods near the Parklands also tended to be less socioeconomically deprived. All Census Collection Districts covered in the sample are classified as ‘major city’ in the Accessibility-Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA).39

Table 4.

Patterning of possible confounders at baseline, by proximity to the Parklands

| Proximity to any part of the Western Sydney Parklands (km) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| N | 891 | 1525 | 1516 | 1596 | 1724 |

| Mean | Coefficient (95% CI) | ||||

| Age | 58.95 | 1.1 (0.2 to 1.9)* | 2.0 (1.1 to 2.8)*** | 3.2 (2.3 to 4.1)*** | 3.7 (2.8 to 4.6)*** |

| Per cent missing | 0 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Women | 54% | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.1) |

| Per cent missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Country of birth | 45% | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5)* | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5)** | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8)*** |

| Per cent missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not in a couple | 25% | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9)** | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5)* | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.6)*** |

| Per cent missing | 1.01 | 0.52 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.7 |

| Income <$20 k | 28% | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0)*** | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9)*** |

| Per cent missing | 25.36 | 27.48 | 26.12 | 27.38 | 25.58 |

| Unemployed or limiting long-term illness | 8% | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.6) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0)** | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| Per cent missing | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 1.5 | 1.39 |

| No educational qualifications | 20% | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9)** | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

| Per cent missing | 1.8 | 1.77 | 1.65 | 3.13 | 2.2 |

| Lowest SEIFA tertile | 21% | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7)*** | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8)*** | 3.0 (2.5 to 3.6)*** | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.4)*** |

| Per cent missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; from distance to Parklands <1 km.

SEIFA, Socio Economic Index For Areas (relative advantage/disadvantage scale).

Statistical analysis

Further use of GIS will be applied to refine and adapt measures of exposure and to define relevant ‘control’ groups according to the hypothesis being tested. The design is necessarily ‘intention to treat’ as information in the 45 and Up Study on whether people specifically visit the Parklands is not known. Multilevel models40 will be the primary mode of analysis used to quantify associations between changes in green space and changes in health outcomes and health-related behaviours. These types of models are ideally suited to longitudinal data analysis41 as they are able to take into account and explicitly model variance in outcome variables as people age, such as the estimation of ‘growth curves’.42 These models will be fit in purpose-developed statistical software such as MLwIN43 and estimated using relevant methods, such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC).44

Ethics and dissemination

All participants in the 45 and Up Study consented to the use of their questionnaire data and to data linkage. Ethical approval was obtained for the 45 and Up Study from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee. Findings will be disseminated through partner organisations (the Western Sydney Parklands and the National Heart Foundation of Australia), as well as to health and urban planning policymakers in parallel with scientific papers and conference presentations.

Conclusion

Using a large source of existing data and a quasi-experimental study design, the WSPLS will provide cost-effective and valuable insights on the health impact of a major investment in one of the largest urban green spaces in Australia. The findings from this natural experiment will provide information for future green space developments, health policymakers and land-use planners on ‘what works’ in communities with significant health need.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the generosity and support of the Western Sydney Parklands. They also thank the National Heart Foundation of Australia for their financial support. This research was completed using data collected through the 45 and Up Study (http://www.saxinstitute.org.au). The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner Cancer Council NSW; and partners: the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NSW Division); NSW Ministry of Health; beyondblue; Ageing, Disability and Home Care, Department of Family and Community Services; the Australian Red Cross Blood Service; and UnitingCare Ageing. They thank the many thousands of people participating in the 45 and Up Study. This study was funded by an early career research grant from Western Sydney University. TA-B's contribution was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (ID 100161).

Footnotes

Contributors: TA-B with support from XF and GSK conceived and designed the experiments. TA-B and XF performed the experiments and analysed the data. TA-B, XF and GSK wrote the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Heart Foundation of Australia (ID 100161).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hartig T, Mitchell R, de Vries S et al. Nature and Health. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:207–28. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartig T, Evans GW, Jamner LD et al. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J Environ Psychol 2003;23:109–23. 10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00109-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pretty J, Peacock J, Sellens M et al. The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise. Int J Environ Health Res 2005;15:319–37. 10.1080/09603120500155963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodicoat DH, O'Donovan G, Dalton AM et al. The association between neighbourhood greenspace and type 2 diabetes in a large cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006076 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Is neighborhood green space associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes? Evidence from 267,072 Australians. Diabetes Care 2014;37:197–201. 10.2337/dc13-1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson EA, Mitchell R, Hartig T et al. Green cities and health: a question of scale. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:160–5. 10.1136/jech.2011.137240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Government. Our cities our future: a national urban policy for a productive, sustainable and liveable future. Canberra: Department of Infrastructure and Transport, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles-Corti B, Badland H, Mavoa S et al. Reconnecting urban planning with health: a protocol for the development and validation of national liveability indicators associated with noncommunicable disease risk behaviours and health outcomes. Public Health Res Pract 2014;25:pii: e2511405 10.17061/phrp2511405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Astell-Burt T, Mitchell R, Hartig T. The association between green space and mental health varies across the lifecourse. A longitudinal study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:578–83. 10.1136/jech-2013-203767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell D et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: new Medical Research Council guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:1182–6. 10.1136/jech-2011-200375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS et al. Does rising crime lead to increasing distress? Longitudinal analysis of a natural experiment with dynamic objective neighbourhood measures. Soc Sci Med 2015;138:68–73. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyle PJ, Norman P, Popham F. Social mobility: evidence that it can widen health inequalities. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1835–42. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS et al. Understanding geographical inequities in diabetes: multilevel evidence from 114,755 adults in Sydney, Australia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;106:e68–73. 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astell-Burt T, Feng X. Investigating ‘place effects’ on mental health: implications for population-based studies in psychiatry. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2015;24:27–33. 10.1017/S204579601400050X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banks E, Redman S, Jorm L et al. , 45 and Up Study Collaborators. Cohort profile: the 45 and Up Study. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:941–7. 10.1093/ije/dym184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mealing NM, Banks E, Jorm LR et al. Investigation of relative risk estimates from studies of the same population with contrasting response rates and designs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:26 10.1186/1471-2288-10-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Greener neighborhoods, slimmer people? Evidence from 246,920 Australians. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38:156–9. 10.1038/ijo.2013.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Neighbourhood green space is associated with more frequent walking and moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in middle-to-older aged adults. Findings from 203,883 Australians in the 45 and Up Study. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:404–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Neighbourhood green space and the odds of having skin cancer: multilevel evidence of survey data from 267 072 Australians. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:370–4: (accepted 28 Nov 2013). 10.1136/jech-2013-203043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Mental health benefits of neighbourhood green space are stronger among physically active adults in middle-to-older age: evidence from 260,061 Australians. Prev Med 2013;57:601–6. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Does access to neighborhood green space promote a healthy duration of sleep? Novel findings from 259,319 Australians. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e003094 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Identification of the impact of crime on physical activity depends upon neighbourhood scale: multilevel evidence from 203,883 Australians. Health Place 2015;31:120–3. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng X, Astell-Burt T, Kolt GS. Do social interactions explain ethnic differences in psychological distress and the protective effect of local ethnic density? A cross-sectional study of 226 487 adults in Australia. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e002713 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Croteau K et al. Influence of neighbourhood ethnic density, diet and physical activity on ethnic differences in weight status: a study of 214,807 adults in Australia. Soc Sci Med 2013;93:70–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng X, Astell-Burt T. Neighborhood socioeconomic circumstances and the co-occurrence of unhealthy lifestyles: evidence from 206,457 Australians in the 45 and Up Study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e72643 10.1371/journal.pone.0072643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002;32:959–76. 10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byles JE, Gallienne L, Blyth FM et al. Relationship of age and gender to the prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in later life. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;1:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Information paper: use of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale in ABS Health Surveys, Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart AL, Kamberg CJ. Physical functioning measures. In: Stewart AL, ed. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham: Duke University Press, 1992:86–101. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syddall HE, Martin HJ, Harwood RH et al. The SF-36: a simple, effective measure of mobility-disability for epidemiological studies. J Nutr Health Aging 2009;13:57–62. 10.1007/s12603-009-0010-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 894 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng SP, Korda R, Clements M et al. Validity of self-reported height and weight and derived body mass index in middle-aged and elderly individuals in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2011;35:557–63. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The active Australia survey: a guide and manual for implementation, analysis and reporting. Canberra: AIHW, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown WJ, Trost SG, Bauman A et al. Test-retest reliability of four physical activity measures used in population surveys. J Sci Med Sport 2004;7:205–15. 10.1016/S1440-2440(04)80010-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Francis J, Giles-Corti B, Wood L et al. Creating sense of community: the role of public space. J Environ Psychol 2012;32:401–9. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenig HG, Westlund RE, George LK et al. Abbreviating the Duke Social Support Index for use in chronically ill elderly individuals. Psychosomatics 1993;34:61–9. 10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71928-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen T, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology 2010;21:383–8. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181d61eeb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pink B. Technical paper: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Australian Population and Migration Research Centre. ARIA (Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia). Secondary ARIA (Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia) 2012. http://www.adelaide.edu.au/apmrc/research/projects/category/about_aria.html

- 40.Leyland AH, Goldstein H. Multilevel modelling of health statistics. Chichester, UK: Wiley, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steele F. Multilevel models for longitudinal data. J R Stat Soc Ser A 2008;171:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tu YK, Tilling K, Sterne JA et al. A critical evaluation of statistical approaches to examining the role of growth trajectories in the developmental origins of health and disease. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1327–39: dyt157 10.1093/ije/dyt157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rasbash J, Browne W, Goldstein H et al. A user's guide to MLwiN. London: Institute of Education, 2000:286. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Browne WJ. MCMC estimation in MLwiN: version 2.0: Centre for Multilevel Modelling. University of Bristol, 2005. [Google Scholar]