Abstract

Objectives

Infantile nystagmus (IN) is a genetically heterogeneous condition characterised by involuntary rhythmic oscillations of the eyes accompanied by different degrees of vision impairment. Two genes have been identified as mainly causing IN: FRMD7 and GPR143. The aim of our study was to identify the genetic basis of both sporadic IN and X-linked IN.

Design

Prospective analysis.

Patients

Twenty Chinese patients, including 15 sporadic IN cases and 5 from X-linked IN families, were recruited and underwent molecular genetic analysis. We first performed PCR-based DNA sequencing of the entire coding region and the splice junctions of the FRMD7 and GPR143 genes in participants. Mutational analysis and co-segregation confirmation were then performed.

Setting

All clinical examinations and genetic experiments were performed in the Eye Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University.

Results

Two mutations in the FRMD7 gene, including one novel nonsense mutation (c.1090C>T, p.Q364X) and one reported missense mutation (c.781C>G, p.R261G), were identified in two of the five (40%) X-linked IN families. However, none of putative mutations were identified in FRMD7 or GPR143 in any of the sporadic cases.

Conclusions

The results suggest that mutations in FRMD7 appeared to be the major genetic cause of X-linked IN, but not of sporadic IN. Our findings provide further insights into FRMD7 mutations, which could be helpful for future genetic diagnosis and genetic counselling of Chinese patients with nystagmus.

Keywords: nystagmus, FRMD7 gene, novel mutations

Strengths and limitations of this study.

As very few studies have focused on sporadic cases, the aim of our study was to identify the genetic basis of sporadic infantile nystagmus (IN) and X-linked IN.

Two mutations in the FRMD7 gene, including one novel nonsense mutation, were identified in two X-linked IN families.

The results suggest that mutations in FRMD7 are the major genetic cause of X-linked IN, but not of sporadic IN.

Introduction

Infantile nystagmus (IN) is the most common oculomotor disorder and usually causes involuntary, rapid and repetitive movement of the eyes. Signs of IN usually appear at birth or develop within the first 6 months of life. The incidence of all forms of IN is estimated to be 14 per 10 000 individuals.1 The most common manifestation of IN is visual acuity impairment, which is caused by excessive motion of images on the retina or by the movement of images away from the fovea. The abnormal eye movement sometimes becomes worse when an affected person stares at an object or is feeling anxious. The cerebellum is thought to play a key role in ocular motor control.2 Eye oscillations can be horizontal, vertical, torsional, or a combination of all three, with horizontal being the most common. To date, the pathogenesis of IN remains unclear. Many researchers attribute the disease to abnormal control by the part of brain governing ocular motor systems.3 Currently, there is no effective treatment for IN, and only very limited surgical, optical or pharmaceutical therapies have been employed to improve nystagmus waveforms and visual acuity.4 5 With the exception of idiopathic IN, the condition can be complicated by other diseases such as albinism, achromatopsia, Leber congenital amaurosis and early visual loss. It presents as a component of other neurological syndromes and neurological diseases.6

IN displays extreme genetic and clinical heterogeneity, and the most common form of IN follows an X-linked pattern. To date, two major genes, FRMD7 and GPR143, have been identified as the causative genes of hereditary X-linked infantile nystagmus (XLIN).7 The FRMD7 gene contains an N-terminal FERM (F for 4.1 protein, E for ezrin, R for radixin and M for moesin) highly conserved domain and a FERM-adjacent domain without significant homology. Mutations in the FRMD7 gene are currently thought to be the most common cause of XLIN.8 Gene expression occurs mainly in the retina and in those parts of the brain that coordinate eye movement, like the cerebellum and the lateral ventricles.9 Although the exact function of this gene is still unclear, previous research showed that FRMD7 gene mutations may lead to nystagmus by disrupting the normal development of certain nerve cells in the brain and the retina. Most studies focused on the N-terminal FERM domain which may link the plasma membrane and the actin cytoskeleton. Previous studies also suggested a link between membrane extension during neuronal development and remodelling of the actin cytoskeleton. The other gene causing XLIN, GPR143, encodes a protein that binds to heterotrimeric G proteins and affects pigment production in the iris, retinal pigment epithelium and skin.10 This protein is thought to be involved in intracellular signal transduction. Mutations in GPR143 have also been shown to cause X-linked ocular albinism type 1 (OA1), which is a multi-symptom syndrome that can cause reduced visual acuity, nystagmus and strabismus.11 However, a deletion mutation of the GPR143 gene has also been reported in a Chinese IN family without the typical phenotype of ocular albinism.12 Nearly half of X-linked IN families have genetic defects in the FRMD7 gene. However, very few studies have investigated the genetic basis of sporadic cases of IN.13

In this study, we recruited a Chinese cohort of IN patients including 15 sporadic cases and 5 from families with X-linked IN. We performed molecular genetic analysis on the FRMD7 and GPR143 genes in these 20 unrelated patients to identify the causative mutations.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

This study received the approval of The Eye Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. Twenty Chinese families with idiopathic IN were recruited and peripheral blood samples were collected from some participants. We performed detailed ophthalmological examinations on selected patients and also examined visual acuities, intraocular pressure and angle of head turn and employed a slit lamp and fundoscopy.

DNA extraction

We extracted DNA from the 20 probands and some healthy members of each family using a DNA extraction kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was quantified using Nanodrop 2000 (Thermal Fisher Scientific, Delaware, USA).

Mutation screening and data analysis

The primers of all coding exons and exon-intron junctions of FRMD7 and GPR143 were designed according to previous studies.14 15 PCR and Sanger sequencing were utilised to amplify each exon of FRMD7 and GPR143 in each participant. Sequencing results were analysed by Mutation Surveyor (Softgenetics, Pennsylvania, USA) and the potential pathogenic effects of the mutations on protein function were estimated using MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org), Polyphen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) and SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/www/SIFT_enst_submit.html). Frequency was annotated according to the 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org/). Co-segregation of putative causative variants was performed in family members.

Results

Clinical observations

Twenty unrelated patients with IN were studied. The inheritance pattern in the five families was consistent with an X-linked mode of inheritance. The other 15 patients did not have family histories, indicating that they were all sporadic cases. All of the examined patients displayed symptoms of binocular involuntary horizontal eye movements with different intermediate frequencies. They also had reduced visual acuity, amblyopia and astigmatism. No other anomalies, for instance in the anterior eye segment, colour vision deficit or abnormalities in the optic nerves were found.

Mutation detection

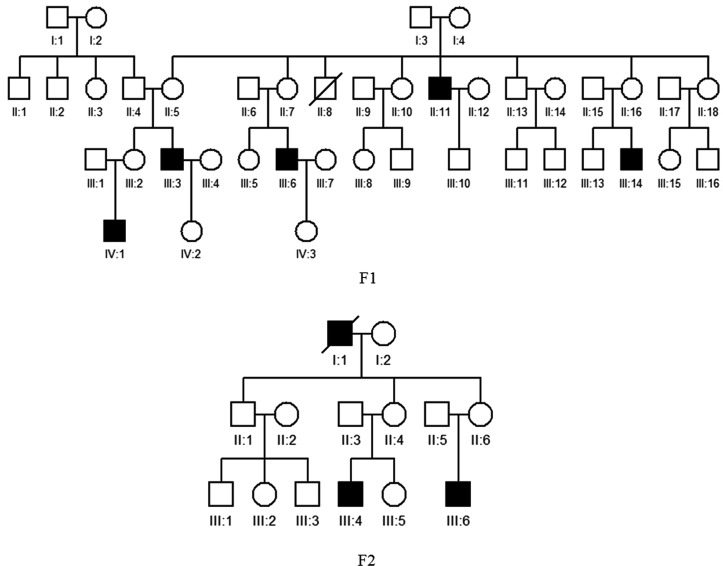

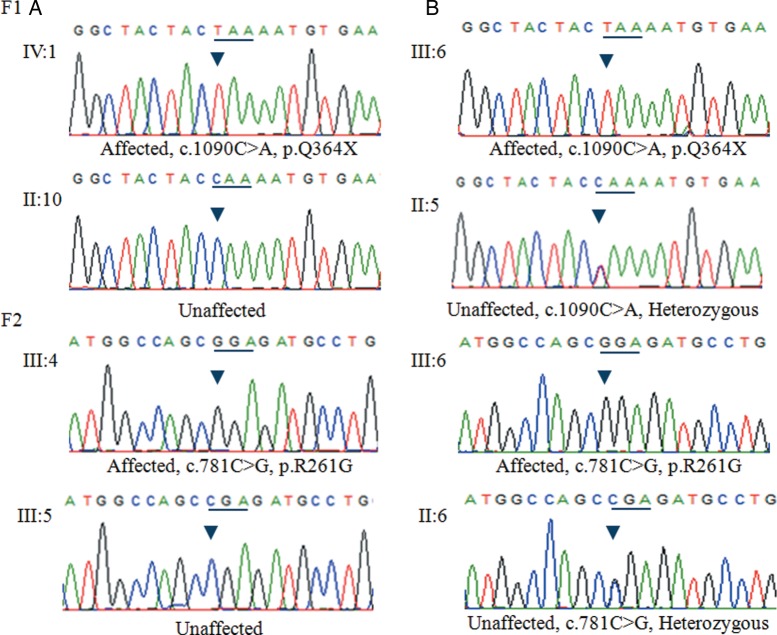

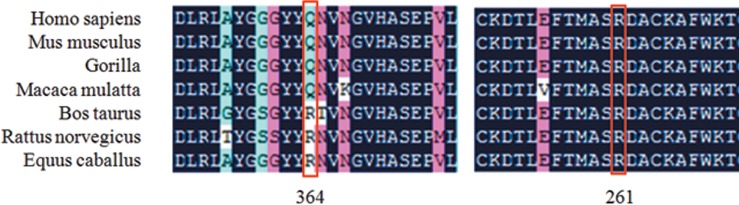

Sanger sequencing and mutational analysis revealed that five probands carried DNA variants in FRMD7 (table 1). However, three variants were considered to be polymorphisms because the frequency was >0.01 and the predicted functional effects displayed tolerance. Finally, two pathogenic mutations were identified among the five families with XLIN (table 1). A novel nonsense mutation, c.1090C>T (p.Q364X), in exon 12 of FRMD7, which would lead to a stop codon at position 364, was detected by Sanger sequencing analysis of a patient (IV:1) from family F1 (figure 1). Sequencing analysis of a patient (III:4) from family F2 (figure 1) showed that he harboured a missense mutation (c.781C>G, p.R261G) in exon 10 of FRMD7, which would result in amino acid substitution of arginine by glutamate at position 261 (figure 2). All protein prediction programmes determined this mutation was damaging and impacted on protein function. Notably, this mutation has previously been reported by other researchers.16 This mutation also followed an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern. The mutations Q364X and R261G were both located in highly conserved regions (figure 3). There are five affected males in family F1 and two affected males in family F2. The affected individuals were aged from 4 to 35 years and the age of onset was between 3 and 6 months of age (table 2). Of note, none of the participants showed abnormalities in the GPR143 gene. Consequently, we conclude that the two variants, c.1090C>T (p.Q364X) and c.781C>G (p.R261G) in the FRDM7 gene, are the disease-causing mutations in the two Chinese families with XLIN.

Table 1.

Summary of variants

| Family | Proband | Gene | Variant | Type | Frequency* | Predicted effects† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Male | FRMD7 | c.1090C>T (p.Q364X) | Hemizygous | None | Damaging |

| F2 | Male | FRMD7 | c.781C>G (p.R261G) | Hemizygous | None | Damaging |

| F6 | Female | FRMD7 | c.1403G>A (p.R468H) | Heterozygous | 0.07 | Tolerated |

| F7 | Female | FRMD7 | c.1403G>A (p.R468H) | Heterozygous | 0.07 | Tolerated |

| F20 | Female | FRMD7 | c.1533T>C (no change) | Heterozygous | 0.26 | Tolerated |

*Data from the 1000 Genomes Project.

†Predicted by SIFT.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of two recruited families with X-linked congenital nystagmus. Filled symbols indicate affected patients and unfilled symbols indicate unaffected subjects. Bars over the symbols indicate subjects enrolled in this study. Arrows indicate the probands.

Figure 2.

DNA sequence chromatograms of the unaffected and affected members in family F1 and F2. (A) A single transition mutation was observed at position 1090 (C>T) of the FRMD7 gene, causing substitution of Gln by a stop codon at codon 364 (Q364X). (B) A single transition mutation was observed at position 781(C>G) of the FRMD7 gene, causing substitution of Arg by Gly at codon 261 (A261G).

Figure 3.

Multiple-sequence alignment of the FRMD7 proteins from different species. The red box shows the location of the mutations. Mutations Q364X and R261G are both located in highly conserved regions.

Table 2.

Clinical features of families with X-linked infantile nystagmus

| Subject | Family | Age (years) | Sex | Onset age | BCVA (OD/OS) | Clinical findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV:1 | F1 | 2 | Male | 3 months | 0.3/0.3 | Horizontal nystagmus |

| III:3 | F1 | 27 | Male | 5 months | 0.2/0.3 | Horizontal nystagmus |

| II:5 | F1 | 45 | Female | – | 1.0/1.0 | Normal |

| II:10 | F1 | 38 | Female | – | 1.0/1.0 | Normal |

| III:4 | F2 | 12 | Male | 6 months | 0.3/0.2 | Horizontal nystagmus |

| III:5 | F2 | 7 | Female | – | 1.0/1.0 | Normal |

| III:6 | F2 | 4 | Male | 5 months | 0.2/0.2 | Horizontal nystagmus |

| II:6 | F2 | 31 | Female | – | 1.0/1.0 | Normal |

| II:5 | F3 | 36 | Male | 5 months | 0.1/0.1 | Horizontal nystagmus |

| III:5 | F4 | 8 | Male | 6 months | 0.3/0.3 | Horizontal nystagmus |

| III:3 | F5 | 37 | Male | 8 months | 0.2/0.2 | Horizontal nystagmus |

BCVA, best corrected visual acuity.

Discussion

The genetic aetiology of IN is not yet fully understood, especially as regards sporadic cases.17 In this study, we recruited 20 IN patients, including 15 sporadic cases and 5 from X-linked IN families. The major disease-causing genes, FRMD7 and GPR143, were screened.

More than 40 mutations have been found so far in the FRMD7 gene, and are mainly concentrated in two key regions: the FERM and FA domains.18 19 However, the function of the protein still remains poorly understood. Previous studies demonstrated the role of FRMD7 in the regulation of neuronal cytoskeletal dynamics at the growth cone through Rho GTPase signalling.20 21 Two mutations in the FRMD7 gene, one a novel nonsense mutation (c.1090C>T, p.Q364X) and one a reported missense mutation (c.781C>G, p.R261G), were identified in this study. In family F1, the affected males harboured the novel nonsense mutation (c.1090C>T, p.Q364X) and all exhibited typical manifestations of IN. The mutation (p.R261G) identified in family F2 was also recessive and has previously been reported in another Chinese X-linked IN family. We identified disease-causing mutations in two X-linked IN families, with a detection rate of 40% (2/5). The pedigrees of the other three X-linked IN families are shown in online supplementary figure S1. However, none of the putative mutations in FRMD7 or GPR143 were identified in any of the sporadic cases, suggesting that FRMD7 and GPR143 contribute very little to the aetiology in the sporadic IN patients.

bmjopen-2015-010649supp_figure.pdf (47.3KB, pdf)

We screened the FRMD7 and GPR143 genes in 15 sporadic patients with IN and in 5 probands with XLIN. Two disease-causing mutations were identified in the FRMD7 gene in two XLIN families, with a detection rate of 40%. However, no candidate variants were discovered in any of the sporadic patients with IN. The results demonstrated that the mutations in FRMD7 appeared to be the major genetic cause of hereditary X-linked nystagmus, but not of sporadic nystagmus. Our findings provide further insights into the mutation spectrum of FRMD7, which could be helpful for the future genetic diagnosis and genetic counselling of Chinese patients with nystagmus.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their family members for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: Z-BJ, HZ and X-PY conceived the idea, W-LD, X-LL, D-JX, H-YY, LY, S-ZX and JC collected the samples and performed the experiments, X-FH and FZ performed data analyses, and X-FH and Z-BJ wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR13H120001 to ZBJ, LQ14B020005 to XC), Zhejiang Provincial & Ministry of Health research fund for medical sciences (WKJ-ZJ-1417 to ZBJ), National Key Basic Research Program (2013CB967502 to ZBJ) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81371059 to ZBJ).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted with the approval of the Eye Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sarvananthan N, Surendran M, Roberts EO et al. The prevalence of nystagmus: the Leicestershire nystagmus survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50:5201–6. 10.1167/iovs.09-3486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel VR, Zee DS. The cerebellum in eye movement control: nystagmus, coordinate frames and disconjugacy. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:191–5. 10.1038/eye.2014.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Self J, Lotery A. The molecular genetics of congenital idiopathic nystagmus. Semin Ophthalmol 2006;21:87–90. 10.1080/08820530600614017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serra A, Dell'Osso LF, Jacobs JB et al. Combined gaze-angle and vergence variation in infantile nystagmus: two therapies that improve the high-visual-acuity field and methods to measure it. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:2451–60. 10.1167/iovs.05-1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taibbi G, Wang ZI, Dell'Osso LF. Infantile nystagmus syndrome: broadening the high-foveation-quality field with contact lenses. Clin Ophthalmol 2008;2:585–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trebušak Podkrajšek K, Stirn Kranjc B, Hovnik T et al. GPR143 gene mutation analysis in pediatric patients with albinism. Ophthalmic Genet 2012;33:167–70. 10.3109/13816810.2011.559651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabot A, Rozet JM, Gerber S et al. A gene for X-linked idiopathic congenital nystagmus (NYS1) maps to chromosome Xp11.4-p11.3. Am J Hum Genet 1999;64:1141–6. 10.1086/302324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarpey P, Thomas S, Sarvananthan N et al. Mutations in FRMD7, a newly identified member of the FERM family, cause X-linked idiopathic congenital nystagmus. Nat Genet 2006;38:1242–4. 10.1038/ng1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurtell MJ, Leigh RJ. Nystagmus and saccadic intrusions. Handb Clin Neurol 2011;102:333–78. 10.1016/B978-0-444-52903-9.00019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu JY, Ren X, Yang X et al. Identification of a novel GPR143 mutation in a large Chinese family with congenital nystagmus as the most prominent and consistent manifestation. J Hum Genet 2007;52:565–70. 10.1007/s10038-007-0152-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preising M, Op de Laak JP, Lorenz B. Deletion in the OA1 gene in a family with congenital X linked nystagmus. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:1098–103. 10.1136/bjo.85.9.1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou P, Wang Z, Zhang J et al. Identification of a novel GPR143 deletion in a Chinese family with X-linked congenital nystagmus. Mol Vis 2008;14:1015–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AlMoallem B, Bauwens M, Walraedt S et al. Novel FRMD7 mutations and genomic rearrangement expand the molecular pathogenesis of X-linked idiopathic infantile nystagmus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:1701–10. 10.1167/iovs.14-15938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Q, Xiao X, Li S et al. FRMD7 mutations in Chinese families with X-linked congenital motor nystagmus. Mol Vis 2007;13:1375–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang S, Guo X, Jia X et al. Novel GPR143 mutations and clinical characteristics in six Chinese families with X-linked ocular albinism. Mol Vis 2008;14:1974–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang B, Liu Z, Zhao G et al. Novel mutations of the FRMD7 gene in X-linked congenital motor nystagmus. Mol Vis 2007;13:1674–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abadi RV, Bjerre A. Motor and sensory characteristics of infantile nystagmus. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:1152–60. 10.1136/bjo.86.10.1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu J, Liang D, Xue J et al. A novel GPR143 splicing mutation in a Chinese family with X-linked congenital nystagmus. Mol Vis 2011;17:715–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watkins RJ, Thomas MG, Talbot CJ et al. The role of FRMD7 in idiopathic infantile nystagmus. J Ophthalmol 2012;2012:460956 10.1155/2012/460956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betts-Henderson J, Bartesaghi S, Crosier M et al. The nystagmus-associated FRMD7 gene regulates neuronal outgrowth and development. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:342–51. 10.1093/hmg/ddp500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolic M. The role of Rho GTPases and associated kinases in regulating neurite outgrowth. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2002;34:731–45. 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00167-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010649supp_figure.pdf (47.3KB, pdf)