Abstract

Objectives

Severe psychological stress is generally associated with an increased risk of acute cardiovascular diseases, such as myocardial infarction, but it remains unknown whether it also applies to atrial fibrillation. We conducted a population-based case–control study using nationwide Danish health registers to examine the risk of atrial fibrillation after the death of a partner.

Methods

From 1995 through 2014, we identified 88 612 cases with a hospital diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and 886 120 age-matched and sex-matched controls based on risk-set sampling. The conditional logistic regression model was used to calculate adjusted ORs of atrial fibrillation with 95% CIs.

Results

Partner bereavement was experienced by 17 478 cases and 168 940 controls and was associated with a transiently higher risk of atrial fibrillation; the risk was highest 8–14 days after the loss (1.90; 95% CI 1.34 to 2.69), after which it gradually declined. One year after the loss, the risk was almost the same as in the non-bereaved population. Overall, the OR of atrial fibrillation within 30 days after bereavement was 1.41 (95% CI 1.17 to 1.70), but it tended to be higher in persons below the age of 60 years (2.34; 95% CI 1.02 to 5.40) and in persons whose partner had a low predicted mortality 1 month before the death, that is, ≤5 points on the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (1.57; 95% CI 1.13 to 2.17).

Conclusions

The severely stressful life event of losing a partner was followed by a transiently increased risk of atrial fibrillation lasting for 1 year, especially for the least predicted losses.

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Previous studies have found that severely stressful life events increase the risk of cardiovascular events and case reports indicate emotional stress may be a triggering factor for arrhythmias. It remains unknown whether it also applies to risk of new onset of atrial fibrillation.

What does this study add?

This study found that the severely stressful life event of losing a partner was followed by an increased risk of atrial fibrillation lasting for 1 year. The risk was highest shortly after the loss and for the least predicted losses.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

These findings indicate that high levels of stress may increase the risk of developing new onset of atrial fibrillation. With a biologically plausible association early identification of this group should be encouraged and calls for further studies.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) represents the most common cardiac arrhythmia in the western world. The estimated life-time risk varies between 22% and 26%, and AF is one of the few heart diseases with increasing incidence.1 AF is associated with increased risk of death,2 stroke3 and heart failure,4 but also with a lower health-related quality of life.5 The treatment and the potentially related complications pose a major economic burden on the healthcare system.6

Mounting evidence indicates that severely stressful life events increase the risk of acute cardiovascular events like myocardial infarction,7 but no large studies have examined whether the association also applies to AF or atrial flutter. A few studies suggest that emotional stress may be a triggering factor for arrhythmia in persons with paroxysmal AF,8 and case reports indicate that this may also concern patients with no former history of AF.9 Furthermore, studies suggest that high-impact stress may cause pathophysiological changes that make the heart more vulnerable to arrhythmias by reduced parasympathetic modulation,10 which may cause excessive sympathetic activity11 and stimulate proinflammatory cytokines.12

The loss of a partner is considered one of the most severely stressful life events13 and is likely to affect most people, independently of coping mechanisms. Bereavement often causes mental illness symptoms such as depression, anxiety, guilt, anger and hopelessness.14

In a large population-based case–control study, we examined the association between partner bereavement and the risk of new onset of AF while taking into account the time since bereavement, comorbidity and medication use.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a population-based case–control study from 1995 through 2014, using prospectively collected information from four nationwide Danish registries on the Danish population of 5.6 million inhabitants. The Danish national healthcare system provides free access (tax-funded) to healthcare and partial reimbursement for prescribed medications. The unique Danish civil registration number (CRN), which is assigned to all Danish residents at birth or immigration, allowed us to link data at the personal level across all registries. The CRN has been used in the Danish Civil Registration System15 since 1968 and contains information on residence, cohabitant status, educational level, marital status, spouse, migration, vital status and date of death. The Danish National Patient Register16 was established in 1977 and holds information on discharge diagnoses from all Danish hospitals, and data from emergency rooms and outpatient clinics has also been recorded since 1995. Diagnoses are coded in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases; the eight revision (ICD-8) was used from 1971 to 1993, while the 10th revision (ICD-10) has been used since 1993.

Cases with AF

Persons with a first-time inpatient diagnosis of AF (from 1995 through 2014) were identified using information from the Danish National Patient Register (ICD-8: 427.93, 427.94 and ICD-10: I48; atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter). Information on the combined diagnosis of AF and atrial flutter has proven to have a high validity (positive predictive value: 92.6%; 95% CI 88.8% to 95.2%) in the Danish National Patient Register17 and has previously been used in epidemiological studies.18 We considered the date of the first admission diagnosis of AF between 1995 through 2014 to be the index date for included cases. The Danish National Patient Register was used to exclude people diagnosed with a heart-valve disease before the index date (ICD-8: 394–396 and ICD-10: I05, I06, I08, I34 and I35).

Control group

For each case, we randomly selected 10 controls (1:10) matched on age (±2 months) and sex. These controls were assigned an index date identical to that of the AF diagnosis for the corresponding cases. All controls were selected through risk-set sampling from the population of all persons alive and living in Denmark with no personal history of AF at the index date according to the Danish Civil Registration System.

Partner bereavement

We used the Danish Civil Registration System to identify cohabitant partner status, marital status, identification of corresponding spouse or partner, and all spousal/partner deaths for cases and controls prior to the index date. We used the Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index19 (ACCI) to classify the likelihood of death for all partners 1 month before his or her death, with allocated points for selected chronic diseases obtained from the Danish National Patient Register (1 point: myocardial infarct, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, connective tissue disease, ulcer, chronic liver disease and/or diabetes; 2 points: hemiplegia, moderate or severe kidney disease, diabetes with end organ damage, tumour, leukaemia and/or lymphoma; 3 points: moderate or severe liver disease; 6 points: malignant tumour, metastasis and/or AIDS) and for age (1 point: 50–59 years; 2 points: 60–69 years; 3 points: 70–79 years; 4 points: 80–89 years; 5 points: 90–99 years).

Covariates

Information on potential confounding factors was obtained from the Danish National Patient Register, the Danish National Diabetes Register,20 and the Danish National Prescription Register.21 Since 1990, the Danish National Diabetes Register has provided information on diabetes mellitus according to an algorithm developed on the basis of data from four nationwide Danish registers. Since 1995, complete computerised prescription records have been available in the Danish National Prescription Register; the database provides dispensing dates for all reimbursed drugs classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System.

From the Danish National Patient Register and the Danish National Diabetes Register, we obtained previous hospitalisation diagnoses on hypertension, ischaemic heart disease (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction and chronic ischaemic heart disease), cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism and diabetes mellitus, which may increase the risk of AF (see table 1). From the Danish National Prescription Register, we obtained information on used cardiovascular drugs classified according to ATC codes: vitamin K antagonists (MB01AA), ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II antagonists (MC09), β-blocking agents (MC07), lipid-modifying agents (MC10), calcium antagonists (MC08D), diuretics (MC03), nitrates (MC01DA), digoxin (MC01) and antiplatelet agents (MB01AC). Only prescriptions redeemed within 3 months before the index date were included. Maximum educational level was classified according to the United Nation's International Standard Classification of Education: low (<10 years), middle (10–15 years) and high (>15 years).22

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases with atrial fibrillation and controls from Denmark, 1995–2014

| Cases, number (%) | Controls, number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| (n=88 612) | (n=886 120) | |

| Partner bereavement | ||

| Yes | 17 478 (19.72) | 168 940 (19.07) |

| No | 71 134 (80.28) | 717 180 (80.93) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 41 764 (47.13) | 417 649 (47.13) |

| Male | 46 848 (52.87) | 468 480 (52.87) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–49 | 6678 (7.54) | 66 780 (7.54) |

| 50–59 | 11 299 (12.75) | 112 990 (12.75) |

| 60–69 | 20 875 (23.56) | 208 750 (23.56) |

| 70–79 | 25 808 (29.12) | 258 080 (29.12) |

| 80–100 | 23 952 (27.03) | 239 520 (27.03) |

| Civil status | ||

| Cohabitant* | 47 956 (54.12) | 472 338 (53.30) |

| Not cohabitant | 40 656 (45.88) | 413 782 (46.70) |

| Education (years) | ||

| <10 | 32 834 (37.05) | 313 635 (35.39) |

| 10–15 | 28 334 (31.98) | 280 719 (31.68) |

| >15 | 10 278 (11.60) | 103 633 (11.70) |

| Calendar time | ||

| 1995–2004 | 39 104 (44.13) | 391 040 (44.13) |

| 2004–2014 | 49 508 (55.87) | 495 080 (55.87) |

| Previous hospital diagnoses | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 29 895 (33.73) | 180 802 (20.40) |

| Hypertension | 17 406 (19.64) | 108 813 (12.28) |

| Ischaemic heart disease† | 16 680 (18.82) | 95 540 (10.78) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 909 (1.03) | 2115 (0.24) |

| Congestive heart failure | 6445 (7.27) | 26 414 (2,98) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1787 (2.02) | 11 527 (1.30) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 009 (12.42) | 87 646 (9.89) |

| Medicine‡ | ||

| ACE or A2R inhibitors | 21 514 (24.28) | 151 337 (17.08) |

| β-blockers | 19 176 (21.64) | 90 784 (10.25) |

| Digoxin | 8071 (9.11) | 16 350 (1.85) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 4583 (5.17) | 18 930 (2.14) |

| Diuretics | 28 414 (32.07) | 181 005 (20.43) |

| Nitrates | 6415 (7.24) | 29 455 (3.32) |

| Thrombocyte function inhibitors | 23 441 (26.45) | 158 623 (17.90) |

| Lipid modifying agents | 12 718 (14.35) | 102 710 (11.59) |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 7744 (8.74) | 7801 (0.88) |

*Married or living with a cohabitant partner.

†Angina pectoris, acute myocardial infarction, chronic ischaemic heart disease.

‡Redeemed prescriptions 3 months before index date.

A2R, adenosine receptor.

Statistical analysis

We calculated ORs and 95% CIs of AF using conditional logistic regression comparing the risk among bereaved against the cohabitant group. As we used risk-set sampling of controls, the ORs present unbiased estimates of the corresponding incidence rate ratios.23 In multiple conditional logistic regression models, we controlled for the covariates listed in table 1.

First, we calculated the ORs for AF according to the time since bereavement, and these were grouped according to time period: 0–7 days, 8–14 days, 15–30 days, 31–90 days, 91–365 days, 366–1095 days and >1095 days before the index date.

Second, we calculated the ORs of developing AF within 30 days after bereavement in subgroups of the population categorised according to sex, age, calendar time, cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus.

Third, we evaluated whether the effect of bereavement on AF depended on the health status of the partner 1 month before death. This was measured by the ACCI scores divided into three categories: lowest risk of death (0–5 points), intermediate risk (6–8 points) and highest risk (9–16 points). The division was made prior to the analysis to establish as much power in each category as possible.

Fourth, we examined the effect of being single on AF risk compared with cohabitating partners.

Finally, we performed a subanalysis after excluding cases and the corresponding controls who redeemed a prescription of an antithrombotic agent (ATC: MB01AA) before the index date.

Analyses were performed using STATA, V.13; StatCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA.

Results

More cases than controls had a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and/or hyperthyroidism and also received more medications for these conditions (table 1).

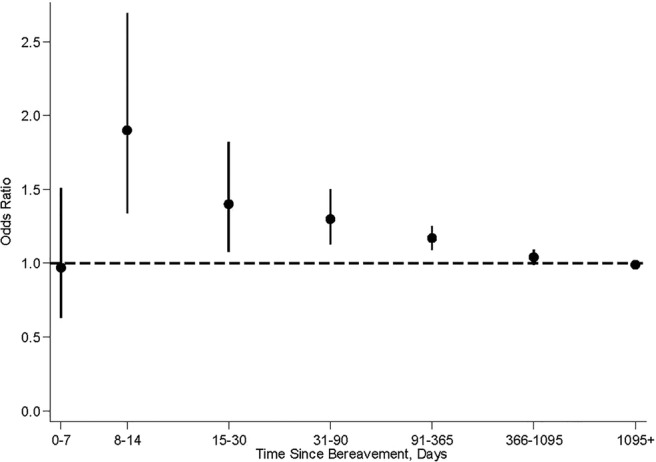

During the whole study period, partner bereavement was experienced by 17 478 (19.72%) cases and 168 940 (19.07%) controls; 144 cases and 1036 controls were bereaved within the past 30 days prior to AF. Bereavement was followed by a transiently higher risk of AF (figure 1). The OR was highest 8–14 days after the loss (1.90; 95% CI 1.34 to 2.69), after which it gradually declined. One year after the loss, it corresponded to a level close to that of the non-bereaved population (1.04; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.09).

Figure 1.

Adjusted ORs of AF according to time since bereavement versus non-bereaved in a population from Denmark between 1995 and 2014. * *ORs are adjusted for age, sex and hospital diagnosis for hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism, diabetes and cardiovascular medication (vitamin K antagonists MB01AA, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II antagonists MC09, β-blocking agents MC07, lipid-modifying agents MC10, calcium antagonists MC08D, diuretics MC03, nitrates MC01DA, digoxin MC01, antiplatelet agents MB01AC). †Point estimates are given with error bars representing 95% CIs. AF, atrial fibrillation.

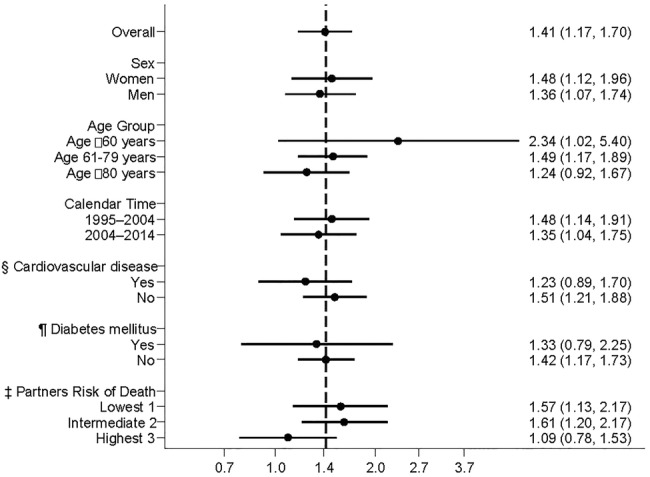

Overall, the OR of developing AF within 30 days after bereavement was 41% higher (1.41; 95% CI 1.17 to 1.70) in the bereaved population compared with the non-bereaved population (figure 2). This risk was relatively constant over subgroups characterised by sex, calendar time, pre-existing cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The highest OR was found among persons below the age of 60 years (2.34; 95% CI 1.02 to 5.40). The OR tended to increase with decreasing ACCI scores in the partner 1 month prior to the death; a high OR was found for those who lost a partner with low ACCI scores (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.13 to 2.17), whereas no risk increase was found for those who lost a partner with high ACCI scores (OR 1.09; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.53).

Figure 2.

Adjusted ORs of AF within 30 days after bereavement with specific characteristics versus non-bereaved with the same characteristics. * *The vertical dashed line represents the overall OR for AF within 30 days after bereavement compared with non-bereaved. The ORs (except for CVD and diabetes mellitus (DM)) are adjusted for age, sex and hospital diagnosis for hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, hyperthyroidism, diabetes and cardiovascular medication (vitamin K antagonists MB01AA, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II antagonists MC09, β-blocking agents MC07, lipid-modifying agents MC10, calcium antagonists MC08D, diuretics MC03, nitrates MC01DA, digoxin MC01, antiplatelet agents MB01AC). †Point estimates are given with error bars representing 95% CIs. §Cardiovascular disease: hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure. ¶DM: according to an algorithm developed on the basis of the Danish National Diabetes Register. ‡Risk of death in partner: corresponding ACCI scores 1 month before index day divided into three categories for statistical comparison. AF, atrial fibrillation; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

We found no difference in AF risk when we compared singles with cohabitating partners (OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.01), nor if we excluded cases and corresponding controls who had redeemed a prescription for an antithrombotic agent (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large population-based study, the severely stressful life event of losing a partner was associated with a transiently increased risk of AF, which lasted for about 1 year. The elevated risk was especially high for those who were young and those who lost a relatively healthy partner.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the risk of AF after stressful life events, but an association has been suggested by case reports.9 A few studies have examined the relationship between psychological distress and AF, but the association remains unclear. The Women's Health Study from the US24 followed 30 746 women for a median of 125 months and identified 771 patients with AF. The study used the Mental Health Inventory-5 to measure global psychological distress, but no association with AF was revealed. As the American study included only few severely distressed study participants and did not take timing into account, an acute effect of severe stress may have been overlooked. In our study, the association between bereavement and AF was weak 1 year after the bereavement if at all present. A cohort study from Australia25 followed 226 patients for a median of 6 days after cardiac surgery and identified 56 patients who developed AF. They used the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales to measure self-reported postoperative stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Their findings showed that only anxiety was associated with higher risk of AF. The Australian study was, however, limited by small sample size. In addition, the results may not apply to the general population as the study was based on a highly selected group of individuals who had just undergone cardiac surgery.

Our study indicated that one of the most severe types of stress is associated with an increased risk of AF. We used the ACCI scores of the deceased partner 1 month before the death as a proxy for the expectedness of the death because we presume that the stress associated with bereavement is more severe if the loss is unexpected.26 We found that the highest risk was associated with the least predicted losses, while no association was found for more expected losses (ie, the partners with the highest ACCI scores). A long-lasting disease with great suffering and considerable care may be stressful and place high demands on the partner, and death may sometimes even be a relief. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and male sex are well-known risk factors for AF.1 However, in our study, the OR of AF after bereavement did not differ much in the investigated subgroups during the 30-day period.

Bereavement is a major life event, which is known to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease,7 mental illness27 and death.28 The underlying causal mechanisms for the association between the loss of a partner and AF is unclear, but acute stress may possess direct arrhythmogenic properties by alternating autonomic control, influencing heart rate variability and enhancing proinflammatory cytokines.10–12 Animal studies have substantiated the importance of the neural component surrounding AF when manipulation of the autonomic pathways either promotes or eliminates AF.29 In addition, patients with paroxysmal AF often claim that emotional stress is a common triggering factor8 and increasing levels of perceived stress are associated with prevalent AF.30

The main strengths of our study include the population-based design and the large sample size, which allowed us to consider timing and study the association in high-risk populations. The case–control study was nested in a nationwide cohort and included all persons treated for inpatient incident AF in any Danish hospital during the study period. Denmark provides free access (tax-funded) to healthcare services for all residents, and the registration of AF is known to be valid (positive predictive value 92.6%).17 Controls were randomly selected from the underlying cohort using risk-set sampling. Thus, bias due to selection of study participants is an unlikely explanation for our findings. Since a precise day of onset is important in timing analysis, we only included persons with new onset of AF who were treated in hospitals as inpatients. We expect that the vast majority of these cases had an acute onset. Unfortunately, we do not have information on the diagnoses made in primary care in Denmark. However, the results were virtually unchanged when we excluded cases and corresponding controls who had redeemed a prescription of an antithrombotic agent before the index date. Information on the death of a partner was collected prospectively and did not rely on the memory of the study participants. Registration of death in the Danish Civil Registration System has a high validity and a completeness close to 100%, which implies that our assessment of death is accurate.15 In our study, the participants had to be married or cohabiting in order to be categorised as exposed to bereavement. This procedure is, however, unlikely to have introduced any bias as the results did not change much if we used only non-bereaved cohabitants as controls.

We adjusted for several confounding factors, such as medication and comorbid conditions, and found only little change in the estimates. However, residual confounding cannot be ruled out because we had no information on potential confounding factors such as lifestyle factors, physical activities and family history of AF. We believe that the risk of residual confounding is likely to be small as we cannot think of any possible confounder that could cause a transiently increased risk of AF shortly after bereavement. Adverse lifestyle factors (such as increased alcohol consumption, decreased sleep quality, poor diet and less physical activity)31 caused by the bereavement may be steps on the causal pathway from bereavement to AF1 and, therefore, should not be adjusted for.23

In conclusion, we found a transiently increased risk of AF after partner bereavement, especially if the loss was unpredicted according to the Charlson comorbidity index. Our results call for further studies aiming at evaluating whether the association also applies to more common, but less severe, stressors and at identifying causal mechanisms and treatment possibilities.

Footnotes

Contributors: SG, BC, MF-G and MV designed the study. SG, HSP, MF-G and MV acquired the data. SG, HSP, JC, MF-G, BC, JL and MV analysed and interpreted the data. SG drafted the report. All authors approved the final draft.

Funding: The study is supported by an unrestricted grant from the Lundbeck Foundation (grant number: R155-2012-11280).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D et al. . The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ Res 2014;114:1453–68. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB et al. . Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998;98:946–52. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.10.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marini C, De Santis F, Sacco S et al. . Contribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischemic stroke: results from a population-based study. Stroke 2005;36:1115–19. 10.1161/01.STR.0000166053.83476.4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D et al. . Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003;107:2920–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suman-Horduna I, Roy D, Frasure-Smith N et al. . Quality of life and functional capacity in patients with atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:455–60. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turakhia MP, Solomon MD, Jhaveri M et al. . Burden, timing, and relationship of cardiovascular hospitalization to mortality among Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 2013;166:573–80. 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey IM, Shah SM, DeWilde S et al. . Increased risk of acute cardiovascular events after partner bereavement: a matched cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:598–605. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson A, Madsen-Härdig B, Olsson SB. Arrhythmia-provoking factors and symptoms at the onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a study based on interviews with 100 patients seeking hospital assistance. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2004;4:13 10.1186/1471-2261-4-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziegelstein RC. Acute emotional stress and cardiac arrhythmias. JAMA 2007;298:324–9. 10.1001/jama.298.3.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckley T, Stannard A, Bartrop R et al. . Effect of early bereavement on heart rate and heart rate variability. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1378–83. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amar D, Zhang H, Miodownik S et al. . Competing autonomic mechanisms precedethe onset of postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1262–8. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00955-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation 1999;99:2192–217. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.16.2192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res 1967;11:213–18. 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet 2007;370:1960–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rix TA, Riahi S, Overvad K et al. . Validity of the diagnoses atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter in a Danish patient registry. Scand Cardiovasc J 2012;46:149–53. 10.3109/14017431.2012.673728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost L, Hune LJ, Vestergaard P. Overweight and obesity as risk factors for atrial fibrillation or flutter: the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study. Am J Med 2005;118:489–95. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J et al. . Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–51. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carstensen B, Kristensen JK, Marcussen MM et al. . The national diabetes register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):58–61. 10.1177/1403494811404278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):38–41. 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education. http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/international-standard-classification-of-education.aspx (accessed 23 Oct 2014).

- 23.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Timothy L. Modern epidemiology. 3rd edn Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whang W, Davidson KW, Conen D et al. . Global psychological distress and risk of atrial fibrillation among women: the Women's Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:e001107 10.1161/JAHA.112.001107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tully PJ, Bennetts JS, Baker RA et al. . Anxiety, depression, and stress as risk factors for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Heart Lung 2011;40:4–11. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keyes KM, Pratt C, Galea S et al. . The burden of loss: unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a national study. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:864–71. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Laursen TM, Precht DH et al. . Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1190–6. 10.1056/NEJMoa033160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christakis NA, Allison PD. Mortality after the hospitalization of a spouse. N Engl J Med 2006;354:719–30. 10.1056/NEJMsa050196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen MJ, Shinohara T, Park HW et al. . Continuous low-level vagus nerve stimulation reduces stellate ganglion nerve activity and paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmias in ambulatory canines. Circulation 2011;123:2204–12. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.018028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Neal WT, Qureshi W, Judd SE et al. . Perceived stress and atrial fibrillation: the REasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study. Ann Behav Med 2015;49:802–8. 10.1007/s12160-015-9715-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stahl ST, Schulz R. Changes in routine health behaviors following late-life bereavement: a systematic review. J Behav Med 2014;37:736–55. 10.1007/s10865-013-9524-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]