Abstract

Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation is a rare clinical entity with few case reports and limited series published in the literature. Bilateral shoulder dislocations are rare and of them, most are posterior. We present a highly unusual case of bilateral, atraumatic, anterior shoulder dislocation with concomitant comminuted greater tuberosity fracture on the right side, secondary to seizure, in a patient without known epilepsy, induced by oral chloroquine medication. We demonstrate the treatment approach that led to a satisfactory clinical outcome, evidenced by radiological union, clinical assessment and Patient Reported Outcome Measure data, following non-operative management of both shoulders. The unusual mechanism for anterior shoulder dislocation, the asymmetric dislocation pattern and peculiar precipitant for the causative seizure all provide interesting learning points from this case.

Background

The glenohumeral joint permits a wide range of movement at the expense of inherent bony stability. Accordingly, dislocations are a common presentation to the emergency department. Unilateral shoulder dislocations are predominantly anterior.1 Bilateral dislocations are rare and, of bilateral dislocations, most are posterior.2 Few cases of bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation have been published in the medical literature. Classical precipitants for bilateral shoulder dislocations include direct or indirect trauma and seizure secondary to electric shock, epilepsy or electroconvulsive therapy.3 Fracture dislocation injuries are not uncommon. Anterior shoulder dislocation is most commonly associated with fracture of the greater tuberosity. The classical mechanism for anterior shoulder dislocation is abduction, extension and external rotation. This position causes the greater tuberosity to abut the acromion, causing leverage of the humeral head out of the glenoid and can also account for greater tuberosity fracture.1

We present a highly unusual case of bilateral, atraumatic, asymmetrical anterior shoulder dislocation secondary to seizure in a patient without known epilepsy, induced by oral chloroquine medication.

Case presentation

A 30-year-old right-hand dominant man of eastern European descent presented to the emergency department following a second generalised tonic–clonic seizure in 24 h. One day prior, he had presented to a different hospital after a seizure. Following a CT of the head, which was reported as normal, he had been discharged with a plan for outpatient follow-up. He was brought to our hospital by ambulance after suffering a seizure while in bed. His partner witnessed a 2 min period of loss of consciousness, a brief tonic period followed by generalised shaking. On regaining consciousness, the patient reported of bilateral shoulder pain and was unable to mobilise from bed.

The patient was otherwise fit and well with no significant comorbidity. There was no history of epilepsy or seizure. He was a non-smoker and non-drinker. He admitted to taking chloroquine 500 mg twice daily for the past 4 days, prescribed in his home country of Slovakia, by a non-medical professional. The patient's wife had been diagnosed with a parasitic worm infection and he had been advised that he should complete a course prophylactically.

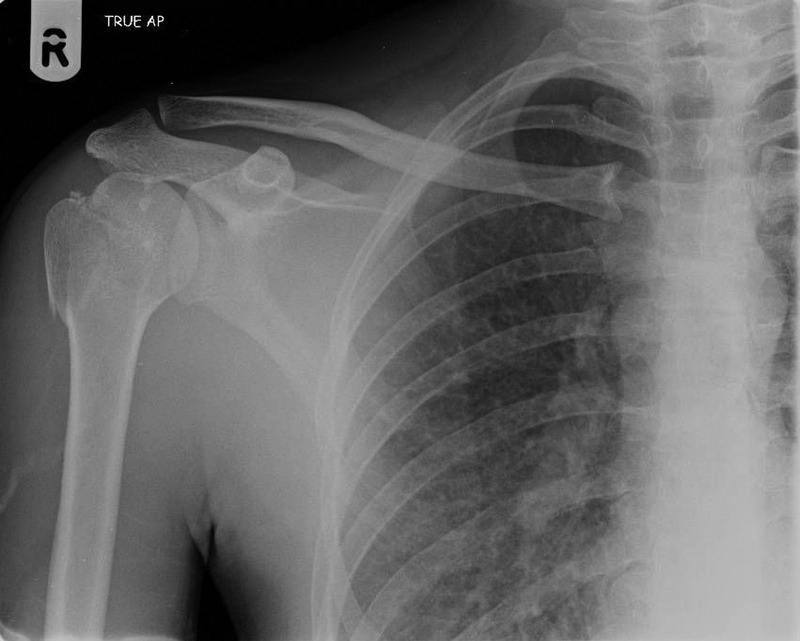

On presentation to the emergency department, clinical examination identified a post-ictal patient with no focal neurology. Bilateral swelling over the anterior aspect of the shoulders and squaring of the shoulders was noted. Attempted active and passive movements identified a globally restricted and painful range of motion. No distal neurovascular deficit was identified. Radiographic examination confirmed bilateral anterior shoulder dislocations with a right-sided comminuted greater tuberosity fracture. Figure 1 shows the right shoulder fracture dislocation seen at presentation.

Figure 1.

Right shoulder radiograph at presentation.

The patient underwent closed reduction of his dislocated shoulders under sedation, utilising the Kocher technique. Postreduction radiographs revealed successful reduction of both glenohumeral joints. While initial post-reduction radiographs revealed satisfactory joint reduction, the position of the right-sided greater tuberosity fracture remained displaced and in an unsatisfactory position, as demonstrated in figure 2. Following a trauma meeting discussion, the decision was made for abduction brace application and repeat radiographic examination in an attempt to improve the position of the greater tuberosity fragment to aid bony union. Repeat X-rays identified a satisfactory position and the decision was made for conservative management.

Figure 2.

Post-reduction radiograph demonstrating unsatisfactory position of greater tuberosity.

While an inpatient, under joint Medical and Orthopaedic care, an MRI of the brain was performed to exclude a structural cause for the patient's seizure. This identified no abnormality. The chloroquine was stopped on admission and was deemed to be the likely cause for his seizures following specialist neurology team review. No further neurological follow-up was arranged. The patient was discharged with his upper limbs immobilised in a polysling on the left side and an abduction brace on the right. He was followed up in the fracture clinic at 6 weeks, 6 months and 1 year postinjury. The patient was followed up at 6 months with radiological assessment, Oxford instability score (right side 43, left side 47) and constant score (right side 81, left side 93). Radiographic review at 6 months revealed the greater tuberosity to have demonstrated satisfactory bony union in an anatomical position, as shown in figure 3. Final follow-up at 12 months with Oxford instability score (right side 43, left side 47) and constant score (right side 87, left side 93), revealed marginal further functional improvement. At the final follow-up, the patient had returned to his preinjury level of physical activity, participating in weekly recreational football and rollerblading.

Figure 3.

Right shoulder radiograph at final follow-up demonstrating satisfactory bony union of greater tuberosity fracture.

Discussion

Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation is a rare clinical entity with few case reports and limited series published in the literature. In addition, most reported cases have occurred following trauma, with few reports of bilateral anterior dislocation occurring secondary to seizure activity.1 4 5 6 7 While the mechanism of bilateral posterior dislocation following seizure is well known, with powerful tonic contraction of the shoulder girdle musculature resulting in the stronger internal rotators causing adduction and internal rotation, the mechanism of bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation following seizure is less predictable. It has previously been suggested that bilateral anterior dislocations may occur as a result of the trauma associated with loss of consciousness during a seizure, rather than the seizure activity itself.1 8 Buhler et al reported in their series (26 shoulder dislocations post seizure, 13 anterior and 13 posterior), that recurrent shoulder instability following dislocation precipitated by seizure is much more common in anterior shoulder dislocations (12/13) rather than posterior (2/13). They also noted that recurrence rate following stabilisation is higher in post seizure anterior shoulder dislocations (40%) compared to posterior (12%).9

The principles of initial management of a bilateral shoulder dislocation are the same as for unilateral injury. Initial examination and documentation of neurovascular status is essential followed by early attempted closed reduction and immobilisation. Many reduction techniques have been described for anterior shoulder dislocation, with little agreement regarding the most safe and effective technique. In view of the lack of comparative studies of the safety and efficacy of reduction techniques, the chosen method often depends on physician preference. In this case, the Kocher technique was utilised. This involves the patient positioned supine or seated. The patient's forearm is flexed to 90° and the arm is adducted. With gentle in line traction, the arm is externally rotated to 70°, after which the physician forward flexes the arm until the characteristic ‘click’ of reduction is felt. The Kocher technique has a reported success rate of 81–100%.10 Following successful reduction, radiographic examination is required to confirm the reduction and assess for concomitant fracture. This patient had sustained a right-sided greater tuberosity fracture. This is a well-reported outcome following anterior shoulder dislocation, suggested to occur in approximately 10% of all shoulder dislocations.11 The greater tuberosity is the point of insertion of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles of the rotator cuff. Accordingly, a greater tuberosity fracture can have significant functional consequences and therefore must not be trivialised or overlooked. 12 Typically, non-operative treatment is advocated for greater tuberosity fractures with <5–10 mm displacement. Our patient was reviewed at 6 weeks, 6 months and 1 year following injury, clinically and radiologically and demonstrated anatomical bony union and unrestricted functional outcome with non-operative management in an abduction brace. He had returned to work, as a coffee vendor technician, within 6 weeks of injury and at 1 year he had returned to his preinjury level of physical activity. He reported no episodes of recurrent shoulder instability and was only occasionally troubled by mild pain from his left shoulder, particularly with overhead activities.

Interest in this case also lies in the unique aetiology of the seizure that resulted in bilateral dislocation. Chloroquine likely had an important role in the progression to tonic–clonic seizures in this patient. There was no family history of epilepsy, and no other identifiable causes for the seizures on history or examination. Seizures as a side effect of chloroquine use have been reported in various papers.13–16 Seizures have been linked to the use of high dose chloroquine at treatment levels for conditions such as malaria and leprosy and have also been due to chloroquine poisoning.17–19 The patient in this case had been erroneously prescribed chloroquine at high dose by a non-medical professional for the prophylactic treatment of gastrointestinal parasitic infection. Chloroquine is not recommended by the British national formulary as a treatment for parasitic infections. The only indication for using chloroquine is for malaria prophylaxis. This case serves to reinforce the importance of thorough history-taking including of drug and social history, in order to ensure that important aetiologies for the presentation are not overlooked.

Conclusion

Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocations are very rare and are most often posterior. We present an interesting orthopaedic presentation with a peculiar precipitant. The presence of the greater tuberosity fracture further adds complexity to this case and the subsequent non-operative management in an abduction brace with excellent functional outcome, at 6 months and 1 year, adds additional educational interest to this case.

Learning points.

The principles of initial management of bilateral shoulder dislocations are the same as for unilateral injuries, with thorough history-taking, examination, assessment and documentation of neurovascular status followed by attempted closed reduction.

Anterior shoulder dislocations can be complicated by a greater tuberosity fracture caused by abutment against the acromion as the glenohumeral joint dislocates.

In all orthopaedic injuries, careful history-taking must include a full medical and drug history to elucidate possible causes for the presentation.

Non-operative management is a viable treatment option for greater tuberosity fractures and utilisation of specialist braces—in this case an abduction brace—should be considered to help improve fracture alignment.

Thorough clinical, radiological and patient report outcome measure follow-up is important to assess treatment outcome and guide further management.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Siu YC, Lui TH. Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation. Arch Trauma Res 2014;3:e18178 10.5812/atr.18178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballesteros R, Benavente P, Bonsfills N et al. . Bilateral anterior dislocation of the shoulder: review of seventy cases and proposal of a new etiological-mechanical classification. J Emerg Med 2013;44:269–79. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.07.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunlop CC. Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation—a case report and review of literature. Acta Orthop Belg 2002;68:168–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turhan E, Demirel M. Bilateral anterior glenohumeral dislocation in a horse rider: a case report and a review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008;128:79–82. 10.1007/s00402-007-0347-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lasanianos N, Mouzopoulos G. An undiagnosed bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation after a seizure: a case report. Cases J 2008;1:342 10.1186/1757-1626-1-342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meena S, Saini P, Singh V et al. . Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2013;4:499–501. 10.4103/0976-9668.117003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozcelik A, Dincer M, Cetinkanat H. Recurrent bilateral dislocation of the shoulders due to nocturnal hypoglycemia: a case report. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2006;71:353–5. 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellazzini MA, Deming DA. Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation in a young and healthy man without obvious cause. Am J Emerg Med 2007;25:734.e1–3.. 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buhler M, Gerber C. Shoulder instability related to epileptic seizures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002;11:339–44. 10.1067/mse.2002.124524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youm T, Takemoto R, Park BK. Acute management of shoulder dislocations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014;22:761–71. 10.5435/JAAOS-22-12-761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manoharan G, Singh R, Ahmed B et al. . Acute spontaneous atraumatic bilateral anterior dislocation of the shoulder joint with Hill-Sachs lesions: first reported case and review of literature. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:pii: bcr2013202847 10.1136/bcr-2013-202847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBottis D, Anavian J, Green A. Surgical management of isolated greater tuberosity fractures of the proximal humerus. Orthop Clin North Am 2014;45:207–18. 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penélope A, Phillips-Howard PA, ter Kuile FO. CNS adverse events associated with antimalarial agents. Drug Saf 1995;12:370–83. 10.2165/00002018-199512060-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen E, Ronne T, Ronn A et al. . Reported side effects of chloroquine, chloroquine plus proguanil, and mefloquine as chemoprophylaxis against malaria in Danish travelers. J Travel Med 2000;7:79–84. 10.2310/7060.2000.00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corominas N, Gascon J, Mejias T et al. . Adverse effects associated with antimalarial chemoprophylaxis. Med Clin (Barc) 1997;108:772–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamolekun B. Seizures associated with chloroquine therapy. Cent Afr J Med 1992;38:350–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiemann R, Coulaud JP, Bouchaud O. Seizures after antimalarial medication in previously healthy persons. J Travel Med 2000;7:155–6. 10.2310/7060.2000.00048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebenso BE. Seizure following chloroquine treatment of type II lepra reaction: a case report. Lepr Rev 1998;69:178–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy VG, Sinna S. Chloroquine poisoning: report of two cases. Acta Aneaesthesiol Scand 2000;44:1017–20. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440821.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]