Abstract

Eating disorders in the form of anorexia and bulimia are becoming increasingly common in young adults and children. Most of the patients are initially seen by their general practitioner (GP) and it may take several months before the facts are pieced together and an underlying eating disorder is identified. However, other medical conditions, albeit rare, should be considered when assessing these young adults as potentially missing them can lead to devastating consequences. This case highlights how a 15-year-old girl who presented to her GP with a history suggestive of an eating disorder and had a body mass index below the 0.4th centile, in fact had classical symptoms and clinical signs of primary adrenal failure, or Addison's disease.

Background

Adolescent girls presenting with features of low weight, variable appetite, fatigue and unusual eating habits are common reasons for a parent to take their child to see their general practitioner (GP). It is not uncommon for a number of these children to subsequently be referred for a paediatric outpatient review.

On reviewing such patients, particularly adolescent girls, the possibility of an underlying eating disorder is often considered. Nicholls et al1 have recently highlighted that, although the overall incidence of eating disorders has remained static over the past several decades, individuals with anorexia nervosa are presenting at much early ages.

Anorexia nervosa and primary Addison's disease can both present with similar clinical features (table 1), however, there are some marked differences that can assist in identifying this subgroup of patients who have this potentially fatal condition.

Table 1.

Key similarities and differences between anorexia nervosa and primary Addison's disease

| Anorexia nervosa | Primary Addison's disease |

|---|---|

| Low body weight | Low body weight |

| Low BMI | Low BMI |

| Distorted perception of body image | Normal perception of body image |

| Fatigue | Fatigue and weakness |

| Restriction of energy intake | No restriction of energy intake; salt craving |

| Induced vomiting | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea |

| Malnutrition | Dehydration |

| Hypotension and bradycardia | Hypotension and normal or increased heart rate |

| Hypothermia | Normothermic |

| Ammenorhoea | Ammenorhoea less frequent (25%) |

| Decreased: GnRH, LH, FSH, IGF-1, testosterone, T3, T4, ADH | Electrolyte abnormalities: hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia |

| Increased: GH, cortisol | Decreased: cortisol elevated: ACTH |

| Hypoglycaemia | Hypoglycaemia |

| Hyperpigmentation, xerosis | Hyperpigmentation of skin, mucosa, palmar creases, axillae, gingival borders |

| Lanugo body hair and hirsutism | Decreased pubic and axillary hair development in pubertal patients |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADH, antidiuretic hormone; BMI, body mass index; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GH, growth hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; LH, luteinising hormone; T4, thyroxine; T3, triiodothyronine.

Case presentation

We present a case of a 15-year-old Caucasian girl who was referred by her GP to a general paediatric outpatient clinic, with a 6-month history of fatigue, and prolonged recovery from viral illnesses with intermittent vomiting and low weight.

Since her GP's initial review for a gastroenteritis illness, she had been reviewed a further four times. On all of these occasions, her GP had documented symptoms of ongoing fatigue, vomiting, very low appetite in addition to breathlessness, for which he started her on a steroid inhaler. Furthermore, on all of these consultations she was noted to have low weight and a low body mass index (BMI). At the paediatric consultation, her family described how she had developed extreme salt craving behaviour in the form of eating olives and drinking pints of gravy over the preceding months. She was one of three children, with no significant medical history prior to the onset of these symptoms. There was no significant family history apart from her maternal grandmother who had a history of rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis.

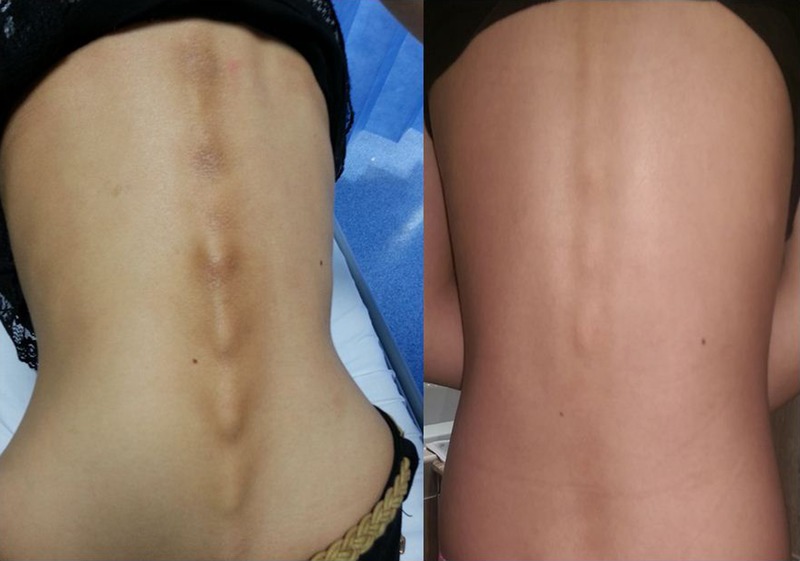

On examination, the patient appeared noticeably tanned compared to her older sister and mother, with evidence of hyperpigmentation in her skin creases and skin overlying the spinous processes and nipples (figures 1–3). Her blood pressure (BP) was 88/30 mm Hg, heart rate 96/min, weight 28.25 kg (<0.4th centile), height 149 cm (0.4th—2nd centile) and BMI 12.7 kg/m2 (significantly below the 0.4th centile). She still had regular periods.

Figure 1.

Hyperpigmentation of thoracic and lumbar spine at presentation (left) and initiation of treatment (right). Also, note low body mass index at presentation.

Figure 2.

The patient before diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Figure 3.

The patient after diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Blood tests performed by her GP several months earlier had identified hyponatraemia, with a sodium level of 129 mEq/L. Repeat electrolytes in clinic identified a sodium level of 133 mEq/L (low), potassium level of 4.2 mEq/L (normal) and glucose of 5.0 (normal). A short Synacthen test was performed that day and was grossly abnormal, demonstrating a flat response, the results of which are shown in table 2. These results were consistent with a diagnosis of Addison's disease.

Table 2.

The investigations that the patient had, which are consistent with a diagnosis of primary autoimmune Addison's disease

| Investigation | Result | Units | Normal values |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTH | 4850 | ng/L | <60 |

| Cortisol-SNT baseline | 112 | nmol/L | |

| Cortisol-SNT 30 min | 95 | nmol/L | |

| Cortisol-SNT 60 min | 92 | nmol/L | |

| Aldosterone | <89 | pmol/L | 140–830 |

| Plasma renin | 15.0 | nmol/L/h | 0.8–3.0 |

| Adrenal antibodies | Positive | ||

| Thyroid peroxidase antibodies | <33 | IU/mL | 60–100 |

| Anti GAD 2 antibodies | Negative | ||

| TSH | 4.0 | mU/L | 0.27–4.20 |

| Sodium | 133 | mmol/L | 132–145 |

| Potassium | 4.2 | mmol/L | 3.1–5.1 |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; GAD, glutamic acid decarboxylase; SNT, stimulation test; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Differential diagnosis

- Psychiatric

- 1. Anorexia nervosa

- Endocrine

- 1. Addison's disease

- 2. Diabetes mellitus

- 3. Hyperthyroidism

- Infective

- 1. Chronic infection; tuberculosis, HIV

- Inflammatory/autoimmune

- 1. Inflammatory bowel disease

- 2. Coeliac' disease

- Other

- 1. Malignancy—primary or secondary

Treatment

Steroid treatment was initiated in the form of hydrocortisone 10 mg in the morning and at lunchtime and 5 mg in the evening (total dose 20 mg/m2). Fludrocortisone at 100 μg was started once a day after 24 h of hydrocortisone. Education was provided regarding emergency treatment regimes in the event of any future illnesses and an emergency pack, which included intramuscular hydrocortisone, was given.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was followed up in the tertiary paediatric endocrinology clinic 2 months later, where she was found to have responded well to the replacement steroid therapy and her fludrocortisone dose was increased to 150 μg. Her weight had increased to 38 kg and her BMI had increased to 17.3 kg/m2. Her pigmentation identified at presentation had significantly improved (figures 1–3).

Discussion

This case highlights the importance of considering other diagnoses when faced with relatively common symptoms particularly in the adolescent teenage girl where it is recognised that the prevalence of eating disorders is high.1 In this case, a teenage girl presenting with low weight and BMI in combination with fatigue on further questioning had classical features of Addison's disease including salt craving behaviour and hyperpigmentation. She also, importantly, had features of tachycardia and was having normal periods, making a diagnosis of anorexia less likely.

Similar to our case, Tobin et al2 published a case of a 20-year-old man who presented with anorexia, vomiting and significant weight loss. He was initially diagnosed as having anorexia nervosa but, after presenting 1 month later with severe dehydration and hyponatraemia, was subsequently identified to have Addison's disease. After initiating steroid treatment he proceeded to eat normally and gained weight.

The International Classification of Diseases 103 criteria outline the features for diagnosing anorexia nervosa. These include weight loss or in the case of children a lack of weight gain, ‘leading to a body weight of at least 15% below the normal or expected weight for age and height’ (p.135). This is in addition to food avoidance behaviour with an abnormal self-perception of body image. Adolescent girls can also experience other endocrine disturbances such as amenorrhoea.

Primary adrenal failure occurs typically secondary to an autoimmune destructive atrophy of the adrenal glands, leading to Addison's disease.4 Clinical symptoms include weight loss, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, fatigue and salt craving behaviour. Symptoms are of gradual onset as the process of partial to complete adrenal insufficiency occurs, which can take months to years and can make recognition and subsequent diagnosis challenging. Clinical signs include hyperpigmentation secondary to raised adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels and reduced pubic and axillary hair, in addition to hypotension.4

Patients with Addison's disease are at risk of adrenal crises at times of acute stress or illness, due to the impaired natural cortisol response. Subsequently, treatment in the form of hydrocortisone and mineralocorticoid therapy, are started with immediate effect on diagnosis. Glucocorticoid therapy is given in 2–3 divided doses per day with two-thirds given in the morning to mirror the natural diurnal variation in cortisol secretion. Emergency packs are given to children and young adults with Addison's disease with instructions on how to increase their maintenance glucocorticoid dose during times of illness or acute stress to prevent adrenal crises.4

It is because of these adrenal crises that Addison's disease stands as an endocrine disorder that should not be missed. Undiagnosed children can present in crisis with hypotension, hypoglycaemia and dehydration, which if untreated and unrecognised can lead to shock, a comatosed state and death. Subsequently, an adrenal crisis accounts for a medical emergency.

Learning points.

Although eating disorders are becoming increasingly common in adolescent girls, the differential diagnosis of Addison's disease should always be considered.

It is vital that children presenting with low body mass index, variable appetite, fatigue and vomiting, have a careful history and examination to assess for atypical signs associated with endocrine pathologies such as Addison's disease.

Addison's disease is a potentially fatal condition and subsequently requires immediate steroid treatment.

Patients and their families should, on diagnosis, be educated on how to manage the Addison's disease during times of acute stress or illness to prevent potentially deadly adrenal crises.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the role and contribution of Dr Tony Hulse, Consultant Paediatric Endocrinologist and Ms Sara Pigott, Paediatric Endocrinology Specialist Nurse, for their involvement in the case.

Footnotes

Contributors: KN and NB contributed to the design and revision of this case report. NP is the guarantor and approved the final version.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nicholls DE, Lynn R, Viner RM. Childhood eating disorders: British national surveillance study. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198:295–301. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobin MV, Morris AI. Addison's disease presenting as anorexia nervosa in a young man. Postgrad Med J 1988;64:953–5. 10.1136/pgmj.64.758.953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders—diagnostic criteria for research. Vancouver, 1993. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/GRNBOOK.pdf (accessed 25 Feb 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neary N, Nieman L. Adrenal insufficiency: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2010;17:217–23. 10.1097/MED.0b013e328338f608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]