Abstract

We investigated the role of histone methyltransferase Ezh2 in tangential migration of mouse precerebellar pontine nuclei, the main relay between neocortex and cerebellum. By counteracting the sonic hedgehog pathway, Ezh2 represses Netrin1 in dorsal hindbrain allowing normal pontine neuron migration. In Ezh2 mutants, ectopic Netrin1 derepression results in abnormal migration and supernumerary nuclei integrating brain circuitry. Moreover, intrinsic topographic organization of pontine nuclei according to rostrocaudal progenitor origin is maintained throughout migration and correlates with patterned cortical input. Ezh2 maintains spatially-restricted Hox expression which in turn regulates differential expression of the repulsive receptor Unc5b in migrating neurons, generating subsets with distinct responsiveness to environmental Netrin1. Thus, Ezh2-dependent epigenetic regulation of intrinsic and extrinsic transcriptional programs controls topographic neuronal guidance and connectivity in the cortico-ponto-cerebellar pathway.

In mammals, cortical motor and sensory information is mostly relayed to the cerebellum via the hindbrain precerebellar pontine nuclei (PN), which include pontine gray and reticulotegmental nuclei. The developing hindbrain is rostrocaudally segregated into progenitor compartments, or rhombomeres (r1–r8) (1), genetically defined by nested Hox gene expression (2). Mouse PN neurons are generated from r6–r8 lower rhombic lip progenitors (3), undergo a long-distance caudorostral tangential migration via the anterior extramural stream (AES), and settle beside the ventral midline (Fig. 1, A and B) (4, 5). Intrinsic expression of transcription factors and guidance receptors and extrinsic distribution of ligands are important for AES migration (6–8). However, little is known about the epigenetic regulation of these transcriptional programs. Here, we addressed the role of Ezh2, which is member of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 and trimethylates histone H3 at Lysine 27 (H3K27me3) (9).

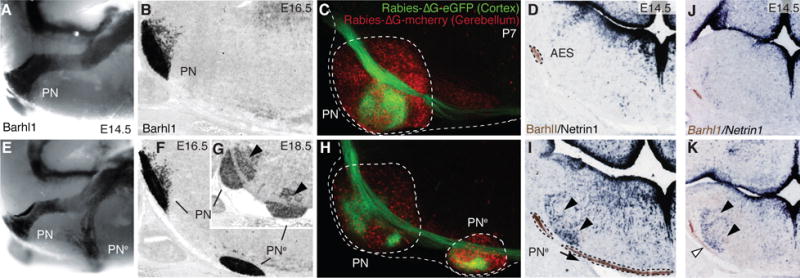

Fig. 1. Ezh2 non-cell autonomous role in pontine neuron tangential migration.

(A, B, E, F and G) Migratory phenotypes in control (A,B) and r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (E–G). Barhl1 in situ hybridization in E14.5 whole-mount (A,E), and E16.5 (B,F), E18.5 (G) sagittal sections. Pontine gray and reticulotegmental (arrowheads, G) nuclei (PN) are duplicated (PNe). (C and H) Tracings from P7 cortex (Rabies-ΔG-eGFP) and cerebellum (Rabies-ΔG-mCherry) in controls (C) and r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (H). Pontine (PN) and ectopic (PNe) nuclei are connected to cortex and cerebellum. (D, I, J and K) Barlh1/Netrin1 expression in E14.5 control (D), r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl (I), r5post::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl;Shhfl/+ (K), r5post::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl;Shhfl/fl (J) coronal sections. Ectopic Ntn1 (arrowheads,I,K) and PNe ectopic migration (arrows,I,K) are partially rescued (J).

Ezh2 transcripts are maintained through late stages in lower rhombic lip progenitors, migratory stream and PN neurons (fig. S1), while H3K27m3 is detected throughout the hindbrain (fig. S2). To conditionally inactivate Ezh2, we generated transgenic lines in which Cre is driven by rhombomere-specific enhancers in spatially-restricted regions tiling the caudal hindbrain ((10), figs. S3 and S4). To assess cell-autonomous and/or region-specific non-cell-autonomous Ezh2 function in pontine neuron migration, we first crossed Krox20::Cre (10) to an Ezh2fl/fl allele (10) (Krox20::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl). Inactivation in r3 and r5, which do not contribute to the pontine migratory stream (3), resulted in small ectopic pontine nuclei in posterior r5 (PNe, fig. S5), supporting an Ezh2 non-cell-autonomous role. Deletion in r5 and r6 (r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl) resulted in a more prominent phenotype. A neuronal subset split from the migratory stream, turned ventrally, and generated an ectopic duplication of PN (PNe) (Fig. 1, E to G). PNe neurons were non-recombined Ezh2+/+ H3K27me3+ located within the r5–r6-derived territory mostly devoid of H3K27me3 (fig. S2), further confirming Ezh2 non-cell-autonomous function.

To assess whether ectopic PNe integrated cortico-cerebellar connectivity, we carried out cortex-to-PN and cerebellum-to-PN tracings. We injected viral constructs expressing GFP (Rabies-ΔG-GFP) and/or mCherry (Rabies-ΔG-mCherry) in P2 wild type, r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl, and Krox20::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants. At P7, PN and PNe triggered collateralization of corticospinal axons and innervated the cerebellum (Fig. 1, C and H, fig. S6).

To evaluate Ezh2 cell-autonomous function, we used the Wnt1::Cre deleter (10). Ezh2 transcripts and H3K27me3 were selectively deleted from lower rhombic lip and migratory stream in Wnt1::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (fig. S2 and S7). Nonetheless, the mutation was not sufficient to induce ectopic posterior pontine neuron migration (Fig. 2, J and M, figs. S5 and S7). The most severe phenotype was observed in Hoxa2::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants, where Ezh2 was inactivated in both AES neurons and their migratory environment, i.e. throughout r3–r6 and dorsal r7–8 derived structures including the lower rhombic lip (figs. S2 and S3). The whole AES did not migrate anterior to r6 and settled into a single posterior ectopic nucleus (PNe, fig. S5). Thus, Ezh2 has a non-cell-autonomous role in AES migration, which is enhanced by a cell-autonomous function in progenitors and migrating neurons.

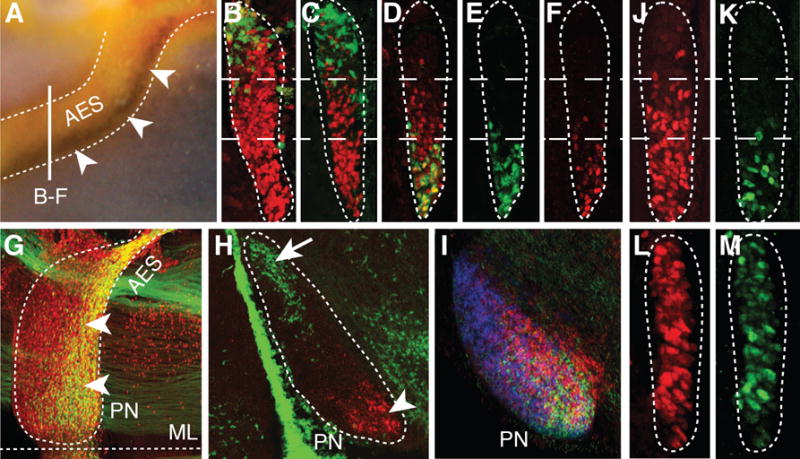

Fig. 2. Intrinsic topography of pontine migratory stream and nuclei and Ezh2 dependent Hox regulation.

(A) Hoxb5/Barhl1 in situ hybridization on E15.5 whole-mount brain (lateral view). Arrowheads show Hoxb5+ neuron ventral restriction in anterior extramural stream (AES). (B to C) E15.5 r5–6::Cre;R26RZsGreen AES coronal sections co-stained with ZsGreen/Pax6 (red) (B) or ZsGreen/Hoxb4 (red) (C) showing complementary dorsal ZsGreen+/ventral Hoxb4+ cell distributions (bar in (A) shows section level). (D to F) E15.5 Hoxa5::Cre;R26RZsGreen AES sections showing partially overlapping ZsGreen/Hoxb4 (red) co-stainings with offset dorsal limits (D), while ZsGreen+ (E) and Hoxa5+ (F) neurons display similar ventral restriction. (G to H) E15.5 whole-mount Hoxa5::Cre;R26RZsGreen (G) or r5–6::Cre;R26RZsGreen (H) sagittal sections co-stained with ZsGreen/Pax6 (red) or ZsGreen/Hoxa5 (red), respectively, illustrating posterior pontine nuclei (PN) restriction of Hoxa5+ neurons (arrowheads, G,H), and anterior restriction of r6-derived neurons (arrow, H). (I) Hoxb3/Hoxb4/Hoxb5 nested in situ expression patterns on PN sagittal section (J to M) Hoxb4 (red) and Hoxa5 (green) immunostainings of E15.5 Wnt1::Cre;Ezh2fl/+ control (J,K) and Wnt1::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutant (L,M) AES. In (L,M), Hoxb4 and Hoxa5 loose their spatial restriction and are ectopically derepressed up to the dorsal edge of the AES. ML, ventral midline.

Netrin1 (Ntn1) and Slit1-3 are attractive/repulsive secreted cues that influence pontine neuron migration (6, 7). While Slit1-3 expression was not altered in E14.5 r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (fig. S8), Ntn1, normally expressed in floor-plate and ventral ventricular progenitors (Fig. 1D, fig. S5) (11), was ectopically expressed in dorsal progenitors and mantle layer medially to the AES in r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl, Krox20::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl, Hoxa2::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl and r5post::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (Fig. 1I, fig. S5). Additional deletion of Shh was sufficient to prevent strong ectopic Ntn1 activation in dorsal progenitors of E12.5 r5post::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl;Shhfl/fl conditional mutants (fig. S5). At E14.5, ectopic Ntn1 was almost undetectable partially rescuing the Ezh2 knockout (Fig. 1, J and K, fig. S5). Therefore, Ezh2 is required to restrict Ntn1 expression to ventral progenitors by silencing Ntn1 in dorsal neural tube. However, Ezh2 deletion is not sufficient to ectopically induce Ntn1, which additionally requires Shh signaling from the floor plate. Thus, in the dorsal neural tube, Ezh2-mediated epigenetic repression of Ntn1 may normally counteract Shh-mediated activation.

Ectopic and/or increased environmental Ntn1 levels may trigger premature migration towards the midline. In E14.5 r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants, only a subset of pontine neurons split from the stream and entered the alternative ventral migratory pathway at the level of the ectopic Ntn1+ domain (Fig. 1I, fig. S5), suggesting that AES neurons may display intrinsic differential responsiveness to Ntn1 signaling. To fate map the contributions of r6 (r6RLP) or r7–8 (r7-8RLp) lower rhombic lip-derived neuronal progenies into the pontine stream and nuclei (Fig. 2, B, C and H, fig. S3), we crossed floxed reporter lines to r5–6::Cre or r7post::Cre (Cre is expressed up to the r6/r7 boundary; fig. S3H) in which Cre is down-regulated before AES migration (fig. S4). r6RLP mapping was confirmed by the tamoxifen-inducible MafB::CreERT2 transgenic line, whose reporter expression pattern is restricted to r5–r6, similar to r5–6::Cre (10, fig. S3). To trace the whole precerebellar lower rhombic lip progeny (r6-8RLp), we used r5post::Cre (figs. S3A and S4).

r6-8RLp contributed to the whole pontine nuclei (fig. S3), whereas r6RLP mapped to the most anterior (arrow; Fig. 2H, fig. S3), and r7-8RLp filled the remaining posterior portions of pontine nuclei (fig. S3). This topographic organization of pontine neuronal subsets directly correlated with their relative position within the migratory stream. Namely, r6RLp mapped to the dorsalmost AES, whereas r7-8RLp contributed to the remaining portion ventrally to r6RLp (Fig. 2, B and C). Thus, the precerebellar lower rhombic lip is rostrocaudally mapped onto the AES dorsoventral axis (Fig. 3E, fig. S1J) and, in turn, onto the PN rostrocaudal axis (fig. S1K), with neuronal subsets maintaining their relative position throughout migration and settling.

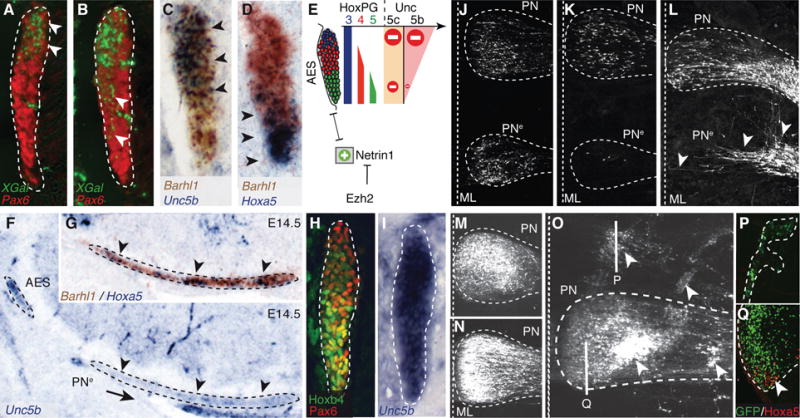

Fig. 3. Ezh2 and Hox dependent regulation of Unc5b in pontine neuron migration.

(A to B) X-gal (green)/Pax6 (red) co-stainings of E14.5 Unc5bbGal/+ heterozygotes (A) and Unc5bbGal/bGal homozygotes (B) showing X-gal-stained cell distribution in anterior extramural stream (AES) (arrowheads). (C to E) Unc5b/Barhl1 (C) and Hoxa5/Barhl1 (D) in situ hybridization in E14.5 AES showing complementary dorsoventral expression of Unc5b and Hoxa5 (arrowheads) and summary (E). (F to G) In r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants, ectopic pontine nuclei (PNe) migrating neurons are Unc5b-negative (F) and Hoxa5+/Barhl1+ (G) (arrowheads). (H to I) In E14.5 Hoxa5−/−/Hoxb5−/−/Hoxc5−/− AES, Unc5b is up-regulated ventrally (I), while Hoxb4/Pax6 are normally expressed (H). (J to K) In utero electroporation (EP) in E14.5 r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants of Unc5b/Unc5c/eGFP strongly reduces at E18.5 ectopically migrating PNe neurons (K), as compared to EP of eGFP (J), partially rescuing the phenotype. (L to Q) In E13.5 wild type, EP of Ntn1 results in posterior ectopic pontine neuron migration at E17.5, phenocopying r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (arrowheads, L). While EP at E13.5 of eGFP (M) or Unc5c/eGFP has no apparent effect on migration at E18.5 (N), EP of Unc5b/eGFP results in anterior ectopic migration and/or dorsal-lateral arrest (arrowheads, O). Immunostaining on sagittal sections shows that anterior ectopic GFP+/Unc5b+ electroporated cells are Hoxa5-negative (P); Hoxa5+ cells are normally restricted in posterior PN (Q).

Next, we investigated molecular correlates of this intrinsic cellular regionalization and asked whether Hox paralog group (PG)2–5 maintain their spatially-restricted progenitor expression patterns in pontine migratory stream and nuclei (Fig. 2). Indeed, Hox PG2 (Hoxa2/Hoxb2) and PG3 (Hoxa3/Hoxb3), expressed in the whole precerebellar rhombic lip, were correspondingly maintained throughout the pontine migratory stream and nuclei (6) (fig. S1). Hoxb4 is normally expressed up to the r6/r7 boundary, whereas the Hox PG5 rostral expression limit is posterior to PG4 genes (2). In the AES and PN, Hoxb4+ neurons extended just ventrally and posteriorly, respectively, to r6RLP (Fig. 2, C and D, fig. S1L), whereas Hoxa5 and Hoxb5 transcripts and Hoxa5 protein mapped to the ventralmost migratory stream and posteriormost pontine nuclei, respectively (Fig. 2A, F, H and I, fig. S1 and S2). Simultaneous detection of Hoxa5 and ZsGreen in r5–6::Cre;R26RZsGreen specimen demonstrated rostrocaudal segregation of r6RLp and Hoxa5+ neurons within the pontine nuclei (Fig. 2H). To permanently label Hoxa5-expressing neurons, we generated a transgenic line in which Cre was inserted in-frame at the Hoxa5 locus (Hoxa5::Cre) (10) (fig. S3). Hoxa5::Cre-expressing neurons segregated to the ventralmost AES and posteriormost PN, faithfully overlapping endogenous Hoxa5 distribution (Fig. 2, D, E, F and G, figs. S1F, S3 and S4). Thus, pontine neuron subsets of distinct rostrocaudal origin maintain their relative topographic positions and Hox codes throughout migration and settling within the target nucleus (Fig. 4A, fig. S1).

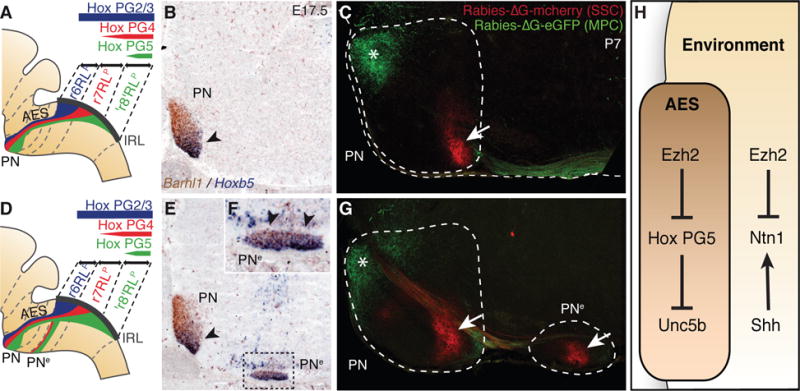

Fig. 4. Pontine nuclei regionalization and patterned cortical input.

(A, B, D, E and F), Hox expression summary in migrating pontine neurons of control (A) and r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (D). Barhl1/Hoxb5 in situ hybridization on E17.5 sagittal sections (B,E,F). In r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (E,F), Hoxb5+ neurons spread throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the ectopic nucleus (PNe) (arrowheads, F), while in PN they are normally posteriorly restricted as in control (arrowhead, B,E). (C and G) Rabies-ΔG viruses injected in control visual/medioposterior (MPC) and somatosensory (SSC) cortex anterogradely trace fibers into anterior (green,*) and posterior (red, arrow) PN (C), respectively. In r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (G), PNe lacks innervation by MPC, while is innervated by SSC (arrow). H, Ezh2- and Hox-dependent genetic circuitry of intrinsic and extrinsic Unc5b/Ntn1 regulation.

Is Ezh2 required to maintain Hox nested expression in migrating pontine neurons and nuclei? In E14.5 Wnt1::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl and Hoxa2::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants, Hoxb4, Hoxa5 and Hoxb5 were ectopically expressed within the anterior lower rhombic lip and spread ventrodorsally throughout the pontine migratory stream (Fig. 2, L and M, figs. S2 and S7). Thus, by preventing Hox PG4 and PG5 expression in anterior precerebellar rhombic lip and migrating neuronal progeny, Ezh2-mediated repression contributes to the maintenance of molecular heterogeneity in the migratory stream. This, in turn, may underlie intrinsic differential response of migrating neuron subsets to environmental Ntn1.

Netrin-mediated attraction is counteracted by Unc5 repulsive receptors (12) and Unc5c inactivation results in variable ectopic migration of AES neurons (13). Unc5c is expressed in lower rhombic lip progenitors, downregulated in migrating neurons, and reactivated upon approaching the midline (fig. S9) (13). Thus, Unc5c is unlikely to confer dorsoventrally biased response of the AES to Ntn1. Unc5b has been involved in vascular development (14), though a role in neuronal development was not explored. We found a dorsoventral high-to-low density of cells expressing Unc5b (Fig. 3C, fig. S9), and b-galactosidase activity in Unc5bbGal/+ fetuses (Fig. 3A). Unc5b expression was in turn downregulated upon the migratory stream turning towards the midline (fig. S9C). Dorsoventral Unc5b transcript distribution in the migratory stream anti-correlated with Hox PG5 expression (Fig. 3, C and D). In E14.5 Hoxa5−/−;Hoxb5−/−;Hoxc5−/− compound mutants, Unc5b was up-regulated in ventral Hoxb4+/Pax6+ AES neurons (Fig. 3, H and I). Thus, Hox PG5 normally represses Unc5b in ventral AES neurons originating from posterior precerebellar lower rhombic lip.

In E14.5 Unc5bbGal/bGal null mutants, β-galactosidase+ cells partially lost their normal dorsal restriction and spread into ventral AES (Fig. 3B). Thus, Unc5b contributes to maintain topographical organization of dorsal AES subsets. In E16.5 Unc5c−/− fetuses, dorsal Unc5b expressing AES neurons maintained their normal migratory path, whereas ectopic neurons were Hox PG5+ and mainly Unc5b-negative (fig. S9). Therefore, in the absence of Unc5c, ventral Unc5b-negative AES neurons become more sensitive to Ntn1-mediated attraction than dorsal Unc5b-expressing neurons. Similarly, in r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants, Unc5b expressing neurons remain dorsal and pursue their normal migration, whereas Hox PG5+/Unc5b-negative neurons are preferentially influenced by Ntn1 upregulation and ectopically attracted to the midline (Fig. 3, F and G, fig. S2). Moreover, in Hoxa2::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants, in which all pontine neurons are Ezh2−/−/H3K27me3− and migrate through an environment ectopically expressing Ntn1 (fig. S5), all migrating neurons are prematurely attracted to an ectopic posterior midline position, are Hox PG5+, and down-regulate Unc5b (figs. S2 and S7).

Next, Unc5b/5c overexpression by in utero electroporation of E14.5 lower rhombic lip progenitors was sufficient to cell-autonomously rescue the PNe phenotype in r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants (eGFP+ neuron quantification in PNe compared to PN: eGFP (n=5) 33.79%±0.1060; eGFP/Unc5b/5c (n=5) 0.64%±0.0044; p=0.00011) (Fig. 3, J and K), demonstrating that elevating Unc5 receptor levels counteracts increased Ntn1-mediated attraction. Ntn1 overexpression by electroporation in E13.5 wild type fetuses induced ectopic posterior migration of AES neurons (Fig. 3L), partially phenocopying the r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutant phenotype, showing that increasing Ntn1 is sufficient to cause ectopic ventral migration of neuronal subsets.

Furthermore, while overexpression of Unc5c in E13.5 wild type fetuses had no apparent effect on AES migration (Fig. 3, M and N), Unc5b electroporation triggered ectopic anterior migration and/or block in dorsal position of Hoxa5-negative pontine neurons subsets (Fig. 3, O to Q). Therefore, maintaining constitutively high Unc5b levels in migrating neurons prevents or delays turning towards the midline, the latter resulting in ectopic anterior migration. Conditional Hoxa2 overexpression in rhombic lip derivatives by mating Wnt1::Cre with a ROSA26::(lox-STOP-lox)Hoxa2-IRES-EGFP (Wnt1::Cre;R26RHoxa2) (10) allele also resulted in anterior ectopic migration generating rostrally elongated pontine nuclei, which maintained high Unc5b expression, unlike in controls (fig. S9). Therefore, while Hox PG5 are involved in negatively regulating Unc5b in the ventral migratory stream, Unc5b expression in dorsal AES may be under Hox PG2 positive regulation generating differential responses to environmental Ntn1.

Finally, we investigated whether the PN and PNe patterning differences in r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants result in distinct cortical inputs. In P7 Pcp2::Cre;R26RtdTomato animals (10) expressing Cre in medio-posterior (including visual) cortex (MPC), tdTomato+ axons projected onto the rostral pontine nuclei, in agreement with (15), including the r6RLp neuron subset (fig. S6). Co-injection of rabies-ΔG-GFP and rabies-ΔG-mCherry into visual/MPC and medial somatosensory cortex (SSC) resulted in rostral GFP+ and caudal mCherry+ axonal inputs onto the pontine nuclei, respectively (Fig. 4C). In r5–6::Cre;Ezh2fl/fl mutants, PN was targeted both by visual/MPC-derived GFP+ (rostrally) and SSC-derived mCherry+ (caudally) axons, whereas PNe was innervated by SSC-derived though not visual/MPC-derived axons (Fig. 4G), correlating with their posterior Hox PG5+ profile (Fig. 4, A, B and D to F).

During radial migration, correlation to rostrocaudal position of origin is maintained through interaction with glial progenitors (16). How long-range tangentially migrating neurons (17) maintain information about their origin is less understood. We show that the topographic migratory program of r6–r8 derived pontine neurons is largely established in progenitor pools according to rostrocaudal origin and maintained in migrating neurons. We found similar organizational principles during lateral reticular nucleus migration (fig. S10). Moreover, the r2–r5 rhombic lip also gives rise to neurons that migrate tangentially along a short dorsoventral extramural path and populate distinct brainstem cochlear nuclei with a rostrocaudal topography (3). On its caudorostral route, the precerebellar stream migrates ventrally to the cochlear stream (3) though they do not mix despite close cellular proximity, suggesting that rhombomere-specific programs may control appropriate precerebellar neuron position during tangential migration. Indeed, we show that the topography of r6- versus r7- versus r8-origin is preserved throughout migration, mapped along the dorsoventral axis of the pontine stream and eventually within rostrocaudal subregions of the pontine nuclei, correlating with patterned cortical input. The transcriptional regulation of this tangential migratory program is epigenetically maintained (Fig. 4H). Ezh2-mediated repression maintains dorsoventrally-restricted environmental distribution of attractive/repulsive cues such as Ntn1 and an intrinsically heterogeneous Hox transcriptional program in the migratory stream that, in turn, provides neuronal subsets with distinct Unc5b-dependent responses to environmental Ntn1, thus contributing to maintain neuronal position during migration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Balint, F. Boukhtouche, Y.-Y. Lee, C.-Y. Liang, D. Kraus, T. Mathivet, F. Santagati, J.F. Spetz, A. Yallowitz, for technical support and discussion. We are grateful to M. Tessier-Lavigne, S.H. Orkin, E. Callaway, V. Castellani, P. Mehlen, O. Nyabi, J. Haigh for gift of mouse lines, probes, or reagents. T.D. is recipient of an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship. Work in FMR laboratory is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Sinergia CRSI33_127440), ARSEP, and the Novartis Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1229326/DC1

Materials and Methods

References (18–37)

References and Notes

- 1.Lumsden A, Krumlauf R. Science. 1996;274:1109–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tümpel S, Wiedemann LM, Krumlauf R. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;88:103–137. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)88004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farago AF, Awatramani RB, Dymecki SM. Neuron. 2006;50:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman J, Bayer SA. J Comp Neurol. 1987;257:529–552. doi: 10.1002/cne.902570405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez CI, Dymecki SM. Neuron. 2000;27:475–486. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisen MJ, et al. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yee KT, Simon HH, Tessier-Lavigne M, O’Leary DM. Neuron. 1999;24:607–622. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nóbrega-Pereira S, Marín O. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:i107–i113. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margueron R, Reinberg D. Nature. 2011;469:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Materials and methods are available as supplementary material on Science Online.

- 11.Bloch-Gallego E, Ezan F, Tessier-Lavigne M, Sotelo C. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4407–4420. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04407.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong K, et al. Cell. 1999;97:927–941. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim D, Ackerman SL. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2167–2179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5254-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu X, et al. Nature. 2004;432:179–186. doi: 10.1038/nature03080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leergaard TB, Bjaalie JG. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2007;1:211–223. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.1.1.016.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakic P. Science. 1988;241:170–176. doi: 10.1126/science.3291116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatten ME. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:511–539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.