Abstract

Z-DNA binding proteins (ZBPs) play important roles in RNA editing, innate immune response and viral infection. Structural and biophysical studies show that ZBPs initially form an intermediate complex with B-DNA for B–Z conversion. However, a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism of Z-DNA binding and B–Z transition is still lacking, due to the absence of structural information on the intermediate complex. Here, we report the solution structure of the Zα domain of the ZBP-containing protein kinase from Carassius auratus (caZαPKZ). We quantitatively determined the binding affinity of caZαPKZ for both B-DNA and Z-DNA and characterized its B–Z transition activity, which is modulated by varying the salt concentration. Our results suggest that the intermediate complex formed by caZαPKZ and B-DNA can be used as molecular ruler, to measure the degree to which DNA transitions to the Z isoform.

INTRODUCTION

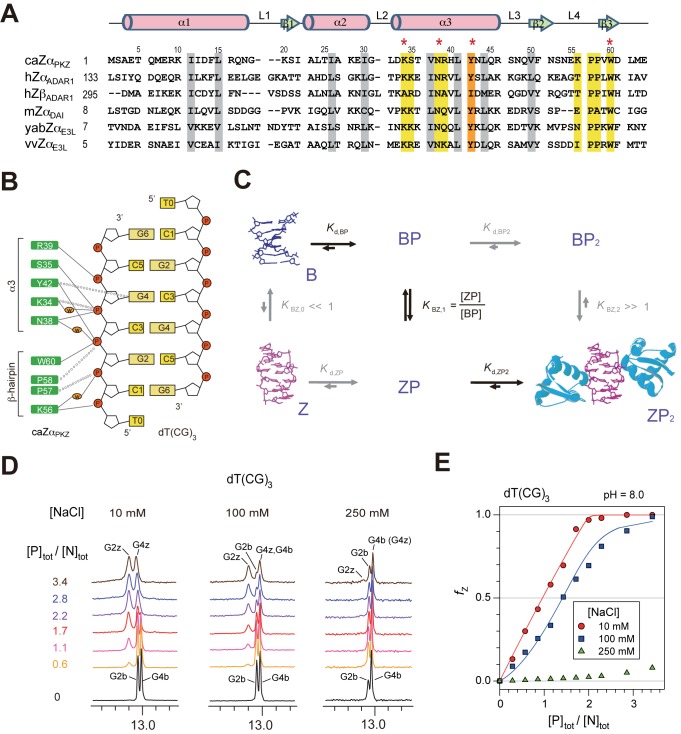

Left-handed Z-DNA is a higher energy conformation than B-DNA and forms under conditions of high salt, negative supercoiling and complex formation with Z-DNA binding proteins (ZBPs) (1–3). ZBPs have been identified in an RNA editing enzyme (ADAR1), DNA-dependent activator of interferon-regulatory factor (DAI, also known as DLM-1 and ZBP1), the viral E3L protein and a fish protein kinase containing a ZBP (PKZ) (Figure 1A) (4–7). The crystal structures of the Zα domains of human ADAR1 (hZαADAR1) (8), mouse DAI (mZαDLM1) (5) and yatapoxvirus E3L (yabZαE3L) (9), and Carassius auratus PKZ (caZαPKZ) (10) in complex with 6-base-paired (6-bp) dT(CG)3 revealed that two molecules of Zα bind to each strand of double-stranded (ds) Z-DNA, yielding 2-fold symmetry with respect to the DNA helical axis. The intermolecular interaction with Z-DNA is mediated by five residues in the α3 helix and four residues in the β-hairpin (β2-loop-β3) (Figure 1B). Among them, four residues (K34, N38, Y42 and W60; marked with asterisks in Figure 1A) show a high degree of conservation and play important roles in Zα function.

Figure 1.

Interaction of caZαPKZ with DNA and its dependence of NaCl concentrations. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of Z-DNA binding proteins. Numbering and secondary structural elements for caZαPKZ are shown above the sequence. Yellow and gray bars indicate residues important for Z-DNA recognition and protein folding, respectively. The key aromatic residue, tyrosine, is indicated by an orange bar. The asterisks indicate four highly conserved residues which play important roles in Zα function. (B) Residues of caZαPKZ involved in intermolecular interaction with dT(CG)3 reported in a previous study (10). Intermolecular H-bonds and van der Waals contacts indicated by solid lines and dashed lines, respectively. Three water molecules in key positions within the protein–DNA interface are indicated by orange ovals. (C) Mechanism for the B–Z conformational transition of a 6-bp DNA by two ZBPs. Black arrows indicate the primary transition mechanism. (D) 1D imino proton spectra of dT(CG)3 at 35°C upon titration with caZαPKZ in NMR buffer (pH = 8.0) containing 10 (left), 100 (middle) or 250 mM NaCl (right). The resonances from B-form are labeled as G2b and G4b and those from Z-form are labeled as G2z and G4z. (E) Relative Z-DNA populations (fZ) of dT(CG)3 induced by caZαPKZ at 10 (red circle), 100 (blue square) or 250 mM NaCl (green triangle) as a function of [P]tot/[N]tot ratio. Solid lines are the best fit of the emerging G2z resonance to Equation (8).

In addition, structural studies in solution suggested an active mechanism of B–Z transition of a 6-bp DNA induced by ZBPs, in which (i) the ZBP (denoted as P) binds directly to B-DNA (denoted as B); (ii) the B-DNA in the complex is converted to Z-form; and (iii) the stable ZP2 complex (the Z-form DNA denoted as Z) is produced by the addition of another P to ZP (Figure 1C) (11). In spite of these extensive structural studies (5,8–10), the detailed molecular mechanism of DNA binding and B–Z transition is still unclear due to the lack of structural data on the intermediate complexes. Therefore it is crucial to obtain structural snapshots and/or quantitative analyses of each step in the B–Z transition: B-DNA binding complex, transition complex and Z-DNA binding complex.

Studies of the exchange of imino protons, which reflect the structural and dynamic changes of base-pairs in DNA, have provided the dissociation constants and the equilibrium constant of B–Z transition of a 6-bp DNA induced by hZαADAR1 (11,12) and yabZαE3L (13). However, determination of the DNA-binding sites and conformational changes of ZBPs in each step of the B–Z transition, which relate to their affinities, has not been studied yet. The chemical shift perturbation of 15N-labeled proteins by ligand binding using heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) has been widely used to identify binding sites as well as to determine binding affinities (14). The NMR titration method has been applied mostly to one-site binding processes but the two-site or more binding systems have rarely been studied quantitatively. Recently, a novel quantitative method to analyze two-site protein interactions by NMR chemical shift perturbation has been described (15). Nevertheless, it is still very difficult to obtain accurate dissociation constants in the DNA–ZBP system, because the ZBPs bind to Z-DNA via a two-site DNA–protein interaction and also induce the B–Z conformational change in the DNA helix (Figure 1C).

In fish species, PKZs contain two Z-DNA binding domains (Zα and Zβ) to recognize heterogeneous DNAs (7,16–18). Although the overall structure of caZαPKZ and its interactions with Z-DNA are very similar to other ZBPs, the B–Z transition activity of caZαPKZ exhibits a unique dependence on NaCl concentration (denoted [NaCl]) (10). In addition, in contrast to other ZBPs, the unusual hydrogen bonding (H-bonding) interaction of caZαPKZ-K56 with the phosphate of Z-DNA is required for efficient Z-DNA binding (Figure 1B) (10). Thus the caZαPKZ–Z-DNA interaction is thought to be a good model system for the quantitative analysis of a two-site protein–DNA binding system including conformational change of DNA.

In this study, we determined the solution structure of the free form of caZαPKZ by multidimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy and performed NMR experiments on complexes of caZαPKZ with DNA duplexes, dT(CG)3 and d(CG)3, under various [NaCl]. We studied caZαPKZ–DNA interactions using imino proton and heteronuclear single-quantum correlation (HSQC) titrations, and determined the dissociation constants of caZαPKZ for B-DNA and Z-DNA binding and the equilibrium constant for the B–Z transition of DNA in the complex form. This provides the information about the chemical shift changes in caZαPKZ upon binding to B-DNA as an intermediate structure during B–Z transition. We also performed relaxation dispersion experiments to kinetically study the Z-DNA binding of caZαPKZ. We investigated changes in the binding affinity and hydrogen exchange of d(CG)3 complexed with caZαPKZ, in which the H-bonding interaction between Z-DNA and the K56 sidechain of caZαPKZ is interrupted. This study provides structural information on the intermediate complex formed by caZαPKZ and B-DNA, which plays an important role as molecular ruler by deciding the degree to which of the B–Z transition in DNA is induced by ZBPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

The DNA oligomers d(CG)3 and dT(CG)3 were purchased from M-biotech Inc. (the Korean branch of IDT Inc.), purified by reverse-phase HPLC, and desalted using a Sephadex G-25 gel filtration column. The coding sequence for residues 1–75 of caZαPKZ was cloned into E. coli expression plasmid pET28a (Novagen, WI, USA). Uniformly 13C/15N- and 15N-labeled caZαPKZ were obtained by growing the transformed BL21(DE3) bacteria cells in M9 medium that contained 15NH4Cl and/or 13C-glucose. The 13C/15N- and 15N-labeled caZαPKZ proteins were purified with a Ni –NTA affinity column and a Sephacryl S-100 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare, USA) on a GE AKTA Prime Plus. The amount of DNA was represented as the concentration of the double-stranded sample. The DNA and protein samples were dissolved in a 90% H2O/10% D2O NMR buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH = 6.0 or 8.0) and NaCl with concentration of 10, 100 or 250 mM.

NMR experiments

All of the 1H, 13C and 15N NMR experiments were performed on an Agilent DD2 700-MHz spectrometer (GNU, Jinju) or a Bruker Avance-III 800-MHz spectrometer (KBSI, Ochang) equipped with a triple-resonance cryogenic probe. All three-dimensional (3D) triple resonance experiments were carried out with 1.0 mM 13C/15N-labeled caZαPKZ protein. The imino proton and 1H/15N-HSQC spectra were obtained for complexes prepared by addition of 15N-labeled caZαPKZ to 0.1–0.2 mM DNA or addition of DNA to 1 mM 15N-labeled caZαPKZ. One dimensional (1D) NMR data were processed with either VNMR J (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or FELIX2004 (FELIX NMR, San Diego, CA, USA) software, while the two-dimensional and 3D data were processed with NMRPIPE (19) and analyzed with Sparky (20). External 2–2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate was used for the 1H, 13C and 15N references.

1H, 13C and 15N resonance assignments for caZαPKZ were obtained from the following 3D experiments in 10% D2O/90% H2O containing 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0) and 100 mM NaCl: CACB(CO)NH, HNCA, HNCACB, HNCO, HAHB(CO)NH, CB(CGCD)HD, CB(CGCCDCE)HE, HCCH-TOCSY, NOESY-1H/15C-HSQC, NOESY-1H/15N-HSQC and TOCSY-1H/15N-HSQC. The average chemical shift differences of the amide proton and nitrogen resonances between the two states were calculated by Equation (1):

|

(1) |

where ΔδH and ΔδN are the chemical shift differences of the amide proton and nitrogen resonances, respectively.

Solution structure calculation

The inter-proton distance restraints were extracted from NOESY-1H/15N-HSQC and NOESY-1H/13C-HSQC spectra. Backbone dihedral angle restraints were generated using TALOS+ (21). Only phi (φ) and psi (ψ) angle restraints which qualified as ‘good’ predictions from TALOS+ were used in the structure calculation. Hydrogen-bonds were introduced as a pair of distance restraints based on nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) analysis in combination with the prediction of protein secondary structural elements using the software CSI (22). Structure calculations were initially performed with CYANA 2.1, which combines automated assignment of NOE cross-peaks and structure calculation. On the basis of distance restraints derived from CYANA output, further structure calculations were carried out using CNS 1.3 in explicit solvent using the RECOORD protocol (23–25). The 10 lowest-energy structures were validated by PROCHECK-NMR (26). Structures were visualized using the program Discovery Studio 4.1 (BIOVIA, San Diego, CA, USA). Structural statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Structural statistics for the caZαPKZ structures.

| NOE upper distance limits | 878 |

| Intra-residual | 241 |

| Short-range (|i – j| = 1) | 312 |

| Medium-range (1 < | i – j | < 5) | 210 |

| Long-range (|i – j | > = 5) | 63 |

| Dihedral angle constraints | 109 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 27 × 2 |

| Violations | |

| Distances > 0.5 Å | none |

| Dihedral angles > 5° | none |

| Ramachandran analysis (%) | |

| Most favored regions | 79.3 |

| Additionally allowed regions | 15.5 |

| Generously allowed regions | 5.2 |

| Disallowed regions | 0.0 |

| R.M.S.D. from mean structure (structured region)a | |

| Backbone (Å) | 0.57 ± 0.18 |

| Heavy atom (Å) | 1.04 ± 0.21 |

aResidues in the structured region: 6–61.

Nitrogen Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion

The 15N amide Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion experiments were performed using free 15N-labeled caZαPKZ and 15N-labeled caZαPKZ complexed with dT(CG)3 at 35°C. Experiments employed a constant relaxation delay (Trelax) of 60 ms and 11 values of νCPMG = 1/(2τCP) ranging from 33 to 900 Hz, τCP is the delay between consecutive pulses. Transverse relaxation rates R2,eff were calculated for each cross-peak signal at each value by:

|

(2) |

where I(νCPMG) and I0 are the peak intensity at values of νCPMG with of 60 and 0 ms, respectively. For evaluation of average and standard deviation of R2,eff values, three or four different datasets were measured.

In the free caZαPKZ, the relaxation dispersions derived from residues in fast exchange on the NMR chemical shift timescale were fitted to (27):

|

(3) |

where R02 is the intrinsic transverse relaxation rate; Φex,f = pApB(Δωf)2, where Δωf is chemical shift difference between states A and B and pA and pB are the relative populations of states A and B, respectively; and kex,f the exchange rate between states A and B. The caZαPKZ in the complex with Z-DNA shows two kinds of independent exchange processes, the conformational exchange of free protein and the association/dissociation of Z-DNA. In this case, the relaxation dispersion data of the caZαPKZ complexed with dT(CG)3 (R2,effcomp) could be expressed by Equation (4):

|

(4) |

where R02 is the intrinsic transverse relaxation rate; Φex,b = pbpu(Δωbound)2, where Δωbound is chemical shift difference between the bound and unbound states and pb and pu are the relative populations of the bound and unbound states, respectively; and kex,b the exchange rate between the bound and unbound states (28).

Binding models

Accordingly, the HSQC titration curves were analyzed by assuming an active model of B–Z transition (Figure 1C), where P is the free forms of caZαPKZ, BP and ZP are the singly bound forms to B-DNA and Z-DNA, respectively, ZP2 is the doubly bound form to Z-DNA, and B is the B-form of free dT(CG)3. The concentrations of B, BP, ZP and ZP2 forms, [B], [BP], [ZP] and [ZP2], respectively, are described as:

|

|

|

|

(5) |

where [N]tot is the total concentration of DNA duplex; Kd,BP and Kd,ZP2 are the dissociation constants for the BP and ZP2 complexes, respectively; KBZ,1 ( = [ZP]/[BP]) is the equilibrium constant between BP and ZP forms; and [P] is the concentration of the free caZαPKZ, which is a solution of the following cubic equation:

|

(6) |

|

|

|

where [P]tot is the total concentration of caZαPKZ. The closed-form solution of Equation (6) has been reported (29):

|

(7) |

where,

|

The observed 1H and 15N chemical shift difference referenced to the free caZαPKZ, Δδobs, is described as:

|

(8) |

where ΔδB and ΔδZ are the 1H and 15N chemical shift differences of the B-DNA- and Z-DNA-bound forms relative to the free form, respectively. The relative Z-DNA population (fZ) could be determined from the integration of new resonances in the 31P NMR or imino proton spectra, which provide the same results (11). The observed fZ value determined from imino proton resonances is described as:

|

(9) |

Hydrogen exchange rate measurement

The apparent longitudinal relaxation rate constants (R1a = 1/T1a) of the imino protons of free and bound DNA were determined by semi-selective inversion recovery 1D NMR experiments. The hydrogen exchange rate constants (kex) of the imino protons were measured by a water magnetization transfer experiment with 20 different delay times (30,31). The kex values for the imino protons were determined by fitting the data to Equation (10):

|

(10) |

where I0 and I(t) are the peak intensities of the imino proton at times zero and t, respectively, and R1a and R1w are the apparent longitudinal relaxation rate constants for the imino proton and water, respectively (30–32).

RESULTS

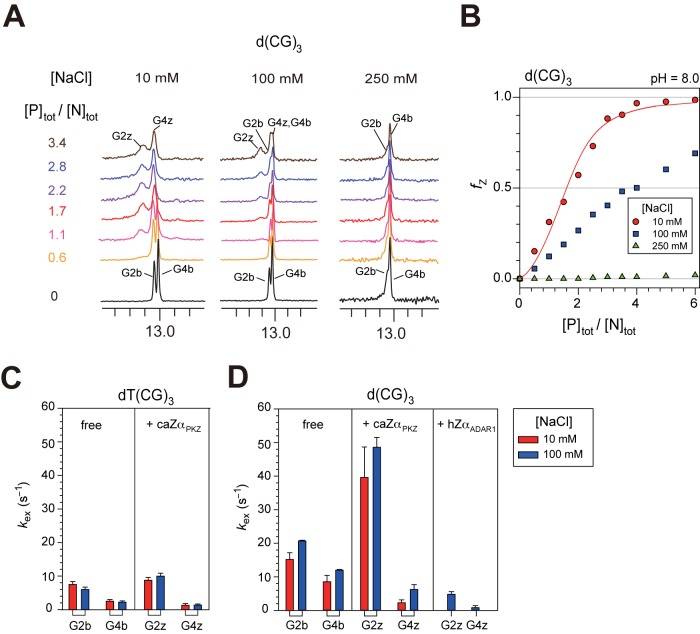

Titration of caZαPKZ into dT(CG)3 under various [NaCl]

Figure 1D shows the changes in the imino-proton spectra of dT(CG)3 upon titration with caZαPKZ at 35°C. The relative populations of Z-DNA (fZ) in dT(CG)3 were determined by integration of the new G2z resonance, as a function of the total protein: total DNA duplex ([P]tot/[N]tot) ratio (Figure 1E). CaZαPKZ exhibited a severe decrement in B–Z transition activity as [NaCl] increased. Most of the dT(CG)3 was in the Z-conformation at [P]tot/[N]tot > 2.0 at 10 mM NaCl. However, at [NaCl] = 100 mM, only about 67% of dT(CG)3 displayed the Z-DNA conformation at [P]tot/[N]tot = 2.0 (Figure 1E), in contrast to previous findings that most of d(CG)3 was converted to Z-DNA by hZαADAR1 (11) and yabZαE3L (13) under the same conditions. Interestingly, when [NaCl] increased up to 250 mM, caZαPKZ showed extremely low B–Z transition activity to dT(CG)3 (Figure 1E).

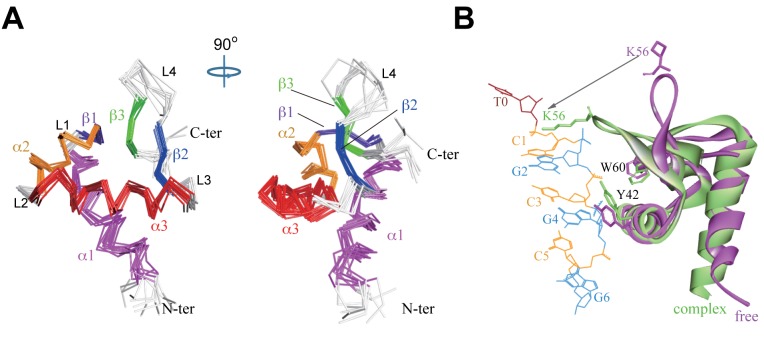

Solution structure of free caZαPKZ

In order to elucidate detailed structural information for free caZαPKZ, the solution structure of free caZαPKZ was determined by restrained molecular dynamics calculations using 878 distance restraints and 109 dihedral angle restraints collected at 100 mM NaCl (Table 1). A final set of 10 lowest energy structures was selected from 100 calculations, with no violations larger than 0.5 Å and 5° for the NOEs and dihedral angles, respectively (Figure 2A). The RMSD values for the backbone atoms in structured region was calculated to be 0.57 ± 0.18 Å. Free caZαPKZ is composed of three α-helices (α1, α2 and α3) and three β-strands (β1, β2 and β3) (Figure 2A). The ensemble of the 10 lowest energy structures shows that only the L4 loop in the β-hairpin (residues 53–57) is not well converged whereas all other loops are tightly structured (Figure 2A). Two consecutive prolines (P57 and P58) which have only limited numbers of restraints hinder to determine the precise orientation of the β-hairpin in solution structures. Figure 2B shows the superimposition of the lowest energy structure of free caZαPKZ and the crystal structure of the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex (10), where the β-hairpin exhibits bigger differences while no significant structural deviations were observed in other structural regions. The crystal structure showed that K56 sidechain in the β-hairpin of caZαPKZ is involved in H-bonding with the phosphate of Z-DNA in the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex (10) (Figure 2B). It might be possible that the orientation of the β-hairpin is restrained when the sidechain of K56 interacts with the backbone of Z-DNA.

Figure 2.

Solution structure of free caZαPKZ and comparison with other structures. (A) Superimposed backbone traces of the 10 lowest energy caZαPKZ structures. (B) Superimposition of the 3D structures of free caZαPKZ (violet) and caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex (PDB ID = 4KMF, pale green).

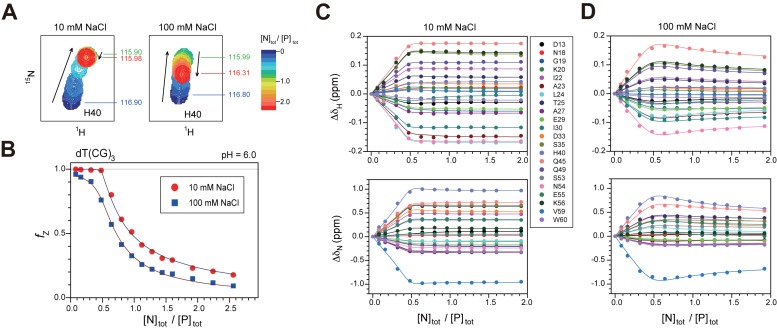

Chemical shift changes in caZαPKZ upon binding to dT(CG)3

In the 1H/15N-HSQC spectra of free caZαPKZ and caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 at 35°C, the amide resonances for several residues (N38, R39 and Y42) of the α3 helix disappeared altogether (Supplementary Figure S2), meaning they were in chemical exchange on an intermediate NMR time scale. Significant chemical shift changes were observed in other residues in the α3 helix as well as most residues in the β1–α2 and β-hairpin regions (Supplementary Figure S1), indicating the direct interaction of the sidechains of caZαPKZ with the phosphate backbone of dT(CG)3 as reported in the previous crystal structural study (10). As expected from the imino proton spectra at 250 mM NaCl, few chemical shift changes occurred upon exposure to dT(CG)3 (Supplementary Figure S1).

To further clarify the chemical shift perturbation results, the 1H/15N-HSQC spectra of caZαPKZ were acquired at 35°C as a function of the [N]tot/[P]tot ratio, where most amide cross-peaks showed significant movement (Supplementary Figure S2). Interestingly, the cross-peaks of some residues changed the direction of their movement after achieving a certain position (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure S2), indicating the presence of at least two binding modes. We analyzed the HSQC titration curves as well as the relative Z-DNA populations (fZ) assuming an active B–Z transition model (Figure 1C). Kd,BP and Kd,ZP2 are the dissociation constants of the BP and ZP2 complexes, respectively, and KBZ,1 ( = [ZP]/[BP]) is the equilibrium constant between the ZP and BP complexes. Because fitting each titration curve independently did not give reliable Kd values, all titration curves were fitted globally. During global fitting, we have fitted simultaneously all 1H and 15N titration curves with Equation (8) and the fZ data with Equation (9) to obtain accurate Kd values (Figure 3B–D). At 10 mM NaCl, the global fitting gave Kd,BP and Kd,ZP2 of 28 ± 17 and 345 ± 79 nM, respectively, and KBZ,1 of 0.87 ± 0.01 (Table 2 and Figure 3B and C). The dataset at 100 mM NaCl was globally fitted to obtain Kd,BP and Kd,ZP2 values of 16.4 ± 0.8 and 8.76 ± 0.67 μM, respectively, and KBZ,1 of 0.19 ± 0.01 (Table 2 and Figure 3B and D). These results indicate that the incrementation of [NaCl] from 10 to 100 mM leads to ∼600- and 25-fold larger Kd of caZαPKZ for B-DNA and Z-DNA binding, respectively, and 4.6-fold lower B–Z transition activity in the complex form (Table 2). The titration data at 250 mM NaCl could not be analyzed based on an active B–Z transition model, because of the extremely smaller KBZ,1.

Figure 3.

Quantitative assessments of DNA binding by caZαPKZ using HSQC data. (A) A representative region of the 1H/15N-HSQC of caZαPKZ upon titration with dT(CG)3 at 10 (left) or 100 mM NaCl (right). The cross-peak color changes gradually from blue (free) to red (bound) according to the [N]tot/[P]tot ratio. (B) Global fitting of the fZ data and (C and D) the 1H/15N-HSQC titration curves for caZαPKZ with dT(CG)3 as a function of [N]tot/[P]tot ratio. Data for the global fitting were derived from 1H (upper) and 15N (lower) chemical shift changes of HSQC cross-peaks of caZαPKZ at (C) 10 or (D) 100 mM NaCl. Solid lines are the best fits to Equation (8) (in B) or Equation (7) (in C and D).

Table 2. Dissociation constants (Kd,BP and Kd,ZP2) for B-DNA and Z-DNA binding, equilibrium constant for B–Z transition (KBZ,1) and association/dissociation rate constants (kon,ZP and koff,ZP2) for Z-DNA binding of caZαPKZ with a 6-bp DNA.

| DNA | pH | [NaCl] (mM) | Kd,BP (μM) | Kd,ZP2 (μM) | KBZ,1 | kon,ZP (×108 M−1s−1) | koff,ZP2 (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dT(GC)3 | 6.0 | 10 | 0.028 ± 0.017 | 0.345 ± 0.079 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 19.6 ± 1.2a | 675 ± 43a |

| 100 | 16.4 ± 0.8 | 8.76 ± 0.67 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 1.56 ± 0.03b | 1381 ± 30b | ||

| 8.0 | 10 | 0.157 ± 0.021 | 0.129 ± 0.074 | 1.18 ± 0.03 | |||

| 100 | 5.41 ± 0.66 | 2.41 ± 0.37 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | ||||

| d(GC)3 | 8.0 | 10 | 5.18 ± 2.43 | 1.79 ± 0.95 | 0.11 ± 0.05 |

aFrom CPMG data with Pfree = 0.873.

bFrom CPMG data with Pfree = 0.891.

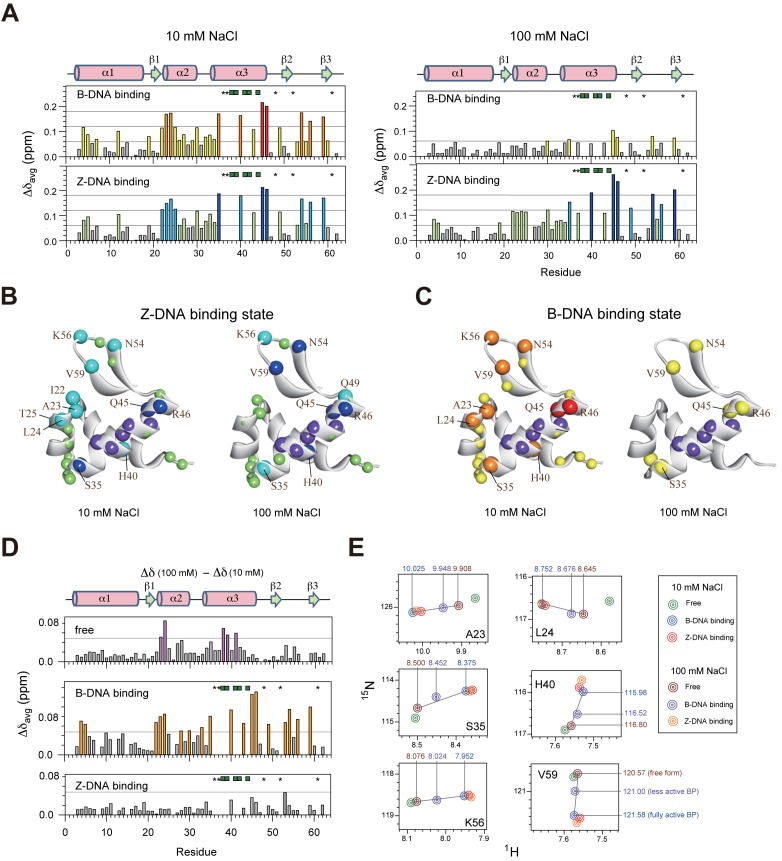

Chemical shift differences in caZαPKZ bound to B-DNA and Z-DNA

In addition to the dissociation constants, the global fitting method also provides the 1H and 15N chemical shift differences between the free and the bound forms for both B-DNA and Z-DNA binding (Supplementary Figure S3). The combined averages of 1H and 15N chemical shift changes (Δδavg) were determined for each residue to represent effects of binding to B-DNA and Z-DNA (Figure 4A). The chemical shift information for residues N38, R39, L41, Y42 and L44 in the α3 helix could not be collected because these resonances disappeared or became very weak during titration upon DNA. At 10 mM NaCl, both B-DNA and Z-DNA binding of caZαPKZ caused similar chemical shift perturbations, such that significant chemical shift changes were observed in the α3 helix as well as in the β1–α2 and β-hairpin regions (Figure 4A). However, at 100 mM NaCl, the B-DNA and Z-DNA binding of caZαPKZ exhibited completely different chemical shift perturbation results from each other (Figure 4A). For the Z-DNA binding, a large chemical shift changes were observed for the α3, β1–α2 and β-hairpin regions, similar to data at 10 mM NaCl (Figure 4A and B). On the other hand, the B-DNA binding affected I30 in L2; S35, Q45 and R46 in α3; and N54 and V59 in the β-hairpin with Δδavg > 0.06 ppm (Figure 4A and C). These results meant that the B-DNA binding state of caZαPKZ exhibited distinct structural features under high and low salt conditions, which might be related to reduced B–Z transition activity at higher [NaCl].

Figure 4.

DNA binding patterns differ with salt concentration and DNA conformation. (A) Histograms of the Δδavg values of 15N-caZαPKZ for the B-DNA and Z-DNA binding at 10 (left) or 100 mM NaCl (right). Residues whose cross-peaks disappear or become very weak during titration are represented with green square symbols. The asterisks indicate residues whose cross-peaks overlap with other resonances during titration. (B and C) Mapping the location of the residues having large Δδavg onto the NMR structure of free caZαPKZ for the (B) Z-DNA and (C) B-DNA binding at 10 (left) or 100 mM NaCl (right). The colors used to illustrate the Δδavg are: red or blue, >0.18 ppm; orange or cyan, 0.12–0.18 ppm; and yellow or pale green, 0.08–0.12 ppm (the same color coding is used in panel A). In both panels, the purple spheres indicate residues whose cross-peaks disappear or become very weak during titration. (D) The average chemical shift differences (Δδavg) between [NaCl] of 10 and 100 mM for free caZαPKZ (upper) and caZαPKZ complexed with B-DNA (middle) and Z-DNA (lower). (E) The calculated 1H/15N-HSQC cross-peaks of caZαPKZ complexed with B-DNA and Z-DNA in buffer containing 10 or 100 mM NaCl.

The superimposed 1H/15N-HSQC spectra of free caZαPKZ at 10, 100 or 250 mM NaCl at 25°C are shown in Supplementary Figure S4. Significant chemical shift differences were observed for residues in the α2 and α3 regions with increasing [NaCl] from 10 to 100 mM (Figure 4D). However, all residues in the Z-DNA binding complex showed little chemical shift changes (Δδavg < 0.05 ppm) upon change of [NaCl] (Figure 4D). For example, the A23 and L24 amide signals in the Z-DNA binding complex were located at the almost same position in the spectra (red and orange peaks in Figure 4E), whereas they showed the significant chemical shift differences in the free form (green and brown peaks in Figure 4E). These results indicate that the Z-DNA binding complex of caZαPKZ maintains almost the same structural features regardless of salt concentration, contrary to free caZαPKZ.

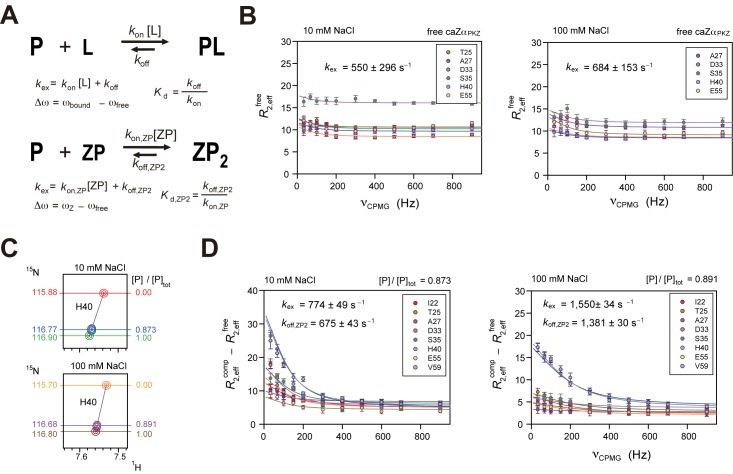

15N Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion experiment on caZαPKZ bound to dT(CG)3

The rate constants for association and dissociation of caZαPKZ with DNA were determined using NMR 15N backbone amide CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments (33). According to the concentrations of each state calculated using Equation (4) as a function of [N]tot/[P]tot, free P and complex ZP2 are the only two major conformational states when [N]tot/[P]tot << 0.5 (Supplementary Figure S5). Thus we analyzed the CPMG data using a two-state model of conformational exchange, where the ZP and ZP2 are considered as the ligand (L) and complex (PL), respectively (Figure 5A). In this model, the conformation exchange rate (kex) is given by kex = kon,ZP[ZP] + koff,ZP2, where kon,ZP is the association rate of ZP, koff,ZP2 is the dissociation rate of ZP2 and [ZP] is the concentration of ZP (Figure 5A). Interestingly, several residues of free caZαPKZ exhibited conformational exchange with kex of 550 ± 296 and 684 ± 153 s−1 at 10 and 100 mM NaCl, respectively (Figure 5B). Thus, in order to minimize the effect of conformational exchange of free caZαPKZ, the transverse relaxation rate differences between the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex and free caZαPKZ (R2,effcomp–R2,efffree) were fitted globally using Equation (4). The Δω values were determined from global fitting of the 1H/15N titration data and the relative population of free caZαPKZ, pfree ( = [P]/[P]tot) was calculated by pfree = 1 – Δδobs/ΔδZ (Figure 5C). Even though we used these fixed Δω and pfree values for fitting of the CPMG data, the all CPMG data were globally well fitted (Figure 5D). It indicates that the conformation exchange for the association/dissociation of Z-DNA exhibits the single kex value through all residues. At 10 mM NaCl, the CPMG dataset with pfree = 0.873 was globally fit to obtain the kex of 774 ± 49 s−1, which was used to calculate the kon,ZP[ZP] and koff,ZP2 of 98 ± 6 and 675 ± 43 s−1, respectively (using koff,ZP2 = kex × pfree) and the kon,ZP of (1.96 ± 0.12) × 109 M−1s−1 (using kon,ZP = koff,ZP2/Kd,ZP2) (Table 2 and Figure 5D). In the case that [NaCl] = 100 mM, the dataset at pfree = 0.891 was globally fitted to obtain the kex of 1550 ± 34 s−1 and the koff,ZP2 and kon,ZP of 1381 ± 30 and (1.56 ± 0.03) × 108 M−1s−1, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 5D). These results indicate that, as [NaCl] increased from 10 to 100 mM, the 13-fold slower kon,ZP and 2-fold faster koff,ZP2 resulted in a 25-fold larger Kd,ZP2.

Figure 5.

Quantitative assessments of DNA binding by caZαPKZ using CPMG data. (A) Two-state models of association/dissociation of a protein–ligand complex (upper) and the caZαPKZ–Z-DNA complex (lower). (B) The 15N CPMG NMR relaxation dispersion data for free caZαPKZ with [NaCl] of 10 (left) or 100 mM (right). (C) The simulated 1H/15N-HSQC cross-peaks of H40 of the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex at 10 (upper) or 100 mM NaCl (lower). The 15N chemical shifts and calculated [P]/[P]tot ratio are shown left and right of the spectra, respectively. (D) The 15N CPMG NMR relaxation dispersion data for the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex at 10 (left) or 100 mM NaCl (right). The microscopic rate constant (koff,ZP2) was extracted from kex and the [P]/[P]tot ratio.

H-bonding interaction of K56 with Z-DNA phosphate

The crystal structure of the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex showed that the sidechain of K56 exhibited an unusual H-bonding interaction with the T0pC1 phosphate of Z-DNA (Figure 1B) (10). Thus, in order to understand the role of this intermolecular H-bonding interaction, NMR titrations of caZαPKZ into d(CG)3 were performed (Figure 6A). At 10 mM NaCl, only 57% of d(CG)3 was converted to Z-DNA by caZαPKZ at [P]tot/[N]tot = 2.0 (Figure 6B), whereas most of dT(CG)3 exhibited the Z-DNA conformation at [P]tot/[N]tot ≥ 2.0 (Figure 1E). A similar decrement in B–Z transition activity was also observed at 100 mM NaCl (Figure 6B). We fitted simultaneously the 1H and 15N titration curves of caZαPKZ and the fZ data of d(CG)3 and dT(CG)3 at pH 8.0 to compare the B–Z transition activities of these two DNAs by caZαPKZ (Supplementary Figure S6). The global fitting showed that d(CG)3 has 33- and 14-fold larger values of Kd,BP and Kd,ZP2, respectively, and a 10-fold smaller KBZ,1 than dT(CG)3 at 10 mM NaCl (Table 2). When [NaCl] = 100 mM, the 1H/15N-HSQC titration data of d(CG)3 were not fitted well because of its very low B–Z transition activity (meaning KBZ,1 << 1). These results suggest that the intermolecular H-bonding interaction of K56 with the phosphate backbone of Z-DNA significantly contributes not only to DNA binding of caZαPKZ but also to its B–Z transition activity.

Figure 6.

Contribution of H-bonding interaction of K56 with Z-DNA phosphate to B–Z transition. (A) 1D imino proton spectra of d(CG)3 at 35°C upon titration with caZαPKZ in NMR buffer (pH = 8.0) containing 10 (left), 100 (middle) or 250 mM NaCl (right). The resonances from B-form are labeled as G2b and G4b and those from Z-form are labeled as G2z and G4z. (B) Relative Z-DNA populations (fZ) of d(CG)3 induced by caZαPKZ in NMR buffer containing 10 (red circle), 100 (blue square) or 250 mM NaCl (green triangle) as a function of [P]tot/[N]tot ratio. Solid lines are the best fit to Equation (8). (C) The exchange rate constants (kex) of the imino protons of the free dT(CG)3 (left) and caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 (right, [P]tot/[N]tot = 3.4) at 35°C. (D) The kex of the imino protons of the free d(CG)3 (left), caZαPKZ–d(CG)3, (middle, [P]tot/[N]tot = 6.0) and hZαADAR1–d(CG)3, (right, previous data (11)) at 35°C.

The hydrogen exchange rate constants (kex) for the imino protons of both free and caZαPKZ-bound dT(CG)3 and d(CG)3 were determined at 35°C. The G2b and G4b protons of free dT(CG)3 have significantly smaller kex values compared to those of free d(CG)3 (Figure 6C and D), indicating that the flanking T residue of dT(CG)3 leads to greater stabilization of the central G·C base-pairs. In the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex, the kex of G4z are significantly smaller than those of free dT(CG)3, whereas the G2z imino protons have slightly larger kex than the corresponding G2b protons (Figure 6C). Surprisingly, the G2z in the caZαPKZ–d(CG)3 complex has significantly larger kex than in the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex (Figure 6D), consistent with severe line-broadening of the G2z imino resonance (Figure 6A). These results indicate that the intermolecular H-bonding interaction of K56 plays an important role in stabilization of the G2·C5 base-pair in Z-DNA.

DISCUSSION

The caZαPKZ protein requires low salt concentration for full B–Z transition activity, although its overall structure and interactions with Z-DNA are similar to other ZBPs. It has been reported that the typical intracellular salt concentration of fresh water fish is maintained at as few as 10 mM (34,35), and goldfish showed low salinity tolerance (<20 ppt) (36). Thus the salt-dependent B–Z transition activity of caZαPKZ is thought to reflect the natural environmental conditions of goldfish. We have undertaken a structural analysis of protein–DNA interactions during B–Z transition of a 6-bp DNA by caZαPKZ, in order to understand the salt-dependency of ZBP activity. The NMR chemical shift perturbation (Supplementary Figure S1) and crystal structure analyses (10) can only illustrate the interactions of ZBP with Z-DNA in the final caZαPKZ–Z-DNA (ZP2) complex. However, by applying global analysis on the titration curves, we are able to provide structural information on caZαPKZ not only in the Z-DNA binding complex but also in the B-DNA binding complex that is the first intermediate structure in the B–Z transition pathway (Supplementary Figure S3). Global analysis gave the Kd of caZαPKZ for the BP (28 nM) and ZP2 complexes (345 nM) under 10 mM NaCl condition (Table 2), which have orders of magnitude similar to the previous Kd (851 nM) determined by bio-layer interferometry (10). The values of kon,ZP (1.96 × 109 M−1s−1) and koff,ZP2 (675 s−1), which are supported by fast exchange behavior in the 1H/15N-HSQC spectra during titration (Supplementary Figure S2), are consistent with the association process of 109–1010 M−1s−1 reported for protein–nucleic acid interactions (15,37–39). Taken together, we conclude that the analysis of CPMG data combined with global fitting of titration curves is the most effective method to estimate accurate dissociation constants as well as dissociation/association rate constants in a multi-site protein–DNA binding system including conformational changes of DNA and/or proteins.

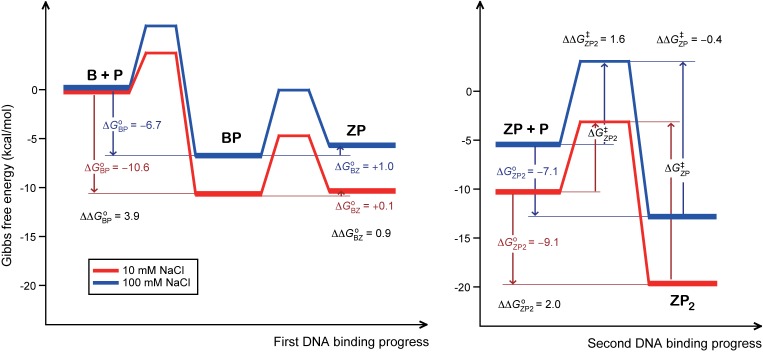

The increase of [NaCl] from 10 to 100 mM exhibits a larger effect on the kon,ZP (13-fold larger) than koff,ZP2 (2-fold larger), and this resulted in a 25-fold larger Kd,ZP2 (Table 2). Similar results were observed for the binding of Fyn SH3 domain to substrate peptides (40). The Gibbs free energies for the formation of ZP2 can be calculated using the equation ΔGoZP2 = RTlnKd,ZP2. The results revealed that the difference between the ΔGoZP2 values at 10 and 100 mM NaCl (ΔΔGoZP2 = ΔGoZP2100mM – ΔGoZP210mM) is +2.0 kcal/mol (Figure 7). The activation energy differences for association (ΔΔG‡ZP2) and dissociation (ΔΔG‡ZP) of the ZP2 complex can be evaluated using the equations, ΔΔG‡ZP2 = –RTln(kon,ZP100mM/kon,ZP10mM) and ΔΔG‡ZP = –RTln(koff,ZP2100mM/koff,ZP210mM), respectively. The CPMG data revealed that the ΔΔG‡ZP2 value was 1.6 kcal/mol whereas ΔΔG‡ZP was only −0.4 kcal/mol (Figure 7), which could be explained by the structural feature that, in the Z-DNA binding complex, caZαPKZ maintains almost the same backbone conformations regardless of salt concentration (Figure 4D). However, the free form of caZαPKZ shows unusual conformational exchange (Figure 5B), which displays distinct 1H/15N-HSQC spectra with varying salt concentration (Supplementary Figure S4). This structural feature is consistent with the CPMG data showing that, in spite of a 2-fold larger koff,ZP2, the Kd,ZP2 value increased 25× larger as [NaCl] increased from 10 to 100 mM (Table 2). Thus, our study suggested that increasing the ionic strength more strongly interferes with the association of ZP with caZαPKZ via the intermolecular electrostatic interactions (related to kon,ZP) rather than the dissociation of ZP2 (related to koff,ZP2).

Figure 7.

Quantitative description of the energy landscape of the first (lef) and second DNA binding (right) of caZαPKZ at 10 (red) or 100 mM NaCl (blue). Gibbs free energies for the DNA binding and B–Z transition steps were calculated using the equation, ΔGo = RTlnKd, where R is the gas constant and Kd is the dissociation constant for DNA binding (Kd,BP or Kd,ZP2) or ΔGo = –RTlnKBZ,1, where KBZ,1 is the equilibrium constant for B–Z transition. The activation energy difference (ΔΔG‡ZP2) for the Z-DNA binding of caZαPKZ between 10 and 100 mM NaCl condition was calculated using the equation, ΔΔG‡ZP2 = ΔG‡ZP2100mM – ΔG‡ZP210mM = –RTln(kon,ZP100mM/kon,ZP10mM), where kon,ZP10mM and kon,ZP100mM are the association rate constants for Z-DNA binding of caZαPKZ at 10 and 100 mM NaCl, respectively.

Surprisingly, we found that the structural features of the B-DNA binding complexes (BP) of caZαPKZ at 10 and 100 mM NaCl are completely different from each other (Figure 4D). At 10 mM NaCl, the α3, β1–α2 and β-hairpin regions of caZαPKZ participate in strong intermolecular interactions with B-DNA (Figure 4B). This intermolecular interaction in the BP complex is able to provide efficient driving force to cause the B–Z conformational change of DNA. However, as [NaCl] increased to 100 mM, the caZαPKZ binds to B-DNA mainly through the α3 helix, with a partial contribution of the β-hairpin (Figure 4B). Global analysis found that increasing [NaCl] from 10 to 100 mM more significantly reduced the Gibbs free energies for the formation of BP with ΔΔGoBP of 3.9 kcal/mol, which is 2-fold larger than the ΔΔGoZP2 value (Figure 7). It is reported that the activity of nitrogen regulatory protein C can be modulated by mutations or BeF3−, which drive the equilibrium toward the active state through destabilizing the inactive state and stabilizing the active state, respectively (41). Assuming that caZαPKZ binds to B-DNA to form a fully active BP conformation at low salt concentration, increasing the ionic strength screens the intermolecular electrostatic interactions, which participates in formation of the active BP conformation, and then the conformational equilibrium is driven toward the inactive state. As shown in Figure 4E, the ∼25– 40% chemical shift movements of caZαPKZ upon B-DNA binding, reflecting a lower population of the active BP conformation, can explain the relatively lower B–Z transition activity (4.5-fold smaller KBZ,1) (Table 1). Thus, the HSQC spectra of the intermediate BP complex derived from our global analysis could be used as a molecular ruler to determine the degree of B–Z transition activity of caZαPKZ (Figure 4E).

The hydrogen exchange data of the imino protons indicates that the G·C base-pairs in the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex are less stable compared to the hZαADAR1–d(CG)3 complex (Figure 6C and D). This might be caused by the lack of H-bonding interaction of caZαPKZ with the C5pG6 phosphate of DNA (Figure 1B), which is provided by the K170 sidechain of hZαADAR1 (8). Under low salt conditions, this H-bonding interaction of ZBP rarely affects the DNA binding as well as B–Z transition. In contrast, the H-bonding of K56 with DNA phosphate contributes to not only stabilization of base-pairs in Z-DNA but also DNA binding and B–Z transition (Figure 6). Because the backbone of the β-hairpin in free caZαPKZ is distinct from that of the complex structure (Figure 2B), this interaction plays an important role in stabilizing the contact of the β-hairpin with Z-DNA in order to achieve full activity of the ZBP. In hZαADAR1, both the free and complex forms have similar β-hairpin structures (8,42) and thus this interaction is not crucial for the function of the human protein.

In summary, we have performed a structural analysis of the interaction of ZBP caZαPKZ with DNA during B–Z transition. The solution structure of free caZαPKZ revealed that the overall structure is very similar to the caZαPKZ–dT(CG)3 complex while the β-hairpin exhibits the different orientation from the crystal structure. Global analysis of chemical shift perturbations found that increasing [NaCl] from 10 to 100 mM reduced the binding affinity of caZαPKZ for both B-DNA (600-fold) and Z-DNA (25-fold) and decreased its B–Z transition activity (4.6-fold). Our results suggest that the structure of the intermediate complex formed by caZαPKZ and B-DNA is modulated by varying salt concentration and thus it could be used as a molecular ruler to determine the degree of B–Z transition.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 2RVC). Chemical-shift assignments have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRM ID: 11595).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the GNU Central Instrument Facility for performing NMR experiments and Melissa Stauffer, of Scientific Editing Solutions, for editing the manuscript. This work is dedicated to the memory of the late Prof. Alexander Rich of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Research Foundation of Korea [2010-0020480, 2013R1A2A2A05003837, 2012R1A4A1027750 (BRL) to J.-H.L.; 2015R1C1A1A02036725 to C.-J.P.] funded by the Korean Government (MSIP); Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program [SSAC, No. PJ01117701 to J.-H.L.]; Samsung Science and Technology Foundation [SSTF-BA1301-01 to K.K.K]. Funding for open access charge: National Research Foundation of Korea; Gyeongsang National University.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herbert A., Rich A. The biology of left-handed Z-DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:11595–11598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbert A., Rich A. Left-handed Z-DNA: structure and function. Genetica. 1999;106:37–47. doi: 10.1023/a:1003768526018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rich A., Zhang S. Z-DNA: the long road to biological function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003;4:566–572. doi: 10.1038/nrg1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbert A., Alfken J., Kim Y.G., Mian I.S., Nishikura K., Rich A. A Z-DNA binding domain present in the human editing enzyme, double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:8421–8426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz T., Behlke J., Lowenhaupt K., Heinemann U., Rich A. Structure of the DLM-1-Z-DNA complex reveals a conserved family of Z-DNA-binding proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nsb0901-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim Y.-G., Muralinath M., Brandt T., Pearcy M., Hauns K., Lowenhaupt K., Jacobs B.L., Rich A. A role for Z-DNA binding in vaccinia virus pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:6974–6979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0431131100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothenburg S., Deigendesch N., Dittmar K., Koch-Nolte F., Haag F., Lowenhaupt K., Rich A. A PKR-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase from zebrafish contains Z-DNA binding domains instead of dsRNA binding domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:1602–1607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408714102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz T., Rould M.A., Lowenhaupt K., Herbert A., Rich A. Crystal structure of the Zα domain of the human editing enzyme ADAR1 bound to left-handed Z-DNA. Science. 1999;284:1841–1845. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha S.C., Lokanath N.K., Van Quyen D., Wu C.A., Lowenhaupt K., Rich A., Kim Y.G., Kim K.K. A poxvirus protein forms a complex with left-handed Z-DNA: crystal structure of a Yatapoxvirus Zα bound to DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:14367–14372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405586101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim D., Hur J., Park K., Bae S., Shin D., Ha S.C., Hwang H.Y., Hohng S., Lee J.H., Lee S., et al. Distinct Z-DNA binding mode of a PKR-like protein kinase containing a Z-DNA binding domain (PKZ) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:5937–5948. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang Y.-M., Bang J., Lee E.-H., Ahn H.-C., Seo Y.-J., Kim K.K., Kim Y.-G., Choi B.-S., Lee J.-H. NMR spectroscopic elucidation of the B-Z transition of a DNA double helix induced by the Zα domain of human ADAR1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11485–11491. doi: 10.1021/ja902654u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seo Y.-J., Ahn H.-C., Lee E.-H., Bang J., Kang Y.-M., Kim H.-E., Lee Y.-M., Kim K., Choi B.-S., Lee J.-H. Sequence discrimination of the Zα domain of human ADAR1 during B-Z transition of DNA duplexes. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:4344–4350. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee E.-H., Seo Y.-J., Ahn H.-C., Kang Y.-M., Kim H.-E., Lee Y.-M., Choi B.-S., Lee J.-H. NMR study of hydrogen exchange during the B-Z transition of a DNA duplex induced by the Zα domains of yatapoxvirus E3L. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:4453–4457. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fielding L. NMR methods for the determination of protein–ligand dissociation constants. Prog. NMR Spectrosc. 2007;51:219–242. doi: 10.2174/1568026033392705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arai M., Ferreon J.C., Wright P.E. Quantitative analysis of multisite protein-ligand interactions by NMR: binding of intrinsically disordered p53 transactivation subdomains with the TAZ2 domain of CBP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:3792–3803. doi: 10.1021/ja209936u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu C.Y., Zhang Y.B., Huang G.P., Zhang Q.Y., Gui J.F. Molecular cloning and characterisation of a fish PKR-like gene from cultured CAB cells induced by UV-inactivated virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2004;17:353–366. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su J., Zhu Z., Wang Y. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression analysis of the PKZ gene in rare minnow Gobiocypris rarus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008;25:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergan V., Jagus R., Lauksund S., Kileng Ø., Robertsen B. The Atlantic salmon Z-DNA binding protein kinase phosphorylates translation initiation factor 2α and constitutes a unique orthologue to the mammalian dsRNA-activated protein kinase R. FEBS J. 2008;275:184–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goddard T.D., Kneller D.G. SPARKY 3. San Francisco, CA: University of California; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wishart D.S., Sykes B.D. The 13C chemical-shift index: a simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J. Biomol. NMR. 1994;4:171–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00175245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brünger A.T., Adams P.D., Clore G.M., DeLano W.L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Jiang J.S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N.S., et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nederveen A.J., Doreleijers J.F., Vranken W., Miller Z., Spronk C.A., Nabuurs S.B., Güntert P., Livny M., Markley J.L., Nilges M., et al. RECOORD: a recalculated coordinate database of 500+ proteins from the PDB using restraints from the BioMagResBank. Proteins. 2005;59:662–672. doi: 10.1002/prot.20408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunger A.T. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laskowski R.A., Rullmannn J.A., MacArthur M.W., Kaptein R., Thornton J.M. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luz Z., Meiboom S. Nuclear magnetic resonance study of the protolysis of trimethylammonium ion in aqueous solution: order of the reaction with respect to solvent. J. Chem. Phys. 1963;39:366–370. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villali J., Pontiggia F., Clarkson M.W., Hagan M.F., Kern D. Evidence against the ‘Y-T coupling’ mechanism of activation in the response reculator NtrC. J. Mol. Biol. 2014;426:1554–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z.-X., Jiang R.-F. A novel two-site binding equation presented in terms of the total ligand concentration. FEBS Lett. 1996;492:245–249. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gueron M., Leroy J.L. Studies of base pair kinetics by NMR measurement of proton exchange. Methods Enzymol. 1995;261:383–413. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)61018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J.-H., Pardi A. Thermodynamics and kinetics for base-pair opening in the P1 duplex of the Tetrahymena group I ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2965–2974. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J.-H., Jucker F., Pardi A. Imino proton exchange rates imply an induced-fit binding mechanism for the VEGF165-targeting aptamer, Macugen. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1835–1839. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer A.G., Kroenke C.D., Loria J.P. Nuclear magnetic resonance methods for quantifying microsecond-to-millisecond motions in biological macromolecules. Methods Enzymol. 2001;339:204–238. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)39315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan I., Potts W., Oates K. Intracellular ion concentrations in branchial epithelial cells of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) determined by X-ray microanalysis. J. Exp. Biol. 1994;194:139–151. doi: 10.1242/jeb.194.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J., Eygensteyn J., Lock R., Bonga S., Flik G. Na+ and Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms in isolated chloride cells of the teleost Oreochromis mossambicus analysed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. J. Exp. Biol. 1997;200:1499–1508. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.10.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schofield P.J., Brown M.E., Fuller P.F. Salinity tolerance of goldfish,Carassius auratus, a non-native fish in the United States. Fla. Sci. 2006;69:258–268. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winter R.B., Berg O.G., von Hippel P.H. Diffusion-driven mechanisms of protein translocation on nucleic acids. 3. The Escherichia coli lac repressor-operator interaction: kinetic measurements and conclusions. Biochemistry. 1981;20:6961–6977. doi: 10.1021/bi00527a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park C., Raines R.T. Quantitative analysis of the effect of salt concentration on enzymatic catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11472–11479. doi: 10.1021/ja0164834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korennykh A.V., Piccirilli J.A., Correll C.C. The electrostatic character of the ribosomal surface enables extraordinarily rapid target location by ribotoxins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:436–443. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meneses E., Mittermaier A. Electrostatic interactions in the binding pathway of a transient protein complex studied by NMR and isothermal titration calorimetry. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:27911–27923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.553354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardino A.K., Villali J., Kivenson A., Lei M., Liu C.F., Steindel P., Eisenmesser E.Z., Labeikovsky W., Wolf-Watz M., Clarkson M.W., et al. Transient non-native hydrogen bonds promote activation of a signaling protein. Cell. 2009;139:1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schade M., Turner C.J., Kuhne R., Schmieder P., Lowenhaupt K., Herbert A., Rich A., Oschkinat H. The solution structure of the Zα domain of the human RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 reveals a prepositioned binding surface for Z-DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:12465–12470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.