Abstract

Pain is a multidimensional, complex experience. There are many challenges in identifying and meeting the needs of patients experiencing pain. Evaluation of pain from a bio-psycho-social-spiritual framework is particularly germane for patients approaching the end of life. This review explores the relation between the psychospiritual dimensions of suffering and the experience of physical pain, and how to assess and treat pain in a multidimensional framework. A review of empirical data on the relation between pain and suffering as well as interdisciplinary evidence-based approaches to alleviate suffering are provided.

Keywords: pain, psychological factors, spiritual factors, palliative medicine

The human experience of pain is complex, encompassing all aspects of personhood—physical, psychological, social connectedness and spiritual aspects.1 As such, adequate treatment of a patient’s pain requires an approach that addresses each of these components. Clinicians who cannot perceive and assess these elements are likely to have greater difficulty optimizing treatment. Each step of understanding the multidimensionality of pain is a critical component to providing the best pain management possible to patients, especially at the end of life.

Although the assessment and management of physical, psychological, and spiritual suffering faced by patients with life-limiting conditions are clinical skills central to the subspecialty of hospice and palliative medicine,2 the supply of palliative medicine specialists is inadequate to meet clinical demand.3 Nonspecialists usually are trained exclusively in the more traditional biologic model of pain assessment and treatment. Because pain treatment remains inadequate for many patients with life-limiting illness,4–6 the goal of this study was to present the use and application of a multidimensional pain assessment framework for all clinicians caring for populations of seriously ill individuals. Our framework begins by examining the concept of total pain and continues by addressing the roles of suffering and meaning making; it concludes by exploring both adaptive and maladaptive examples of coping with pain.

Multiple Dimensions of Pain

Concept of Total Pain

Dame Cicely Saunders, a physician, nurse, social worker, and founder of the modern hospice movement, coined the term “total pain” to describe the bio-psycho-social-spiritual phenomenon of a pain experience. She reviewed patients’ pain reports and found qualities of the pain experience that existed beyond physiologic descriptors such as intensity, location, nociceptive, or neuropathic. She began to integrate the concept of the indivisibility of physical and mental pain into her academic writings and clinical practice. Saunders noted that patients’ anxiety, depression, fear, concerns for their soon-to-be-bereaved family, and need for “meaning finding” influence the pain experience at the end of life.7,8 Saunders’s work highlighted the limitations of appropriate use of opioids and the potential role of patient narratives in the total pain experience.8

Meaning and Suffering

Overcoming suffering through meaning making is gaining recognition in the empirical literature.9,10 Viktor Frankl, a psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, was perhaps the first to study meaning making in the context of modern medicine. Frankl outlined three types of suffering: physical (pain, somatic diseases), psychological (emotional hardship, psychological disorders), and spiritual (lack of a meaningful life, moral dilemmas). During his imprisonment in Nazi concentration camps, Frankl noted that those who held on to their sense of meaning were able to maintain their physical and psychological resilience.11 This theoretical foundation has since been supported by longitudinal research showing that individuals with high levels of meaning in their lives are less likely to experience pain.10

Max Harvey Chochinov, a palliative psychiatrist, made early observations from his research with the Patient Dignity Inventory, which assessed the spiritual “landscape of distress in the terminally ill.” He found an inverse relation between “sense of meaning” and “intensity of distress.”12,13 Chochinov encouraged clinicians to assess the whole person when treating patients in palliative care.

Research on Spiritual Pain

Meaning making can affect the pain experience, can decrease inflammation, and can improve the ability to cope with pain.9,10,14 The psychospiritual process of meaning making can reduce stress on the body. Conversely, spiritual struggles increase physiological stress and promote increased morbidity and mortality.15 For some patients, the use of religious rubrics can be used to assist with meaning making in the context of an organized religion.16 For patients with a faith background, integrating these practices into their pain management strategies may be effective in reducing pain.17–22

As societies become increasingly secular, these traditional religious frameworks are less accessible to many patients. The lack of preestablished routes to meaning making leads some individuals to maladaptive approaches for interpreting suffering that can negatively affect their quality of life. Ironically, maladaptive searches for meaning, or lacking current meaning, may cause more psychophysiological stress than not searching at all.10 Among medically ill individuals who do not have an established religious framework to approach the concept of meaning making, better psychophysiological outcomes may occur if a psychotherapist can guide the search for meaning.10 For individuals who already experience high levels of personal meaning in their lives, however, continuing to search for new outlets of meaning may create additional psychophysiological stress and negative health outcomes among medically ill individuals.10

Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual Model of Pain

George Engel was the first to formally describe the bio-psycho-social model of disease.23 This model quickly became the gold standard through which mental health clinicians conceptualized and treated their patients24; however, the process of adoption was significantly slower among biomedical clinicians.25,26 The model goes beyond the Cartesian dualism that separates the “physical” from the “mental” experience. Conceptualizations that incorporate the bio-psycho-social model can explain how individuals may experience pain without an identified physiologic etiology or how they may experience differing pain levels compared with other individuals within the context of a recognized disease or injury process. The bio-psycho-social model encompasses interactions among medical, mental health (including the patient’s cognitive appraisals of his or her medical status), and sociological factors and how these affect a patient’s general well-being.

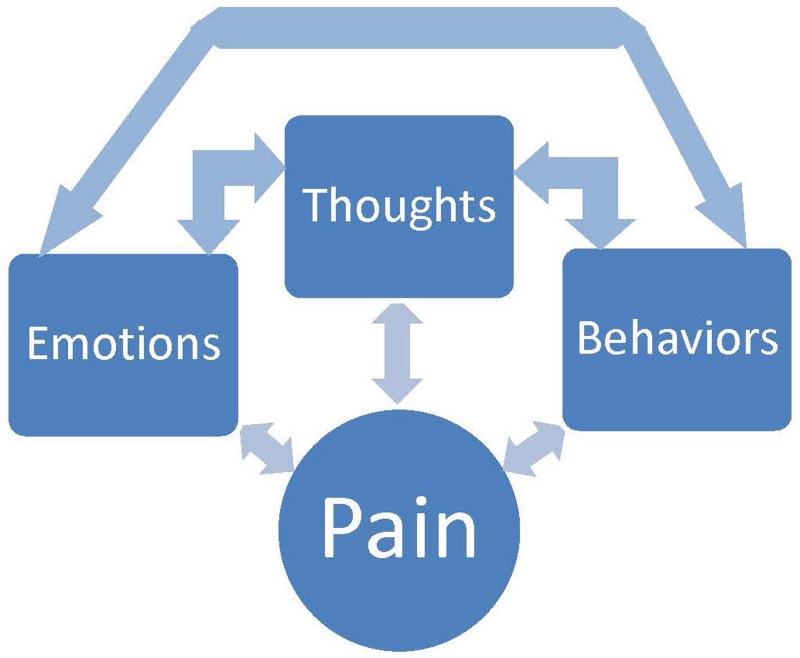

The gate control/neuromatrix theory of pain27,28 builds upon the bio-psycho-social model with direct application to the pain experience. It describes the bidirectional relation among the biological, psychological, and social aspects of the pain experience (Fig.). It examines how each domain may increase or decrease the pain experience via descending pathways from the brain modulating the ascending pain pathways.29 Multidisciplinary pain management continues to be informed by this theory of pain.

Fig.

Bidirectional pain pathways based on the gate control/neuromatrix pain theory.

Over time the empirical research evidence has supported the bio-psycho-social and gate control/neuromatrix models’ thesis that psychological status affects the level of pain experienced by the individual.30 Some of the psychological factors mediating the pain experience that have been identified include negative mood, anxiety, amount of social support, sense of self-efficacy and control, and adaptive coping strategies.31–34 These factors still fail to completely explain the observed variability across individuals’ experiences with pain, however.1,35,36

The bio-psycho-social-spiritual model recognizes the potential impact of spiritual and religious variables in mediating the biological and psychological experience of pain.20 Although religious and spiritual influences on a person’s experience of pain at the end of life are highly individualized and nongeneralizable in many ways, it is important for clinicians to understand key differences in the conceptualizations of pain and suffering in the context of the world’s major religions. Table 1 briefly summarizes the role of spiritual suffering, using potential cultural symbols of suffering in each of the five major world religions. This tool elucidates cultural and religious themes that may inform a clinician about a patient’s beliefs about death, dying, and the meaning of suffering.

Table 1.

Brief guide to potential religious dimensions of suffering at the end of life

| Religion | Origin/sacred text/ exemplar of suffering |

Core principles | Potential issues affecting meaical care at the end of life |

Afterlife |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judaism | Monotheistic Torah Job |

There is one God who is transcendent and omnipresent The Hebrews are God’s chosen people Failure to obey God is a sin Life is sacred |

Belief in the sanctity of life may lead to continued aggressive care Belief in the sanctity of the body at death may lead to avoidance of interventions (eg, surgery, feeding tubes) |

Because of intense debate among Rabbinical scholars, fear of the afterlife generally revolved around its uncertainty |

| Christianity | Monotheistic Bible Jesus |

Humans are sinful Jesus Christ is the Savior, who died on the cross and was resurrected Salvation is obtained through either faith or good deeds |

The belief in the possibility of a miracle sometimes leads to decisions to prolong aggressive medical interventions |

Guilt, unresolved sin, and issues of forgiveness and absolution can affect how the soul experiences the afterlife |

| Islam | Monotheistic Koran Job |

Islam means submission (to the will of God) There is one God, Allah, the creator of all; Mohammed is his prophet 5 Pillars of Islam:

|

Sanctity of life is paramount and its importance overrides obligations to the 5 Pillars of Islam |

After death, humans rest in the grave until the day of judgment, when Allah determines who will go to Paradise or Hell |

| Hinduism | Polytheistic Vedas Yogis |

Basic principles:

|

Some patients may fear anything that may cloud judgment at the end of life because they should focus on sacred things at the moment of death to ensure rebirth to a higher form of being Disease states such as delirium or medications such as opioids or benzodiazepines may be concerning to patient/family |

Fear of rebirth to a lower order because of bad karma or clouded state of mind at time of death |

| Buddhism | Nontheistic Mahayana sutras Boddhisattva |

Ultimate goal is to end the cycle of suffering 4 Noble Truths of Buddhism:

|

Patients may fear lack of clarity of mind during the dying process because the soul may get lost in the transition to the next life Concerns may arise around opioids, benzodiazepines, and disease states such as delirium and dementia |

Fear of the soul getting lost in transition from this life to the next, especially if delirious; after death, Buddhists believe the soul waits rebirth in 1 of 6 different states of being |

Adaptive and Maladaptive Religious and Spiritual Coping

Spirituality and religion are powerful forces, and their effects may be positive or negative. Positive (adaptive) spiritual practices positively influence the descending/central modulating pain pathways.37 Empirically validated manifestations of positive effects are stress and pain reduction, sense of support by a higher power, or feeling connected within a supportive social environment. Negative (maladaptive) spiritual practices (eg, interpretation of the pain experience as “God is punishing me”) increase pain sensitivity and reduce pain tolerance.38 There is evidence that serotonin receptor densities are correlated with spiritual tendencies, which suggests that engaging in spiritual practices may influence the serotonin pathways that regulate both mood and pain.39

Spiritual coping cannot be reduced simply to a variety of biological, psychological, and social elements.40 Spiritual coping can cause changes within a constellation of other factors that have been shown to affect pain tolerance. Specifically, research has identified three forms of religious coping related to locus of control, each with a unique adaptive or maladaptive impact.41 The first form of religious coping is “deferred” coping, in which the patient defers all aspects of his or her health to a higher power (eg, “I’m leaving it in God’s hands”). The second form is “collaborative,” in which the patient shares responsibility for his or her health with a higher power (eg, “God and I will get through this together/God will watch over me and it’s my responsibility to go to my doctor’s appointments/check blood sugars/get annual mammograms”). The third type is “self-directed,” in which the patient does not rely on a higher power at all (eg, “I’m on my own to make sure I stay healthy”). A fourth form of coping, identified by Phillips and colleagues,42 is the “abandoned” subtype, in which the person must take care of his or her own health because a higher power has abandoned the person (eg, “God won’t help me because I’m a bad person so I have to deal with it on my own”).

In general, the collaborative form of coping is associated with better mental and physical health outcomes.41,43–45 Although the self-directed coping group has been shown to have mixed results, those whose experience is aligned with the abandoned subtype often have strong negative outcomes.42 The deferred coping style is generally associated with more negative outcomes; however, at end of life, when there is limited control over the ultimate outcome, deferred coping is correlated with less agitation and a greater sense of peace.46–48

Pain Severity Versus Pain Tolerance

Generally speaking, religion and spirituality do not wipe away the experience of physical pain. Research shows that religious and spiritual practices have a greater influence on pain tolerance than on pain sensitivity.19,21,34 In other words, although the patient may not report a lower pain level, his or her spiritual resources allow engagement in more daily activities with his or her current pain level, and perhaps even require less pain medication while doing so. This is true across multiple dimensions of the pain spectrum. Positive spiritual practices increase tolerance in both chronic pain34,49 and acute pain situations.19

Clinical Assessment of Spirituality and Pain

Although a number of spiritual assessment tools exist for use in a clinical setting, few have been validated empirically. This list is far from complete, but it does provide a brief overview of available tools to identify how pain may be related to spiritual distress and where interdisciplinary interventions may be helpful for patients with chronic pain and in palliative care populations. In the context of a spiritual assessment, the physician is not expected to be a spiritual director or a psychologist; rather, the care provider is responsible for assessing these needs and consulting with appropriate professionals to ensure that the patient receives the support needed. Although physicians are not expected to meet a patient’s spiritual needs, they can facilitate access to services that the patient requires, just as they would make referrals to psychologists, physical therapists, dietitians, or other specialty providers.

Qualitative Spiritual Assessments and Pain

Many qualitative spiritual screening tools allow clinicians to make assessments that contribute to stronger consults with spiritual advisors, including HOPE (Hope, Organized Religion, Personal Spirituality Effects), FICA (Faith, Importance, Community, Application), and OASIS (Oncologist-Assisted Spiritual Intervention Study) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Qualitative screening tools for pain assessments

| Hope, Organized Religion, Personal Spirituality Effects (HOPE)48 |

Faith, Importance, Community Application (FICA)50 |

Oncologist-Assisted Spiritual Intervention Study (OASIS)51 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| H(ope)—source of hope, strength, comfort, peace |

F(aith)—beliefs | Neutral inquiry |

| O(rganized Religion)—activity in organized religion |

I(mportance)—influence of faith on life |

Inquire based on patient’s response |

| P(ersonal Spirituality)—individual spiritual activity |

C(ommunity)—religious support network |

Explore |

| E(ffects)—impact on medical and end of life issues |

A(pplication)—how faith affects medical issues |

Inquire about meaning and peace |

| Inquire about spiritual resource/support Offer referral assistance Bring inquiry to a close |

||

The HOPE survey uses an acronym to help providers with the four-step spiritual interview.50 Although the language of this survey may be more comfortable for some clinicians because it does not assume a belief system, some clinicians believe the questions are too vague, the measure is not explicitly spiritual, and therefore the outcome is not really a “spiritual assessment.” There are no validation studies for this measure, only limited, empirically validated recommendations based on the results of the interview.50 Conceptually and structurally the HOPE survey is similar to the FICA51 (Table 2). This formal framework for spiritual history taking is empirically validated against quantitative assessments of spiritual quality of life in palliative care patients.52

The OASIS project is a seven-step assessment of patient spirituality that has been evaluated for the ease of use among physicians as well as patients53 (Table 2). It is one of the few qualitative spiritual assessments empirically validated in both oncologists and patients. This format allows physicians to gain a further understanding of the patient’s religious and spiritual coping mechanisms and to provide structure to the conversation to make a timely assessment.53 Patients and physicians, even those who did not have a faith belief system, reported positive experiences with the tool.

Quantitative Spiritual Assessments and Pain

Quantitative tools also may be useful to assess patient coping in a clinical setting. Some of the most empirically validated and widely used tools include the Religious/Spiritual Coping-Long Form (RCOPE), the Religious/Spiritual Coping-Short Form (Brief RCOPE), and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-SP).

The RCOPE54 identifies the four methods of religious/spiritual coping that were described earlier in this review. Because this >100-question survey is somewhat time-consuming for patients, the Brief RCOPE,55 a 14-item version, was developed. It does not provide as much detail, but it can indicate whether a patient is using positive or negative spiritual/religious coping techniques. Negative strategies have been shown to increase medical morbidity and mortality rates. The FACIT-SP56 is a 12-item survey, validated in cross-cultural populations, that can be used to assess a patient’s spiritual well-being specifically in relation to his or her illness and quality of life.57

Research based on three of the quantitative questionnaires (RCOPE, Brief RCOPE, FACIT) indicates a strong connection between spiritual coping and patients’ pain experience.1,16 Additional evidence using the Patient Dignity Inventory shows that dignity, an important aspect of end-of-life care, and pain are strongly correlated when age is not a factor.58 Additional research using both qualitative and quantitative methods is required to better understand the association among spirituality, dignity, and pain.

Applying the Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual Framework

Palliative care providers are the clinicians who most frequently use the bio-psycho-social-spiritual framework in the assessment of pain. In the context of the palliative care consultation, whether in the inpatient or the outpatient setting, spiritual assessment by the clinician provider could be relegated easily to the lowest priority of the visit. The HOPE survey or other qualitative assessment flows more naturally within a conversation about the goals of medical care, rather than a focused consult to assess pain. Inquiry concerning a patient and a patient’s caregiver’s worldview, sources of strength, and the inherent meaning making that these lifelong patterns of thought have provided can serve several purposes for palliative care practitioners. The first goal is to support realignment of the patient in his or her accepted roles and views. Serious illness and pain, whether acute or chronic, can tear asunder a person’s sense of self and purpose. By eliciting and refocusing the patient to his or her previously trusted areas of solace, suffering can be relieved. The secondary benefit of taking the time to address the patient’s spirituality, either quantitatively or qualitatively, is that patients may believe that their provider truly has compassion for their situation and recognizes that suffering is an all-encompassing experience of their personhood. This recognition on the part of the patient that he or she is being cared for in ways that are not so clinically objective and sterile and dispassionate can truly strengthen the therapeutic relationship. Clinicians’ fears that patients will feel that either their pain is being whittled down to only an emotional experience (eg, “it’s all in your head”) or that exploring the role of their spirituality in alleviating suffering may seem too personal has not come to fruition.20

It is essential to emphasize that coming to the interview or survey questions concerning spirituality with an innate curiosity and lack of assumption is key to forming that hoped-for clinical connection. When asking patients if spirituality is important to them, a frequent answer is that they are “not a churchgoer,” artificially focusing the answer to organized religion, when the question was meant to be much broader. Spirituality and religion are sometimes incorrectly considered to be interchangeable. By initiating the questions with words such as “hope” or “connectedness” rather than “faith” or “beliefs,” patients can be assisted in taking a broader view of their spirituality and in not feeling judged by their provider.

Conclusions

In the Western biomedical model, there much focus on the biological aspects of pain management at the expense of the psychosocial or spiritual aspects of the experience.26 As a consequence, there has been a tendency to underassess and undertreat other areas that contribute to the experience of pain and related suffering. For the benefit of our patients, we need to broaden the challenge against the rigid Cartesian dualism approach to the management of pain and suffering that has ruled health care for so long and instead begin to reintegrate science with the aesthetic, the spiritual, and the philosophical aspects of humanity. By improving awareness of how to identify the multiple potential sources of pain in our patients, we have a new opportunity to alleviate some of that suffering, fulfilling the three As of multidimensional pain treatment: awareness, assessment, and alleviation.59 By integrating the resources of a multidimensional treatment team into palliative care practice, we will be able to provide a higher level of service to our patients and improve pain management at the end of life.

As palliative care experts of all disciplines increase in hospitals and other healthcare settings, evaluation of a patient’s total pain should become more common in the care of patients with pain and suffering at the end of life. With increasing focus on spirituality and meaning making in the management of pain and suffering, we expect that qualitative and quantitative research will further explore the impact of early assessment and intervention, best practices for intervention, and roles that different disciplines play in addressing and alleviating all causes of suffering.

Key Points.

At the end of life, multiple psychological, social, physical, and spiritual factors may affect the experience of pain.

Assessment of all aspects of a patient’s personhood is important in the treatment of total pain.

There are negative and positive spiritual coping mechanisms that influence a patient’s pain experience and illness trajectory.

Key qualitative and quantitative assessment tools are identified with information on how to use these tools clinically and in research.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by a grant from the UMass Memorial Cancer Center of Excellence (to AW & SM) and by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse grant K23DA030397 (to AW).

S.M. reports ongoing volunteer board membership in Compassionate Care ALS and compensation from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. J.T. has received compensation for research from the National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute, the Donaghue Foundation, Cubist Pharmaceuticals, the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, and Cambia Health Foundation.

Footnotes

The remaining authors have no financial relationships to disclose and no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Amy B. Wachholtz, Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester.

Christina E. Fitch, Division of Palliative Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester.

Suzana Makowski, Division of Palliative Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester.

Jennifer Tjia, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences and Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester.

References

- 1.Wachholtz AB, Pearce MJ, Koenig H. Exploring the relationship between spirituality, coping, and pain. J Behav Med. 2007;30:311–318. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [June 17, 2015];ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in hospice and palliative medicine (anesthesiology, family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry, or radiation oncology) https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/540_hospice_and_palliative_medicine_07012014_1-YR.pdf. Published February 7, 2015.

- 3.Lupu D, American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K. M Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic assessment of geriatric drug use via epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279:1877–1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingham JM, Foley KM. Pain and the barriers to its relief at the end of life: a lesson for improving end of life health care. Hosp J. 1998;13:89–100. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1998.11882890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Addington-Hall J, McCarthy M. Dying from cancer: results of a national population-based investigation. Palliat Med. 1995;9:295–305. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders C. A personal therapeutic journey. BMJ. 1996;313:1599–1601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark D. “Total pain,” disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958-1967. Sci Med. 1999;49:727–736. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dezutter J, Casalin S, Wachholtz A, et al. Meaning in life: an important factor for the psychological well-being of chronically ill patients? Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58:334–341. doi: 10.1037/a0034393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dezutter J, Luyckx K, Wachholtz A. Meaning in life in chronic pain patients over time: associations with pain experience and psychological well-being. J Behav Med. 2015;38:384–396. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frankl VE. Man’s Search for Meaning. Beacon Press; Boston: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, et al. The landscape of distress in the terminally ill. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson GN, Chochinov HM. Reducing the potential for suffering in older adults with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:83–93. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lysne CJ, Wachholtz AB. Pain, spirituality, and meaning making: what can we learn from the literature? Religions. 2011;2:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, et al. Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients: a 2-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1881–1885. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bush E, Rye MS, Brant CR, et al. Religious coping with chronic pain. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 1999;24:249–260. doi: 10.1023/a:1022234913899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplar ME, Wachholtz AB, O’Brien WH. The effect of religious and spiritual interventions on the biological, psychological, and spiritual outcomes of oncology patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2004;22:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pargament KI, McCarthy S, Shah P, et al. Religion and HIV: a review of the literature and clinical implications. South Med J. 2004;97:1201–1209. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146508.14898.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wachholtz AB, Pargament KI. Is spirituality a critical ingredient of meditation? Comparing the effects of spiritual meditation, secular meditation, and relaxation on spiritual, psychological, cardiac, and pain outcomes. J Behav Med. 2005;28:369–384. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wachholtz AB, Keefe FJ. What physicians should know about spirituality and chronic pain. South Med J. 2006;99:1174–1175. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000242813.97953.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wachholtz AB, Pearce MJ. Does spirituality as a coping mechanism help or hinder coping with chronic pain? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13:127–132. doi: 10.1007/s11916-009-0022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wachholtz AB, Pearce MJ. “Shaking the blues away”: energizing spiritual practices for the treatment of chronic pain. In: Plante T, editor. Contemplative Practices in Action Spirituality, Meditation, and Health. Praeger; Santa Barbara, CA: 2010. pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz GE. Testing the biopsychosocial model: the ultimate challenge facing behavioral medicine? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50:1040–1053. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.6.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. J Interprof Care. 1989;4:37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engel GL. How much longer must medicine’s science be bound by a seventeenth century world view? Psychother Psychosom. 1992;57:3–16. doi: 10.1159/000288568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melzack R. From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain. 1999;(Suppl 6):S121–S126. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–979. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eippert F, Finsterbusch J, Bingel U, et al. Direct evidence for spinal cord involvement in placebo analgesia. Science. 2009;326:404. doi: 10.1126/science.1180142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Middleton P, Pollard H. Are chronic low back pain outcomes improved with co-management of concurrent depression? Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13:8. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Covic T, Adamson B, Spencer D, et al. A biopsychosocial model of pain and depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a 12-month longitudinal study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:1287–1294. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lefebvre JC, Keefe FJ, Affleck G, et al. The relationship of arthritis self-efficacy to daily pain, daily mood, and daily pain coping in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Pain. 1999;80:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.French DJ, Holroyd KA, Pinell C, et al. Perceived self-efficacy and headache-related disability. Headache. 2000;40:647–656. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.040008647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Maixner W, et al. Self-efficacy for arthritis pain: relationship to perception of thermal laboratory pain stimuli. Arthritis Care Res. 1997;10:177–184. doi: 10.1002/art.1790100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKee DD, Chappel JN. Spirituality and medical practice. J Fam Pract. 1992;35:205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sulmasy DP. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002;42(Spec No. 3):24–33. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiech K, Farias M, Kahane G, et al. An fMRI study measuring analgesia enhanced by religion as a belief system. Pain. 2008;139:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rippentrop EA, Altmaier EM, Chen JJ, et al. The relationship between religion/spirituality and physical health, mental health, and pain in a chronic pain population. Pain. 2005;116:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borg J, Andree B, Soderstrom H, et al. The serotonin system and spiritual experiences. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1965–1969. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pargament KI. Is religion nothing but …? Explaining religion versus explaining religion away. Psychol Inquiry. 2002;13:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pargament KI, Kennell J, Hathaway W, et al. Religion and the problem solving process: three styles of coping. J Sci Study Relig. 1988;27:90–104. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips RE, Pargament KI, Lynn QK, et al. Self-directing religious coping: a deistic god, abandoning god, or no god at all? J Sci Study Relig. 2004;43:409–418. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hathaway WL, Pargament KI. Intrinsic religiousness, religious coping, and psychosocial competence: a covariance structure analysis. J Sci Study Relig. 1990;29:423–441. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hathaway W, Pargament K. The religious dimensions of coping: implications for prevention and promotion. In: Pargament KI, Maton KI, Hess RE, editors. Religion and Prevention in Mental Health: Research, Vision, and Action. Routledge; New York: 1992. pp. 129–154. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McIntosh DN, Spilka B. Religion and physical health: the role of personal faith and control. In: Lynn ML, Moberg DO, editors. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion. Vol. 2. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1990. pp. 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pargament KI, Ano G, Wachholtz AB. The religious dimension of coping: advances in theory, research, and practice. In: Paloutzian R, Park C, editors. The Handbook of the Psychology of Religion. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pargament K. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bickel C, Ciarrocchi J, Sheers N, et al. Perceived stress, religious coping styles, and depressive affect. J Psychol Christianity. 1998;17:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wachholtz AB, Pargament KI. Migraines and meditation: does spirituality matter? J Behav Med. 2008;31:351–366. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice: using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Puchalski C. Spirituality and health: the art of compassionate medicine. Hosp Physician. 2001;37:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borneman T, Ferrell B, Puchalski CM. Evaluation of the FICA Tool for Spiritual Assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kristeller JL, Rhodes M, Cripe LD, et al. Oncologist Assisted Spiritual Intervention Study (OASIS): patient acceptability and initial evidence of effects. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35:329–347. doi: 10.2190/8AE4-F01C-60M0-85C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pargament K, Smith B, Koenig H, et al. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig. 1998;37:710–724. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ando M, Morita T, Ahn S, et al. International comparison study on the primary concerns of terminally ill cancer patients in short-term life review interviews among Japanese, Koreans, and Americans. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:349–355. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, et al. The patient dignity inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:559–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wachholtz A, Makowski S. Pain versus suffering at the end of life. In: Moore R, editor. Handbook of Pain and Palliative Care: Biobehavioral Approaches for the Life Course. Springer; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]