Abstract

Background

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is the standard of care for patients with coronary heart disease (CHD). Despite considerable epidemiologic evidence that high stress is associated with worse health outcomes, stress management training (SMT) is not included routinely as a component of CR.

Methods and Results

151 outpatients with CHD aged 36 to 84 years were randomized to 12-weeks of comprehensive CR or comprehensive CR combined with SMT (CR+SMT), with assessments of stress and CHD biomarkers obtained before and after treatment. A matched sample of CR-eligible patients who did not receive CR comprised a No-CR comparison group. All participants were followed for up to 5.3 years (median = 3.2 years) for clinical events. Patients randomized to CR+SMT exhibited greater reductions in composite stress levels compared with those randomized to CR alone (P = 0.022), an effect that was driven primarily by improvements in anxiety, distress, and perceived stress. Both CR groups achieved significant, and comparable, improvements in CHD biomarkers. Participants in the CR+SMT group exhibited lower rates of clinical events compared with CR alone (18% vs. 33%, HR = 0.49 [0.25, 0.95], P = 0.035) and both CR groups had lower event rates compared to the No-CR group (47%, HR = 0.44 [0.27, 0.71], P < .001).

Conclusions

CR enhanced by SMT produced significant reductions in stress and greater improvements in medical outcomes compared with standard CR. Our findings indicate that SMT may provide incremental benefit when combined with comprehensive CR and suggest that SMT should be incorporated routinely into CR.

Clinical Trial Registration Information

www.Clinicaltrials.gov. Identifier: NCT00981253.

Keywords: stress, exercise training, coronary disease, rehabilitation, rehabilitation epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) is integral to the optimal medical care of patients with coronary heart disease (CHD).1, 2 Physical exercise, medical management of elevated blood pressure and lipids, nutritional counseling, and smoking cessation are core components of CR in this country. Although no single study has demonstrated definitively that exercise improves clinical outcomes in CHD patients, a recent meta-analysis concluded that CR reduces cardiovascular (CV) mortality and hospitalizations and improves quality of life.3

Stress management training (SMT) is not routinely included as a component of CR programs, despite mounting epidemiological evidence that elevated levels of stress are associated with greater risk of death and non-fatal cardiac events.4–6 The fact that SMT is not offered may be due to inconsistencies in the literature on the stress and CHD relationship, a lack of consensus regarding how stress is defined and measured, uncertainty about what approach is most effective, and limited support for the effectiveness of SMT in reducing stress and in improving clinical outcomes in CHD patients.7 We previously found that CHD patients with mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia receiving either SMT or exercise training had better clinical outcomes compared to usual care controls8 and that SMT and exercise each produced comparable improvements in psychological functioning as well as greater improvements in CHD biomarkers compared to usual care controls. 9 While these findings are encouraging, the added value of combining SMT with exercise training was not assessed. ‘Stand alone’ SMT interventions also may have limited real-world relevance, since such treatments are often not available in traditional disease-management programs.

The present study was designed to evaluate the potential incremental benefit of SMT when combined with comprehensive CR on a composite measure of psychological stress and CHD biomarkers of risk. In addition, we examined the impact of CR, alone and enhanced with SMT, compared to a non-randomized, matched comparison group of CR-eligible patients who elected not to participate in CR, on adverse clinical events over a follow-up period of up to 5.3 years.

METHODS

Eligibility and Trial Overview

ENHANcing Cardiac rEhabilitation with stress management training in patients with heart Disease (ENHANCED) was an efficacy trial examining the effects of SMT, when added to comprehensive CR, on self-reported stress, CHD biomarkers, and clinical outcomes. Participants underwent baseline measurement of stress, traditional CHD risk factors, and CHD biomarkers, and were randomly assigned to either comprehensive CR or comprehensive CR enhanced by SMT (CR+SMT). Participants were re-assessed at the completion of the 12-week program and were followed for clinical events for a median of 3.2 years (range 0.1 to 5.3 years). Assessors were blinded to patients’ treatment group assignment at the time of post-treatment assessments and endpoints were adjudicated without knowledge of patients’ treatment. The primary endpoint was a composite psychometric measure of stress. Secondary outcomes included CHD biomarkers and adverse cardiovascular events. A non-random sample of CR-eligible CHD patients formed a comparison group for the purpose of determining the event rates for patients with similar demographic and clinical characteristics who elected not to participate in CR.

This study was supported by grant HL093374 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the sponsor had no involvement in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript.

Participants

Outpatients with stable CHD were referred for CR by their personal physicians and underwent medical screening examinations to confirm eligibility. Indications for CR included recent acute coronary syndrome, stable angina with angiographic evidence of coronary disease, and recent coronary revascularization (coronary artery bypass graft surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention). Exclusion criteria including surgery primarily for valve replacement or repair, heart transplant, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30%, and unrevascularized left main stenosis > 50%. The protocol was approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards at Duke University and the University of North Carolina and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The first patient was randomized on April 6, 2010 and the last date for medical event adjudication was July 15, 2015.

Assessment procedures

Psychological Stress

A global ‘stress’ measure was the primary outcome, combining the following components using a mean rank constructed separately for each measure at baseline and following treatment:10

Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II)11: The 21-item BDI-II is a widely used measure of depression with scores ranging from 0 to 63, with higher scores suggesting greater depressive symptoms; scores ≥ 14 are suggestive of clinically significant depressive symptoms.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)12: The 20-item STAI was used to assess levels of state anxiety with scores ranging from 20 to 80; scores ≥ 40 suggest clinically significant anxiety in medical patients.13

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Anger14: The 8-item PROMIS Anger scale assesses several dimensions of anger with scores ranging from 8 to 40 with higher scores indicating greater anger.

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)15: The GHQ is a 12-item measure of general distress, with scores ranging from 0 to 36 and higher scores indicating greater emotional distress.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)16: The 10-item PSS assesses general distress and perceived ability to adequately cope with current life stressors with scores ranging from 0 to 40; higher scores indicate greater perceived stress.

Exercise Tolerance and Physical Activity

Exercise Treadmill Testing. Patients exercised to exhaustion or other standard endpoints under continuous electrocardiographic monitoring using a ramped Bruce protocol.17

Accelerometry. Physical activity (PA) during daily life was quantified by recording the number of steps on two successive days using the Kentz Lifecorder Plus accelerometer NL-2160 (LC; Suzuken Co. Ltd., Nagoya Japan).

Leisure-time Physical Activity. Participants completed the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire18 in which they indicated the number of times they engaged in mild, moderate, and strenuous exercise for more than 15 minutes.

Blood Lipids

Lipids were measured enzymatically from fasting blood samples (LabCorp Inc, Burlington, NC).

CHD Biomarkers of Inflammation and Autonomic function

High sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP) was quantified by ELISA. Values > 10 mg/L were truncated at 10 in order to account for acute inflammatory processes that may haveskewed the distribution of this blood marker.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and Baroreflex Sensitivity (BRS) were obtained from beat-to-beat heart rate (HR) and BP recorded from patients in the supine position using a Nexfin non-invasive BP monitor (Nexfin Model 1, BMEYE B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands).19 HRV was assessed from R-R interval changes elicited during a 100 second controlled breathing task (HRV-DB) and during five minutes of normal relaxed breathing by estimating power spectra using the Welch algorithm.20 BRS also was estimated during this five-minute resting condition using cross-spectral analysis to estimate the magnitude of the transfer function relating R-R interval oscillations to systolic BP oscillations across the 0.07 to 0.1299 Hz, or low frequency band.

Medical Endpoints

Patients documented all medical encounters annually up to five years following enrollment. Medical records were reviewed and events, categorized based on ACC/AHA criteria,21 were adjudicated by a physician assistant and a study cardiologist blinded to treatment condition. The following medical events were included: all-cause mortality, fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction, coronary or peripheral artery revascularization, stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), and unstable angina requiring hospitalization.

Interventions

Patients were randomized either to comprehensive CR-alone or CR+SMT. All patients were followed medically by their local cardiologists or primary care physicians, who were blinded to treatment condition and who managed any episodes of escalating symptoms or evidence of disease progression.

Comprehensive Cardiac Rehabilitation

Patients participated in CR at Duke University’s Center for Living (N=113) and the University of North Carolina’s Wellness Center in Chapel Hill (N=38). Comprehensive CR programs are similar throughout the state of North Carolina; patients engage in aerobic exercise three times a week for 35 minutes at a level of 70-85% of their HR reserve as determined at the time of their initial exercise treadmill test. Patients also received education about CHD, nutritional counselling based on American Heart Association guidelines, and two classes devoted to the role of stress in CHD.

SMT-enhanced Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR+SMT)

Patients in CR+SMT received the identical comprehensive CR intervention plus SMT. SMT was adapted from our previous work,8, 9 which combined education, group support, and cognitive-behavior therapy. The intervention was delivered in 12 weekly 1.5- hour sessions in groups of 4–8 participants. The SMT intervention is based upon a cognitive-behavioral model in which stress is conceptualized as an imbalance between high demands (often environmental, but also can be self-imposed) and more limited coping resources. The intervention, therefore, is directed at reducing demands and increasing coping abilities. The initial sessions are designed to establish rapport, promote group cohesion and social support, and provide a scientific basis for the importance of stress as a risk factor for adverse CV events. Strategies for reducing demands are presented including prioritizing, time management, establishing personal values, and avoidance of stress-producing situations. Subsequent sessions focus on modifying responses to situations that cannot be readily changed. Several sessions are devoted to training in progressive muscle relaxation techniques and the use of visual imagery to reduce stress. Emphasis is placed on the importance of cognitive appraisals in affecting stress responses, with recognition of irrational beliefs and cognitive distortions such as overgeneralization, catastrophizing, and all-or-nothing thinking. Later sessions focus on the importance of effective communication, including topics of assertiveness and anger management. Instruction in problem solving strategies is also provided in which participants are encouraged to apply the skills that they have learned to address everyday problems. Methods included brief lectures, group discussion, role playing, as well as instruction in specific behavioral skills, and weekly ‘homework’ assignments.

Non-Randomized, No-Cardiac Rehabilitation Comparison Group (No-CR)

To estimate the impact of CR--with and without SMT-- on clinical outcomes, we collected medical event data for comparison with individuals who were referred to CR during the same time period as the CR-alone and CR+SMT participants, but who elected not to participate. Eligible patients were stratified based on age, gender, history of MI, and date of referral. A total of 886 patients whose geographical location would have enabled them to participate in CR at Duke or UNC through CR referral records were identified from which 75 were randomly selected, within strata by research personnel blinded to patients’ medical outcome data. Patients found to have enrolled in CR elsewhere also were excluded, although participation in self-initiated physical activity or stress reduction (e.g., psychotherapy) was permitted.

Statistical analysis

Treatment effects were evaluated using general linear models adjusting for baseline through SAS 9.2 (PROC GLM, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For our primary analysis of change in ‘stress’, a pre-planned rank-based global measure of stress was created using the BDI-II, GHQ, STAI, PROMIS Anger, and PSS scores. In this approach, the global measure was created by ranking each participant on each individual ‘stress’ measure at baseline and following treatment.10 A mean rank score was created by averaging across all ‘stress’ measures at pre-treatment and at post-treatment. Treatment effects were analyzed following the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, with post-treatment missing data (< 5%) managed using multiple imputation methods available in SAS (PROC MI). We first examined changes in our global ‘stress’ outcome and, if significant, explored changes in individual components of the stress composite in a secondary, explanatory step.22 Our primary interest is not so much to identify which component is important, but rather to assess the effectiveness of treatment on a single, global measure of stress based on the elements comprising the ‘stress’ construct. We did not correct for multiple components because, as noted by Tandon,23 the Bonferroni correction fails to make efficient use of the collective data, especially when one expects several measures (e.g., stress, anger, depression, anxiety) to behave similarly and there is no a priori reason to believe that one of these measures would be more significant than another. Analyses of treatment changes in CHD biomarkers, lipids, and aerobic fitness / physical activity were conducted using the post-treatment value as the outcome variable, controlling for the respective pre-treatment level, with group assignment as the predictor of interest. In these analyses, a Bonferonni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons separately within each outcome domain (i.e., CHD biomarkers, lipids, and aerobic fitness/physical activity).

For analysis of clinical events, we evaluated the effects of treatment using Cox proportional hazards model (PROC PHREG), with dummy coding constructed to compare the CR, CR+SMT, and No-CR groups. In order to account for potential treatment differences in important medical predictors of clinical events, we controlled for age, heart failure, and treatment site in our models. Within our analyses of clinical event models the first event following randomization was coded as the event and those participants with no events or who dropped out were censored at the time of last contact. We also examined the impact of treatment on clinical events among CR+SMT and CR-alone participants compared to the No-CR group. We evaluated the extent to which models met assumptions, including additivity, linearity, proportional hazards, and distribution of residuals. A priori power estimates suggested that we would have 80% power to detect a 0.47-SD difference in the stress composite between the CR+SMT and CR-alone groups.

RESULTS

Participant Flow

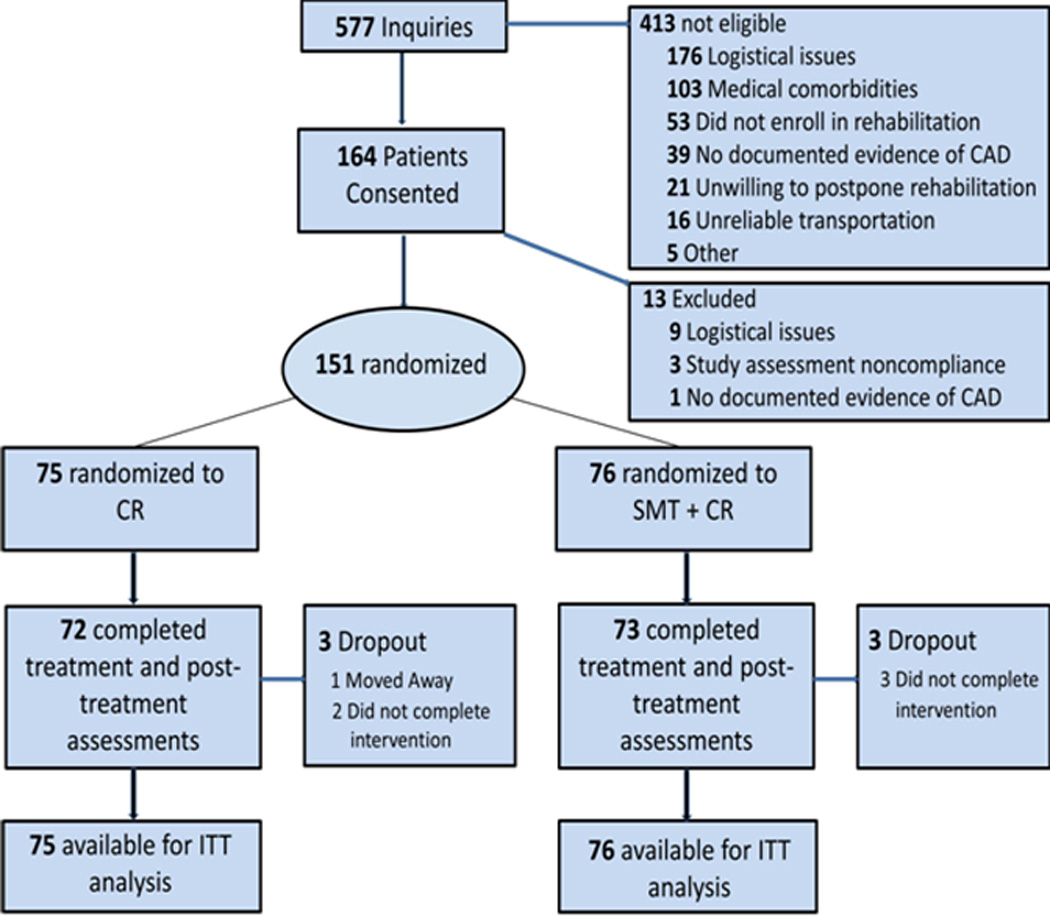

Figure 1 displays the flow of participants during the trial. Of the 577 individuals who were considered for CR, 164 met initial inclusion criteria and 151 were randomized: 75 to comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation (CR) and 76 to comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation plus SMT (CR+SMT).

Figure 1.

Participant flow in the ENHANCED (Enhancing Standard Cardiac Rehabilitation with Stress Management Training in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease) clinical trial. CR = Cardiac Rehabilitation; CR+SMT = Cardiac Rehabilitation Enhanced with Stress Management Training; ITT = intention-to-treat.

Medical outcome data also were obtained for 75 individuals who were referred to CR but, for a variety of reasons (e.g., inconvenient, too busy, preferred to exercise on their own, not interested, etc.), elected not to participate in CR (No-CR).

Participant Characteristics

Demographic, background, and medical characteristics of the CR groups and No-CR patients are shown in Table 1. The treatment groups were similar on background clinical and demographic characteristics and also were similar to the No-CR comparison group.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the ENHANCED sample.

| Variable | CR + SMT (n = 76) |

CR (n = 75) |

No-CR (n = 75) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Background and Demographics (n [%]) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) y | 61.8 (10.8) | 60.4 (10.6) | 60.9 (9.1) |

| Female | 31 (41%) | 24 (32%) | 28 (37%) |

| White | 58 (76%) | 51 (68%) | 50 (67%) |

| Married or Co-habitating | 50 (66%) | 49 (65%) | 41 (55%) |

| Employed Full-time | 29 (38%) | 28 (37%) | 34 (45%) |

| Current or Former Smoker | 38 (50%) | 41 (55%) | 49 (65%) |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD) kg / m2 | 30.2 (5.9) | 30.8 (5.2) | 30.3 (5.8) |

|

Medical History (n [%]) | |||

| Hypertension | 58 (76%) | 60 (80%) | 58 (77%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 61 (80%) | 57 (76%) | 64 (85%) |

| Diabetes | 25 (33%) | 31 (41%) | 28 (37%) |

| Myocardial Infarction History† | 38 (50%) | 43 (57%) | 41 (55%) |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Graft History† | 21 (28%) | 17 (23%) | 22 (29%) |

| Heart Failure | 5 (7%) | 3 (4%) | 5 (7%) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 2 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (4%) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.1) |

| LVEF, mean (SD) % | 55.1 (9.6) | 54.3 (7.4) | 54.3 (7.0) |

| Indication for Cardiac Rehabilitation | |||

| Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) | 19 (25%) | 10 (13%) | 19 (25%) |

| Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI)* | 29 (38%) | 23 (31%) | 11 (15%) |

| Myocardial Infarction | 3 (4%) | 8 (11%) | 11 (15%) |

| Myocardial Infarction + CABG | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (5%) |

| Myocardial Infarction + PCI | 20 (37%) | 26 (35%) | 20 (27%) |

| Angina | 3 (4%) | 6 (8%) | 10 (13%) |

| ACE-Inhibitor or Angiotensin Receptor Blocker | 47 (62%) | 55 (73%) | 46 (61%) |

| Beta Blocker | 66 (87%) | 67 (89%) | 66 (88%) |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 10 (13%) | 17 (23%) | 13 (17%) |

| Diuretic | 22 (29%) | 23 (31%) | 24 (32%) |

| Other Blood Pressure Medication | 2 (3%) | 5 (7%) | 2 (3%) |

| Diabetes Medication | 22 (29%) | 25 (33%) | 32 (43%) |

| Nitrates | 42 (55%) | 43 (57%) | 43 (57%) |

| Aspirin | 72 (95 %) | 72 (96 %) | 73 (97 %) |

| Other Anti-Platelet Medication | 56 (74%) | 53 (71%) | 45 (60%) |

| Psychotropic Medication | 26 (34%) | 26 (35%) | 24 (32%) |

| Statin | 66 (87%) | 66 (88%) | 65 (87%) |

|

Lipids and Blood Pressure (mean, [SD]) | |||

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 175.4 (46.4) | 161.7 (42.0) | ------------------- |

| LDL Cholesterol mg/dL* | 109.6 (42.5) | 94.1 (40.6) | ------------------- |

| HDL Cholesterol, mg/dL | 40.5 (11.9) | 41.6 (11.9) | ------------------- |

| Serum Triglycerides, mg/dL | 132.8 (74.4) | 150.1 (88.4) | ------------------- |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 113.5 (15.0) | 116.6 (16.7) | ------------------- |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 61.9 (7.6) | 62.9 (9.0) | ------------------- |

|

Aerobic Fitness and Physical Activity (mean [SD]) | |||

| Exercise Treadmill Test Duration (min) | 7.7 (2.5) | 7.3 (2.4) | ------------------- |

| Metabolic Equivalents (METs) | 8.6 (2.4) | 8.2 (2.6) | ------------------- |

| Accelerometry Steps | 10,774 (5783) | 10,840 (6312) | ------------------- |

| Accelerometry Light Activity (min) | 29.9 (14.1) | 31.5 (16.8) | ------------------- |

| Accelerometry Moderate Activity (min) | 91.6 (53.2) | 91.5 (59.1) | ------------------- |

| Accelerometry Total Activity (min) | 121.7 (63.1) | 123.4 (70.1) | ------------------- |

| Leisure-Time Physical Activity (min) | 22.4 (19.7) | 18.5 (22.5) | ------------------- |

|

Coronary Heart Disease Biomarkers (mean [SD]) | |||

| HRV-DB (msec) | 149 (118) | 171 (123) | ------------------- |

| Low Frequency HRV (ln msec2) | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.4) | ------------------- |

| High Frequency HRV (ln msec2) | 4.9 (0.9) | 5.2 (1.2) | ------------------- |

| Baroreflex Sensitivity (msec/mmHg) | 6.1 (3.7) | 7.0 (5.1) | ------------------- |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 2.6 (3.1) | 2.7 (2.8) | ------------------- |

|

Composite Stress Measures (mean [SD]) | |||

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | 8.1 (7.7) | 9.0 (9.0) | ------------------- |

| Spielberger Anxiety Inventory-State | 35.1 (11.8) | 36.3 (11.8) | ------------------- |

| PROMIS Anger | 16.1 (5.5) | 16.2 (6.1) | ------------------- |

| General Health Questionnaire | 12.6 (5.9) | 12.3 (6.0) | ------------------- |

| Perceived Stress | 15.3 (8.2) | 15.4 (7.9) | ------------------- |

P < .05 for treatment group differences; SD = standard deviation; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LDL = Low Density Lipoprotein; HDL = High Density Lipoprotein; HRV = Heart Rate Variability; HRV-DB = Heart Rate Variability during Deep Breathing; hsCRP = high sensitivity C-Reactive Protein; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Includes previous medical history for event as well as current indication for referral to cardiac rehabilitation (i.e., recent event)

Treatment Adherence

Exercise attendance was similar for both CR groups. Participants in CR-alone and CR+SMT each completed a mean of 33 out of a possible 36 exercise sessions (92% attendance). Attendance at SMT classes was excellent, with participants attending a median of 11 out of 12 sessions. Six participants (4%) did not complete the treatment protocol: 3 from CR and 3 from CR+SMT.

We used a modified version of the Morisky Adherence Scale 24 to assess medication adherence before and following the 12-week CR program with scores ranging from 0 to 7. Participants in CR-alone and CR+SMT were very adherent upon study entry: 95% indicated that they never or rarely missed taking their heart medications. Adherence was maintained over the 12 weeks and there was no difference in adherence between the two groups following treatment (CR+SMT = 0.30, CR-alone = 0.36; P = 0.52).

Effects of Treatment on Stress

Time and treatment changes for the stress measures are presented in Table 2, adjusted for the pretreatment level of each outcome. Both CR groups showed reductions on each stress component following treatment (P’s ≤ .001). A treatment group main effect was observed for the global Stress score in which the CR+SMT group showed greater reductions compared to CR-alone (P = 0.022). In secondary, explanatory analyses, we found that the CR+SMT group showed greater improvements in anxiety (STAI; P = 0.025) and distress (GHQ; P = 0.049), and tended to show greater reductions in perceived stress (PSS; P = 0.063) compared with CR-alone. We note that univariate analyses of the stress components were not corrected, and serve as a guide to interpretation of the global test results. Of note, 34 individuals exhibited clinically elevated levels of depression prior to treatment (i.e., BDI-II ≥ 14) and 48 individuals reported clinically significant levels of anxiety (STAI ≥ 40). In supplementary analyses among this depressed subgroup, individuals in the CR+SMT group exhibited 14.0-point reduction (9.2, 18.8) on the BDI-II, compared with reductions of 7.8 (2.7, 12.9) points in the CR group (P = 0.07). Individuals with high anxiety in CR + SMT reported a 14.2-point reduction (9.6, 18.8) compared to a 9.8 (5.4, 14.2) reduction in CR alone (P = 0.18).

Table 2.

Treatment effects on composite stress measures after adjustment for the pretreatment level of each outcome. Values are represent change scores (T2 – T1) and are presented as mean change (95% confidence interval). Effect sizes are presented using Cohen’s d. P-values are not adjusted for multiple testing.

| Variable | CR+SMT (n = 76) |

CR (n = 75) |

Cohen’s d |

Time Effect |

CR+SMT vs. CR Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck Depression Inventory-II |

−3.5 (−5.0, −2.1) | −2.6 (−4.1, −1.2) | 0.15 | <0.001 | P = 0.37 |

| Spielberger Anxiety Inventory-State |

−5.6 (−7.4, −3.7) | −2.6 (−4.5, −0.7) | 0.37 | <0.001 | P = 0.025 |

| General Health Questionnaire |

−4.8 (−5.8, −3.7) | −3.3 (−4.4, −2.2) | 0.33 | <0.001 | P = 0.049 |

| PROMIS Anger Questionnaire |

−2.0 (−3.0, −1.0) | −1.0 (−2.1, 0.0) | 0.22 | 0.001 | P = 0.16 |

| Perceived Stress Scale | −4.2 (−5.4, −3.0) | −2.6 (−3.9, −1.3) | 0.30 | <0.001 | P = 0.063 |

CHD Biomarkers, Lipids, and Exercise Capacity/Physical Activity

CR, alone and combined with SMT, was associated with significant improvements in CHD biomarkers, lipids, exercise capacity and physical activity during daily life. However, there were no treatment group differences on any of the measures (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment effects on CHD biomarkers, lipids, and physical activity after adjustment for the pretreatment level of each outcome. Values are presented as mean change scores from baseline (95% confidence intervals). P-values are adjusted for multiplicity within each domain using a Bonferonni correction.

| Variable | CR + SMT (n = 76) |

CR (n = 75) |

Time Effect |

CR + SMT vs. CR Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | ||||

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | −22.9 (−31.9, −14.0) | −20.0 (−29.7, −10.2) | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| LDL Cholesterol, mg/dL | −24.2 (−31.7, −16.8) | −22.4 (−30.5, −14.3) | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| HDL Cholesterol, mg/dL | 3.0 (1.2, 4.7) | 2.7 (0.7, 4.6) | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | −7.4 (−21.2, 6.4) | −11.2 (−26.6, 4.2) | 0.22 | 0.99 |

| CHD Biomarkers | ||||

| hsCRP, mg/L | −0.9 (−1.4, −0.5) | −0.4 (−0.9, 0.0) | <0.01 | 0.95 |

| HRV-DB (msec) | 13.1 (−8.0, 34.3) | 26.0 (5.5, 46.5) | 0.055 | 0.99 |

| Low Frequency HRV, log-transformed | 0.17 (−0.08, 0.41) | 0.28 (0.04, 0.51) | 0.075 | 0.99 |

| High Frequency HRV, log-transformed | 0.08 (−0.11, 0.27) | 0.22 (0.03, 0.41) | 0.17 | 0.99 |

| Baroreflex Sensitivity, msec/mm Hg | 0.47 (−0.39, 1.33) | 0.93 (0.09, 1.77) | 0.21 | 0.99 |

| Aerobic Fitness and Physical Activity | ||||

| Leisure-time Physical Activity | 20.6 (15.6, 25.5) | 15.9 (10.8, 21.0) | <0.01 | 0.67 |

| Exercise Treadmill Duration, min | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.9) | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| Exercise Treadmill Metabolic Equivalents (METs) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.8) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| Accelerometry Total Steps | 1412 (213, 2610) | 687 (−520, 1893) | 0.092 | 0.99 |

Note: HDL = high density lipoprotein; HRV = heart rate variability; hsCRP = high sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL = low density lipoprotein.

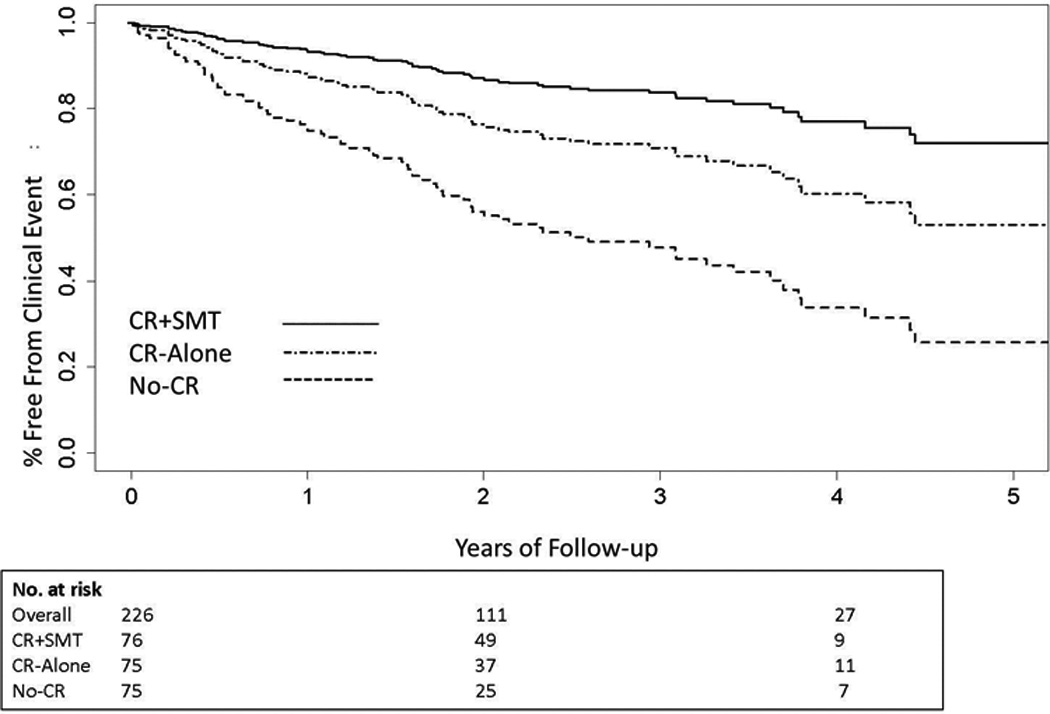

Comparison of Clinical Events in CR-alone and CR+SMT

Thirty-nine participants (26%) experienced a clinical event over a follow up period of up to 5.3 years (median 3.2.; [IQR=1.9] years; Table 4). Time-to-event models demonstrated that participants randomized to CR+SMT experienced a lower event rate (18%) compared with individuals randomized to CR (33%; HR = 0.47 [0.24, 0.91], P = 0.03). The estimated optimism for model fit was modest (17%), suggesting minimal bias from overfitting.

Table 4.

Clinical events for CR+SMT, CR-alone, and No-CR groups.

| Group | Total Events | Death | MI | Stent / CABG |

Stroke/TIA | Peripheral Revascularization |

Angina Requiring Hospitalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR+SMT (n = 76) | 14 (18%) | 0 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| CR-alone (n = 75) | 25 (33%) | 2 | 6 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| No-CR (n = 75) | 35 (47%) | 4 | 9 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

CR-alone = cardiac rehabilitation alone; CR+SMT = cardiac rehabilitation enhanced with stress management training; No-CR = non-randomized comparison group who did not participate in cardiac rehabilitation; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; MI = myocardial infarction; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Comparison of Clinical Events in CR Groups and Matched No-CR Controls

In order to assess the impact of CR on medical outcomes, we compared patients randomized to CR-alone and CR+SMT to a randomly selected sample of patients referred to CR but who elected not to participate; the comparison group was matched on age, indication for referral to CR, and time of referral. The follow-up interval was identical for CR and no-CR controls. We observed 35 clinical events in the No-CR group (47%), compared to 39 in the CR groups (26%; HR = 0.35 [0.22, 0.56], P < .001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative time-to-event curves for clinical events in the CR+SMT, CR-alone, and No-CR groups. Clinical events included all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, cardiac or peripheral vascular intervention, stroke/TIA, or unstable angina requiring hospitalization. Participants in the CR+SMT were at significantly lower risk of clinical events compared with the CR-alone group (HR= 0.47 [0.24, 0.91], P = 0.025). Both CR groups had lower event rates compared with a non-randomized, matched No-CR control group (HR = 0.35 [0.22, 0.56], P < .001). Number at risk represents participants with follow-up data for clinical events who had not yet had an event at years 0, 2, and 4.

Mediators of CR and Medical Events

We also examined whether reductions in stress levels mediated the relationship of CR on clinical events. Greater reductions in stress were associated with a lower rate of clinical events (HR = 0.58 [0.34, 0.99], P = 0.048). Controlling for reductions in stress attenuated the relationship between treatment group and clinical events (HR = 0.59 [0.31, 1.14], P = 0.11), while the relationship between stress and clinical events became marginally significant (HR = 0.60 [0.35, 1.02], P = 0.059), suggesting that reduced stress partially mediated the effects of treatment group on clinical outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Although there is substantial epidemiologic evidence that high levels of stress are associated with worse medical outcomes,4–6 there is considerably less evidence that interventions designed to reduce stress improve those outcomes.25 In the present trial, stress management, when added to comprehensive CR, resulted in greater reductions in patient-reported stress compared to CR alone. Furthermore, reductions in stress were associated with reduced risk of adverse clinical events, with almost a 50% reduction in clinical events compared to CR without SMT.

Participants in both CR and CR+SMT achieved improvements in blood lipids, heart rate variability, inflammation, exercise tolerance and self-reported leisure time physical activity. In a secondary analysis, we also noted that CR was associated with better clinical outcomes relative to a No-CR comparison group. The overall event rates were higher for patients who elected not to engage in CR compared to CR alone or CR+SMT. These findings contrast with results from the recent RAMIT study,26 which found that comprehensive CR had no effect on mortality, cardiac or psychological morbidity, and concluded that the evidence for the value of CR was “weak.” Important differences in how CR is practiced in England and the United States may explain the discrepant results. In the British study, CR was performed weekly for only 6–10 weeks, while in the US, CR is more intensive. In the ENHANCED trial, patients engaged in exercise three times per week for 12 weeks, and participated in nutrition and stress classes; patients randomized to the CR+SMT group also received an additional 1.5 hrs per week of group SMT. While patients in CR+SMT reported reduced symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress, the stress reduction program for the RAMIT trial did not reduce patients’ stress levels, which could account for the differences in clinical outcomes.

Several other large RCTs reported no benefit of SMT compared to usual care controls in reducing stress and improving clinical outcomes. Jones and West27 randomized 2,328 post-MI patients to 7 weekly sessions of SMT or usual care and followed them for 12 months. After six months, the prevalence rates of clinical anxiety and depression remained high and there were no group differences in levels of anxiety or depression following treatment. Moreover, there was no difference between the groups in the incidence of MI, cerebrovascular accident, heart failure, or revascularizations. Frasure-Smith and colleagues28 randomized 1,376 post-MI patients to a stress management intervention delivered over the telephone or to usual care. Following treatment, there were no group differences in anxiety or depression and there also was no difference in clinical outcomes. The ENRICHD trial 29 examined the benefits of a cognitive-behavioral intervention in 2400 post-MI patients who were depressed or who reported low social support. Results showed a modest, 2-point difference in BDI scores in the intervention group compared to usual care, and there were no differences in the combined endpoint of all-cause mortality and non-fatal reinfarction. These aforementioned studies also provided SMT as a sole intervention, without exercise or other elements of comprehensive CR. Thus, not all interventions designed to reduce stress are successful, and the failure to reduce stress may provide one explanation for the failure to observe improved medical outcomes.

The ENHANCED trial provided SMT to all patients randomized to the CR+SMT intervention, regardless of their baseline levels of stress and did not specifically target patients in acute distress or with significant psychopathology. Few RCTs include only patients meeting a clinical threshold for psychological symptoms or psychiatric pathology, and in studies with and without patients with diagnosed psychopathology the results are often not reported separately.30 Some meta analyses suggest that patients with greater psychopathology at baseline show smaller reductions in depression with treatment compared with patients with less psychopathology.30 We found that patients with greater stress tended to exhibit larger improvements. For example, depressive symptoms were reduced in both CR and CR+SMT groups, which is not surprising given that depressive symptoms are reduced by CR,31 and that exercise has been shown to reduce depressive symptoms in patients with major depression,32 stable CHD33 and heart failure.34 Although failing to achieve statistical significance, it is noteworthy that in our subset of patients with elevated depressive symptoms upon study entry, the addition of SMT to CR appeared to be especially beneficial. The CR+SMT group exhibited a 14-point reduction in BDI-II scores compared to an 8-point reduction with CR alone. A 6-point difference is considered clinically meaningful and is greater than the 2- to 3-point differences observed in placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant medications35–37 and in trials of psychotherapy in CHD patients.29

Limitations

Our sample was small and we observed few ‘hard’ endpoints (e.g., death and non-fatal MI). A larger sample would provide greater power to detect treatment group differences in specific stress components. Although the effect sizes were relatively modest, because comprehensive CR alone has been shown to produce significant improvements in quality of life,3 the incremental benefit of SMT to standard CR should not be underestimated In addition, analysis of clinical events offered promising evidence for the value of CR+SMT in improving clinical outcomes, which will need to be confirmed in larger trials. CR participants had better clinical outcomes compared to patients who elected not to engage in CR. Patients in the no-CR comparison group were matched on age, gender, and history of MI, did not differ on any measured clinical or demographic characteristic, and continued to exhibit significantly higher rates of clinical events in sensitivity analyses adjusted for age, gender, ejection fraction, and medical comorbidities. However, it is possible that patients in the non-random comparison group may have differed from the CR participants in ways that we did not measure, which may have contributed to their higher rates of clinical events. We used a global measure of stress, combining scores from multiple instruments. Because there is no universally accepted single measure of stress, we selected well-validated instruments based upon epidemiologic evidence that distress,15, 38 depression,39–43 anxiety,44–46 and anger 47, 48 -- generally subsumed under the term “stress”-- are associated with increased risk for adverse outcomes in CHD patients. Composite measures of stress have been used in other studies,6 but there is still no ‘gold standard’ for measuring stress and our global measure combines scores from well-validated instruments, each with excellent psychometric properties. Adherence to the program was excellent with few dropouts. Research volunteers may have been especially motivated to participate in the program, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusion

Patients randomized to CR enhanced by stress management had greater reductions in stress and had better clinical outcomes compared to those patients randomized to CR alone. In the same way that exercise training does not target only those patients with low levels of physical fitness, the present findings indicate that SMT could be beneficial for all cardiac patients and suggest that SMT should be incorporated into comprehensive CR. A multi-site effectiveness trial will be needed to confirm the applicability of these findings to the larger CR population.

Clinical Perspectives.

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) represents the standard of care for patients with coronary heart disease (CHD). Despite considerable epidemiologic evidence that high levels of stress are associated with worse prognosis, there is limited evidence that reducing stress improves clinical outcomes. ENHANCED was a randomized clinical trial in which patients referred to CR completed a psychometric ‘stress’ battery and underwent evaluation of CHD biomarkers including measures of endothelial dysfunction, heart rate variability, baroreflex sensitivity, and inflammation before and after a 12-week treatment program of comprehensive CR alone (N= 75) or comprehensive CR enhanced by stress management training (SMT)(N=76). SMT consisted of 12 weekly, 1.5 hour sessions that provided education, group support, and instruction in methods for coping more effectively with stress (e.g., time management, progressive muscle relaxation training, cognitive restructuring, communication skills). A non-random sample of CR-eligible patients who declined to engage in CR formed a no-CR comparison group. Results showed that while both CR groups reported less stress, CR enhanced by SMT achieved greater reductions in stress compared to CR-alone. Compared to the matched no-CR comparison group, both CR groups had fewer clinical events (all-cause mortality, fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction, coronary or peripheral artery revascularization, stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), and unstable angina requiring hospitalization). Moreover, combining stress management training with CR (i.e., CR+SMT) resulted in better clinical outcomes compared to CR-alone. These findings confirm the value of CR in reducing the risk for adverse clinical events. Furthermore, SMT provided incremental value to standard CR by further reducing stress and improving clinical outcomes. Including SMT as a routine component of standard CR, regardless of patients’ reported levels of stress, should be encouraged.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our thanks and gratitude to the members of our Data and Safety Monitoring Board: Nanette Wenger MD (chair), Mark Appelbaum PhD, and Nancy Houston Miller RN for their guidance and support of this study. Thanks also are extended to Michael Babyak, PhD for his statistical advice, and to our research staff including Jenny Wang, PhD, Rachel Funk BA, Sarah Newman MA, Maureen Hayes BA, Payton Kendsersky BA, Michael Ellis, Catherine Wu MS, Heidi Scronce BS, Lauren Williamson BS, and Monika Grochulski BS. We also want to thank the staff at the respective exercise sites -- Karen Craig (Duke), Elizabeth Mattheson (UNC), and Alycia Hassett, MD (Duke Regional Hospital) -- for their support.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Balady GJ, Williams MA, Ades PA, Bittner V, Comoss P, Foody JA, Franklin B, Sanderson B, Southard D. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update: A scientific statement from the american heart association exercise, cardiac rehabilitation, and prevention committee, the council on clinical cardiology; the councils on cardiovascular nursing, epidemiology and prevention, and nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism; and the american association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation. Circulation. 2007;115:2675–2682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.180945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ades PA. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:892–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra001529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, Zwisler A-D, Rees K, Martin N, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart diseasecochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, Saab PG, Kubzansky L. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: The emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:637–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the interheart study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Sliwa K, Zubaid M, Almahmeed WA, Blackett KN, Sitthi-amorn C, Sato H, Yusuf S. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from 52 countries (the interheart study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:953–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rees K, Bennett P, West R, Davey SG, Ebrahim S. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD002902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal JA, Jiang W, Babyak MA, Krantz DS, Frid DJ, Coleman RE, Waugh R, Hanson M, Appelbaum M, O'Connor C, Morris JJ. Stress management and exercise training in cardiac patients with myocardial ischemia. Effects on prognosis and evaluation of mechanisms. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2213–2223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumenthal JA, Sherwood A, Babyak MA, Watkins LL, Waugh R, Georgiades A, Bacon SL, Hayano J, Coleman RE, Hinderliter A. Effects of exercise and stress management training on markers of cardiovascular risk in patients with ischemic heart disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1626–1634. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien PC. Procedures for comparing samples with multiple endpoints. Biometrics. 1984;40:1079–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spielberger CE, Gorsuch RL. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunevicius A, Staniute M, Brozaitiene J, Pop VJM, Neverauskas J, Bunevicius R. Screening for anxiety disorders in patients with coronary artery disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, Amtmann D, Bode R, Buysse D, Choi S, Cook K, Devellis R, DeWalt D, Fries JF, Gershon R, Hahn EA, Lai J-S, Pilkonis P, Revicki D, Rose M, Weinfurt K, Hays R, Group PC. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (promis) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frasure-Smith N. In-hospital symptoms of psychological stress as predictors of long-term outcome after acute myocardial infarction in men. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90432-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaminsky LA, Whaley MH. Evaluation of a new standardized ramp protocol: The bsu/bruce ramp protocol. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1998;18:438–444. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199811000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ameloot K, Van De Vijver K, Van Regenmortel N, De Laet I, Schoonheydt K, Dits H, Broch O, Bein B, Malbrain ML. Validation study of nexfin(r) continuous non-invasive blood pressure monitoring in critically ill adult patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:1294–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch PD. The use of fast fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short modified periodograms. IEEE Trans Audio Electroacoust. 1967;15:70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, Chaitman BR, Cutlip DE, Farb A, Fonarow GC, Jacobs JP, Jaff MR, Lichtman JH, Limacher MC, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, Nissen SE, Smith EE, Targum SL. 2014 acc/aha key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trialsa report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical data standards (writing committee to develop cardiovascular endpoints data standards) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:403–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.018. Epub 2014 Dec 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tilley BC, Marler J, Geller NL, Lu M, Legler J, Brott T, Lyden P, Grotta J. Use of a global test for multiple outcomes in stroke trials with application to the national institute of neurological disorders and stroke t-pa stroke trial. Stroke. 1996;27:2136–2142. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.11.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tandon PK. Applications of global statistics in analysing quality of life data. Stat Med. 1990;9:819–827. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Relman AS, Angell M. Resolved: Psychosocial interventions can improve clinical outcomes in organic disease (con) Psychosom Med. 2002;64:558–563. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000023411.02546.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West RR, Jones DA, Henderson AH. Rehabilitation after myocardial infarction trial (ramit): Multi-centre randomised controlled trial of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation in patients following acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2012;98:637–644. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones DA, West RR. Psychological rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: Multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;313:1517–1521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7071.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Prince RH, Verrier P, Garber RA, Juneau M, Wolfson C, Bourassa MG. Randomised trial of home-based psychosocial nursing intervention for patients recovering from myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1997;350:473–479. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ, Czajkowski SM, DeBusk R, Hosking J, Jaffe A, Kaufmann PG, Mitchell P, Norman J, Powell LH, Raczynski JM, Schneiderman N. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: The enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease patients (enrichd) randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whalley B, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21:109–121. doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on depression and its associated mortality. Am J Med. 2007;120:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mead GE, Morley W, Campbell P, Greig CA, McMurdo M, Lawlor DA. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Adverse psychological and coronary risk profiles in young patients with coronary artery disease and benefits of formal cardiac rehabilitation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1878–1883. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, O’Connor C, Keteyian S, Landzberg J, Howlett J, Kraus W, Gottlieb S, Blackburn G, Swank A, Whellan DJ. Effects of exercise training on depressive symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure: the HF-ACTION randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308(5):465–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang W, Velazquez EJ, Kuchibhatla M, Samad Z, Boyle SH, Kuhn C, Becker RC, Ortel TL, Williams RB, Rogers JG, O'Connor C. Effect of escitalopram on mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia: Results of the remit trial. JAMA. 2013;309:2139–2149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glassman AH, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT, Jr, Krishnan KR, van Zyl LT, Swenson JR, Finkel MS, Landau C, Shapiro PA, Pepine CJ, Mardekian J, Harrison WM, Barton D, McLvor M Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial G. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute mi or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Silva SG, Cuffe MS, Callwood DD, Zakhary B, Stough WG, Arias RM, Rivelli SK, Krishnan R. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure: Results of the sadhart-chf (sertraline against depression and heart disease in chronic heart failure) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dimsdale JE. Psychological stress and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1237–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction. Impact on 6-month survival. JAMA. 1993;270:1819–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Juneau M, Theroux P. Depression and 1-year prognosis in unstable angina. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1354–1360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:1049–1053. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Doering LV, Frasure-Smith N, Freedland KE, Jaffe AS, Leifheit-Limson EC, Sheps DS, Vaccarino V, Wulsin L American Heart Association Statistics Committee of the Council on E, Prevention, the Council on C, Stroke N. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: Systematic review and recommendations: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2014;129:1350–1369. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martens EJ, de Jonge P, Na B, Cohen BE, Lett H, Whooley MA. Scared to death? Generalized anxiety disorder and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease:The heart and soul study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:750–758. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothenbacher D, Hahmann H, Wusten B, Koenig W, Brenner H. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with stable coronary heart disease: Prognostic value and consideration of pathogenetic links. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:547–554. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280142a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watkins LL, Koch GG, Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson JR, O'Connor C, Sketch MH. Association of anxiety and depression with all-cause mortality in individuals with coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000068. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams RB, Haney TL, Lee KL, Kong Y, Blumenthal JA, Whalen RE. Type a behavior, hostility and coronary atherosclerosis. Psychosom Med. 1980;42:539–545. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Mulry RP, Tofler GH, Jacobs SC, Friedman R, Benson H, Muller JE. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction onset by episodes of anger. Circulation. 1995;92:1720–1725. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]