Abstract

During the intracellular process of macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy), a membrane-bound organelle, the autophagosome, is generated de novo. The remodeling of the autophagic membrane during the life cycle of the organelle is a complex multistep process and involves several changes in the topology of the autophagic membrane. Here, we focus on the final step of autophagosome formation, the closure of the phagophore, during which the inner and outer autophagic membranes become separate entities. We argue that this topological membrane transformation is a membrane scission event. Surprisingly, not a single recent review describes this substep as membrane scission (or membrane fission). In contrast, a number of publications imply that membrane fusion is involved. We discuss the potential sources for misinterpretation and recommend to consistent use of the unambiguous term “membrane scission.”

Keywords: autophagy, closure, membrane fission, membrane fusion, membrane neck, membrane scission, nuclear pore, phagophore, sporulation, yeast

Autophagy is a basic, catabolic pathway in eukaryotic cells. In a multistep process, a new organelle is developed: the autophagosome. The formation of autophagosomes involves a large number of both essential and accessory proteins that act to remodel the autophagic membrane in an intricate manner.1 Even though our understanding of autophagy has significantly improved during the last decade, several steps of the autophagic pathway remain ill defined and not well understood. In order to facilitate further progress in this research area, it is important to use an appropriate terminology for the various substeps of the process and to avoid unclear or incorrect terminology that can easily lead to confusion,2 especially for young scientists and new researchers in the field.

In this comment, we focus on membrane remodeling during autophagy. In general, such remodeling processes can be described as a combination of changes in membrane morphology and topology.3,4 Morphological transformations arise from continuous and smooth changes of the membrane curvature and shape, whereas topological transformations of the membrane involve intermediate states in which the membranes have to deviate strongly from their usual bilayer structure. Two topological transformations are ubiquitous: membrane fusion and membrane scission (or membrane fission).

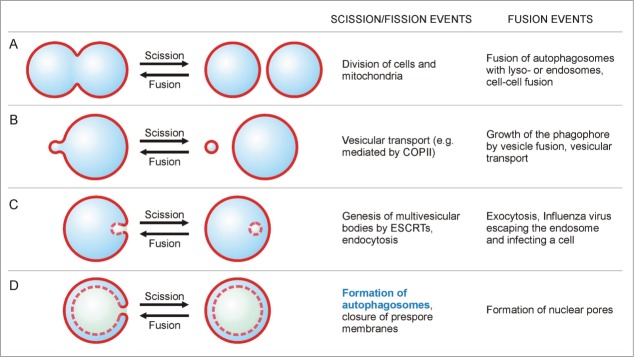

In Figure 1, we illustrate and compare the processes of membrane fusion and membrane scission. Both events change the topology of the membrane in opposite directions: Fusion generally refers to the process where 2 separate bilayers merge and form a single continuous bilayer, whereas scission refers to the reverse topological change that is the dissection or split-up of one membrane into 2 separate ones. For the split-up of membranes, 2 terms are commonly used: “scission” and “fission.” None of the latter terms seems to be exclusively used for specific topological transformations; however, “fission” typically refers to processes generating 2 spatially separate aqueous compartments that are not nested into one another, as e.g. in the division of mitochondria (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Membrane scission and membrane fusion. (A) Membrane scission (or fission) is illustrated for the case where 2 equally sized bilayers are formed from one bilayer. Fusion is the topologically reverse process, where 2 bilayers or vesicles merge into a single one. (B, C) The size and location of the 2 vesicles relative to each other are not relevant to identify a process as scission or fusion. (D) Membrane scission and fusion of 2 almost equally sized vesicles, stacked within each other. The formation of the autophagosome from the cup-shaped phagophore provides an example for a scission process. Each bilayer is depicted as a single line, solid lines represent directly “visible” bilayers and dashed lines correspond to bilayers evident in cross sections only.

Membrane fusion and membrane fission or scission necessarily involve nonbilayer states of the membrane molecules, but the corresponding pathways of molecular remodeling are variable and can involve a variety of transition states as explicitly shown for membrane fusion.5 For both fusion and fission processes, the size of the membranes (organelles/vesicles) and their locations relative to each other are not relevant for identifying the process as fusion or fission, as shown by the examples of vesicular transport, or endo- and exocytosis (Fig. 1B and C). Note that fusion and scission are characterized by different intermediate states and, thus by different energy barriers. Therefore, fusion and scission are topologically, but not energetically, opposite processes.

According to our current understanding, the restructuring of the autophagic membrane during the onset of autophagy consists of several steps, which occur sequentially:6 (i) formation of the phagophore; (ii) formation of the autophagosome and (iii) digestion of the autophagosome and its cargo upon fusion with the lysosome. The formation of the autophagosome can be subdivided into bending of the phagophore into a cup-like morphology and… well, how should we actually refer to the last step of autophagosome formation during which the cup-shaped phagophore closes into a double-membrane organelle, the autophagosome?

To find the customary terminology for the last step of autophagosome formation, we analyzed manuscripts covering the topic “autophagy” in the database of Web of Science and looked for expressions describing this particular event. Below, we focus on the 10 most cited reviews for each of 10 years (2004 to 2013), i.e., on 100 highly cited reviews. Whereas reviews published during the last 2 years of the period analyzed acquired between 100 and 1000 citations, all other reviews were cited between 200 and 2000 times, demonstrating the broad recognition of these papers.

A specific description for the last step of autophagosome formation was found in 37 reviews (all others focused on other aspects of autophagy or dealt with topics related to autophagy). The majority of the authors make use of descriptive phrases such as: “closure/sealing/maturation of the phagophore,” “sequestration/engulfment of material within double-membrane structures/organelles” or simply “formation/completion of the autophagosome.” Words such as “enclosure,” “wrapping,” “engulfment” or ”encapsulation” were also used, but rarely. However, in 20 percent of the articles, the term “fusion” was employed, implying that membrane fusion occurred. Examples are “The nascent membranes are fused at their edges to form double-membrane vesicles, called autophagosomes.,”7 “[…] assisting the final fusion of the double-membrane cups into fused vesicles”8 or “The edges of the phagophore then fuse (vesicle completion) to form the autophagosome.”9 The words “scission” or “fission” were not mentioned in any of the reviews.

Phagophores can develop by various pathways, for example: (i) via de novo synthesis,10 (ii) through nucleation at the surface of existing organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum11,12 and (iii) by even more complex membrane processes including membrane fusion processes.13 Irrespective of the actual pathway for phagophore formation, the hallmark of autophagy is the formation of a single autophagosome by closure of the phagophore. The underlying topological transformation generates an inner autophagic vesicle, which is separated from the outer autophagic membrane. At the same time, this process generates 2 separate aqueous compartments, one of which is enclosed by the other. Thus, following the common definitions of membrane fusion and membrane fission/scission (Fig. 1A–C), the mechanism leading to closure of the phagophore (Fig. 1D) is membrane scission. Indeed, from a topological point of view, phagophore closure is equivalent to ESCRT-mediated membrane budding (Fig. 1C and D).14 In both cases, 2 separate aqueous compartments are generated by dissecting a single parental membrane, and one of these aqueous compartments is enclosed in the other.

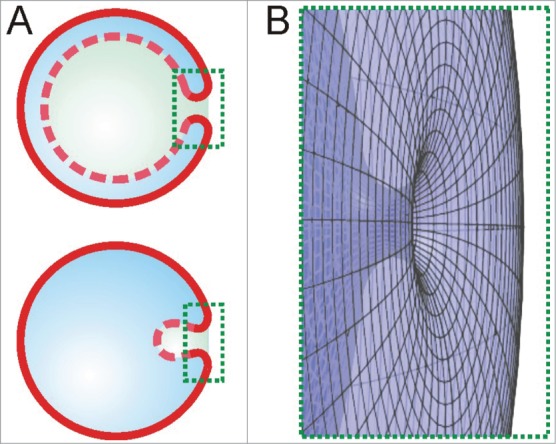

In our review of 100 highly cited reviews, we found that the terms “scission” or “fission” are not used; instead the word “fusion” is commonly used to describe the final step of autophagosome formation (some recent exceptions are found in refs.15,16). Where should we look for the origin of the use of the term “fusion” instead of “scission” in the context of autophagosome formation? In the cross-sections of the phagophores typically published, these organelles often appear to have 2 separate “edges” which seem to undergo a subsequent fusion process (Fig. 1D). However, this interpretation ignores the 3-dimensional shape of the phagophore. Initially, the phagophore has the shape of a double-membrane disk with one circular edge. When this flat phagophore curves into a cup-like shape, the edge develops into a circular neck where membrane scission will occur. This neck structure becomes obvious as soon as we show the structure in 3 dimensions (Fig. 2A and B). However, publications commonly show only cross sections, which reduce the neck to 2 separate, one-dimensional contours. Similarly, 2 edges are visible in micrographs obtained by electron microscopy or simplified 2D illustrations such as Figure 2A. These edges appear to fuse, but the membrane undergoes scission.

Figure 2.

The scission neck. (A) The 2D cross-sectional views show 2 strongly bent membrane segments in the marked rectangular areas during autophagy (upper sketch) and endocytosis (lower sketch). (B) The rotated 3D view of the areas highlighted in (A) reveals that these 2 segments belong to a single scission neck.

In this comment, we have demonstrated that autophagosome closure is based on membrane scission rather than on membrane fusion. In the recent literature, alternative terms such as “sealing,” “maturation” or “closure” have also been used. However, these descriptive terms apply to diverse cellular processes and do not provide mechanistic insight into the underlying molecular events. To circumvent these drawbacks of current terminology and to clarify the primary membrane remodeling process, especially for scientists new in the field, we suggest discontinuing the use of the term “fusion” in the context of phagophore closure and extending descriptive terms in such a way that the underlying mechanism becomes obvious, e.g., “the phagophore closes by membrane scission.” Furthermore, it would be advantageous to employ the term “scission” for other remodeling processes that lead to the same topological transformation such as during viral development17 or the closure of the prespore membrane during spore formation in yeast.18,19

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgment

We thank Jaime Agudo for help with Figure 2B.

Funding

This work is part of the MaxSynBio consortium which is jointly funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany and the Max Planck Society. The study was also supported by the German Science Foundation within the framework of IRTG 1524. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2011; 27:107-32; PMID:21801009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev G, Askew DS, Levine B, Lieberman A, Lim KL, Lin FC, et al.. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 2008; 4:151-75; PMID:18188003; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.5338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipowsky R. Remodeling of membrane compartments: some consequences of membrane fluidity. Biol Chem 2014; 395:253-74; PMID:24491948; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1515/hsz-2013-0244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozlov MM, McMahon HT, Chernomordik LV. Protein-driven membrane stresses in fusion and fission. Trends Biochem Sci 2010; 35:699-706; PMID:20638285; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grafmuller A, Shillcock J, Lipowsky R. Pathway of membrane fusion with two tension-dependent energy barriers. Phys Rev Lett 2007; 98; PMID:17677811; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.218101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knorr RL, Dimova R, Lipowsky R. Curvature of double-membrane organelles generated by changes in membrane size and composition. Plos One 2012; 7:e32753; PMID:22427874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0032753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2011; 18:571-80; PMID:21311563; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2010.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, et al.. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2010; 90:1383-435; PMID:20959619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 2008; 132:27-42; PMID:18191218; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juhasz G, Neufeld TP. Autophagy: a forty-year search for a missing membrane source. Plos Biol 2006; 4:161-4; PMID: 16464128; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi-Nishino M, Fujita N, Noda T, Yamaguchi A, Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A. A subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum forms a cradle for autophagosome formation. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11:1433-U102; PMID:19898463; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez-Wandelmer J, Ktistakis NT, Reggiori F. ERES: sites for autophagosome biogenesis and maturation? J Cell Sci 2015; 128:185-92; PMID:25568152; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.158758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uemura T, Yamamoto M, Kametaka A, Sou YS, Yabashi A, Yamada A, Annoh H, Kametaka S, Komatsu M, Waguri S. A cluster of thin tubular structures mediates transformation of the endoplasmic reticulum to autophagic isolation membrane. Mol Cell Biol 2014; 34:1695-706; PMID:24591649; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01327-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wollert T, Wunder C, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hurley JH. Membrane scission by the ESCRT-III complex. Nature 2009; 458:172-U2; PMID:19234443; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knorr RL, Dimova R, Lipowsky R. Curvature of double-membrane organelles generated by changes in membrane size and composition. Plos One 2012; 7:e32753; PMID: 22427874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0032753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reggiori F, Klionsky DJ. Autophagic processes in yeast: mechanism, machinery and regulation. Genetics 2013; 194:341-61; PMID:23733851; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.112.149013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schauflinger M, Villinger C, Mertens T, Walther P, von Einem J. Analysis of human cytomegalovirus secondary envelopment by advanced electron microscopy. Cell Microbiol 2013; 15:305-14; PMID:23217081; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/cmi.12077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimoda C. Forespore membrane assembly in yeast: coordinating SPBs and membrane trafficking. J Cell Sci 2004; 117:389-96; PMID:14702385; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.00980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neiman AM. Sporulation in the budding yeast saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2011; 189:737-65; PMID:22084423; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.111.127126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]