Abstract

ITPRs (inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors), the main endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+-release channels, were originally proposed as suppressors of autophagy. Yet, new evidence has accumulated over recent years supporting a crucial, stimulatory role for ITPRs in driving the autophagic flux. Here, we provide an integrated view on how ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signaling can have a dual impact on autophagy, depending on the characteristics of the spatio-temporal Ca2+ signals, including the existence of ER-mitochondrial and ER-lysosomal Ca2+ signaling microdomains.

Keywords: autophagic flux; autophagy; Ca2+ microdomains; Ca2+ signaling; inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; spatio-temporal Ca2+ signals

Abbreviations

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- ATP2A/SERCA

ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, cardiac muscle, fast twitch

- BCL2

B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2

- BECN1

Beclin 1, autophagy related

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- ITPR

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3

- TFEB

transcription factor EB

- TGM2

transglutaminase 2

- TMBIM6/BI-1

transmembrane BAX inhibitor motif containing 6

- TPCN

2 pore segment channel

- WIPI1

WD-repeat domain, phosphoinositide interacting 1

During evolution, cells have gradually optimized their intracellular Ca2+-signaling pathways into an intricate system of Ca2+ stores with intralumenal Ca2+-buffering proteins, membrane-inserted Ca2+ pumps and membrane-release channels and cytosolic Ca2+-dependent effectors, together constituting the Ca2+ signalosome.1 The most important intracellular Ca2+ store in mammalian cells is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where the ubiquitously expressed ITPR (inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor) acts as the main intracellular Ca2+-release channel.2 Three isoforms (ITPR1, ITPR2 and ITPR3) contribute to the release of Ca2+ from the ER in response to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), which is produced at the plasma membrane upon exposure of cells to extracellular signals (e.g. ATP, hormones, antibodies, growth factors, neurotransmitters). In this manner, a variety of cellular processes, including cell death and survival, are regulated by ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signaling.3 To control and regulate specific pathways or proteins, physiological Ca2+ signals are tightly but dynamically controlled in a spatiotemporal manner, often involving subcellular Ca2+ microdomains.1,4

ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signaling also influences autophagy. However, seemingly opposing concepts concerning the role of Ca2+ signaling and ITPRs in autophagy have been proposed, with evidence for intracellular Ca2+ signals activating as well as inhibiting the process.5 ITPRs have been proposed as important negative regulators of autophagy since suppressing ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signaling by the depletion of IP3, pharmacological inhibition using the selective ITPR inhibitor Xestospongin B, or the downregulation or knockout of ITPRs, results in an elevation of autophagy markers in vitro.6–11 However, other findings indicate that ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signaling positively influences autophagic cell death in Dictyostelium,12 whereas enhanced ITPR function is critical for driving canonical MTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin [serine/threonine kinase])-dependent autophagy in mammalian cells exposed to nutrient starvation or rapamycin.13,14

Similar to ITPRs, intracellular Ca2+ signaling also appears to play a dual role in autophagy, leading to apparently contradictory results.5 Increase of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) triggered by treatment of cells with extracellular agonist ATP, the ATP2A/SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin or Ca2+ ionophores such as ionomycin, induce an increase in LC3-II levels and in the number of autophagosomes.15 Such an increase in autophagic markers, however, does not necessarily imply the stimulation of autophagy, as it may represent the accumulation of autophagic vesicles due to an inhibition of the autophagic flux. Although Grotemeier et al. still observe a thapsigargin-mediated increase in LC3-II in Jurkat T cells, despite inhibition of the autophagic flux with lysosomal inhibitors,16 other experiments using lysosomal inhibitors indicate that thapsigargin and Ca2+ ionophores rather inhibit the autophagic flux than stimulate autophagy,17,18 thus thereby reducing the degradation of long-lived proteins.19,20 This has both been linked to an effect of thapsigargin on autophagosome-lysosome fusion,18 as well as to an impaired biogenesis of autophagosomes downstream of WIPI1-puncta formation.20 Altogether, these results demonstrate that comparing autophagy in different conditions should be done with great care: treatment of the cells with either thapsigargin or ionophores leads to nonphysiological elevations in Ca2+ with amplitudes and spatio-temporal characteristics that are different from Ca2+ signals triggered by physiological agonists. Moreover, the nature and consequences of these Ca2+ signals are dependent on the applied concentrations of those Ca2+ mobilizers and the duration of the treatment. Finally, a similar Ca2+-dependent inhibitory effect on autophagosome formation is proposed to occur downstream of the plasma membrane L-type Ca2+ channels.17 Antagonists of the latter appear to induce autophagy by a mechanism involving cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent regulation of the IP3 levels and calpain activation. Hence, inhibition of these Ca2+ signals by depleting cellular IP3 levels with lithium chloride is proposed to activate autophagy and thereby to prevent protein aggregation in neurodegeneration.11,17

Different studies using pharmacological inhibitors or ITPR-knockdown approaches6-10 also propose an inhibitory role for the ITPR and the IP3-induced Ca2+ release with respect to autophagy, albeit via different mechanisms. Kroemer and coworkers propose a Ca2+-independent scaffolding role for ITPRs by enhancing the formation of the anti-autophagic BCL2-BECN1/Beclin 1 complex.7 Alternatively, Foskett and coworkers advocate the importance of ITPR-mediated Ca2+ oscillations that drive mitochondrial ATP production, thereby suppressing the activity of AMPK,8 a positive regulator of autophagy.21 As such, DT40 cells in which all 3 ITPR isoforms are genomically deleted display an increased AMPK activation and elevated basal autophagic flux.8

Although these studies indicate that ITPRs are able to inhibit basal autophagy levels, other studies reveal the requirement of ITPR-mediated Ca2+-release during starvation-,13 rapamycin-,14 or natural killer cell22-induced autophagy in mammalian cells and during differentiation factor-induced autophagy in Dictyostelium.12 The different outcomes and the proposed roles of the ITPR in autophagy are possibly due to a divergent role of the ITPRs with respect to basal vs. stress-induced autophagy. Indeed, our study shows that while ITPR inhibition by Xestospongin B stimulates the basal autophagic flux, it also abrogates the starvation-induced autophagic flux.13 In line with the latter view, a recent report by Mikoshiba and coworkers, using the tandem red/green fluorescent protein reporter RFP-GFP-LC3 in HeLa cells reveals that knockdown of ITPR1 leads to an accumulation of autophagosomes.23 Interestingly, the autophagosomes are not randomly located (as observed after treatment with bafilomycin A1), but are restricted to the perinuclear space. Cells in which TGM2 (transglutaminase 2), an ITPR regulator, has been knocked down, show increased ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signaling and display mostly autolysosomes, similar to starvation-subjected cells, indicating enhanced autophagic clearance.23 Although further independent confirmation will be needed, these first data support a concept in which ITPR-mediated Ca2+ release can enhance the trafficking of autophagosomes toward lysosomes, thereby promoting the autophagic flux. In any case, all these different reports strongly advocate the need for proper analysis of the autophagic flux when using Ca2+ mobilizers.

Another important aspect of the complex relation between Ca2+ signaling and autophagy, is the fact that the ER Ca2+ stores are remodeled during autophagy, and the functional properties of the ITPRs are modified by essential autophagy proteins.13,14,24 These findings have implications for autophagy activity, because it has already been demonstrated that autophagy is dependent on the Ca2+ present in the intracellular Ca2+ stores rather than on the extracellular Ca2+.19 Nutrient starvation leads to an overall sensitization of Ca2+-release events from the ER, by increasing the ER Ca2+-store content and by promoting IP3-induced Ca2+ release.13 The former is linked to an increased ER Ca2+-buffering capacity due to an upregulation of ER lumenal Ca2+-binding proteins concomitant with a decreased passive Ca2+ leak from the ER, whereas the latter is linked to a direct interaction of BECN1 with the ITPR, thereby sensitizing the channel toward lower IP3 concentration. Due to their mechanism of action, the use of compounds such as thapsigargin or Ca2+ ionophores will eliminate the functional consequences of these fine-tuned alterations in ER Ca2+ and ITPR function that are critical to drive the autophagic flux. It is interesting to note that autophagy-deficient T cells lacking ATG7 (autophagy related 7) expand their ER Ca2+ stores and increase ER Ca2+ levels by upregulating ATP2A, which may serve as a compensatory mechanism in an attempt to restore autophagic flux.24

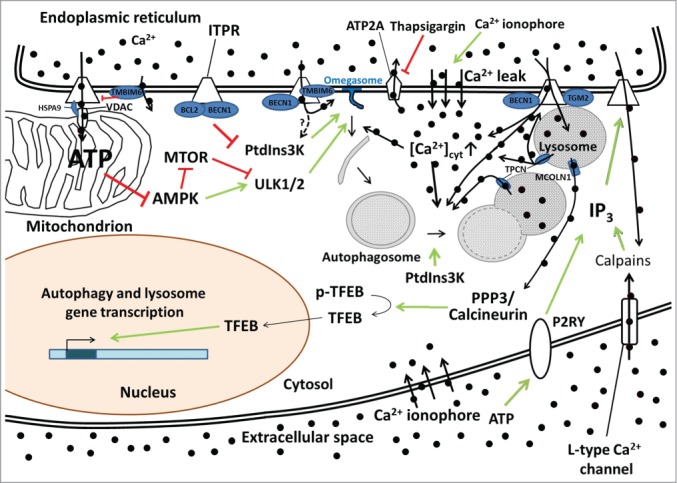

Hence, there is clear evidence that Ca2+ and ITPRs are able to both stimulate and suppress autophagosome synthesis as well as to both enhance and inhibit the autophagic flux. ITPRs and Ca2+ can execute such opposing functions due to the different spatio-temporal characteristics of Ca2+ signals that can be generated, each having distinct impacts on different steps in the autophagy pathway (Fig. 1). Ca2+ signals can vary in the cellular space: large Ca2+ waves can spread out over the entire cell, while local Ca2+ signals, including basal Ca2+ oscillations, can act in a specific cellular microdomain. The probably best known example for this phenomenon is the Ca2+ transfer between ER and mitochondria with specific proteins regulating contact-site formation and efficient Ca2+ signaling between these 2 organelles.25,26 This is in part achieved by the chaperone HSPA9/GRP75 (heat shock 70kDa protein 9 [mortalin]), which physically links ITPRs to VDAC1 (voltage-dependent anion channel 1), the Ca2+-entry channel located at the mitochondrial outer membranes.27 These contact sites are most likely responsible for the ITPR-dependent Ca2+-induced fueling of mitochondrial ATP production and the subsequent suppression of AMPK and autophagy,8,26 as well as for triggering cell death by eliciting mitochondrial Ca2+ overload under specific conditions, and mitophagy by disturbing mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling.26 Furthermore, it should be highlighted that changes in overall ER Ca2+ homeostasis can have very local effects. For instance, lowering the steady-state ER Ca2+ levels will limit the ITPR-driven Ca2+ oscillations and the local transfer of Ca2+ into the mitochondria, thereby compromising mitochondrial ATP production. This mechanism has been proposed to explain the role of TMBIM6/BI-1, an evolutionarily conserved cell-death suppressor28 that acts as an ER Ca2+-leak channel,29,30 a sensitizer of ITPRs,31 and as a positive regulator of autophagy.32 Other possible space-restricted Ca2+ signals that regulate autophagy include local ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signals altering both phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate-rich omegasome formation at the ER membranes via CAMK1 (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 1)33 and accumulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate-binding protein WIPI1.16 Downstream of WIPI1, the thapsigargin-induced impairment of autophagosome biogenesis is shown to be independent of bulk [Ca2+]cyt changes, suggesting local Ca2+ variations account for this effect of thapsigargin.20 Moreover, lysosomes have recently emerged as novel Ca2+ stores that generate Ca2+ signals and that functionally interact with the ER Ca2+-handling mechanisms in a bidirectional way.34–36 Close association of lysosomes with the ER enables rapid exchange of Ca2+ between these organelles, allows the ITPRs to influence the lyso-somal Ca2+ concentration and subsequently Ca2+ release through lysosomal nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)-dependent 2 pore segment channels (TPCNs), whereas NAADP-dependent Ca2+ release can stimulate ITPRs via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. Interestingly, activation of TPCN-mediated Ca2+-signaling inhibits autophagosome-lysosome fusion events by alkalinizing lysosomal pH through an unknown mechanism.37 Underscoring the importance of lysosomal Ca2+ in autophagy, a very recent report demonstrates that nutrient starvation promotes Ca2+ release from the lysosomes through the Ca2+ channel MCOLN1/TRPML1 (mucolipin 1).38 This Ca2+ results in the activation of the protein phosphatase PPP3/calcineurin (protein phosphatase 3) in a microdomain around the lysosomes, and the subsequent dephosphorylation of TFEB, a major transcription factor coordinating lysosomal biogenesis. Dephosphorylated TFEB accumulates in the nucleus, promoting the transcription of genes involved in autophagy and the production of lysosomes.38 Finally, Ca2+ signals from the ER or lysosomes could influence fusion events more directly, since autophagosome maturation is regulated by the Ca2+-binding proteins ANXA1/annexin A1 and ANXA5.39

Figure 1.

The various possible mechanisms of Ca2+-ITPR-mediated control of autophagy. Constitutive ITPR-mediated Ca2+ release into mitochondria inhibits a proximal step in the autophagy pathway by fueling mitochondrial energetics and ATP production and limiting AMPK activity. The ER Ca2+-leak channel TMBIM6 can impede ATP production by lowering the steady-state ER Ca2+ concentration and thus reduce the amount of Ca2+ available for transfer into the mitochondria. ITPRs can also function as scaffolding molecules, thereby suppressing autophagy independently of their Ca2+-release activity by promoting the interaction of BCL2 with BECN1 and thus preventing the formation of the active class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PtdIns3K) complex. ITPR-mediated Ca2+ release can also be enhanced by BECN1 and TMBIM6 and dampened by TGM2, thereby influencing omegasome formation (possibly through PtdIns3K activation) and autophagosome maturation/trafficking. ITPR-mediated Ca2+ release can also influence the lysosomal Ca2+ concentration and lysosomal Ca2+ release through TPCNs, likely influencing lysosomal fusion events, or through MCOLN1, influencing autophagic and lysosomal gene transcription through a pathway involving PPP3/calcineurin and TFEB. TPCNs reciprocally also influence ITPRs via a Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release mechanism. Autophagosome synthesis, maturation and fusion are also affected by Ca2+-mobilizing agents such as thapsigargin (that inhibits the ER Ca2+ pump ATP2A) and Ca2+ ionophores that increase the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt). IP3 production and the subsequent IP3-mediated Ca2+ release can also be regulated by a feedback loop involving calpain activation by L-type Ca2+ channel-mediated Ca2+ entry or the activation of P2RY (purinergic receptor, G-protein coupled). The black circles represent Ca2+ ions, with thick black arrows indicating the direction of the Ca2+ fluxes. Green arrows indicate stimulatory effects, red lines inhibitory ones.

From all these studies, it is clear that there is an intimate interplay between autophagy and Ca2+ signaling from the ER, including via the ITPR channel, likely involving a tight control of the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ signals in space and time. Furthermore, ITPRs and Ca2+ signaling not only affect autophagy, but reciprocally ITPRs and Ca2+ signaling are modulated by the autophagy process in general and by essential autophagy proteins in particular. Hence, considering the complex interrelation between ITPRs and Ca2+ signaling in autophagy, it can be questioned whether the direct pharmacological targeting of these Ca2+-release channels holds potential as a future therapy in autophagy-dependent diseases. However, interesting possibilities lay within the fine-tuning of the Ca2+-flux properties of the channels such as the ITPRs by affecting its dynamic regulation via associated proteins, as has been successfully done with respect to associated anti-apoptotic BCL2 proteins.40,41 For example, BECN1 is recruited by ITPRs during starvation-induced autophagy and sensitizes the ITPRs to low levels of IP3 (Fig. 1).13 In contrast, TGM2, a protein that induces protein crosslinking, counteracts enhanced ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signaling during autophagy stimulation.23 Modulating regulatory proteins acting on the ITPRs could thus fine-tune the ITPR-mediated Ca2+ signals in cells undergoing autophagy, thereby enhancing or reducing the autophagic flux as appropriate. For example, an increase in covalent posttranslational modifications of ITPR1 mediated by TGM2, resulting in a dampened ITPR1 activity, is already found in animal Huntington disease models and in primary B lymphocytes obtained from Huntington patients.23 Limiting TGM2 activity could in those conditions enhance the ITPR-mediated Ca2+ release, stimulate the autophagy pathway and thus increase the autophagy-mediated degradation of mutant HTT (huntingtin). The advantage of such an approach will be that it may not lead to general elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, which has been linked to autophagy inhibition and an impaired clearance of aggregate-prone proteins in neurodegenerative diseases.17

In conclusion, identifying the molecular determinants underlying the formation of multiprotein complexes between the ITPRs and associated regulatory proteins may thus provide new therapeutic avenues to modulate autophagy in the context of human pathologies.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003; 4:517–29; PMID:12838335; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foskett JK, White C, Cheung KH, Mak DO. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol Rev 2007; 87:593–658; PMID:17429043; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00035.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanova H, Vervliet T, Missiaen L, Parys JB, De Smedt H, Bultynck G. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-isoform diversity in cell death and survival. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1843:2164–83; PMID:24642269; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge MJ. Calcium microdomains: organization and function. Cell Calcium 2006; 40:405–12; PMID:17030366; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decuypere JP, Bultynck G, Parys JB. A dual role for Ca2+ in autophagy regulation. Cell Calcium 2011; 50:242–50; PMID:21571367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criollo A, Maiuri MC, Tasdemir E, Vitale I, Fiebig AA, Andrews D, Molgó J, Díaz J, Lavandero S, Harper F, et al.. Regulation of autophagy by the inositol trisphosphate receptor. Cell Death Differ 2007; 14:1029–39; PMID:17256008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vicencio JM, Ortiz C, Criollo A, Jones AW, Kepp O, Galluzzi L, Joza N, Vitale I, Morselli E, Tailler M, et al.. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor regulates autophagy through its interaction with Beclin 1. Cell Death Differ 2009; 16:1006–17; PMID:19325567; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2009.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardenas C, Miller RA, Smith I, Bui T, Molgo J, Muller M, Vais H, Cheung KH, Yang J, Parker I, et al.. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell 2010; 142:270–83; PMID:20655468; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan MT, Joseph SK. Role of inositol trisphosphate receptors in autophagy in DT40 cells. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:16912–20; PMID:20308071; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.114207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong A, Grubb DR, Cooley N, Luo J, Woodcock EA. Regulation of autophagy in cardiomyocytes by Ins(1,4,5)P3 and IP3-receptors. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2013; 54:19–24; PMID:23137780; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkar S, Floto RA, Berger Z, Imarisio S, Cordenier A, Pasco M, Cook LJ, Rubinsztein DC. Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. J Cell Biol 2005; 170:1101–11; PMID:16186256; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200504035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam D, Kosta A, Luciani MF, Golstein P. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor is required to signal autophagic cell death. Mol Biol Cell 2008; 19:691–700; PMID:18077554; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decuypere JP, Welkenhuyzen K, Luyten T, Ponsaerts R, Dewaele M, Molgo J, Agostinis P, Missiaen L, De Smedt H, Parys JB, et al.. Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling and autophagy induction are interrelated. Autophagy 2011; 7:1472–89; PMID:22082873; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.7.12.17909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decuypere JP, Kindt D, Luyten T, Welkenhuyzen K, Missiaen L, De Smedt H, Bultynck G, Parys JB. mTOR-Controlled autophagy requires intracellular Ca2+ signaling. PloS One 2013; 8:e61020; PMID:23565295; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0061020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, Campanella M, Szabadkai G, Farkas T, Bianchi K, Fehrenbacher N, Elling F, Rizzuto R, et al.. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol Cell 2007; 25:193–205; PMID:17244528; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grotemeier A, Alers S, Pfisterer SG, Paasch F, Daubrawa M, Dieterle A, Viollet B, Wesselborg S, Proikas-Cezanne T, Stork B. AMPK-independent induction of autophagy by cytosolic Ca2+ increase. Cell Signal 2010; 22:914–25; PMID:20114074; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams A, Sarkar S, Cuddon P, Ttofi EK, Saiki S, Siddiqi FH, Jahreiss L, Fleming A, Pask D, Goldsmith P, et al.. Novel targets for Huntington's disease in an mTOR-independent autophagy pathway. Nat Chem Biol 2008; 4:295–305; PMID:18391949; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nchembio.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganley IG, Wong PM, Gammoh N, Jiang X. Distinct autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion mechanism revealed by thapsigargin-induced autophagy arrest. Mol Cell 2011; 42:731–43; PMID:21700220; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon PB, Holen I, Fosse M, Rotnes JS, Seglen PO. Dependence of hepatocytic autophagy on intracellularly sequestered calcium. J Biol Chem 1993; 268:26107–12; PMID:8253727 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engedal N, Torgersen ML, Guldvik IJ, Barfeld SJ, Bakula D, Saetre F, Hagen LK, Patterson JB, Proikas-Cezanne T, Seglen PO, et al.. Modulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis blocks autophagosome formation. Autophagy 2013; 9:1475–90; PMID:23970164; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.25900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao M, Klionsky DJ. AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of ULK1 induces autophagy. Cell Metab 2011; 13:119–20; PMID:21284977; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messai Y, Noman MZ, Hasmim M, Janji B, Tittarelli A, Boutet M, Baud V, Viry E, Billot K, Nanbakhsh A, et al.. ITPR1 protects renal cancer cells against natural killer cells by inducing autophagy. Cancer Res 2014; 74:6820–32; PMID:25297632; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamada K, Terauchi A, Nakamura K, Higo T, Nukina N, Matsumoto N, Hisatsune C, Nakamura T, Mikoshiba K. Aberrant calcium signaling by transglutaminase-mediated posttranslational modification of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111(38):E3966–75; PMID:25201980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1409730111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia W, Pua HH, Li QJ, He YW. Autophagy regulates endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and calcium mobilization in T lymphocytes. J Immunol 2011; 186:1564–74; PMID:21191072; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1001822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchi S, Patergnani S, Pinton P. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connection: one touch, multiple functions. Biochim et Biophys Acta 2014; 1837:461–9; PMID:24211533; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rimessi A, Bonora M, Marchi S, Patergnani S, Marobbio CM, Lasorsa FM, Pinton P. Perturbed mitochondrial Ca2+ signals as causes or consequences of mitophagy induction. Autophagy 2013; 9:1677–86; PMID:24121707; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.24795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Varnai P, De Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, Nagy AI, Balla T, Rizzuto R. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol 2006; 175:901–11; PMID:17178908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200608073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Q, Reed JC. Bax inhibitor-1, a mammalian apoptosis suppressor identified by functional screening in yeast. Mol Cell 1998; 1:337–46; PMID:9660918; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80034-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bultynck G, Kiviluoto S, Henke N, Ivanova H, Schneider L, Rybalchenko V, Luyten T, Nuyts K, De Borggraeve W, Bezprozvanny I, et al.. The C terminus of Bax inhibitor-1 forms a Ca2+-permeable channel pore. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:2544–57; PMID:22128171; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M111.275354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bultynck G, Kiviluoto S, Methner A. Bax inhibitor-1 is likely a pH-sensitive calcium leak channel, not a H+/Ca2+ exchanger. Sci Signal 2014; 7:pe22; PMID:25227609; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scisignal.2005764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiviluoto S, Schneider L, Luyten T, Vervliet T, Missiaen L, De Smedt H, Parys JB, Methner A, Bultynck G. Bax inhibitor-1 is a novel IP3 receptor-interacting and -sensitizing protein. Cell Death Dis 2012; 3:e367; PMID:22875004; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cddis.2012.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sano R, Hou YC, Hedvat M, Correa RG, Shu CW, Krajewska M, Diaz PW, Tamble CM, Quarato G, Gottlieb RA, et al.. Endoplasmic reticulum protein BI-1 regulates Ca2+-mediated bioenergetics to promote autophagy. Genes Dev 2012; 26:1041–54; PMID:22588718; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.184325.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfisterer SG, Mauthe M, Codogno P, Proikas-Cezanne T. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) signaling via CaMKI and AMP-activated protein kinase contributes to the regulation of WIPI-1 at the onset of autophagy. Mol Pharmacol 2011; 80:1066–75; PMID:21896713; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1124/mol.111.071761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan AJ, Davis LC, Wagner SK, Lewis AM, Parrington J, Churchill GC, Galione A. Bidirectional Ca2+ signaling occurs between the endoplasmic reticulum and acidic organelles. J Cell Biol 2013; 200:789–805; PMID:23479744; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201204078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kilpatrick BS, Eden ER, Schapira AH, Futter CE, Patel S. Direct mobilisation of lysosomal Ca2+ triggers complex Ca2+ signals. J Cell Sci 2013; 126:60–6; PMID:23108667; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.118836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopez-Sanjurjo CI, Tovey SC, Prole DL, Taylor CW. Lysosomes shape Ins(1,4,5)P3-evoked Ca2+ signals by selectively sequestering Ca2+ released from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci 2013; 126:289–300; PMID:23097044; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.116103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu Y, Hao BX, Graeff R, Wong CW, Wu WT, Yue J. Two pore channel 2 (TPC2) inhibits autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion by alkalinizing lysosomal pH. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:24247–63; PMID:23836916; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.484253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Medina DL, Di Paola S, Peluso I, Armani A, De Stefani D, Venditti R, Montefusco S, Scotto-Rosato A, Prezioso C, Forrester A, et al.. Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat Cell Biol 2015; 17:288–99; PMID:25720963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb3114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghislat G, Knecht E. New Ca2+-dependent regulators of autophagosome maturation. Commun Integr Biol 2012; 5:308–11; PMID:23060949; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cib.20076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong F, Harr MW, Bultynck G, Monaco G, Parys JB, De Smedt H, Rong YP, Molitoris JK, Lam M, Ryder C, et al.. Induction of Ca2+-driven apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by peptide-mediated disruption of Bcl-2-IP3 receptor interaction. Blood 2011; 117:2924–34; PMID:21193695; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akl H, Monaco G, La Rovere R, Welkenhuyzen K, Kiviluoto S, Vervliet T, Molgó J, Distelhorst CW, Missiaen L, Mikoshiba K, et al.. IP3R2 levels dictate the apoptotic sensitivity of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells to an IP3R-derived peptide targeting the BH4 domain of Bcl-2. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4:e632; PMID:23681227; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cddis.2013.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]