Abstract

Background: Maternal smoking during pregnancy represents a significant developmental risk for the unborn child. This study investigated social differences in maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy in mothers living in Germany. The study focused on maternal age at delivery, social status and migration background. Method: The evaluation of data was based on two surveys carried out as part of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS) carried out in 2003–2006 and in 2009–2012. The study compared the information given by parents of children aged between 0 and 6 years who were born either in the period from 1996 to 2002 (KiGGS baseline study, n = 4818) or in the period from 2003 to 2012 (KiGGS Wave 1, n = 4434). Determination of social status was based on parental educational levels, occupational position and income. Children classified as having a two-sided migration background either had parents, both of whom had immigrated to Germany, or were born abroad and had one parent who had immigrated to Germany; children classified as having a one-sided migration background had been born in Germany but had one parent who had immigrated to Germany. Results: The percentage of children whose mothers had smoked during pregnancy was 19.9 % for the older birth cohort and 12.1 % for the younger birth cohort. In both birth cohorts, the probability of being exposed to tobacco smoke was twice as high for children whose mothers were aged < 25 years at delivery compared to the children of older mothers. Children from socially deprived families were most affected by smoking behavior, and the relative social differences were found to have even increased over time (KiGGS baseline study: OR = 6.34; 95 % CI = 4.53–8.86; KiGGS Wave 1: OR = 13.88; 95 % CI = 6.85–28.13). A two-sided migration background was associated with a lower risk of exposure to smoking. Conclusions: The KiGGS results are in accordance with the results of other national and international studies which have shown that the percentage of mothers who smoke during pregnancy is declining. Because of a change in the method how data are collected for the KiGGS survey (written questionnaire vs. telephone interview) the trend results must be interpreted with caution. Measures aimed at preventing smoking and weaning women off smoking should focus particularly on younger and socially deprived mothers.

Key words: maternal smoking, pregnancy, social status, migration background, health inequality

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund: Das mütterliche Rauchen während der Schwangerschaft stellt für die Entwicklung des ungeborenen Kindes ein erhebliches Risiko dar. Untersucht werden soziale Unterschiede im Rauchverhalten während der Schwangerschaft bei Müttern in Deutschland. Das Alter der Mutter bei der Geburt des Kindes, der Sozialstatus und ein etwaiger Migrationshintergrund stehen dabei im Fokus. Methodik: Die Auswertungen beruhen auf 2 Erhebungen der Studie zur Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland (KiGGS), die im Zeitraum von 2003–2006 bzw. 2009–2012 durchgeführt wurden. Verglichen werden die Angaben der Eltern 0- bis 6-jähriger Kinder, die im Zeitraum von 1996 bis 2002 (KiGGS-Basis, n = 4818) bzw. 2003 bis 2012 (KiGGS Welle 1, n = 4434) geboren wurden. Der Sozialstatus wird anhand der Bildung, des Berufs und des Einkommens der Eltern ermittelt. Kinder mit beidseitigem Migrationshintergrund haben entweder Eltern, die beide zugewandert sind, oder aber ein zugewandertes Elternteil und sind selbst im Ausland geboren, während Kinder mit einseitigem Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland geboren sind, aber ein zugewandertes Elternteil haben. Ergebnisse: Der Anteil der Kinder, deren Mütter während der Schwangerschaft geraucht haben, lag in der älteren Geburtskohorte bei 19,9 %, in der jüngeren bei 12,1 %. Kinder, deren Mütter bei Geburt < 25 Jahre alt waren, sind in beiden Geburtskohorten rund doppelt so häufig Tabakrauch ausgesetzt gewesen wie Kinder älterer Mütter. Am stärksten betroffen sind Kinder aus sozial benachteiligten Familien, wobei die relativen sozialen Unterschiede im Zeitverlauf sogar noch zugenommen haben (KiGGS-Basis: OR = 6,34; 95 %-KI = 4,53–8,86; KiGGS Welle 1: OR = 13,88; 95 %-KI = 6,85–28,13). Ein beidseitiger Migrationshintergrund ist mit einem geringeren Expositionsrisiko assoziiert. Schlussfolgerungen: Die KiGGS-Ergebnisse sprechen im Einklang mit nationalen und internationalen Studien dafür, dass der Anteil der Mütter, die während der Schwangerschaft rauchen, rückläufig ist. Aufgrund des Methodenwechsels in KiGGS (schriftliche vs. telefonische Befragung) sind die Trendergebnisse jedoch vorsichtig zu interpretieren. Maßnahmen der Tabakprävention und -entwöhnung sollten insbesondere junge und sozial benachteiligte Mütter in den Blick nehmen.

Schlüsselwörter: mütterliches Rauchen, Schwangerschaft, Sozialstatus, Migrationshintergrund, gesundheitliche Ungleichheit

Introduction

Health starts in the womb, and maternal smoking during pregnancy represents a significant developmental risk for the unborn child 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The toxic substances present in tobacco smoke can damage the placenta, which is why the rates for pregnancy complications such as miscarriage, prematurity and stillbirth are higher for women who smoke 6, 7, 8. Nicotine, carbon monoxide and other harmful substances enter the fetal blood circulation and impair the supply of oxygen to the fetus, thus inhibiting key growth and maturation processes. The neonates born to women who smoke are, on average, both smaller and lighter and have a smaller head circumference at birth compared to children of mothers who do not smoke 9, 10, 11. Maternal smoking during pregnancy promotes the occurrence of congenital malformations such as cleft nose, lip and palate 12, 13 and is also a key risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) 14, 15, 16. Over the longer term, maternal smoking during pregnancy also increases the risk for numerous diseases and developmental disorders, including asthma 17, 18, 19, otitis media 20, 21, overweight and obesity 22, 23, 24, 25, and behavioral problems 26, 27, 28, 29. The health consequences of smoking during pregnancy are associated with significant economic burden and involve substantial costs for the healthcare system 30, 31.

Stopping smoking before or during pregnancy can significantly reduce the risk of complications of pregnancy and lower the negative impact on the health of mother and child 32, 33, 34. From a public health point of view, preventing pregnant women and women of childbearing age from smoking or weaning them off smoking has assumed a great importance 35. The public health target “Reduce tobacco consumption” was developed as one of the national public health targets and updated in 2015; one of the five sub-goals was reducing maternal smoking during pregnancy 36. Repeated epidemiological studies on the prevalence of smoking in pregnant women are necessary to monitor target achievement. It is the only way to identify risk groups and develop suitable approaches to reduce maternal smoking during pregnancy and to evaluate the efficacy of the approaches used 37, 38.

International studies have shown that in most westernized countries a significant percentage of women still smoke during pregnancy, although in many countries the existing data point to a decline in the prevalence of maternal smoking over the last ten to twenty years 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42. Currently, the percentage of women who smoke during pregnancy is 10.7 % in the USA (2010) 43, 14.3 % in Canada (2003–2011/12) 44, 14.5 % in Australia (2009) 40, 12.7 % in England (2012/2013) 45, 21.7 % in France (2011) 46 6.3 % in the Netherlands (2010) 41, 21.1 % in Iceland (2001–2010) 47, 16.5 % in Norway (2009), 15 % in Finland (2010) 39, 12.5 % in Denmark (2010) 39 and 6.9 % in Sweden (2008) 39.

In Germany the available data on the prevalence of maternal smoking during pregnancy is comparatively poor. Other than a few regional studies 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 there are only a few surveys which provide data for all of Germany 35, 54, 55, 56, 57. The information is generally based on the data collected during German perinatal surveys, during which all women who give birth in hospital are also asked how many daily cigarettes they continued to smoke after they knew that they were pregnant. Based on these data, Schneider et al. reported that the prevalence of maternal smoking during pregnancy in Germany in 2005 was 12.4 % 55. Scholz et al. came to the conclusion that a comparison of the birth cohorts for the periods 1995–1997 and 2007–2011 showed that the percentage of pregnant women who smoked had dropped from 23.5 to 11.2 % 56.

Both international and national studies have concurred in showing that there are significant demographic and social differences with regard to the distribution of maternal smoking behavior in pregnancy. Particularly young, poorly educated and socially deprived women are significantly more likely to smoke during pregnancy than older, better educated and socially better-off pregnant women 35, 37, 41, 42, 44, 50, 58. There are only a few studies on the impact of a migration background on maternal smoking 46, 55, 58, 59.

This study was based on data collected by the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) as part of its German Health Interview and Examination Survey of Children and Adolescents (KiGGS) and focuses primarily on three issues: how high is the percentage of women in Germany who smoke during pregnancy? What role do maternal age at delivery, social status and migration background play for maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy? How have social differences in maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy developed based on a comparison of two birth cohorts (1996–2002 and 2003–2012)?

Method

Data basis

KiGGS is part of the health monitoring system of the RKI and was designed as a combined cross-sectional and cohort study. The goals, concept and design of the KiGGS study have been described in detail elsewhere 60, 61, 62, 63. KiGGS aims to repeatedly obtain national prevalence data for the state of health of children and adolescents living in Germany and covering an age range of 0–17 years. The KiGGS baseline study (2003–2006) consisted of surveys, medical examinations, tests and laboratory analyses; KiGGS Wave 1 (2009–2012) was carried out as a telephone-based survey. The KiGGS baseline study was a pure cross-sectional study of a total of 17 641 surveyed persons aged 0–17 years and had a participation rate of 66.6 %. The names of persons invited to participate were obtained by stratified random sampling in 167 locations across Germany and were drawn by chance from the population registers 61. The sample used in KiGGS Wave 1 consisted – on the one hand – of a new cross-sectional sample of children aged 0 to 6 years, who in their turn were again drawn by chance from the population registers of the original study locations. However, KiGGS Wave 1 also invited the former participants of the original KiGGS baseline study to participate in the survey again. The telephone interviews were carried out by trained study staff from the RKI. Prior to starting the study, the Ethics Commission of the Charité/University Medicine Berlin and the German Federal Commissioner for Data Protection had approved the study. Patients were only surveyed or interviewed after the person(s) who were responsible for their care had been informed about the purpose and extent of the study and given their written consent or – once the test person had come of age – after obtaining the participantʼs own written consent. A total of 12 368 children and adolescents aged from 0–17 years and thus relevant for the cross-sectional study participated in the study, of whom 4455 had been invited to participate for the first time (response rate 38.8 %) and 7913 had been invited to participate for the second time (response rate 72.9 %) 63.

Maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy

The evaluation of maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy was limited to the information provided for children aged between 0 and 6 years. The KiGGS baseline study used information provided by parents whose children were born in the years 1996–2002 (n = 4818). KiGGS Wave 1 included data for the birth cohorts of 2003–2012 (n = 4434) (Table 1). To prevent an overlap of birth cohorts, the birth cohorts of 2003–2006 from the KiGGS baseline study (n = 1862) and the birth cohort for the year 2002 from KiGGS Wave 1 (n = 21) were subsequently excluded from the analysis. Respondents were asked: “Did the mother of the child smoke during pregnancy?” (Response categories: “Yes, regularly”, “Yes, occasionally”, “No, never”); the figures for the two assenting response categories were then combined below 64, 65. Neither the question nor the preset response categories were changed from the KiGGS baseline study to KiGGS Wave 1. Although it is important to take account of the changed mode of data collection (written questionnaire vs. telephone interview), keeping the question and the response categories the same made it possible to make a statement about changes in maternal smoking behavior over time by comparing two birth cohorts (1996–2002 and 2003–2012).

Table 1 Description of random sampling in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey of Children and Adolescents (KiGGS) with regard to children aged 0–6 years.

| KiGGS baseline study (2003–2006) (n = 4 818)Birth cohorts: 1996–2002 | KiGGS Wave 1 (2009–2012) (n = 4 434)Birth cohorts: 2003–2012 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | Number of cases (n) | Unweighted sample (%) | Weighted samplea (%) | Number of cases (n) | Unweighted sample (%) | Weighted samplea (%) |

| a Weighted figures excluding the number of persons for whom no data was available (official population size on 31. 12. 2010, distribution of the educational level of the head of the household according to the 2009 microcensus) | |||||||

| Age of the child | 0 years | 68 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 634 | 14.3 | 11.7 |

| 1 year | 299 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 641 | 14.5 | 14.4 | |

| 2 years | 591 | 12.3 | 13.0 | 667 | 15.0 | 14.8 | |

| 3 years | 919 | 19.1 | 19.5 | 601 | 13.6 | 14.9 | |

| 4 years | 982 | 20.4 | 19.4 | 663 | 15.0 | 14.6 | |

| 5 years | 953 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 633 | 14.3 | 14.9 | |

| 6 years | 1 006 | 20.9 | 20.3 | 595 | 13.4 | 14.8 | |

| Gender | Boys | 2 435 | 50.5 | 51.4 | 2 282 | 51.5 | 51.4 |

| Girls | 2 383 | 49.5 | 48.6 | 2 152 | 48.5 | 48.6 | |

| Age of the biological mother at delivery | Up to 24 years | 779 | 16.2 | 17.2 | 417 | 9.4 | 13.7 |

| 25 to 29 years | 1 399 | 29.0 | 28.5 | 1 175 | 26.5 | 26.7 | |

| 30 to 34 years | 1 699 | 35.3 | 36.4 | 1 599 | 36.1 | 33.2 | |

| 35+ years | 815 | 16.9 | 17.8 | 1 205 | 27.2 | 26.4 | |

| Missing | 126 | 2.6 | – | 38 | 0.9 | – | |

| Social status | Low | 754 | 15.6 | 19.9 | 358 | 8.1 | 17.4 |

| Moderate | 2 821 | 58.6 | 58.6 | 2 673 | 60.3 | 59.3 | |

| High | 1 181 | 24.5 | 21.4 | 1 401 | 31.6 | 23.3 | |

| Missing | 62 | 1.3 | – | 2 | 0.0 | – | |

| Migration background | Two-sided | 682 | 14.2 | 18.5 | 299 | 6.7 | 12.8 |

| One-sided | 404 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 409 | 9.2 | 10.0 | |

| None | 3 686 | 76.5 | 71.6 | 3 721 | 83.9 | 77.1 | |

| Missing | 46 | 1.0 | – | 5 | 0.1 | – | |

| Mother smoked during pregnancy | Yes, regularly | 234 | 4.9 | 6.3 | 91 | 2.1 | 3.9 |

| Yes, occasionally | 588 | 12.2 | 13.6 | 243 | 5.5 | 8.3 | |

| No, never | 3 870 | 80.3 | 80.1 | 4 088 | 92.2 | 87.9 | |

| Missing | 126 | 2.6 | – | 12 | 0.3 | – | |

Sociodemographic and socio-economic determinants

Maternal age at delivery was calculated based on information about the motherʼs current age and age of the child at the time of participating in the KiGGS baseline study or KiGGS Wave 1. The following categories were created for analysis: < 25 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, 35+ years (Table 1).

Social status was determined using an index developed by the RKI, which combines information provided by the parent on their education and their vocational training, their occupational position, and their income, and allows participants to be categorized as low, moderate or high status group 66 (Table 1).

Data on migration background was compiled based on information about the childrenʼs own experience of immigration together with information on the country of birth and the nationality of both parents. Children who had immigrated to Germany from another country and who had at least one parent who was not born in Germany and children, both of whose parents had immigrated to Germany, and children whose parents were not German citizens were categorized as having a two-sided migration background. Children were classified as having a one-sided migration background if they had been born in Germany but one parent had immigrated to Germany from another country and/or did not hold German citizenship 67, 68, 69 (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

All analysis was done using a weighting factor which corrected for deviations of the sample from the population structure (as per 31. 12. 2010) with respect to age, gender, region, nationality, type of community and level of education of the head of the household (Microcensus 2009) 63. Outcomes were reported as prevalences with 95 % confidence intervals and looked at differences in maternal age at the time of delivery, social status and migration background. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) to show potential demographic and social differences in the distribution of maternal smoking. The odds ratios indicate the factor by which the statistical odds that the mother smoked during pregnancy increases or decreases for children in one group compared to the children from another predetermined, reference group.

To take account of both the weighting and the correlation between participants of a community, confidence intervals and p-values were calculated using methods to analyze complex samples. Differences between groups were tested for significance using the F-distribution or Rao-Scott adjusted χ2-Test for complex samples. Differences were considered statistically significant when confidence intervals did not overlap or the probability of error (p) was less than 0.05. Calculations were done using the software program IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20.

Results

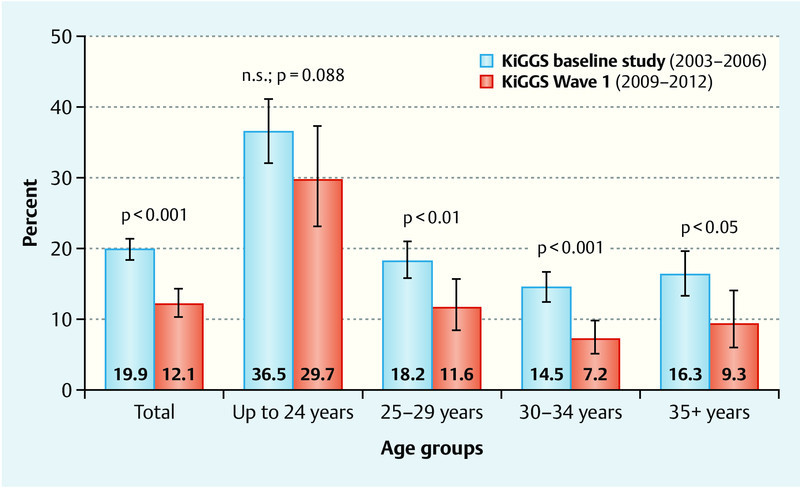

Overall development over time and impact of maternal age at delivery

The KiGGS data show that when the birth cohorts of 1996–2002 are compared with the birth cohorts of 2003–2012, the percentage of children aged 0 to 6 years whose mothers smoked during pregnancy declined from 19.9 to 12.1 %. As shown in Fig. 1, the prevalence of smoking decreased irrespective of maternal age at the time of delivery; only the group which included the youngest mothers showed no statistical differences between the two birth cohorts. It was striking, however, that in both birth cohorts, children whose mothers were younger than 25 years were twice as likely to be exposed to tobacco smoke in the womb compared to children whose mothers were older.

Fig. 1.

Trends in smoking behavior during pregnancy for the mothers of children aged 0 to 6 years, according to the age of the biological mother at the time of delivery. Results of the KiGGS baseline study and KiGGS Wave 1 adjusted for the 2009/2010 population structure.

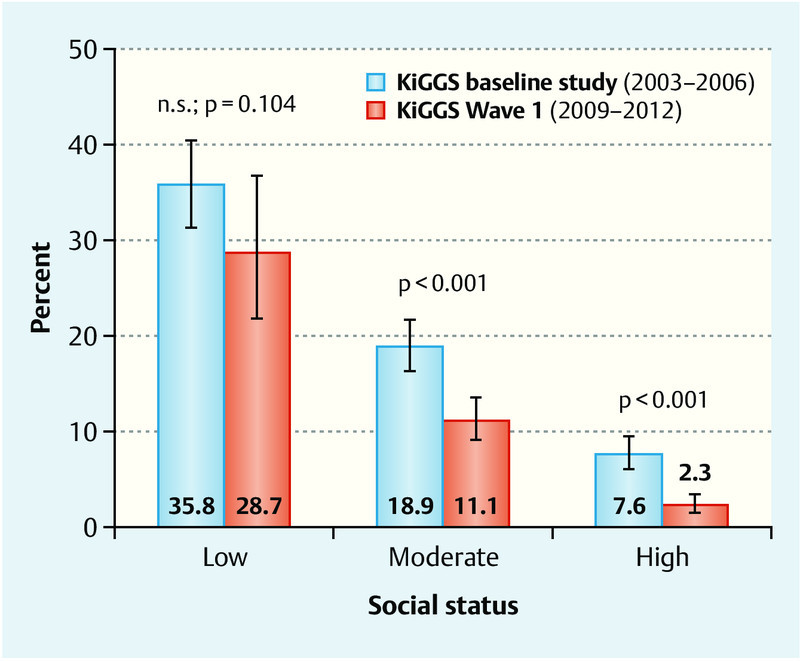

Maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy according to social status

Socio-economic differences in maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy were particularly pronounced. The social gradient was statistically significant in both birth cohorts (Fig. 2): the higher the social status, the lower the percentage of children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy. A comparison of both birth cohorts showed that the prevalence of smoking only declined significantly in the moderate and high status groups, while the decrease in maternal smoking was not statistically significant in the low status group.

Fig. 2.

Trends in smoking behavior during pregnancy for the mothers of children aged 0 to 6 years, according to social status. Results of the KiGGS baseline study and KiGGS Wave 1 adjusted for the 2009/2010 population structure.

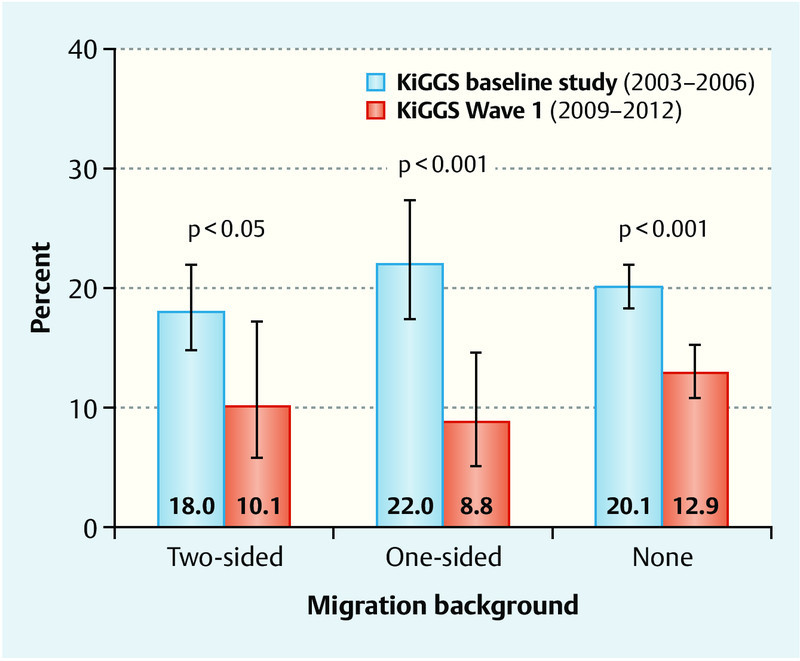

Maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy according to migration background

Differences in maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy were less striking when the migration background of the children was considered. While the percentage of children with two-sided, one-sided or no migration background whose mothers smoked during pregnancy was between 18 and 22 % in the birth cohorts of 1996–2002, these percentage dropped to around 9 to 13 % for the birth cohorts of 2003–2012 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Trends in smoking behavior during pregnancy for mothers of children aged 0 to 6 years according to migration background. Results of the KiGGS baseline study and KiGGS Wave 1 adjusted for the 2009/2010 population structure.

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis showed an independent impact of maternal age at the time of delivery and of the familyʼs social status on maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy for both birth cohorts (Table 2, Model 1). It should be recognized, however, that maternal age at the time of delivery, social status and migration background are closely interconnected. It is known, for example, that socially deprived women give birth on average at a significantly younger age compared to women who have a socially higher status, and it is also known that children from immigrant families grow up significantly more often in socially deprived conditions than children with no migration background.

Table 2 Trends for social differences in maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy for mothers of children aged 0 to 6 years. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratios (OR), 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) and p-values. Results of the KiGGS baseline study and KiGGS Wave 1 adjusted for the 2009/2010 population structure.

| KiGGS baseline study (2003–2006)Birth cohorts: 1996–2002 | KiGGS Wave 1 (2009–2012)Birth cohorts: 2003–2012 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| OR (95 % CI)p-value | OR (95 %-CI)p-value | OR (95 % CI)p-value | OR (95 % CI)p-value | |

| Model 1: adjusted for age and gender of the child; Model 2: additionally reciprocally adjusted for the age of the biological mother at the time of delivery, social status, and migration background; bold = significant result. | ||||

| Age of the biological mother at delivery | ||||

|

2.95 (2.19–3.96) p < 0.001 | 2.05 (1.52–2.77) p < 0.001 | 4.11 (2.28–7.42) p < 0.001 | 2.19 (1.13–4.24) p < 0.05 |

|

1.14 (0.88–1.48)p = 0.324 | 0.96 (0.74–1.25)p = 0.751 | 1.28 (0.70–2.34)p = 0.426 | 1.00 (0.55–1.83)p = 0.999 |

|

0.87 (0.65–1.15)p = 0.318 | 0.80 (0.60–1.07)p = 0.131 | 0.75 (0.42–1.35)p = 0.334 | 0.75 (0.42–1.35)p = 0.340 |

|

Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Social status | ||||

|

6.75 (4.87–9.37) p < 0.001 | 6.30 (4.52–8.80) p < 0.001 | 17.49 (9.74–31.41) p < 0.001 | 13.88 (6.85–28.13) p < 0.001 |

|

2.83 (2.18–3.67) p < 0.001 | 2.55 (1.95–3.33) p < 0.001 | 5.42 (3.38–8.69) p < 0.001 | 4.97 (3.06–8.08) p < 0.001 |

|

Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Migration background | ||||

|

0.88 (0.68–1.14)p = 0.316 | 0.48 (0.35–0.65) p < 0.001 | 0.76 (0.40–1.46)p = 0.407 | 0.49 (0.23–1.03)p = 0.059 |

|

1.12 (0.81–1.56)p = 0.476 | 0.85 (0.57–1.26)p = 0.415 | 0.65 (0.36–1.17)p = 0.147 | 0.85 (0.48–1.52)p = 0.582 |

|

Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

In the second model shown in Table 2 the results were therefore additionally statistically adjusted for these interconnections. It was found that in both birth cohorts, the risk of being exposed to tobacco smoke in the womb was almost double for the children of mothers younger than 25 years at the time of delivery compared to children whose mothers were at least 35 years old – irrespective of social status or migration background. Children whose mothers were between 25 and 34 years old at the time of delivery were not at greater risk of exposure to smoke in the womb than the children of older mothers.

The comparison of the two birth cohorts showed that relative social differences had significantly increased over time. While the risk of maternal smoking during pregnancy for children with a low or moderate social status in the birth cohorts 1996–2002 was higher by a factor of 6.3 and 2.6, respectively, compared to children with a high social status in the same birth cohorts, the respective odds ratios for the birth cohorts 2003–2012 were 13.9 and 5.0. But when the often poorer social situation of immigrant families was also taken into account, a two-sided migration background appeared to exert a protective effect on maternal smoking during pregnancy. It was found that the risk of exposure to cigarette smoke during pregnancy for children in both birth cohorts who had a two-sided migration background was only around half of that of children with no migration background, although these differences were only statistically significant for the older birth cohorts. The risk of exposure to smoke in the womb for children with a one-sided migration background did not differ from that of children with no migration background.

Discussion

The results of the KiGGS study suggest that the percentage of mothers who smoked during pregnancy has decreased significantly over the last twenty years. While every fifth mother of a child born in the period 1996–2002 smoked during pregnancy, only every eighth mother of a child born between 2003 and 2012 smoked during pregnancy (19.9 vs. 12.1 %). These KiGGS data are largely commensurate with and correspond to the data presented by Scholz et al. on the prevalence of maternal smoking during pregnancy which are based on the German perinatal survey (birth cohorts 1995–1997: 23.5 %, 2007–2011: 11.2 %) 56. The percentage of women who smoke during pregnancy has decreased significantly since the 1990s, not just in Germany but in most westernized countries 39, 41, 42, 45.

Despite this welcome development, there are still certain risk groups where smoking is especially common. If maternal age at the time of delivery is considered, then the KiGGS data showed that young women were the most likely group to smoke during pregnancy. With a percentage of around 30 % in the birth cohorts of 2003–2012, the percentage of mothers who smoked during pregnancy is particularly high among women under 25 years of age. This finding was confirmed in numerous national 48, 55 and international 37, 39, 42, 58 studies.

The KiGGS data also prove for both birth cohorts that children with a low social status are exposed significantly more often to tobacco smoke before they are born than children with a moderate social status, and, in turn, that children with a moderate social status are exposed significantly more often to tobacco smoke in the womb than children with a high social status. This social gradient in maternal smoking behavior was also reported in the overwhelming majority of national 35, 48, 55 and international studies 37, 39, 41, 42, 58. In a Dutch study started in the period 2009–2011 the prevalence of maternal smoking for pregnant women was 25.4, 11.4 and 2.6 %, respectively, for low, moderate and high social status groups 58, a distribution pattern that was found to be very similar to that for children with low (28.7 %), moderate (11.1 %) or high social status (2.3 %) in the KiGGS birth cohorts of 2003–2012.

The significance of a migration background for maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy initially appeared to be less clear. The prevalences for children with two-sided, one-sided or no migration background did not differ much between both birth cohorts. Only after a statistical analysis which also considered the – on average – poorer social situation and younger maternal age at delivery was it possible to show that the risk of exposure to smoking in the womb for children with a two-sided migration background was almost half that of children without a migration background. The risk of exposure to smoke in the womb for children with a one-sided migration background did not differ significantly from that of children without a migration background. As persons with a migration background form a highly heterogeneous population with regard to their country of origin, religion and culture, it can be assumed that maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy is also likely to differ significantly between different groups of immigrant women. Because of the lack of case numbers it has not been possible to carry out corresponding subgroup analyses. As part of a special statistical evaluation of the German perinatal survey of 2005, Schneider et al. reported that mothers of foreign nationality were significantly less likely to smoke during pregnancy than women of German nationality 55. In the Berlin perinatal study of 2011/2012 the percentage of pregnant women who reported smoking during pregnancy was 19.8 % for women born in Turkey and 17.8 % for German women 59. However, significant differences were found depending on the length of stay in Germany, the degree of integration and the womenʼs language skills in German. The percentage of Turkish women who smoked during pregnancy was found to be lower for Turkish women who had spent less time in Germany, were less integrated and whose language skills in German were lower. In the French ELFE study, 21.9 % of women born in France reported that they had smoked while pregnant; the corresponding figure for immigrant women not born in France was significantly lower, amounting to just 8.8 % 46.

Importance of the findings for policy decisions, health promotion and prevention programs in pregnancy

Reducing maternal smoking during pregnancy is an important goal of healthcare policy. This is not only expressed by the German health target “Reduce tobacco consumption” 36. In addition to ten core indicators, the “European Perinatal Health Report 2010” also lists maternal smoking during pregnancy as one of twenty recommended indicators which require regular monitoring 38. In Australia, reducing pregnant womenʼs consumption of tobacco products is the first point on the list of the “10 national core maternity indicators” 40.

There are several reasons why the finding that a lower percentage of women smoke during pregnancy compared to ten or twenty years ago is plausible. The KiGGS results have highlighted a development which – as mentioned before – is reflected both in the data of German perinatal surveys and from a number of international studies. At the early years of the millennium a number of tobacco control measures were introduced both in Germany and across Europe; these measures aimed to reduce the consumption of tobacco and the exposure to secondhand smoke in the general population and specifically among certain vulnerable groups such as pregnant women 70. Since about 2003 cigarette packs in all EU member states must display written warnings such as “Smoking during pregnancy can harm your baby”. In addition, the increased taxes on tobacco have led to a perceptible increase in the price of cigarettes and other tobacco products 71. Since 2007 a number of laws to protect non-smokers were passed in Germany which led to a comprehensive smoking ban on public transport and in public buildings, hospitals, restaurants and pubs. Data from the microcensus show that in this context, the percentage of women of reproductive age (15–39 years) who smoke has successively declined in the period from 2003 to 2013, dropping from 31.0 to 25.4 % 72. And a comparison of the birth cohorts for 1996–2002 with those of the birth cohorts of 2003–2012 shows that the percentage of mothers of children aged 0 to 6 years who reported that they smoked at the time of inclusion in the KiGGS study has decreased from 31.8 to 25.2 %.

Pregnancy is an appropriate point in time for interventions aimed at changing behavior (“window of opportunity”) 5. These results from the KiGGS survey are in accordance with the results of other studies and show that young women and socially deprived women are disproportionately more likely to smoke during pregnancy. They are therefore particularly important target groups for public information campaigns and for health promotion and health prevention measures initiated before and after giving birth. Doctors, midwives and professionals who regularly work with pregnant women should inform women who smoke about the real risks of smoking, give recommendations on how to quit smoking and provide information on appropriate and available measures of support to quit smoking.

Strengths and limitations of this study

These results are based on representative data obtained across all of Germany. While German perinatal surveys only look at the smoking status of pregnant women who give birth in hospital, the KiGGS study also includes the data of women who gave birth outside hospital, e.g. at home or in a facility run by midwives. Another advantage of the KiGGS data is the limited number of non-responses. Compared to a percentage of around 15 % of non-responders for the German perinatal survey 2005 55 and of around 20 % for the period 2007–2011 56, the percentage of women for whom there was no information on their smoking behavior during pregnancy was significantly lower, amounting to only 2.6 % in the KiGGS baseline study and 0.3 % in KiGGS Wave 1.

However, the data from the KiGGS studies cannot be directly compared with the data from surveys of pregnant women. This comparison of the birth cohorts of 1996–2002 and of 2003–2012 is based on information provided by the parents of children aged 0 to 6 years. At the time of participating in the KiGGS study, up to six years could have passed since pregnancy, meaning that the responses to questions about smoking behavior during pregnancy could be skewed because of the retrospective nature of the data collection (“recall bias”). Another problem is that the data on maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy is based on self-reporting. It is not possible to exclude responses given based on what is considered socially desirable; this would result in an under-reporting of the actual percentage of women who smoked during pregnancy (“social desirability bias”). However, a recent Swedish study reported that the information provided by participants themselves on their own smoking behavior during pregnancy is valid. In their study, 95 % of women who reported not having smoked during pregnancy were confirmed as non-smokers based on cotinine measurements in maternal serum done at the time of delivery 73. Another limitation of this study is that outcome variables could not be operationalized better in terms of quantity and quality. Pregnant women often stop smoking during pregnancy as soon as they become aware they are pregnant. Some pregnant women attempt to reduce their overall consumption of tobacco. Some women only smoke a cigarette once or twice on very special occasions during pregnancy (New Yearʼs Eve, special celebrations) and otherwise do not smoke at all. Unfortunately the KiGGS data do not allow us to differentiate between these groups.

Finally, it is also important to consider the change in the mode of data collection which occurred between the KiGGS baseline study and KiGGS Wave 1 63. For the baseline study the information on maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy was collected using questionnaires filled out by the study participants themselves; in the subsequent survey, data were collected using computer-based telephone interviews. As interviews sometimes show a stronger tendency towards social desirability bias than written surveys 74, 75, it cannot be excluded that the trend showing a decrease in maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy could be based, at least in part, on a “mode effect”. Whether this mode effect was actually present and how maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy will develop for the birth cohorts after 2012 can be assessed at the earliest in 2017 using the most recent KiGGS data. Written questionnaires asking about maternal smoking behavior during pregnancy will be used again during the fieldwork phase of KiGGS Wave 2, which takes place over a period of three years (2014–2016/2017).

Conclusion

According to the data from KiGGS, the percentage of children aged 0 to 6 years whose mothers smoked during pregnancy has decreased significantly, from 19.9 % for the birth cohorts of 1996–2002 to 12.1 % for the birth cohorts of 2003–2012. It should be noted that there was a change in the mode of data collection used in the KiGGS studies (written questionnaire vs. telephone interview). Children whose mothers were younger than 25 years at the time of their birth and children from socially deprived families have an above-average risk of being exposed prenatally to the harmful effects of the teratogenic substances in tobacco smoke. A two-sided migration background appears to be associated with a lower risk of exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy. From the point of health inequality studies, these results once again confirm that, in terms of health opportunities and the risk of disease in adulthood, social inequality has an impact very early on in life, sometimes even before birth 76. Future target group-specific measures to prevent smoking and to help persons quit smoking should focus more on young and socially deprived women.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.DiFranza J R, Aligne C A, Weitzman M. Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and childrenʼs health. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudenhausen J WHrsg.Rauchen in der Schwangerschaft: Häufigkeit, Folgen und Prävention München: Urban & Vogel; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:S125–S140. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou S, Rosenthal D G, Sherman S. et al. Physical, behavioral, and cognitive effects of prenatal tobacco and postnatal secondhand smoke exposure. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44:219–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mei-Dan E, Walfisch A, Weisz B. et al. The unborn smoker: association between smoking during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:553–558. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaddoe V W, Troe E J, Hofman A. et al. Active and passive maternal smoking during pregnancy and the risks of low birthweight and preterm birth: the Generation R Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:162–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mund M, Louwen F, Klingelhoefer D. et al. Smoking and pregnancy – a review on the first major environmental risk factor of the unborn. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:6485–6499. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10126485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marufu T C, Ahankari A, Coleman T. et al. Maternal smoking and the risk of still birth: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:239. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1552-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum Hrsg.Schutz der Familie vor Tabakrauch. Rote Reihe Tabakprävention und Tabakkontrolle, Band 14 Heidelberg: DKFZ; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voigt M, Briese V, Jorch G. et al. The influence of smoking during pregnancy on fetal growth. Considering daily cigarette consumption and the SGA rate according to length of gestation. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2009;213:194–200. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krentz H, Voigt M, Hesse V. et al. Influence of smoking during pregnancy specified as cigarettes per day on neonatal anthropometric measurements – an analysis of the German Perinatal Survey. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2011;71:663–668. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hackshaw A, Rodeck C, Boniface S. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review based on 173 687 malformed cases and 11.7 million controls. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:589–604. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicoletti D, Appel L D, Siedersberger Neto P. et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and birth defects in children: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30:2491–2529. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00115813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang K, Wang X. Maternal smoking and increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2013;15:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vennemann M M, Findeisen M, Butterfass-Bahloul T. et al. Modifiable risk factors for SIDS in Germany: results of GeSID. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:655–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlaud M, Kleemann W J, Poets C F. et al. Smoking during pregnancy and poor antenatal care: two major preventable risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:959–965. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuman A, Hohmann C, Orsini N. et al. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and asthma in preschool children: a pooled analysis of eight birth cohorts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1037–1043. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0501OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alati R, Al Mamun A, OʼCallaghan M. et al. In utero and postnatal maternal smoking and asthma in adolescence. Epidemiology. 2006;17:138–144. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000198148.02347.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaakkola J J, Gissler M. Maternal smoking in pregnancy, fetal development, and childhood asthma. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:136–140. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haberg S E, Bentdal Y E, London S J. et al. Prenatal and postnatal parental smoking and acute otitis media in early childhood. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stathis S L, OʼCallaghan M, Williams G M. et al. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy is an independent predictor for symptoms of middle ear disease at five yearsʼ postdelivery. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e16. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ino T. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring obesity: meta-analysis. Pediatr Int. 2010;52:94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oken E, Levitan E B, Gillman M W. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:201–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Kries R, Toschke A M, Koletzko B. et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and childhood obesity. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:954–961. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Mamun A, Lawlor D A, Alati R. et al. Does maternal smoking during pregnancy have a direct effect on future offspring obesity? Evidence from a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:317–325. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daseking M, Petermann F, Tischler T. et al. Smoking during pregnancy is a risk factor for executive function deficits in preschool-aged children. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2015;75:64–71. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1383419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitt J, Romanos M. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:1074–1075. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrmann M, King K, Weitzman M. Prenatal tobacco smoke and postnatal secondhand smoke exposure and child neurodevelopment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:184–190. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282f56165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laucht M, Schmidt M. Mütterliches Rauchen in der Schwangerschaft. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2004;152:1286–1294. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams E K, Miller V P, Ernst C. et al. Neonatal health care costs related to smoking during pregnancy. Health Econ. 2002;11:193–206. doi: 10.1002/hec.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voigt M, Straube S, Fusch C. et al. Erhöhung der Frühgeborenenrate durch Rauchen in der Schwangerschaft und daraus resultierende Kosten für die Perinatalmedizin in Deutschland. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2007;211:204–210. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chamberlain C OʼMara-Eves A Oliver S et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy Cochrane Database Syst Rev 201310CD001055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vardavas C, Chatzi L, Patelarou E. et al. Smoking and smoking cessation during early pregnancy and its effect on adverse pregnancy outcomes and fetal growth. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:741–748. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasenack R, Jähne A. Tabakkonsum und Tabakentwöhnung in der Schwangerschaft. SUCHT. 2010;56:183–196. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helmert U, Lang P, Cuelenaere B. Rauchverhalten von Schwangeren und Müttern mit Kleinkindern. Soz Praventivmed. 1998;43:51–58. doi: 10.1007/BF01359224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.GVG Nationales Gesundheitsziel „Tabakkonsum reduzieren“. Veröffentlicht am 19. Mai 2015Online:http://www.gesundheitsziele.delast access: 22.12.2015

- 37.Schneider S, Schütz J. Who smokes during pregnancy? A systematic literature review of population-based surveys conducted in developed countries between 1997 and 2006. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13:138–147. doi: 10.1080/13625180802027993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Euro Peristat Hrsg.European perinatal health report. Health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2010 2013. Online:http://www.europeristat.comlast access: 03.03.2016

- 39.Ekblad M, Gissler M, Korkeila J. et al. Trends and risk groups for smoking during pregnancy in Finland and other Nordic countries. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:544–551. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.AIHW National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit and AIHW Hrsg.National core maternity indicators Canberra: AIHW; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanting C I, van Wouwe J P, van den Burg I. et al. [Smoking during pregnancy: trends between 2001 and 2010] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A5092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohsin M, Bauman A E, Forero R. Socioeconomic correlates and trends in smoking in pregnancy in New South Wales, Australia. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:727–732. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.104232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tong V T, Dietz P M, Morrow B. et al. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy – Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lange S, Probst C, Quere M. et al. Alcohol use, smoking and their co-occurrence during pregnancy among Canadian women, 2003 to 2011/12. Addict Behav. 2015;50:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowry C Scammell KHrsg.Smoking cessation in pregnancy. A call to action. Action on Smoking and Health; 2013Online:http://www.ash.org.uk/pregnancy2013last access: 03.03.2016

- 46.Melchior M, Chollet A, Glangeaud-Freudenthal N. et al. Tobacco and alcohol use in pregnancy in France: the role of migrant status: the nationally representative ELFE study. Addict Behav. 2015;51:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eiríksdóttir V H, Valdimarsdóttir U A, Ásgeirsdóttir T L. et al. Smoking and obesity among pregnant women in Iceland 2001–2010. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:638–643. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Röske K, Lingnau M L, Hannover W. et al. Prävalenz des Rauchens vor und während der Schwangerschaft – populationsbasierte Daten. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:764–768. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1075643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rebhan B, Kohlhuber M, Schwegler U. et al. Rauchen, Alkoholkonsum und koffeinhaltige Getränke vor, während und nach der Schwangerschaft – Ergebnisse aus der Studie „Stillverhalten in Bayern“. Gesundheitswesen. 2009;71:391–398. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1128111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz Sachsen-Anhalt Auswirkungen der Umwelt auf die Gesundheit von Kindern. Schulanfängerstudie Sachsen-Anhalt 1991–2014 2014. Online:http://www.verbraucherschutz.sachsen-anhalt.de/fileadmin/Bibliothek/Politik_und_Verwaltung/MS/Verbraucherschutz/publikationen/fb2/schulanfaengerstudie_internet.pdflast access: 03.03.2016

- 51.Koller D, Lack N, Mielck A. Soziale Unterschiede bei der Inanspruchnahme der Schwangerschafts-Vorsorgeuntersuchungen, beim Rauchen der Mutter während der Schwangerschaft und beim Geburtsgewicht des Neugeborenen. Empirische Analyse auf Basis der Bayerischen Perinatal-Studie. Gesundheitswesen. 2009;71:10–18. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1082310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Kries R. München: StMUGV; 2001. Umwelt und Gesundheit im Kindesalter. Ergebnisse einer Zusatzerhebung im Rahmen der Schuleingangsuntersuchungen 2001/2002 in 6 Gesundheitsämtern. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Gesundheit und Pflege Hrsg.Bayerischer Kindergesundheitsbericht München: stmgp; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergmann R L, Bergmann K E, Schumann S. et al. Rauchen in der Schwangerschaft: Verbreitung, Trend, Risikofaktoren. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2008;212:80–86. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1004749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schneider S, Maul H, Freerksen N. et al. Who smokes during pregnancy? An analysis of the German Perinatal Quality Survey 2005. Public Health. 2008;122:1210–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scholz R, Voigt M, Schneider K T. et al. Analysis of the German perinatal survey of the years 2007–2011 and comparison with data from 1995–1997: maternal characteristics. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2013;73:1247–1251. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1350830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dudenhausen J, Kirschner R, Grunebaum A. Mütterliches Übergewicht und Lebensstil-Faktoren in der Schwangerschaft. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2011;215:167–171. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baron R, Mannien J, de Jonge A. et al. Socio-demographic and lifestyle-related characteristics associated with self-reported any, daily and occasional smoking during pregnancy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reiss K, Breckenkamp J, Borde T. et al. Smoking during pregnancy among Turkish immigrants in Germany-are there associations with acculturation? Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:643–652. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hölling H, Schlack R, Kamtsiuris P. et al. Die KiGGS-Studie. Bundesweit repräsentative Längs- und Querschnittstudie zur Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen im Rahmen des Gesundheitsmonitorings am Robert Koch-Institut. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2012;55:836–842. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamtsiuris P, Lange M, Schaffrath Rosario A. Der Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS): Stichprobendesign, Response und Nonresponse-Analyse. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2007;50:547–556. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurth B M, Kamtsiuris P, Hölling H. et al. The challenge of comprehensively mapping childrenʼs health in a nation-wide health survey: design of the German KiGGS-Study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lange M, Butschalowsky H G, Jentsch F. et al. Die erste KiGGS-Folgebefragung (KiGGS Welle 1). Studiendurchführung, Stichprobendesign und Response. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2014;57:747–761. doi: 10.1007/s00103-014-1973-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lampert T, Kuntz B. KiGGS Study Group . Gesund aufwachsen – Welche Bedeutung kommt dem sozialen Status zu? GBE kompakt. 2015:6. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bergmann K E, Bergmann R L, Ellert U. et al. Perinatale Einflussfaktoren auf die spätere Gesundheit. Ergebnisse des Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS) Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2007;50:670–676. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lampert T, Müters S, Stolzenberg H. et al. Messung des sozioökonomischen Status in der KiGGS-Studie. Erste Folgebefragung (KiGGS Welle 1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2014;57:762–770. doi: 10.1007/s00103-014-1974-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saß A-C, Grüne B, Brettschneider A K. et al. Beteiligung von Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund an Gesundheitssurveys des Robert Koch-Instituts. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2015;58:533–542. doi: 10.1007/s00103-015-2146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robert Koch-Institut Hrsg.Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS) 2003 – 2006: Kinder und Jugendliche mit Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland. Bericht im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit Berlin: RKI; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schenk L, Ellert U, Neuhauser H. Kinder und Jugendliche mit Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland. Methodische Aspekte im Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS) Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2007;50:590–599. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0220-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schaller K, Pötschke-Langer M. Tabakkontrolle in Deutschland und Europa – Erfolge und Defizite. Atemwegs- und Lungenkrankheiten. 2015;41:372–380. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lampert T, Kuntz B. Lengerich: Pabst; 2015. Tabak – Zahlen und Fakten zum Konsum; pp. 72–101. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Statistisches Bundesamt Hrsg.Verteilung der Bevölkerung nach ihrem Rauchverhalten in Prozent. Mikrozensus 1999–2013 (Eigene Auswahl und Aufbereitung der Daten)Online:http://www.gbe-bund.delast access: 22.12.2015

- 73.Mattsson K, Kallen K, Rignell-Hydbom A. et al. Cotinine validation of self-reported smoking during pregnancy in the Swedish Medical Birth Register. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:79–83. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kraus L, Piontek D, Pabst A. et al. Studiendesign und Methodik des Epidemiologischen Suchtsurveys 2012. Sucht. 2013;59:309–320. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hoebel J, von der Lippe E, Lange C. et al. Mode differences in a mixed-mode health interview survey among adults. Arch Public Health. 2014;72:46. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lampert T. Frühe Weichenstellung. Zur Bedeutung der Kindheit und Jugend für die Gesundheit im späteren Leben. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2010;53:486–497. doi: 10.1007/s00103-010-1055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.