Abstract

Ribosome profiling is widely used to study translation in vivo, but not all sequence reads correspond to ribosome-protected RNA. Here, we develop Rfoot, a computational pipeline that analyzes ribosomal profiling data and identifies native, non-ribosomal RNA-protein complexes in the same sample.. We use Rfoot to precisely map RNase-protected regions within small nucleolar RNAs, spliceosomal RNAs, microRNAs, tRNAs, long noncoding (lnc) RNAs, and 3’ˊ untranslated regions of mRNAs in human cells. We show that RNAs of the same class can show differential complex association. Although only a subset of lncRNAs show RNase footprints, many of these have multiple footprints, and the protected regions are evolutionarily conserved, suggestive of biological functions.

Target sites for individual RNA-binding proteins have been identified on a transcriptome scale using CLIP-seq (crosslinking and immunoprecipitation-seq) or PAR-CLIP (photoactivable ribonucleoside-enhanced CLIP) techniques1,2. Two transcriptome-scale methods for more comprehensive identification of RNA-protein interactions in vivo have been described. One approach uses UV crosslinking of cells grown in the presence of 4-thiouridine3,4, but this is limited to short-range interactions of appropriate stereochemistry to permit UV crosslinking. The other approach involves RNase footprinting of RNA crosslinked with formaldehyde5. Both transcriptome-scale approaches map the regions of RNA bound by proteins in the context of the RNA-protein complex, but they do not identify the specific proteins involved. In addition, both methods identify bound regions on a population basis, not at the levels of individual molecules, and hence cannot distinguish between different complexes associated with the same region of RNA.

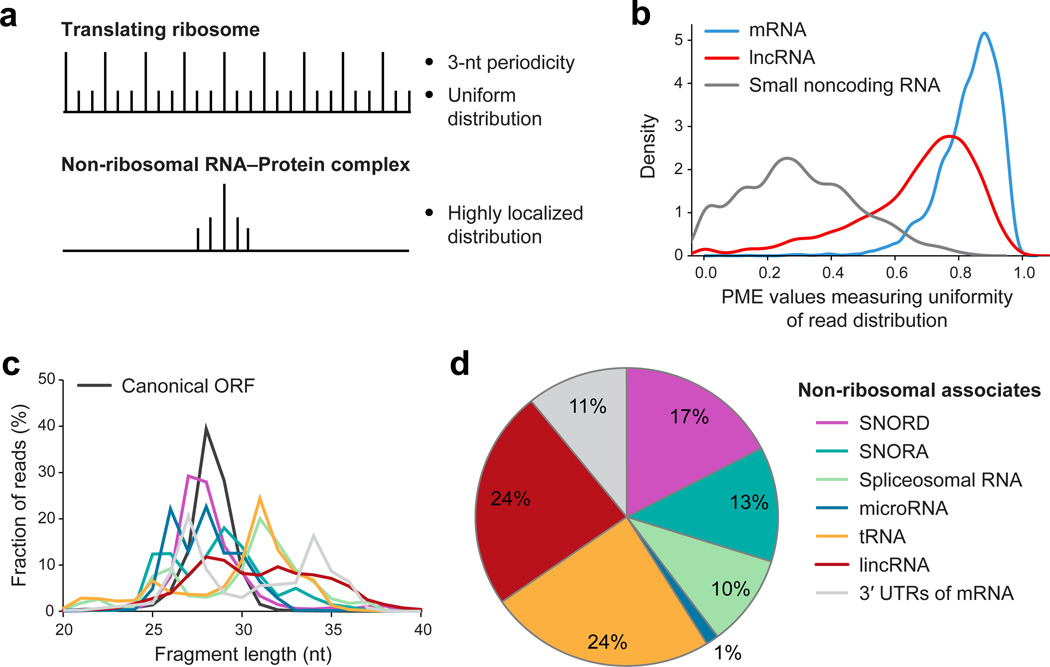

Sequencing of ribosome-protected RNA, known as ribosome profiling, has been used widely to examine translation in vivo6. In this procedure, cell extracts are treated with RNase I to degrade all non-protected RNA, and the resulting material is subjected to velocity sedimentation through sucrose to enrich for material > 7–10S (corresponds to a 100–200 kDa globular protein) while removing degraded RNA and other low-molecular-weight material. In the course of ribosome profiling experiments, we and others noted that many sequencing reads do not correspond to translated regions. Ribosomes are not specifically selected during the biochemical isolation procedure, and therefore non-ribosomal RNA-protein complexes should also be present. In ribosome profiling, sequencing reads correspond to ribosomes that span the entire translated region and show 3-nt periodicity (Fig. 1a). In contrast, sequencing reads corresponding to RNase footprints of non-ribosomal RNA-protein complexes should be highly localized (Fig. 1a,b). Each RNA species has a percentage of maximum entity (PME) value that reflects degree of localization of sequence reads within this RNA (0 represents highly localized and 1 represents uniform distribution across the gene), and different types of RNA–protein complexes have different PME values (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Identifying non-ribosomal protein associated footprints.

(a) Read distribution pattern in translated ORFs and non-ribosomal RNA-protein complexes. (b) Distribution of PME values across transcripts (60nt window). (c) Read fragment length of RNase footprints in types of transcripts. (d) Fraction (in percent) of the various types of RNA-protein complexes.

Based on these considerations, we develop a computational pipeline, Rfoot (Supplementary Code), to systematically identify RNA regions protected by non-ribosomal protein complexes. Specifically, Rfoot searches for protected RNA regions with at least 10 sequencing reads that are highly localized and do not show 3-nt periodicity. Rfoot is distinct from standard peak- detecting methods in ChIP-seq and CLIP-seq analyses that respectively identify DNA or RNA regions bound by proteins. Rfoot considers read distribution patterns and distinguishes between RNA protected by ribosomes, which represent the majority of sequence reads, from RNA protected by non-ribosomal complexes. Unlike analyses of ChIP-seq and CLIP-seq data that require peak detection methods to map bound regions from a population of molecules of varying size with endpoints having varying distances from the protected region, each sequencing read in Rfoot analysis corresponds directly to the fully protected region of an individual RNA-protein complex.

Rfoot analysis of our previous ribosome profiling data7 from two isogenic human cancer cell models (Src-inducible mammary epithelial and Ras-dependent fibroblast;)8 reveals that 11.3% of the sequencing reads correspond to non-ribosomal RNA-protein complexes. Protected RNA regions, and presumably RNA-protein complexes, are observed for virtually all types of cytoplasmic and nuclear RNAs: mRNAs (3’ UTRs); lncRNAs; small nucleolar (sno) RNAs; spliceosomal RNAs; microRNAs; and tRNAs. Detection of a given RNA–protein complex depends on the abundance of the RNA, the fraction of RNA stably bound by proteins throughout the experimental procedure, and the total number of sequencing reads. Although the sequencing depth used here is sufficient to identify RNA–protein complexes from all RNA classes, greater sequencing depth would likely reveal additional complexes involving mRNAs, miRNAs or lncRNAs that are poorly expressed. As expected, different types of RNA–protein complexes protect different lengths of RNAs (Fig. 1c), and the same complexes are observed when translation was inhibited by either cycloheximide or harringtonine.

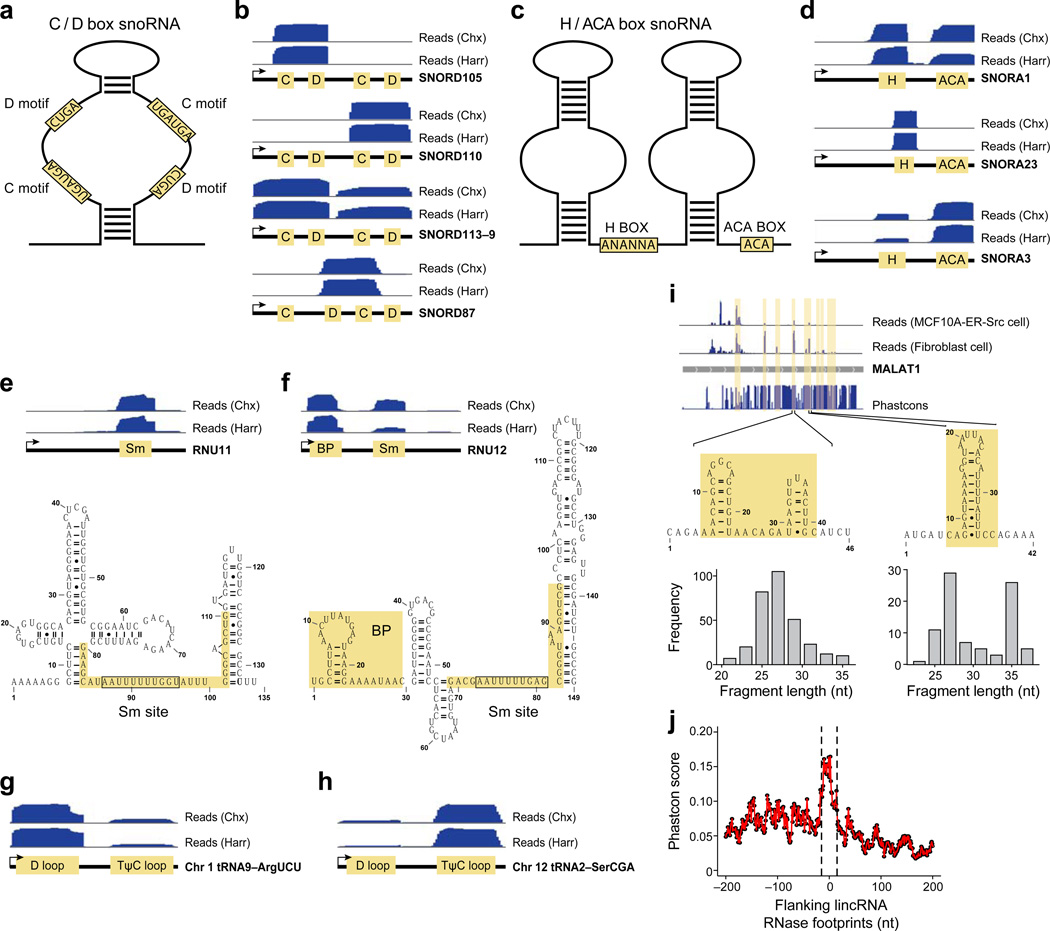

Small nucleolar (sno) RNAs are primarily nuclear, with the C/D box snoRNAs guiding methylation and the H/ACA box class guiding pseudouridylation of other RNAs9. We identified RNase footprints for 112 C/D box RNAs and 68 H/ACA box RNAs (Table S1), which represent almost all expressed snoRNAs. The protected region of C/D type snoRNAs covers the stem loop structure between the C motif (UGAUGA) and D motif (CUGA) (Fig. 2a,b). The region between C/D motifs forms an RNA duplex with the methylation site of the target RNA10, and is bound by C/D ribonucleoproteins9. Notably, although C/D box snoRNAs can form symmetric stem loop structures (Fig. 2a), the protected region covers the left arm of SNORD105, the right arm of SNORD110, and both arms for SNORD113–9, and the middle D and C motifs from different arms of SNORD87 (Fig. 2b). For H/ACA type snoRNAs, the protected regions flank the H box (ANANNA), the single stranded region linking two stem loop structures, and the ACA box located in the tail region (Fig. 2c,d). These motifs are bound by the H/ACA ribonucleoproteins9. Interestingly, although C/D box snoRNAs can form symmetric stem loop structures (Fig. 2a), the protected region covers the left arm of SNORD105, the right arm of SNORD110, and both arms for SNORD113-9, and the middle D and C motifs from different arms of SNORD87 (Fig. 2b). For H/ACA type snoRNAs, the protected regions flank the H box (ANANNA), the single stranded region linking two stem loop structures, and the ACA box located in the tail region (Fig. 2c, d). Reads in SNORA23 are mostly in the H box (Fig. 2d), whereas reads in SNORA3 are more associated with ACA box (Fig. 2d). Thus, it appears that RNA–protein complexes within an individual snoRNA class can have different stabilities or conformations.

Fig. 2. Footprinted regions on various classes of RNA.

(a) Structure of C/D box snoRNAs. (b) Read distribution of the indicated C/D box snoRNAs with respect to the C and D motifs. (c) Structure of H/ACA box snoRNAs. (d) Read distribution of the indicated H/ACA box snoRNAs with respect to the H and ACA motifs. Read distribution in (e) RNU11 and (f) RNU12 spliceosomal RNAs with respect to the indicated motifs and secondary structures. Read distribution in (g) chr1.tRNA9-ArgUCU and (h) chr12.tRNA2-SerCGA tRNAs with respect to the D and TΨC loops. (i) Read distribution in the MALAT1 lncRNA along with protected regions and PhastCon scores based on 44-vertebrate Multiz alignment. Read distributions in the indicated cell types and fragment lengths and RNA structures in two protected regions are shown. The two fragment length peaks in the protected region on the right indicate structurally and/or conformationally distinct RNA-protein complexes. (j) Distribution of mean Phastcon scores around Lnc RNase footprints.

Spliceosomal RNAs associate with spliceosomal proteins to form small nuclear ribonucleic particles (snRNPs) that are critical for RNA splicing11, and we detected RNase footprints for all types of spliceosomal RNAs (Table S1). For RNU11, the protected region is mainly associated with the Sm site (Fig. 2e), a conserved sequence (consensus AUUUGUGG) bound by the SMN complex12. For RNU12, protected regions are observed both for the Sm site and the 5’ hairpin structure (Fig. 2f) that interacts with branch points of pre-mRNA12.

We detected RNase footprints for almost all expressed tRNAs (157 in Table S1). The protected regions are located in the D loop and TΨC loop. The D loop is recognized by aminoacytl-tRNA synthases13, whereas the TΨC loop is important for ribosome binding14. The read distribution between these loops varies among tRNAs. For example, more sequencing reads are observed for the D loop of tRNA9 on chromosome 1 (Figs. 2g,S1a), or the TΨC loop of tRNA2 on chromosome 12 (Figs. 2h,S1b). Thus, as observed for snoRNAs, tRNA–protein complexes can have different stabilities or conformations.

We detected RNase protected regions for 12 miRNAs (Table S1) that cover the mature microRNA (Fig. S2a,b). If one transcript encodes two mature miRNAs (e.g., miR21 and miR21*), sequence reads were observed over both mature miRNAs (Fig. S2c). The RNA– induced silencing complex (RISC) may bind to these regions, but it is unknown why RNase footprints are not detected for most expressed miRNAs.

The fact that mRNAs are associated with ribosomes makes it difficult to identify non-ribosomal RNA–protein complexes that interact with protein-coding or non-canonical translated regions. In this regard, we found 95 protected RNA regions in 3’ UTRs of 69 mRNAs (Table S1). For example, the protected RNA sequence in AMD1 3’ UTR also forms stable hairpin structure (Fig. S3).

Some lncRNAs interact with polycomb proteins, and it has been suggested that these interactions affect chromatin structure and transcription15,16. Although we detect RNase footprints for only 87 (8%) of expressed lncRNAs, this is five times as many footprints as observed for 3’ UTRs, even though the number of nucleotides in 3‘ UTRs is higher than in lincRNAs. Moreover, in this subset of 87 lncRNAs, we identified 208 non-ribosomal binding sites (Table S1), an average of 2.4 footprints/lncRNA. For example, the telomerase component TERC contains 3 non-ribosomal protein-binding sites (Fig. S4a) that cover the H- and CAB-boxes of the ScaRNA domain, and a 5’ single strand region (Fig. S4b), whereas MALAT1 shows several RNase footprints at regions tending to form RNA hairpin structures (Fig. 2i). Notably, one MALAT1 region shows two distinct RNAse footprints as defined by different protected fragment lengths (Fig. 2i) and a similar situation occurs at other lncRNAs (e.g., Fig. S5). Distinct RNase footprints over the same region could reflect completely different or related RNA–protein complexes or alternative conformations of the same complex. In addition, some RNA–protein complexes are cell-type specific (Figs. 2i, S5). Considering all RNase footprints in lncRNAs, PhastCon scores based on 44-vertebrate

Multiz alignment17 of nucleotide sequences reveals that the conservation level is about 2-fold higher than surrounding sequences (Fig. 2j; Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test P-value < 10−19). Taken together, these observations suggest that RNase footprints in lncRNAs may represent RNA-protein complexes that carry out biological functions.

Our experimental method differs from a transcriptome-scale RNase footprinting approach described previously5, and it is advantageous in several respects. First, by avoiding crosslinking, we are able to identify native RNA-protein complexes. Crosslinking can cause artifacts, although it also enables the detection of less stable complexes. Second, whole-cell extracts are subject to a crude purification step that enriches for RNA–protein complexes and removes degraded RNA, thereby eliminating sequence reads corresponding to RNA not associated with proteins. In principle, distinct RNA-protein complexes could be enriched by fractionation based on molecular weight or by immunoprecipitation with an antibody against a specific protein (analogous to CLIP-seq). In addition, factors important for RNase footprints can be identified by comparing cells depleted of an individual factor with their wild-type counterparts. Third, each sequencing read corresponds to a complete protected region for an individual RNA molecule. By examining the size distribution of the protected region of individual RNase footprints, we detected distinct RNA–protein complexes for some footprints of MALAT1 and several other lncRNAs. In contrast, RNase footprints obtained with the previous approach represent averages over many molecules such that distinct RNA-protein complexes cannot be detected.

Our method can analyze reported and future ribosome profiling datasets for RNase footprints on non-ribosomal RNA-protein complexes. In this regard, we performed Rfoot analysis on published ribosomal profiling datasets from mouse cell lines18,19. In accord with our results in human cells, 14.5% of the reads of the sequencing reads correspond to non-ribosomal RNA–protein complexes, and the PME profiles of the mouse (Fig. S6a) and human (Fig. 1b) samples are similar. Furthermore, RNA–protein complexes representing all types of RNA species are identified in these mouse cell lines, and the relative proportion of these types of complexes are roughly comparable to what we observed in human cells (compare Fig. 1d with Fig. S6b). The ability to analyze translation (ribosome footprints) and non- ribosomal RNA–protein complexes in the same sample cannot be done by other methods. Lastly, we note that most of the RNA–protein complexes identified here have not been described previously. As such, our method represents a distinct and complementary approach to identifying RNA–protein complexes on a transcriptome scale.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants to K.S. from the National Institutes of Health (CA 107486). A.R. is a Howard Hughes Investigator.

Footnotes

Accession codes. Experimental data for the identification of RNA-protein complexes is available at GEO (GSE65885), and the Rfoot package can be downloaded from http://www.broadinstitute.org/~zheji/software/Rfoot.0.1.tar.gz

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.J., R.S. A.R., and K.S conceived of and designed experiments, and R.S. performed experiments, Z.J. and H.H. performed the data analysis, and Z.J., R.S. A.R., and K.S co-wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Zhang C, Darnell RB. Mapping in vivo protein-RNA interactions at single-nucleotide resolution from HITS-CLIP data. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hafner M, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baltz AG, et al. The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol. Cell. 2012;46:674–690. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeberg MA, et al. Pervasive and dynamic protein binding sites of the mRNA transcriptome in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-2-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman IM, et al. RNase-mediated protein footprint sequencing reveals protein- binding sites throughout the human transcriptome. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JR, Weissman JS. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science. 2009;324:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1168978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji Z, Song R, Huang H, Regev A, Struhl K. Many lincRNAs are translated and some are likely to express functional proteins. eLife. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08890. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch HA, et al. A transcriptional signature and common gene networks link cancer with lipid metabolism and diverse human diseases. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:348–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matera AG, Terns RM, Terns MP. Non-coding RNAs: lessons from the small nuclear and small nucleolar RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;8:209–220. doi: 10.1038/nrm2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiss-Laszlo Z, Henry Y, Kiss T. Sequence and structural elements of methylation guide snoRNAs essential for site-specific ribose methylation of pre-rRNA. The EMBO journal. 1998;17:797–807. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Will CL, Luhrmann R. Splicesome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:a003707. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell AG, Charette JM, Spencer DF, Gray MW. An early evolutionary origin for the minor spliceosome. Nature. 2006;443:863–866. doi: 10.1038/nature05228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrickson TL. Recognizing the D-loop of transfer RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:13473–13475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251549298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peattie DA, Herr W. Chemical probing of the tRNA-ribosome complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1981;78:2273–2277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell. 2013;152:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siepel A, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eichhorn SW, et al. mRNA destabilization is the dominant effect of mammalian microRNAs by the time substantial repression ensues. Mol. Cell. 2014;56:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz-Munoz MD, et al. The RNA-binding protein HuR is essential for the B cell antibody response. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:415–425. doi: 10.1038/ni.3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.