Abstract

Although immunosuppressive treatments and target concentration intervention (TCI) have significantly contributed to the success of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (alloHCT), there is currently no consensus on the best immunosuppressive strategies. Compared to solid organ transplant, alloHCT is unique because of the potential for bi-directional reactions (i.e., host-versus-graft and graft-versus-host). Postgraft immunosuppression typically includes a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) and a short course of methotrexate after high-dose myeloablative conditioning or a calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil after reduced-intensity conditioning. There are evolving roles for the antithymyocyte globulins (ATG) and sirolimus as postgraft immunosuppression. A review of the pharmacokinetics and TCI of the main postgraft immunosuppressants is presented in this two-part review. All immunosuppressants are characterized by large intra- and interindividual pharmacokinetic variability and by narrow therapeutic indices. It is essential to understand immunosuppressants’ pharmacokinetic properties and how to use them for individualized treatment incorporating TCI to improve outcomes. TCI, which is mandatory for the calcineurin inhibitors and sirolimus, has become an integral part of postgraft immunosuppression. TCI is usually based on trough concentration monitoring, but other approaches include measurement of the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) over the dosing interval or limited sampling schedules with maximum a posteriori Bayesian personalization approaches. Interpretation of pharmacodynamic results is hindered by the prevalence of studies enrolling only a small number of patients, variability in the allogeneic graft source, and variability in postgraft immunosuppression. Given the curative potential of alloHCT, the pharmacodynamics of these immunosuppressives deserves to be explored in depth. The development of sophisticated systems pharmacology models and improved TCI tools are needed to accurately evaluate patients’ exposure to drugs in general and to immunosuppressants in particular. Sequential studies, first without and then with TCI, should be conducted to validate the clinical benefit of TCI in homogenous populations; randomized trials are not feasible due to higher priority research questions in alloHCT. In part I of this article, we review the alloHCT process to facilitate optimal design of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics studies. We also review the pharmacokinetics and TCI of calcineurin inhibitors and methotrexate.

1. Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) is a curative procedure used to treat various nonmalignant and malignant blood disorders and metabolic disorders. The goal of an alloHCT is to cure the patient – termed the host or recipient – of their underlying disease by replacing their hematopoietic cells with cells from a healthy donor. To achieve this cure, a delicate balance must be maintained between the immune system of the host and the donor stem cells (graft) that were infused into the host.1 The transplantation of donor cells that are not genetically identical (i.e., allogeneic) can result in bi-directional immunologic reactions.2 This contrasts with solid organ transplantation, where the graft generally has a limited number of cells with immunologic function and the main concern is preventing rejection of the donor organ by the recipient’s immune system.3 In alloHCT, grafting of cells from one individual to another provokes immunologic reactions involved in engraftment of the donor cells, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), control of a malignancy (termed graft versus tumor, GVT), the development of tolerance, and immune reconstitution.2 These immunologic reactions are influenced by the conditioning regimen (also termed preparative regimen), the type and source of the donor graft, and the postgraft immunosuppressive regimen (Figure 1), all of which are essential components of the alloHCT procedure. The substantive heterogeneity in the conditioning regimen, type of donor graft, and postgraft immunosuppression, combined with variability in the recipient’s characteristics, create challenges to complete adequately powered pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of conditioning regimens have been reviewed elsewhere.4–8 This review focuses upon the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and pharmacogenomics of postgraft immunosuppression in alloHCT recipients. The use of immunosuppressants to treat acute or chronic GVHD is not discussed.

Figure 1. AlloHCT process.

Conditioning schedules vary based on diagnosis. Postgraft immunosuppression taper schedules vary based on the donor graft source, presence of GVHD, and presence of disease relapse.

For postgraft immunosuppression, the goal of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies and personalized dosing through target concentration intervention (TCI) is to improve clinical outcomes by improving efficacy or decreasing toxicity. Improving outcomes can include preventing graft rejection, lowering the rates and/or severity of GVHD, and avoiding excess immunosuppression. Excess immunosuppression should be avoided because of its association with more frequent and severe infectious complications, including bacterial, fungal and viral infections, which contribute to nonrelapse mortality. Focusing upon postgraft immunosuppression in alloHCT recipients, the goals of this review are to 1) provide the reader with an understanding of alloHCT to facilitate informative pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies; 2) review the available relevant pharmacokinetic data and population pharmacokinetic (popPK) models and; 3) review the available pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenomic literature.

2. Understanding alloHCT to conduct pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies

The three main steps in the process of alloHCT are administration of the: (1) conditioning regimen, (2) donor cell infusion, and (3) postgraft immunosuppression (Figure 1). Because alloHCT can treat various nonmalignant and malignant diseases, there is substantive variability in the characteristics of the recipient prior to the alloHCT procedure. Most notable among these factors is recipient age, which can influence clinical outcomes and should be included in pharmacodynamic analyses. For example, thymus-dependent regeneration of CD4+ and CD8+ cells after chemotherapy occurs primarily in children,9,10 and engraftment kinetics after nonmyeloablative (i.e., low dose) conditioning differ between children and adults.11

2.1. Conditioning regimen

Administration of the conditioning regimen is the initial step of the alloHCT procedure. The conditioning regimen is administered before infusion of the donor cells, which occurs on transplant day 0 (Figure 1) and conditioning regimen days are shown by negative numbers (e.g., the conditioning regimen is administered on days −7 to −2). The initial rationale for myeloablative alloHCT was to circumvent dose-limiting myelosuppression with a stem cell infusion, thereby maximizing the potential value of the steep dose-response curve for alkylating agents and radiation,12 suppressing the host immune system, and creating space in the marrow compartment to facilitate engraftment. The goal was to improve cancer cure rates with the increased chemotherapy doses. Unfortunately, myeloablative conditioning is associated with significant morbidity and non-relapse mortality (NRM), wherein the alloHCT recipient dies while having no evidence of their underlying malignancy. This limits the use of myeloablative conditioning to younger patients or those with no or minimal pre-existing comorbidities. To expand the availability of this curative procedure to more patients, over the past 15 years reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens have been developed.13 RIC regimens administer chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy at lower doses than myeloablative regimens with the intent of lowering NRM. Compared to myeloablative conditioning, RIC relies more on the GVT effect, via the immune-mediated assistance from donor lymphocytes for complete eradication of malignant cells.14 A subset of RIC regimens, nonmyeloablative regimens administer the lowest doses of conditioning of all and rely more heavily on the GVT effect provided by minor histocompatibility antigens (mHAs) on leukemic cells.2 Notably, with RIC the host’s cells are still present at the time of donor graft infusion leading to a chimeric state wherein the host and donor cells co-exist within the recipient. Therefore, postgraft immunosuppression must achieve a fine balance between the host and donor cells. Optimal donor chimerism varies by cell type and intensity of the conditioning regimen.15–17 Achieving the optimal donor T-cell chimerism levels early after alloHCT could lower rates of graft rejection and GVHD while maximizing the GVT effect.13

2.2. Infusion of allograft

The infusion of the allogeneic donor stem cells occurs on transplant day 0 (Figure 1), which is at least 24 hours (h) after administration of the last dose of the conditioning regimen. Stem cells, including hematopoietic cells, have the unique capacity to produce daughter cells that retain stem-cell properties. Thus, these cells are self-renewing and provide a lifetime source of blood cells.2 Allogeneic grafts initiate immune reactions related to histocompatibility; the severity of the reaction depends on the degree of incompatibility in the polymorphic class I and class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) cell-surface glycoproteins.2 Notably, recipients of cells from a genetically identical twin sibling, termed a syngeneic graft, do not receive postgraft immunosuppression; because the donor and the patient are genetically identical, GVHD should not be elicited. All other alloHCT recipients, however, are not genetically identical and must receive postgraft immunosuppression. The graft source influences the incidence of the pharmacodynamic endpoints (Table 1) and can impact the pharmacodynamics of the postgraft immunosuppression, as has been demonstrated with mycophenolic acid (MPA, see Part II, Section 2). The roles of graft sources and their effects on engraftment, acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, and immune recovery have been reviewed previously.18–21

Table 1.

Examples of factors other than postgraft immunosuppression that influence pharmacodynamic endpoints in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic trials

| Endpoint | Factors |

|---|---|

| Rejection |

|

| Graft failure |

|

| Acute GVHD | |

| Relapse | |

| Infection |

|

Abbreviations: ATG: antithymocyte globulins; Css: Concentration at steady-state; GVHD: graft-versus-host disease; HLA: human leukocyte antigen; TCD: T-cell depleted; UCB: umbilical cord blood

The ideal donor is a genotypically HLA-matched sibling, as these donors carry the lowest risk of GVHD. A substantive challenge in alloHCT, however, is finding a suitable donor: up to a third of Caucasian patients in need of alloHCT are unable to find such a donor.22 Patients from racial or ethnic minorities face even greater difficulties in finding an appropriate donor.22 There are three alternative graft sources for patients who need an alloHCT but do not have a HLA-matched sibling donor: an unrelated donor, umbilical cord blood (UCB), or a HLA-mismatched haploidentical donor.19,20,23 These alternative graft sources, however, have additional risks or limitations. For example, grafts from HLA-matched unrelated donors are associated with more GVHD than is seen from HLA-matched related donors, although there is some controversy regarding these effects.24

Donor cells also vary by the anatomic site of cell collection. Specifically, cells may be collected from bone marrow, peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC), or UCB. The collection site can influence clinical outcomes21 and thus can affect pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies as well. In unrelated donor grafts, PBSC may reduce the risk of rejection, whereas bone marrow may reduce the risk of chronic GVHD.25 In addition, some donor grafts are manipulated, as in T-cell depletion (TCD), where a graft is rid of alloreactive T-cells either ex vivo or in vitro.26 Notably, recipients of TCD histocompatible grafts generally do not receive postgraft immunosuppression because the volume of donor T-cells infused into the recipient is usually insufficient to elicit a significant graft-versus-host reaction.27,28

When interpreting pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies of postgraft immunosuppression, attention must be paid to the HLA typing methods. There have been technologic improvements in HLA typing, with great improvements in high resolution allele typing for unrelated donor alloHCT.29,30 The impact of HLA allelic mismatches upon pharmacodynamic endpoints differs based on graft source.31,32 Beyond HLA matching, minor antigens encoded by genes on the Y chromosome account for a higher GHVD incidence and a lower relapse rate among male recipients of female donor grafts compared to male recipients of male donor grafts.2

2.3. Postgraft immunosuppression

The third step of alloHCT is the administration of postgraft immunosuppression. The primary goal of postgraft immunosuppression is to ensure engraftment and prevent the development of GVHD while maintaining GVT. Immunosuppressants inhibit and minimize the activity of donor T-cells. Immunosuppressive therapy is most often initiated either a few days prior to or just after completion of the infusion of donor stem cells on day 0.

The type of and compliance with the postgraft immunosuppression influence GVHD risk.3 Postgraft immunosuppression varies between myeloablative and RIC regimens (Table 2). Since myeloablative conditioning has been available for longer, there are more data from patients receiving myeloablative alloHCT than from those receiving RIC alloHCT. Initial regimens included single-drug therapy using cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, or cyclosporine.33–35 In most patient populations, randomized clinical trials after myeloablative conditioning have documented the superiority of combination postgraft immunosuppression compared to monotherapy with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, or cyclosporine.35–38

Table 2.

| Immunosuppressants | Recommended Dosing |

|---|---|

| After myeloablative conditioning | |

| Cyclosporine/methotre xate35,38 |

|

| Tacrolimus/methotrexate40 |

|

| Rabbit ATG (Thymoglobulin®) | 2.5 mg/kg on days −3, −2, −1 |

| After RIC | |

| Cyclosporine/MMF |

|

| Tacrolimus/MMF |

|

| TCI | |

| Cyclosporine |

|

| Tacrolimus | Not described |

| Methotrexate | Not described |

Examples provided represent commonly used doses for adults only.

Abbreviations: ATG: antithymocyte globulins; HLA: human leukocyte antigen; IV: intravenous(ly); MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; PO: oral(ly); Q12h: every 12 hours, Q8h: every eight hours; RIC: reduced intensity conditioning

A variety of two- and three-drug combination immunosuppressive regimens have been used for prophylaxis against GVHD. Cyclosporine or tacrolimus, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) are the agents most commonly incorporated into combination immunosuppressive regimens. The most commonly used regimen – termed the Seattle regimen – is a combination of methotrexate and a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI), either cyclosporine or tacrolimus,35,39–42 but there is no national consensus with regard to the most effective regimen. Several studies have compared three-drug to two-drug immunosuppression schemas. The incidence of acute GVHD is similar or lower with three-drug regimens, but infectious complications are higher and overall survival is similar to survival with two-drug regimens.43,44 After RIC regimens, postgraft immunosuppression varies more widely by transplant center but most often consists of a combination of a CNI and MMF, a pairing that was also developed in Seattle.17,45 In alloHCT, postgraft immunosuppression may eventually be discontinued because the immunologically active tissues of the host and donor become tolerant of one another over time and no longer recognize each other as foreign. Therefore, in alloHCT recipients without GVHD, immunosuppressive therapy is slowly tapered and generally discontinued over 6 months.45 This is in contrast to solid organ transplant recipients, where immunosuppressive therapy usually must be continued for a recipient’s entire life.

3. Pharmacodynamic endpoints

3.1. Rejection

Acceptance of the donor cells, termed engraftment, is critical to the success of alloHCT. Graft rejection after alloHCT can manifest as either a lack of initial engraftment or development of pancytopenia and marrow aplasia after initial engraftment.3 Rejection, drug toxicity, sepsis, and certain viral infections can all cause graft failure.3 An absence of donor cells and the presence of recipient T-cells are key findings to support the diagnosis of rejection in a patient with graft failure.3 Because of the durable persistence of donor cells, however, rejection is unlikely, even when recipient T-cells can be detected.3

In patients receiving a RIC regimen, the risk of rejection can be influenced by donor chimerism. After administration of the RIC, the recipient’s immune system is not completely ablated such that both the donor and recipient cells are circulating within the patient. The development of quantitative chimerism monitoring, specifically evaluating the donor chimerism, provides a critical tool for patient prognosis and data on which to base clinical intervention in patients receiving RIC.46,47 The longitudinal changes in donor chimerism, termed “engraftment kinetics,” are influenced by several factors, including the type of alloHCT conditioning, stem cell source, and the intensity of postgraft immunosuppression.46,48 Donor chimerism is evaluated in different cell types (e.g., T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, granulocytes) and there is a trend for more frequent monitoring of chimerism after infusion of the donor graft.15,46,49–51 Quantitative evaluation of chimerism most often uses a polymorphic system of DNA biomarkers, such as short tandem repeats (STRs).47,52–54 STRs are short sequences of nucleotides that are variably and randomly repeated throughout the genome. Using this quantitative approach, it is possible to assess the full range of donor chimerism values, from 0 to 100%.

3.2. Graft versus host disease

GVHD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality for alloHCT recipients.20 Thus, its prevention is ideal. GVHD is initiated by donor T-cells recognizing recipient major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I alloantigens, class II alloantigens, and minor mHAs on recipient antigen presenting cells that persist after the pretransplant conditioning regimen.3 Despite administration of postgraft immunosuppression, 60% of alloHCT recipients develop acute GVHD in the first 100 days post-transplant, and up to half develop chronic GVHD26

GVHD is categorized as acute or chronic based on clinical manifestations. Acute GVHD is a clinical syndrome affecting primarily the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Acute GVHD is staged by the number and extent of organs affected and classified as one of four grades (I-IV) depending on the degree or state of involvement of the affected sites.55–57 In contrast, chronic GVHD can affect almost any organ system and closely resembles several autoimmune diseases. Immune-mediated destruction of tissues, a hallmark of GVHD, disrupts the integrity of protective mucosal barriers and provides an environment that favors the establishment of opportunistic infections. The biological mechanisms leading to chronic GVHD are not as well understood as those leading to acute GVHD, and the relationship between acute and chronic GVHD is unclear3 Although acute GVHD is a risk factor for chronic GVHD, not all cases of acute GVHD evolve into chronic GVHD, and chronic GVHD can develop in the absence of any prior overt acute GVHD.3 Chronic GVHD is the most frequent late complication of alloHCT and it occurs in 30 – 70% of long-term survivors of myeloablative alloHCT.58,59 In addition, chronic GVHD is the major cause of NRM and morbidity.60–62

3.3. Graft versus tumor (GVT)

In alloHCT, donor lymphocytes can help eliminate malignant cells that survive the conditioning regimens. Without question, GVHD and GVT continue to be tightly linked in alloHCT recipients.14,63,64 Our present understanding is that the donor T-cells react with cells from the HLA-matched, genetically non-identical recipient. Donor T-cells specifically target the host’s non-hematopoietic tissue, causing GVHD, and the hematologic malignancy, causing a GVT response.65,66 Work is ongoing to segregate these polymorphic differences to allow donor T-cells react with host leukemic cells without damaging the non-hematopoietic tissues.66

4. Unique considerations for pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies in alloHCT

There are unique considerations for conducting pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies of immunosuppression in alloHCT recipients compared to those conducted for FDA approval of a new drug or in solid organ transplantation. The first consideration is the substantive variability in alloHCT clinical practice, both overall67 and specifically in postgraft immunosuppression.68 Most alloHCT recipients will eventually discontinue their immunosuppression and maintain a state of immune tolerance (see Section 2.3).68 There is, however, substantive variation in when immunosuppression is tapered, which agent is tapered first, how quickly these changes are made, and the strategy underlying the planned immunosuppression taper.68 This variation may influence the development of acute GVHD or chronic GVHD, which are often pharmacodynamic endpoints in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies. Fortunately, efforts are underway to more rigorously study the effects of this variability in clinical practice68 and to create international networks to develop worldwide priorities to address alloHCT issues.69

The second consideration in conducting pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies of postgraft immunosuppression is the subjective assessment of both acute GVHD and chronic GVHD. Evaluating GVHD as a pharmacokinetic covariate is particularly challenging because assessing its severity involves subjective judgments in the interpretation of medical records and at the bedside.70 The challenges present particular difficulties for multicenter or retrospective studies.

The role of covariates on the pharmacokinetics of immunosuppressed alloHCT recipients is a third consideration for pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies in these patients.. Myeloablative conditioning regimens can only be administered to patients healthy enough to tolerate these regimens’ considerable toxicity. Therefore, the myeloablative alloHCT population has minimal variability in renal or liver function, which may limit covariate analyses. In addition, the vast majority of alloHCT pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies are single-institution studies that often have small sample sizes, which can further limit covariate analyses and also the extent to which study results can be generalized.

The fourth consideration is the potential role drug-drug interactions (DDI) in alloHCT recipients.71 In alloHCT, nearly all patients must contend with polypharmacy, and DDI are often unpredictable and variable.72 These DDI exist between multiple immunosuppressants and supportive care medications, such as antifungal agents. Only recently has the magnitude of potential DDI of postgraft immunosuppression in alloHCT recipients been published.73 Much of what is currently known about potential DDI is extrapolated from studies conducted in the setting of solid organ transplantation.74–76 Examples of potential DDI in alloHCT are those resulting from concomitant antibiotics or antifungals, which are needed because of the immunosuppression in alloHCT recipients.77 The effect of antibiotics upon enterohepatic recirculation of MPA is difficult to study because of inconsistent documentation regarding the precise initiation and discontinuation of antibiotics relative to the days of MPA PK sampling.78 Furthermore, since MPA TCI has yet to be widely adopted, an antibiotic – MPA interaction is likely to be missed. Another example is the DDI between azole antifungals and CNIs, which can be managed through TCI.71 The azoles have variable cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 inhibition and potentially also affect CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and p-glycoprotein (PgP). The risk of deleterious DDI led to a change in the primary endpoint of prophylactic antifungal trials from invasive fungal infections to failure-free survival.79 Failure-free survival provides a net assessment of the efficacy of the antifungal in preventing an invasive fungal infection and any negative effect of mortality from adverse events, some of which arise from deleterious DDI.79 Although these azole – immunosuppressive DDIs are well known, their management can be challenging and could benefit from improved PK/PD modeling.

5. Literature search methods

Extensive literature searches in PubMed were conducted with the immunosuppressants’ generic names and “allogeneic transplant*” (.e.g., cyclosporine AND allogeneic transplant* for cyclosporine manuscripts). Subsequent literature search terms were specified to the relevant topic – such as ‘obesity AND cyclosporine AND allogeneic.’ Additional references were added as needed based on the authors’ literature review. The tables in both Part I and Part II were predominantly constructed by JSM and MJB, with confirmation of data by the other author.

6. Calcineurin inhibitors

The CNIs, cyclosporine and tacrolimus, are an essential part of postgraft immunosuppression for alloHCT after myeloablative conditioning or RIC (Section 2.3). The CNIs are typically used in combination with methotrexate after myeloablative conditioning or with MMF after RIC (Table 2). The section below describes both CNIs together because of their similar mechanisms of action and similar pharmacokinetic characteristics.80 Clinically, however, there has been considerable discussion regarding whether cyclosporine or tacrolimus is the optimal CNI; this debate has been comprehensively reviewed previously.81,82

6.1. Pharmacokinetics

6.1.1. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion

To choose the appropriate target trough concentration for an individual patient, the pharmacodynamic association of CNI concentrations with clinical outcomes must be interpreted cautiously with respect to the alloHCT characteristics (detailed in Section 2), the methods and timing of pharmacokinetic sampling,83 the and the analytical method used for quantification of the CNI concentrations. Artificially high cyclosporine concentrations may be due to desorption of cyclosporine from the material of central venous catheters.84 Close attention should be paid to the analytical method to quantify cyclosporine. The monoclonal and polyclonal immunoassay methods have cross-reactivity with cyclosporine metabolites and will provide different results than the preferred HPLC method.85 More recent immunoassays, such as antibody-conjugated magnetic immunoassay (ACMIA), have no significant inter-method bias compared to LC-MS/MS of whole blood concentrations of cyclosporine or tacrolimus in pediatric transplant patients.86

When interpreting pharmacokinetic data from cyclosporine, caution should be paid to the analytical method used. The monoclonal and polyclonal antibody assays cross-react with and measure varying amounts of metabolites in addition to the parent compound.85 The immunoassay methods can overestimate cyclosporine and tacrolimus drug concentrations, because of cross-reactivity with other drugs and/or chemical moieties on biomolecules.87–89 The alternative assay, which uses HPLC with mass spectrometry (LC/MS), is completely specific for the parent compound.

Third, there are limited data to suggest that there is a correlation between CNI concentrations and clinical outcomes. The results from these studies suggest that there may be a complex relationship between dose, blood concentrations, and the occurrence of GVHD. Interpretation of the pharmacodynamic studies is also complicated by small heterogeneous samples and insufficient details regarding when the trough samples were drawn relative to the administration time.90 Thus, it is not surprising that contradictory results have been found.

Both cyclosporine and tacrolimus share the same pathways for absorption, metabolism, distribution, and excretion. Both are highly lipophilic, which contributes to their highly variable absorption and extensive metabolism.80 Oral bioavailability (F) of both drugs is generally poor with mean values around 25%, but wide variation in oral bioavailability is seen between individuals using these two drugs.91 Both cyclosporine and tacrolimus bind extensively to erythrocytes, and only unbound drug is capable of entering lymphocytes and exerting its main immunosuppressive effects.91 The oral bioavailability and the systemic clearance of both drugs are mainly influenced by CYP 3A4 and 3A5 and the efflux pump PgP, as well as multigrug resistance 1 (MDR1) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–binding cassette (ABC) subfamily B member 1 (ABCB1). Both CYP3A4 and 3A5, along with PgP, are expressed in the gastrointestinal tract (affecting oral bioavailability) and in the liver (affecting both oral bioavailability and systemic clearance).80,92,93 After either intravenous or oral administration, less than 1%94 of the administered parent drug is excreted unchanged in either the urine or feces, with the vast majority of metabolites (>95%) appearing in the feces.80 This is mediated by active excretion of these metabolites into the bile or directly into the gut lumen.80 For cyclosporine, ~25 metabolites are formed; the major metabolites found in blood are AM1, AM9 and AM4N.91 The immunosuppressive activity of these metabolites varies, but all metabolites studied thus far have reduced activity compared with cyclosporine.91 AM1 has the highest immunosuppressive activity, with its reported activity varying from 20% to as high as 80% as active as cyclosporine.91 Up to 15 metabolites of tacrolimus may be formed. The most prevalent metabolite, 13-O-demethyl-tacrolimus is approximately one-tenth as active as tacrolimus.91 A minor metabolite, 31-O-demethyltacrolimus, has immunosuppressive activity comparable with tacrolimus.91 The remaining metabolites have weak pharmacological activity.91

After myeloablative conditioning regimens, the CNIs usually are administered intravenously until gastrointestinal toxicity (e.g., chemotherapy-induced emesis, diarrhea) from the conditioning regimen has resolved.35 Gastrointestinal effects of the conditioning regimen and GVHD affect the oral absorption of microemulsion cyclosporine and may result in inconsistent blood concentrations.95 Older pharmacokinetic data studied an earlier formulation of cyclosporine, Sandimmune®, which has an intravenous to oral ratio of 1:4.85 With the newer microemulsion formulations a ratio of 1:296 or 1:3 is used when converting from intravenous to oral dosing. Tacrolimus has a ratio of 1:4 when converting from intravenous to oral dosing.85 Different conversion ratios for intravenous to oral regimens may be used when patients are receiving concomitant medications that affect CYP3A4 or PgP, such as itraconazole.

The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) of both cyclosporine and tacrolimus are higher in the morning than the afternoon.94 Seasonal variation is also of concern, as it has recently been reported that duodenal CYP3A4 mRNA is significantly higher between April and September than between October and March.97 The cyclosporine population clearance in alloHCT patients ranges from 8.498 to 22.399 L/h for a 70kg adult. In alloHCT, tacrolimus clearance ranges from 71100 to 125101,102 mL/h × kg. Tacrolimus has a volume of distribution of 1.67 L/kg, oral bioavailability of 31–49%, and 18.2 h half-life.103

6.1.2. Pharmacogenomics

Genetic polymorphisms of CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and PgP may impact the pharmacokinetics of CNIs.104 Although there is a paucity of such data from alloHCT recipients, recent data indicates that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of CYP3A5 were associated with the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine105,106 or tacrolimus107 and that ABCB1 polymorphisms were associated with cyclosporine pharmacokinetics.106

6.1.3. Drug-drug interactions

As noted in Section 4, much of what is currently known about potential DDI in alloHCT is extrapolated from studies conducted in the setting of solid organ transplantation.74–76 Examples of potential DDI in alloHCT are those resulting from concomitant calcium channel blockers, imatinib, antibiotics, or antifungals, which are needed because of the immunosuppression of alloHCT recipients.71,108,109 Because of routine TCI of trough or shortly pre-dose concentrations of the CNI, these results can be used to identify a DDI and appropriately change the dose of the CNI. For example, the DDI between azole antifungals and CNIs has long been recognized110,111 and can be managed through TCI.71 The azoles have variable CYP3A4 inhibition and potentially also affect CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and PgP.71 The risk of deleterious DDI led to a change in the primary endpoint of prophylactic antifungal trials from invasive fungal infections to failure-free survival.79 Failure-free survival provides a net assessment of the efficacy of the antifungal in preventing an invasive fungal infection and any negative effect of mortality from adverse events, some of which arise from deleterious DDI.79 Although these azole – immunosuppression DDI are well known, their management can be variable and could benefit from improved pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling. Notably, recipients of nonmyeloablative alloHCT have an increased burden of comorbidities, potentially increasing the number of concomitant medications and potential DDI affecting the pharmacokinetics of the CNI.

6.1.4. Special populations

6.1.4.1. Renal or hepatic impairment

The impact of renal or hepatic impairment upon the pharmacokinetics of CNIs is minimally characterized. A previous population study in 122 adult alloHCT patients found that bilirubin, serum creatinine, GVHD, and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome significantly influenced tacrolimus clearance.100,102 In 22 pediatric alloHCT recipients, tacrolimus clearance decreased with increasing serum creatinine.102 Notably, recent data suggested that diabetes, a common cause of renal dysfunction, alters tacrolimus metabolism, although further studies are needed.112

6.1.4.2. Pediatric

With intravenous cyclosporine, age was a covariate for clearance in 27 alloHCT recipients aged 0.9 – 20 years.113 Children have a more rapid intravenous tacrolimus clearance than adults,101,114 and careful TCI in the first 2 weeks after allograft infusion has been recommended.101 In 22 pediatric alloHCT patients, Wallin et al. reported the following intravenous tacrolimus parameters: typical clearance was 106 mL/h×kg0.75, typical distribution volume was 3.71 L/kg, and typical oral bioavailability was 15.7%.102 Tacrolimus clearance decreased with increasing serum creatinine, and oral bioavailability decreased with post-graft infusion day.102

6.1.4.3. Obese

Obesity has no significant effect upon the volume of distribution or clearance of cyclosporine.115 The American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT) guidelines do not address cyclosporine or tacrolimus dosing in obese patients.116 The current dosing and TCI methods for obese children appear sufficient since no difference in survival was observed in 3,687 pediatric alloHCT recipients of differing body mass index (BMI) with various hematologic malignancies.117 Unfortunately, the dosing methods were not specified in this Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) dataset. However, the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act – Pediatric Trials Network Administrative Core Committee’s systemic review identified one study of cyclosporine pharmacokinetics in obese children.118 In adolescent renal transplant recipients, cyclosporine doses after correction for body weight, bone mass index, or body surface area (BSA) were significantly lower in patients who were obese (BMI >95th percentile) or overweight (BMI >85th percentile) compared to controls (BMI <95th percentile or <85th percentile, respectively).119 Despite this difference in doses, the obese and overweight adolescents achieved similar trough and 2 h post-dose cyclosporine concentrations compared to the controls.119

6.1.5. Pharmacodynamic measurements

Various biomarkers have been evaluated to measure the pharmacodynamic response to CNIs. While methods to assess calcineurin activity have been available for over 25 years,120 the two studies in alloHCT recipients have yielded conflicting findings regarding the association between calcineurin activity and acute GVHD.121,122 There are numerous limitations to calcineurin activity quantitation. These limitations have been recently overcome, but calcineurin activity has yet to be associated with clinical outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients.123,124 Pai et al. characterized calcineurin activities in mononuclear cells isolated from 12 healthy volunteers and 62 alloHCT recipients, 33 of whom were administered cyclosporine and 29 of whom were not.122 Calcineurin activity was significantly suppressed by cyclosporine administration. Among patients administered cyclosporine, calcineurin activity was lower in those with acute GVHD compared to those without acute GVHD. Calcineurin activity was comparable among patients with or without chronic GVHD. The lower calcineurin activity of patients with acute GVHD suggests that cyclosporine-resistant GVHD did not result from inadequate suppression of calcineurin activity. Likewise, if calcineurin inhibition is the only physiologic target of cyclosporine, increased cyclosporine doses or use of an alternative CNI would not ameliorate GVHD. Subsequently, Sanquer et al. evaluated the association of calcineurin activity during the first 2 months after alloHCT graft infusion with acute GVHD in 31 alloHCT recipients treated with cyclosporine prophylaxis (2 mg/kg/day) and methotrexate (on days +1, +3, and +6).121 Calcineurin activity was measured before alloHCT and then once weekly for at least 2 months. In contrast to the prior findings, calcineurin activity was significantly increased in the 18 patients with GVHD compared with the 13 who did not develop GVHD. Although this group concluded that calcineurin activity was a promising test to predict acute GVHD, no further studies have been reported.

More recently, methods have been developed to evaluate the inhibitory effect of the CNIs upon interleukin 2 (IL2) mRNA expression both in vitro and ex vivo. These methods have been developed using samples obtained from healthy volunteers125 and only recently been applied to renal transplant patients.126 Data regarding IL2 mRNA expression after CNI administration in alloHCT recipients was not found. Research is also ongoing with quanitifying the relationship between cyclosporine trough whole blood concentrations and neutrophil response in children with severe aplastic anemia, with neutrophil response being a biomarker of response.127

6.2. TCI

6.2.1. Recent pharmacodynamic studies

As noted earlier (see Section 2.3), the addition of cyclosporine to GVHD prophylaxis – known as the Seattle regimen (i.e., cyclosporine/methotrexate regimen35) – substantively improved outcomes after alloHCT. TCI was rapidly accepted to dose cyclosporine based on trough concentrations in whole blood and was subsequently implemented for tacrolimus dosing; TCI of CNIs is now widely accepted clinically.128–130 The principal adverse effects associated with CNIs are neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, magnesium wasting, gastrointestinal disturbances, infections, and malignancy.91 The dose of cyclosporine or tacrolimus is adjusted based on trough drug concentrations and the serum creatinine concentration. Furthermore, CNIs have substantial DDI liability, which is often mitigated by careful trough monitoring (see Section 6.1.2).

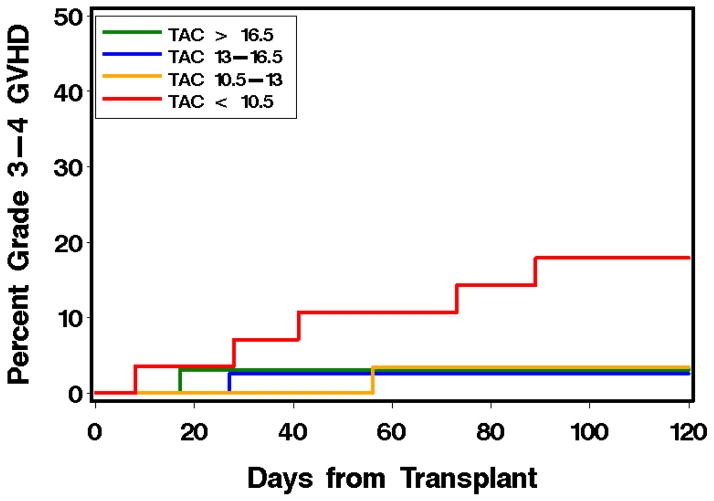

To choose the appropriate target trough concentration for an individual patient, the pharmacodynamic association of CNI concentrations with clinical outcomes must be interpreted cautiously with respect to the alloHCT characteristics (detailed in Section 2) and with respect to the pharmacokinetic sampling techniques83,84 and the quantification method. The historic pharmacodynamic data of cyclosporine with outcomes have been reviewed previously;115 the results of pharmacodynamic studies reported within the past decade are summarized in Table 3. 131 The Seattle group reported the largest pharmacodynamic study in alloHCT, analyzing data from more than 1000 patients with hematological malignancies who had alloHCT from a HLA-matched related or unrelated donors over a 10-year time period.131 After myeloablative conditioning, higher CNI concentrations were not associated with lower risks of acute or chronic GVHD (Figure 2). In contrast, in a study of over 400 patients undergoing nonmyeloablative alloHCT, higher cyclosporine concentrations were associated with decreased risks of grades II–IV and III–IV acute GVHD, NRM, and overall mortality. Cyclosporine concentrations were not associated with risks of chronic GVHD and recurrent malignancy after nonmyeloablative alloHCT. Among patients given tacrolimus after nonmyeloablative alloHCT, a similar trend of CNI-associated GVHD protection was observed. Importantly, higher cyclosporine concentrations were not associated with an increased risk of renal dysfunction. Thus, higher cyclosporine concentrations relatively early (i.e., week 2 after graft infusion) after nonmyeloablative alloHCT appear to confer protection against acute GVHD that translates into reduced risks of non-relapse and overall mortality. Specifically, a cyclosporine trough concentration above 345 ng/mL (LC/MS-MS) provided incremental protection against grades II–IV and grades III–IV acute GVHD in patients receiving cyclosporine (intravenously or orally) every 12 h. There are, however, some limitations of this retrospective analysis that were noted by the authors and in an accompanying editorial.132 A large prospective trial showed only a trend toward an association between low cyclosporine concentrations and increased GVHD risk, whereas no association was found between tacrolimus concentrations and GVHD risk.133 Furthermore the significance of lower cyclosporine concentrations was predominantly based on the worse outcomes in the lower quartile of the population.131 Notably, in patients given tacrolimus, higher week 2 mean levels were correlated with the risk of grades III–IV, but not grades II–IV, acute GVHD. Also, it is not clear why a pharmacodynamic association was found only after nonmyeloablative conditioning; this is perhaps related to the use of MMF instead of methotrexate. The results of studies in smaller alloHCT populations are also summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Recent CNI – either cyclosporine or tacrolimus – pharmacodynamic studies in alloHCT patients receiving a CNI as postgraft immunosuppressiona

| Citation | Study population | IS | CNI sampling | Pharmacodynamics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rogosheske et al. 2014140 | N=337 Ages 15–74 yr Regimens MA: N=118, CY/TBI or BU NMA: N=219 CY/FLU/TBI Donors Related: N=128 URD: N=209 Graft sources PBSC: N=128 Double UCB: N=209 |

CNI All: CSA Starting Dose All: CSA 5 mg/kg IV BID Starting Day All: day −3 Other IS MA related: MTX 15 mg/m2 day +1, 10 mg/m2 day +3, +6, +11 MA UCB: MMF 2–3 g/day day −3 to +30 NMA: MMF 2–3 g/day day −3 to +30 |

Time points Trough concentrations Assay HPLC with whole blood Frequency CSA trough monitored thrice weekly through day +7 then once weekly or 48 h after making a dose Target concentration All CSA: trough 200–400 ng/mL CSA dose increased by at least 25% if day −1 trough <200 ng/mL |

Data analysis

Renal Toxicity

Acute GVHD

Chronic GVHD

NRM & overall mortality

|

| Ram et al. 2012131 | N=1181 Ages 18–74 yr Regimens MA: N=774, CY/TBI or BU/CY NMA: N=407, FLU/TBI Donors Related: 54% URD: 46% Graft sources Marrow: 9% PBSC : 91% |

CNI CSA or TAC Starting dose MA: N=451 CSA, 3 mg/kg/day BID; or N= 323 TAC, 0.03 mg/kg/day continuous IV infusion, changed to PO when tolerated NMA: N=280 CSA, 5 – 6.25 mg/kg PO BID; or N=127 TAC, 0.06 mg/kg PO BID Starting day<br1>MA: day −1 NMA: day −3 Other IS MA: MTX 15 mg/m2 day +1, 10 mg/m2 day +3, +6, +11 NMA: MMF 15 mg/kg/day BID or TID |

Time points Trough concentrations Assay CSA: monoclonal or polyclonal antibody or HPLC with whole blood; correction factor of 0.80 applied to adjust all CSA concentrations measured with antibody assay to the HPLC values. TAC: IMx with whole blood Frequency Twice weekly Target concentration All CSA: 200–500 ng/mL All TAC: 5–20 ng/mL |

Data analysis

Renal toxicity

Acute GVHD

Chronic GVHD

NRM & overall mortality

|

| Gerard et al., 2011179 | N=61 Ages 0.5 – 17 yr Regimen Not available Donors Related: 52.5% Unrelated: 47.5 % Graft sources Marrow: N=61 |

CNI CSA N=30 as continuous infusion, N=31 as intermittent infusion, twice daily (2 h infusion every 12 h) Starting dose Not available Starting day Not available Other IS Not available; authors note MTX was not administered |

Time points Periodic monitoring Assay CSA: EMIT of whole blood Frequency Periodic Target concentration Continuous infusion: Css 200 ng/mL (malignant disease) or 280 ng/mL (non-malignant disease). Intermittent infusion: trough 110 ng/mL (malignant disease) or 130 ng/mL (non-malignant disease). |

Data analysis

Renal toxicity

Acute GVHD

Chronic GVHD

NRM & overall mortality

|

| Willemze et al. 2010152 | N=91 Ages 1–17 yr Regimen Not available Donors Related: N=62, all siblings with 10/10 allele match URD: N=29, all with 9/10 allele match Graft source Marrow: N=83 PBSC: N=6 UCB: N=2 |

CNI CSA Starting dose CSA: 2 mg/kg/day IV divided over two doses Starting dose CSA: Between day −3 and day −1. Other IS MTX 10mg/m2 on days +1, +3, and +6, some patients also received MX on day +11 |

Time point Trough Assay RIA or fluorescence polarization immunoassay Frequency Weekly Target concentration Not provided. If considered necessary by the treating physician, dose adjustments were made on the basis of trough concentration measurements. |

Data analysis

Renal toxicity

Acute GVHD

Chronic GVHD

NRM & overall mortality

Other

|

| Malard et al. 2010180 | N=85 Ages 18–67 yr Regimens MA: N=24, CY/TBI or BU/CY RIC: N=61, varied Donors Related: N=37 Unrelated: N=48 Graft sources Marrow: N=19 PBSC: N=66 |

CNI CSA Starting dose 3 mg/kg/day continuous IV infusion, changed to PO when tolerated Starting day All: day −3 or −2 Other IS MA: N=22, MTX 15 mg/m2 day +1, 10 mg/m2 day +3, +6 RIC : N=31 CSA alone or N=22 MMF 1–2g/day |

Time points Trough concentrations collected early in the morning Assay Radioimmunoassay with whole blood Frequency Thrice weekly during IV, at least once weekly during oral Target concentration All CSA: 150–250 ng/mL and to prevent renal dysfunction |

Data analysis

Renal Toxicity

Acute GVHD

Chronic GVHD

NRM & overall mortality

|

| Punnett et al. 2007181,182 | N=87 Ages 0.3–18 yr Regimens MA: varied Donors Related: N=38, sibling or parent; URD: N=49 Graft sources Marrow: N=84 PBSC: N=2 UCB: N=1 |

CNI CSA Starting dose All: 3mg/kg/day IV BID, changed to PO when tolerated Starting day All: day −1 Other IS All: MTX10 mg/m2 day +3, +6, +11, +18 |

Time points Trough concentrations Assay Enzyme-multiplied immunoassay with whole blood Frequency Thrice weekly while inpatient, once or twice weekly while outpatient Target concentration Sibling donors: 105–155 ng/mL immunoassay, equivalent to 100–150 ng/mL HPLC All others: 155–210 ng/mL immunoassay, equivalent to 150–200 ng/mL HPLC |

Data analysis

Renal Toxicity

Acute GVHD

Chronic GVHD

NRM & overall mortality

|

Only studies evaluating the association of whole blood concentrations with clinical outcomes in alloHCT recipients over the past ten years were included. Studies from within the past ten years that only focused upon pharmacokinetics113 and studies published before September 2005 (ten years before writing) were not included.

In the abstract of Malard et al., these p-values and relative risks are given for grades II–IV acute GVHD, while in the body of the manuscript the same p-values and relative risks are given for grades III–IV acute GVHD.

Abbreviations: alloHCT: allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; BU: busulfan; CI: confidence interval; CNI: calcineurin inhibitor; CSA: cyclosporine; CY: cyclophosphamide; FLU: fludarabine; GVHD: graft-versus-host disease; h: hour(s); HLA: human leukocyte antigen; HLPC: high-performance liquid chromatography; HR: hazard ratio; IS: immunosuppression; IV: intravenous(ly); MA: myeloablative; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; MRD: matched related donor; MTX: methotrexate; MUD: matched unrelated donor; NMA: nonmyeloablative; NRM: non-relapse mortality; OR: odds ratio; PBSC: peripheral blood stem cell; PO: oral(ly); Q8h: every 8 hours; Q12h: every 12 hours; RIA: radioimmunoassay; RIC: reduced-intensity conditioning; RR: relative risk; TAC: tacrolimus; TBI: total body irradiation; UCB: umbilical cord blood; URD: unrelated donor

Figure 2. Association of mean week 2 cyclosporine (A, B) and tacrolimus (C, D) whole blood trough concentrations with grades II–IV (A, C) and grades III–IV (B, D) acute GVHD after nonmyeloablative alloHCT.

CNI concentrations were divided according to quartile. Reprinted from Ram et al.131

Abbreviations: alloHCT: allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; CSP: cyclosporine; GVHD: graft-versus-host disease; TAC: tacrolimus

CNI doses are adjusted for the occurrence of GVHD and increased serum creatinine.134 The role of TCI to ameliorate nephrotoxicity, however, is unclear. Elevated cyclosporine trough concentrations (via immunoassay or HPLC assay) are associated with a higher incidence of nephrotoxicity135,136 but contradictory results have been found.131,137 Cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity can occur even at low or normal concentrations of cyclosporine and may be a consequence of other drug- or disease-related factors known to influence the development of nephrotoxicity (e.g., genetic risk factors, concurrent use of other nephrotoxic agents, sepsis).137,138 Furthermore, pharmacogenomic risk factors for acute kidney injury have also been elusive. A retrospective trial of 121 patients found no pharmacogenomic association between CYP3A5*1>*3 and ABCB1 SNPs (1199G>A, 1236C>T, 2677G>T/A and 3435C>T) and acute kidney injury, defined as doubling of baseline serum creatinine during the first 100 days after alloHCT, or chronic kidney disease, defined as at least one glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 60 mL/min/m2 between 6 and 18 months after alloHCT.139

6.2.2. Current TCI

The precise timing of initiation, dose, and TCI methods often differ between transplant centers, so only general trends will be reviewed. The CNIs should be initiated before or immediately after donor cell infusion (i.e., days −3 to 0) when used for postgraft immunosuppression.131,140 This schedule is recommended because of the CNIs’ known mechanism of action: the phosphatase activity of calcineurin is inhibited, which subsequently leads to lower formation and secretion of several cytokines by T-lymphocytes, eventually resulting in a diminished inflammatory alloreactive response.80,82

TCI of cyclosporine and tacrolimus is performed by adjusting drug dosages with the goals of improved effectiveness and decreased toxicity. Evidence of an advantage for dosing tacrolimus or cyclosporine with TCI versus without has not been formally established in a randomized control trial. Given the narrow therapeutic indices of these agents, however, and their large interindividual pharmacokinetic variability, it is widely accepted that TCI is beneficial.91,141

There is no consensus in North America regarding the optimal target whole blood cyclosporine trough concentrations, and targets vary widely between institutions.83,142 The European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the European LeukemiaNet (EBMT-ELN) working group recommendations for a standardized practice in the prophylaxis of GVHD recommended a cyclosporine trough of 200–300 ng/mL (quantification method not specified) during the first 3–4 weeks and then 100–100 ng/mL until 3 months after alloHCT if there is no GVHD or toxicity.45 Target tacrolimus concentrations for TCI after myeloablative conditioning are generally whole blood trough concentrations of 5–15 ng/mL after LC/MS-MS analysis. Tacrolimus concentrations >20 ng/mL are associated with increased risk of toxicity, particularly nephrotoxicity.133,143 In nonmyeloablative alloHCT patients, CNI concentrations over the first 28 days are generally targeted higher than in myeloablative patients. Because no standard guidelines for TCI exist, however, most centers adopt their own approach.

6.2.3. Newer methods for TCI

Numerous studies have evaluated cyclosporine TCI based on AUC rather than the more commonly used trough concentrations in alloHCT.113,144–152 Pharmacokinetic sampling to determine the AUC has potential drawbacks, as it often entails a high level of patient inconvenience, potentially an inpatient admission, a high workload to obtain the samples, large total blood sample volume, and high assay costs.83 Therefore, the development of limited sampling schedules (LSS) is desirable. Using limited sampling schedules (LSS) can help to facilitate the TCI of cyclosporine by reducing the need for intensive, invasive sample collection, improving convenience, and lowering costs. Numerous studies have been published describing LSS to estimate total cyclosporine following intravenous83,153 or oral150,154,155 administration. The majority of these studies require measurement of cyclosporine concentrations within the first 4 h following a dose using either multiple linear regression83,150,153,155 or a maximum a posteriori (MAP) Bayesian procedures154,155 to estimate cyclosporine AUC. For both intravenous and oral cyclosporine, an LSS of three to five samples can estimate cyclosporine AUC0–12h with satisfactory accuracy (low bias and precision) relative to intensive pharmacokinetic sampling.

A MAP Bayesian personalization approach has been reported for cyclosporine trough concentration TCI in children.156 Van Rossum et al. has recently stated that popPK, using a LSS for AUC estimates and a Bayesian estimator, is the preferred TCI strategy after solid organ transplant.157 Furthermore, the construction of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models has allowed for simulations to evaluate the optimal administration schedule of cyclosporine. Gérard et al. recently showed that intermittent infusions (i.e., a 2 h infusion administered every 12 h) had higher simulated cyclosporine concentrations in the GVHD target organs but lower simulated cyclosporine concentrations in the kidney, suggesting that intermittent infusions would be superior.158

Although various LSS have been developed for tacrolimus in solid organ transplant recipients,159 none could be found for alloHCT recipients.

7. Methotrexate

Methotrexate is a structural analog of folic acid, which is a required cofactor for the synthesis of purines and thymidine. The antiproliferative effects of methotrexate are likely related to its effectiveness as postgraft immunosuppression, although the precise mechanism by which methotrexate prevents GVHD is not understood.82 Donor lymphocytes rapidly proliferate after alloHCT in response to the host antigens. Methotrexate is an inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), the enzyme responsible for converting folates to their active, reduced tetrahydrofolate forms.160 The immunosuppressive properties of methotrexate result from the depletion of intracellular tetrahydrofolate pools leading to depletion of purines and thymidylate and the subsequent inhibition of DNA synthesis in the lymphocytes.160 A combination of methotrexate and CNI (Seattle regimen) is the most widely used postgraft immunosuppressive regimen following myeloablative conditioning.35,37,40 The Seattle regimen consists of a CNI administered daily and short-course methotrexate administered on days +1, +3, +6, and +11 post-transplant. This schedule was based on dog studies, which indicated that more frequent methotrexate dosing led to severe gastrointestinal toxicity.161 Several modifications to methotrexate dosing35,37,162,163 and leucovorin rescue use (and leucovorin dosing) have been described.45 While the Seattle regimen is the most widely published,35 there is no consensus in the US,67 and only recently in Europe,45 with regard to the preferred regimen.

7.1. Pharmacokinetics

7.1.1. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion

Methotrexate is only administered intravenously to alloHCT recipients, and no studies evaluating the absorption of methotrexate in this patient population were found. In pharmacokinetic data outside of alloHCT, volume of distribution of methotrexate is 9.03 ± 4.70 L/m2 (mean ± standard deviation) and the elimination rate constant is 0.70 ± 0.22 1/h (mean ± standard deviation).164 Methotrexate binds primarily to albumin and is approximately 50% bound.165 The presence of ascites or effusions can provide a clinically important reservoir for residual methotrexate, leading to a sustained-release of low, but cytotoxic, methotrexate concentrations into the plasma. The intracellular transport of methotrexate involves an active (carrier-mediated) process at low extracellular concentrations; above low concentrations, transport is primarily by passive diffusion. Less than 10% of an intravenous methotrexate dose is eliminated by the gastrointestinal tract, and intestinal bacteria can metabolize methotrexate.165 Urinary excretion of the parent drug is the major route of methotrexate elimination. Methotrexate is filtered, reabsorbed, and undergoes storable, active tubular secretion.165 The typical time course of plasma methotrexate pharmacokinetics is biexponential with a mean initial half-life of approximately 1.5 to 3.5 h and a typical terminal half-life of 8 to 15 h.165 Altered pharmacokinetics are seen in children before adolescence and in patients with renal dysfunction.165

As part of a DDI study, Wingard et al. evaluated methotrexate pharmacokinetics in alloHCT recipients of HLA-identical sibling bone marrow grafts.166 Methotrexate was administered at a dose of 15 mg/m2 on day +1, followed by 10 mg/m2 on days +3, +6, and +11 after graft infusion. Serum methotrexate samples were drawn before and at 8, 16, 24, and 36 h after the doses on days +1 and +6. These serum samples were analyzed at a central laboratory using fluorescence polarization immunoassay (TxD; Abbott, Chicago, IL) and noncompartmental modeling.166 Eighty patients consented to this study, half of whom received cyclosporine plus methotrexate (cyclosporine/methotrexate) and half of whom received tacrolimus plus methotrexate (tacrolimus/methotrexate). Of these patients, 16 (40%) of the cyclosporine/methotrexate patients and 26 (65%) of the tacrolimus/methotrexate patients were not included in the day +1 and day +6 analyses, either because they did not receive full-dose methotrexate or because of incomplete sample collection. There were no significant differences in the methotrexate AUC or methotrexate serum concentrations between the cyclosporine and tacrolimus cohorts at any of the sampled time points. Renal function was similar between the cyclosporine and the tacrolimus cohorts. On day +1, the median (range) of the serum methotrexate AUC (μmol/h/L) was 1.60 (0.00–3.12) for the cyclosporine cohort and 1.84 (0.16–4.46) for the tacrolimus cohort. On day +6, the median (range) of the serum methotrexate AUC (reported as μmol/h/L) was 1.20 (0.04–1.32) for the cyclosporine cohort and 1.54 (0.08–3.14) for the tacrolimus cohort. The higher serum methotrexate AUC on day +1 compared to day +6 is expected, since a higher methotrexate dose is administered on day +1 (15 mg/m2) than on day +6 (10 mg/m2). Notably, only three of the 42 (5%) patients had serum methotrexate concentrations at 24 h greater than or equal to 0.05 μmol/L, which is generally the recommended threshold for administering leucovorin rescue.165 The methotrexate clearance did not differ between patients with or without advanced cancer. A pharmacodynamic analysis was not reported.

Kim et al. evaluated the pharmacokinetics/pharmacogenomics of methotrexate in alloHCT recipients.167 Twenty adult alloHCT recipients received cyclosporine with methotrexate (15 mg/m2 on day +1 followed by 10 mg/m2 on days +3, +6, and +11 post graft infusion). The participants had pharmacokinetic sampling following the administration of methotrexate on days +1, +3 and +11. The plasma methotrexate concentrations were determined by LC/MS-MS) and the 94 available concentration-time points available were subsequently used to build a popPK model. A two-compartment structural model with an exponential error model was used. The pharmacokinetic parameters of methotrexate clearance and volume of the central compartment were evaluated with the following covariates: sex, age, BSA, donor type, serum creatinine, creatinine clearance (CLCR), albumin, AST, ALT, total bilirubin, urine pH, concomitant drug treatment, and genetic polymorphisms of ABCB1, ABCC1, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase/IMP cyclohydrolase (ATIC), gamma-glutamyl hydrolase (GGH), methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), and thymidylate synthetase (TYMS). Methotrexate clearance was significantly affected by GFR in mL/min as estimated by the Cockcroft-Gault equation, concomitant penicillin administration, and the ABCB1 3435 genotype. For every 10 mL/min increase in GFR, the methotrexate clearance increased. Concurrent penicillin administration led to a decrease in methotrexate clearance. The covariates’ relationship to clearance (L/h) is given in equation 1

| (Equation 1) |

where PEN equals 1 in patients given penicillin and 0 otherwise and where HOMZ equals 1 in patients homozygous for the ABCB1 3435 TT genotype and 0 otherwise.

Individuals homozygous for a single genetic variant of the ABCB1 transporter (ABCB1 3435 TT) had a ~21% decrease in methotrexate clearance compared to wild-type or carriers of a single mutant allele (ABCB1 3535 CC or CT). The population clearance and volume of distribution for the central compartment values were 7.08 L/h and 19.4 L, respectively. The between-subject variability (BSV) of clearance and volume of distribution were estimated to be 21.6% and 73.3%, respectively. The proportional term estimate for residual unexplained variability (RUV) was 37.8%. Similar to the calcineurin inhibitors (see Section 6.1.1), HPLC is more specific for methotrexate concentrations than enzyme immunoassay or radioimmunoassay.168

7.1.2. Pharmacogenomics

As noted above (see Section 7.1.1), methotrexate clearance was impacted by the ABCB1 3435 TT genotype but not by ABCC1, ATIC, GGH, MTHFR, or TYMS genotypes in a study of 20 adult alloHCT recipients.167 MTHFR and TYMS play essential roles in intracellular folate metabolism. The association of acute GVHD169 with genetic variation in recipient and donor MTHFR (C677T and A1298C) and TYMS (enhancer-region 28-base pair repeat, TSER, and 1494del6) genotypes has been evaluated in 304 adult alloHCT recipients. The risk of acute GVHD was associated with variant MTHFR alleles in the recipient, but no association was observed for donor MTHFR genotypes or for recipient or donor TYMS genotypes.169 In a subset of this population with oral mucositis data (N=172), the recipient MTHFR genotypes were associated with the risk of oral mucositis.170

7.1.3. Drug-drug interactions

There is no apparent difference in methotrexate disposition in patients receiving CNIs, as the methotrexate AUCs (time interval of AUC not specified) after days 1+ and +6 are similar between patients receiving cyclosporine or tacrolimus.166 As discussed in the prior section, Kim et al. demonstrated an interaction between concomitant penicillin and methotrexate in twenty alloHCT recipients.167 Of these 20 patients, six received piperacillin and tazobactam and one received ampicillin and sulbactam; the remainder did not receive a penicillin derivative. This DDI is consistent with pharmacokinetic literature from other patient populations.171–173 Trimethoprim – sulfamethoxazole (TMP – SMX), often administered to alloHCT recipients as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia prophylaxis, is avoided on days of methotrexate administration because of the ability of sulfonamides to displace methotrexate from plasma binding sites and decrease renal methotrexate clearance, resulting in higher methotrexate concentrations. Because TMP-SMX can delay engraftment, it is usually not administered before engraftment occurs.77

7.1.4. Special populations

7.1.4.1. Renal or hepatic impairment, pediatric, obesity

Methotrexate is used as postgraft immunosuppression after myeloablative conditioning, which is administered to patients with no or minimal comorbidities. Therefore, it is not surprising that there are, to our knowledge, no publications regarding the pharmacokinetics of methotrexate in alloHCT recipients who have renal or liver impairment. Of note, CNI-induced nephrotoxicity may impair methotrexate clearance and necessitate a dose adjustment. There are also no reports of methotrexate pharmacokinetics in pediatric or obese alloHCT recipients. Notably, recent ASBMT guidelines did not address methotrexate dosing in obese patients.116

7.2. Current TCI

Although two pharmacokinetic studies of methotrexate were available, no published pharmacodynamic studies or TCI studies could be found for methotrexate in the setting of alloHCT. This contrasts with the wealth of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies of high-dose methotrexate used to treat childhood lymphoblastic leukemia.164 With high-dose methotrexate, methotrexate concentration-time data are used to guide leucovorin rescue with the intent of lowering toxicity. The underlying reasons for a lack of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data is not known but contributing factors may be delayed turn-around time for obtaining pharmacokinetic results and the narrow time window of methotrexate following alloHCT versus multiple cycles of methotrexate in other patient populations. Even in alloHCT, however, methotrexate toxicity – mainly in the form of hepatic, renal and mucosal toxicities – often mandates dose reductions, with only two-thirds of patients receiving the full methotrexate dose.40,174 It has been suggested that the methotrexate dose be held in alloHCT recipients with a bilirubin > 5 mg/dL or creatinine > 2 mg/dL.82 A higher prevalence of acute GVHD between days +7 and +11 has been observed with methotrexate dose reductions.82

Key points.

The immunosuppressants used for postgraft immunosuppression are characterized by large intra- and interindividual pharmacokinetic variability and by narrow therapeutic indices.

TCI, usually based on trough concentration monitoring, of cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and sirolimus has become an integral part of postgraft immunosuppression.

AlloHCT may benefit from the development of sophisticated systems pharmacology models to better understand the impact of pharmacokinetic variability upon clinical outcomes.

Improved TCI tools, particularly those using maximum a posteriori (MAP) Bayesian personalization approaches, are needed to more efficiently and accurately evaluate patients’ exposure to immunosuppressants.

Acknowledgments

The insightful comments of Rainer Storb, MD, upon an earlier draft of this review are gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA162059, CA178104, and CA182963).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Martin PJ. Overview of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Immunology. In: Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Blume KG, editors. Thomas’ Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. 4. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing; 2009. pp. 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1813–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin PJ. Overview of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Immunology. In: Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Blume KG, editors. Thomas’ Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing; 2009. pp. 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCune JS, Slattery JT. Pharmacological considerations of primary alkylators. Cancer Treat Res. 2002;112:323–45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1173-1_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCune JS, Holmberg LA. Busulfan in hematopoietic stem cell transplant setting. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:957–69. doi: 10.1517/17425250903107764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jonge ME, Huitema AD, Rodenhuis S, Beijnen JH. Clinical pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:1135–64. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCune JS, Woodahl EL, Furlong T, et al. A pilot pharmacologic biomarker study of busulfan and fludarabine in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:263–72. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doroshow JH, Synvold TW. Pharmacologic Basis for High-dose Chemotherapy. In: Appelbaum F, Forman S, Negrin R, Blume K, editors. Thomas’ Hematopoietic Cell Transplant. 4. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing; 2009. pp. 289–315. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cinader B. Aging and the Immune System. In: Delves PD, Roitt IM, editors. Encyclopedia of Immunology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al. Age, thymopoiesis, and CD4+ T-lymphocyte regeneration after intensive chemotherapy [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1995;332:143–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savage WJ, Bleesing JJ, Douek D, et al. Lymphocyte reconstitution following non-myeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation follows two patterns depending on age and donor/recipient chimerism. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:463–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eder JP, Elias A, Shea TC, et al. A phase I–II study of cyclophosphamide, thiotepa, and carboplatin with autologous bone marrow transplantation in solid tumor patients. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1239–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deeg HJ, Maris MB, Scott BL, Warren EH. Optimization of allogeneic transplant conditioning: not the time for dogma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1701–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storb R, Gyurkocza B, Storer BE, et al. Graft-versus-host disease and graft-versus-tumor effects after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1530–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron F, Baker JE, Storb R, et al. Kinetics of engraftment in patients with hematologic malignancies given allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood. 2004;104:2254–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron F, Little MT, Storb R. Kinetics of engraftment following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with reduced-intensity or nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood Rev. 2005;19:153–64. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McSweeney PA, Niederwieser D, Shizuru JA, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with hematologic malignancies: replacing high-dose cytotoxic therapy with graft-versus-tumor effects. Blood. 2001;97:3390–400. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kekre N, Antin JH. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation donor sources in the 21st century: choosing the ideal donor when a perfect match does not exist. Blood. 2014;124:334–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-514760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballen KK, Gluckman E, Broxmeyer HE. Umbilical cord blood transplantation: the first 25 years and beyond. Blood. 2013;122:491–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-453175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballen KK, Koreth J, Chen YB, Dey BR, Spitzer TR. Selection of optimal alternative graft source: mismatched unrelated donor, umbilical cord blood, or haploidentical transplant. Blood. 2012;119:1972–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-354563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackall C, Fry T, Gress R, Peggs K, Storek J, Toubert A. Background to hematopoietic cell transplantation, including post transplant immune recovery. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:457–62. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayraktar UD, Champlin RE, Ciurea SO. Progress in haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:372–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Donnell PV, Luznik L, Jones RJ, et al. Nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation from partially HLA-mismatched related donors using posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8:377–86. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12171484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appelbaum FR. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia when a matched related donor is not available. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008:412–7. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1487–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNeil C. Preventing graft-versus-host disease: transplanters glimpse hope beyond immunosuppressants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:922–3. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho VT, Soiffer RJ. The history and future of T-cell depletion as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:3192–204. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin PJ, Hansen JA, Buckner CD, et al. Effects of in vitro depletion of T cells in HLA-identical allogeneic marrow grafts. Blood. 1985;66:664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horowitz MM. High-resolution typing for unrelated donor transplantation: how far do we go? Best practice & research. 2009;22:537–41. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersdorf EW, Kollman C, Hurley CK, et al. Effect of HLA class II gene disparity on clinical outcome in unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia: the US National Marrow Donor Program Experience. Blood. 2001;98:2922–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens CE, Carrier C, Carpenter C, Sung D, Scaradavou A. HLA mismatch direction in cord blood transplantation: impact on outcome and implications for cord blood unit selection. Blood. 2011;118:3969–78. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersdorf EW, Gooley TA, Malkki M, et al. HLA-C expression levels define permissible mismatches in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2014 doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-599969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiden PL, Doney K, Storb R, Thomas ED. Anti-human thymocyte globulin (ATG) for prophylaxis and treatment of graft-versus-host disease in recipients of allogeneic marrow grafts. Transplant Proc. 1978;10:213–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deeg HJ, Storb R, Thomas ED, et al. Cyclosporine as prophylaxis for graft-versus-host disease: a randomized study in patients undergoing marrow transplantation for acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1985;65:1325–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Whitehead J, et al. Methotrexate and cyclosporine compared with cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of acute graft versus host disease after marrow transplantation for leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:729–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603203141201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsay NK, Kersey JH, Robison LL, et al. A randomized study of the prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:392–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198202183060703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Pepe M, et al. Methotrexate and cyclosporine versus cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease in patients given HLA-identical marrow grafts for leukemia: long-term follow-up of a controlled trial. Blood. 1989;73:1729–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Farewell V, et al. Marrow transplantation for severe aplastic anemia: methotrexate alone compared with a combination of methotrexate and cyclosporine for prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1986;68:119–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nash RA, Antin JH, Karanes C, et al. Phase 3 study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus with methotrexate and cyclosporine for prophylaxis of acute graft-versus-host disease after marrow transplantation from unrelated donors. Blood. 2000;96:2062–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]