Abstract

Studies show that policing, when violent, and community fragmentation have a negative impact on health outcomes. This current study investigates the connection of policing and community fragmentation and public health. Using an embedded case study analysis, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 21 African-American female and male residents, ages 21–64 years of various neighborhoods of high arrest rates and health and socioeconomic depravation in Baltimore City, MD. Baltimore residents’ perceptions of policing, stress, community fragmentation, and solutions are presented. Analysis of the perceptions of these factors suggests that violent policing increases community fragmentation and is a public health threat. Approaches to address this public health threat are discussed.

Keywords: Policing, Police violence, Community fragmentation, Stress, Racism, Public health, Racial profiling, Baltimore

Introduction

Social cohesion—the ability of a community to stand together—contributes to population health by giving members of the community a sense of control and the power to affect what occurs in the community.1,2 Community fragmentation, or lack of social cohesion, can result from many processes and is associated with poor health.3–9 One process that may be linked to community fragmentation and ill health is violent policing.

Baltimore, MD, experienced its share of heightened attention to the problem of police violence after Freddie Gray, a young black man, was killed in police custody April 19, 2015. Across the city, residents organized and protested against police violence and economic deprivation. Six officers were indicted for police violence and homicide.10 While the case had not been tried as of this writing (2015), civil claim payouts to the family of this victim of a spinal cord injury during a van ride occurred quickly in the highest amount in Baltimore’s history, $6.4 million.11

The public outcry reflects the fact that there is a long history of police violence and expanded use of police power against the most marginalized in Baltimore.12,13 “Undue Force,” an investigative series by the Baltimore Sun newspaper, revealed that between 2011 and 2014, 317 lawsuits were filed against Baltimore City police officers, alleging civil rights and constitutional violations including false arrest, battery, and false imprisonment.14 These lawsuits resulted in 102 court judgments and settlements for police brutality, with payouts of about $5.7 million. The series concluded:

Those cases detail a frightful human toll. Officers have battered dozens of residents who suffered broken bones — jaws, noses, arms, legs, ankles — head trauma, organ failure, and even death, coming during questionable arrests. Some residents were beaten while handcuffed; others were thrown to the pavement.... City policies help to minimize transparency of the scope and impact of beatings from the public.

Violent policing at very high rates harms not only individuals but also communities. Under the “Zero Tolerance” policy enacted in Baltimore in 2005, police officers targeted low-income and African-American communities with high crime rates.15,16 In 2005, more than 100,000 arrests occurred in a city of 640,000 people; 17–35 % of arrests were interpreted as “no probable cause,” and arrests ending with “release without charges” increased between 2000 and 2005.15,16 At that rate of arrest, the policing became a form of structural violence and had a major effect on day-to-day community life.17–19 Because violent policing is linked to a number of harms to individuals and to communities, it might contribute to community fragmentation and poor health, a connection that will be investigated in this paper.

Method

This study employed an embedded case study method to analyze the role of policing in community fragmentation and public health.20 The study was designed to see if community perception of police action linked it to community fragmentation and poor health.

Timeline of the Study

The study was carried out over a period of 8 weeks, April 1 to May 31, 2015. The arrest and injury of a young African-American man—Freddie Gray—by Baltimore city police occurred on April 12 in Sandtown-Winchester (one of the neighborhoods addressed in this study). On April 19, Freddie Gray died of injuries suffered during his arrest, and his death was ruled a homicide. Peaceful protests began on April 18 and continued with mass protesting and uprising after his funeral on April 22. During the uprising on April 22, looting occurred, and businesses and cars were set on fire across several Baltimore neighborhoods, resulting in the deployment of state troopers and the National Guard. A curfew and state of emergency were declared during the week after the uprising. Peaceful protests continued during and after this week. On May 1, five of the six police officers involved in the arrest were charged with murder by the state prosecutor’s office with the issuance of the medical examiner’s report that he “Suffered a critical neck injury as a result of being handcuffed, shackled by his feet and unrestrained inside the BPD [Baltimore Police Department] wagon.”21 The sixth officer was charged with second-degree assault, misconduct, and false imprisonment. During the weeks after charges were brought against the police officers, police response to calls for help decreased and shootings increased.

Community Health Data

The Baltimore Neighborhood Indicator Alliance, The Jacob France Institute (BNIA)22 in Baltimore, MD, provided information on health and socioeconomic status, based on data from the US Bureau of Census 2010 decennial census and the American Community Survey for the period 2009–2013. Data on gun violence and probation/parole was obtained from the Baltimore City Police Department. Data on infant mortality and life expectancy were obtained from the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Vital Statistics Administration. These data were used to create Table 1. Data on vacancies were obtained from the Baltimore Housing department, mapped by BNIA. Neighborhoods are categorized as community statistical areas (CSA) using BNIA’s geographic boundaries and may include multiple zip codes and census tract areas.

TABLE 1.

Socioeconomic and health demographics of neighborhoods

| Indicators | Clifton/Berea | Madison East End | Oldtown/Middle East | Pimlico | Sandtown-Winchester | Southern Park Heights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population (2010) | 9874 | 7781 | 10,021 | 11,816 | 14,896 | 13,284 |

| Percent of Black/African-American population (2010), by quintilea | 5th | 5th | 5th | 5th | 5th | 5th |

| Percent of household earning less than $25,000 (2009–2013), by quintileb | 4th | 4th | 5th | 5th | 5th | 5th |

| Percent of the population aged 16–64 unemployed and looking for work (2009–2013), by quintilec | 3rd | 5th | 5th | 4th | 5th | 5th |

| Percent population over 25 with less than a high school diploma (2009–2013), by quintiled | 4th | 5th | 5th | 5th | 4th | 4th |

| Gun-related homicide rate per 1000 (2013), by sextilee | 5th | 5th | 4th | 4th | 5th | 4th |

| Percent adult population on parole or probation (2013), by quintilef | 5th | 5th | 4th | 4th | 5th | 4th |

| Mortality aged less than 1 year rate by 10,000 (2013), by quintileg | 5th | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 5th | 4th |

| Life expectancy average years (2013), by quintileh | 5th | 5th | 3rd | 5th | 4th | 4th |

aQuintiles are 2.7–20.4 %, 20.5–38.0 %, 38.1–69.0 %, 69.1–88.2 %, and 88.4–96.7 %

bQuintiles are 9.0–22.3 %, 22.4–31.5 %, 31.6–40.7 %, 40.8–51.2 %, and 51.3–66.3 %

cQuintiles are 2.8–5.4 %, 5.5–8.3 %, 8.4–10.5 %, 10.6–13.2 %, and 13.3–17.0 %

dQuintiles are 1.2–7.4 %, 7.5–14.6 %, 14.7–20.9 %, 21.0–28.3 %, and 28.4–39.7 %

eQuintiles are (per thousand population) 0, 0.10–0.14, 0.15–0.30, 0.31–0.60, and 0.61–1.16

fQuintiles are 0.6–2.2 %, 2.3–4.6 %, 4.7–7.0 %, 7.1–9.1 %, and 9.2–14.5 %

gQuintiles are (per ten thousand population) 9.0–22.3, 22.4–31.5, 31.6–40.7, 40.8–51.2, and 51.3–66.3

hQuintiles are (average years) 66.0–68.8, 68.9–71.3, 71.4–74.5, 74.6–78.8, and 78.9–85.3

Neighborhoods were selected because they were known to be sites of high police activity.23 Participants for this case study lived in the following areas: Clifton/Berea, Madison/East End, Oldtown/Middle East, Sandtown-Winchester, Southern Park Heights, and Pimlico. Table 1 shows the socioeconomic and health indicators of neighborhoods where interviews were conducted. These neighborhoods are majority African-American. All six neighborhoods ranked in the worst quintiles—4th and 5th—on four of five socioeconomic indicators of depravation (households earning less than $25,000; population over 25 with less than a high school diploma; gun-related homicide rate per 1000; percent of adult population on parole or probation). Five of the six neighborhoods studied ranked in the worst quintiles for infant mortality. Five of six neighborhoods ranked in the worst quintiles for life expectancy.

Community Interviews

Semi-structured/key informant interviews were conducted with community members in different neighborhoods in Baltimore, MD, to obtain perceptions of policing, community fragmentation, and stress in their neighborhoods. Eligibility criteria included ability to provide informed consent, age 18 and older, and working or living in the targeted neighborhoods.

Participants were engaged while sitting on their stoops or standing on street corners or were referred by other interviewees identified by these methods. The demographics of the participants in key informant interviews are presented in Table 2. One-hundred percent of those interviewed identified as Black/African-American. The author approached 24 people and 21 agreed to being interviewed (an 87.5 % response rate).

TABLE 2.

Demographics of key informants of semi-structured interviews

| Participants | n |

| 21 | |

| Age range | Years |

| 22–68 | |

| Age groups (years) | n |

| 21–30 | 6 |

| 31–40 | 7 |

| 41–50 | 3 |

| 51–60 | 4 |

| 61–70 | 1 |

| Gender | n |

| Female | 7 |

| Male | 14 |

| Race/ethnicity | % |

| African-American | 100 |

| Community statistical area (CSA) | n |

| East Baltimore | |

| Madison East End | 3 |

| Clifton/Berea | 4 |

| Oldtown/Middle East | 4 |

| West Baltimore | |

| Sandtown-Winchester/Harlem Park | 4 |

| Pimlico/Arlington/Hilltop | 2 |

| Southern Park Heights | 4 |

| Living in community (years grouped) | n |

| 1–10 | 7 |

| 11–20 | 5 |

| 21–30 | 5 |

| 31–40 | 2 |

| 41–50 | 1 |

| 51–60 | 0 |

| 61–70 | 1 |

A semi-structured interview with prompt questions was used by the author, and pen and paper was used to document responses. Prompt questions explored perceptions of policing, encounters with police, stress, community fragmentation, fear of police, and community improvement—what do you think about policing in your neighborhood? Have you or anyone you know had any encounters with the police? Are you afraid/do you worry about the police/do you think folks in your neighborhood are afraid/worry about the police? What about the police, do you think they are afraid of folks in your community? Do you think policing affects your community being fragmented? What do you think are solutions/challenges to changing/improving your neighborhood? Interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min. Responses were coded for violence, stress, and fragmentation. A community advisory board from the East Baltimore community approved the design and implementation of this study.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

The great strength of the study is that it interviewed people in poor neighborhoods at a time when the issue of police violence had reached a high level of salience. As a street intercept study, the author talked to people who were outside and those most likely to have encounters with the police. This helped to understand the ways in which the community encounters the police, but may have inflated the perception of the frequency and violence of police encounters.

Results

Desertification of the Neighborhoods

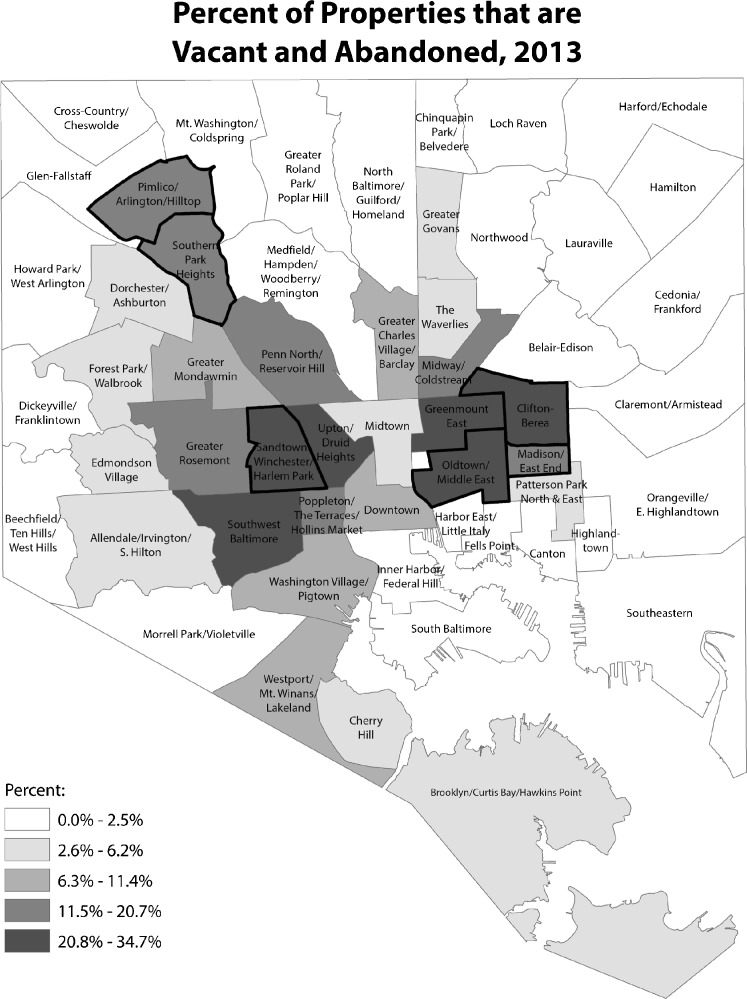

The map in Fig. 1 shows the rates of vacant and abandoned properties in Baltimore, MD, with the darkest colors representing the highest rates of vacancy. The solidity with which the map is colored belies the actual fragmentation of the landscape that one encounters in the high-vacancy neighborhoods that were the focus of this study. The desertification of the urban landscape has been at the heart of the fragmentation of poor, African-American neighborhoods in Baltimore.

FIG. 1.

Percent of properties that are vacant and abandoned, 2013, Baltimore.

As one walks through these neighborhoods, consecutive blocks of fully boarded or half-boarded houses are present. In another two blocks, there may be no houses boarded. On another, there may be one house occupied, with the remaining houses on that block boarded (Fig. 2). In the backyard of many of the abandoned and boarded houses, trash piles are present. There are sofas, refrigerators, and mattresses present in some empty lots and behind boarded houses. Some of the boards on the windows and doors of some abandoned houses have been removed, and one can see into what was once a home. Often it is mostly dark inside, some with trash on the floors. Some have no roofs while several had tree branches covering the windows. One house had a tree growing up from the earth inside. The feeling is a sense of desertification, abandonment, and fracturing. On some streets, the feeling of hope is gone, a sense of injury and pain remains. On some blocks, though not boarded, no one sits on the stoops. On the blocks where people are on the corners or sitting on the stoop, there are others sitting on their stoops (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Images of boarded neighborhood in Sandtown-Winchester and Clifton/Berea.

FIG. 3.

Images of piled trash in Sandtown-Winchester and Clifton/Berea.

Living in Fragmentation

Despite high levels of desertification and depravation, residents of the area remain friendly and interested in talking about their situation. The issue was on people’s minds and they had a lot to say. They were clear that the community was fragmented. Many had isolated themselves as a way to manage the difficulties. One noted

So will the community come together? No. I wish this place was better…maybe people would start getting along with each other. A lot of fighting…way too much beef, attitude, anger, hatred, jealousy. Majority of time for something dumb, don’t need to be dying and fighting. (22-year-old female, 4 years in CSA)

The rate of murder in the neighborhood—some of it a result of the “beef, attitude, anger, hatred, jealousy”—was very high. There had been 38 murders during one month of this fieldwork. One study participant noted “Police don’t have to go out and kill us, we killing ourselves…”

An older woman, who had grown up in a different time, commented on the shift in ethos that had taken place.

When I was brought up, if I didn’t go to church I couldn’t go outside. 8 PM be on the step, 9 PM inside the house. Playing was fun, that’s it. But now parents they got so much on their mind. The kids running around and throwing stones at cars for fun, little kids… not nice. I just tell them God don’t like ugly. (65-year-old female, 13 years in CSA)

She continued, commenting on the community-police relationship, in the same vein of disapproval for loss of control of young people’s behavior, a major sign of community fragmentation:

[Police] trying to do their job. Not afraid of us. I respect them. Younger generation want to be smart with them. They play games with the police. Some of the police play too but some of them don’t. Some of the kids play in the wrong way with them and the police retaliate. Parents don’t bring the kids up right. (65-year-old female, 13 years in CSA)

How Did Police Act?

All the interviewees related some personal or observed occurrence of police violence in their neighborhoods, including 18 who reported they had personally been stopped by the police. While at least one person acknowledged that there were some good and some bad police, the overall impression was that the police used intimidation and racial assault to carry out their work. One informant explained

It’s a hate crime thing, a racial type thing. When they harass black men and women for no apparent reason, to see it is different…has a lot to do with the color of your skin. Back in the day, like slavery…“you niggas” all cops say it (50-year-old female, 35 years in CSA)

Informants’ observations consistently confirmed the sense that the police were policing the people of the neighborhood, rather than protecting the neighborhood from crime. An interviewee remembered

When I worked on Monument a police was stopping a woman walking down the sidewalk with her dog. Back then, you couldn’t walk your dog on the side walk. He was yelling at her, calling her black “bitch.” Sheila Dixon was walking by, was on the City Council at that time…said the officer did not have to talk to the woman like that. The officer told Sheila Dixon that she should shut up and keep walking. Next thing you know, she called Sheila Dixon a black “bitch” and started calling her names, grabbed her, cuffed her, and had her sitting on the side walk. [Note: Sheila Dixon was later Mayor of Baltimore, 2007–2009] (55-year-old male, 50 years in CSA)

Another interviewee underscored this sense of “us” and “them” in describing multiple experiences of police harassment.

I get stopped and harassed all the time…always think I was a guy…walking and they tell me to “stop and stand against the wall, put your hands on top of your head, don’t move, where’s your ID at, do you live at the address on the ID…tired of getting harassed in Baltimore. We were just in PA and no one harassed me. Started getting harassed at 16…I think they’re violent and they think we’re violent…that’s why they’re so violent first. We afraid of them too, to a certain extent…every time you see a po-po [police] you think you’re getting harassed (30-year-old female, 30 years in CSA)

As noted by previous speakers, the harassment started at a very young age. One interviewee explained

Police don’t look at kids as kids, look at them as grown, adults. Then they start treating them in a certain way. I see the police cussing them, slamming them on the ground, verbally abusing them. These kids they 12 and 13 but 6 feet tall. But the police treat them like they grown. I’m disgusted with how they treat them. They went to college but not doing right by the job. They have kids too…I respect you if you respect me. I disapprove of when they go and question a 9 or 8 years old kid, not right. Not their job to question babies…but they’ll tell them what they see so that’s why they harass them. Of course when they question your kid then they find out a bunch of stuff (65-year-old female, 13 years in CSA)

The harassment started young, but continued throughout life, as reported by a number of middle-aged men. One interviewee noted

First time I was harassed was 16. Since then I get harassed/stopped at least once every year. This is all a system problem…What happen with Freddie Gray is not a one-time occurrence. Last time I got harassed, I was driving and pulled over, profiled. Some guys walked past and distracted the police. They just left me there, told me to go. Didn’t pull me over for anything. They have to meet that quota. (38-year-old male, 10 years in CSA)

Might Police Action Have Added to Community Fragmentation?

It is widely acknowledged among students of urban process that the free-moving street life of a community is essential to its functioning. Interviewees described the highly disruptive police actions in this presumably public space. This story of harassment of shoppers captures this fundamental harm to neighborhood life:

We’re just standing in front of the Chinese carry out…just waiting for our food…and the police come and tell us to move along. Move along?…we’re waiting for our food…thought the side walk was public property…we can’t stand on the corner in our own community? They want to pat us down…ask us if we have guns…we call it “SWB”…you know what that means? Means “standing while black”…if you black you can’t stand on the corner…did you know that? Not the first time I been harassed or seen other people. Too many times to count. Affects me, all of us…it makes us angry…we have so much anger inside…pushed down…because they keep treating us all like criminals…see two of us together and we’re criminals…how can we be together in our community? What do we do with this anger? We can’t even talk on the corner, SWB (45-year-old male, 8 years in CSA)

At the extreme, officers acted to drive everyone off the street, as in this story:

Another time, I was on Jefferson street in the afternoon. This police got out off the car and told everyone standing on the sidewalk, sitting on their stoops, to get into their houses because this was his street and nobody was allowed outside. I don’t know what to think about that…felt like this could be a German gestapo, know what I mean? (60-year-old male, 50 years in CSA)

People did not feel free to move about in the neighborhoods because of the constant threat of being stopped by the police. One man noted he made it a point to be in the house by 10 PM. Another concluded “Police harassment breaks the community down. People stick to themselves. Middle age kind of stick to themselves… Everybody in their own area.” (50-year-old male, 35 years in CSA)

In addition to the loss of freedom of movement, community fragmentation was augmented by the social, psychological, and economic costs of arrest. One man spent two months in jail for a false arrest. A woman reported that she had to pay a large fine to get her daughter out of jail, and this had thrown off her ability to pay her gas and electric bill. The daughter’s criminal record made it hard for her to get employment. In general, the lasting stigma of arrest created an important obstacle to employment. One interviewee noted

Feel like [the community] don’t want no criminals involved, make me feel like I can’t get no job either. Cause once you arrested, you can’t get a job…I had an interview at EBDI [East Baltimore Development Inc.] security and they said they would hire me, say it’s okay that I had a record. Then they didn’t call and when I call them they say can’t hire me because need me to work more hours…don’t tell me anything about my record. (30-year-old female, 30 years in CSA)

Other interviewees spoke of the talent many previously incarcerated people had:

How come you won’t hire an ex-convict? Why can’t give them a break? Ex-convicts have a lot of skills, some of them really smart. Can’t find a job. (32-year-old male, 5 years in CSA)

On the one hand, the community was stressed by the actions of the police. On the other hand, there was real crime in the neighborhood, for which the police were needed. This became particularly acute in the aftermath of the Freddie Gray murder, when the police started a slowdown action and refused to enter the neighborhoods at all:

Finally someone at the top did the right thing [referring to the indictment of 6 policer offers for the murder of Freddie Gray less than one month ago in Baltimore]. See what happened? The police stop working. We need them. Just need them to stop harassing black people… Now you see them retaliating. Not coming out to the community when we call. They retaliating against us. That’s not right. (65-year-old female, 13 years in CSA)

What Did Interviewees Think Should Be Done?

Interviewees were clear that the fundamental resources for community life were needed if things were to change. These included housing, recreation, education, and employment. One participant pointed out

Need housing, look at all these houses, vacant for so long. Got so many homeless people, no place to live, sleeping in vacant house; get together with another homeless person and cause some trouble. They giving the police so much money but they not doing their job. Need money to clean up the streets. I love Baltimore, don’t want to go anywhere else. Start with this house, they need to fix it. I rent, he’s a slumlord. but I have to try and fix it myself. (65-year-old female, 13 years in CSA)

That alone, it was widely agreed, would not stop the police violence. Numerous proposals were made to improve the behavior of the police, including hiring local people who would be sympathetic to the community, holding the police accountable when they were wrong, putting civilian intake personnel in the jail system to protect those arrested, and improving evaluation of police recruits. Most interviewees mentioned that the “war on drugs” was really a “war on black people” carried out by corrupt police officers and should be stopped. They felt the focus should be on all crime in the community, not only the problem of drugs:

Biggest gang around are the police. Some of them good, most of them crooked. If they see you and they don’t like you, pat you down for drugs, plant things on you sometimes. Cops are corrupt…we don’t respect them because they don’t do their jobs. (34-year-old male, 2 years in CSA)

For the part of the problem that had to do with collapse in the community’s ethos of behavior, schools, prayer, and recreation were thought to be the major interventions that might help. One dedicated community leader said

Right now we got money coming into Baltimore after the Freddie Gray stuff. But that money going to the same people, the same pipeline. People trying to fix the unfixable. We need crime, part of everything, you need it. This is life. Have to face this, and manage and balance the crime with the good things. That’s reality. That said, we have to balance the table. Get more rec [recreational] centers, youth organizations, more good to fight the bad. If you think you can eliminate the bad you dreaming. Have to balance it. I have this mentoring center here, grandmother lived in that house across the street [the block is boarded and abandoned]. Never left. (38-year-old male, 10 years in CSA)

Discussion

Results of this study suggest that Baltimore’s poor, African-American neighborhoods, which have been disinvested and fragmented, are prime targets for the “war on drugs” policies. This hyper-targeting of neighborhoods increases the risk of police violence. Residents felt that these conditions of disinvestment and deterioration were havens for police violence. Police violence was enacted through racial profiling, corruption, and insufficient training. Residents felt that police violence increased fragmentation and decreased cohesion and healthy social networks. Stress and worry, resulting from fear of police harassment and a sense of disempowerment, were reported as contributors to community fragmentation and poor health. Residents felt that the criminal justice system lacked transparency and accurate data collection. They felt it needed accountability to acknowledge the history of police violence and identify ways to remedy and prevent its continuation. Residents also recognized that the systems that maintain disinvestment in education, employment, housing, recreation, criminal justice, and segregation needed to be changed.

This study confirms previous qualitative studies reporting police violence in communities and places of high drug use and drug markets, poverty, and predominantly African-American.24–27 It offers empiric analysis of community fragmentation and stress as a result of police violence. This study supports the hypothesis that policing results in community fragmentation. The results suggest that police violence increases the risk of negative health outcomes from chronic exposure to stressful environments and therefore is a public health threat, supporting previous studies on violence and public health threat.9,28,29

One short-term approach in addressing violence by police is mandatory data collection of injuries reported by those affected. Another is to increase funding for evaluation and training for culturally competent policing. Another short-term approach to addressing policing enacted through the “war on drugs” in distressed communities is to require more research to determine evidence-based practices which will lead to improved public health for everyone.30,31

A long-term approach requires a cross-sectoral action. This will require affected community, planners, policy makers, and advocates of law enforcement, public health, economic and community development, schools, recreation, and housing to be at the table to identify how each impact and is impacted by crime, policing, and police violence. The sequela of segregation of communities and its role in affecting the existing fragmentation and vulnerability to drug markets and hyper-policing requires further investigation. A root cause analysis and policy and funding to systematically desegregate and equalize such communities should be a long-term goal.32

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the residents who candidly offered their insight in regard to policing and Cheryl Knott at BNIA for her help with secondary data.

References

- 1.Chavis DM, Pretty GMH. Sense of community: advances in measurement and application. J Community Psychol. 1999;27:635–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199911)27:6<635::AID-JCOP1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolcock M, Narayan D. Social capital: implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Res Obs. 2002;15:225–48. doi: 10.1093/wbro/15.2.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried M. Grieving for a lost home: psychological cost of relocation. In: Wilson JQ, ed. Urban renewal: the record and the controversy. Boston, MA: MIT Press; 1966.

- 4.Fullilove M, Wallace R. Serial forced displacement in American cities: 1916–2010. J Urban Health. 2011;88:381–9. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9585-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naraya D, Patel R, Schafft K, Rademacher A, Koch-Schulte S. Social fragmentation. In “Voices of the poor: can anyone hear us?” World Health Organization. 2000. New York: Oxford University Press. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2000/03/437850/vo. http://search.worldbank.org/all?qterm=social+fragmentation&title=&filetype= Accessed October 20 2015.

- 6.Gomez MB, Muntaner C. Urban redevelopment and neighborhood health in East Baltimore, Maryland: the role of communitarian and institutional social capital. Crit Public Health. 2005;15:83–102. doi: 10.1080/09581590500183817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. The impact of a police drug crackdown on drug injectors’ ability to practice harm reduction: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:673–84. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diez-Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;9:1783–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng Y, XianChen LB, Chaohua L, Freya L, et al. The association between social support and mental health among vulnerable adolescents in five cities: findings from the study of the well-being of adolescents in vulnerable environments. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:S31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blinder A, Perez-Pena R. Six Baltimore police officers charged in Freddie Gray death. New York Times. May 5 2015 http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/02/us/freddie-gray-autopsy-report-given-to-baltimore-prosecutors.html?_r=0. Accessed May10 2015.

- 11.Wenger Y, Puente M. Baltimore to pay Freddie Gray’s family $6.4 million to settle civil claims. Baltimore Sun. September 8 2015 http://touch.baltimoresun.com/#section/-1/article/p2p-84378265/ Accessed October 2015.

- 12.Stolberg CG. Baltimore’s “broken relationship” with police. New York Times. April 24 2015 http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/25/us/baltimores-broken-relationship-with-police.html?_r=1 Accessed October 20 2015.

- 13.Tabor N. The mayor who cracked down on Baltimore. Jacobin Magazine. May 14 2015. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/05/omalley-baltimore-clinton-democratic-primary-president/ Accessed October 20 2015.

- 14.Puente M. Undue force. Baltimore Sun. September 28 2014 http://data.baltimoresun.com/news/police-settlements/ Accessed May 30 2015.

- 15.Janis S. Why did they arrest me? Washington Examiner July 17 2006 http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/why-did-they-arrest-me/article/69845. Accessed May 1 2015.

- 16.Sarah LB. Justice undone: examining arrests ending in release without charges in Baltimore City. A thesis submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Policy. Baltimore, Maryland; 2007. http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/institute-for-health-and-social-policy/_docs/the-abell-award/winning-papers/2007-brannen.pdf Accessed December 23 2015.

- 17.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. (Eds.). World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2001. pp. 5–6 http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/introduction.pdf Accessed May 12 2015.

- 18.Galtung J. Violence, peace, and peace research. J Peace Res. 1969;6:167–91. doi: 10.1177/002234336900600301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander M. The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press; 2012.

- 20.Scholz RW, Tietje O. Embedded case study methods: integrating quantitative and qualitative knowledge. London, UK: Sage Publications Inc.; 2002.

- 21.Blinder A, Perez-Pena R. Six Baltimore police officers charged in Freddie Gray death. NY Times. May 1 2015.

- 22.Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance The Jacob France Institute Map Gallery http://bniajfi.org/mapgallery/ Accessed March 2 2015.

- 23.Baltimore City Police Department. Arrest records. 2015 https://data.baltimorecity.gov/Public-Safety/BPD-Arrests/3i3v-ibrt Accessed January 2015.

- 24.Linton SL, Jennings JM, Latkin CA, Gomez MB, Mehta SH. Application of space-time scan statistics to describe geographic and temporal clustering of visible drug activity. J Urban Health. 2014;91:940–56. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9890-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashim K, Small W, Csete J, Hattirat S, Kerr T. Experiences with policing among people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand: a qualitative study. PLoS Med. 2013;10(12):e1001570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markwick N, McNeil R, Small W, Kerr T. Exploring the public health impacts of private security guards on people who use drugs: a qualitative study. J Urban Health. 2015;92:1117–30. doi:10.1007/s11524-015-9992-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Rothstein R. From Ferguson to Baltimore: the fruits of government sanctioned segregation. April 29, 2015. Economic Policy Institute. http://www.epi.org/blog/from-ferguson-to-baltimore-the-fruits-of-government-sponsored-segregation/ Accessed October 24, 2015.

- 28.Merkin SS, Arun K, Roux AV, Seeman T. Life course socioeconomic status and longitudinal accumulation of allostatic load in adulthood: multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e48–55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merkin SS, Basurto-Davila R, Karlamangla A, et al. Neighborhoods and cumulative biological risk profiles by race/ethnicity in a national sample of U.S. adults: NHANES III. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;19:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleveland MM. Economics of illegal drug markets: what happens if we downsize the drug war? In: Fish JM, editor. Drugs and society: U.S. public policy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2006. pp. 173–96. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The negative impact of the war on drugs on public health: the hidden hepatitis C epidemic. Global Commission on Drug Policy. May 2013. http://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/hepatitis/gcdp_hepatitis_english.pdf Accessed October 20 2015.

- 32.Coates TN. The case for reparations. The Atlantic. June 2014 http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/ Accessed October 20 105.