Abstract

Police brutality, a longstanding civil rights issue, has returned to the forefront of American public debate. A growing body of public health research shows that excessive use of force by police and racial profiling have adverse effects on health for African Americans and other marginalized groups. Yet, interventions to monitor unlawful policing have been met with fierce opposition at the federal, state, and local levels. On April 30, 2015, the mayor of Newark, New Jersey signed an executive order establishing a Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) to monitor the Newark Police Department (NPD). Using a mixed-methods approach, this study examined how advocates and government actors accomplished this recent policy change in the face of police opposition and after a 50-year history of unsuccessful attempts in Newark. Drawing on official public documents, news media, and interviews conducted in April and May 2015, I propose that: (1) a Department of Justice investigation of the NPD, (2) the activist background of the Mayor and his relationships with community organizations, and (3) the momentum provided by the national Black Lives Matter movement were pivotal in overcoming political obstacles to reform. Examining the history of CCRB adoption in Newark suggests when and where advocates may intervene to promote policing reforms in other US cities.

Keywords: Police brutality, Newark, Civilian review, Racial profiling, Police-community relations, New Jersey, Civil rights

Introduction

The killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in August 2014 has thrust the issue of police brutality and discriminatory policing practices back to the center of public debate. Increasingly, cases of police overuse of force spark massive popular unrest and serve as the impetus for days- or months-long demonstrations. This is not a new phenomenon: today’s unrest is hauntingly reminiscent of what occurred in the 1960s, when police violence sparked a cascade of urban rebellions,1 in Watts, California; Detroit, Michigan; Newark, New Jersey, and cities across the country. In Newark, the site of a bloody 1967 uprising in response to police abuse, frayed relations between law enforcement and African Americans have persisted amidst decades of calls for policing reforms.1–3 A 2014 Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation found the Newark Police Department (NPD) guilty of repeatedly violating citizens’ rights through discriminatory policing practices and excessive use of force, confirming what civil rights activists have asserted for generations.3,4

Police brutality is not solely a civil rights issue. The effects of police violence on African Americans are also among several drivers of health disparities in the USA. Data on police deadly use of force is not systematically collected by the DOJ, but evidence compiled by journalistic sources estimate that there are about 1000 police killings in the USA annually.5–7 A growing body of public health literature shows that police-perpetrated violence produces individual and collective trauma through neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse.8–13 African Americans are more likely to be stopped and frisked by police, in part because their neighborhoods are more likely to be sites of heavy policing.11,14 Neighborhood patterns of police surveillance may serve as a barrier to accessing care for other marginalized populations such as substance users and sex workers, as these criminalized populations may avoid seeking clean needles or care for fear of punishment.9,13,15–21 The greater likelihood of experiencing police violence exists alongside widely reported poor health outcomes among African Americans, such as higher rates of cardiovascular illness and earlier onset of disease than their white counterparts.22

In response to popular pressure to address police misconduct, federal, state, and city governments are proposing various policy reforms—such as body and vehicle cameras, independent prosecutors, and civilian review boards. The civilian review board is a highly controversial measure, and its political history in Newark is the focus of this study. These boards are oversight mechanisms whereby victims of police misconduct may raise complaints and seek redress. They consist of civilians, rather than sworn police officers, as a means to provide an external check mechanism to police department internal affair units. They vary in structure and power, ranging from only making recommendations to police directors about disciplinary action to having the power to subpoena officers. The first civilian review board in the USA was enacted in Washington, DC in 1948, and today, well over 100 review boards exist across the country.23–25 Though evidence on the effectiveness of review boards is mixed, there is some agreement that if they are well resourced, they provide a forum for grievances that can improve police-community relations.23,24,26 Civilian review proposals have faced strong political opposition from police unions over the last several decades.25,27 Most proposals in the 1960s were defeated, but by 1992, police departments in 34 of the 50 largest US cities had some form of civilian review in place.25

Existing research attributes the surge in police oversight mechanisms between the 1970s and early 2000s (from about 13 in 1980 to more than 100 in 2000) to increased public recognition of racial profiling and police misconduct, which drove policy changes through processes such as referenda and city council legislation.24 However, in Newark, where municipal political power has long shifted in favor of groups desiring police reforms, the city failed to adopt a Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) until April 2015.

This study traces the long struggle to enact civilian review in Newark, analyzing the historical arc of this movement for change. I aim to describe which historical events preceded this recent policy adoption and to generate theories as to which local and national factors appeared to make this change possible. In the current national political climate, where advocates and policymakers search for politically feasible reform measures on policing, the Newark case can provide an example for a path to change.

Methods

The site of study, Newark, New Jersey, is a postindustrial city in the New York metropolitan area with a population of over 278,000.28 It is the largest city in the state, with a major international airport, a seaport, and a train station; yet a crippling poverty rate (29 %) persists in the backdrop.28 Newark has an African American population of about 53.9 % and a Hispanic or Latino population of approximately 33.9 %.4

For the present study, a mixed-methods design was used, including qualitative interviews, historical news analysis, and a review of relevant public health literature, to trace the role of grassroots actors, elected officials, federal and state officials, and the police in the evolution of the CCRB policy proposal in Newark. Between April 9 and May 12, 2015, I conducted semi-structured interviews with ten key stakeholders in the Newark CCRB debate. The Princeton University Institutional Review Board approved the interview protocol, and all research participants provided written informed consent to participate.

The criteria used to select key informants required that interviewees were familiar with the political process leading to the conception and enactment of the CCRB. I recruited participants by first reaching out to member organizations of the Newark Communities for Accountable Policing (N-CAP) coalition, city councilors, and police leadership and was referred to additional key informants via snowball sampling. Of the ten key informants, two were elected officials, two were current or retired police officers, and seven represented local, state, or national advocacy organizations closely involved in the CCRB campaign.2 Interviews lasted between 30 and 120 min, and interviewees were asked open-ended questions about the immediate circumstances leading to the passage of the CCRB, the political history of the proposal in Newark, and to identify what they viewed as the primary reasons the CCRB became politically viable at the current moment. Interview transcripts and notes were analyzed using thematic content analysis and constant comparison throughout the data collection and analysis process.29–31 Each transcript was manually coded using categories that corresponded to the interview guide, and coded transcripts were juxtaposed and compared to capture emerging themes.

To contextualize interviewee accounts, I also analyzed news media coverage of the civilian review board debate by searching digital archives of the Newark-based New Jersey Star-Ledger and of the New York Times from 1960 to the present.3 Stories were selected using the search terms “civilian review board” and “civilian complaint review board,” a query that yielded 1829 stories in the New York Times and 179 in the New Jersey Star-Ledger. Search results that were repetitive or referred to civilian review of nonpolice entities (i.e., the military) were omitted from the sample. News articles directly related to Newark (n = 88) were closely read and analyzed to historicize the local CCRB debate, construct a detailed event sequence, and identify key players over time.

Results

Police Violence and Civilian Review in Newark: 1960s to the Present

By most accounts, police-community tensions in Newark peaked in July of 1967, after taxi driver John Smith was beaten and dragged into a police station by Newark police officers. This event sparked a 5-day uprising that ultimately resulted in 26 deaths, 24 of whom were African American civilians and most were killed by police firearms. Long before the bloodshed that summer, the 1957 Mayor’s Commission on Intergroup Relations and local African American newspapers reported assertions of widespread mistreatment of black Newarkers by police.1,32

In Newark, grassroots demands for civilian review first peaked in the 1960s, during local and national debates on police brutality and civil rights (Table 1).33–35 Both before and after the 1967 rebellion, Newark activists took cues from other US cities, including Philadelphia and New York, which began to consider and adopt civilian review boards in the 1950s and 1960s.25,27,36 The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and poet and activist Amiri Baraka were key figures demanding a CCRB in Newark in the early 1960s.1,37,38 However, a CCRB was blocked by opposition from the police force and the powerful unions supporting them.33 In spite of multiple demonstrations and activist demands, Italian-American mayor Hugh Addonizio aligned with the Police Director and the Newark Police Benevolent Association and firmly opposed civilian review.33 When the statewide Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder pushed for the creation of a review board in Newark after the 1967 rebellion, Addonizio remained “unalterably opposed”.34 The political landscape in Newark has long been characterized by racial/ethnic divisions, and during Addonizio’s term, an overwhelmingly white police force patrolled a city that was shifting demographically, with an influx of African Americans migrating from the US South, along with “white flight” from the city.28,39

TABLE 1.

Key local and national events in the political history of civilian review board proposals in Newark, NJ

| 1960s | 1970s–1980s | 1990s–2005 | 2006–2013 | 2014–present | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal: activists and interest groups | 1962-First calls for Civilian review by CORE and Amiri Baraka 1967 Newark Rebellion; Black Power Conference and 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Convention in Newark Police Unions oppose CCRB |

Advocates demand: Civilian review and black police director. Broad community control of institutions. |

Renewed calls for Civilian Review in 1992 through late 1990s Police Unions oppose CCRB; turn backs on mayor 1993: Black Nia Force demands civilian review board |

Continued calls for Review ACLU-NJ initiates investigation into NPD policing (2010) |

Formation of Newark Communities for Accountable Policing (N-CAP), 2014 N-CAP members collaborate with Mayor to design CCRB. Police Unions (FOP and PBA) oppose CCRB |

| Municipal: elite-level politics | Mayor Hugh Addonizio “unalterably opposed” to CCRB 1968-Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder recommends review board in Newark |

Kenneth Gibson, first black mayor, does not pursue CCRB | Mayor Sharpe James endorses CCRB, then backs away. Ras Baraka’s first mayoral campaign includes CCRB 2003: Newark city councilors hold hearings on CCRB |

Mayor Cory Booker’s administration gives unclear support for CCRB Garry McCarthy, Police Director, brings broken windows policing DOJ starts investigation of NPD (2011) |

Ras Baraka elected mayor, May 2014 DOJ Investigation of NPD Report Released, July 2014 “Agreement in Principle” between Newark & DOJ |

| National context | Urban rebellions across country sparked by police violence Civil Rights and Black Power Movements |

Backlash against civil rights policies Growth in “law and order” politics among conservatives. |

Rodney King beating in LA revives national police brutality debate | #Black Lives Matters formed in 2013 | National momentum for criminal justice reform; with police-perpetrated killings in Ferguson, Staten Island, Charleston, Baltimore |

| Federal policy changes | Civil Rights Legislation | Adoption of social welfare retrenchment policies and War on Drugs. | 1994 Violent Crime Act; also allows DOJ to conduct “pattern or practice” investigations of police departments 1999: DOJ begins federal oversight of NJ State Troopers |

Increased “pattern or practice” Investigations conducted by DOJ | Task Force on 21st Century Policing established by President Barack Obama |

Increased black political engagement, and the desire to unseat Addonizio, brought about the election of the first black mayor of any large northeast city, Kenneth Gibson in 1970.1,34,38 Under Gibson, who was politically moderate, racial and gender diversity increased among the police force, but a civilian review board was never passed nor was a black police director initially appointed, the main demand of civil rights activists. At this point, many activists, who played an important role in Gibson’s election, became disillusioned by the limits of black politicians to reform policing practices.40

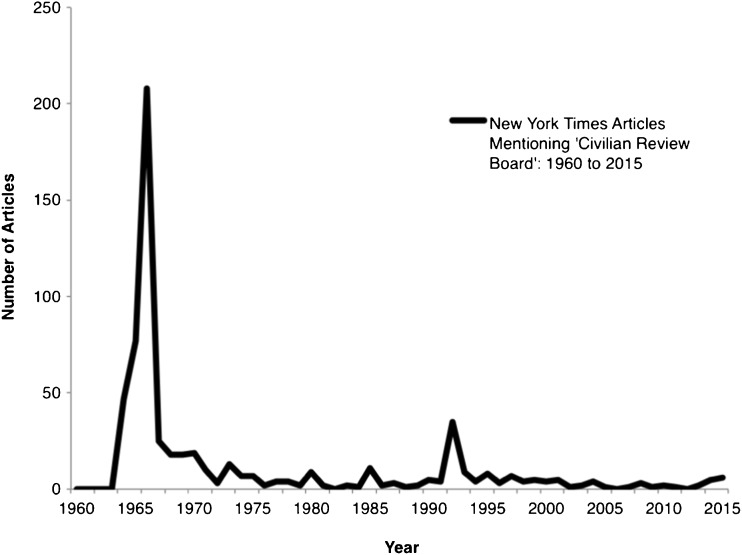

In the early 1990s, Newark activists, fueled by local and national instances of police violence, renewed demands for civilian review. In 1992, after two young people in stolen cars were killed by Newark police, Amiri Baraka, who led the Coalition to End Police Violence, along with the Newark-based People’s Organization for Progress, demanded a civilian review board with subpoena power.41,42 Nationally, a major debate on police brutality swept the USA when the videotaped March 1991 beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles made headlines.43 This period marked the next peak in debates on civilian review (Fig. 1). Locally, activists felt that a civilian review board was possible under then-mayor Sharpe James, an African American from Newark’s South Ward. In 1997, Mayor James publicly endorsed a civilian review board but eventually retracted in the face of opposition from the police.37

FIG. 1.

Number of articles mentioning “civilian review board” in New York Times from 1960 to May 2015. Data retrieved from NYT Chronicle, http://chronicle.nytlabs.com.

Under James’ successor, Cory Booker, grassroots pressure continued and Newark city councilors spearheaded legislative efforts supporting civilian review, but it never gained clear support by the mayor.44 When interviewed by the media, the mayor and police director gave mixed messages on whether a CCRB would be adopted.35 The New Jersey State Police came under a 10-year federal monitor in 1999 due to widespread racial profiling in traffic stops on the New Jersey Turnpike, but Booker believed federal oversight was extreme for the NPD.45,46 Further, Booker’s appointment of white police director Garry McCarthy, from New York City, also upset a delicate equilibrium of race relations in Newark.35,47–49 The Booker administration made police stop-and-frisk data transparent in 2013, but with respect to civilian oversight, a lack of sufficient support from the mayor and police prevented its adoption.

On April 30, 2015, Mayor Ras Baraka signed executive order MEO-15-0005 establishing a civilian complaint review board in the city of Newark. Once implemented, it will be the only civilian review board in New Jersey. Advocates argue that it will be stronger than most existing boards because it will have subpoena power and will require the NPD to consult with the CCRB to create a matrix guiding disciplinary actions for police misconduct.50

Several themes emerged through the analysis to explain why this historical moment allowed for the passage of a review board. These explanations include: (1) the pivotal role of federal intervention by the Department of Justice, (2) the Mayor’s own activist background and his alignment with community advocates, and (3) the presence of a national social movement calling for policing reform.

The Role of Federal Intervention

The July 2014 release of the DOJ’s Investigation of the Newark Police Department proved to be a critical juncture in the evolution of the CCRB. The impetus for the federal investigation was driven by the cooperation of local groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union of NJ (ACLU-NJ). In 2010, the ACLU-NJ petitioned the DOJ for an investigation of the NPD after gathering evidence that a curiously small percentage of complaints made against law enforcement (1 out of 261) were sustained through internal review and that a disproportionate share of victims of police misconduct were black.51 After a nearly 3-year investigation, the DOJ report confirmed widespread rights violations by the NPD, called for fundamental reforms of the department, and initiated the negotiation of a consent decree governing this process. At this moment, local and state advocates formed the Newark Communities for Accountable Policing (N-CAP), realizing the potential to break years of institutional resistance to reforming the NPD. One interviewee reflected:

We thought that this was really the moment because of the DOJ thing. And it’s true that that forced [Baraka] to acknowledge this issue in a deeper way because the federal government was literally having sit-downs with him trying to come up with a consent decree. – Representative of Local Advocacy Organization

Indeed, the federal presence in the city demanded the newly elected mayor’s time in spite of the many competing items on his agenda. It also forced the NPD and police leadership to recognize that change was approaching. An N-CAP member responded decisively, “Look, there wouldn’t be a review board today if the Justice Department had not come in.” These sentiments highlight that the federal investigation shone a light on the activities of the NPD, providing evidence for activists and the mayor to initiate change in the department.

The introduction of the executive order also supports the importance of the DOJ investigation, as the EO refers extensively to the “Agreement in Principle” between the City of Newark and the DOJ before outlining the provisions of the board.50 Thus, it is clear that advocates and the mayor leveraged the legitimacy of federal evidence-gathering to pass this historically controversial policy.

The Activist Mayor

The personal convictions of Mayor Baraka also played an important role in his decisive action to pass this policy. Ras Baraka’s activist background, and the influence of his late father, Amiri Baraka, rendered the mayor personally invested in the passage of a CCRB. Before entering politics, Ras Baraka organized against police brutality as a community activist, and as head of the Newark racial justice organization Black Nia Force.52 When Baraka first ran for mayor in 1994, he championed the establishment of a strong civilian review board in his electoral campaign.53 Multiple interviewees expressed that Mayor Baraka’s proposal goes above and beyond the DOJ’s requirements, reflecting the mayor’s personal commitment to addressing the issue of policing.50

I just know this: that a different mayor may not have responded in as potent a manner. And Ras Baraka responds that way because of the history of his family. Because of himself. Because of his own commitments. He comes out an activist family, and out of an activist tradition. - Representative of Local Advocacy Organization

Baraka’s intimate connections to communities in Newark, forged through his own history of activism, facilitated his alignment with advocates on this issue. Several members of the “community,” as referenced in the EO, were actively involved in crafting the review board. These community members included representatives of the N-CAP coalition who met frequently with the Mayor, as well as the general public who were invited to contribute ideas in a 30-day period of public comment and at a public hearing. Baraka was able to leverage this broad community support to pass the CCRB through executive order, which does not require approval of the legislative council. One city councilor remarked:

So, [the community] trusts Ras Baraka… Ras is perceived as a native son, and because of that they’re willing to give him the opportunity… to experiment with this idea and with this concept. –Member of the Newark City Council

City legislators also appeared to support the Mayor’s initiative, as the municipal council members interviewed for this study expressed their own endorsement of the board and voiced that the council, as a whole, was supportive. The council’s support would aide in codifying the CCRB into law in the future by passing it through the city council as an ordinance. This would prevent the CCRB from being overturned by the next mayor, which occurred in Philadelphia in 1969.24

Finally, Baraka’s well-publicized view of violence as a public health issue seemed to connect him ideologically with advocates seeking broader systemic change as a means to address police violence. As a city councilman, Baraka sponsored anti-violence legislation that recognized violence as a public health emergency, reflecting his expressed belief that crime and violence stem from the “circumstances of a place” and not just individuals.54,55 A representative of an N-CAP organization agreed with the public health lens, remarking:

I think Baraka’s philosophy is very important on policing because he looks at policing as a public health issue… That a lot of crime, which I believe, is a symptom of other things, like poverty, educational inequity. So, his thing is that we’re gonna address the root of this. Policing is just a Band-Aid in a lot of ways to actual structural issues in communities. – Representative of State Advocacy Organization

This framing of violence, including police violence, as symptomatic of other social ills, placed the mayor and community advocates in alignment on the need for systematic change. This convergence of views in Newark in 2015 coincided with a national movement that was calling greater attention to police killings of African Americans as a product of institutionalized racism.

Leveraging a National Movement

The ongoing national movement against police violence and anti-black racism, Black Lives Matter, played no small part in lending credibility to the local movement in Newark. An interviewee representing an advocacy organization described the current moment as the “national momentum for policing reform,” wherein events in Ferguson, Staten Island, and a growing list of locales, have hoisted policing reform onto government agendas. At the press conference in Newark City Hall where the Mayor signed the executive order, Baraka made several references to cases in Baltimore, Ferguson, and Charleston, South Carolina. He said:

We’re here because people get shot in the back eight times while they’re running away from the police. We’re here because people can be choked to death on the street while saying that they can’t breathe. We’re here because people can get their spines severed and their throats crushed in custody and we still have a question about what actually took place. That’s why we’re here.56 - Mayor Ras Baraka

With these words, Baraka invoked the national outrage about the police killings at the forefront of American public debate. He drew on stories that dominated the news cycle to lend his policy decision a sense of urgency and credibility. As Baraka unapologetically expressed that he did not have to negotiate with police unions to write this policy, he simultaneously argued that he was working in the interest of the larger public and that that public is in a state of emergency. These appeals served as justifications for the passage of a strong board through executive action and despite the grievances of police unions.

Discussion

The case of the Newark CCRB demonstrates that even in the face of political opposition, a controversial policing reform can be passed. This study generated hypotheses as to how political shifts and national interventions yield opportunities for policing reforms which may have reverberating impacts on population wellbeing.57 With the growing recognition of policing’s impact on public health, health care professionals, public health leadership, and physicians-in-training have joined calls for policy reforms.58–60 These calls, which include an acknowledgement of the role of racial discrimination in health outcomes, exist alongside several old, and new, policy proposals to eliminate police brutality in the USA. Racial discrimination, including racial profiling, and the stress that accompanies it has been linked to higher levels of chronic disease and mental illness among African Americans.22,61–64 One pathway by which people of color may “embody discrimination” and its effects on long-term health is through “socially inflicted trauma,” which includes stressful “verbal to violent” encounters with individuals or with the society at large.63 Recent epigenetics research also connects environmental stressors, including discrimination, to increased risk of cardiovascular illness, low birth weight and other conditions, which may have intergenerational effects.65 Thus, an intervention that reduces the stress of racial profiling and discriminatory policing can have lasting health benefits for populations most at risk.

Taken together, the politics, laws, and policies that govern the operations of law enforcement can be said to comprise the “political determinants of health”.16 That is, the relationships of power that produce the everyday aggressions that marginalized communities experience lie among the upstream predictors of health and wellbeing in these populations.16,63,66 Police accountability reform can be compared to other policy changes that have targeted nonhealth-specific actors for public health gains. For example, the New York Police Department’s May 2014 announcement to end police confiscation of condoms for use as evidence in prostitution cases was a change driven by human rights advocates to end a practice that disproportionately targeted transgender women and groups frequently suspected of sex work.17 Additionally, pressure from the DOJ, the ACLU and Human Rights Watch led to the recent desegregation of HIV positive prisoners in South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi, ending a discriminatory practice that lacked scientific basis.67 Thus, strategies employed to disrupt the status quo political determinants of health—including grassroots activism and petitioning for DOJ intervention—may have direct and indirect public health impacts.

If the Newark CCRB, in fact, lowers rates of police misconduct and racial profiling, one driver of adverse health consequences will be diminished. Moreover, establishing a mechanism for communities to monitor police forces can, in itself, improve community health through increased citizen self-efficacy. Indeed, the presence of a board provides a mechanism for control over one’s life that previously did not exist. Because institutionalized racism manifests through a lack of access to power, or a lack of autonomy, community organizing and increased political clout can have a protective effect for populations that are discriminated against.63,66 Thus, by elevating civilian voices in adjudicating cases of police misconduct—where victims and their families often feel tremendously disempowered—cities adopting CCRBs may indirectly improve health and reduce disparities. Finally, at a systems level, the simple act of tracking police misconduct brings police-civilian interactions into the realm of scientific study, promoting greater understanding of the circumstances surrounding excessive police force. Given the dearth of data on police killings, any entity which monitors and tracks police misconduct would help to fill this gap.8

Conclusion

In Newark, a federal investigation, combined with the election of an activist mayor at the cusp of a national movement against police brutality, made way for a policy proposal that had been attempted in Newark since the 1960s. Though this study cannot isolate a single pivotal driver of reform, it sheds light on how local advocates and politicians strategically leveraged national and local resources to pass civilian review. As jurisdictions across the country grapple with how to improve police-community relations, additional studies may further reveal how federal resources, local advocates, and elected officials have overcome seemingly intractable political obstacles to policing reforms.

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to thank the study participants for their generous contributions to this research. I would also like to thank my friends, and my colleagues at Princeton University’s Center for Health and Wellbeing, for their feedback and editorial assistance.

Footnotes

The literature and popular news media describe the 1960s events as “riots,” “rebellions”, and/or “uprisings.” In this paper, I use the terms uprising and rebellion interchangeably.

One interviewee fell into two categories.

Electronic archives of the New Jersey Star-Ledger were available starting in 1989.

References

- 1.Curvin R. Inside Newark: decline, rebellion, and the search for transformation. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodard K. A nation within a nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power politics. 1. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACLU-NJ. U.S. Department of Justice investigation finds widespread constitutional violations by Newark Police Department. July 2014. https://www.aclu-nj.org/news/2014/07/22/us-department-justice-investigation-finds-widespread-constit. Accessed May 8, 2015.

- 4.United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, United States Attorney’s Office District of New Jersey. Investigation of the Newark Police Department. July 2014. http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/spl/documents/newark_findings_7-22-14.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2015.

- 5.Fischer-Baum R, Johri A. Another (much higher) count of homicides by police. FiveThirtyEight. August 2014. http://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/another-much-higher-count-of-police-homicides/. Accessed August 4, 2015.

- 6.The Counted: people killed by police in the United States in 2015—interactive. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/the-counted-police-killings-us-database. Accessed August 6, 2015.

- 7.Fatal Encounters. Fatal Encounters. http://www.fatalencounters.org/. Accessed August 6, 2015.

- 8.Lowery W. How many police shootings a year? No one knows. The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2014/09/08/how-many-police-shootings-a-year-no-one-knows/. Published September 8, 2014. Accessed June 1, 2015.

- 9.Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. Characterizing perceived police violence: implications for public health. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1109–1118. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fullilove MT, Héon V, Jimenez W, Parsons C, Green LL, Fullilove RE. Injury and anomie: effects of violence on an inner-city community. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):924–927. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.6.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DR, Williams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: the African American experience. Ethn Health. 2000;5(3–4):243–268. doi: 10.1080/713667453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerr T, Small W, Wood E. The public health and social impacts of drug market enforcement: a review of the evidence. Int J Drug Policy. 2005;16(4):210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, Alexson D, Gibson K, Tyndall MW. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental–structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ofer U, Rosmarin A. Stop-and-frisk: a first look. February 2014. https://www.aclu-nj.org/files/8113/9333/6064/2014_02_25_nwksnf.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2015.

- 15.Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. The impact of a police drug crackdown on drug injectors’ ability to practice harm reduction: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(3):673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amon JJ. The political epidemiology of HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014; 17:19327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Amon JJ, Wurth M, McLemore M. Evaluating human rights advocacy on criminal justice and sex work. Health Hum Rights J. 2015;17(1):E91–E101. doi: 10.2307/healhumarigh.17.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wurth MH, Schleifer R, McLemore M, Todrys KW, Amon J. Condoms as evidence of prostitution in the United States and the criminalization of sex work. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013; 16: 18626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Davis CS, Burris S, Kraut-Becher J, Lynch KG, Metzger D. Effects of an intensive street-level police intervention on syringe exchange program use in Philadelphia Pa. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):233–236. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beletsky L, Heller D, Jenness SM, Neaigus A, Gelpi-Acosta C, Hagan H. Syringe access, syringe sharing, and police encounters among people who inject drugs in New York City: a community-level perspective. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beletsky L, Agrawal A, Moreau B, Kumar P, Weiss-Laxer N, Heimer R. Police training to align law enforcement and HIV prevention: preliminary evidence from the field. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):2012–2015. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller J, Cybele M. Civilian oversight of policing: lessons from the literature. Vera Institute of Justice; 2002. http://www.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/Civilian_oversight.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- 24.Walker S. The history of civilian oversight. In: Perino JC, editor. Citizen Oversight of Law Enforcement: Legal Issues and Policy Considerations. Chicago: American Bar Association; 2006.

- 25.Walker S, Bumphus VW. Effectiveness of civilian review: observations on recent trends and new issues regarding the civilian review of the police. Am J Police. 1992;11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker S. Complaints against the police: a focus group study of citizen perceptions, goals, and expectations. Crim Justice Rev. 1997;22(2):207–226. doi: 10.1177/073401689702200205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudson JR. The civilian review board issue as illuminated by the Philadelphia experience†. Criminology. 1968;6(3):16–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1968.tb00195.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Census Bureau. State and County QuickFacts. U S Census Bur State Cty QuickFacts. April 2015. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/34/3451000.html. Accessed May 22, 2015.

- 29.Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith CP. Motivation and personality: handbook of thematic content analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1992.

- 31.Boeije H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual Quant. 2002;36(4):391–409. doi: 10.1023/A:1020909529486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chester R, Grier E, Grier G. Group Relations in Newark- 1957: problems, prospects and a program for research. New York City: Urban Research; 1957.

- 33.Newark divided on police tactics: proposed civilian review becomes major issue. The New York Times. August 8, 1965:60.

- 34.Waggoner WH. Newark mayor bars police review board. The New York Times. February 29, 1968:1.

- 35.Queally J. Timetable unclear for Newark cop review panel—Booker, police director offer a mixed message. The Star-Ledger. March 31, 2013:021.

- 36.Bartels EC, Silverman EB. An exploratory study of the New York City civilian complaint review board mediation program. Polic Int J Police Strateg Manag. 2005;28(4):619–630. doi: 10.1108/13639510510628703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onley DS. James endorses civilian board to monitor cops. The Star-Ledger. July 2, 1997:45.

- 38.Mumford K. Newark: a history of race, rights, and riots in America. New York: NYU Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Census Bureau. 20th Century Statistics. In: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1999. 118th ed. Washington, D.C. https://www.census.gov/prod/99pubs/99statab/sec31.pdf.

- 40.Kelley RDG. Freedom dreams: the black radical imagination. New edition edition. Boston: Beacon Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nieves E. Newark police shootings revive calls for a civilian review board. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/11/nyregion/newark-police-shootings-revive-calls-for-a-civilian-review-board.html. Published September 11, 1992. Accessed May 9, 2015.

- 42.Carter B. Newark activists demand election of civilian board to review police. Star-Ledger, The (Newark, NJ). http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/12246EBC6B81D140?p=AWNB. Published September 11, 1992. Accessed May 19, 2015.

- 43.Ralph L, Chance K. Legacies of fear: from Rodney King’s beating to Trayvon Martin’s death. Transition. 2014;113(1):137–143. doi: 10.2979/transition.113.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mays JC. Newark to revisit review board—hearing will explore oversight measure. The Star-Ledger. January 17, 2008:25.

- 45.The Associated Press. Judge Ends Federal Oversight of New Jersey State Police. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/22/nyregion/22profile.html. Published September 21, 2009. Accessed September 20, 2015.

- 46.Queally J. Newark police to be monitored by federal watchdog, sources say. The Star-Ledger. http://www.nj.com/essex/index.ssf/2014/02/justice_department_will_place_federal_monitor_over_newark_police_sources_say.html. Published February 9, 2014. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- 47.Jacobs A. White police chief could upset a balance in Newark. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/15/nyregion/15police.html. Published August 15, 2007. Accessed May 19, 2015.

- 48.Mack K. Rahm Emanuel is set to name Garry McCarthy new Chicago police superintendent Monday, source says. Chicago Tribune. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2011-05-01/news/ct-met-garry-mccarthy-chicago-police-20110501_1_chicago-veterans-chief-patrol-eugene-williams-deputy-superintendent. Published May 1, 2011. Accessed May 29, 2015.

- 49.Sanburn J, Kluger J. New York Police Chief Defends “Broken Windows” Policing. Time. 00:39, −05-29 17:48:00 2015. http://time.com/3842628/nypd-bill-bratton-broken-windows/. Accessed May 29, 2015.

- 50.City of Newark. Executive Order No.: MEO-15-0005.; 2015. http://www.ci.newark.nj.us/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/ExecutiveOrder-CivilianComplaintReviewBoardwithRules_FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2015.

- 51.ACLU-NJ Report reveals troubling use of stop-and-frisk in Newark. Am Civ Lib Union. https://www.aclu.org/news/aclu-nj-report-reveals-troubling-use-stop-and-frisk-newark. Accessed May 8, 2015.

- 52.Garrett R. A stand against brutality. Star-Ledger, The (Newark, NJ). http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/12247241151458D8?p=AWNB. Published February 22, 1993. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- 53.Kukla B. Voters head for the polls tomorrow to elect a mayor and city council. Star-Ledger, The (Newark, NJ). http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/122487C3EEBA72B8?p=AWNB. Published May 9, 1994. Accessed May 19, 2015.

- 54.Demands | Newark anti-violence coalition. http://www.navcoalition.org/demands/. Accessed August 21, 2015.

- 55.Ivers D. Newark rolls out plans to rehabilitate two blight, crime-ridden neighborhoods. NJ.com. http://www.nj.com/essex/index.ssf/2014/11/newark_rolls_out_rehabiliation_plans_for_two_blight_crime-ridden_neighborhoods.html. Accessed September 15, 2015.

- 56.Ivers D. With stroke of a pen, long-awaited civilian review board becomes reality in Newark. NJ.com. http://www.nj.com/essex/index.ssf/2015/04/baraka_signs_order_creating_civilian_board_to_revi.html. Accessed May 8, 2015.

- 57.Russell GD. The political ecology of police reform. Policing. 1997;20(3):567. doi: 10.1108/13639519710180231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bassett MT. #BlackLivesMatter—a challenge to the medical and public health communities. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12):1085–1087. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.American Public Health Association. Impact of Police Violence on Public Health. January 1998. http://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/11/14/16/impact-of-police-violence-on-public-health. Accessed May 23, 2015.

- 60.Committee of Interns and Residents SEIU. SFGH Resident Statement Against Police Brutality. http://www.cirseiu.org/2014/12/10/statement-against-police-brutality/. Accessed May 23, 2015.

- 61.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams DR, Sternthal M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health sociological contributions. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1 suppl):S15–S27. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krieger N. Discrimination and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000:36–75.

- 64.Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv Plan Adm Eval. 1999;29(2):295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuzawa CW, Sweet E. Epigenetics and the embodiment of race: developmental origins of US racial disparities in cardiovascular health. Am J Hum Biol. 2009;21(1):2–15. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.ACLU Prison Project, Human Rights Watch. Sentenced to Stigma: Segregation of HIV-Positive Prisoners in Alabama and South Carolina.; 2010. https://www.hrw.org/report/2010/04/14/sentenced-stigma/segregation-hiv-positive-prisoners-alabama-and-south-carolina. Accessed September 21, 2015.