Abstract

Facilitating human–carnivore coexistence depends on the biophysical environment but also on social factors. Focusing on Central Romania, we conducted 71 semi-structured interviews to explore human–bear (Ursus arctos) coexistence. Qualitative content and discourse analysis identified three socially mediated thematic strands, which showed different ways in which perceived interactions between people, bears and the environment shape coexistence. The “landscape-bear strand” described perceptions of the way in which the landscape offers resources for the bear, while the “landscape-human strand” related to ways in which humans experience the landscape. The “management strand” related to the way bears was managed. All three strands highlight both threats and opportunities for the peaceful coexistence of people and bears. Management and policy interventions could be improved by systematically considering the possible effects of interventions on each of the three strands shaping coexistence. Future research should explore the relevance of the identified thematic strands in other settings worldwide.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13280-015-0760-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Brown bear, Carnivore conservation, Conflict mitigation, Human–carnivore conflict, Human–nature relationships

Introduction

Where humans and large carnivores share the same landscape, there are inevitable conflicts. For example, humans can experience attacks and predation on livestock, with resultant economic impacts (Thirgood et al. 2005; Holmern et al. 2007), and carnivore populations decline as a result of persecution and growing human pressure on carnivore habitat (Woodroffe 2000; Ripple et al. 2014). Therefore, successful carnivore conservation depends not only on the biophysical environment but also on understanding the social factors that shape human–carnivore coexistence (Treves and Karanth 2003). Importantly, human tolerance towards carnivores is not only shaped by the experience of damage (Hazzah et al. 2009; Dickman et al. 2014; Kansky et al. 2014). Rather, it is constructed through a variety of factors related to economic, aesthetic, ecological, cultural, religious, and intrinsic values ascribed to carnivores (Zinn et al. 2000; Dickman 2010). For example, traditional and cultural differences between pastoralists and agriculturalists explain differences in tolerance towards lions in South Africa (Gusset et al. 2008; Lagendijk and Gusset 2008). Moreover, the political environment also can influence human–carnivore interactions, for example, through the implementation of top-down conservation management, financial incentives, or legislation (Redpath et al. 2012), which may clash with the priorities of rural populations (Skogen et al. 2008; Majic et al. 2011).

To design effective tools that facilitate coexistence, studies need to account for the complexity of social factors that shape it (Dickman 2010). Despite an increasing recognition of the need to integrate social science into understanding the extent of human–carnivore conflicts (Carter et al. 2012; Inskip et al. 2014), the majority of studies to date have described conflicts or attitudes towards carnivores, whereas fewer studies have focused on the underlying drivers and impacts of conflict (Barua et al. 2013; Can et al. 2014; Madden and McQuinn 2014). In Europe, such knowledge is particularly important because recent expansions of brown bear (Ursus arctos) populations have caused increased conflicts (Enserink and Vogel 2006; Can et al. 2014), and illegal killing could undermine the recovery of bear populations (Ciucci and Boitani 2008; Kaczensky et al. 2011). To understand coexistence, regions where humans and carnivores have successfully co-occurred for a long time could provide particularly useful case studies (Boitani 1995).

In this paper, we propose a new concept, namely that of “strands of coexistence”. We define a strand of coexistence as a socially mediated set of mechanisms by which human–wildlife coexistence can be either facilitated or hindered. Our approach was informed by a discourse-driven analysis. With its explicit focus on local perceptions, discourse analysis is suited to explore and reveal how perceptions of coexistence are shaped by underlying factors of social context, cultural patterns, beliefs, and values (Mattson and Clark 2012; Bixler 2013). This type of analysis provided a deeper understanding into people’s different perspectives on coexistence than more deductive approaches, and as such filled an important gap in the literature: As we detail below, the concept of coexistence strands is grounded in the perceptions of local people, and thus provides a means of disentangling the subjective realities experienced by people living with carnivores. We further show that each strand provides a lens for examining different threats and opportunities for the management of human–carnivore coexistence. This, in turn, is likely to be of substantial applied value for the development of locally relevant policy and management measures.

Our study focused on the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains in Transylvania, Romania. Here, people and bears have co-occurred for extended periods of time, and the close proximity of forest, villages and farmland, as well as the reliance of people on forest products (e.g. firewood), provides ample opportunities for human–bear interactions. Furthermore, traditional practices such as shepherding and bee keeping are potential areas of conflict with bears (Zedrosser et al. 2001). We explored factors underlying people’s perceptions of coexistence and, based on this, identified three socially mediated strands of coexistence. We discuss the relevance and heuristic value of these thematic strands to guide future research and management.

MATERIALS AND Methods

We primarily used an inductive approach to generate insights on human–bear coexistence (see also Inskip et al. 2014), rather than a deductive approach to test specific theories or hypotheses (Pratt 2009). We conducted 71 semi-structured, qualitative interviews to explore the social factors mediating human–carnivore coexistence. All interviews took place within 50 km of the town of Sighişoara in Southern Transylvania. We aimed to interview 3–4 people per village in a total of 20 villages. We selected the 10 villages with the highest and 10 with the lowest perceived human–bear conflicts as indicated by previous research (Dorresteijn et al. 2014) to ensure a broad range of responses to perceived coexistence. People were asked randomly in the street or in local shops if they were interested in participating in the interview. In addition to local people, we also purposefully interviewed shepherds, foresters, and hunters. The themes covered by the interview guide related to people’s experiences with bears, knowledge and perceptions of living with bears, general attitudes and values, and bear management (Appendix S1). Although the interviews were guided, we allowed for discussions on unanticipated themes. All interviews were conducted by a local Romanian and Hungarian speaker, recorded, and later transcribed and translated into English.

We analysed the interview transcripts by first grouping all interview participants into three groups regarding their overall perception of human–bear coexistence (positive, negative, neutral). For ease of communication, we only show the results for people with positive or negative perceptions. We applied qualitative content and discourse analysis by coding the transcripts for themes using NVivo 10 (QSR International Pty ltd 2012). Content analysis was conducted for directly reported themes, such as those covered in the interview guide. To elucidate aspects of the relationship between wildlife and locals that are not immediately obvious from their interviews, the perspective of discourse analysis was also applied to interrogate the data for unprompted or underlying themes, as previously applied in conservation biology (Gray et al. 2008; Bixler 2013). Coding cycles were iterative. Themes were increasingly aggregated into higher levels of abstraction, until all text was assigned to three distinct coexistence strands. That is, thematic strands of coexistence emerged from considering themes in the interview guide, but more importantly, were coded inductively from listening to local people’s experiences. As a result, they were directly relevant to the day-to-day realities experienced by people living with bears. Notably, each emerging coexistence strand included both threats and opportunities for the peaceful coexistence with bears. Rather than providing a specific set of management recommendations, each strand thus provides a lens through which interrelated sets of challenges can be examined. This approach, in turn, offers fresh, grounded perspectives on human–carnivore coexistence that are (by definition) relevant to local people.

Following a sociological triangulation approach, we also used quantitative questionnaires (n = 252; Appendix S2) to complement our qualitative findings. These questionnaires were useful to understand broad patterns of coexistence, but semi-structured interviews provided more nuanced insights (Huntington 2000). For this reason, we draw primarily on the qualitative interviews, but recognise the merits of both tools. The specific results of the questionnaires and their implications are presented in Appendix S3.

Results

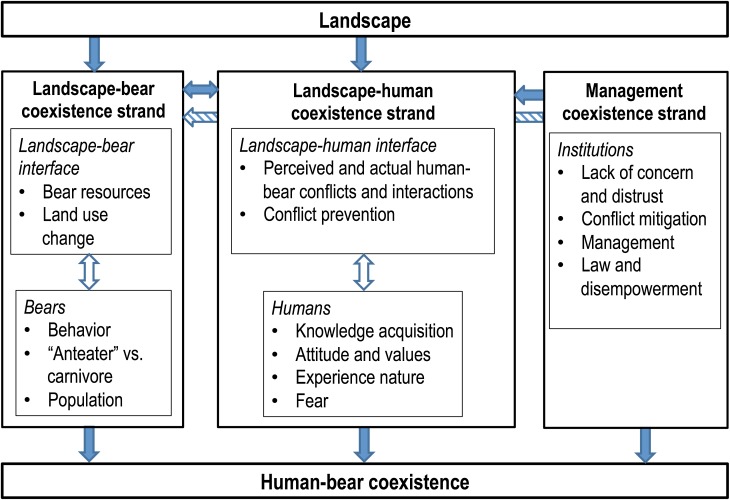

The majority of respondents in the interviews had a positive perception of human–bear coexistence (n = 43; 61 %), whereas 18 people (25 %) had a negative perception, and 10 people (14 %) were ambiguous. Three coexistence strands emerged from iterative coding—a landscape–bear coexistence strand, a landscape–human coexistence strand, and a management coexistence strand. In different ways, each of these showed how people’s attitudes towards different aspects of the landscape, bears, the human community, and management supported or diminished the willingness of local people to live with bears (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework showing three identified coexistence strands based on qualitative content and discourse analysis of 71 interviews. A coexistence strand shows how ongoing interactions between elements of the ecological system and the social system shape people’s perception on human–bear coexistence. Each coexistence strand provides a lens of analysis that can be used to identify threats and opportunities for peaceful human–carnivore coexistence

Landscape-bear coexistence strand

The landscape–bear coexistence strand considered how people viewed the relationship between bears and the surrounding landscape, as well as people’s perceptions of bear behaviour and ecology. Coexistence was supported by people’s understandings of bear behaviour, and hindered by concerns about inadequate bear habitat, deforestation, and increasing bear populations (Table 1). The surrounding landscape played an important role in people’s perception of current and future coexistence. People with a positive perception deemed forest size and food supply in the region sufficient, while people with a negative perception deemed it insufficient (Table 1, row a). Deforestation and land use change were major concerns of both groups because they expected an increase in future conflicts with increasing disturbance to bear habitat (Table 1, row b).

Table 1.

Characterizing quotes for the themes within the landscape–bear coexistence strand. The respondents were grouped into two groups based on their perception of coexistence (positive or negative). The number of people mentioning a given theme is reported and the percentage within each group is given in parentheses. The “P” or “N” behind each quote indicates whether the person had a positive or negative perception of coexistence. Capital letters refer to a given respondent’s ID code

| Landscape–bear coexistence strand | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of coexistence | Characterizing quotes | ||

| Positive (n = 43) | Negative (n = 18) | ||

| a. Bear resources | 17 (40) | 6 (33) | So long as forests remain I don’t think something bad can happen, I don’t think the bear will come down in the village (ALM4; P) As long as it has food in the forest it won’t eat up the people’s potatoes or corn. Then it has no reason to come into the village (SAC2; P) We have only a few, small forests here! There’s no place for the bear to stay there (BLA3; N) |

| b. Land use change | 17 (40) | 4 (22) | The deforestation. Because when you cut away the forests, they [the bears] come to the villages, the more forests you cut away, the less space and silence they have (GRA1; P) I’m thinking about deforestation. You destroy the bears’ habitat. It needs to adapt as well. It can’t hide anymore; it gets more and more in contact with humans, its hunting area disappears and that becomes a problem. This is how the bear may become a problem! (MAL1; N) |

| c. Bear behaviour | 21 (72) | 14 (78) | The bear is not an animal that attacks without being provoked (BLA1; P) The shepherd was always saying: “Hey, the bear is coming, the bear is coming!” [I answered]: “Let it come, man! Let it come” When it comes, it takes [one/a few]… It’s not like the wolf! A wolf, once it jumps into a compound, it kills 4–5–10 sheep, and then it takes one and leaves! But the bear takes one under its arm and leaves (DEA1; N) |

| d. The anteater vs. the carnivore | 12 (28) | 5 (28) | There are only ant-eating bears. They don’t attack the sheep (MAL2; P) Doesn’t matter what point of view we take on them: As long as they eat plants, there’s no problem with them, but once it gets to taste meat, it’ll get aggressive (SAC1; N) |

| e. Bear population | 25 (58) | 12 (67) | No, there aren’t ‘urgent’ problems—it’s just that they appear more and more often! (VAD3; P) Because there are more of them, it attacks animals and man more often! (SAC4; N) We have knowledge about the fact that bears have been brought here. There weren’t that many bears in the past, by far (ALE1; P) It has been brought here. And then it reproduced (VAL3; N) |

The “peaceful” behaviour of bears and the relatively low damage caused by bears compared to other species (e.g. wolf, Canis lupus) were considered important for coexistence across respondents (Table 1, row c). The importance of perceptions of bear behaviour to coexistence was further expressed through the local belief of the existence of two types of bears, namely the primarily vegetarian “ant-eating bear” versus the “carnivorous bear” (Table 1, row d). Coexistence with the ant-eating bear was perceived to be unproblematic, whereas the carnivorous bear was perceived as a dangerous animal. Despite the view of bears being relatively harmless, the perceived increase in the bear population was considered a problem for coexistence (Table 1, row e). Several people mentioned that bears were only present recently, and that they had either come from the mountains or had been brought to the area from overpopulated areas or for hunting purposes (Table 1, row e).

Landscape-human coexistence strand

The landscape–human coexistence strand related to experiential, as well as cognitive and emotional aspects of people’s relationships with the landscape (sensu Chiesura and De Groot 2003). Active experiences with bears and nature (including bear encounters) supported the formation of knowledge and attitudes towards bears, and shaped which non-use and use values (sensu Lindenmayer and Fischer 2006, p. 162) were assigned to bears.

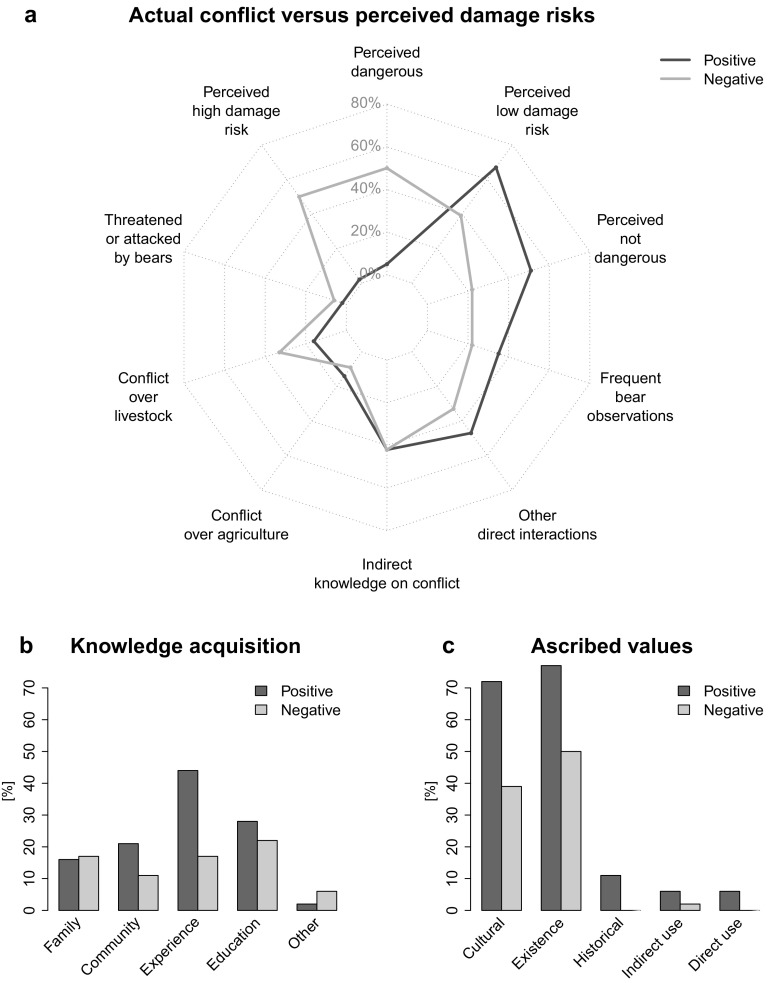

The perception of coexistence was especially positive for people who had positive interactions with bears, while negative perceptions were related to higher livestock predation and higher levels of perceived damage and danger by bears (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, such perceived damages appeared to have more influence on perceptions of coexistence than actual conflict (Fig. 2a). In contrast, crop damage, indirect knowledge of conflicts, and threats or attacks by bears, had little effect on the perception of coexistence (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Human–bear interactions, bear knowledge acquisition, and values ascribed to bears between two groups of respondents—those with a generally positive perception (n = 43) of human–bear coexistence versus those with a generally negative perception (n = 18). a The difference between actual conflicts, bear interactions, and perceived damage risks. The actual conflicts and bear observations were derived from direct questions asked at the beginning of the interview (see Appendix S2), while perceived damage risk, other direct interactions, and indirect knowledge of conflicts were interpreted from the interviews. b Sources where people acquire knowledge on how to live with bears. c Values ascribed to bears. The importance of cultural values was a question in the interview guide (see Appendix S2), whereas all other types of values emerged from the interviews

Education, family, and community members all played a role in acquiring knowledge on how to live with bears, but people with a positive perception mentioned more often that they learned through experience (Fig. 2b). Attitudes towards bears were especially positive for people with a positive perception of coexistence (88 % positive attitude; 0 % negative attitude), compared to people with a negative perception (19 % positive attitude; 28 % negative attitude). Here, non-use values related to the socio-cultural importance people attached to bears and nature. Such non-use values, including cultural, existence, and historical values, were more often associated with bears than use values across all respondents, although these values were more prominent among people with a positive perception (Fig. 2c). Deep and continuous relations between people and nature seemed to be more important to support coexistence than financial incentives or other use values: “Well, for us the bear is like our neighbour, (…) like the neighbour at home. There’s no difference between my neighbour and the bear that comes every second evening. We’re somehow used to it. (VID4)”; “When you love nature I don’t think that you need a lesson, necessarily, to live with them (CIN3)”; “You don’t want to see a dead forest [without animals], right? It’s different when you see a bird on a tree, a bear, a deer. That makes the difference! You see life in nature! Dead nature is like a village without inhabitants (LAS4)”. Fear was one of the emergent themes but was only mentioned by few respondents (afraid: n = 6; not afraid n = 9), without large differences between the two groups.

Management coexistence strand

The management coexistence strand was mediated by the local institutional environment—that is, formal and informal rules and regulations that shape bear management. Institutions for managing bears or the landscape influenced perceptions of coexistence either positively or negatively. The majority of people were dissatisfied with current bear management, mainly due to a lack of concern for their problems with bears, disinterest from the management authorities, distrust towards them, lack of conflict mitigation, and perceived bad management (Table 2). The only 12 people who were satisfied with management believed that the provision of supplemental or divisionary feeding was enough to prevent conflict (Table 2, row c). However, the majority of people believed that authorities and hunting organisations failed to mitigate conflict by not feeding the bears (enough), by not controlling the bear population, and by not providing compensation after damage (Table 2, rows i–k). Furthermore, six people expressed concerns about trophy hunting, indicating that common people carried the burden of living with bears so that hunting organisations could earn money from trophy hunting (Table 2, row l). Although the law and protection status were perceived to aid coexistence by people with a positive perception of coexistence, people with a negative perception viewed laws as artificial tools beyond their power or influence, preventing them from taking care of problem animals themselves (Table 2, rows g and m).

Table 2.

Characterizing quotes for the themes within the management coexistence strand. The respondents were first grouped into two groups based on their perception of coexistence (positive or negative), and second, based on their opinion whether they were satisfied with current bear management. The number of people mentioning a given theme is reported and the percentage within each group is given in parentheses. The “P” or “N” behind each quote indicates whether the person had a positive or negative perception of coexistence. Capital letters refer to a given respondent’s ID code

| Management coexistence strand | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of coexistence | Characterizing quotes | ||

| Positive (n = 11) | Negative (n = 1) | ||

| Satisfied with current bear management | |||

| a. Lack of concern and distrust | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | (Not applicable) |

| b. Conflict mitigation: compensation | 1 (9) | Yes, there is the principle when an animal caused damage, the person affected will be compensated (BLA1; P) | |

| c. Conflict mitigation: feeding | 9 (82) | 1 (100) | Yes, they feed them—the “paznic de vanatoare”. This has been done in the past as well, when they brought them dead animals in a big open pit (CIN1; P) |

| e. Management: control bear population | 1 (9) | I’m against their killing and wiping them out, but I think that their population growth should be controlled a bit, as well as their spreading (CIN3; P) | |

| f. Management: legal and illegal hunting | 6 (55) | Every year we shoot one bear which is pretty ok. That’s the money of the hunting association. They pay something to the state as well. Don’t know if they pay something to the local community (VAN2; P) | |

| g. Law and disempowerment | 5 (45) | They’d almost disappeared and [you can shoot them today] only with a special permit where they cause big damage. The wolf, the wild cat, the bear—they’re all protected (GRA1; P) | |

| Perception of coexistence | Characterizing quotes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 21) | Negative (n = 13) | ||

| Dissatisfied with current bear management | |||

| h. Lack of concern and distrust | 11 (52) | 3 (23) | But they don’t do anything. Nobody cares for nothing! Nothing. I’ve been to the mayor and he said: “Should I come and guard them instead of you?”(VID4; P) A bear is worth four human lives. Yes! Once it has killed four humans, you’re allowed to shoot it. Therefore, it is worth four human lives. (VAL3; N) |

| i. Conflict mitigation: compensation | 5 (24) | 5 (38) | The one who has the damage, stays with the damage. Only when the damage is bigger. Only then. Otherwise nobody cares/makes an effort (ALM1; P) I guard the fields that I have paid for, otherwise the wild animals destroy the harvest and nobody pays me the damage. Nobody pays for it! (…). We don’t have a big production but we’re living of it. The damages aren’t big for them [authorities], but we have to live from this (GHI1; N) |

| j. Conflict mitigation: feeding | 8 (38) | 4 (31) | When there are many bears, they should feed them so they don’t come and attack…I2: They don’t feed them [enough], that’s why they attack! (CRI2; P) They must be fed as well! It’s not enough to let them free in the forest, but to feed them as well. The forest authority has fed them in the past! (PRO3; N) |

| k. Management: control bear population | 3 (14) | 3 (23) | Let the bear population grow but keep it under control (AGA1; P) The population management is a bit out of control. I don’t think there is a true population management. (…) But the true control was in the past the fact that the bears were kept under a certain number/density in a certain area (MAL1; N) |

| l. Management: legal and illegal hunting | 13 (62) | 8 (62) | For the locals it’s just disadvantages, because the hunters are not from this region so that we can say: “We keep the earnings from the hunting!” In case they shoot a bear. The problem is that those who shoot the bears are not locals and the truth is that, as far as I see, they don’t even care for compensating for losses that locals might have (SAC3; P) The management of bears by the state is not working properly. This could be improved—but as long as a hunter may come to shoot a bear for a certain amount of Euros, without caring that this causes to others a double amount of damage or even a human life. We’d need to think about all this! Then bears and humans would get along well (MAD1; N) |

| m. Law and disempowerment | 8 (38) | 5 (38) | How should I say: They could live together. Because you can’t do anything against them! You can’t go into the forest and shoot them. What else can you do, but live next to them (BLA2; P)? A human life is worth more than a bear’s, Sir. Protecting bears is good, but it’s somehow overprotected, Sir (MIH1; N) |

Discussion

By mapping the perceptions underpinning people’s willingness to coexist with bears, our study identified three general strands that appear to influence the coexistence of people and bears in Central Romania. Our qualitative discourse-driven approach (Bixler 2013) generated an understanding of the factors mediating coexistence from the perspective of the rural population and enabled underlying factors to be made explicit, including people’s perceptions of management institutions, bear interactions with the landscape, and human interactions with the landscape. Arguably, such a perspective is particularly important to inform conservation management and foster human–bear coexistence. Moreover, by disentangling, aggregating and conceptualizing social factors as (potentially generic) strands, we provide a conceptual framework that may help to better understand and facilitate human–carnivore coexistence worldwide.

Factors mediating coexistence in Southern Transylvania

The two landscape-mediated coexistence strands showed that cognitive factors and direct interactions were more important in shaping people’s perception of coexistence than affective factors. Cognitive factors refer to a variety of perceptual factors (e.g. perceived risk of conflict, perceived bear population growth), including values and attitudes (Bruskotter et al. 2009), while affective factors include fear or worry about bears and conflicts (Sjöberg 1998). Similarly to other regions (Lescureux et al. 2011), people’s perceptions about bears were mediated through direct interactions with bears. The importance of direct interactions was shown in themes such as ‘bear behaviour’ in the landscape–bear strand (Table 1, row c). Here, it was emphasized through reduced tolerance of people who had experienced livestock predation, while people who had positive interactions typically also had a positive perception of coexistence. Nevertheless, perceived risk of human–bear conflicts influenced people’s perception of coexistence more strongly than actual negative experiences, which has also been observed elsewhere (Kaczensky et al. 2004; Carter et al. 2012).

In contrast, affective factors such as fear or worry about bears and conflict were rarely mentioned during the interviews. This suggests either a lower impact of affective factors or may indicate that the effect of these factors was explored less deeply during the interviews. This finding is important because affective factors may be related to carnivore killing (Inskip et al. 2014), while in contrast, low fear levels may facilitate tolerance (Roskaft et al. 2003). Given the importance of affective factors elsewhere, we believe it may be worthwhile to further investigate these in our study region in the future.

The landscape–human coexistence strand also showed that key social drivers of people’s perceptions of human–bear coexistence were landscape-mediated attitudes and non-use values (cultural, existence, historical), which were constructed through the existence of active, deep links between people and nature. These deep links are demonstrated through narratives on long-term and evolving attachments to nature (see results section). These values may be more important drivers of people’s perceptions towards carnivores than perceived damage risks (Lagendijk and Gusset 2008; Glikman et al. 2012; Dickman et al. 2014). Moreover, in intact social–ecological systems, cultural tolerance to carnivores is not uncommon (Lagendijk and Gusset 2008), which can reduce carnivore extinction risk (Karanth et al. 2010). Coexistence with carnivores over long periods of time thus may be facilitated through maintaining genuine links to nature, thereby shaping the emotional component of human culture to accept and adapt to human–bear coexistence (Glikman et al. 2012).

People’s perceptions of environmental issues are partly shaped by the degree to which people believe that they are part of the natural environment (Schultz et al. 2004). The landscape–human coexistence strand emphasizes the role of the surrounding landscape, which serves as an interface for people to experience the natural environment and its associated values. Similarly, the landscape–bear strand supports the role of the surrounding landscape as an interface. For example, the land use change theme (Table 1, row b) demonstrates how changes to the landscape influence coexistence. The landscape thus provides a sense of place as well as a daily arena for interaction, connection, and proximity. How factors such as sense of place affect human–carnivore coexistence could be an important domain for further research (Williams and Stewart 1998).

Finally, the management coexistence strand underlined the perceived gaps in current management and showed that perceptions of (mis-)management could become a major obstacle to coexistence. Consistent with the varying responses to management in the questionnaire (Appendix S3), strong negative opinions about current management did not necessarily lead to a negative perception of coexistence. For example, Table 2 rows h to m outline a range of themes raised by those who were dissatisfied with current bear management. However, these respondents did not necessarily go on to have a negative perception of coexistence. Nevertheless, people’s negative opinions on various aspects of current bear management and the feeling of being treated unfairly have the potential to erode the built-up tolerance towards bears. For example, a perceived inadequate governance or a lack of support from the authorities can compel people to retaliatory killing (Treves et al. 2002; Inskip et al. 2014)—poaching in Greece has been shown to be partly motivated by a desire to defy the authorities (Bell et al. 2007). Investigating the management strand proved particularly useful to detect where people perceived mitigation as necessary, which strategies were culturally accepted, and whether current efforts were satisfactory. For example, concerns were raised around an increasing bear population and its control (Table 2, row k), rumours about “secret” carnivore introductions, and inequality over benefits and disadvantages (Table 2, row i). These should be cleared up with a high priority because they could reduce people’s tolerance towards bears (Skogen et al. 2008).

Managing coexistence in Southern Transylvania

The coexistence strands identified in our research are of direct practical use for informing and directing appropriate management interventions in Transylvania. Each strand signals both threats and opportunities for the maintenance of human–carnivore coexistence. For example, the management coexistence strand showed that disagreements between management bodies and local people may hinder coexistence, but management interventions could avoid such disagreements through better citizen participation. Similarly, distrust and the feeling of disempowerment are potential threats to coexistence. However, these can be reduced by more actively including people in carnivore management (Treves et al. 2006), and by developing more effective conflict mitigation strategies (Can et al. 2014). Although none of the interviewed respondents expressed the wish to be directly involved in bear management, several respondents to the questionnaires showed this aspiration (Appendix S3). Co-management with local people could further increase or maintain tolerance through creating shared responsibilities and facilitating improved relationships between authorities and local people (Treves et al. 2006; Lagendijk and Gusset 2008).

Improved citizen participation could also have educational value. Education is a frequently recommended management tool to reduce human–wildlife conflicts (e.g. Treves and Karanth 2003; Spencer et al. 2007). Within the human–landscape coexistence strand, education comes second to experience as the most important way to acquire knowledge about bears. Coexistence strands support education as a coexistence management tool by revealing those specific opportunities and challenges that educational programmes might focus on to increase tolerance towards bears. For example, by looking through the landscape–bear lens, targeting beliefs, such as the difference between ant-eating bears and carnivorous bears, could foster more positive representations of bears through which people may feel less threatened (Zinn et al. 2000).

Finally, direct actions within the management coexistence strand such as well-regulated options for local people to react against certain “carnivorous” problem animals through lethal control could help to increase citizen participation and empower local people (Lescureux and Linnell 2010; Majic et al. 2011). At the same time, non-lethal interventions are often more effective in reducing livestock predation (Bergstrom et al. 2014), and socially accepted methods like diversionary feeding need more attention. Within the management coexistence strand, the anger around compensation schemes may be harder to resolve when they are governed by perceived “weak” institutions (Ferraro and Kiss 2002) that favour an unfair distribution of payments (Hemson et al. 2009). In our study region, the management coexistence strand revealed that the disempowerment perceived by locals and the adversity towards management bodies may fall upon bears and erode the rural population’s tolerance. Hence, although compensation payments or other financial benefits can aid conservation (Dickman et al. 2011), they often do not improve tolerance (Naughton-Treves et al. 2003; Hazzah et al. 2009). Therefore, it could be worthwhile to explore other alternatives to manage human–carnivore conflicts such as bottom-up community organized payments, for example, contributions to a local livestock insurance programme (Mishra et al. 2003).

Coexistence strands as a heuristic for understanding human–wildlife coexistence

Our case study showed how coexistence strands can provide detailed information of factors mediating human–carnivore coexistence, and provided insights into potential intervention points for improved carnivore management. More broadly, the concept of coexistence strands could help to better understand human–wildlife coexistence.

Coexistence strands are grounded in local realities, and thus could be a potentially powerful heuristic for deconstructing the complexity of human–carnivore coexistence. Furthermore, they are compatible with the concept of “social-ecological systems” because they emphasize the integration of humans in nature (Folke 2006). Both approaches recognise interactions among social and biophysical system components, and thus stimulate interdisciplinary integration. For example, the landscape–human coexistence strand presents coexistence as an outcome of internal co-evolutionary processes that enabled locals to experience nature through time.

The elicitation of coexistence strands should be seen as a complementary approach to other, more quantitative approaches seeking to shed light on human–carnivore coexistence (e.g. Appendix S3; Ericsson and Heberlein 2003; Kaczensky et al. 2004; Carter et al. 2012; Kansky et al. 2014). Notably, coexistence strands rely on four components that are common to all places with human–wildlife tensions: a wildlife component, a human component, a physical space where the interaction takes place, and the management of wildlife. Thus, the elicitation of coexistence strands can lay the ground for future analysis by directing social–ecological research towards these four areas.

Conclusion

Facilitating human–carnivore coexistence is a conservation goal worldwide. Our conceptual framework provides ways to approach the complexity of coexistence, by collating social factors under three coexistence strands. We believe this conceptualisation may facilitate improved management of carnivore coexistence by identifying specific factors that facilitate or hinder coexistence, so that interventions can be targeted accordingly. For Southern Transylvania, we advocate for a more participatory approach to carnivore management. This approach should foster people’s connection to their landscape, and provide transparency around management interventions. More broadly, we believe that the general concept of coexistence strands could be extended to regions worldwide. Whereas the deconstruction of coexistence may result in similar strands in many regions, the identification of the social factors populating each strand may differ between regions. Such an extension would allow us to understand whether the specific factors acting under each strand and their outcomes are transferable to other regions and species. Thus, future research on human–carnivore coexistence could empirically populate coexistence strands for different regions and species in order to better understand how social–ecological factors shape human–carnivore coexistence.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hans Hedrich for conducting and translating all the interviews and we thank all respondents for their participation. The survey procedure was cleared by the ethics committee of Leuphana University Lueneburg. The project was funded by a grant of the International Association for Bear Research and Management to ID and a Sofja Kovalevskaja Award by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation to JF.

Biographies

Ine Dorresteijn

is a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Sustainability, Leuphana University Lüneburg. Her research interests include biodiversity conservation in rural landscapes with particular interest into human–wildlife interactions.

Andra Ioana Milcu

is a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Sustainability, Leuphana University Lüneburg. Her research interests include the nature–human connection in rural landscapes.

Julia Leventon

is a Senior Research Associate at the Faculty of Sustainability, Leuphana University Lüneburg. Her research interests include natural resource governance and sustainable development.

Jan Hanspach

is a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Sustainability, Leuphana University Lüneburg. Originally trained as an ecologist, he now works more broadly on human–environment interactions in agricultural landscapes.

Joern Fischer

is a Professor at the Faculty of Sustainability, Leuphana University Lüneburg. His primary interest is the sustainable development of social–ecological systems, with a particular focus on rural areas.

References

- Barua M, Bhagwat SA, Jadhav S. The hidden dimensions of human–wildlife conflict: Health impacts, opportunity and transaction costs. Biological Conservation. 2013;157:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S, Hampshire K, Topalidou S. The political culture of poaching: A case study from northern Greece. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2007;16:399–418. doi: 10.1007/s10531-005-3371-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom BJ, Arias LC, Davidson AD, Ferguson AW, Randa LA, Sheffield SR. License to kill: Reforming federal wildlife control to restore biodiversity and ecosystem function. Conservation Letters. 2014;7:131–142. doi: 10.1111/conl.12045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bixler RP. The political ecology of local environmental narratives: Power, knowledge, and mountain caribou conservation. J. Polit. Ecol. 2013;20:273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Boitani L. Ecological and cultural diversities in the evolution of wolf-human relationships. In: Carbyn LN, Seip DR, editors. Ecology and conservation of wolves in a changing world. Alberta: Canada, Canadian Circumpolar Institute; 1995. pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bruskotter JT, Vaske JJ, Schmidt RH. Social and cognitive correlates of Utah residents’ acceptance of the lethal control of wolves. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 2009;14:119–132. doi: 10.1080/10871200802712571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Can ÖE, D’cruze N, Garshelis DL, Beecham J, Macdonald DW. Resolving human-bear conflict: A global survey of countries, experts and key factors. Conservation Letters. 2014;7:501–513. doi: 10.1111/conl.12117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter NH, Riley SJ, Liu J. Utility of a psychological framework for carnivore conservation. Oryx. 2012;46:525–535. doi: 10.1017/S0030605312000245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesura A, De Groot R. Critical natural capital: A socio-cultural perspective. Ecological Economics. 2003;44:219–231. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00275-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciucci P, Boitani L. The Apennine brown bear: A critical review of its status and conservation problems. Ursus. 2008;19:130–145. doi: 10.2192/07PER012.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman AJ. Complexities of conflict: The importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human-wildlife conflict. Animal Conservation. 2010;13:458–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00368.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman AJ, Hazzah L, Carbone C, Durant SM. Carnivores, culture and ‘contagious conflict’: Multiple factors influence perceived problems with carnivores in Tanzania’s Ruaha landscape. Biological Conservation. 2014;178:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman AJ, Macdonald EA, Macdonald DW. A review of financial instruments to pay for predator conservation and encourage human-carnivore coexistence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:13937–13944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012972108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorresteijn I, Hanspach J, Kecskés A, Latková H, Mezey Z, Sugár S, Von Wehrden H, Fischer J. Human-carnivore coexistence in a traditional rural landscape. Landscape Ecology. 2014;29:1145–1155. doi: 10.1007/s10980-014-0048-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enserink M, Vogel G. Wildlife conservation—The carnivore comeback. Science. 2006;314:746–749. doi: 10.1126/science.314.5800.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson G, Heberlein TA. Attitudes of hunters, locals, and the general public in Sweden now that the wolves are back. Biological Conservation. 2003;111:149–159. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00258-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro PJ, Kiss A. Direct payments to conserve biodiversity. Science. 2002;298:1718–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1078104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folke C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change. 2006;16:253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glikman JA, Vaske JJ, Bath AJ, Ciucci P, Boitani L. Residents’ support for wolf and bear conservation: The moderating influence of knowledge. European Journal of Wildlife Research. 2012;58:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s10344-011-0579-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray T, Hatchard J, Daw T, Stead S. New cod war of words: ‘Cod is God’versus ‘sod the cod’—Two opposed discourses on the North Sea Cod Recovery Programme. Fisheries Research. 2008;93:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2008.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gusset M, Maddock AH, Gunther GJ, Szykman M, Slotow R, Walters M, Somers MJ. Conflicting human interests over the re-introduction of endangered wild dogs in South Africa. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2008;17:83–101. doi: 10.1007/s10531-007-9232-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazzah L, Borgerhoff Mulder M, Frank L. Lions and Warriors: Social factors underlying declining African lion populations and the effect of incentive-based management in Kenya. Biological Conservation. 2009;142:2428–2437. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemson G, Maclennan S, Mills G, Johnson P, Macdonald D. Community, lions, livestock and money: A spatial and social analysis of attitudes to wildlife and the conservation value of tourism in a human–carnivore conflict in Botswana. Biological Conservation. 2009;142:2718–2725. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmern T, Nyahongo J, Røskaft E. Livestock loss caused by predators outside the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Biological Conservation. 2007;135:518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.10.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington HP. Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: Methods and applications. Ecological Applications. 2000;10:1270–1274. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1270:UTEKIS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inskip C, Fahad Z, Tully R, Roberts T, Macmillan D. Understanding carnivore killing behaviour: Exploring the motivations for tiger killing in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh. Biological Conservation. 2014;180:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczensky P, Blazic M, Gossow H. Public attitudes towards brown bears (Ursus arctos) in Slovenia. Biological Conservation. 2004;118:661–674. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2003.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczensky P, Jerina K, Jonozovič M, Krofel M, Skrbinšek T, Rauer G, Kos I, Gutleb B. Illegal killings may hamper brown bear recovery in the Eastern Alps. Ursus. 2011;22:37–46. doi: 10.2192/URSUS-D-10-00009.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kansky R, Kidd M, Knight AT. Meta-analysis of attitudes toward damage-causing mammalian wildlife. Conservation Biology. 2014;28:924–938. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanth KK, Nichols JD, Karanth KU, Hines JE, Christensen NL. The shrinking ark: Patterns of large mammal extinctions in India. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277:1971–1979. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagendijk DG, Gusset M. Human–carnivore coexistence on communal land bordering the Greater Kruger Area, South Africa. Environmental Management. 2008;42:971–976. doi: 10.1007/s00267-008-9204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescureux N, Linnell J, Mustafa S, Melovski D, Stojanov A, Ivanov G, Avukatov V. The king of the forest: Local knowledge about European brown bears (Ursus arctos) and implications for their conservation in contemporary Western Macedonia. Conservation and Society. 2011;9:189. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.86990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lescureux N, Linnell JD. Knowledge and perceptions of Macedonian hunters and herders: The influence of species specific ecology of bears, wolves, and lynx. Human Ecology. 2010;38:389–399. doi: 10.1007/s10745-010-9326-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer DB, Fischer J. Habitat fragmentation and landscape change: An ecological and conservation synthesis. Washington DC: Island Press; 2006. p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Madden F, Mcquinn B. Conservation’s blind spot: The case for conflict transformation in wildlife conservation. Biological Conservation. 2014;178:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majić A, de Bodonia AMT, Huber Đ, Bunnefeld N. Dynamics of public attitudes toward bears and the role of bear hunting in Croatia. Biological Conservation. 2011;144:3018–3027. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson DJ, Clark SG. The discourses of incidents: Cougars on Mt. Elden and in Sabino Canyon, Arizona. Policy Sciences. 2012;45:315–343. doi: 10.1007/s11077-012-9158-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra C, Allen P, Mccarthy T, Madhusudan M, Bayarjargal A, Prins HH. The role of incentive programs in conserving the snow leopard. Conservation Biology. 2003;17:1512–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00092.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton-Treves L, Grossberg R, Treves A. Paying for tolerance: rural citizens’ attitudes toward wolf depredation and compensation. Conservation Biology. 2003;17:1500–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00060.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MG. From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal. 2009;52:856–862. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2009.44632557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Redpath SM, Young J, Evely A, Adams WM, Sutherland WJ, Whitehouse A, Amar A, Lambert RA, et al. Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2012;28:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripple WJ, Estes JA, Beschta RL, Wilmers CC, Ritchie EG, Hebblewhite M, Berger J, Elmhagen B, et al. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science. 2014;343:1241484. doi: 10.1126/science.1241484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskaft E, Bjerke T, Kaltenborn B, Linnell JDC, Andersen R. Patterns of self-reported fear towards large carnivores among the Norwegian public. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2003;24:184–198. doi: 10.1016/S1090-5138(03)00011-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz PW, Shriver C, Tabanico JJ, Khazian AM. Implicit connections with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2004;24:31–42. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00022-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg L. Worry and risk perception. Risk Analysis. 1998;18:85–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skogen K, Mauz I, Krange O. Cry wolf!: Narratives of wolf recovery in france and norway. Rural Sociology. 2008;73:105–133. doi: 10.1526/003601108783575916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RD, Beausoleil RA, Martorello DA. How agencies respond to human-black bear conflicts: A survey of wildlife agencies in North America. Ursus. 2007;18:217–229. doi: 10.2192/1537-6176(2007)18[217:HARTHB]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thirgood S, Woodroffe R, Rabinowitz A. The impact of human-wildlife conflict on human lives and livelihoods. In: Woodroffe R, Thirgood S, Rabinowitz A, editors. People and wildlife, conflict or co-existence? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Treves A, Jurewicz RR, Naughton-Treves L, Rose RA, Willging RC, Wydeven AP. Wolf depredation on domestic animals in Wisconsin, 1976–2000. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 2002;30:231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Treves A, Karanth KU. Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conservation Biology. 2003;17:1491–1499. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00059.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treves A, Wallace RB, Naughton-Treves L, Morales A. Co-managing human–wildlife conflicts: A review. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 2006;11:383–396. doi: 10.1080/10871200600984265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Stewart SI. Sense of place: An elusive concept that is finding a home in ecosystem management. Journal of Forestry. 1998;96:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Woodroffe R. Predators and people: Using human densities to interpret declines of large carnivores. Animal Conservation. 2000;3:165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2000.tb00241.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zedrosser A, Dahle B, Swenson JE, Gerstl N. Status and management of the brown bear in Europe. Ursus. 2001;12:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zinn HC, Manfredo MJ, Vaske JJ. Social psychological bases for Stakeholder acceptance Capacity. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 2000;5:20–33. doi: 10.1080/10871200009359185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.