Abstract

Rationale: The use of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) for acute respiratory failure in children is prevalent despite the lack of efficacy data.

Objectives: To compare the outcomes of patients with acute respiratory failure managed with HFOV within 24–48 hours of endotracheal intubation with those receiving conventional mechanical ventilation (CMV) and/or late HFOV.

Methods: This is a secondary analysis of data from the RESTORE (Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure) study, a prospective cluster randomized clinical trial conducted between 2009 and 2013 in 31 U.S. pediatric intensive care units. Propensity score analysis, including degree of hypoxia in the model, compared the duration of mechanical ventilation and mortality of patients treated with early HFOV matched with those treated with CMV/late HFOV.

Measurements and Main Results: Among 2,449 subjects enrolled in RESTORE, 353 patients (14%) were ever supported on HFOV, of which 210 (59%) had HFOV initiated within 24–48 hours of intubation. The propensity score model predicting the probability of receiving early HFOV included 1,064 patients (181 early HFOV vs. 883 CMV/late HFOV) with significant hypoxia (oxygenation index ≥8). The degree of hypoxia was the most significant contributor to the propensity score model. After adjusting for risk category, early HFOV use was associated with a longer duration of mechanical ventilation (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.64–0.89; P = 0.001) but not with mortality (odds ratio, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.92–1.79; P = 0.15) compared with CMV/late HFOV.

Conclusions: In adjusted models including important oxygenation variables, early HFOV was associated with a longer duration of mechanical ventilation. These analyses make supporting the current approach to HFOV less convincing.

Keywords: high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, mechanical ventilation, pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome, oxygenation index

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Data supporting the use of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) for the management of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome remain elusive in the era of low tidal volume conventional ventilation.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study provides evidence of worse outcomes, as shown by clinically significant longer days of mechanical ventilation, for patients treated with early HFOV as compared with patients treated with conventional mechanical ventilation or late HFOV. The study design and scope of data collection in this analysis has allowed the results to be highly generalizable and vital for guiding future studies aimed at decreasing the burden of acute respiratory failure in critically ill children.

For more than 20 years, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) has been a staple in the management of children with acute respiratory failure (1, 2). HFOV is a mode of mechanical ventilation that recruits diseased lung and improves oxygenation through the use of high mean airway pressures (MAPs) with tidal volumes less than anatomic dead space. Although HFOV is commonly used in children, efficacy data are limited (3, 4) and predate the era of low tidal volume conventional mechanical ventilation (CMV) (5).

Recently, two large randomized controlled trials in adult patients tested the efficacy of HFOV in moderate to severe respiratory failure and reported negative results. OSCILLATE (High-Frequency Oscillation in Early Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome) study stopped early because of increased mortality in the HFOV-managed group (6), and OSCAR (High-Frequency Oscillation for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome) study reported no difference in all-cause mortality between patients managed with HFOV and patients managed with CMV (7). In neonates, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials concluded that the use of early HFOV, within 24–48 hours of admission, was at least as effective as CMV (8). In the absence of comparable pediatric trials, data from the virtual pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) were recently used to compare outcomes in patients supported on HFOV or CMV (9). Propensity scoring was used to match the two groups on severity of illness and admission diagnoses. Results showed worse clinical outcomes including higher mortality, longer hospital days, and more ventilator days in the HFOV group. However, these data have been criticized because matching patients by degree of hypoxia or ventilator parameters, important clinical components of HFOV, was not available in virtual PICU (10–12).

Completion of the RESTORE (Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure) study provides an opportunity to use data, collected prospectively within a clinical trial, to further probe the pediatric HFOV question (13). Daily data include ventilator mode, MAP, and degree of hypoxia. Here we use these data to compare the length of mechanical ventilation and mortality in patients managed early with HFOV with those receiving CMV using a propensity score analysis.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of data from the RESTORE study, a prospective cluster randomized clinical trial conducted between 2009 and 2013 in 31 U.S. PICUs (13). The primary aim of RESTORE was to determine whether critically ill children managed with a nurse-implemented, goal-directed sedation protocol experience fewer days of mechanical ventilation than patients receiving usual care. In brief, PICUs were randomized to either usual care or a protocol that included targeted sedation, arousal assessments, extubation readiness testing, sedation adjustment every 8 hours, and sedation weaning.

All enrolled patients were aged 2 weeks to 17 years and received invasive mechanical ventilation for acute airways disease and/or parenchymal lung disease. Patients expected to be extubated within 24 hours were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardian of each subject. Other than using the sedation protocol at intervention PICUs, no other aspect of care was prescribed by study protocol. Decisions about mechanical ventilation mode and ventilator weaning strategy were left to the discretion of the treating physician.

HFOV-managed patients include any patients receiving HFOV for any duration of time before successful extubation (off mechanical ventilation for at least 24 h). Because the effects of either HFOV or CMV are thought to depend on the timing of exposure, we compared the use of “early HFOV” versus CMV. Early HFOV was defined as initiation of HFOV on Day 0 (day of endotracheal intubation until midnight the same day) or Day 1 (subsequent 24 h). The CMV group included those patients with HFOV initiated after Day 1 and thus was entitled “CMV/late HFOV.” Patients who received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) before or the same day as HFOV were included in the CMV/late HFOV group.

Baseline characteristics included demographic data, Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category and Pediatric Overall Performance Category (14), PRISM (Pediatric Risk of Mortality) III-12 score (15), primary diagnosis resulting in respiratory failure as defined by the treating physician, past medical history, and intervention group (sedation protocol vs. usual care).

Mechanical ventilation mode and MAP were captured. Oxygenation index (OI [FiO2 × MAP]/PaO2 × 100]) for patients who had arterial blood gases and/or oxygenation saturation index (OSI [FiO2 × MAP/oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry × 100]) for patients without an arterial blood gas were calculated based on worst values on the day of intubation/PICU admission and daily values closest to 08:00. Worst OI and OSI was defined as the highest (most hypoxic) of the admission, Day 0, and Day 1 values. Categories of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (PARDS) were based on worst OI or OSI as at risk (OI <4.0 or OSI <5.0), mild (OI = 4.0–7.9 or OSI = 5.0–7.4), moderate (OI = 8.0–15.9 or OSI = 7.5–12.2), or severe (OI ≥16.0 or OSI ≥12.3) (16). Organ dysfunction on Days 0–1 was also calculated (17).

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analysis

Analyses focused on comparing outcomes of patients who received early HFOV versus those with CMV/late HFOV. Primary outcomes were duration of mechanical ventilation through 28 days and in-hospital mortality at 90 days. Patients were assigned 28 days of mechanical ventilation if they remained intubated, were transferred, or died before Day 28 without remaining extubated for 24 hours, therefore making this outcome equivalent to ventilator-free days (18). Secondary outcomes included time to recovery from acute respiratory failure, duration of weaning from mechanical ventilation, ECMO, use of neuromuscular blockade (NMB) and sedatives, Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category and Pediatric Overall Performance Category at hospital discharge, and location at hospital discharge (13).

Patient characteristics were compared across groups using logistic, linear, cumulative logit, or multinomial logistic regression for binary, log-transformed continuous, ordinal, and nominal variables, respectively. Analyses of outcome data used these methods and proportional hazards regression for length of time variables. All regression analyses accounted for PICU as a cluster variable using generalized estimating equations (19). Site variability in early HFOV was evaluated by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient from an analysis of variance adjusting for age category and PRISM III-12 score, with confidence intervals (CIs) constructed using Searle’s method to adjust for unequal sample sizes across sites (20, 21). HFOV usage by site ranged from 2 to 35% of enrolled patients with a cluster of five sites using HFOV on greater than 25% of enrolled patients, possibly indicating a greater familiarity of HFOV usage. We defined these sites as high HFOV usage sites.

To estimate the effects of early HFOV versus CMV/late HFOV on outcomes, two propensity score matching methods were used to account for covariates that predict receiving early HFOV (22). Adjusting for age category and PRISM III-12 score, we used stepwise multivariable logistic regression to generate models to estimate the probability of receiving early HFOV. The primary analysis (model 1) was restricted to patients with a worst OI greater than or equal to 8.0 on Days 0–1 and considered worst OI as a potential categorical covariate (8.0–15.9, 16.0–24.9, 25.0–39.9, ≥40.0). A secondary analysis (model 2) used all patients and considered PARDS (mild or at risk, moderate, severe) as a potential covariate. Other potential covariates included variables with P less than 0.2 in univariate analyses except primary diagnosis.

In each analysis, the fitted probabilities (propensity scores) from the model were used to stratify patients into quintiles. First, we assessed the effects of early HFOV versus CMV/late HFOV on outcomes adjusting for risk category based on these quintiles. Second, we assessed the effects of early HFOV versus CMV/late HFOV on outcomes in analyses stratified by quintiles. Because of the small numbers of patients who received HFOV in the lowest three quintiles and hence a lack of power, a decision was made to concentrate our analyses on quintiles 4 and 5. The duration of mechanical ventilation was also evaluated using Kaplan-Meier curves. All data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Among the 2,449 subjects enrolled in RESTORE, 353 (14%) were ever supported on HFOV, with all 31 sites having at least one patient on HFOV. Of these, nine patients received ECMO before or the same day as HFOV. Fifty-nine percent (n = 210) of all HFOV use was early HFOV. The site variability of early HFOV use ranged from 0 to 28% of RESTORE patients with a median of 8% (interquartile range [IQR], 4–14%). The intraclass correlation coefficient for early HFOV use was 0.066 (95% CI, 0.040–0.117), indicating moderately strong variation in the use of early HFOV across sites. Early HFOV-treated patients used HFOV for a median of 108 hours (IQR, 51–196; range, 0.2–687). In the CMV/late HFOV group, 134 (6%) received late HFOV.

Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of the early HFOV and CMV/late HFOV groups. Early HFOV-treated patients were older and had higher PRISM III-12 scores. A higher proportion of early HFOV patients had admitting diagnoses of pneumonia and sepsis, whereas a higher proportion of CMV/late HFOV patients had bronchiolitis or asthma diagnoses. More early HFOV patients had a current or past diagnosis of cancer and organ dysfunctions on Days 0–1. There was no difference in the use of early HFOV in patients in the intervention versus control sites.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics According to Group

| Characteristics | Early HFOV (n = 210) | CMV/Late HFOV (n = 2,239) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at PICU admission | |||

| Median (IQR), yr | 3.6 (1.0–10.3) | 1.7 (0.4–8.0) | 0.002 |

| Number (%) | 0.002 | ||

| 6.00–17.99 yr | 85 (40) | 681 (30) | |

| 2.00–5.99 yr | 43 (20) | 375 (17) | |

| 2 wk–1.99 yr | 82 (39) | 1,183 (53) | |

| Female, n (%) | 104 (50) | 997 (45) | 0.16 |

| Non-Hispanic white, n/total (%) | 104/206 (50) | 1,129/2,219 (51) | 0.61 |

| Cognitive impairment (baseline PCPC score >1), n (%)† | 53 (25) | 531 (24) | 0.95 |

| Functional impairment (baseline POPC score >1), n (%)† | 65 (31) | 637 (28) | 0.92 |

| PRISM III-12 score, median (IQR) | 11.5 (5–20) | 7 (3–12) | <0.001 |

| Percent risk of mortality based on PRISM III-12 score, median (IQR), % | 11.7 (2.6–40.7) | 3.4 (1.0–11.6) | <0.001 |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Pneumonia | 83 (40) | 744 (33) | |

| Bronchiolitis | 29 (14) | 627 (28) | |

| Acute respiratory failure r/t sepsis | 47 (22) | 310 (14) | |

| Asthma or reactive airway disease | 4 (2) | 203 (9) | |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 9 (4) | 140 (6) | |

| Other‡ | 38 (18) | 215 (10) | |

| Past medical history, n (%) | |||

| Any past medical history§ | 112 (53) | 1,075 (48) | 0.21 |

| Prematurity (<36 wk postmenstrual age) | 27 (13) | 342 (15) | 0.39 |

| Asthma (prescribed bronchodilators or steroids) | 24 (11) | 332 (15) | 0.28 |

| Seizure disorder (prescribed anticonvulsants) | 20 (10) | 204 (9) | 1.0 |

| Neurologic/neuromuscular disorder putting patient at risk of aspiration | 16 (8) | 185 (8) | 0.59 |

| Cancer (current or previous diagnosis) | 35 (17) | 162 (7) | <0.001 |

| Known chromosomal abnormality | 10 (5) | 98 (4) | 0.79 |

| Intervention group, n (%) | 108 (51) | 1,117 (50) | 0.31 |

| Worst OI on Days 0–1, median (IQR)|| | 28.2 (19.5–43.5) | 10.2 (5.9–17.1) | <0.001 |

| Worst OSI on Days 0–1, median (IQR)|| | 22.4 (13.5–39.2) | 6.7 (3.9–12.0) | <0.001 |

| PARDS based on worst OI or OSI on Days 0–1, n (%)|| | <0.001¶ | ||

| At risk (OI <4.0 or OSI <5.0) | 0 | 377 (17) | |

| Mild (OI 4.0–7.9 or OSI 5.0–7.4) | 3 (1) | 530 (24) | |

| Moderate (OI 8.0–15.9 or OSI 7.5–12.2) | 26 (12) | 670 (30) | |

| Severe (OI ≥16.0 or OSI ≥12.3) | 181 (86) | 662 (30) | |

| Organ dysfunction on Days 0–1** | |||

| Median (IQR), number of organ dysfunctions | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–3) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular | 163 (78) | 763 (34) | <0.001 |

| Neurologic | 115 (55) | 782 (35) | <0.001 |

| Hematologic | 59 (28) | 300 (13) | <0.001 |

| Renal | 18 (9) | 96 (4) | 0.02 |

| Hepatic | 58 (28) | 275 (12) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: CMV = conventional mechanical ventilation; HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; IQR = interquartile range; OI = oxygenation index; OSI = oxygen saturation index; PARDS = pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome; PCPC = Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category; PICU = pediatric intensive care unit; POPC = Pediatric Overall Performance Category; PRISM III-12 = Pediatric Risk of Mortality III score from first 12 hours in the PICU; r/t = related to.

P values for the comparison between groups were calculated using linear, cumulative logit, logistic, and multinomial logistic regression accounting for PICU as a cluster variable using generalized estimating equations for log-transformed continuous, ordinal, binary, and nominal variables, respectively.

PCPC and POPC scores range from 1 to 6, with higher categories indicating greater impairment.

Other primary diagnoses include pulmonary edema, thoracic trauma, pulmonary hemorrhage, laryngotracheobronchitis, acute respiratory failure after bone marrow transplantation, acute chest syndrome/sickle cell disease, pertussis, pneumothorax (nontrauma), acute exacerbation lung disease (cystic fibrosis or bronchopulmonary dysplasia), acute respiratory failure related to multiple blood transfusions, pulmonary hypertension (not primary), and other.

Any past medical history includes prematurity, asthma, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cystic fibrosis, insulin-dependent diabetes, immunodeficiency, neurologic/neuromuscular disorder that places patient at risk for aspiration, seizure disorder, cancer, sickle cell disease, nonoperative cardiovascular disease, and chromosomal abnormality.

Oxygenation index was calculated as ([FiO2 × mean airway pressure]/PaO2 × 100). When an arterial blood gas measurement was not available, SpO2 was used to estimate PaO2 to calculate OSI ([FiO2 × mean airway pressure]/SpO2 × 100). Lower scores reflect better oxygenation. Worst OI calculated for 195 early HFOV and 1,402 CMV/late HFOV patients. Worst OSI calculated for 60 early HFOV and 1,326 CMV/late HFOV patients.

Mild and at risk collapsed into one category for calculation of P value.

All patients had respiratory dysfunction. Cardiovascular dysfunction based on vasoactive medication use (single or multiple). Neurologic dysfunction based on worst level of consciousness (stupor or coma) or pupillary response (one or both pupils nonreactive). Hematologic dysfunction based on platelet threshold (<80 K/μl). Renal dysfunction based on age-specific creatinine thresholds. Hepatic dysfunction based on age- and sex-specific alanine aminotransferase thresholds or total bilirubin thresholds.

Most early HFOV-treated patients had moderate (n = 26, 12%) or severe PARDS (n = 181, 86%). Most early HFOV patients (n = 195; 93%) had arterial blood samples and of these, 192 (98%) had an OI greater than or equal to 8.0, and 118 (61%) had an OI greater than or equal to 25.0. The CMV/late HFOV-treated patients included 670 (30%) with moderate and 662 (30%) with severe PARDS. Arterial blood samples were available in 1,402 (63%) of CMV/late HFOV patients, and of these 872 (62%) had an OI greater than or equal to 8.0, and 167 (12%) had an OI greater than or equal to 25.0. As hypoxia worsened, the percentage of patients treated with early HFOV increased (see Figure E1 in the online supplement).

In the primary propensity score analysis of the 1,064 patients with an OI greater than or equal to 8.0, the regression model (model 1) to predict the probability of receiving early HFOV identified multiple risk factors (Table 2). The most significant contributor to the model was degree of hypoxia. Compared with an OI of 8.0–15.9, the odds ratio of receiving early HFOV increased with degree of hypoxia, from 2.52 (95% CI, 1.86–3.40) for an OI of 16.0–24.9, to 5.76 (95% CI, 3.61–9.18) for an OI of 25.0–39.9, and to 17.21 (95% CI, 10.03–29.52) for an OI greater than or equal to 40. The odds of receiving early HFOV also significantly increased with cardiovascular and neurologic dysfunction on Days 0–1, as well as younger age. Using these factors, the patients were matched by propensity scoring into quintiles of risk. Table 3 and Table E1 compare the characteristics of patients by quintile (the two quintiles of lowest risk were combined because of small numbers of patients receiving early HFOV) demonstrating distinctive pattern differences by quintile.

Table 2.

Multivariable Model 1 to Predict Early HFOV in 1,064 Patients with Worst OI ≥8.0 on Days 0–1

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI)* | P Value† |

|---|---|---|

| Age at PICU admission | 0.01 | |

| 6.00–17.99 yr | 1.00 | |

| 2.00–5.99 yr | 1.23 (0.81–1.85) | |

| 2 wk–1.99 yr | 1.66 (1.16–2.36) | |

| PRISM III-12 score (one-point increase) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.58 |

| Worst OI on Days 0–1 | <0.001 | |

| 8.0–15.9 | 1.00 | |

| 16.0–24.9 | 2.52 (1.86–3.40) | |

| 25.0–39.9 | 5.76 (3.61–9.18) | |

| ≥40.0 | 17.21 (10.03–29.52) | |

| Cardiovascular dysfunction on Days 0–1 | 2.31 (1.64–3.24) | <0.001 |

| Neurologic dysfunction on Days 0–1 | 1.50 (1.05–2.14) | 0.03 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; OI = oxygenation index; PICU = pediatric intensive care unit; PRISM III-12 = Pediatric Risk of Mortality III score from first 12 hours in the PICU.

Odds ratio >1 indicates higher risk of early HFOV.

P values were calculated using logistic regression accounting for PICU as a cluster variable using generalized estimating equations.

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics According to Model 1 Propensity Score Quintile

| Characteristics | Quintile 5 (Highest Risk of Early HFOV) (n = 213) | Quintile 4 (n = 213) | Quintile 3 (n = 213) | Quintiles 1-2 (Lowest Risk of Early HFOV) (n = 425) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early HFOV, n (%) | 99 (46) | 50 (23) | 26 (12) | 17 (4) | <0.001 |

| Age at PICU admission | |||||

| Median (IQR), yr | 4.3 (1.2–11.5) | 6.7 (2.4–13.1) | 3.3 (0.5–10.8) | 4.0 (1.0–9.8) | 0.07 |

| No. (%) | 0.18 | ||||

| 6.00–17.99 yr | 87 (41) | 113 (53) | 84 (39) | 173 (41) | |

| 2.00–5.99 yr | 49 (23) | 52 (24) | 31 (15) | 100 (24) | |

| 2 wk–1.99 yr | 77 (36) | 48 (23) | 98 (46) | 152 (36) | |

| PRISM III-12 score, median (IQR) | 15 (9–22) | 12 (6–19) | 10 (5–14) | 7 (3–11) | <0.001 |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Pneumonia | 72 (34) | 95 (45) | 82 (39) | 156 (37) | |

| Bronchiolitis | 18 (8) | 18 (8) | 32 (15) | 81 (19) | |

| Acute respiratory failure r/t sepsis | 75 (35) | 42 (20) | 47 (22) | 55 (13) | |

| Asthma or reactive airway disease | 6 (3) | 13 (6) | 20 (9) | 57 (13) | |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 10 (5) | 12 (6) | 15 (7) | 24 (6) | |

| Other | 32 (15) | 33 (15) | 17 (8) | 52 (12) | |

| Any past medical history, n (%) | 106 (50) | 118 (55) | 110 (52) | 246 (58) | 0.07 |

| Organ dysfunction on Days 0–1 | |||||

| Median (IQR), number of organ dysfunctions | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (1–2) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) | |||||

| Cardiovascular | 184 (86) | 162 (76) | 146 (69) | 111 (26) | <0.001 |

| Neurologic | 136 (64) | 110 (52) | 104 (49) | 118 (28) | <0.001 |

| Hematologic | 68 (32) | 56 (26) | 41 (19) | 61 (14) | <0.001 |

| Renal | 16 (8) | 22 (10) | 13 (6) | 14 (3) | 0.002 |

| Hepatic | 63 (30) | 52 (24) | 40 (19) | 52 (12) | <0.001 |

| Worst OI on Days 0–1, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| 8.0–15.9 | 0 | 5 (2) | 116 (54) | 380 (89) | |

| 16.0–24.9 | 14 (7) | 134 (63) | 85 (40) | 45 (11) | |

| 25.0–39.9 | 100 (47) | 74 (35) | 12 (6) | 0 | |

| ≥40.0 | 99 (46) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Definition of abbreviations: HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; IQR = interquartile range; OI = oxygenation index; PICU = pediatric intensive care unit; PRISM III-12 = Pediatric Risk of Mortality III score from first 12 hours in the PICU; r/t = related to.

P values for the comparison between groups were calculated using logistic, linear, cumulative logit, and multinomial logistic regression accounting for PICU as a cluster variable using generalized estimating equations for binary, log-transformed continuous, ordinal, and nominal variables, respectively.

Early HFOV use was associated with a longer duration of mechanical ventilation after adjusting for risk category (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.64–0.89; P = 0.001). However, the use of early HFOV was not significantly associated with mortality after adjusting for risk category (odds ratio, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.92–1.79; P = 0.15).

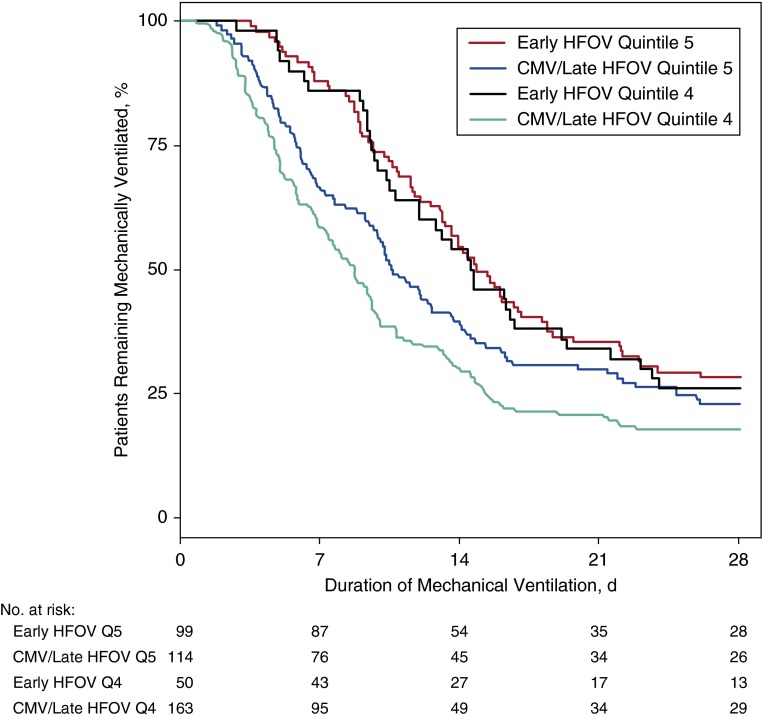

The highest risk category, representing patients with the most hypoxia, included 99 (52%) of the early HFOV patients with an OI greater than or equal to 8.0 and 114 (13%) of the CMV/late HFOV patients with an OI greater than or equal to 8.0. In this quintile, the worst OI on Days 0–1 was higher for the early HFOV patients (early HFOV, median, 43.2 [IQR, 31.0–58.0] vs. CMV/late HFOV, median, 32.3 [IQR, 27.3–43.5]; P < 0.001). Duration of mechanical ventilation was longer in the early HFOV patients but did not reach statistical significance (median, 14.9 vs. 10.8 d; P = 0.08) (Table 4, Figure 1). Mortality was high in both groups (25% vs. 17%; P = 0.09). In this quintile, 21 (18%) patients in the CMV/late HFOV group went onto HFOV after Day 1.

Table 4.

Outcomes According to Model 1 Propensity Score Quintile and Group

| Outcomes | Quintile 5 (Highest Risk of Early HFOV) |

Quintile 4 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early HFOV (n = 99) | CMV/Late HFOV (n = 114) | P Value* | Early HFOV (n = 50) | CMV/Late HFOV (n = 163) | P Value* | |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, median (IQR), d† | 14.9 (9.7–28.0) | 10.8 (5.8–24.9) | 0.08 | 14.7 (9.6–28.0) | 8.7 (4.8–15.1) | <0.001 |

| Time to recovery from acute respiratory failure, median (IQR), d‡ | 10.0 (6.2–12.9) | 5.6 (3.0–10.8) | 0.04 | 9.8 (7.0–17.9) | 4.0 (2.5–8.0) | <0.001 |

| Duration of weaning from mechanical ventilation, median (IQR), d§ | 2.2 (1.1–4.9) | 2.2 (1.2–5.2) | 0.59 | 3.0 (1.1–4.4) | 2.3 (1.1–4.4) | 0.59 |

| In-hospital mortality at 90 d, n (%) | 25 (25) | 19 (17) | 0.09 | 5 (10) | 20 (12) | 0.49 |

| ECMO, n (%) | 11 (11) | 16 (14) | 0.12 | 6 (12) | 8 (5) | 0.04 |

| Neuromuscular blockade used to facilitate mechanical ventilation, median (IQR), % ventilator days | 53 (33–75) | 25 (0–56) | <0.001 | 52 (25–70) | 20 (0–43) | <0.001 |

| Peak daily opioid dose, median (IQR), mg/kg | 6.3 (3.6–11.1) | 5.1 (3.0–8.2) | 0.03 | 8.7 (5.8–10.9) | 3.8 (2.0–6.4) | <0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment (PCPC >1) at hospital discharge, n (%)|| | 33 (46) | 30 (33) | 0.007 | 16 (39) | 50 (36) | 0.98 |

| Functional impairment (POPC >1) at hospital discharge, n (%)|| | 43 (61) | 42 (46) | 0.048 | 19 (46) | 64 (46) | 0.75 |

| Discharged home by 90 d, n (%)|| | 54 (73) | 78 (82) | 0.16 | 34 (76) | 119 (83) | 0.28 |

Definition of abbreviations: CMV = conventional mechanical ventilation; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; IQR = interquartile range; PCPC = Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category; POPC = Pediatric Overall Performance Category.

Within each quintile, P values for the comparison of outcomes between groups were calculated using proportional hazards, logistic, and linear regression accounting for PICU as a cluster variable using generalized estimating equations for time-to-event, binary, and continuous variables, respectively. Peak daily opioid dose was log-transformed.

Patients were assigned 28 days of mechanical ventilation if they remained intubated or were transferred or died before Day 28 without remaining extubated for 24 h, therefore making the outcome equivalent to ventilator-free days.

Time to recovery from acute respiratory failure was defined as the duration from Day 0 start (endotracheal intubation, initiation of assisted breathing for chronically trached patients, or PICU admission for patients intubated at an outside hospital) to the time that the patient first met criteria to be tested for extubation readiness (spontaneously breathing and oxygenation index ≤6). Excludes nonsurvivors who did not meet criteria before death. For survivors who never met criteria, the duration of recovery was set equal to the duration of mechanical ventilation if the patient was successfully extubated or to 28 days if the patient was still intubated on Day 28 or transferred to another PICU still intubated. Within quintile 5, calculated for 76 early HFOV and 98 CMV/late HFOV patients. Within quintile 4, calculated for 45 early HFOV and 147 CMV/late HFOV patients.

Duration of weaning from mechanical ventilation was defined as the duration from the time that the patient first met criteria to be tested for extubation readiness to successful endotracheal extubation (remained extubated for >24 h) or successful removal of assisted breathing for trached patients. Excludes nonsurvivors who were not extubated for >24 hours before death. Also excludes survivors who never met criteria or were still intubated on Day 28. Within quintile 5, calculated for 63 early HFOV and 82 CMV/late HFOV patients. Within quintile 4, calculated for 34 early HFOV and 122 CMV/late HFOV patients.

PCPC, POPC, and location at hospital discharge exclude nonsurvivors. Within quintile 5, PCPC and POPC at hospital discharge known for 71 early HFOV and 92 CMV/late HFOV survivors. Within quintile 4, known for 41 early HFOV and 140 CMV/late HFOV survivors.

Figure 1.

Duration of mechanical ventilation to Day 28 by model 1 propensity score quintile and group. CMV = conventional mechanical ventilation; HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; Q = quintile.

The second highest risk category included 50 (26%) of the early HFOV patients with an OI greater than or equal to 8.0 and 163 (19%) of the CMV/late HFOV patients with an OI greater than or equal to 8.0. The patients had significant hypoxia in this category, with no difference between early HFOV (median OI, 23.4 [IQR, 19.8–28.2]) and CMV/late HFOV (median OI, 21.7 [IQR, 18.4–27.3]) patients (P = 0.23). Duration of mechanical ventilation was significantly longer in the early HFOV patients (median, 14.7 vs. 8.7 d; P < 0.001), although mortality was similar between groups (10% vs. 12%; P = 0.49). A total of 17 (10%) CMV/late HFOV patients in this quintile went onto HFOV after Day 1.

The multivariable model (model 2) to estimate the probability of receiving early HFOV from the secondary propensity score analysis of all 2,449 patients was similar to that of the primary analysis (see Table E2). The odds of receiving early HFOV increased as the degree of hypoxia, determined by either worst OI or OSI, increased. The odds of receiving early HFOV also significantly increased with cardiovascular and neurologic dysfunction on Days 0–1, younger age, and higher PRISM III-12 score. Tables E3 and E4 compare the characteristics of all patients by quintile. Early HFOV use was significantly associated with a longer duration of mechanical ventilation after adjusting for risk category (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54–0.76; P < 0.001). The use of early HFOV was also significantly associated with mortality after adjusting for risk category (odds ratio, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.23–2.65; P = 0.002). Within the two highest risk categories, early HFOV was significantly associated with both longer duration of mechanical ventilation and higher mortality (see Table E5).

Late HFOV patients (n = 134), when compared with early HFOV patients (n = 210), had significantly longer durations of mechanical ventilation (median, 22.0 vs. 13.6 d; P < 0.001) but similar mortality (19% vs. 18%; P = 0.46) and ECMO rates (12% vs. 9%; P = 0.25) (see Table E6). There were no differences in outcomes between HFOV patients at the five high-HFOV usage sites compared with 26 low HFOV usage sites, but more HFOV patients at highusage sites received early HFOV (see Table E7).

Discussion

Definitive evidence supporting the use of HFOV for the management of PARDS remains elusive in the era of low tidal volume conventional ventilation. This study provides evidence of worse outcomes, as shown by clinically significant longer days of mechanical ventilation, for patients treated with early HFOV as compared with patients treated with CMV or late HFOV. In stratified analyses, early HFOV-treated patients had longer time to recovery from acute respiratory failure, more sedative use, and double NMB use. There were no group differences in 90-day mortality in the primary propensity score analysis, but early HFOV was associated with higher mortality in the secondary analysis.

Although these data support an earlier report of negative outcomes associated with HFOV in children and are consistent with adult HFOV trials, many questions remain (6, 7, 9). With oxygenation data included in the propensity matching, these data provide a stronger case against HFOV and address a major criticism levied against the study by Gupta and colleagues (10–12). However, a key question is whether the worse outcomes of early HFOV as seen in this study are related to HFOV or the manner in which this modality was used.

Variation in clinical practice regarding HFOV acceptance, application, and management has occurred since the introduction of HFOV (1). This variability allowed for meaningful outcome comparisons because similarly sick children were not treated the same at different sites. It could be postulated that high-usage centers would have better outcomes from more familiarity and experience, but outcomes did not differ when comparing high-usage sites with low-usage sites.

We confirm that early HFOV is used predominantly in patients with severe PARDS, particularly with extremely high OI/OSI values. Worst OI/OSI on Days 0 or 1, which has been shown in children to be a strong predictor of risk of mortality (23), was the most significant predictor of early HFOV in this cohort. Despite our efforts at matching, early HFOV patients in the highest risk quintile had significantly higher OI values compared with CMV/late HFOV patients. Comparing patients at such degrees of severity of illness has difficulties because multisystem organ failure likely results from profound hypoxia. More importantly, however, in the second highest risk quintile, each group had similarly severe OI/OSI values and the findings of longer mechanical ventilation in the early HFOV group was more apparent. Again, it remains unclear whether these results are based on inherent effects of HFOV or the manner in which this modality was applied.

This study implemented a novel approach of including all late HFOV patients in the CMV cohort for several reasons. First, this allowed us to focus on a sample of patients exposed to the potential benefits of HFOV from close to the initiation of mechanical support of ventilation. Second, patients managed with HFOV late in their illness exhibited a significantly longer duration of mechanical ventilation and including them in the CMV cohort avoided a potential bias favoring CMV. Third, late HFOV patients had already been exposed to CMV, for better or worse. Finally, only 6% of the CMV group received late HFOV and any separate analysis of late HFOV would be underpowered to determine a treatment effect. Of note, only 21 (18%) and 17 (10%) of the patients in the two highest quintiles received late HFOV.

There are several possible explanations for the longer days of mechanical ventilation in the early HFOV cohort. The change in practice in the management of CMV over the last 15 years, with an emphasis on low tidal volumes (5), may have decreased the harm related to CMV and, thus, attenuated the initial benefits of HFOV as seen in earlier studies (3). Furthermore, HFOV may cause a direct lung injury and, thus, prolong lung recovery. However, animal studies do not support this hypothesis (24–26), and human data do not exist.

The overall management strategies of mechanical ventilation may differ with HFOV as compared with CMV. For example, clinicians are often hesitant to wean the MAP during HFOV based on a fear of lung derecruitment. Also, endotracheal tube suctioning likely occurs less frequently with HFOV, and the changes in tidal volume based on variable management of the ventilatory frequency could alter the outcome.

Respiratory monitoring varies considerably between HFOV and CMV. End-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring as a guide to ventilator management is absent during HFOV and transcutaneous monitoring is seldom used in the pediatric population. Similarly, assessments of tidal volume delivery are absent with HFOV. Additionally, sedation practice is generally more liberal with HFOV. Short-term use of NMB early in the course of mechanical ventilation has been shown to improve outcome in adults with ARDS (27). This limited use is not what we found for our early HFOV cohort, where the upper-risk quintiles received NMB for a median 53% of their ventilation time. Pediatric studies of prolonged use of NMB have shown increased mortality (28), duration of mechanical ventilation, and frequency of ventilator associated pneumonia (29).

There are important limitations of this study. HFOV use was not randomized, and HFOV management varied among patients and centers. The decision to transition a patient from CMV to HFOV remained in the hands of the practitioners, as did the decision to transition to CMV. In any such study, latent variables, such as individual practitioner preferences, are uncontrolled variables. It is possible that clinicians chose HFOV for one patient over another based on variables not contained in the RESTORE database. As one such example, the OI or OSI values, which was the strongest predictor of early HFOV in this study, has been reported to be a significant factor for HFOV initiation, but up to 44% of surveyed pediatric intensivists use other undefined factors in deciding when to initiate HFOV (1). Additionally, the approach taken to the propensity scoring did not account for a patient’s trajectory of illness. The RESTORE dataset collected worst OI/OSI on day of intubation and daily values thereafter, hence limiting our categorization of the level of oxygenation failure at the precise time of conversion to HFOV. We tried to overcome this potential limitation by analyzing the early use of HFOV instead of any HFOV use. Furthermore, we used each patient’s worst OI during the described timeframe to most closely approximate the decision to initiate early HFOV.

Low tidal volumes have been associated with improved outcomes in adults, and the change in pressure needed for ventilation (delta P) has been reported as a significant factor in mortality (30). It is possible that the CMV group was managed to minimize possible deleterious effects by limiting airway pressures, but not the HFOV group.

Conclusions

Our analyses of the RESTORE database of prospectively collected patient variables and ventilator settings demonstrate a clinically and statistically significant negative impact of early HFOV in children with moderate to severe PARDS. Early HFOV was associated with longer days of mechanical ventilation, longer time to recovery from acute respiratory failure, and higher sedative and NMB use. Although not a randomized controlled trial comparing two modes of ventilation, the results of this propensity score analysis, which included important oxygenation variables, make supporting the current approach to HFOV less convincing. HFOV may have a role in the management of PARDS at the time of peak of lung injury followed by aggressive weaning with lung recovery and a more rapid conversion to CMV. The application of HFOV for PARDS may not be fully assessed until we have a high-quality randomized controlled trial.

Footnotes

Supported by NHLBI and the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (U01 HL086622, M.A.Q.C.; U01 HL086649, D.W.).

Author Contributions: All authors fulfill criteria for authorship by substantial contributions to conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; drafting of the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be asccountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1381OC on October 23, 2015

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Santschi M, Randolph AG, Rimensberger PC, Jouvet P Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Mechanical Ventilation Investigators. Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators Network; European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care. Mechanical ventilation strategies in children with acute lung injury: a survey on stated practice pattern. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:e-332–e-337. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31828a89a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santschi M, Jouvet P, Leclerc F, Gauvin F, Newth CJ, Carroll CL, Flori H, Tasker RC, Rimensberger PC, Randolph AG PALIVE Investigators; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators Network (PALISI); European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) Acute lung injury in children: therapeutic practice and feasibility of international clinical trials. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:681–689. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181d904c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold JH, Hanson JH, Toro-Figuero LO, Gutiérrez J, Berens RJ, Anglin DL. Prospective, randomized comparison of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation and conventional mechanical ventilation in pediatric respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1530–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold JH, Anas NG, Luckett P, Cheifetz IM, Reyes G, Newth CJ, Kocis KC, Heidemann SM, Hanson JH, Brogan TV, et al. High-frequency oscillatory ventilation in pediatric respiratory failure: a multicenter experience. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3913–3919. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200012000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferguson ND, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Mehta S, Hand L, Austin P, Zhou Q, Matte A, Walter SD, Lamontagne F, et al. OSCILLATE Trial Investigators; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. High-frequency oscillation in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:795–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young D, Lamb SE, Shah S, MacKenzie I, Tunnicliffe W, Lall R, Rowan K, Cuthbertson BH OSCAR Study Group. High-frequency oscillation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:806–813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cools F, Askie LM, Offringa M, Asselin JM, Calvert SA, Courtney SE, Dani C, Durand DJ, Gerstmann DR, Henderson-Smart DJ, et al. PreVILIG collaboration. Elective high-frequency oscillatory versus conventional ventilation in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patients’ data. Lancet. 2010;375:2082–2091. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta P, Green JW, Tang X, Gall CM, Gossett JM, Rice TB, Kacmarek RM, Wetzel RC. Comparison of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation and conventional mechanical ventilation in pediatric respiratory failure. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:243–249. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kneyber MC, van Heerde M, Markhorst DG. It is too early to declare early or late rescue high-frequency oscillatory ventilation dead. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:861. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Essouri S, Emeriaud G, Jouvet P. It is too early to declare early or late rescue high-frequency oscillatory ventilation dead. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:861–862. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rimensberger PC, Bachman TE. It is too early to declare early or late rescue high-frequency oscillatory ventilation dead. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:862–863. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curley MAQ, Wypij D, Watson RS, Grant MJC, Asaro LA, Cheifetz IM, Dodson BL, Franck LS, Gedeit RG, Angus DC, et al. RESTORE Study Investigators and the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators Network. Protocolized sedation vs usual care in pediatric patients mechanically ventilated for acute respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:379–389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiser DH. Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 1992;121:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. PRISM III: an updated Pediatric Risk of Mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:743–752. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khemani RG, Smith LS, Zimmerman JJ, Erickson S Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference Group. Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: definition, incidence, and epidemiology. Proceedings from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(Suppl 1):S23–S40. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:2–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoenfeld DA, Bernard GR ARDS Network. Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1772–1777. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridout MS, Demétrio CG, Firth D. Estimating intraclass correlation for binary data. Biometrics. 1999;55:137–148. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ukoumunne OC. A comparison of confidence interval methods for the intraclass correlation coefficient in cluster randomized trials. Stat Med. 2002;21:3757–3774. doi: 10.1002/sim.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Agostino RB., Jr Propensity scores in cardiovascular research. Circulation. 2007;115:2340–2343. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yehya N, Servaes S, Thomas NJ. Characterizing degree of lung injury in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:937–946. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von der Hardt K, Kandler MA, Fink L, Schoof E, Dötsch J, Brandenstein O, Bohle RM, Rascher W. High frequency oscillatory ventilation suppresses inflammatory response in lung tissue and microdissected alveolar macrophages in surfactant depleted piglets. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:339–346. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000106802.55721.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin X, Fu W, Zhao Y, Meng Q, You C, Yu Q.Ultrastructural study of alveolar epithelial type II cells by high-frequency oscillatory ventilation Biomed Res Int 2013. 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa R, Koizumi T, Ono K, Yoshikawa S, Tsushima K, Otagiri T. Effects of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation on oleic acid-induced lung injury in sheep. Lung. 2008;186:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s00408-008-9102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papazian L, Forel JM, Gacouin A, Penot-Ragon C, Perrin G, Loundou A, Jaber S, Arnal JM, Perez D, Seghboyan JM, et al. ACURASYS Study Investigators. Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1107–1116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin LD, Bratton SL, Quint P, Mayock DE. Prospective documentation of sedative, analgesic, and neuromuscular blocking agent use in infants and children in the intensive care unit: a multicenter perspective. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001;2:205–210. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Da Silva PS, Neto HM, de Aguiar VE, Lopes E, Jr, de Carvalho WB. Impact of sustained neuromuscular blockade on outcome of mechanically ventilated children. Pediatr Int. 2010;52:438–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amato MBP, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, Brochard L, Costa EL, Schoenfeld DA, Stewart TE, Briel M, Talmor D, Mercat A, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1410639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]