Abstract

Recent studies provide evidence that premature maternal decidual senescence resulting from heightened mTORC1 signaling is a cause of preterm birth (PTB). We show here that mice devoid of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) with elevated levels of N-arachidonyl ethanolamide (anandamide), a major endocannabinoid lipid mediator, were more susceptible to PTB upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge. Anandamide is degraded by FAAH and primarily works by activating two G-protein-coupled receptors CB1 and CB2, encoded by Cnr1 and Cnr2, respectively. We found that Faah−/− decidual cells progressively underwent premature senescence as marked by increased senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining and γH2AX-positive decidual cells. Interestingly, increased endocannabinoid signaling activated MAPK p38, but not p42/44 or mTORC1 signaling, in Faah−/− deciduae, and inhibition of p38 halted premature decidual senescence. We further showed that treatment of a long-acting anandamide in wild-type mice at midgestation triggered premature decidual senescence utilizing CB1, since administration of a CB1 antagonist greatly reduced the rate of PTB in Faah−/− females exposed to LPS. These results provide evidence that endocannabinoid signaling is critical in regulating decidual senescence and parturition timing. This study identifies a previously unidentified pathway in decidual senescence, which is independent of mTORC1 signaling.

Keywords: anandamide (N-arachidonoylethanolamine) (AEA), cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1), fatty acid metabolism, pregnancy, senescence

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB)3 is reflected in low birth weight and immaturity of multiple organs, particularly the respiratory system. PTB accounts for about 12% of all births in humans (∼12 million babies per year) and is the leading cause of neonatal death with 1 million neonatal deaths per year (1). Although United States health care has made significant advances, the rate of PTB has remained around 11% since 1990 (2, 3). The failure to substantially reduce the incidence of PTB is attributed to multiple etiologies, including decidual senescence, genetic disposition, infection/inflammation, stress, and environmental insults (4–6).

Recent evidence shows a critical role of maternal decidua in PTB (6, 7). Maternal decidual cells are derived from uterine stromal cells. After placentation, the decidua in the mesometrial side functions as an anchoring dock for the feto-placental unit and provides a buffer zone between the myometrium and placental trophoblasts to regulate appropriate trophoblast invasion. Trophoblasts invade the maternal decidual zone and remodel maternal blood vessels to establish the maternal-fetal exchange system that provides nutrition and oxygen to the fetus. Maternal decidual cells undergo progressive senescence with approaching parturition (4). At midgestational stage, the decidua helps stabilize the placenta; prior to the onset of parturition, the decidual layer thins to facilitate the parturition process. Evidence in mice with uterine inactivation of p53 shows that one major cause of PTB is premature decidual senescence which becomes more aggravated by an inflammatory stimulus (5).

Marijuana is the most frequently used illicit drug during pregnancy, and cannabinoids/endocannabinoids have been shown to influence various reproductive events (8). However, the role of cannabinoids or endocannabinoids signaling in parturition and PTB is not known. In the early 1990's, discovery of several endogenous cannabis-like compounds and their target receptors greatly advanced the research on cannabinoid signaling. N-Arachidonoyl ethanolamide (AEA, popularly known as anandamide) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) are the two most studied endocannabinoids (9, 10). Both of them target two G-protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors: Cnr1 encoding CB1 (11, 12) and Cnr2 encoding CB2 (13). Although AEA is considered to be produced primarily from N-arachidonoylphosphatidylethanolamine (NAPE) by NAPE-hydrolyzing phospholipase D (14), other pathways can also contribute to AEA synthesis (15, 16). AEA is degraded to ethanolamine and arachidonic acid by a membrane-bound fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) (17). Although FAAH can hydrolyze other N-acyl ethanolamine (NAE) lipids and to a lesser extent 2-AG (18), studies in Faah−/− mice have shown that FAAH regulates the magnitude and duration of AEA signaling via activation of CB receptors (15, 19). The activation of CB1 and CB2 exert different biological effects in a cell-type specific manor. Coupling with Gi/o or Gq proteins, CB1 and CB2 could regulate Ca2+ channels (20, 21), inhibit adenylyl cyclase (12, 22) and stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) including ERK, JNK, and p38 (21, 23–25).

We explored the role of sustained and increased endocannabinoid signaling on parturition. We used Faah mutant mice that are continually exposed to higher AEA levels, which activate CB receptors in a similar manner to exogenous cannabinoid ligands, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol present in marijuana and synthetic cannabinoids (19). We found that Faah−/− mice have comparable gestational lengths to wild-type (WT) mice. Since lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can activate Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and evoke release proinflammatory cytokines in the uterus and fetal membrane to induce preterm birth in mice and non-human primates (26), we used widely used LPS-induced preterm birth model to study the role of cannabinoid signaling in preterm birth in mice. After LPS challenge, Faah−/− females became more susceptible to PTB compared with their WT counterparts. We found that the elevated endocannabinoid signaling in Faah−/− mice leads to premature decidual senescence via increased MAPK signaling (phospho-p38, p-p38) levels in the decidua, resulting in higher sensitivity to LPS-induced PTB.

Experimental Procedures

Animals and Treatments

WT, Faah−/−, and Cnr1−/− mice and their littermates were housed in the animal care facility at the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center according to NIH and institutional guidelines for laboratory animals. Faah−/− and Cnr1−/− mice were generated as described (19, 27). All protocols of the present study were approved by the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Female mice were mated with WT fertile males to induce pregnancy (vaginal plug = day 1 of pregnancy). Parturition events were monitored from days 17 through 21 by observing mice daily in the morning and evening. PTB was defined as birth occurring earlier than day 19. Ultrapure LPS (E. coli 0111:B4, tlrl-3pelps, Invivogen) were dissolved in saline and given intraperitoneally in the morning of day 16. Pregnant Faah−/− females were treated with a p38 inhibitor, SB203580 (500 μg/mouse/day, Cayman) or SR141716 (100 μg/mouse/day, NIDA) on days 10, 12, 14, and 16 of pregnancy, and tissues were collected on day 16 or examined for parturition timing. Pregnant WT females were treated with methanandamide (150 μg/mouse/day, Cayman) or URB597 (60 μg/mouse/day, Cayman) on days 10, 12, 14, and 16 of pregnancy.

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (28). In brief, frozen sections (12 μm) were mounted onto poly-l-lysine-coated slides and fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The sections were prehybridized and hybridized at 45 °C for 4 h in 50% (v/v) formamide hybridization buffer containing 35S-labeled antisense RNA probes. The probe for Ptgs2 and Plpj (a gift from Michael Soares, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas) was synthesized as previously described (5, 29). RNase A-resistant hybrids were detected by autoradiography. Sections were post-stained with H&E.

Measurement of Estradiol-17β (E2) and P4 Levels

Serum levels of E2 and P4 were measured by Enzyme Immunoassay kits (Cayman).

SA-β-gal Staining

Staining of SA-β-gal activity was performed as described previously (7). The staining was performed at pH 5.5. To compare the intensity of SA-β-gal staining, sections from different genotypes and on different days of pregnancy were processed on the same slide.

Measurement of N-Acyl Ethanolamines, 2-Acyl-sn-glycerol and Prostaglandins Profiles

Maternal decidual tissues of implantation sites were collected on day 16 of pregnancy. These tissues were flash frozen and stored at −80 °C until used for extractions. Methanolic extracts of tissues were partially purified using C18 solid-phase extraction columns (Agilent), and prostaglandins were quantified by HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry as previously described (7, 30).

Immunostaining

Immunostaining of Cytokeratin 8 (the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa), γH2AX (Millipore), and p-p38 (Cell signaling) was visualized using a Histostain-Plus (diaminobenzidine) kit (#2014, Invitrogen). Immunofluorescence for γH2AX (Millipore) was performed using a secondary antibody Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (Jackson Immuno Research). Nuclear staining was by Hoechst 33342 (H1399, Molecular Probes, 2 μg/ml). Immunofluorescence was performed on fresh-frozen sections. Sections were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation in secondary antibody for 1 h in PBS. Immunofluorescence was visualized under a confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000). Quantitative analysis was performed using Nikon NIS Elements Advanced Research software.

Western Blotting

Protein extraction and Western blotting were performed as previously described (31, 32). Antibodies to p38, p-p38, S6, p-S6, p42/44, p-p42/4, MAPKAPK2, and p-MAPKAPK2 were obtained from Cell Signaling. Bands were visualized by using an ECL Prime Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare).

Quantitative PCR

RNA was prepared from homogenized tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA extraction was performed as described previously (7, 31). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosciences). PCR was performed using the following primers: p16, ATCTGGAGCAGCATGGAGTC and GCAGAAGAGCTGCTACGTGA; Foxo1, AAGAGCGTGCCCTACTTCAA and CTCCCTCTGGATTGAGCATC; p21, GTACTTCCTCTGCCCTGCTG and TCTGCGCTTGGAGTGATAGA; Cnr1, TCTTAGACGGCCTTGCAGAT andAATTCTCCCCACACTGGATG; Prl8a2, GGGAGAAAGCTGCATCAATTCCT and GCTCTGAGAACCTCCTCATCACG; Plpj, TTCTGGAGGGAGCAAAAGC and CCACCTGTCAGGCTCGTTAT; Gapdh, TGTTCCTACCCCCAATGTGT and AGGAGACAACCTGGTCCTCA. Gapdh served as housekeeping genes for mouse tissues or cells.

Cell Culture and in Vitro Decidualization

Stromal cells were collected by enzymatic digestion of WT uteri on day 4 of pregnancy as described previously (33). The cells were cultured in phenol-red free DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with charcoal-stripped 1% FBS (w/v) overnight prior to the initiation of decidualization by treatment of E2 (10 nm) and Medroxyprogesterone acetate (1 μm).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t test and Chi-square test. p < 0.05 was considered significant. Values are mean ± S.E.

Results

Mice Exposed to Higher Endocannabinoid Signaling Are Susceptible to Inflammation-induced PTB

To study the effects of elevated endocannabinoid signaling in mouse parturition timing, WT and Faah−/− females were mated with WT males. In this breeding scheme, placentas and fetuses are heterozygous, and maternal deciduae are FAAH deficient. To confirm placentation was not affected, histology of the implantation sites was examined on day 14 of pregnancy; cytokeratin staining was used to demarcate trophoblast derived cells. Trophoblast cells in the labyrinth and spongy layers of the placenta and those cells invading the maternal decidual zone were cytokeratin positive (Fig. 1A). No obvious differences in placentation and trophoblast invasion were observed in WT and Faah−/− females. A marker of the spongy layer Plpj was further examined by in situ hybridization and real time PCR on day 16 of pregnancy (5). The signal intensity and pattern of Plpj expression were comparable between WT and Faah−/− implantation sites (Fig. 1, B and C). These results suggested that placental development in Faah−/− is comparable to that in WT. Faah−/− females have a gestational length (∼19.8 days) that closely matches that of WT females in our barrier mouse facility. However, an intraperitoneal injection of 25 μg of LPS on day 16 of pregnancy resulted in 80% of Faah−/− females undergoing PTB with no surviving pups as opposed to only 43% of WT females experiencing PTB at this LPS dose (Fig. 1D). When the dose of LPS was raised to 37 μg, the PTB rate increased to 64 and 86% in WT and Faah−/− females, respectively. Since the responses to 25 μg of LPS showed a larger difference in PTB rates between WT and Faah−/− females, this LPS dose was used in all subsequent in vivo experiments. To confirm that maternal decidual levels of endocannabinoids were elevated in Faah−/− females, the AEA and 2-AG levels in maternal decidual tissues were measured 12 h after vehicle or LPS (25 μg) injections. We found that 2-AG, and other 2-acyl-sn-glycerol levels, showed no significant changes in Faah−/− decidua as compared with those in WT mice in vehicle-treated groups, but as expected, levels of AEA and other NAEs were significantly elevated (Fig. 2, A and B). Importantly, the levels of all NAEs, including AEA, were higher after LPS stimulation in WT and Faah−/− deciduae (Fig. 2B), whereas levels of 2-AG or other 2-acyl-sn-glycerols showed little or no changes after LPS challenge (Fig. 2A). Consistent with our previous observation (34), the results indicate that FAAH is a major regulator of tissue levels of NAEs. Increases in NAEs after LPS challenge were reported in a recent study (35). This suggests that NAEs acutely respond to LPS challenge by a mechanism not yet clearly understood. Collectively, the results demonstrate that the increased rate of LPS-induced PTB occurs in Faah−/− mice with higher levels of NAEs.

FIGURE 1.

Faah−/− females are susceptible to inflammation-induced PTB. A, immunohistochemistry of CK8 on day 16. Signals highlighted all trophoblast cells. Dotted lines demarcate the border between maternal and fetal tissues. Some trophoblast cells migrated into maternal decidual zone in WT and Faah−/− mice. B, in situ hybridization and (C) qPCR of PlPj on day 16 implantation sites (mean ± S.E.). D, PTB rates of WT and Faah−/− mice 12 h after LPS injection (*, p < 0.05, Chi-square test). Dec, decidua; Sp, spongy layer; Lab, Labyrinth zone.

FIGURE 2.

Levels of 2-acyl-sn-glycerol and N-acyl ethanolamine with or without LPS challenge in maternal decidua on day 16. Levels of 2-acyl-sn-glycerol (A) and N-acyl ethanolamine (B) with or without LPS challenge in maternal decidua on day 16 (mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05, Student's t tests).

Enhanced Endocannabinoid Signaling Imposes Premature Decidual Senescence

Higher serum P4 levels maintain myometrial quiescence during pregnancy. LPS-induced inflammation promptly causes a fall in P4 levels (36), which predispose pregnant females to PTB (37). To examine whether the higher sensitivity to LPS in Faah−/− mice correlated with ovarian hormone production, we quantified serum levels of estradiol-17β (E2) and P4 12 h after LPS injection on day 16. Although LPS challenge significantly decreased P4 levels in both Faah−/− and WT mice, the levels were comparable between the two groups (Fig. 3A). E2 levels in WT and Faah−/− females were also comparable after LPS injection. Since the decreases in P4 levels are considered to be a major cause of preterm birth, we tried to rescue the phenotype in Faah−/− females by supplementing P4 (1 mg) 3 h before and 6 h after LPS injection. Although P4 supplement efficiently decreased preterm labor, but intra-uterine resorption of implantation sites was observed in 8 out of 12 Faah−/− females.

FIGURE 3.

Faah−/− decidua undergo premature decidual senescence. A, serum P4 and E2 levels 12 h after LPS or saline injection on day 16 of pregnancy. Faah−/− and WT mice had comparable P4 and E2 levels (mean ± S.E.). B, in situ hybridization of Ptgs2 on day 16 implantation sites 12 h after LPS injection. WT and Faah−/− mice had comparable Ptgs2 signals. C, profiles of prostaglandins in maternal decidua 12 h after LPS injection on day 16 (mean ± S.E.). D, SA-β-gal staining (blue) in sections of WT and Faah−/− implantation sites 12 h after LPS or saline injection on day 16 of pregnancy. Cellular senescence was higher in Faah−/− as compared with WT decidua with saline treatment as evident from higher SA-β-gal activity. After LPS injection, SA-β-gal activity was increased in WT and Faah−/− decidua as compared with those treated with saline. Note reduced decidual thickness in Faah−/− decidua after LPS injection. Decidual thickness is marked by vertical lines. E, SA-β-gal staining (blue) in sections of WT and Faah−/− implantation sites on day 12 of pregnancy. Images presented in panels D and E are representative of three independent implantation sites in each group. F, increased signals for γH2AX, a senescence and DNA damage response marker, was observed in Faah−/− decidua. The framed area is shown in high magnification and quantification of γH2AX-positive cells is shown in panel G (mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05, Student's t tests). Dec, decidua; Sp, spongy layer; Lab, Labyrinth zone.

Prostaglandins (PGs) play a major role in parturition. There is evidence that PGE2, PGF2α, and PGI2 are up-regulated in the uterus and decidua at the onset of parturition (38), and enhance the contractile response/activity in the myometrium (39, 40). Cyclooxygenases, Ptgs1 (Cox1) and Ptgs2 (Cox2) are two major enzymes that catalyze PG biosynthesis. Ptgs1 is considered to be constitutively expressed in many tissues, while Ptgs2 is induced by growth factors, cytokines, and various inflammatory stimuli (41). Our previous studies in p53d/d mice indicated that Ptgs2 is activated after LPS challenge in decidual cells (5, 7). Therefore, we examined the expression of Ptgs2 on day 16 by in situ hybridization in WT and Faah−/− implantation sites 12 h after LPS challenge. We found that Ptgs2 expression was noted at the maternal-conceptus interface, primarily in the decidual cells, but the expression pattern and signal intensity were comparable in WT and Faah−/− implantation sites (Fig. 3B). This observation was reflected in levels of PGE2, PGF2α and 6-keto-PGF1α (the stable metabolite of PGI2) as measured by LC-MS Mass Spectrometry (35) (Fig. 3C). These results implicate that increased PG levels were not the reason for enhanced susceptibility of Faah−/− mice to LPS-induced PTB.

While approaching parturition, decidual cells undergo progressive senescence as marked by gradual increases in senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining (4). Our previous study showed that premature decidual senescence increases the risk of PTB (7). Therefore, we examined SA-β-gal staining in WT and Faah−/− females. We found that Faah−/− decidual cells have increased SA-β-gal staining on days 12 and 16 of pregnancy (Fig. 3, D and E), suggesting that decidual cells undergo premature senescence under elevated endocannabinoid signaling. After LPS challenge, the SA-β-gal staining was significantly increased in WT decidual cells. In Faah−/− females, SA-β-gal signal intensity was also higher. Interestingly, the area of the decidual zone was greatly reduced after LPS injections, suggesting that senescent Faah−/− decidual cells rapidly deteriorated in response to LPS challenge (Fig. 3D). To further explore this finding, we examined γH2AX expression, another marker of senescence associated with DNA damage response (42). The number of γH2AX-positive decidual cells in Faah−/− females was substantially higher compared with the WT decidual bed (Fig. 3, F and G). These results suggest Faah−/− decidual cells undergo premature senescence and are susceptible to LPS challenge.

Endocannabinoid Signaling Activates p38 MAPK Signaling and Advances Decidual Senescence

Many pathways have been shown to actively participate in senescence, including p16, p21, p38, and Foxo1 (43, 44). Our recent work showed that activation of Akt-mTOR-p21 signaling axis in deciduae leads to premature senescence (4). To further investigate the mechanism of premature senescence in Faah−/− females, we examined the levels of p16, p21, Foxo1, and mTORC1 signaling by either qPCR or Western blotting. There were no significant differences in levels of p16, p21, and Foxo1 in decidual samples from WT and Faah−/− females on day 16 (Fig. 4A). Although mTORC1 activation in p53d/d mice plays a key role in mediating the decidual senescence (5), the activity of mTORC1 as shown by pS6 levels was comparable in WT and Faah−/− decidual tissues (Fig. 4B). MAP kinases including phosphop38 (p-p38) and p42/44 are known to mediate cannabinoid receptor signaling (45), and they can induce cellular senescence (44). We used Western blotting to examine the activation of p38 and p42/44 in day 16 decidual tissues of WT and Faah−/− females and found that activation of p38, but not p42/44, was higher in Faah−/− decidual tissues (Fig. 4C). An elevation of p-p38 was also noted in day 12 Faah−/− decidual tissues. To identify the location of cells with activated p38, we performed immunohistochemistry of p-p38 in day 16 WT and Faah−/− implantation sites. The p-p38 positive signals were mainly located in the decidual zone close to the mesometrial side (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Higher endocannabinoid signaling induces activation of p38 MAPK in the decidua. A, RNA levels of p16, Foxo1 and p21 in WT and Faah−/− decidual tissues (mean ± S.E.). B, Western blotting and quantification of band intensities of pS6 in WT and Faah−/− decidual tissues on day 16. C, Western blotting results show p-p38 levels were higher in days 12 and 16 Faah−/− decidual tissues, whereas p-p42/44 levels were comparable in WT and Faah−/− decidua on day 16 of pregnancy (mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05, Student's t tests). D, immunostaining of p-p38 showed that more p-p38 positive cells were observed in Faah−/− decidual cells. The framed area is shown in high magnification. Arrows point to p-p38 positive cells. Dec, decidua; M, mesometrial side; AM, anti-mesometrial side. E, Western blotting of p-MAPKAPK2 and p-p38 using SB203580 or vehicle-treated Faah−/− decidual tissues on day 16. F, SA-β-gal activity was inhibited by SB203580, a p38 inhibitor, in day 16 pregnant Faah−/− decidual cells.

The above results further prompted us to ask whether elevated activation of p38 in Faah−/− females induced premature senescence. Pregnant Faah−/− females were treated with a p38 inhibitor, SB203580, on days 10, 12, and 14 of pregnancy, and tissues were collected on day 16. The treatment of SB203580 did not change the phosphorylation or total amount of p38, but efficiently inhibited p38 function as evident from decreased activation of MAPKAPK2, a direct target of p38 (Fig. 4E). Faah−/− females treated with SB203580 showed attenuated decidual senescence on day 16 (Fig. 4F). After LPS injection on day 16, 2 of 8 Faah−/− females pretreated treated with SB203580 showed preterm birth. Mice not showing preterm birth mostly produced live pups. The rate of preterm birth in pretreated with SB203580 was much lower as compared with non-treated counterparts (25% versus 80%).

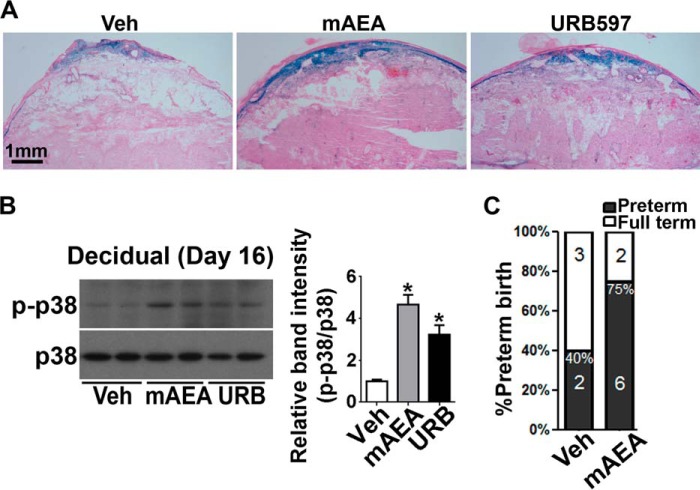

Wild-type Females Exposed to Higher Endocannabinoid Signaling Show Premature Decidual Senescence at Midgestation

Using Faah−/− females, we have shown here that decidual cells undergoing premature senescence in these mice which are consistently exposed throughout their lifetime to higher endocannabinoid/NAE signaling. We asked whether WT mice with short term exposure to higher endocannabinoids/NAEs would show similar premature decidual senescence during the late gestational stage. Pregnant WT females were treated with URB597, a selective FAAH inhibitor, or vehicle from days 10 to 15, and implantation sites were collected on day 16. The decidual cells treated by URB597 showed higher SA-β-gal staining (Fig. 5A). Although our mass-spectrometry data show increased levels of a panel of NAEs in Faah−/− decidua, AEA is considered the most biologically active NAE toward CB receptors. To see if higher AEA levels would cause premature decidual senescence, pregnant WT females were treated with methanandamide (mAEA), a stable AEA analogue or vehicle from days 10 to 15, and implantation sites were collected on day 16. SA-β-gal staining showed mAEA induced premature decidual senescence in WT females (Fig. 5A). Similar to Faah−/− decidua, decidual protein extracts from implantation sites treated with either mAEA or URB597 exhibited higher p-p38 levels in WT females (Fig. 5B), and mice exposed to mAEA were more susceptible to LPS induced PTB (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that decidual cells with acute exposure to higher AEA signaling during midgestation undergo premature decidual senescence, increasing the risk of PTB after LPS challenge.

FIGURE 5.

Mid-gestational exposure to elevated levels of anandamide advances decidual senescence in WT mice. A, blocking FAAH activity or treatment with mAEA increased SA-β-gal activity in WT decidual cells. Treatment of URB597, a FAAH inhibitor, or mAEA from days 10 to 16 increased decidual senescence in WT mice. B, Western blotting and quantification results show that treatment with URB597 or mAEA increased p-p38 levels in WT decidual tissues (mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05, Student's t tests). C, pregnant mice treated with mAEA shows higher PTB rates after LPS challenge (*, p < 0.05, Chi-square test).

Anandamide Induces Senescence in Decidual Cells in Vitro

To investigate whether endocannabinoid signaling targets decidual cells directly, we generated decidual cells from primary stromal cells by steroid hormones in vitro (33). Stromal differentiation to decidual cells was validated by monitoring the expression of prolactin family 8 subfamily member 2 (Prl8a2), a known marker of decidualization in mice (46). Prl8a2 was induced in decidualized cells 3 days after hormone treatment (Fig. 6A). Similar to our in vivo results, mAEA activated p38 signaling in decidual cells (Fig. 6B). To test whether higher endocannabinoid signaling induces decidual cell senescence in culture, we cultured decidual cells in the presence of 5 μm mAEA. Indeed, cells exposed to mAEA showed higher SA-β-gal staining (Fig. 6C), providing evidence that mAEA induces cellular senescence in decidualizing cells. These results were further reflected in higher number of γH2AX-positive decidual cells after mAEA exposure (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that mAEA directly targets mouse decidual cells to activate p38 signaling and induces decidual cell senescence.

FIGURE 6.

Anandamide induces cellular senescence in decidual cells in vitro via targeting CB1. A, RT-PCR results show Prl8a2 expression. Expression of Prl8a2, a decidual cell marker, was observed in decidualized stromal cells 3 days or 5 days after hormone induction. B, Western blotting results show that mAEA increased p-p38 levels in WT decidual cells in vitro, which is quantified in a bar diagram (mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05, Student's t tests). C, mAEA increased SA-β-gal activity and γH2AX expression in decidualized primary stromal cells in vitro; data on quantitation are shown in bar diagrams (mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05, Student's t tests). D, Cnr1 is expressed in decidualized stromal cells. Cnr1 transcripts were present in decidualized stromal cells 3 days or 5 days after hormone induction. WT (Br) and Cnr1−/− brain tissues were used as positive and negative controls. E and F, Western blotting and quantification of data show that SR1 but not SR2 prevented the increase in p-p38 levels in primary stromal cells decidualized in vitro (mean ± S.E.; *, p < 0.05, Student's t tests). G, pregnant Faah−/− mice treated with SR1 showed lower PTB rates compared with those treated with vehicle after LPS injection on day 16 of pregnancy (*, p < 0.05, Chi-square test).

Activation of p38 by Endocannabinoids Is Mediated by CB1

Endocannabinoids and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the active component of marijuana, operate through two G protein-coupled receptors, CB1 and CB2. CB1 has been identified in human maternal decidual cells (47). We observed that Cnr1 RNA expression 3 days after stromal cell induction to decidualization in vitro (Fig. 6D). To identify which CB receptor type mediates AEA signaling, we treated decidual cells with SR141716 (SR1, a CB1 antagonist) or SR144528 (SR2, a CB2 antagonist) in the presence or absence of mAEA. We found that only SR1, but not SR2, reversed the activation of p38 by mAEA (Fig. 6, E and F), suggesting that mAEA activates p38 signaling via CB1. This in vitro data prompted us to ask whether we could reverse the phenotype in Faah−/− females. Pregnant Faah−/− females were treated with SR1 or vehicle from days 10 to 16, and challenged by LPS on day 16. Faah−/− females treated by SR1 showed much lower PTB rate after LPS challenge (Fig. 6G). We also used mice with deletion of both Faah and Cnr1 (Faah−/−/Cnr1−/−). However, deletion of Cnr1 did not reverse the phenotype of Faah−/− females. After the mice were challenged with LPS (25 μg) on day 16, 85% of Faah−/−/Cnr1−/− females experienced preterm delivery, similar to that of Faah−/− females (80%). These observations raise the possibility that short term inhibition of CB1 by SR1 during mid-gestational stage is effective, whereas mice with CB1 deficiency from conception develop other means to transduce signaling. Taken together, mAEA induces decidual senescence via CB1-activated p38 signaling, which can be blocked by a selective CB1 antagonist both in vitro and in vivo.

Discussion

PTB is a syndrome of multiple etiologies (6). One cause of PTB is premature onset of decidual senescence. Our previous and present studies clearly show that more than one signaling pathway can confer premature decidual senescence to trigger PTB. It is intriguing that inactivation of p53 in the uterus causes premature decidual senescence via heightened mTORC1 signaling with associated changes in higher PG levels, whereas premature decidual senescence that results from higher and sustained endocannabinoid signaling is induced by activation of p38 MAPK signaling, making pregnant females more susceptible to PTB by infection/inflammation. The most striking observation is that chronic or short-term exposure to higher endocannabinoid signaling can provoke senescence-induced PTB.

There are two interesting aspects to note in this study. The first is that AEA targets decidual cells directly via CB1 to activate p38 signaling and decidual senescence. Secondly, short-term acute antagonism of CB1 signaling by a specific CB1 antagonist treatment during midgestation provided strong resistance to PTB in LPS exposed Faah−/− females with decreases in decidual senescence. Surprisingly, superimposition of Cnr1 deletion in Faah−/− females did not reverse the phenotype in Faah−/− females exposed to LPS. These observations raise the possibility that mice with life-long CB1 deficiency either adapt to manage the deficiency by utilizing an unidentified signaling system, or that sustained higher AEA and other NAEs exert effects through additional pathways.

Our results show that Faah−/− females show normal gestational length and birth weight under controlled pregnancy environments. However, higher endocannabinoid signaling serves as a catalyst for PTB if the mother is exposed to environmental insults, such as infection/inflammation and other stressors. Information on the impact of cannabinoids on pregnancy may help healthcare providers counsel patients and improve the health and well-being of pregnant patients and their children; here is evidence that enhanced endocannabinoid signaling from reduced expression and activity of FAAH in peripheral lymphocytes is associated with pregnancy loss in humans (48). Notably, aberrant FAAH in maternal lymphocytes is also associated with failure to achieve an ongoing pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (49).

Author Contributions

X. S. and S. K. D. designed research; X. S., W. D., Y. L., S. T., E. L., and H. B. B. performed research; X. S., W. D., E. L., H. B. B., and S. K. D. analyzed data; and X. S., H. B. B., and S. K. D. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgment

We thank Katie A. Gerhardt for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported in parts by grants from NIDA/National Institutes of Health (DA006668, to S. K. D.) and March of Dimes Foundation (21-FY12-127 and 22-FY13-543). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- PTB

- preterm birth

- 2-AG

- 2-arachidonoylglycerol

- AEA

- N-arachidonoyl ethanolamide, also known as anandamide

- CB1

- cannabinoid receptor 1, encoded by Cnr1

- CB2

- cannabinoid receptor 2, encoded by Cnr2

- E2

- estradiol-17β

- FAAH

- fatty acid amide hydrolase

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- NAE

- N-acyl ethanolamine

- P4

- progesterone

- PG

- prostaglandin

- SA-β-Gal

- senescence-associated β-galactosidase.

References

- 1.Behrman R. E., and Butler A. S. (2007) Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention., National Academies Press, Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simhan H. N., and Caritis S. N. (2007) Prevention of preterm delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 477–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics (2015) America'sChildren: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirota Y., Cha J., Yoshie M., Daikoku T., and Dey S. K. (2011) Heightened uterine mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling provokes preterm birth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18073–18078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cha J., Bartos A., Egashira M., Haraguchi H., Saito-Fujita T., Leishman E., Bradshaw H., Dey S. K., and Hirota Y. (2013) Combinatory approaches prevent preterm birth profoundly exacerbated by gene-environment interactions. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 4063–4075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero R., Dey S. K., and Fisher S. J. (2014) Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science 345, 760–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirota Y., Daikoku T., Tranguch S., Xie H., Bradshaw H. B., and Dey S. K. (2010) Uterine-specific p53 deficiency confers premature uterine senescence and promotes preterm birth in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 803–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun X., and Dey S. K. (2012) Endocannabinoid signaling in female reproduction. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 3, 349–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devane W. A., Hanus L., Breuer A., Pertwee R. G., Stevenson L. A., Griffin G., Gibson D., Mandelbaum A., Etinger A., and Mechoulam R. (1992) Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 258, 1946–1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mechoulam R., Ben-Shabat S., Hanus L., Ligumsky M., Kaminski N. E., Schatz A. R., Gopher A., Almog S., Martin B. R., and Compton D. R. (1995) Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 50, 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devane W. A., Dysarz F. A. 3rd, Johnson M. R., Melvin L. S., and Howlett A. C. (1988) Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol. Pharmacol. 34, 605–613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuda L. A., Lolait S. J., Brownstein M. J., Young A. C., and Bonner T. I. (1990) Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 346, 561–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munro S., Thomas K. L., and Abu-Shaar M. (1993) Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 365, 61–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto Y., Morishita J., Tsuboi K., Tonai T., and Ueda N. (2004) Molecular characterization of a phospholipase D generating anandamide and its congeners. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5298–5305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J., Wang L., Harvey-White J., Osei-Hyiaman D., Razdan R., Gong Q., Chan A. C., Zhou Z., Huang B. X., Kim H. Y., and Kunos G. (2006) A biosynthetic pathway for anandamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13345–13350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon G. M., and Cravatt B. F. (2006) Endocannabinoid biosynthesis proceeding through glycerophospho-N-acyl ethanolamine and a role for α/β-hydrolase 4 in this pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26465–26472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cravatt B. F., Giang D. K., Mayfield S. P., Boger D. L., Lerner R. A., and Gilula N. B. (1996) Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature 384, 83–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Marzo V. (1998) 'Endocannabinoids' and other fatty acid derivatives with cannabimimetic properties: biochemistry and possible physiopathological relevance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1392, 153–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cravatt B. F., Demarest K., Patricelli M. P., Bracey M. H., Giang D. K., Martin B. R., and Lichtman A. H. (2001) Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9371–9376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caulfield M. P., and Brown D. A. (1992) Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit Ca current in NG108–15 neuroblastoma cells via a pertussis toxin-sensitive mechanism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 106, 231–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H., Matsumoto H., Guo Y., Paria B. C., Roberts R. L., and Dey S. K. (2003) Differential G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptor signaling by anandamide directs blastocyst activation for implantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14914–14919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paria B. C., Das S. K., and Dey S. K. (1995) The preimplantation mouse embryo is a target for cannabinoid ligand-receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 9460–9464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouaboula M., Poinot-Chazel C., Bourrié B., Canat X., Calandra B., Rinaldi-Carmona M., Le Fur G., and Casellas P. (1995) Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by stimulation of the central cannabinoid receptor CB1. Biochem. J. 312, 637–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rueda D., Galve-Roperh I., Haro A., and Guzmán M. (2000) The CB(1) cannabinoid receptor is coupled to the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 814–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pucci M., Pasquariello N., Battista N., Di Tommaso M., Rapino C., Fezza F., Zuccolo M., Jourdain R., Finazzi Agrò A., Breton L., and Maccarrone M. (2012) Endocannabinoids stimulate human melanogenesis via type-1 cannabinoid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15466–15478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thaxton J. E., Nevers T. A., and Sharma S. (2010) TLR-mediated preterm birth in response to pathogenic agents. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmer A., Zimmer A. M., Hohmann A. G., Herkenham M., and Bonner T. I. (1999) Increased mortality, hypoactivity, and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5780–5785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan J., Paria B. C., Dey S. K., and Das S. K. (1999) Differential uterine expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors correlates with uterine preparation for implantation and decidualization in the mouse. Endocrinology 140, 5310–5321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakraborty I., Das S. K., and Dey S. K. (1995) Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor mRNAs in the mouse uterus around the time of implantation. J. Endocrinol. 147, 339–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H., Guo Y., Wang D., Kingsley P. J., Marnett L. J., Das S. K., DuBois R. N., and Dey S. K. (2004) Aberrant cannabinoid signaling impairs oviductal transport of embryos. Nat. Med. 10, 1074–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie H., Sun X., Piao Y., Jegga A. G., Handwerger S., Ko M. S., and Dey S. K. (2012) Silencing or amplification of endocannabinoid signaling in blastocysts via CB1 compromises trophoblast cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 32288–32297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H., Xie H., Sun X., Tranguch S., Zhang H., Jia X., Wang D., Das S. K., Desvergne B., Wahli W., DuBois R. N., and Dey S. K. (2007) Stage-specific integration of maternal and embryonic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta signaling is critical to pregnancy success. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37770–37782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Kumar R. M., Biggs V. J., Lee H., Chen Y., Kagey M. H., Young R. A., and Abate-Shen C. (2011) The Msx1 homeoprotein recruits Polycomb to the nuclear periphery during development. Dev. Cell 21, 575–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun X., Xie H., Yang J., Wang H., Bradshaw H. B., and Dey S. K. (2010) Endocannabinoid signaling directs differentiation of trophoblast cell lineages and placentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 16887–16892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolfson M. L., Correa F., Leishman E., Vercelli C., Cymeryng C., Blanco J., Bradshaw H. B., and Franchi A. M. (2015) Lipopolysaccharide-induced murine embryonic resorption involves changes in endocannabinoid profiling and alters progesterone secretion and inflammatory response by a CB1-mediated fashion. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 411, 214–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fidel P. I. Jr., Romero R., Maymon E., and Hertelendy F. (1998) Bacteria-induced or bacterial product-induced preterm parturition in mice and rabbits is preceded by a significant fall in serum progesterone concentrations. J. Matern. Fetal Med. 7, 222–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casey M. L., and MacDonald P. C. (1997) The endocrinology of human parturition. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 828, 273–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winchester S. K., Imamura T., Gross G. A., Muglia L. M., Vogt S. K., Wright J., Watanabe K., Tai H. H., and Muglia L. J. (2002) Coordinate regulation of prostaglandin metabolism for induction of parturition in mice. Endocrinology 143, 2593–2598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houlihan D. D., Dennedy M. C., and Morrison J. J. (2010) Effects of abnormal cannabidiol on oxytocin-induced myometrial contractility. Reproduction 139, 783–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dennedy M. C., Friel A. M., Houlihan D. D., Broderick V. M., Smith T., and Morrison J. J. (2004) Cannabinoids and the human uterus during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 190, 2–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith W. L., and Dewitt D. L. (1996) Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2. Adv. Immunol. 62, 167–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sedelnikova O. A., Horikawa I., Zimonjic D. B., Popescu N. C., Bonner W. M., and Barrett J. C. (2004) Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 168–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collado M., and Serrano M. (2006) The power and the promise of oncogene-induced senescence markers. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 472–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Y., Li N., Xiang R., and Sun P. (2014) Emerging roles of the p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in oncogene-induced senescence. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 268–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Howlett A. C. (2005) Cannabinoid receptor signaling. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 53–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alam S. M., Konno T., and Soares M. J. (2015) Identification of target genes for a prolactin family paralog in mouse decidua. Reproduction 149, 625–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park B., Gibbons H. M., Mitchell M. D., and Glass M. (2003) Identification of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) in the human placenta. Placenta 24, 990–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maccarrone M., Valensise H., Bari M., Lazzarin N., Romanini C., and Finazzi-Agrò A. (2000) Relation between decreased anandamide hydrolase concentrations in human lymphocytes and miscarriage. Lancet 355, 1326–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maccarrone M., Bisogno T., Valensise H., Lazzarin N., Fezza F., Manna C., Di Marzo V., and Finazzi-Agrò A. (2002) Low fatty acid amide hydrolase and high anandamide levels are associated with failure to achieve an ongoing pregnancy after IVF and embryo transfer. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 8, 188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]