Tocopherol-like methyltransferases in the Apocynaceae family of angiosperms are monoterpenoid indole alkaloid (MIA)-N-methyltransferases that contribute to chemical and biological diversity of the plants.

Abstract

Members of the Apocynaceae plant family produce a large number of monoterpenoid indole alkaloids (MIAs) with different substitution patterns that are responsible for their various biological activities. A novel N-methyltransferase involved in the vindoline pathway in Catharanthus roseus showing distinct similarity to γ-tocopherol C-methyltransferases was used in a bioinformatic screen of transcriptomes from Vinca minor, Rauvolfia serpentina, and C. roseus to identify 10 γ-tocopherol-like N-methyltransferases from a large annotated transcriptome database of different MIA-producing plant species (www.phytometasyn.ca). The biochemical function of two members of this group cloned from V. minor (VmPiNMT) and R. serpentina (RsPiNMT) have been characterized by screening their biochemical activities against potential MIA substrates harvested from the leaf surfaces of MIA-accumulating plants. The approach was validated by identifying the MIA picrinine from leaf surfaces of Amsonia hubrichtii as a substrate of VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT. Recombinant proteins were shown to have high substrate specificity and affinity for picrinine, converting it to N-methylpicrinine (ervincine). Developmental studies with V. minor and R. serpentina showed that RsPiNMT and VmPiNMT gene expression and biochemical activities were highest in younger leaf tissues. The assembly of at least 150 known N-methylated MIAs within members of the Apocynaceae family may have occurred as a result of the evolution of the γ-tocopherol-like N-methyltransferase family from γ-tocopherol methyltransferases.

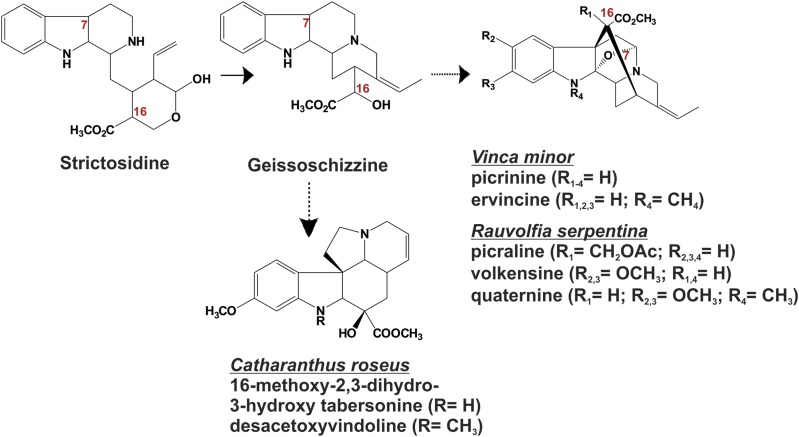

Monoterpenoid indole alkaloids (MIAs) are a large and structurally heterogeneous group of specialized natural products generally derived from the condensation of tryptamine and the monoterpene iridoid secologanin to yield the central precursor strictosidine (Fig. 1; Salim and De Luca, 2013). The versatility of the strictosidine backbone is revealed by the strictosidine β-glucosidase-mediated generation of aglycone intermediates that undergo multiple biochemical rearrangements and substitutions involving cyclases, hydroxylases, oxidoreductases, glycosyltransferases, acyltransferases, methyltransferases, and a few other selected reactions to yield several thousand biologically active MIAs that have been described in the phytochemical literature (Buckingham et al., 2010). MIAs typically occur in the Apocynaceae, Loganiaceae, and Rubiaceae families of plants that have been rich sources of disease-curing medicines. Drugs from Rauvolfia serpentina have been used in treatment of hypertension (ajmalicine) and for diagnostic analyses (ajmaline), while powerful anticancer drugs such as camptothecin from Camptotheca acuminata and vinblastine/vincristine from Catharanthus roseus continue to be harvested from individual plant species.

Figure 1.

The conversion of strictosidine to various N-methylated MIAs in C. roseus, R. serpentina, and V. minor involves members of a newly discovered family of γ-TLMT enzymes. The reactions yielding ervincine and desacetoxyvindoline are catalyzed by PiNMT and DhtNMT. The desacetoxyvindoline reaction product of the DhtNMT reaction is then converted to vindoline by desacetoxyvindoline 4-hydroxylase and deacetylvindoline acetyltransferase. Solid arrows represent single enzymatic steps, while dotted arrows represent multiple enzymatic steps.

In recent years there has been significant progress in identifying new methyltransferase genes and biochemically characterizing their involvement in MIA biosynthesis, with a special emphasis on identifying early and late biochemical steps in vindoline biosynthesis (Salim and De Luca, 2013; Facchini and De Luca, 2008). Loganic acid O-methyltransferase was cloned based on its amino acid sequence similarity to salicylic acid O-methyltransferase, and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme confirmed its role in O-methylation of the carboxyl group of loganic acid in the second-to-last step in secologanin biosynthesis (Murata et al., 2008). The 16-hydroxytabersonine O-methyltransferase involved in vindoline biosynthesis was biochemically purified, and the gene was cloned and its recombinant gene product was functionally characterized to identify the fifth-to-last step in vindoline biosynthesis (Levac et al., 2008).

Most recently a new class of methyltransferases, phylogenetically related to γ-tocopherol C-methyltransferases, was identified and functionally characterized as 2,3-dihydrotabersonine N-methyltransferase (Cr2270; CrDhtNMT; Liscombe et al., 2010; Supplemental Table S1; Fig. 1). Prior to the discovery of this novel biochemical function, CrDhtNMT would have been categorized as a γ-tocopherol C-methyltransferase, and this gave rise to the naming of members of this class of enzymes as γ-tocopherol-like methyltransferases (γ-TLMTs; Liscombe et al., 2010). Additional in planta studies using virus-induced gene silencing to decrease expression of CrDhtNMT suppressed vindoline accumulation in affected leaves in favor of a novel MIA showing the appropriate mass of 16-methoxy-2,3-dihydro-3-hydroxytabersonine (Liscombe and O'Connor, 2011) and made a strong case for the involvement of this gene in the third-to-last step in vindoline and vindorosine biosynthesis. The biochemical localization of CrDhtNMT to chloroplast thylakoids (Dethier and De Luca, 1993) contrasts with the chloroplast envelope localization of tocopherol C-methyltransferases involved in vitamin E biosynthesis (Joyard et al., 2009). Also, the CrDhtNMT protein may lack a putative chloroplast transit peptide (Liscombe et al., 2010), raising important questions about the mobilization of CrDhtNMT gene product to this organelle.

While several hundred N-methylated MIAs that have been described in the phytochemical literature (Buckingham et al., 2010), only CrDhtNMT that catalyzes N-methylation of 3,2-dihydro-3-hydroxytabersonine in the vindoline pathway has been characterized at the biochemical and molecular level. This study investigates other γ-TLMTs that may be responsible for similar N-methylations of MIAs in other producing plant species. For example, picrinine together with a number of picrinine derivatives (picraline, volkensine, and quaternine; Fig. 1) were identified in Rauvolfia volkensii (Akinloye and Court, 1980a) and in Rauvolfia oreogiton (Akinloye and Court, 1980b). Picrinine has also been identified in Vinca minor (Grossmann et al., 1973) and in Vinca herbacea (Boga et al., 2011), while its N-methyl derivative, ervincine, occurs in Vinca erecta (Rakhimov et al., 1967). Candidate γ-TLMT genes were identified by searching annotated EST databases (www.phytometasyn.ca; Facchini et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2013) of C. roseus, V. minor, and R. serpentina for a number of cDNAs that encode putative γ-TLMTs related to CrDhtNMT. We also report the molecular cloning and functional characterization of two novel candidate γ-TLMTs isolated from R. serpentina (RsPiNMT) and V. minor VmPiNMT), respectively, that N-methylate picrinine to generate ervincine (Fig. 1).

RESULTS

Mining of the V. minor, R. serpentina, and C. roseus Databases Suggests the Presence of a γ-TLMT Gene Family among Members of the Apocynaceae

RNA was extracted from young leaves of C. roseus and V. minor or from roots of R. serpentina, and samples were processed for combined 454 sequencing and annotation (www.phytometasyn.ca; Facchini et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2013). Mining of each annotated database for γ-TLMTs related to CrDhtNMT produced nine candidate genes that could be investigated for their possible roles as MIA N-methyltransferases. A neighbor-joining phylogeny using a class II methyltransferase (Cr2551; Liscombe et al., 2010) as an outgroup member was constructed together with the nine γ-TLMTs (Cr91, Cr706, VmPiNMT, Vm265, Vm2409, Rs820, Rs1755, RsPiNMT, and Rs8609; Supplemental Table S1), as well as with a previously identified but functionally uncharacterized Catharanthus γ-TLMTs (Cr7756; Liscombe et al., 2010) and with known tocopherol methyltransferases (AtGTMT, HaGTMT, BnGTMT, and Cr1196; Supplemental Fig. S1; Supplemental Table S1). The phylogeny was tested using the UPGMA (Sneath and Sokal, 1973; Supplemental Fig. S1A) and Maximum Parsimony (Felsenstein, 1985; Supplemental Fig. S1B) methods, and bootstrap values greater than 75 were identified. The two methods identify a γ-TLMT gene family distinct from that of tocopherol C-methyltransferases within members of the Apocynaceae family, and the phylogeny based on the UPGMA tree appears to sort methyltransferases according to their biochemical activities, clearly separating PiNMTs from other γ-TLMTs and from tocopherol methyltransferases. While the Maximum Parsimony method clusters all γ-TLMTs together, and in a distinct clade from γ-tocopherol C-methyltransferases, it did not resolve PiNMTs from other γ-TLMTs. The added resolution of the UPGMA method is supported in this study and in ongoing studies that remain to be published with other γ-TLMTs where the biochemical function of individual genes is being elucidated.

ClustalW pairwise sequence alignments using the γ-TLMT nucleotide sequences showed that one 1094 bp candidate Cr91 (365 cluster members; KF896244) shared 99% sequence identity over the open reading frame with the published 16-methoxy-2,3-dihydrotabersonine N-methyltransferase (Cr2270, CrDhtNMT; HM584929) gene isolated from C. roseus (cv Little Bright Eyes; Liscombe et al., 2010). The predicted open reading frame of Cr91 consists of 870 bp encoding a protein of Mr = 32 kD, a putative pI = 6, and a single nucleotide difference predicted to result in a substitution mutation (K145 for E145), when compared with the published CrDhtNMT sequence. We therefore annotated Cr91 as CrDhtNMT and decided to clone this gene to conduct comparative substrate specificity studies to those of VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT. Other uncharacterized γ-TLMT-like genes (Cr2551 [HM584930], Cr7756; Liscombe et al., 2010) were not represented in this database. However, Cr7756, which was identified from a C. roseus root EST database (Liscombe et al., 2010), also was present in a previously described C. roseus root EST database (KF934425; Murata et al., 2006). The other Catharanthus γ-TLMT from our pyrosequencing database, Cr706 (KC708453), is not represented in the medicinal plant genomic resource database (medicinalplantgenomics.msu.edu).

ClustalW pairwise amino acid sequence alignment (Supplemental Fig. S1C) of VmPiNMT (Vm130, 276 cluster members; KC708450) and RsPiNMT (Rs8692, 339 cluster members; KC708448) revealed that they shared 84% amino acid sequence identity (Supplemental Fig. S1D) and 92% sequence similarity with each other. Remarkably, the uncharacterized Cr7756 γ-TLMT (Liscombe et al., 2010) appears to be closely related to R. serpentina RsPiNMT and V. minor VmPiNMT since it shares 79% and 88% amino acid sequence identity to them. In contrast, VmPiNMT, RsPiNMT, and Cr7756 only shared 72%, 71%, and 72% amino acid sequence identity to CrDhT (Supplemental Fig. S1D). This raised the possibility that the transcripts might encode proteins with alternative MIA substrate specificities to those of CrDhT.

R. serpentina and V. minor γ-TLMTs Are PiNMTs

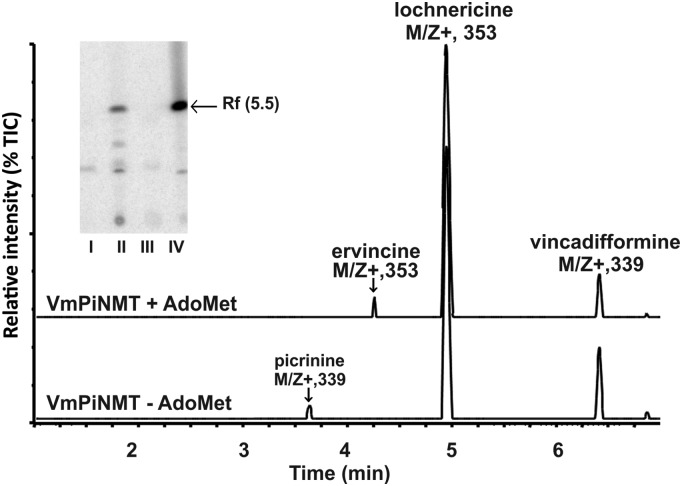

The nine candidate γ-TLMTs were cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. To identify potential substrates for any of the recombinant γ-TLMT enzymes, MIAs were obtained from C. roseus, V. minor, R. serpentina, Amsonia hubrichtii, and Tabernaemontana elegans. Only VmTLMT and RsTLMT generated novel radioactive reaction products when assayed in the presence of A. hubrichtii MIAs. This led to the selection of these two candidate genes for further analysis. Recombinant VmPiNMT (Fig. 2, inset, compare lanes I [empty vector control] and II [recombinant VmPiNMT]) and RsPiNMT (Fig. 2, inset, compare lanes III [empty vector control] and IV [recombinant RsPiNMT]) incubated with S-adenosyl-l-[methyl-14C]-Met ([14CH3]-AdoMet) methyl donor and Amsonia extracts converted the unknown MIA into a 14CH3-labeled product with a Rf of 5.5. When enzyme assays using nonradioactive AdoMet, MIAs from A. hubrichtii, and recombinant VmPiNMT were repeated on a larger scale to produce sufficient reaction product for ultraperformance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) analysis, a methylated product (possibly ervincine) eluting at 4.25 min (Fig. 2, VmPiNMT + AdoMet) with the expected mass (m/z+ 353) was detected coincident with the loss of an MIA (possibly picrinine) eluting at 3.6 min (m/z+ 339), while enzyme assays lacking AdoMet showed no methylation of the 3.6 min peak (Fig. 2, VmPiNMT − AdoMet). The mass and absorption spectra of the original MIA (Rt 3.6) and novel (Rt 4.25) methylated MIA peaks suggested that Amsonia surface exudates contain picrinine (based on absorption spectrum and mass analysis) that was converted by these recombinant enzymes to ervincine (Fig. 1). This detection of picrinine in A. hubrichtii extracts is supported by previous phytochemical analyses that have identified its presence in the related species Amsonia sinensis (Liu et al., 1991).

Figure 2.

Recombinant VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT enzymes catalyze methyltransferase reactions in the presence of appropriate MIA substrates. MIAs obtained from leaf surfaces of A. hubrichtii were incubated with recombinant VmPiNMT or RsPiNMT enzymes, MIA extracts, and [14CH3]-AdoMet as methyl donor. MIA reaction products were submitted to TLC and visualized by autoradiography (inset; lane I, empty pET30b vector; lane II, rVmPiNMT; lane III, empty pET30b vector; lane IV, rRsPiNMT). Larger scale enzyme assays using rVmPiNMT were then repeated with nonradioactive AdoMet together with larger amounts of A. hubrichtii leaf surface MIAs to determine the MIA substrate being N-methylated as determined by UPLC-MS. Enzyme assays conducted in the presence of VmPiNMT and only Amsonia MIA extract (minus AdoMet) displayed one minor picrinine peak (Rt 3.62 min, m/z+ 339) corresponding to picrinine, together with the major Amsonia MIAs lochnericine (Rt 4.9 min, m/z+ 353) and vincadifformine (Rt 6.41, m/z+ 339). However, addition of AdoMet to this assay converted the minor picrinine peak (Rt 3.62 min, m/z+ 339) into ervincine (Rt 4.43 min, m/z+ 353).

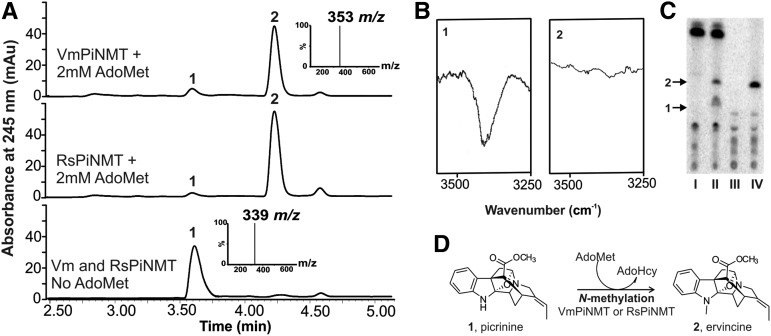

Larger scale assays with recombinant VmPiNMT (Fig. 3A, top) or RsPiNMT (Fig. 3A, middle) enzymes incubated with pure picrinine and with AdoMet clearly converted picrinine (Rt = 3.6 min, m/z+ 339) to ervincine (Rt = 4.25 min, m/z+ 353), compared with enzyme assays without AdoMet that produced no reaction product (Fig. 3A, bottom). Infrared spectroscopy showed that the indole N-H stretching observed between 3250 and 3500 cm−1 of picrinine (Fig. 3B, 1) is eliminated in the reaction product (Fig. 3B, 2), confirming that the reaction generates ervincine.

Figure 3.

Recombinant VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT catalyze the indole N-methylation of picrinine. UPLC-MS chromatograms show that recombinant VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT will convert picrinine (1: Rt 3.60, m/z+ 339) into ervincine (2: Rt 4.25, m/z+ 353) in the presence of 2 mm AdoMet (A) compared with enzyme assays without AdoMet or those conducted with the empty pET30b vector. The infrared spectrum of picrinine standard (B, 1) shows clear N-H stretching between 3250 and 3500 cm−1 corresponding to the N-H stretch of a secondary amine. The absence of this stretch with the ervincine reaction product (B, 2) confirms that the addition of the methyl group takes place on the indole N. The presence of PiNMT enzyme activity in leaves of V. minor or R. serpentina was shown by performing PiNMT enzyme assays containing crude leaf protein extracts, picrinine substrate, and [14CH3]-AdoMet (C). Autoradiograms of reaction products separated by TLC show reaction products made by V. minor and R. serpentina leaf protein extracts assayed in the absence (lanes I and III) and presence (lanes II and IV) of picrinine. The reaction scheme for the enzymatic conversion of picrinine to ervincine is shown (D).

More detailed substrate specificity studies using a number of MIA substrates (Supplemental Tables S2–S4) showed that while both recombinant VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT preferred picrinine as their best MIA substrate, they also accepted to a minor extent the structurally related 21-hydroxycyclolochnericine and norajmaline (Supplemental Table S3) that feature a cyclic ether ring or an ajmalan backbone in their terpene moieties. Among the MIAs that have been described, the akuammilan class of MIAs are produced by cyclization of C-16 to C-7 (such as picrinine), while the akuammidan class of MIAs are produced by cyclization of C-16 to C-5 (such as perivine; Szabó, 2008; Exkermann and Gaich, 2013). Since neither recombinant enzyme was able to use perivine as a substrate (Supplemental Tables S2 and S3), there may be separate γ-TLMTs that are responsible for producing N-methylated derivatives of the akuammidan class of MIAs that have been characterized in the phytochemical literature. The recombinant His-tagged RsPiNMT and VmPiNMT were purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatography (Supplemental Fig. S2) and were submitted to kinetic analysis. Substrate saturation kinetics for both enzymes produced Kms of 21.0 ± 3.0 μm and 20.1 ± 4.2 μm for picrinine and 9.3 ± 1.1 μm and 15.8 ± 2.6 μm for AdoMet, for RsPiNMT and VmPiNMT, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S3). The Km, Vmax, and Kcat/Km values for both recombinant enzymes were very similar for their respective substrates as those obtained for CrDhT (Liscombe et al., 2010; Supplemental Fig. S3). To complete the basic biochemical characterizations of the two recombinant PiNMTs, their pH optima were determined to be 7.5 and 7.0, for RsPiNMT and VmPiNMT, respectively, and the temperature optimum was 22°C for both enzymes.

PiNMT Activity Is Detected in Leaf Protein Extracts from V. minor and R. serpentina

The PiNMT activities of both recombinant enzymes prompted us to test leaf protein extracts from R. serpentina and V. minor for the presence of PiNMT activities (Fig. 3C). Enzyme assays contained pure picrinine, [14CH3]-AdoMet, and crude leaf protein extracts from V. minor or from R. serpentina established the presence of in planta PiNMT activity. V. minor leaf protein extracts assayed in the absence of picrinine produced a major (Rf = 0.98) and several unknown minor radioactive products (with Rfs < 0.3; Fig. 3C, lane I), while in the presence of picrinine, two additional products (Rf, 0.55 and 0.45; Fig. 3C, lane II) could be seen. Assays with R. serpentina leaf protein extracts displayed similar minor radiolabeled products (with Rfs below 0.3) in the absence of picrinine (Fig. 3C, lane III), while a major product (Rf, 0.55) appeared in its presence (Fig. 3C, lane IV). These results indicate that while internal unidentified substrates are being methylated by methyltransferases in crude leaf protein extracts, both plants also contained N-methyltransferase activities capable of N-methylating picrinine.

Recombinant Cr91 Is an Authentic CrDhtNMT That Does Not Accept Picrinine as a Substrate

Early biochemical characterization of the native enzyme purified from C. roseus leaf chloroplasts identified 2,3-dihydrotabersonine and its 3-hydroxy derivative to be substrates for N-methylation (Dethier and De Luca, 1993). The recombinant enzyme (Liscombe et al., 2010) was shown to catalyze methylation of the indole nitrogen of 2,3-dihydrotabersonine, 2,3-dihydro-3-hydroxytabersonine, and its 16-methoxy derivative by proton and carbon NMR together with high-resolution mass spectrometry. In this study, recombinant Cr91 also catalyzed the turnover of the same MIAs (Licombe, 2010) as well as 2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-3-hydroxytabersonine (Supplemental Table S4), confirming it to be the same functionally active CrDhtNMT. However, this enzyme did not accept perivine, 21-hydroxycyclolochnericine, norajmaline, or numerous other MIAs that were tested (Supplemental Table S2).

VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT Enzyme Activities and Transcripts Are Enriched in Tissues Actively Synthesizing MIAs

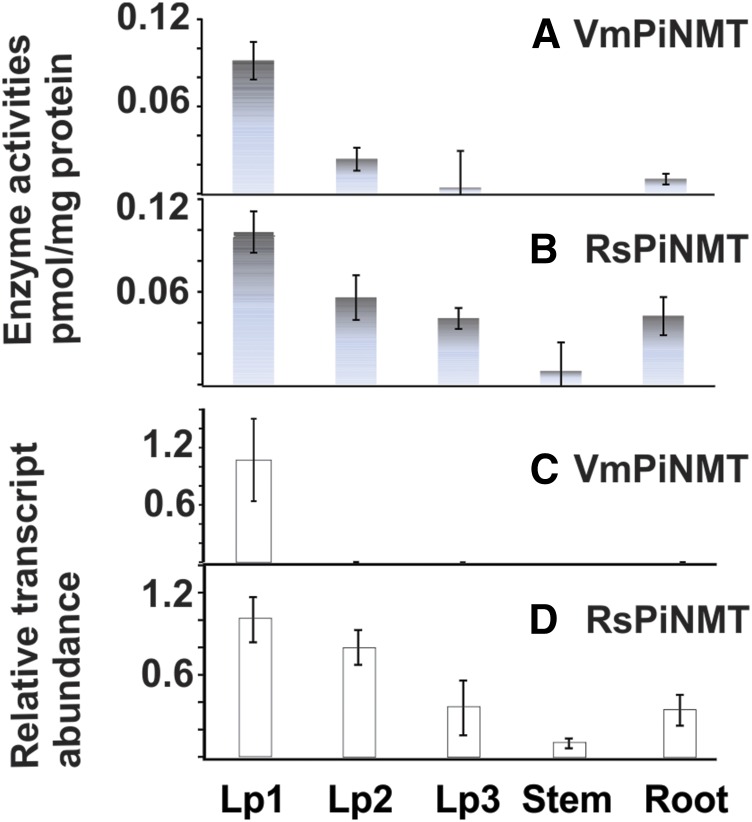

Crude whole tissue protein extracts were prepared from different organs of R. serpentina and V. minor as described in “Materials and Methods.” Extracts were desalted to remove small Mr molecules and were assayed for PiNMT activities using picrinine as substrate. VmPiNMT enzyme activities from V. minor first leaf pair were 4.5-, 22.5-, and 9-fold higher compared with those from second leaf pair, third leaf pair, and roots, respectively (Fig. 4A). The RsPiNMT activity in R. serpentina first leaf pair was 1.6-, 2.5-, 12.5-, and 2.5-fold higher than those from second leaf pair, third leaf pair, stems, and roots, respectively (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT enzyme activities are coordinated with gene expression in different tissues of V. minor and R. serpentina. A and B, Enzyme activity profiles for VmPiNMT (A) and RsPiNMT (B) in different tissues of each respective plant species. C and D, Relative transcript abundance profiles for VmPiNMT (C) and RsPiNMT (D) in different tissues of each respective plant species. Lp1 and Lp2 represents leaf pairs 1 and 2 next to the apical meristem, respectively. Each data point for enzyme activities and transcript abundance represents individual assays performed with three biological replicates ± sd.

The levels of VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT transcripts were determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) for the same tissue types analyzed for their respective N-methyltransferase biochemical activities. The VmPiNMT transcript levels were highest in first leaf pairs, while they were almost not detected in leaf pair 2, leaf pair 3, stems, or roots (Fig. 4C). In contrast, RsPiNMT transcript levels were detected in all organs, but their levels declined continuously with leaf age (Fig. 4D) and were lower in stem or in roots compared with leaf pair 1. These data show that while the enzyme activities found in different tissues (Fig. 4, A and B) followed very closely the transcript profiles observed (Fig. 4, C and D), each gene appeared to be regulated by different developmental and organ-specific controls in each plant species. In addition, the biological role(s) of VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT remains a mystery since MIA analyses of V. minor and R. serpentina tissues did not reveal the presence of picrinine or of its N-methylated derivative.

Only VmTLMT Possesses an N-Terminal Signal Peptide

Early investigations into the native CrDhtNMT enzyme employing Suc gradient fractionation suggested that it is associated with broken and intact chloroplasts and, more specifically, with thylakoid membranes (Dethier and De Luca, 1993). Release of the CrDhtNMT enzyme from thylakoids using detergents showed that it had an apparent Mr of 60,000 as determined by Suc density gradient centrifugation. Since the cloned CrDhtNMT has a putative subunit Mr of > 32,000 (Liscombe et al., 2010), together these data suggest that the functional enzyme may be a dimer (Dethier and De Luca, 1993). Since tocopherol methyltransferases are known to contain N-terminal plastid transit peptides, it was suggested that the published sequence for CrDhtNMT (Liscombe et al., 2010) might not be complete since it lacks this part of the sequence. While the Cr91-CrDhtNMT clone has a virtually identical predicted open reading frame as the CrDhtNMT, it has an additional 224 nucleotides upstream of the Kozak consensus sequence. These results suggest that CrDhtNMT may not possess an amino-terminal chloroplast transit peptide, although this needs to be further investigated. Remarkably, ClustalW multiple amino acid sequence alignment of CrDhtNMT, VmPiNMT, and RsPiNMT revealed highly similar methyltransferase domains absent of gaps (Supplemental Fig. S1C), while WolfP and TargetP 1.1 analysis of each protein predicted that only VmPiNMT contained a clearly identified 25 amino acid residue for a putative secretory transit peptide that may target this enzyme to extracellular spaces (Horton et al., 2007). The predicted open reading frame of VmPiNMT (969 bp) encodes a 35 kD protein (pI = 5.84) that when processed changes its Mr to 32 kD and reduces its apparent pI to 5.39. The RsPiNMT (873 bp) also encodes a 32 kD protein (apparent pI of 6.9).

DISCUSSION

A novel class of γ-TLMTs involved in the third-to-last step in vindoline biosynthesis was recently discovered (Liscombe et al., 2010; Liscombe and O’Connor, 2011), and its sequence was used in this study for large-scale transcriptome analysis of several MIA-producing plant species (www.phytometasyn.ca; Facchini et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2013). This study identifies nine new γ-TLMTs (Supplemental Fig. S1) and reports the biochemical function of a second member of this emerging family that is involved in the N-methylation of picrinine in V. minor (VmPiNMT) and R. serpentina (RsPiNMT). In addition, the evolution of different γ-TLMTs with different N-methylation substrate specificities may have led to the biosynthesis of at least 150 known MIAs (Buckingham et al., 2010) that have been discovered by phytochemists and that could be responsible for taxonomical clustering of indole N-methylated MIAs within the Apocynaceae.

The discovery of VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT was in part based on an interesting strategy for identifying the biochemical functions of different members of the γ-TLMT class of enzymes by harvesting potential MIA substrates from the leaf surfaces of plants that accumulate them and using them for biochemical activity testing (Roepke et al., 2010; Fig. 2). The method depends on sufficient amounts of substrate being available in the extract for conversion into product that can be detected in radioactive methyltransferase assays, followed by larger scale detection of products by UPLC-MS (Fig. 2). The use of radioactive assays (Fig. 2, inset) was essential for preliminary screening of MIA metabolites from leaf surface extracts, and this led to the identification of the minor MIA picrinine that acts as N-methyl acceptor (Fig. 2). While it was fortuitous that picrinine was commercially available for biochemical verification of VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT function, this methyl acceptor could have been purified from the source tissue for subsequent use in more detailed enzyme characterization of the recombinant proteins. This strategy to identify gene function is particularly useful in nonmodel plants systems, like R. serpentina and V. minor, where transient or stable gene knockdown methodologies have not been developed, or where these gene knockdown strategies do not yield clear target molecules because they may be unstable or they may be redirected to alternative pathways.

Substrate specificity studies showed that VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT N-methylated picrinine and to a much lower extent than 21-cyclolochnericine and norajmaline (Supplemental Table S3); they did not N-methylate tabersonine-related substrates that were accepted by recombinant CrDhtNMT (Supplemental Tables S2 and S4), and they were unable to use numerous other MIAs that were tested (Supplemental Table S2). Similarly, CrDhtNMT did not N-methylate picrinine, 21-cyclolochnericine, or norajmaline (Supplemental Table S4).

Previous studies with Catharanthus CrDhtNMT have suggested that this enzyme is associated with chloroplast membranes, and experiments with the detergent-solubilized enzyme established that it behaves as a 60 kD dimer (Dethier and De Luca, 1993) and as an undefined larger Mr aggregate in the absence of detergent. The lack of a transit peptide in CrDhtNMT raises questions about the mechanism involved to mobilize this enzyme to the chloroplast compartment. In contrast, VmPiNMT does have a putative secretory transit peptide that raises questions about its secretory role that can only be defined by detailed biochemical and cell biology localization studies.

The recombinant RsPiNMT and VmPiNMT enzymes (Supplemental Fig. S3) have very similar properties to those of CrDhtNMT (Liscombe et al., 2010) in terms of their similar Km, Vmax, and Kcat/Km values for their respective substrates. The inability of either RsPiNMT or VmPiNMT to N-methylate perivine or other MIAs provides support that other substrate-specific γ-TLMT family members may be involved in the biosynthesis of some of the 150 known N-methylated MIAs (Buckingham et al., 2010). While RsPiNMT did convert norajmaline to ajmaline, we do suspect that a separate γ-TLMT is likely to be responsible for the biosynthesis of ajmaline. While picrinine and its N-methylated derivative were not detected in our tested V. minor or R. serpentina plants, it was previously detected in V. minor (Grossmann et al., 1973; Buckingham et al., 2010) and in V. herbacea (Boga et al., 2011), whereas ervincine was also detected in V. erecta (Rakhimov et al., 1967; Liu et al., 1991; Fig. 1). In addition, picrinine, picraline, volkensine, and quaternine (Fig. 1) accumulate in R. volkensii (Akinloye and Court, 1980a) and R. oreogiton (Akinloye and Court, 1980b). Members of the genus Alstonia produce a range of picrinine (Hai et al., 2008) and picraline (Arai et al., 2010) derivatives that include powerful N-methylated drug candidates that inhibit the Na+-Glc cotransporter involved in the reabsorption of Glc in human kidneys. In addition, picrinine from Alstonia scholaris (Chatterjee et al., 1965) has been documented to have powerful antitussive, antiasthmatic, and expectorant properties (Shang et al., 2010). We conclude that the many N-methylated derivatives of picrinine found in nature are likely to involve the new PiNMT genes described in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Catharanthus roseus (cv Little Delicata), Rauvolfia serpentina, and Vinca minor plants were grown in a greenhouse under a long-day photoperiod at 28°C. Young leaves (<1.5 cm in length), whole root, and first leaf pair, respectively, were harvested for isolation of total RNA and for use in next generation 454 Roche pyrosequencing. Other tissues to be used for other experiments were also harvested and extracted in the same manner.

MIA Standards

Catharanthine (1), 16-hydroxytabersonine (2), 16-methoxytabersonine (3), 2,3-dihydrotabersonine (4), 3-hydroxytabersonine (5), desacetoxyvindoline (6), deacetylvindoline (7), vindoline (8), vinblastine (9), vincristine (10), 6,7-dihydro-3-hydroxy-tabersonine (11), 2,3-dihydro-3-hydroxy-N-methyltabersonine (12), 16,18-dibromo-3-hydroxytabersonine (13), horhammericine (14), lochnericine (15), and 21-hydroxycyclolochrericine (16) were from our MIA collection that has been assembled since 1984 through isolation from natural sources (1, 7, 8), receipt as gifts (9, 10, 14, 15, 16), through chemical synthesis from tabersonine (Balsevich et al., 1996; De Luca et al., 1986), or through biochemical (Qu et al., 2015) synthesis (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13).

Vincadifformine was extracted and purified from Amsonia hubrichtii. A chloroform extract was obtained from 768 g of young A. hubrichtii leaves and stems by immersion in chloroform (4 L) over a 3 h period at room temperature with periodic shaking. After the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, the residue was suspended in 200 mL of water:methanol (80:20), acidified to pH 2 with 10% (v/v) H2SO4 and subsequently washed several times with ethyl acetate. The resultant aqueous phase was then basified to pH 12 with 10 n NaOH and subsequently washed several times with ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate phase was separated from the aqueous phase and evaporated in vacuo, yielding 1.6 g of total alkaloids. Eight hundred milligrams of the residue was subjected to silica gel column chromatography with isocratic elution of chloroform:methanol (9:1), and the first yellow colored fractions were collected. Twelve microliters of the colored fractions was evaporated using a SPD SpeedVac (Thermo Savant), yielding 180 mg of hydrophobic alkaloids that contained approximately 60% vincadifformine. The residue was subjected to preparative TLC (TLC Silica gel 60 F254; EMD) with hexane:ethyl acetate (8:2) as the eluent. The bands that developed at Rf 0.49 were scraped and eluted with methanol. The removal of the methanol produced approximately 10 mg of a white crystal powder. The NMR spectrum of this powder was identical to that of a reference sample of vincadifformine (Kalaus et al., 1993). 1H NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker Avance AV 600 Digital NMR spectrometer (Bruker) with a 14.1 Tesla Ultrashield Plus magnet. 1H NMR spectra (in CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ (ppm): 0.58 (3H, m; C20-CH2CH3), 3.2 (3H, s; COOCH3), 6.8 to 7.3 (4H, m; aromatic H), 8.9 (1H, br s; indole NH).

Ajmaline and vincamine were purchased from www.extrasynthese.com and www.caymanchem.com, respectively. Norajmaline was produced from ajmaline by fermentation in the presence of Streptomyces platensis. Norajmaline was then purified by TLC. Picrinine and perivine standards were purchased from www.avachem.com. Tabersonine standard was purchased in 1986 from Omnichem NV. Purity of all compounds was > 98% as determined by UPLC-MS analysis.

MIA Isolation from Leaf Surfaces

Leaves from A. hubrichtii, C. roseus, V. minor, and R. serpentina were submerged in chloroform in Erlenmeyer flasks and shaken at 100 RPM for 2 h to extract surface MIAs from each plant species. The chloroform was decanted into a round bottom flask, and extracts were taken to dryness by flash evaporation. The residue was dissolved in methanol and water (85:15 water:methanol) acidified to pH 3 with 10% (v/v) H2SO4. Contaminating small molecules were extracted into ethyl acetate that was discarded, and 10 n NaOH was added to the aqueous phase, pH 12. MIAs were extracted into ethyl acetate, and this crude MIA fraction was taken to dryness by flash evaporation, dissolved in methanol, and stored at −20°C until use for enzyme assays.

Total RNA Isolation

Plant tissues (0.2 g) were harvested from the greenhouse and homogenized in a mortar and pestle with liquid nitrogen to produce a fine powder. Total RNA was extracted from powdered homogenate using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The final pellet was washed three times with 75% (v/v) ethanol to remove salts and stored in 100% ethanol at −80°C until needed.

Database Mining and Identification of γ-TLMTs

The database assembly and transcript annotations from A. hubrichtii, C. roseus, R. serpentina, Tabernaemontana elegans, V. minor, and Lonicera japonica transcriptomes (Facchini et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2013), found at www.phytometasyn.ca, were used to search for γ-TLMTs. The nucleotide sequences of the CrDhtNMT (HM584929; Liscombe et al., 2010) and AtγTMT (AF104220) open reading frames were used to independently query all PhytoMetaSyn databases (BLASTn Portal and an E value threshold cutoff of 10).

This search revealed hits of significance (E value < e-10) in the C. roseus, V. minor, and R. serpentina databases, whereas the T. elegans, A. hubrichtii, and L. japonica databases do not contain contigs of significant homology. BLASTn analysis using the same N-methyltransferase nucleotide query to search all PhytoMetaSyn assemblies revealed no transcripts of significant similarity to the published CrDhtNMT outside of the Vinceae tribe of Apocynaceae, whereas BLASTn searches of this portal using the Arabidopsis γ-tocopherol C-methyltransferase (γTMT) nucleotide sequence as query revealed the expected γTMT homologs in all databases.

Hits annotated as γ-tocopherol C-methyltransferases were excluded from further analysis.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Amino Acid Alignment of Tocopherol and Tocopherol-Like Methyltransferases

Tocopherol and tocopherol-like peptide amino acid sequences (Supplemental Table S1) were copied into the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6 application (MEGA6) integrated tool for phylogenetic analysis (Tamura et al., 2011, 2013), and peptide sequences were aligned using Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation (MuSCLE; Edgar, 2004) with the following constraints: Gap Penalties: Open = −2.9, Extend = 0, Hydrophobicity Multiplier = 1.2. Memory/Iterations: Max Memory in Mb = 4095, Max iterations = 50. Clustering Method UPGMB.

Phylogeny Construction

The evolutionary history was inferred with two different methods. Using the UPGMA method (Sneath and Sokal, 1973), the bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1000 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed (Felsenstein, 1985). Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 75% bootstrap replicates are collapsed. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown next to the branches (Felsenstein, 1985). The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method (Zuckerkandl and Pauling, 1965) and are in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. The analysis involved 13 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 275 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6 (Tamura et al., 2013). Using the Maximum Parsimony method, the bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1000 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed (Felsenstein, 1985). Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 75% bootstrap replicates are collapsed. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown next to the branches (Felsenstein, 1985). The MP tree was obtained using the Subtree-Pruning-Regrafting algorithm (Nei and Kumar, 2000) with search level 1, in which the initial trees were obtained by the random addition of sequences (10 replicates). The analysis involved 13 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 275 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6 (Tamura et al., 2013).

Molecular Cloning of N-Methyltransferases from C. roseus, V. minor, and R. serpentina

Total RNA from each species was obtained as described in earlier sections, and cDNA synthesis was performed using AMV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega). Full-length cDNA sequences for CrDhtNMT (HM584929), Vm130 (VmPiNMT; accession no. KC708450), and Rs8692 (RsPiNMT; accession no. KC708448) were cloned using PCR primers (DhtNMT_Fw 5′ TTCATATGGAAGAGAAGCAGGAG 3′, DhtNMT_Rv 5′ TTGCGGCCGCATATTGATTTTCGTCCGTAAC 3′; VmPiNMT_Fw 5′ TTCATATGTACACTTGTTCAATTATAATATATAT 3′, VmPiNMT_Rv 5′ TTGCGGCCGCATTTAGATTTGCGGCATGTAAC 3′; and RsPiNMT_Fw 5′ TTCATATGGCAGAGAAGCAGCAGGC 3′, RsPiNMT_Rv 5′ TTGCGGCCGCATTTTGATTTCCTGCATGTAATTGCAAC 3′). Note the presence of 5′ NdeI and 3′ NotI restriction sites. These restriction sites were incorporated to facilitate directional cloning into the pET30b (Invitrogen) Escherichia coli expression vector.

Production and Purification of the Recombinant VmPiNMT and RsPiNMT

E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL (Stratagene) harboring pET30b/CrDhT, pET30b/VmPiNMT, or pET30b/RsPiNMT were cultivated in 1 L of Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 50 mg L−1 kanamycin at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) to an OD600 of 0.6 and then induced with isopropylthio-β-galactoside (1 mm final concentration) at 20°C with shaking (125 rpm). After 9 h of growth at 20°C, cells were collected by centrifugation (3000g) for 15 min at 4°C. Pelleted cells were resuspended in buffer A (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.7, 300 mm NaCl, 10% [v/v] glycerol, 14 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mm imidazole) and lysed by sonication. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (3000g) for 25 min at 4°C. The supernatant was submitted to a Ni-NTA Agarose (Qiagen) column chromatography (previously equilibrated in buffer A), which was then washed in a stepwise manner with buffer A containing increasing concentration (20, 50, 100, and 250 mm) of imidazole. Recombinant RsPiNMT was purified by elution with 20 mm imidazole, while recombinant VmPiNMT was purified by elution with 100 mm imidazole elution (Supplemental Fig. S2). To remove the imidazole, PiNMTs were desalted using a PD Spin Trap G-25 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.7, 14 mm β-mercaptoethanol.

Extraction of Enzyme Activities from C. roseus, V. minor, and R. serpentina Leaves

First leaf pairs (5 g) were harvested from C. roseus, V. minor, and R. serpentina to be harvested and homogenized in a cooled mortar and pestle with 15 mL of ice-cold 100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.7, 14 mm mercaptoethanol. Leaf homogenates were then filtered through cheese cloth into a 15 mL conical tube, and filtrates were centrifuged at 1000g to remove large debris. The resulting supernatant was desalted by Sephadex G25 chromatography and used directly for enzyme assays.

Protein Determination

The levels of protein were determined (Bradford, 1976) using the protein assay dye reagent (Bio-Rad) and bovine serum albumin as standard.

NMT Enzyme Assays

NMT activities were determined using a radioactive enzyme assay (150 µL) containing protein (recombinant or from plant extracts), 2.5 nCi S-[14CH3]-AdoMet (specific activity 58 mCi/mmol; GE Healthcare Canada), and 5 µg substrate (2,3-dihydro-3-hydroxytabersonine for DhtNMT, or picrinine for the two PiNMTs), 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.7, 14 mm mercaptoethanol). Enzyme assays were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Assays were stopped by adding 10% (v/v) 10 n NaOH, and reaction products were extracted with 500 µL of ethyl acetate. A 50 µL aliquot of the reaction products was used for quantification by scintillation (Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter), while the remainder was dried, dissolved in 10 µL of methanol, and submitted to TLC (Silica Gel 60 F254; EMD Millipore) using solvent system chloroform:methanol (9:1). Radioactive reaction products were visualized and quantified by exposing the TLC to a storage phosphor screen (GE Healthcare) for at least 16 h, and emissions from the phosphor screen were detected using a Phosphorimager FLA-3000 (Fujifile). The standard nonradioactive enzyme assay (200 µL) contained crude desalted recombinant enzyme, 2 mm AdoMet, 5 µg of substrate, and enzyme assay buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.7, 14 mm mercaptoethanol). Enzyme assays were incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Assays were stopped by adding 10% (v/v) 10 n NaOH, and reaction products were extracted to 500 µL of ethyl acetate. Organic phases of three replicate assays were combined into a single 2 mL tube and taken to dryness using a SAVANT Speedvac (Thermo Scientific). Dried alkaloid products were resuspended in 200 µL of methanol and filtered through a 0.22 µm PALL filter (VWR Canada).

Reaction products were analyzed by ultra-HPLC with diode array detections and mass spectrometry UPLC-MS (Waters) where MIAs were separated using an Aquity UPLC BEH C18 column with a particle size of 1.7 μm and column dimensions of 1.0 × 50 mm. Samples were maintained at 4°C, and 5 μL injections were made into the column. The solvent systems for MIA analyses were as follows: solvent A, methanol:acetonitrile:5 mm ammonium acetate at 6:14:80; solvent B, methanol:acetonitrile:5 mm ammonium acetate at 25:65:10. The following linear elution gradient was used: 0 to 0.5 min 99% A, 1% B at 0.3 mL/min; 0.5 to 0.6 min 99% A, 1% B at 0.4 mL/min; 0.6 to 7.0 min 1% A, 99% B at 0.4 mL/min; 7.0 to 8.0 min 1% A, 99% B at 0.4 mL/min; 8.0 to 8.3 min 99% A, 1% B at 0.4 mL/min; 8.3 to 8.5 min 99% A, 1% B at 0.3 mL/min; and 8.5 to 10.0 min 99% A, 1% B at 0.3 mL/min. The mass spectrometer was operated with a capillary voltage of 2.5 kV, cone voltage of 34 V, cone gas flow of 2 L/h, desolvation gas flow of 460 L/h, desolvation temperature of 400°C, and a source temperature of 150°C.

Substrate Specificity Assays

Desalted crude recombinant protein extracts (rPiNMT, rDhtNMT) were used to assay pure alkaloid substrates from our collection to identify small molecules accepted by each N-methyltransferase. Initial screening used the standard radioactive enzyme assay with an incubation time of 3 h. Any substrates that yielded greater than 3× background radioactive counts were repeated using nonradioactive assay conditions in batches of three replicates. Replicates of nonradioactive enzyme assay products were extracted to organic, pooled, dried, and prepared for UPLC-MS analysis as described previously.

PiNMT Kinetic Analysis—Saturation Curves

PiNMT assays contained 700 ng of affinity purified protein (Supplemental Fig. S2), 0.9 to 80 µm picrinine, 1.35 to 50 µm AdoMet (mixed with 0.006 µCi [14CH3]-AdoMet 56.3 mCi mmol−1 specific activity; Perkin-Elmer), in a total volume of 50 µL. Kinetic assays were performed under optimal conditions (30°C, buffer B), incubated for 15 min, and terminated with the addition of 15 µL of 10 m NaOH. The reaction product was extracted with 400 µL of ethyl acetate and centrifuged at 10,000g for 1 min. Finally, 200 µL of the organic phase was analyzed using a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter. For picrinine kinetics AdoMet was fixed at 100 µm (mixed with 0.014 µCi [14CH3]-AdoMet 56.3 mCi mmol−1 specific activity; Perkin-Elmer), and for AdoMet kinetics picrinine was fixed at 200 µm. Kinetic data were fitted by nonlinear regression and analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software).

qRT-PCR and PiNMT Enzyme Activities in Different Organs

Gene expression was monitored by qRT-PCR (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) using PCR primers flanking the stop codon such that the 3′ untranslated region of the transcript assists in increasing the specificity of the PCR reaction. The primer pairs Actin-F (5′-GGAGCTGAGAGATTCCGTTG-3′) and Actin-R (5′-GAATTCCTGCAGCTTCCATC-3′), CrDhtNMT-F (5′-CCTTACCCCATCAAGTCGAA-3′) and CrDhtNMT-R (5′-CCTTACCCCATCAAGTCGAA-3′), VmPiNMT-F (5′-TTCTCTCATGGCTTTGTTCT-3′) and VmPiNMT-R (5′-TTAACGAAATTTTTGGCATT 3′), and RsPiNMT-F (5′-ACATGCAGGAAATCCAAATA-3′) and RsPiNMT-R (5′-ATTCATCAAGAGCTCCACAC-3′) were used to generate 73 bp, 274 bp, and 302 bp length PCR products, respectively. The qRT-PCR reaction was carried out in a final 25 μL containing 200 nm each primer, 12 μL of iQ SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad), and 1 μL of cDNA (corresponding to approximately 286 ng of cDNA) using the following conditions: 95°C for 15 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 30 s using the CFX96 real-time SYBR system (Bio-Rad). Three biological replicates were collected for each C. roseus, R. serpentina, and V. minor tissue, and single qRT-PCR reactions were conducted for each biological replicate.

Individual organs (1.5 g) were harvested in triplicate from C. roseus, V. minor, and R. serpentina. Tissues were extracted and assayed for PiNMT activities as described above.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers KF896244 (Cr91); KC708453 (Cr706); KF934425 (Cr7756); KC708450 (Vm130 or VmPiNMT); KC708451 (Vm265); KC708452 (Vm2409); KC708445 (Rs820); KC708446 (Rs1755); KC708448 (Rs8692 or RsPiNMT); KC708447 (Rs8609).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Comparative phylogenetic and amino acid analyses of various tocopherol MTs and tocopherol-like NMTs.

Supplemental Figure S2. SDS-PAGE analysis of purified recombinant RsPiNMT and VmPiNMT.

Supplemental Figure S3. Substrate saturation curves and kinetics for purified, recombinant RsPiNMT and VmPiNMT.

Supplemental Table S1. Accession numbers of genes used for phylogeny analyses.

Supplemental Table S2. Some monoterpenoid indole alkaloid structures used of substrate specificity studies.

Supplemental Table S3. Substrate specificity analyses of recombinant RsPiNMT and VmPiNMT.

Supplemental Table S4. Substrate specificity analyses of recombinant CrDhtNMT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We recognize the skilled technical work of next-generation sequencing personnel at the McGill University-Genome Québec-Innovation Centre. We are grateful to Christoph Sensen, Mei Xiao, and Ye Zhang for their dedicated bioinformatic support and large-scale gene annotation efforts that helped in the identification of γ-TLMTs from the Phytometasyn Web site. We would like to thank the Mr. Lorne Fast, Curator of Collections, Niagara Parks Botanical Gardens and School of Horticulture, for provision of A. hubrichtii plants used in part of this study.

Glossary

- MIA

monoterpenoid indole alkaloid

- UPLC-MS

ultraperformance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

Footnotes

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Arai H, Hirasawa Y, Rahman A, Kusumawati I, Zaini NC, Sato S, Aoyama C, Takeo J, Morita H (2010) Alstiphyllanines E-H, picraline and ajmaline-type alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla inhibiting sodium glucose cotransporter. Bioorg Med Chem 18: 2152–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinloye BA, Court WE (1980a) Leaf alkaloids of Rauvolfia volkensii. Phytochemistry 19: 307–311 [Google Scholar]

- Akinloye BA, Court WE (1980b) Leaf alkaloids of Rauvolfia oreogiton. Phytochemistry 19: 2741–2745 [Google Scholar]

- Balsevich J, De Luca V, Kurz WGW (1986) Altered alkaloid pattern in dark grown seedlings of Catharanthus roseus. The isolation and characterization of 4-desacetoxyvindoline, a novel indole alkaloid and possible precursor of vindoline. Heterocycles 24: 2415–2420 [Google Scholar]

- Boga M, Kolak U, Topcu G, Bahadori F, Kartal M, Farnsworth NR (2011) Two new indole alkaloids from Vinca herbacea L. Phytochem Lett 4: 399–403 [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham J, Baggaley K, Roberts A, Szabo L, editors (2010) Dictionary of Alkaloids. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, Mukherjee B, Ray AB, Das B (1965) The alkaloid of the leaves of Alstonia scholaris R. Br. Tetrahedron Lett 41: 3633–3637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca V, Balsevich J, Tyler RT, Kurz WGW (1987) Characterization of a novel N-methyltransferase (NMT) from Catharanthus roseus plants: detection of NMT and other enzymes of the indole alkaloid biosynthetic pathway in different cell suspension culture systems. Plant Cell Rep 6: 458–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethier M, De Luca V (1993) Partial purification of an N-methyltransferase involved in vindoline biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus. Phytochemistry 32: 673–678 [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exkermann R, Gaich T (2013) The akuammiline alkaloids; origin and synthesis. Synthesis 45: 2813–2823 [Google Scholar]

- Facchini PJ, Bohlmann J, Covello PS, De Luca V, Mahadevan R, Page JE, Ro DK, Sensen CW, Storms R, Martin VJ (2012) Synthetic biosystems for the production of high-value plant metabolites. Trends Biotechnol 30: 127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchini PJ, De Luca V (2008) Opium poppy and Madagascar periwinkle: model non-model systems to investigate alkaloid biosynthesis in plants. Plant J 54: 763–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann E, Sevcovic P, Szasz K (1973) Picrinine in Vinca minor. Phytochemistry 12: 2058 [Google Scholar]

- Hai CX, Ya-Ping L, Tao F, Xiao-Dong L (2008) Picrinine-type alkaloids from the leaves of Alstonia scholaris. Chin J Nat Med 6: 20–22 [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, Nakai K (2007) WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res 35: W585–W587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyard J, Ferro M, Masselon C, Seigneurin-Berny D, Salvi D, Garin J, Rolland N (2009) Chloroplast proteomics and the compartmentation of plastidial isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways. Mol Plant 2: 1154–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaus G, Greiner I, Kajatar-Peredy M, Brlik J, Szabo L, Szantay C (1993) Synthesis of Vinca alkaloids and related compounds. A new synthetic pathway for preparing alkaloids and related compounds with Aspidosperma skeleton. Total syntheses of (+)-vincadifformine, (+)-tabersonine, and (+)-3-oxotabersonine. J Org Chem 58: 1434–1442 [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Murata J, Kim WS, De Luca V (2008) Application of carborundum abrasion for investigating the leaf epidermis: molecular cloning of Catharanthus roseus 16-hydroxytabersonine-16-O-methyltransferase. Plant J 53: 225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscombe DK, Usera AR, O’Connor SE (2010) Homolog of tocopherol C methyltransferases catalyzes N methylation in anticancer alkaloid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18793–18798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscombe DK, O’Connor SE (2011) A virus-induced gene silencing approach to understanding alkaloid metabolism in Catharanthus roseus. Phytochemistry 72: 1969–1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HM, Wu B, Zheng QT, Feng XZ (1991) New indole alkaloids from Amsonia sinensis. Planta Med 57: 566–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata J, Bienzle D, Brandle JE, Sensen CW, De Luca V (2006) Expressed sequence tags from Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus). FEBS Lett 580: 4501–4507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata J, Roepke J, Gordon H, De Luca V (2008) The leaf epidermome of Catharanthus roseus reveals its biochemical specialization. Plant Cell 20: 524–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Kumar S (2000) Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Easson MLAE, Froese J, Simionescu R, Hudlicky T, De Luca V (2015) Completion of the 7 step pathway from tabersonine to the anticancer drug precursor vindoline and its assembly in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 6224–6229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhimov DA, Malikov VM, Yunusov SY (1967) Isolation of kopsinilam and ervincine. Khimiya Prirodnykh Soedinenii 3: 354–355 [Google Scholar]

- Roepke J, Salim V, Wu M, Thamm AM, Murata J, Ploss K, Boland W, De Luca V (2010) Vinca drug components accumulate exclusively in leaf exudates of Madagascar periwinkle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 15287–15292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim V, De Luca V (2013) Towards complete elucidation of monoterpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis pathway: Catharanthus roseus as a pioneer system. Annals of Botanical Research 68: 1–38 [Google Scholar]

- Shang JH, Cai XH, Feng T, Zhao YL, Wang JK, Zhang LY, Yan M, Luo XD (2010) Pharmacological evaluation of Alstonia scholaris: anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. J Ethnopharmacol 129: 174–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath PHA, Sokal RR (1973) Numerical Taxonomy. Freeman, San Francisco [Google Scholar]

- Szabó LF. (2008) Rigorous biogenetic network for a group of indole alkaloids derived from strictosidine. Molecules 13: 1875–1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28: 2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30: 2725–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao M, Zhang Y, Chen X, Lee EJ, Barber CJ, Chakrabarty R, Desgagné-Penix I, Haslam TM, Kim YB, Liu E, et al. (2013) Transcriptome analysis based on next-generation sequencing of non-model plants producing specialized metabolites of biotechnological interest. J Biotechnol 166: 122–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L (1965) Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins. In Bryson V, Vogel HJ, Evolving Genes and Proteins. Academic Press, New York, pp 97–166 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.