A Cystathionine-β-Synthase like protein, exclusively expressed during Medicago-Rhizobium symbiosis, is required for infection thread propagation and bacterial endocytosis.

Abstract

The symbiosis between leguminous plants and soil rhizobia culminates in the formation of nitrogen-fixing organs called nodules that support plant growth. Two Medicago truncatula Tnt1-insertion mutants were identified that produced small nodules, which were unable to fix nitrogen effectively due to ineffective rhizobial colonization. The gene underlying this phenotype was found to encode a protein containing a putative membrane-localized domain of unknown function (DUF21) and a cystathionine-β-synthase domain. The cbs1 mutants had defective infection threads that were sometimes devoid of rhizobia and formed small nodules with greatly reduced numbers of symbiosomes. We studied the expression of the gene, designated M. truncatula Cystathionine-β-Synthase-like1 (MtCBS1), using a promoter-β-glucuronidase gene fusion, which revealed expression in infected root hair cells, developing nodules, and in the invasion zone of mature nodules. An MtCBS1-GFP fusion protein localized itself to the infection thread and symbiosomes. Nodulation factor-induced Ca2+ responses were observed in the cbs1 mutant, indicating that MtCBS1 acts downstream of nodulation factor signaling. MtCBS1 expression occurred exclusively during Medicago-rhizobium symbiosis. Induction of MtCBS1 expression during symbiosis was found to be dependent on Nodule Inception (NIN), a key transcription factor that controls both rhizobial infection and nodule organogenesis. Interestingly, the closest homolog of MtCBS1, MtCBS2, was specifically induced in mycorrhizal roots, suggesting common infection mechanisms in nodulation and mycorrhization. Related proteins in Arabidopsis have been implicated in cell wall maturation, suggesting a potential role for CBS1 in the formation of the infection thread wall.

Legumes can utilize atmospheric di-nitrogen for growth by virtue of symbiotic nitrogen fixation with rhizobia bacteria, which is central to sustainable agriculture (Peoples et al., 2009). To support symbiotic nitrogen fixation, legumes develop specialized organs called nodules, typically from root tissue. Nodule development is triggered by specific lipochitooligosaccharides called Nodulation (Nod) factors produced by rhizobia in response to flavonoids released from legume roots (Oldroyd, 2013). Nod factors are perceived by receptors on plant root hair cells, which leads to several responses, including plasma membrane depolarization, Ca2+ influx, and Ca2+ spiking, within minutes (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Wais et al., 2000; Messinese et al., 2007; Horváth et al., 2011). Within hours of Nod factor perception, large-scale reprogramming of plant gene expression occurs, which supports rhizobial infection and nodule development (Oldroyd, 2013). Infection begins with rhizobial attachment to the tip of growing root hair cells, which leads to asymmetric growth (curling) of the root hair cells and formation of a characteristic shepherd’s-crook structure that entraps rhizobia inside an infection focus. Rhizobia in this pocket divide and multiply to form a microcolony, while a plant pectate lyase digests the adjacent plant cell wall (Xie et al., 2012). This allows entry of rhizobia into the plant cell via a tubular invagination of the plasma membrane and cell wall called the infection thread (IT). IT initiation occurs about 10 to 20 h after root hair curling is complete (Fournier et al., 2015). The IT then grows toward the base of the root hair cell and guides the bacteria to the root cortex (Fournier et al., 2008; Murray, 2011; Oldroyd et al., 2011).

Genetic studies using the model legumes Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus have identified many plant genes that are required for bacterial recognition, nodulation, and nitrogen fixation. The Nod factor perception mutants nod factor perception (Mtnfp)/nod factor recognition (Ljnfr5) exhibit no physiological or morphological responses in root hair cells to inoculation with rhizobia, including lack of Nod factor-induced Ca2+ spiking (Ben Amor et al., 2003; Madsen et al., 2003; Arrighi et al., 2006). Other mutants, including Ljnfr1, Ljnucleoporin85 (Ljnup85), Ljnup133, Ljcastor, Ljpollux/does not make infections1, Ljnena, and Mtdmi2/symbiosis receptor-like kinase have defects in the entrapment of rhizobia and nodule formation, and like Mtnfp, are not responsive to Nod factors in Ca2+-spiking assays (Endre et al., 2002; Stracke et al., 2002; Limpens et al., 2003; Radutoiu et al., 2003; Ané et al., 2004; Imaizumi-Anraku et al., 2005; Kanamori et al., 2006; Saito et al., 2007; Oldroyd et al., 2011). Although the Mtlyk3/hcl mutants exhibit similar defects to the other mutants mentioned above, they show normal calcium spiking in response to Nod factors, in contrast to the others (Smit et al., 2007). Acting downstream of Ca2+ spiking the Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CCaMK/DMI3), which is thought to decode the Ca2+-spiking signal, activates gene transcription through activation of the transcription factor (TF) Interacting Protein of DMI3/Cyclops (Horváth et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2014). CCaMK is required for the formation of ITs and nodules, and constitutively active variants of CCaMK can initiate spontaneous nodule organogenesis (Catoira et al., 2000; Lévy et al., 2004; Gleason et al., 2006; Tirichine et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2013). In addition to Interacting Protein of DMI3/Cyclops, acting downstream of CCaMK are two transcription factors NSP1 and NSP2, and VAPYRIN, an ankyrin domain-containing protein of unknown function (Kaló et al., 2005; Smit et al., 2005; Messinese et al., 2007; Yano et al., 2008; Oldroyd et al., 2011). The above-mentioned genes, with the exception of the Nod factor receptor genes, MtNFP/LjNFR5, are required for both root nodule symbiosis and the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis, and constitute a common symbiotic pathway (Oldroyd et al., 2011; Delaux et al., 2013).

Several other genes are known that act downstream of CCaMK. NIN is a nodulation-specific TF required for formation of ITs and nodules. Mutations in other genes also lead to defective IT growth, including genes encoding the transcriptional regulators MtNF-YA1 (Laporte et al., 2014) and ERF transcription factor1 (ERN1, Middleton et al., 2007); regulators of actin nucleation, Nck-Associated Protein1 (LjNAP1/MtRIT1, Yokota et al., 2009; Miyahara et al., 2010), 121F-specific p53 Inducible RNA (Yokota et al., 2009), and Actin Related Protein Component1 (Hossain et al., 2012); membrane protein flotillin (FLOT2 and FLOT4, Haney and Long, 2010); SYMBIOTIC REMORIN 1 (Lefebvre et al., 2010); an E3 ligase Ubox/WD40, LUMPY INFECTIONS (Kiss et al., 2009); a U-box, WD-40 domain-containing protein (Yano et al., 2009); E3 ubiquitin ligase PUB1 (Mbengue et al., 2010); the cell wall enzyme Lotus Pectate Lyase gene (Xie et al., 2012); and the nuclear-localized coiled-coil protein, Rhizobium Polar Growth (Arrighi et al., 2008).

Very little is known about transcriptional regulation of genes involved in IT growth in legumes. Recently, it has been shown that LjCyclops is a TF that it is required for induction of NIN expression (Singh et al., 2014). Further, it has been shown that NIN binds to and activates the promoters of the Nodulation Pectate Lyase gene (LjNPL, Xie et al., 2012), LjNF-YA1, and LjNF-YB1, and the genes encoding two LjCLAVATA3/ENDOSPERM SURROUNDING REGION (CLE)-related small peptides, CLE ROOT SIGNAL (CLE1 and CLE2, Soyano et al., 2013, 2014).

Here we report on the identification and characterization of what is, to our knowledge, a novel gene, MtCBS1 encoding a protein with a cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) domain and a domain of unknown function (DUF21), which is required for IT propagation, bacterial endocytosis, and effective nitrogen fixation in Medicago.

RESULTS

Characterization of Two Independent Symbiotic Mutants

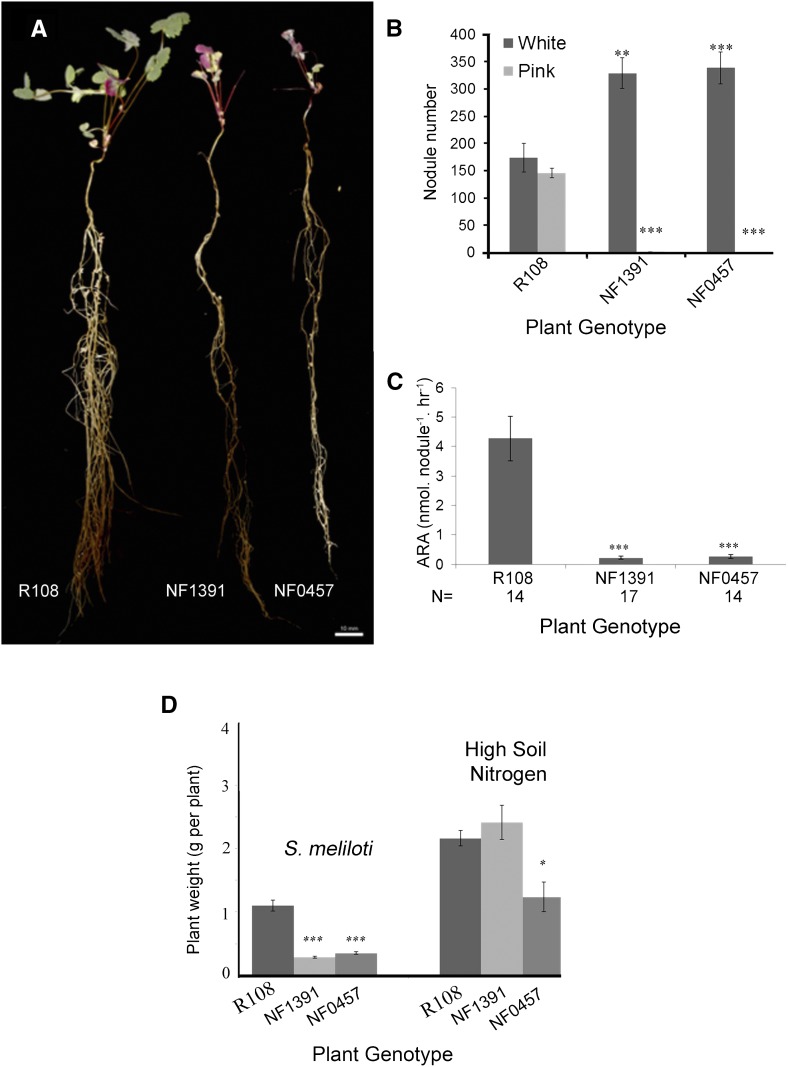

Tnt1-insertion mutant lines NF1391 and NF0457 were identified previously as having delayed nodulation and defects in IT formation (Pislariu et al., 2012). Homozygous mutants of both of these lines exhibited retarded growth compared to the wild-type R108 under symbiotic conditions (Fig. 1A) and developed only white nodules, in contrast to the mixture of white (immature) and pink (mature) nodules of the wild type (Fig. 1B). Acetylene reduction assays revealed greatly reduced activity at 21 dpi in NF1391 and NF0457 plants compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 1C). Growth defects of NF1391 and NF0457 plants under symbiotic conditions with low soil mineral nitrogen were fully or partially alleviated, respectively, by provision of a high concentration of mineral nitrogen (6 mm N from KNO3 and NH4NO3; Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Nodulation, nitrogen fixation, and growth phenotypes of the wild-type (R108), and NF1391 and NF0457 mutants. A, Plant growth 21 dpi with S. meliloti 1021. Wild type on left, followed by NF1391 and NF0457. B, Number of pink and white nodules at 70 dpi with S. meliloti 1021, n = 9. C, ARA of wild-type R108 and mutants at 21 dpi, n = 14–17. D, Plant fresh weights for wild-type and mutants grown with low nitrogen (0.5 mm nitrate supplied once) and inoculated with S. meliloti 1021 and harvested at 21 dpi, or supplemented with 2 mm each of KNO3 and NH4NO3 each week. Plants were harvested at 28 d post-planting, n = 11. Bars indicate ± se. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in plant performance with respect to the R108 control, determined using Student’s t test: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001. ARA, acetylene reduction activity.

To test whether the symbiotic mutations of NF1391 and NF0457 were dominant or recessive, mutant individuals were back-crossed (BC) to wild-type R108 plants and the resulting F1 individuals were self-fertilized to produce an F2 population. BC-F2 populations of both NF1391 and NF0457 segregated in a 3:1 ratio of wild type to mutant symbiotic phenotypes, indicating that the underlying mutations were monogenic-recessive (NF1391, 156 Fix+, and 46 Fix−, χ2 = 0.535, P > 0.05; and NF0457, 91 Fix+, and 17 Fix−, χ2 = 4.938, P > 0.05). Fix+ and Fix− phenotypes were scored based on plant growth, leaf color, and nodule size and color.

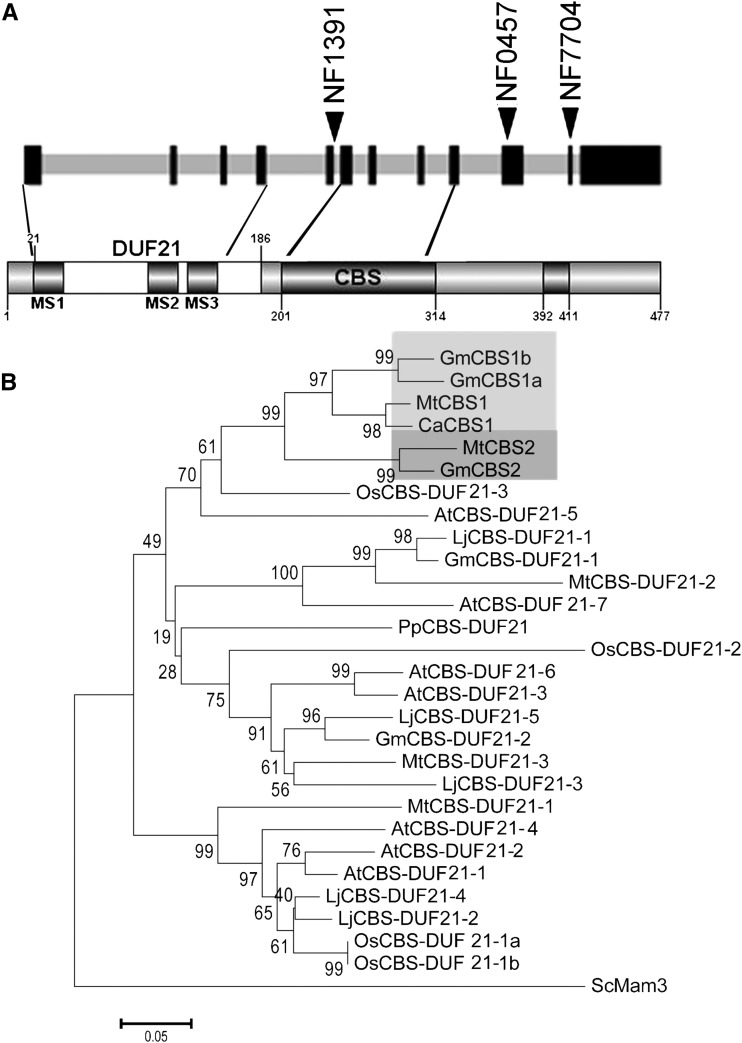

Identification and Characterization of a Novel (to our knowledge) Symbiotic Gene, MtCBS1

Genomic sequences flanking sites of Tnt1 integration in lines NF1391 and NF0457 were recovered by Thermal Asymmetric InterLaced PCR. Sequencing revealed 28 and 17 so-called flanking sequence tags in NF1391 and NF0457, respectively (Supplemental Table S1). To investigate potential candidates, we first checked the expression profiles of genes harboring Tnt1 insertions, using the Medicago truncatula Gene Expression Atlas (MtGEA; Benedito et al., 2008) and published data from rhizobially inoculated root hairs (Breakspear et al., 2014). Four genes were found with expression patterns indicating potential roles in symbiosis in line NF1391. These encoded a transmembrane protein (Medtr2g006280), a receptor-like kinase (Medtr8g088760), a zinc-finger domain-containing protein (Medtr8g076620), and a CBS domain-containing protein (Medtr6g052300). Oligonucleotide primers specific to these genes and the Tnt1 retrotransposon were used for plant genotyping (Supplemental Table S2). Genotyping of 46 mutants and four wild-type-like plants of line NF1391 from a BC-F2 population revealed that only one Tnt1 insertion cosegregated perfectly, in the homozygous state, with the mutant phenotype. This insertion was in the fifth intron of gene Medtr6g052300, between the invariant splice donor sites G and T at position 3595 relative to the start ATG. Bearing in mind that typically not all flanking sequence tags are recovered from Tnt1 mutant lines by Thermal Asymmetric InterLaced PCR, we tested whether symbiotic mutants of line NF0457 harbored an insertion in gene Medtr6g052300. PCR analysis revealed an insertion in the 10th exon of this gene at position 5649bp relative to the start ATG codon. Genotyping of this locus in the segregating BC-F2 population of NF0457 (17 mutants and 91 wild-type plants) revealed perfect co-segregation of the homozygous mutation and the phenotype. Medtr6g052300 encodes a protein with a centrally located CBS domain and an N-terminal domain of unknown function (DUF21; Fig. 2A). Therefore, we named the gene MtCBS1 and designated the two mutant alleles cbs1-1 (NF1391) and cbs1-2 (NF0457). An additional mutant allele, cbs1-3, with a Tnt1 insertion in exon 11 at position 6368 bp, was identified in line NF7704, via a BLAST search of the public mutant-database (http://bioinfo4.noble.org/mutant/; Fig. 2A). Homozygous cbs1-3 mutants were also found to be Fix− (data not shown), but as the mutant was discovered late in the course of this study it was not included in the experiments described here.

Figure 2.

MtCBS1 contains a predicted membrane-spanning domain of unknown function (DUF21) and a single cystathionine-β-synthase domain. A, Schematic representation of MtCBS1 gene structure (top) and conserved domains of the corresponding protein (bottom). Exons are represented by black rectangular boxes and introns with gray. Two domains (DUF21 and CBS) are indicated on the protein representation. The positions of the Tnt1 insertion sites for the different cbs1 alleles are indicated by arrowheads on the MtCBS1 gene structure. Three putative membrane-spanning domains (MS1–3) are predicted by the TopPred 1.10 program (http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/portal.py#forms::toppred) and marked as gray boxes along the protein; the numbers are amino-acid positions in the protein. B, Phylogeny of the MtCBS1-DUF21. Arabidopsis (At), C. arietinum (Ca), G. max (Gm), L. japonicus (Lj), M. truncatula (Mt), O. sativa (Os), P. patens (Pp), and S. cerevisiae (Sc). The bar represents the estimated amino-acid change per sequence position. The S. cerevisiae protein (CAY86228) is used to root the tree.

To confirm that the Tnt1 insertion in the CBS1 gene of mutant cbs1-1 was responsible for the symbiotic defects observed earlier, the mutant was transformed with either pro35S:CBS1 (CBS1 transcription driven by the constitutive 35S promoter) or proCBS1:CBS1:GFP (transcription of a CBS1:GFP fusion driven by the native CBS1 promoter), via hairy root transformation. Both constructs complemented the mutant phenotype, restoring normal development of elongated nodules and increasing acetylene reduction activity significantly compared to control plants transformed with the vector alone (Supplemental Fig. S1, A, B, C, D, and E).

CBS1 belongs to a family of proteins that contain N-terminal DUF21 and a C-terminal CBS domain (Fig. 2A). These proteins are uncharacterized in plants and only partially characterized in yeast in the case of MAM3p, which has a DUF21 and two CBS domains in tandem (Yang et al., 2005). Phylogenetic analysis of CBS1 protein homologs in Arabidopsis, i.e. Oryza sativa, Physcomitrella patens, M. truncatula, L. japonicus, Glycine max (soybean), Cicer arietinum (chickpea), and S. cerevisiae MAM3p, clustered MtCBS1 into a legume-specific clade with two soybean and one chickpea CBS domain-containing proteins (Fig. 2B). The closest branch to this cluster contains a second M. truncatula gene that we named MtCBS2 (Medtr6g051860; Fig. 2B), which also had a counterpart in soybean. MtCBS1 and MtCBS2 are tightly linked on chromosome 6. However, the two genes show contrasting expression patterns, based on data from MtGEA. MtCBS1 was expressed predominantly in nodules, while MtCBS2 expression was found only in mycorrhizal roots (Supplemental Fig. S2A).

MtCBS1 and MtCBS2 are 38% identical in predicted protein sequence (Supplemental Fig. S2C). In DUF21 of MtCBS1, 3 to 4 transmembrane domains were predicted by hydropathy analysis, while 4 to 5 transmembrane domains were predicted in the MtCBS2 protein (Supplemental Fig. S2 C). Topology predictions for the MtCBS1 and MtCBS2 proteins indicate that the C terminus is likely to be extracellular in both the proteins (Supplemental Fig. S3, A and B).

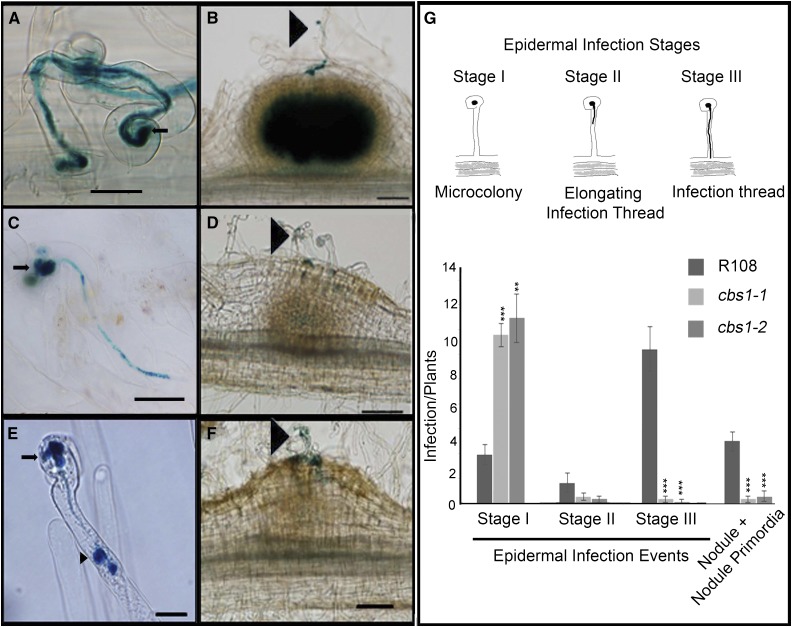

Infection Phenotypes of Mtcbs1 Mutants

The phenotype of Mtcbs1 mutants did not match those of previously described nodulation mutants. After inoculation with rhizobia, root hair cells of the cbs1-1 and cbs1-2 mutants produced almost normal shepherd’s crook structures (Fig. 3, A, C, and E) and a higher ratio of microcolonies to ITs than the wild-type (Fig. 3, B, D, F, and G). ITs in cbs1-1 and cbs1-2 were fewer in number, appeared to contain fewer bacteria, and often terminated growth within the root hair, resulting in a buildup of bacteria at the tip of the IT (Fig. 3, C and E). Consequently, fewer ITs reached the developing nodule primordia (Fig. 3, D, F, and G).

Figure 3.

Infection defects of cbs1-1 and cbs1-2 mutants at early stages of interaction with S. meliloti 1021. A, B, Wild-type (R108); C, D, cbs1-1; and E, F, cbs1-2. Representative micrographs of infection phenotypes; the presence of S. meliloti is visualized by β-Gal blue-staining. A, C, and E, Epidermal infection threads. C, E, Mutants have a large microcolony (marked by arrows) and halted IT (marked by arrow head), respectively. B, D, and F, Nodule formation was observed 7 dpi (ITs are marked by arrowheads). G, Average number of microcolonies, elongating ITs, full length or cortical ITs, and cortical events (nodules plus nodule primordia) in wild-type and mutant plants within 2.5 cm of the susceptible zone of the root at 7 dpi visualized using lacZ-expressing S. meliloti 1021. Mean ± se from n = 17 (R108), 11 (Mtcbs1-1), and 10 (Mtcbs1-2) plants. Asterisks indicate a significant difference by Student’s t test: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001. Scale bar, A, C, and E, 20 μm; B, D, and F, 100 μm.

To better define the symbiotic stage(s) affected in cbs1 mutants, we used calcofluor staining to visualize IT cell wall formation and GFP-labeled rhizobia (strain Sm1021) to follow bacterial entry. During bacterial entrapment in curled root hair cells, no difference was observed between mutant and wild-type R108 plants (compare Fig. 4, A, D, and G). Some microcolonies were observed with erratic deposition of cell wall material in mutant plants (compare Fig. 4B with Fig. 4, E and H). We estimated the frequency of the erratic deposition of IT cell wall material in mutant plants, based on calcofluor-white fluorescence. Calcofluor-white binds to β-1,3- and β-1,4-linked polysaccharides such as those found in cellulose or in chitin. We observed approximately 70% increase in fluorescence intensity around microcolonies (Supplemental Fig. S4, A, B, and C). At later stages, calcofluor-stained ITs devoid of rhizobia were observed in mutants but not the wild type (compare Fig. 4C with Fig. 4, F and I). Wild-type ITs always contained rhizobia. To summarize, defects in rhizobial infection in the mutant plants were first apparent during initiation of ITs from infection pockets, with production of larger and more numerous microcolonies and fewer ITs that, when present, contained few or no rhizobia.

Figure 4.

Infection phenotype of Mtcbs1. Confocal micrographs of rhizobial infection showing GFP-labeled S. meliloti 1021 (green); root hair and IT cell wall was stained with calcofluor white (blue, which binds to β-1,3 and β-1,4 polysaccharides) to monitor growth of the IT. A, B, C, wild type; D, E, F, cbs1-1; G, H, I, cbs1-2. Scale bar 10 μm. Empty ITs were marked by arrows. (I) The microcolony and empty IT are from two different root hair cells. The erratic deposition of IT walls are marked by arrows.

Calcium is a feature of the response of legume root cells to rhizobial bacteria and this occurs as both calcium oscillations associated with the nucleus and a calcium influx across the plasma membrane (Oldroyd, 2013). Genetic and cell biological studies have implied that the calcium influx may be associated with the formation of infection structures (Miwa et al., 2006; Morieri et al., 2013), and therefore we assessed calcium responses in the cbs1-1 mutant. We observed no defects in either the calcium influx or calcium oscillations (Supplemental Fig. S5), implying that CBS1 is not required for these signaling functions.

Bacterial Endocytosis Is Affected in cbs1

In view of the defects in early colonization via ITs in the cbs1 mutants, we investigated later aspects of the colonization process, using light and transmission-electron microscopy (TEM). Light microscopy using semi-thin sections of nodules with toluidine-blue staining revealed significant differences between cbs1 and wild-type nodules. The invasion zone (ZII) in cbs1 nodules was enlarged and there were fewer infected cells in the nitrogen-fixation zone (ZIII), compared to wild-type nodules (compare Fig. 5, A and B). In zone II of wild-type nodules, individual rhizobia could be seen within the IT matrix, which was not itself stained (Fig. 5C). In cbs1, the entire IT matrix was stained and individual bacteria could not be seen; therefore it was not possible to determine whether these ITs contained rhizobia or not (Fig. 5D). The reason for aberrant staining is unknown, but it could possibly be due to the ability of toluidine blue to stain acidic polysaccharides. In TEM micrographs, we noticed defects in transcellular ITs of the cbs1 mutant compared to wild-type (compare Supplemental Fig. S6, A, B, and C to Supplemental Fig. S6, D, E, F, G, H, and I). Nonetheless, large, normal-looking ITs filled with bacteria could be seen in cbs1, as in wild-type nodules (Supplemental Fig. S6, C and F). However, we also observed ITs containing abnormal, dark-colored bacteria, which we interpret as dead or dying (Supplemental Fig. S6I). In developing cbs1 nodules, bacteria were released from ITs into plant cells either by normal droplet formation, as in the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S6, B, C, and D), or via enlarged droplets (Supplemental Fig. S6, E, G, and H). Bacteria appeared abnormal just after endocytosis in the latter case (Supplemental Fig. S6, E, G, and H). Bacteroids within the nitrogen-fixing zone of cbs1 nodules appeared normal, showing characteristics of type IV bacteroids, including elongation, although there appeared to be fewer such bacteroids in the mutant than in the wild type (Fig. 5, G and H). Slower release of bacteria from ITs and/or more rapid degradation of bacteria could account for this difference.

Figure 5.

Cytological characterization of cbs1 mutant nodules during bacterial endocytosis. Semi-thin section of 11-dpi-old whole nodule from A, wild-type and B, cbs1-2 were stained with toluidine blue. High magnification light microscopic images from ZII of wild-type (C) and cbs1-2 (D) in an 11-dpi nodule showing defects in bacterial release from ITs in cbs1-2 nodules. High magnification light microscopic images from ZIII of wild type (E) and cbs1-2 (F). TEM images from ZIII wild type (G) and cbs1-2 (H) nodule cells at 11 dpi, showing symbiosomes. Note the low bacterial occupancy of infected cells in the mutant (compare E and G with F and H). M, meristem; V, vascular bundle; ZII, invasion zone; ZIII nitrogen fixation zone; S, starch granule. ITs are indicated by arrows, and degrading bodies are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bar: A, B, 20 μm; C, D, 10 μm.

Characterization of MtCBS1 Promoter Activity

As described above, the Mtcbs1-1 mutant phenotype was complemented with a wild-type copy of the CBS1 cDNA containing 1.5 kb of its own promoter. To determine the spatiotemporal expression pattern of the CBS1 gene after inoculation with rhizobia, we fused the 1.5 kb promoter region of CBS1 to the GUS reporter gene (proMtCBS1:GUS) and transformed this construct into plants via hairy root transformation. At 3 dpi, GUS activity in transgenic roots was detected in root hair cells containing ITs, and in neighboring epidermal cells (Fig. 6, A and B). Magenta-Gal staining of lacZ-expressing rhizobia together with GUS-staining confirmed that CBS1 promoter activity was associated with root hair cells containing ITs (Fig. 6C). During Medicago nodule primordia formation, cell division occurs initially in the pericycle and later in the inner cortex (Timmers et al., 1999; Xiao et al., 2014). GUS stain in proMtCBS1:GUS roots was always found in the epidermis and cortical cells (C1–C4 according to Xiao et al., 2014) but not in dividing cells of the pericycle or endodermis (Fig. 6, D, E, and F). At 6 dpi, GUS expression was found in cells associated with the propagating IT network as well as epidermal and cortical cells (Fig. 6E). In larger, more mature nodules at the same time point, GUS expression was associated with the meristem and invasion zone but was never found in the vascular bundle (Fig. 6F). In an intact nodule, at 15 dpi, GUS staining appeared restricted to the meristem and invasion zone (Fig. 6G). Nodule dissection showed more clearly the apical restriction of GUS staining (Fig. 6H). Magenta-Gal staining of bacteria together with GUS-staining confirmed that the CBS1 promoter was active primarily in the meristem and invasion zone (Fig. 6I), although some GUS staining was also observed in the epidermis of infected roots and the outer layer of cells in nodules (Fig. 6, A and E, respectively).

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of CBS1 during nodule development. X-Gluc (blue) staining for promCBS1:GUS expression and Magenta-Gal (purple) staining for lacZ S. meliloti infection were used. A, Root hairs in the infection zone, 3 dpi. GUS-stained ITs are indicated by arrows; B, a curled root hair cell shows GUS activity. C, A curled root hair cell containing an IT and the base of the root hair cell shows GUS activity. The IT is marked with an arrowhead. D, A dividing cortical cell shows GUS activity at 3 dpi and the associated infection event is shown by rhizobia Magenta-Gal staining and marked with an arrowhead. E, F, Developing nodule primordia show GUS activity associated with the invasion zone (6 dpi). G, H, I, The 15-dpi nodule shows that GUS activity is mainly associated with meristem and invasion zone; G, brief GUS staining for 3 h; H, section of nodule after GUS staining; I, GUS-stained sections of mature nodules were further counterstained with Magenta-Gal, which shows GUS activity associated with the meristem and invasion zones, with some staining in the nodule cortex. Bars represent A, F, H, I, 100 μm; B, C, D, 20 μm; E, 50 μm; and G, 1 mm. V, Vascular bundle; M, meristem; Ep, epidermis; Ed, endodermis; C1–C5, numbering of cortical cell layers of Medicago root from outside to inside according to Xiao et al. (2014).

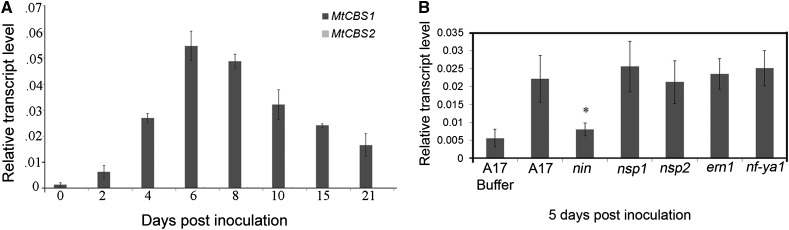

MtGEA data (Benedito et al., 2008; Czaja et al., 2012; http://mtgea.noble.org/v3/) show that MtCBS1 expression increased more than 2-fold and 4-fold, 6 and 24 h after Nod factor application, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2B). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis showed that MtCBS1 transcript levels increased steadily during nodulation between 2 and 6 dpi, then decreased between 8 and 21 dpi (Fig. 7A). MtCBS2 transcripts were not detected in these samples (Fig. 7A).To extend these results and identify potential regulators of CBS1 expression, we employed qRT-PCR to measure CBS1 transcript levels in seedlings of wild-type plants and five transcription factor mutants impaired at early stages of symbioses development, namely nin, nsp1, nsp2, ern1, and nf-ya1 (5 dpi Sinorhizobium meliloti). CBS1 transcript levels increased 4-fold in wild-type root hairs in response to inoculation, by 5 dpi, compared to uninoculated controls. Transcript levels were similar to the wild type in all inoculated transcription factor mutants, except nin in which CBS1 transcript level did not differ from the uninoculated control (Fig. 7B). Recently a NIN binding motif was identified in Lotus (TX12AGGX2T) (Soyano et al., 2013), and this motif is present twice in the 1.5-kb MtCBS1 promoter.

Figure 7.

CBS1 expression is induced during nodulation and under the control of NIN. A, Expression profile of CBS1 and CBS2 during nodule development in M. truncatula ecotype R108. qRT-PCR was used to measure CBS1 and CBS2 transcript levels relative to three housekeeping genes [MtPI4K (Medtr3g091400), MtPTB2 (Medtr3g090960), and MtUBC28 (Medtr7g116940)] in the infection-susceptible zone of roots (0–4 dpi) and in developing nodules (6–21 dpi). The mean of three biological replicates is presented in each case. Vertical bars represent ± sd. B, qRT-PCR analysis of isolated root hair cells from wild-type A17 and five transcription factor mutants (nin, nsp1, nsp2, ern1, and hap2.1) in the A17 background at 5 dpi with S. meliloti. Mean and sd (vertical bars) of three biological replicates are presented in each case. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in CBS1 expression with respect to the control by Student’s t test: * P ≤ 0.05.

MtCBS1-GFP Protein Localizes to the Infection Thread and Symbiosome Space

As described above, the proCBS1:CBS1:GFP transgene complemented the cbs1 phenotype (Supplemental Fig. S1, A, B, and E). Therefore, the same construct was used in an attempt to localize the CBS1:GFP fusion protein in the cells of transformed hairy roots. Unfortunately, no significant GFP fluorescence was detected in root hair cells using this construct (data not shown). To visualize CBS1:GFP, we tested a stronger and rhizobia-inducible promoter for root hair expression, namely the ENOD12 promoter (Breakspear et al., 2014). Following hairy root transformation with the proENOD12:MtCBS1:GFP-containing construct, we detected GFP fluorescence along the ITs at 7 dpi (Fig. 8A). Some auto-fluorescence was observed in rhizobia-infected root hair cells, but never in ITs of nontransformed root cells (Supplemental Fig. S7A). Notably, pronounced auto-fluorescence was seen in the shepherd’s-crook structure of root hairs. The enlargement of the micrograph shows the localization of CBS1:GFP fusion protein largely in the infection thread matrix (Fig. 8B and Supplemental Fig. S7, C, D, and E). Using the proCBS1:CBS1:GFP construct at 15 dpi, CBS1:GFP fluorescence was associated with the symbiosome (Figs. 8, C, D, E, F, and G). GFP fluorescence was adjacent to and largely separate from the red mCherry fluorescence of bacteroids (see the enlarged picture of Fig. 8, E, F, and G), indicating a location for CBS1 in the symbiosome space or the symbiosome membrane. Symbiosome-associated green fluorescence was not visible in nontransformed nodules from the same plant (Supplemental Fig. S7B).

Figure 8.

CBS1-GFP localizes to ITs and symbiosomes. A, with mCherry-expressing S. meliloti 1021 (red) in a brightest-point projection of a spinning disk confocal stack merged (1), GFP only (2), and mCherry only (3). B, A merged field of a single z-section showing the CBS1:GFP (green) along the IT matrix, S. meliloti 1021 (red). C, D, E, F, G, promCBS1-driven CBS1:GFP (green) localization in the infection zone 12 dpi with S. meliloti 1021 (red). C, D, Brightest-point projection of a spinning disk confocal stack, shows CBS1:GFP protein localization around bacteroids. D, GFP-only field of (C). E, F, G, Higher-magnification micrograph showing CBS1:GFP protein localized to the symbiosome space. E, F, Merged field. G, The GFP-only field showing the CBS1:GFP localization in the symbiosome space. Arrows indicate localization of the CBS1:GFP protein. A, B, C, D, E, Scale bar = 10 μm; F, G, scale bar = 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

The results presented above indicate that MtCBS1 is a protein that localizes to the infection thread matrix and symbiosome, and which is required for effective infection and colonization by rhizobia of nodule epidermal and cortical cells. The cbs1 mutants displayed multiple defects during infection and colonization, including increased numbers of bacterial microcolonies in infection pockets that were often enlarged, indicating a problem in initiation of ITs (Fig. 3, C, E, and G); and fewer ITs that traversed the length of root hairs, with many ITs having uncolonized sections (Figs. 3, C and G and 4, F and I), perhaps indicating an IT environment unsuitable for bacterial cell division and/or colonization. ITs that formed in cbs1 mutants often terminated in occlusions (Fig. 3E). Few ITs reached the base of root hair cells in cbs1 mutants and went on to colonize the nodule primordia (Figs. 3, C and E, and 4, F and I). In these cases, an additional defect was evident during endocytosis of bacteria into nodule cells: the presence of swollen ITs implicates CBS1 in bacterial endocytosis (Fig. 5, B and D). The few bacteria that were released from ITs into the plant cell cytoplasm formed normal symbiosomes capable of fixing nitrogen (Fig. 1C).

Although other mutants with defects in IT formation have been characterized previously, phenotypes of these mutants differ from those of cbs1 in several ways. Before they terminate within the root hair, ITs in cbs1 appear similar to those of the wild type in terms of thickness in contrast to the rpg mutant, which has abnormally thick ITs (Arrighi et al., 2008). Like rpg, the nf-ya1 mutant also has thickened, slowly progressing ITs that appear bulbous and swollen (Laporte et al., 2014). The lin/cerberus, Ljcyclops, and vpy mutants form abnormal-looking ITs that terminate very early in the root hairs (Kuppusamy et al., 2004; Yano et al., 2009; Murray 2011). The recently reported arf16a mutant has a decreased number of microcolonies (Breakspear et al., 2014), while microcolony numbers in cbs1 were increased relative to wild type. The ern1 and cbs1 phenotypes are superficially similar, each featuring ITs that appear structurally normal but that often terminate in bulbous occlusions within the root hair (Middleton et al., 2007). Unlike cbs1, however, ern1 nodules are not infected and do not fix nitrogen. With respect to microcolony formation, cbs1 is most similar to the Lotus Ljnpl mutant, which is defective for a pectate lyase enzyme. Ljnpl had increased numbers of microcolonies, similar to cbs1. Like cbs1, Ljnpl is defective in IT initiation from the infection pocket within the root hair curl. However, unlike cbs1, Ljnpl ITs became colonized normally but they traversed cell wall boundaries poorly (Xie et al., 2012).

CBS1 displayed a complex expression pattern during Medicago nodule development. The gene was induced within 6 h of Nod factor treatment (Fig. 7A), and its expression was associated with infected root hair cells, infected outer cortical tissues, and the nodule invasion zone (Fig. 6). Our results suggest that CBS1 induction is dependent on NIN but not NF-YA1, which requires NIN for its expression (Soyano et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2014). It is not clear from our work whether CBS1 is a direct target of NIN or if other yet-unidentified TF(s) act downstream of NIN to activate MtCBS1. In L. japonicus, LjCBS1 (Lotus probeset IDs: LjSGA_0673396.1, Lj_SGA_111594.1) expression is reduced in the Ljnin mutant compared to the wild-type, indicating a conserved genetic program in legumes (Høgslund et al., 2009; Soyano et al., 2013; Verdier et al., 2013).

Expression of MtCBS1:GFP fusion protein during nodulation resulted in green fluorescence associated with the IT and symbiosome (Fig. 8, C, D, and E). This localization is consistent with our promoter-GUS study that showed CBS1 expression in cells undergoing infection by rhizobia, the nodule meristem, and invasion zone. The MtCBS1:GFP appeared to localize to the IT matrix and the symbiosome space or symbiosome membrane. However, the presence of a predicted membrane-spanning domain (DUF21) in CBS1 is inconsistent with it being secreted. On the other hand, it should be noted that GFP was fused to the C terminus of CBS1, and the predicted extracellular C terminus of the protein is on bacterial side toward the IT matrix and symbiosome space. It is not inconceivable that after being deposited into the membrane, the GFP portion is cleaved from the fusion protein. Normal symbiosomes can form in the cbs1 mutant, albeit at a much lower frequency, suggesting CBS1 is not required for symbiosome formation per se. However, rapid degradation of symbiosomes in the mutant could be due to the absence of CBS1 protein in the symbiosome space/membrane. Clearly, further work is required to determine the exact mode of action of CBS1 protein.

CBS domain-containing proteins are evolutionarily conserved and present in all forms of life (Bateman, 1997). CBS domains occur in tandem, with the exception of plants, which have single as well as paired-domain CBS proteins. In animals, CBS pair domain proteins usually act as regulatory subunits in enzyme complexes (Kushwaha et al., 2009). CBS domain proteins are mostly regulatory subunits associated with, and required for, the function of several enzymes of unrelated function, such as inosine 5′ monophosphate dehydrogenase, AMP-activated protein kinase, chloride channels, and CBS (Baykov et al., 2011). Mutations in CBS domains impair the function of the associated enzymes (Kushwaha et al., 2009). Enzyme activation by CBS proteins occurs through binding to s-adenosyl-Met, AMP, or ATP, which changes the CBS pair domain structure and thereby activates the enzyme (Kushwaha et al., 2009; Yoo et al., 2011).

Topology prediction suggested that the CBS domain of MtCBS1 is extracellular (Supplemental Fig. S3), ostensibly facing the IT matrix and the symbiosome space. By interacting with other proteins in these compartments, MtCBS1 may alter the membrane, cell wall, or solutes surrounding the rhizobia. Identifying which proteins, if any, interact with MtCBS1 may shed light on the enzymatic or other functions associated with this protein, which could help us to understand why loss of MtCBS1 function leads to aberrant infection and colonization of root and nodule cells.

The most closely related protein to CBS1 that has been characterized is MAM3p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. MAM3p has a DUF21 and two CBS domains. It is a vacuolar membrane protein whose expression levels directly correlate to the degree of manganese toxicity, but it does not impart any obvious changes in vacuolar accumulation of metals (Yang et al., 2005). We tested MtCBS1 for manganese transport activity in oocyte cells, but it did not show such activity (data not shown). Single CBS domain- and DUF21-containing proteins are present only in plants. The Arabidopsis and rice genomes code for seven and four DUF21-CBS proteins, respectively (Kushwaha et al., 2009), the function of which are unknown. MtCBS1 is the first plant DUF21-CBS protein that has been tied to a biological function. The closest homolog of MtCBS1 is Arabidopsis AtCBS-DUF21-5 (At5g52790) and its expression is restricted to roots. Transcriptomic studies revealed that At5g52790 expression changed in a root hair cell-wall deformation mutant (Diet et al., 2006). This is intriguing, in light of the defects in the ITs of cbs1 mutants, and the putative location of the CBS domain in the lumen of ITs. Perhaps, as we speculated above, MtCBS1 is involved in formation of the IT wall. Interestingly, in Arabidopsis it has been shown that a single soluble CBS domain-containing protein regulates cellular redox homeostasis by interacting with thioredoxin and thereby controls maturation of the cell wall (Yoo et al., 2011). Currently, it is thought that regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the IT is important to ensure an appropriate level of cross linking within the plant cell wall to maintain its integrity while allowing IT growth and bacterial infection (Santos et al., 2001; Brewin, 2004; Jamet et al., 2007). Reduction of ROS by overexpression of the S. meliloti catalase, katB, impaired IT development, suggesting that a fine balance of ROS production in the IT is required for its proper development (Jamet et al., 2007). Consistent with a possible role of CBS1 in cell wall chemistry, the gene was found to be regulated by H2O2 (Andrio et al., 2013). Based on our results and analysis of the literature, our favored hypothesis at present is that CBS1 affects IT cell wall maturation, possibly via ROS metabolism. Further biochemical studies are needed to understand the exact role of CBS1 in IT and symbiosome development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth and Bacterial Strains

Medicago truncatula ecotype R108 and homozygous cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) mutants cbs1-1 and cbs1-2) were used. Seeds were scarified for 10 min in H2SO4 followed by sterilization for 3 min with 30% (v/v) commercial bleach containing a few drops of Tween 20. Surface-sterilized seeds were placed on inverted plates containing damp, sterile filter paper in the dark for 3 d at 4°C and 1 d at 20°C. Germinated seedlings were transferred to plastic cones containing a 2:1 ratio of turface/vermiculite. Plants were cultivated under a 16-h/8-h light/dark regime with 200 μE m−2 s−2 light irradiance at 21°C and 40% relative humidity. After 7 d of growth, plants were inoculated with 50 mL of Sinorhizobium meliloti [strains Sm1021 with pXLGD4 plasmid (Boivin et al., 1990) or Sm1021 with mCherry-expressing or GFP-expressing plasmid]. S. meliloti was grown overnight in TY (tryptone yeast extract) liquid medium, with shaking at 250 rpm, to OD600 approximately 1.0, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in half-strength Broughton and Dilworth solution (Broughton and Dilworth, 1971) with 0.5 mm KNO3 at OD600 approximately 0.02. For root transformation, ARqua1 Agrobacterium rhizogenes was used. For the high soil nitrogen experiment, 6 mM mineral nitrogen was applied every week.

Mutant Screening and Cloning of the cbs1-1 Gene

The mutants cbs1-1 and cbs1-2 were isolated during research community screening workshops at The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation (Pislariu et al., 2012). Cloning of the CBS1 gene was done by Thermal Asymmetric InterLaced PCR and flanking sequence tag sequencing as previously described (Tadege et al., 2008). Thermal Asymmetric InterLaced PCR was done on NF1391 (cbs1-1) and NF0457 (cbs1-2) using a combination of Tnt1-specific primers (Tnt1-F1, Tntail 1, 2, 3, and LTR3 or LTR5) and arbitrary primers AD1 or AD2 (Supplemental Table S1). Back-crossing of homozygous cbs1-1 and cbs1-2 mutants with the R108 accession was performed as described by Taylor et al. (2011). All the above-mentioned experiments were performed on a back-crossed homozygous mutant population for both the cbs1-1 and cbs1-2 alleles including a growth or developmental phenotype under symbiotic and high nitrogen conditions.

Complementation of the cbs1 Mutant Phenotype

The open reading frame of CBS1 was amplified from cDNA synthesized with total RNA extracted from 4 dpi nodules of the ecotype R108 using the Trizol RNA extraction method (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). PCR products were cloned into a Gateway destination vector pB7WG2D (Karimi et al., 2002). This generated a MtCBS gene under a 35S promoter. A native promoter and CBS1 gene fusion were generated in two steps. At the first step, each PCR fragment was generated with a flanking sequence from another portion of the gene; in the second step, these fragments were stitched together with a second round of PCR (primers are in Supplemental Table S1). The final round of PCR was done using Phusion DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), and the promoter cDNA fusion PCR product was cloned into a modified pKGW-RedRoot vector. In pKGW-RedRoot, an eGFP has been introduced after the Gateway cassette so that ultimately a C-terminal GFP fusion protein would be generated under the control of the native promoter. The eGFP and 35S terminator were PCR-amplified from pK7FWG2. The empty vector expressing only the GFP gene (pK7WGF2) and nontransformed root from the same plant were used as a control during the protein localization studies. For ENDO12::CBS-GFP construct generation, the ENOD12 promoter was further incorporated into the pKGW-RedRoot-eGFP vector using AatII restriction digestion and PCR fragment cloning (primers are in Supplemental Table S1). The above-generated vectors were incorporated into A. rhizogenes strain ARqua 1. Agrobacteria were infected on cbs1-1 and R108 seedlings to generate composite plants (Boisson-Dernier et al., 2001). Transformed hairy roots were screened either under UV or green light.

Nodulation Assays and Sample Collection

For nodulation, time-course assays were done in the manner described in Sinharoy et al. (2013). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on three biological replicates. Transcript levels were normalized using the geometric average of three housekeeping genes: ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 (Medtr7g116940), polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (Medtr3g090960), and phosphoinositide 4-kinase γ4 (Medtr8g027610), the transcript levels of which were stable across all the samples analyzed (primers are in Supplemental Table S1).

Histochemical Staining Light, Confocal, and Transmission Electron Microscopy

Images of whole-mount nodulated roots were captured using a model no. SZX12 stereomicroscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) equipped with a model no. DXM1200C digital camera (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Histochemical staining with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) was performed as described previously (Boivin et al., 1990). For root hair imaging, whole-mount images were captured using a model no. BX41 compound microscope (Olympus). Whole roots were mounted on a slide with 60% glycerol and used for microscopy. Detached nodules were embedded in 5% low-melting-point agarose and sliced into 50-μm-thick sections with a 1000 Plus Vibratome (The Vibratome Company, Technical Product International, St. Louis, MO). In Fig. 3C, two different focal planes of the same image were superimposed using Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). For protein localization, plants were freshly harvested, transformed roots were selected by red fluorescence, and either whole roots were mounted in 20% glycerol containing 100 mm Tris 7.5 for protein localization in root hair cells or 12-dpi nodules were hand-sectioned and mounted similarly. Further samples were observed under a Spinning Disk Confocal Microscope (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). For time-course confocal microscopy, whole mounted roots were stained with calcofluor (Life Technologies) and nodule development was followed using GFP-labeled Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. Images were acquired with a model no. TCS SP2 AOBS Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). For transmission electron microscopy, nodules were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde (v/v) and 4% paraformaldehyde (v/v) in cacodylate buffer, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in LR white resin (London Resin Company, Reading, Berkshire, UK). Serial 0.1-μm sections were cut with a diamond knife on a model no. EM UC7 Ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems). Ultrathin sections were then put onto carbon-coated copper grids and stained with 2% uranyl acetate followed by staining with Sato’s lead. Specimens were observed under a model no. 10A Transmission Electron Microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) operated at 80 kV. Images captured on negative films were scanned and digitized. All digital micrographs were processed using Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems).

Calcium Spiking Assay

Calcium spiking assay was performed through microinjection as described in Miwa et al. (2006) in wild type (R108) and cbs1-1 mutant background. Fluorescence images were taken over the entire root-hair cell using a model no. TE2000U inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) coupled to a Hamamatsu Photonics digital CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan).

Acetylene Reduction Assay

Acetylene reduction assays were performed as described previously (Oke and Long, 1999). Plants were grown on a mixture of vermiculite and turface, watered with B and D solution containing 0.5 mm nitrate, and inoculated with rhizobia Sm1021. At 21 d post-inoculation, entire root systems were placed into sealed test tubes for the assays for 16–18 h.

Gene Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis

Homologous proteins for MtCBS1 were identified by BLAST search in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, Bethesda, MD). The highest homologous 25 sequences were downloaded from Phytozome v9.1. The Arabidopsis and rice database contains seven and four MtCBS1 homologous proteins, respectively (Kushwaha et al., 2009); they were downloaded in addition to the 25 sequences. S. cerevisiae MAM3 protein was used to root the tree. The full-length protein sequences of the MtCBS1 were aligned using the ClustalW program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) in MEGA 6.06 (http://www.megasoftware.net/). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 6.06 (Tamura et al., 2013) using the neighbor-joining method. The bootstrap test (10,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. In Figure 1 the CBS domain is predicted according to the SUPERFAMILY 1.75 software (http://supfam.org/SUPERFAMILY/) and the protein domain is drawn by using Domain Graph (DOG) v2 (http://dog.biocuckoo.org/down.php).

RNA Isolation from Isolated Root Hairs

Wild-type M. truncatula (Jemalong A17), nin, nsp1, nsp2, ERF transcription factor1, and nfya1 (hap2-1), were grown and root hair was isolated according to Breakspear et al. (2014). RNA was isolated using an RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and contaminating DNA was removed using the TURBO DNA-free Kit (Ambion, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was done using the CBS1 specific primer mentioned in Supplemental Table S2.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data for this article can be found in the Phytozome v9.1, for L. japonicus; the protein ID is according to the L. japonicus genome database and the chickpea ID is according to Legume Information Systems: GmCBS1a (Glyma09g24130.1), GmCBS1b (Glyma16g29610.1), MtCBS1 (Mdtr6g052300.1), CaCBS1 (Cam:101496956), MtCBS2 (Mdtr6g051860.1), GmCBS2 (Glyma09g24150.1), MtCBS-DUF21-1 (IMGA|Medtr7g010900.1), LjCBS-DUF21-2 (chr6.CM0139.810.r2.d), LjCBS-DUF21-4 (chr4.CM0387.650.r2.a), AtCBS-DUF21-1 (At4g14240.1), AtCBS-DUF21-2 (At4g14230.1), AtCBS-DUF21-3 (At2g14520.1), AtCBS-DUF21-4 (At1g03270.1), AtCBS-DUF21-5 (At5g52790.1), AtCBS-DUF21-6 (At4g33700.1), AtCBS-DUF21-7 (At1g47330.1), OsCBSDUF21-1a (Os5g32850.1), OsCBSDUF21-1b (Os5g32850.2), OsCBSDUF21-2 (Os3g47120.1), OsCBSDUF21-3 (Os3g03430.1), MtCBS-DUF21-2 (IMGA|contig_10415_1.1), LjCBS-DUF21-1 (LjCM0492.170.r2.), GmCBS-DUF21-1 (Glyma04g03440.1), PpCBS-DUF21 (Pp1s196_114V6.1), LjCBS-DUF21-3 (chr6.CM0055.40.r2.m), MtCBS-DUF21-3 (IMGA|Medtr2g010520.1), GmCBS-DUF21-2 (Glyma07g30470.2), LjCBS-DUF21-5 (Ljchr4.CM1616.380.r2.m). The MtCBS1 sequence from the Medicago R108 genotype was submitted to GenBank (accession no. KJ746967). Arabidopsis and Oryza CBS-DUF21 domain numbering was done according to Kushwaha et al. (2009).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Complementation of the cbs1-1 mutant with prom35S:CBS1 or promCBS1:MtCBS1:GFP constructs via Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation.

Supplemental Figure S2. Comparison between CBS1 and CBS2 gene expression and domain composition.

Supplemental Figure S3. Topology prediction of CBS1 and CBS2 according to the TopPred 1.10 program (http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/portal.py#forms::toppred).

Supplemental Figure S4. Visualization of cell wall material around microcolonies via calcofluor white fluorescence.

Supplemental Figure S5. NF-induced Ca2+ spiking patterns in wild-type and Mtcbs1 M. truncatula root hair cells.

Supplemental Figure S6. Transcellular infection threads inside the wild type and cbs1 nodules.

Supplemental Figure S7. Localization of CBS1-GFP protein.

Supplemental Table S1. Gene IDs of flanking sites of Tnt1 integration in lines NF1391 and NF0457.

Supplemental Table S2. Primer files.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Phil Poole for providing the mCherry rhizobia strain, and Conner Boatright and Kurtis Cressman (Ohio State University) for assistance with the nodulation assay; Janie Gallaway and Frank Coker for technical assistance in maintaining the M. truncatula Tnt1 lines; and Dan Roberts and Pratyush Routray for testing CBS1 transporter activity. We also thank Pascal Ratet, Kirankumar S. Mysore, and Million Tadege for the construction of the Tnt1 mutant population, Mark Taylor for back-crossing the mutant, and Gregory W. Strout and The Samuel Roberts Noble Microscopy Laboratory at the University of Oklahoma for supporting TEM.

Glossary

- BC

back-crossed

- CBS, cbs

cystathionine-β-synthase

- CCaMK

Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase

- CLE

LjCLAVATA3/ENDOSPERM SURROUNDING REGION

- DUF

domain of unknown function

- ERN1, ern1

ERF transcription factor1

- IT

infection thread

- Ljnfr5, Mtnfp

Nod factor perception mutants

- LjNPL, Ljnpl

Nodulation Pectate Lyase gene

- MtCBS, Mtcbs

M. truncatula Cystathionine-β-Synthase-like

- MtGEA

Medicago truncatula Gene Expression Atlas

- NIN, nin

nodulation-specific transcription factor

- Nod

nodulation factor

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Present address is Department of Biotechnology, University of Calcutta, 35, Ballygaunge Circular Road, Calcutta 700019, India.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Andrio E, Marino D, Marmeys A, de Segonzac MD, Damiani I, Genre A, Huguet S, Frendo P, Puppo A, Pauly N (2013) Hydrogen peroxide-regulated genes in the Medicago truncatula-Sinorhizobium meliloti symbiosis. New Phytol 198: 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ané JM, Kiss GB, Riely BK, Penmetsa RV, Oldroyd GE, Ayax C, Lévy J, Debellé F, Baek JM, Kaló P, Rosenberg C, Roe BA, et al. (2004) Medicago truncatula DMI1 required for bacterial and fungal symbioses in legumes. Science 303: 1364–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi JF, Barre A, Ben Amor B, Bersoult A, Soriano LC, Mirabella R, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Journet EP, Ghérardi M, Huguet T, Geurts R, Dénarié J, et al. (2006) The Medicago truncatula lysin [corrected] motif-receptor-like kinase gene family includes NFP and new nodule-expressed genes. Plant Physiol 142: 265–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi JF, Godfroy O, de Billy F, Saurat O, Jauneau A, Gough C (2008) The RPG gene of Medicago truncatula controls Rhizobium-directed polar growth during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 9817–9822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A. (1997) The structure of a domain common to archaebacteria and the homocystinuria disease protein. Trends Biochem Sci 22: 12–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baykov AA, Tuominen HK, Lahti R (2011) The CBS domain: a protein module with an emerging prominent role in regulation. ACS Chem Biol 6: 1156–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Amor B, Shaw SL, Oldroyd GE, Maillet F, Penmetsa RV, Cook D, Long SR, Dénarié J, Gough C (2003) The NFP locus of Medicago truncatula controls an early step of Nod factor signal transduction upstream of a rapid calcium flux and root hair deformation. Plant J 34: 495–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedito VA, Torres-Jerez I, Murray JD, Andriankaja A, Allen S, Kakar K, Wandrey M, Verdier J, Zuber H, Ott T, Moreau S, Niebel A, et al. (2008) A gene expression atlas of the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J 55: 504–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin C, Camut S, Malpica CA, Truchet G, Rosenberg C (1990) Rhizobium meliloti genes encoding catabolism of trigonelline are induced under symbiotic conditions. Plant Cell 2: 1157–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakspear A, Liu C, Roy S, Stacey N, Rogers C, Trick M, Morieri G, Mysore KS, Wen J, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA, Murray JD (2014) The root hair “infectome” of Medicago truncatula uncovers changes in cell cycle genes and reveals a requirement for Auxin signaling in rhizobial infection. Plant Cell 26: 4680–4701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin NJ. (2004) Plant cell wall remodelling in the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Crit Rev Plant Sci 23: 293–316 [Google Scholar]

- Broughton WJ, Dilworth MJ (1971) Control of leghaemoglobin synthesis in snake beans. Biochem J 125: 1075–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisson-Dernier A, Chabaud M, Garcia F, Bécard G, Rosenberg C, Barker DG (2001) Agrobacterium rhizogenes transformed roots of Medicago truncatula for the study of nitrogen-fixing and endomycorrhizal symbiotic associations. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14: 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catoira R, Galera C, de Billy F, Penmetsa RV, Journet EP, Maillet F, Rosenberg C, Cook D, Gough C, Dénarié J (2000) Four genes of Medicago truncatula controlling components of a nod factor transduction pathway. Plant Cell 12: 1647–1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja LF, Hogekamp C, Lamm P, Maillet F, Martinez EA, Samain E, Dénarié J, Küster H, Hohnjec N (2012) Transcriptional responses toward diffusible signals from symbiotic microbes reveal MtNFP- and MtDMI3-dependent reprogramming of host gene expression by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal lipochitooligosaccharides. Plant Physiol 159: 1671–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaux PM, Bécard G, Combier JP (2013) NSP1 is a component of the Myc signaling pathway. New Phytol 199: 59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diet A, Link B, Seifert GJ, Schellenberg B, Wagner U, Pauly M, Reiter WD, Ringli C (2006) The Arabidopsis root hair cell wall formation mutant lrx1 is suppressed by mutations in the RHM1 gene encoding a UDP-L-rhamnose synthase. Plant Cell 18: 1630–1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt DW, Wais R, Long SR (1996) Calcium spiking in plant root hairs responding to Rhizobium nodulation signals. Cell 85: 673–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre G, Kereszt A, Kevei Z, Mihacea S, Kaló P, Kiss GB (2002) A receptor kinase gene regulating symbiotic nodule development. Nature 417: 962–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J, Teillet A, Chabaud M, Ivanov S, Genre A, Limpens E, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Barker DG (2015) Remodeling of the infection chamber before infection thread formation reveals a two-step mechanism for rhizobial entry into the host legume root hair. Plant Physiol 167: 1233–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J, Timmers AC, Sieberer BJ, Jauneau A, Chabaud M, Barker DG (2008) Mechanism of infection thread elongation in root hairs of Medicago truncatula and dynamic interplay with associated rhizobial colonization. Plant Physiol 148: 1985–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason C, Chaudhuri S, Yang T, Muñoz A, Poovaiah BW, Oldroyd GE (2006) Nodulation independent of rhizobia induced by a calcium-activated kinase lacking autoinhibition. Nature 441: 1149–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney CH, Long SR (2010) Plant flotillins are required for infection by nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 478–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høgslund N, Radutoiu S, Krusell L, Voroshilova V, Hannah MA, Goffard N, Sanchez DH, Lippold F, Ott T, Sato S, Tabata S, Liboriussen P, et al. (2009) Dissection of symbiosis and organ development by integrated transcriptome analysis of Lotus japonicus mutant and wild-type plants. PLoS One 4: e6556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horváth B, Yeun LH, Domonkos A, Halász G, Gobbato E, Ayaydin F, Miró K, Hirsch S, Sun J, Tadege M, Ratet P, Mysore KS, et al. (2011) Medicago truncatula IPD3 is a member of the common symbiotic signaling pathway required for rhizobial and mycorrhizal symbioses. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24: 1345–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MS, Liao J, James EK, Sato S, Tabata S, Jurkiewicz A, Madsen LH, Stougaard J, Ross L, Szczyglowski K (2012) Lotus japonicus ARPC1 is required for rhizobial infection. Plant Physiol 160: 917–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi-Anraku H, Takeda N, Charpentier M, Perry J, Miwa H, Umehara Y, Kouchi H, Murakami Y, Mulder L, Vickers K, Pike J, Downie JA, et al. (2005) Plastid proteins crucial for symbiotic fungal and bacterial entry into plant roots. Nature 433: 527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamet A, Mandon K, Puppo A, Hérouart D (2007) H2O2 is required for optimal establishment of the Medicago sativa/Sinorhizobium meliloti symbiosis. J Bacteriol 189: 8741–8745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaló P, Gleason C, Edwards A, Marsh J, Mitra RM, Hirsch S, Jakab J, Sims S, Long SR, Rogers J, Kiss GB, Downie JA, et al. (2005) Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators. Science 308: 1786–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori N, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Frantescu M, Quistgaard EM, Miwa H, Downie JA, James EK, Felle HH, Haaning LL, Jensen TH, Sato S, et al. (2006) A nucleoporin is required for induction of Ca2+ spiking in legume nodule development and essential for rhizobial and fungal symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 359–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Inzé D, Depicker A (2002) GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci 7: 193–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss E, Oláh B, Kaló P, Morales M, Heckmann AB, Borbola A, Lózsa A, Kontár K, Middleton P, Downie JA, Oldroyd GE, Endre G (2009) LIN, a novel type of U-box/WD40 protein, controls early infection by rhizobia in legumes. Plant Physiol 151: 1239–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppusamy KT, Endre G, Prabhu R, Penmetsa RV, Veereshlingam H, Cook DR, Dickstein R, Vandenbosch KA (2004) LIN, a Medicago truncatula gene required for nodule differentiation and persistence of rhizobial infections. Plant Physiol 136: 3682–3691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushwaha HR, Singh AK, Sopory SK, Singla-Pareek SL, Pareek A (2009) Genome wide expression analysis of CBS domain containing proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh and Oryza sativa L. reveals their developmental and stress regulation. BMC Genomics 10: 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte P, Lepage A, Fournier J, Catrice O, Moreau S, Jardinaud MF, Mun JH, Larrainzar E, Cook DR, Gamas P, Niebel A (2014) The CCAAT box-binding transcription factor NF-YA1 controls rhizobial infection. J Exp Bot 65: 481–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre B, Timmers T, Mbengue M, Moreau S, Hervé C, Tóth K, Bittencourt-Silvestre J, Klaus D, Deslandes L, Godiard L, Murray JD, Udvardi MK, et al. (2010) A remorin protein interacts with symbiotic receptors and regulates bacterial infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 2343–2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévy J, Bres C, Geurts R, Chalhoub B, Kulikova O, Duc G, Journet EP, Ané JM, Lauber E, Bisseling T, Dénarié J, Rosenberg C, et al. (2004) A putative Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for bacterial and fungal symbioses. Science 303: 1361–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens E, Franken C, Smit P, Willemse J, Bisseling T, Geurts R (2003) LysM domain receptor kinases regulating rhizobial Nod factor-induced infection. Science 302: 630–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EB, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Olbryt M, Rakwalska M, Szczyglowski K, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J (2003) A receptor kinase gene of the LysM type is involved in legume perception of rhizobial signals. Nature 425: 637–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbengue M, Camut S, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Deslandes L, Froidure S, Klaus-Heisen D, Moreau S, Rivas S, Timmers T, Hervé C, Cullimore J, Lefebvre B (2010) The Medicago truncatula E3 ubiquitin ligase PUB1 interacts with the LYK3 symbiotic receptor and negatively regulates infection and nodulation. Plant Cell 22: 3474–3488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinese E, Mun JH, Yeun LH, Jayaraman D, Rougé P, Barre A, Lougnon G, Schornack S, Bono JJ, Cook DR, Ané JM (2007) A novel nuclear protein interacts with the symbiotic DMI3 calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase of Medicago truncatula. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20: 912–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton PH, Jakab J, Penmetsa RV, Starker CG, Doll J, Kaló P, Prabhu R, Marsh JF, Mitra RM, Kereszt A, Dudas B, VandenBosch K, et al. (2007) An ERF transcription factor in Medicago truncatula that is essential for Nod factor signal transduction. Plant Cell 19: 1221–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB, Pratap A, Miyahara A, Zhou L, Bornemann S, Morris RJ, Oldroyd GE (2013) Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase is negatively and positively regulated by calcium, providing a mechanism for decoding calcium responses during symbiosis signaling. Plant Cell 25: 5053–5066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H, Sun J, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA (2006) Analysis of Nod-factor-induced calcium signaling in root hairs of symbiotically defective mutants of Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19: 914–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyahara A, Richens J, Starker C, Morieri G, Smith L, Long S, Downie JA, Oldroyd GE (2010) Conservation in function of a SCAR/WAVE component during infection thread and root hair growth in Medicago truncatula. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 23: 1553–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morieri G, Martinez EA, Jarynowski A, Driguez H, Morris R, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA (2013) Host-specific Nod-factors associated with Medicago truncatula nodule infection differentially induce calcium influx and calcium spiking in root hairs. New Phytol 200: 656–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JD. (2011) Invasion by invitation: rhizobial infection in legumes. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24: 631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oke V, Long SR (1999) Bacterial genes induced within the nodule during the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Mol Microbiol 32: 837–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE. (2013) Speak, friend, and enter: signalling systems that promote beneficial symbiotic associations in plants. Nat Rev Microbiol 11: 252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE, Murray JD, Poole PS, Downie JA (2011) The rules of engagement in the legume-rhizobial symbiosis. Annu Rev Genet 45: 119–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples MB, Brockwell J, Herridge DF, Rochester IJ, Alves BJR, Urquiaga S, Boddey RM, Dakora FD, Bhattarai S, Maskey SL, Sampet C, Rerkasem B, et al. (2009) The contributions of nitrogen-fixing crop legumes to the productivity of agricultural systems. Symbiosis 48: 1–17 [Google Scholar]

- Pislariu CI, Murray JD, Wen J, Cosson V, Muni RR, Wang M, Benedito VA, Andriankaja A, Cheng X, Jerez IT, Mondy S, Zhang S, et al. (2012) A Medicago truncatula tobacco retrotransposon insertion mutant collection with defects in nodule development and symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Plant Physiol 159: 1686–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Felle HH, Umehara Y, Grønlund M, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J (2003) Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature 425: 585–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Yoshikawa M, Yano K, Miwa H, Uchida H, Asamizu E, Sato S, Tabata S, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Umehara Y, Kouchi H, Murooka Y, et al. (2007) NUCLEOPORIN85 is required for calcium spiking, fungal and bacterial symbioses, and seed production in Lotus japonicus. Plant Cell 19: 610–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos R, Hérouart D, Sigaud S, Touati D, Puppo A (2001) Oxidative burst in alfalfa-Sinorhizobium meliloti symbiotic interaction. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14: 86–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Katzer K, Lambert J, Cerri M, Parniske M (2014) CYCLOPS, a DNA-binding transcriptional activator, orchestrates symbiotic root nodule development. Cell Host Microbe 15: 139–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinharoy S, Torres-Jerez I, Bandyopadhyay K, Kereszt A, Pislariu CI, Nakashima J, Benedito VA, Kondorosi E, Udvardi MK (2013) The C2H2 transcription factor regulator of symbiosome differentiation represses transcription of the secretory pathway gene VAMP721a and promotes symbiosome development in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 25: 3584–3601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit P, Limpens E, Geurts R, Fedorova E, Dolgikh E, Gough C, Bisseling T (2007) Medicago LYK3, an entry receptor in rhizobial nodulation factor signaling. Plant Physiol 145: 183–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit P, Raedts J, Portyanko V, Debellé F, Gough C, Bisseling T, Geurts R (2005) NSP1 of the GRAS protein family is essential for rhizobial Nod factor-induced transcription. Science 308: 1789–1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyano T, Hirakawa H, Sato S, Hayashi M, Kawaguchi M (2014) Nodule inception creates a long-distance negative feedback loop involved in homeostatic regulation of nodule organ production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 14607–14612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyano T, Kouchi H, Hirota A, Hayashi M (2013) Nodule inception directly targets NF-Y subunit genes to regulate essential processes of root nodule development in Lotus japonicus. PLoS Genet 9: e1003352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke S, Kistner C, Yoshida S, Mulder L, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J, Szczyglowski K, Parniske M (2002) A plant receptor-like kinase required for both bacterial and fungal symbiosis. Nature 417: 959–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadege M, Wen J, He J, Tu H, Kwak Y, Eschstruth A, Cayrel A, Endre G, Zhao PX, Chabaud M, Ratet P, Mysore KS (2008) Large-scale insertional mutagenesis using the Tnt1 retrotransposon in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J 54: 335–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Blaylock L, Nakashima J, McAbee D, Ford J, Harrison M, Udvardi M (2011) Medicago truncatula hybridization: Supplemental videos. In Medicago truncatula Handbook Version July 2011 U. Mathesius, E.P. Journet, and L.W. Sumner, eds (Ardmore, Oklahoma: The Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation), pp 1–5 http://www.noble.org/MedicagoHandbook/ [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30: 2725–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers AC, Auriac MC, Truchet G (1999) Refined analysis of early symbiotic steps of the Rhizobium-Medicago interaction in relationship with microtubular cytoskeleton rearrangements. Development 126: 3617–3628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirichine L, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Yoshida S, Murakami Y, Madsen LH, Miwa H, Nakagawa T, Sandal N, Albrektsen AS, Kawaguchi M, Downie A, Sato S, et al. (2006) Deregulation of a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase leads to spontaneous nodule development. Nature 441: 1153–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier J, Torres-Jerez I, Wang M, Andriankaja A, Allen SN, He J, Tang Y, Murray JD, Udvardi MK (2013) Establishment of the Lotus japonicus Gene Expression Atlas (LjGEA) and its use to explore legume seed maturation. Plant J 74: 351–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wais RJ, Galera C, Oldroyd G, Catoira R, Penmetsa RV, Cook D, Gough C, Denarié J, Long SR (2000) Genetic analysis of calcium spiking responses in nodulation mutants of Medicago truncatula. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 13407–13412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao TT, Schilderink S, Moling S, Deinum EE, Kondorosi E, Franssen H, Kulikova O, Niebel A, Bisseling T (2014) Fate map of Medicago truncatula root nodules. Development 141: 3517–3528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F, Murray JD, Kim J, Heckmann AB, Edwards A, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA (2012) Legume pectate lyase required for root infection by rhizobia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 633–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Jensen LT, Gardner AJ, Culotta VC (2005) Manganese toxicity and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mam3p, a member of the ACDP (ancient conserved domain protein) family. Biochem J 386: 479–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K, Shibata S, Chen WL, Sato S, Kaneko T, Jurkiewicz A, Sandal N, Banba M, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Kojima T, Ohtomo R, Szczyglowski K, et al. (2009) CERBERUS, a novel U-box protein containing WD-40 repeats, is required for formation of the infection thread and nodule development in the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis. Plant J 60: 168–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K, Yoshida S, Müller J, Singh S, Banba M, Vickers K, Markmann K, White C, Schuller B, Sato S, Asamizu E, Tabata S, et al. (2008) CYCLOPS, a mediator of symbiotic intracellular accommodation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20540–20545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota K, Fukai E, Madsen LH, Jurkiewicz A, Rueda P, Radutoiu S, Held M, Hossain MS, Szczyglowski K, Morieri G, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA, et al. (2009) Rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton mediates invasion of Lotus japonicus roots by Mesorhizobium loti. Plant Cell 21: 267–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo KS, Ok SH, Jeong BC, Jung KW, Cui MH, Hyoung S, Lee MR, Song HK, Shin JS (2011) Single cystathionine β-synthase domain-containing proteins modulate development by regulating the thioredoxin system in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 3577–3594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.