Abstract

We examine the life, work, and legacy of Clara Haber, nee Immerwahr, who became the first woman to earn a doctorate from the University of Breslau, in 1900. In 1901 she married the chemist Fritz Haber. With no employment available for female scientists, Clara freelanced as an instructor in the continued education of women, mainly housewives, while struggling not to become a housewife herself. Her duties as a designated head of a posh household hardly brought fulfillment to her life. The outbreak of WWI further exacerbated the situation, as Fritz Haber applied himself in extraordinary ways to aid the German war effort. The night that he celebrated the “success” of the first chlorine cloud attack, Clara committed suicide. We found little evidence to support claims that Clara was an outspoken pacifist who took her life because of her disapproval of Fritz Haber's involvement in chemical warfare. We conclude by examining “the myth of Clara Immerwahr” that took root in the 1990s from the perspective offered by the available scholarly sources, including some untapped ones.

Keywords: Clara Haber‐Immerwahr, Fritz Haber

1 Introduction

On April 23, 1909, Clara Haber wrote to her PhD adviser and confidant, Richard Abegg, the following lines:1

“What Fritz [Haber] has gained during these last eight years, I have lost, and what's left of me, fills me with the deepest dissatisfaction.”

This sobering summary of an eight‐year marriage with Fritz Haber, a leading chemist of his time, may serve as a key document about Clara's life and fate, not least in regard to her suicide six years hence.

Our paper examines the life, work, and legacy of Clara Haber as well as the possible motive for her voluntary exit from life at age 45. We aim to make a distinction between what's known about Clara based on scholarly sources and the “myth of Clara Immerwahr,” which took root about two decades ago and constitutes her public image today.

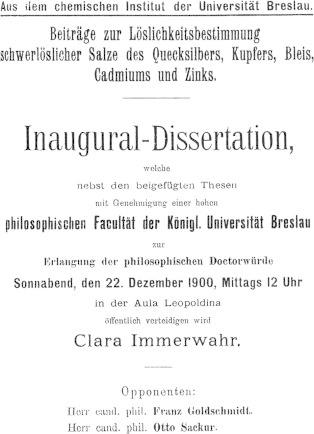

Clara Haber, nee Immerwahr: A Biographical Outline

The timeline of Clara's life is shown in Figure 1. She was born in 1870 at the estate of Polkendorf near Breslau, where her father, a PhD chemist, withdrew after the failure of his chemical start‐up company.2 Apart from becoming a highly successful agronomist in Polkendorf and surroundings, he co‐owned a flourishing specialty store in Breslau dealing in luxury fabrics and carpets. The Immerwahrs maintained an apartment in Breslau, which they inhabited during their frequent visits to the city. And Clara would live there during her studies in Breslau.

Figure 1.

Timeline of Clara Haber's life.

Breslau, characterized by Goethe as a “noisy, dirty and stinking” town,3 transformed itself during the second half of the 19th century into a prosperous metropolis teeming with business and industrial enterprise. This was accompanied by an enormous increase in population, which doubled between 1875 and 1905, reaching 471 thousand then.4 At the same time, Breslau developed into a major center of science and culture with a large educated middle‐class. There was the Schlesische Friedrich‐Wilhelms‐Universität, founded in 1811, a number of colleges, as well as an opera house, several orchestras, and a city theater – all of them of national significance.

The era of academic and cultural prosperity that the city had enjoyed coincided with the childhood and youth of Clara Immerwahr, whose family belonged to Breslau's well‐to‐do Jewish middle class. After Berlin and Frankfurt, the Jewish community of Breslau was the third largest, at over 20 thousand Jewish residents,4 and its synagogue, consecrated in 1872, even the second largest in Germany.5 Breslau's Jewish community was academically oriented and represented the city's “intellectual aristocracy,” to which also the Immerwahrs belonged. However, they were assimilated Jews, who participated in communal cultural life but would only rarely, if at all, go to the Synagogue. Jewish religion, customs, and practices played essentially no role in the family life. The political attitudes of the Immerwahr family were liberal, which however entailed the cultivation and demonstration of a certain degree of Prussian‐German national awareness and patriotism, especially after the German unification of 1871.6 Prussian was also the simple lifestyle of the family, which was frugal – not because of need but out of principle. So despite the family's wealth, Clara and her siblings were brought up in modesty.2

Apart from the virtues of simplicity, frugality, and modesty, a great value was attached to education – not just for the son and heir, but also for the three daughters, cf. Figure 1. This was typical for the German Jewish middle class, as 40 % of female students at the higher schools in Breslau were Jewish. As opposed to Switzerland or the Anglo‐Saxon countries, German high schools (Gymnasium) were out of limits for women until the beginning of the 20th century. The land of Baden was the first in Germany to institute admission of female students to universities. Before then, it was only possible for women to attend university by a special permission or as a guest auditor.7

Clara's path to education – and the life that came along with it – was shaped by these constraints. She started her studies at a Höhere Töchterschule (sometime translated as “Women's college”) in Breslau,8 which was supplemented during the summer months spent at the Polkendorf estate by instruction provided by a private tutor. Clara graduated from the Töchterschule at age 22. The school was supposed to provide a basic education for young women that was compatible with their social status and to prepare them for their “natural purpose,” that is as companions of their husbands, as housewives, and as mothers. Nevertheless, Clara was up for more and after graduating from the Töchterschule she entered a teachers' seminary, which was the only kind of institution that offered a higher professional education to women.9 However, the graduates of the teachers' seminary only qualified to teach at girls' schools and remained ineligible to enter university and study, e.g., science, which was what Clara wanted to do. So in order to qualify for her science studies at the university, Clara had to take intensive private lessons and pass an exam equivalent to the Abitur. This exam was administered by a special committee set up at a Realgymnasium in Breslau and Clara passed it successfully at Easter 1896,10 when she was 26 years old.

Subsequently, she began her studies at the University of Breslau, however only as a guest auditor, since in Prussia women would become legally admissible as university students only as late as 1908. Prior to this, starting in 1895, women were only allowed to attend lectures as guests, and even that was contingent upon the support of the professor and faculty and a permission from the Ministry; the last required a good‐conduct certificate, character references, etc. Talk about “intellectual Amazons” was not uncommon. It is difficult today to imagine what it meant to women to break into the male domain and what kind of discrimination and humiliation was connected with it.

This is shown by the attitude of Max Planck, who accepted Lise Meitner as an assistant in 1912 and was helpful in promoting her career even earlier, declared in 1895, in response to a poll, that:11

“Nature herself prescribed a role for women as mothers and housewives.”

Thus according to the spirit of the time, Clara Immerwahr, with her wish to become a chemist, violated a law of Nature. After her successful Abitur exam, Clara applied at the university curator's office for a permission to attend lectures in experimental physics as a guest. And she had to proceed in a similarly awkward manner with all the other lecture courses that she wished to take.

From early on, Clara developed a keen interest in the then new field of physical chemistry, cf. Figure 1. Richard Abegg, one of this new field's pioneers and a friend of Fritz Haber, played a key role in fostering Clara's interest in physical chemistry, while paying little heed to Clara's guest auditor status.12 It was also Abegg who supervised Clara's PhD Thesis – a part of the graduation requirement in Chemistry – and who wrote a joint paper with Clara in 1899. The joint paper, published in 1900 (see next Section and references cited therein), must have been perceived by the young female chemist as a proof of her success and an accolade. Next year, Clara submitted her dissertation and applied to be admitted to the Rigorosum final, which entailed exams in chemistry, physics, mineralogy, and philosophy. She passed the exams during the fall and defended her thesis at the university's main auditorium on December 22, 1900 (see Figure 2).

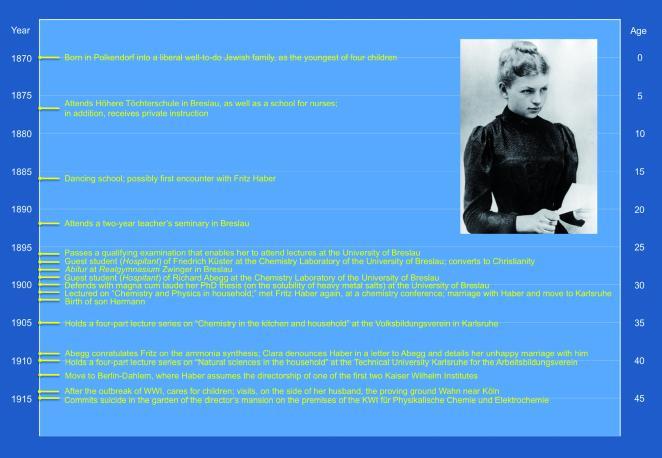

Figure 2.

Announcement of Clara Immerwahr's PhD Thesis defense at the main auditorium of the University of Breslau on 22 December 1910. Clara's Kommilitones Franz Goldschmidt and Otto Sackur were appointed as referees.

Clara graduated with magna cum laude and her graduation was mentioned in the daily press, as she was the first woman, on which the University of Breslau conferred a doctoral degree.13

2 Clara's Mentor and Confidant: Richard Abegg

Richard Abegg (see Figure 3) was Fritz Haber's Kommilitone at the Berlin university. Like Haber, he studied chemistry under August Wilhelm von Hofmann and graduated in 1891. Abegg's father was a successful banker who became a member of the Imperial Committee that supervised the German navy.14 Abegg's brothers likewise achieved high political rank.

Figure 3.

Left panel: Richard Abegg (*1869 Danzig; †1910 Tessin). Abegg graduated in chemistry from the Berlin University (1891) under August von Hofmann, received his Habilitation (1894) under Walther Nernst, was Extraordinarius at the University of Breslau (1899–1909), Ordinarius of the Technische Hochschule Breslau (1909), member of the Leopoldina (1900) and editor of the Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie (1901). Central panel: Otto Sackur (*1880 Breslau; †1914 Berlin). Sackur graduated in chemistry from the University of Breslau (1901) under Richard Abegg, received his Habilitation (1905) under Richard Abegg, and was department head at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry (1914). Right panel: Fritz Haber (*1868 Breslau; †1934 Basel). Haber graduated in chemistry from the Berlin university (1891) under August von Hofmann, received his Habilitation (1894) under Hans Bunte, was Extraordinarius (1898) and Ordinarius (1906) at the Technische Hochschule Karlsruhe, founding Director of the KWI für Physikalische Chemie und Elektrochemie (1911–1933), Honorarprofessor (1912–1920) and Ordinarius (1920–1933) at the Berlin University, and Member of the Prussian Academy (1914). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1918.

After his studies Abegg joined, in turn, the laboratories of the founders of physical chemistry, Wilhelm Ostwald in Leipzig, Svante Arrhenius in Stockholm, and finally Walther Nernst in Göttingen, where he received his Habilitation.15 As a physical chemist, he could have hardly had a better training.16

Let us note that physical chemistry came about with a purpose, namely to save chemistry from taxonomy – from becoming a collection of little disconnected facts bred mainly by organic chemists. Its founders shared the view that chemistry should seek the general rather than cherish the particular and that the way to achieve it was to adopt the methods of mathematics and physics.16 The success of physical chemistry in providing a common ground for chemistry was celebrated by Ostwald in his proclamation that “Physical chemistry is not just a branch on but the blossom of the tree of knowledge.”17

In 1899 Abegg assumed an academic position at the Chemistry Institute of the University of Breslau. Headed since its founding in 1897 by Albert Ladenburg, a distinguished chemist trained by Robert Bunsen and August Kekule, the institute belonged to the most prestigious in Germany. In 1909 Abegg became Ordinarius at the newly founded Technical University in Breslau.18 However he would not live long enough to see through the construction of the new laboratory for physical chemistry at the Technical University, which was slated to be his own.15 Abegg was an early fan of balloon flying – and founded and presided over the Breslau ballooning club. He died in a ballooning accident in 1910 at the age of 41.

As Nernst colorfully narrated in his obituary notice,15 Abegg was extremely hard‐working, yet had always time for everybody. That must have surely made him into an ideal academic teacher and adviser, particularly for Clara.

3 Clara's Kommilitone: Otto Sackur

Otto Sackur (see Figure 3) was Clara's ten‐year junior Kommilitone, who studied chemistry at the University of Breslau, where, like Clara, he found an enlightened mentor in Richard Abegg. Sackur further advanced his chemistry education at Heidelberg and Berlin before receiving his doctorate from Breslau in 1901. A year earlier, he served on Clara's PhD committee as a referee (cf. Figure 2).

Sackur's accomplishments can serve as a reference point for Clara's, not only because of their similar academic pedigrees, but also because they lived and struggled contemporaneously, often at the same places.

Sackur's academic career at Breslau took a detour, first through the Imperial Public Health Institute (Kaiserliches Gesundheitsamt) in Berlin. Subsequently, he joined William Ramsey's chemistry laboratory at University College London and then Walther Nernst's brand new laboratory at the University of Berlin. The latter stays brought him up to speed in physical chemistry research. Upon his return to Breslau, he completed his Habilitation and became Privatdozent, teaching and working side‐by‐side with Abegg. Two unfortunate events shattered Sackur's hopes for a more secure position: the replacement in 1909 of Albert Ladenburg as director of the chemistry department by the 1907 Nobel Prize winner Eduard Buchner (1860–1917), a fermentation biochemist, who harbored little sympathy for physical chemistry; a year later, Richard Abegg died tragically in a ballooning accident, as noted above. This left Sackur without an academic patron and a laboratory. In order to survive, Sackur had to rely on his pedagogical skills, accepting minor teaching assignments, devising a course of chemistry for dentists, and writing textbooks on thermodynamics,19 one of them with Abegg.20 It was during this period that Sackur launched his research at the intersection of thermodynamics and quantum theory. A reward in the form of a more senior appointment came at the end of 1913 when, thanks in part to mediation by Clara Haber, Sackur received a call to Haber's Kaiser‐Wilhelm‐Institut in Berlin. In 1914 he was promoted to the rank of a department head. After the outbreak of WWI he was enlisted in military research at Haber's institute, but continued on the side his experiments on the behavior of gases at low temperatures. In December of 1914, he was killed in a laboratory accident at his work bench – while trying to tame cacodyl chloride for use as an irritant and propellant.21 He was just 34 years old. In response to this tragedy, Fritz Haber halted explosives research at his institute.

Sackur is remembered as a pioneer of quantum statistical mechanics, known for deriving a quantum expression for the entropy of a gas, the Sackur‐Tetrode equation.21

4 The Scientific Work of Clara Immerwahr

Clara's scientific record consists of three research papers,22–24 an erratum,25 and a supplement26 to one of the research papers (see Figure 4). Her first research paper is co‐authored by her PhD adviser, Richard Abegg, the other two are solo. The second solo paper is an excerpt from Clara's PhD Thesis. Clara's work concerns solution chemistry, one of the main preoccupations of physical chemistry of the time, and revolves about the connections among the conductivity, solubility, degree of dissociation, electrochemical potential, and what was called electro‐affinity.

Figure 4.

Clara Immerwahr's scientific record as revealed by the Web of Science.

The paper with Abegg, which expands on the ideas of the 1899 Abegg‐Bodländer paper that introduced the notion of electro‐affinity as an organizing principle in chemistry,27 pretty much determined the topic and methodology of Clara's thesis paper. The thesis paper deals in a more systematic way with the interplay between solubility of choice heavy metal salts and the electro‐affinities of the constituent groups and atoms. Apart from providing tables of experimentally determined values of quantities such as equilibrium concentrations and relative electrode potentials, the paper aims at assessing the issue of whether electro‐affinities were additive quantities. The latter might be the reason for a relatively high number of citations this paper has so far received. However, one should keep in mind that quite a few of the publications citing Clara's paper are recent biographical articles about Clara rather than scientific papers.

Clara's second paper aimed to expand the solubility data base to include copper salts, using the ideas and methods developed by Walther Nernst, Wilhelm Ostwald, and Friedrich Wilhelm Küster. The last was Clara's professor at the University of Breslau, who also deserves credit for arousing her interest in physical chemistry. He moved to the Bergakademie in Clausthal in 1899 and it was in Küster's Clausthal laboratory that Clara undertook the measurements reported in her second paper. As she noted, her data could be regarded as a corroboration of the Nernst‐Ostwald‐Küster theory.

Clara's PhD adviser Richard Abegg became well known for his work on valence that led to the octet rule. Clara's work on electro‐affinity was somewhat related to this line of Abegg's research, but her contribution was not deemed significant enough to warrant Clara's inclusion in Svante Arrhenius's list of half a dozen or so of Abegg's former affiliates who had contributed to Abegg's research the most.14 To be sure, Sackur was not on that list either. However, Sackur made a name for himself in a research area that lay outside of Abegg's range of interests and published his key work only after Abegg's death. It should also be noted that Clara's work, unlike Abegg's or Sackur's, did not seek to enrich the conceptual framework of physical chemistry in any way or to launch a new research direction.

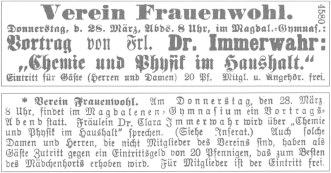

Apart from her work as a researcher, Clara also gave public lectures; both in Breslau and later in Karlsruhe, on the broad topic of science in the household (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Announcement of Clara Immerwahr's public talk entitled “Chemistry and Physics in the Household” on 28 March 1901 at the Breslau association Frauenwohl.

5 Clara's Husband: Fritz Haber

Apart from Abegg and Sackur, there was another pioneer of physical chemistry who entered Clara Immerwahr's life, namely Fritz Haber (see Figure 3). Likewise a native of Breslau, Fritz likely met Clara in a dancing class.2 Little is known about this liaison, but Haber would later admit, at the occasion of his engagement with Clara in April 1901, that he was “in love with [his bride] as a [high‐school] student” and that during the intervening years he had “honestly but unsuccessfully” tried to forget her.28 When the freshly minted Dr. Immerwahr appeared in April 1901 at the annual conference of the German Electrochemical Society in Freiburg – by the way as the only female scientist – the affair between her and Haber was quickly rekindled. As Haber would put it later in one of his letters,29 “we saw each other, we spoke and in the end Clara let herself be persuaded to give it a try with me.” Clara would give the rationale for her acceptance of Fritz's advances in the already mentioned 1909 letter to her confidant Abegg:1

“It has been my approach to life that it was only then worth living if one developed all one's abilities to the utmost and lived through everything that a human life can offer. And so I finally settled upon the idea of marriage […] under the impulse that if I did not marry, a decisive page in the book of my life and a string of my soul would lie idle. But the boost that I got from it was very short.”

As Margit Szöllösi‐Janze, the biographer of both Fritz and Clara Haber, pointed out, their wedding, which took place already on August 3, 1901, marked the end of “the chapter ‘chemical science' in Clara's book of life”, which “must have been clear to the chemist” even without “any effects on the string of her soul.”2

Upon looking at the last decade of Clara's life, one has to agree. Although at the beginning she might have harbored the hope that she would be able to resume her scientific work at some point, she must have increasingly cut down on such hopes as time went on. During the first years of her marriage, Clara appeared at lectures as well as in the laboratories of the Technische Hochschule in Karlsruhe, where her husband would soon become the founding director of its institute for physical chemistry.

Moreover, it seems that at the time Fritz Haber would involve his wife in his research and share with her his scientific ideas, as suggested by the dedication of his 1905 classic textbook Thermodynamics of technical gas‐reactions:30

“To my dear wife Clara Haber, Ph.D., in gratitude for her silent co‐operation.”

However, Clara was apparently not involved in doing any calculations for the book, as implied by the fact that this task fell to others.30 Nevertheless, that Clara's involvement in Haber's research entailed more than a silent co‐operation transpires in her correspondence with Abegg, in which she reports about Haber's progress in writing the textbook, discusses academic appointments, and solicits advice about her own public talks. However, the dream of an equitable and reciprocal scientific marriage – such as that of Pierre and Marie Curie in Paris – did not come true.

The turning point likely occurred when their son Hermann was born in 1902 and/or when Haber became Ordinarius at Karlsruhe in 1906, cf. Figure 1. Hermann was a sickly child, who claimed much of his mother's attention. Clara cared for the son lovingly, while at the same time running a demanding household (see Figure 6), and becoming sickly herself. At the beginning, the young family could not afford service staff and so Clara had to do a lot by herself. In a letter to Abegg written in 1901 from Karlsruhe,31 Clara declared that she would get back to the laboratory:

Figure 6.

Upper panel: The first apartment (on the belle etage) of the Habers, at Moltkestrasse 31 in Karlsruhe. Lower panel: Directorial mansion of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin‐Dahlem, the residence of the Habers since 1912. Design by the chief imperial architect Ernst von Ihne.

“…once we become millionaires and will be able to afford servants. Because I cannot even think about giving up my [scientific work].”

As we know, the Habers did become rich, but Clara would never return to the laboratory nevertheless. As years went by, she would fall increasingly into the traditional role of a representative professorial wife, a housewife preoccupied with the well‐being of the family, and a caring mother. This was aggravated by Haber's elbow mentality and his obsession with his work and career, which left little room for Clara's professional development and reduced her more and more to a house‐mother. Clara broke down as a result and, as Szöllösi‐Janze put it:2

“the heyday that Haber had lived through in Karlsruhe was for his wife Clara a time of intellectual dimming.”

Clara saw it herself and committed her feelings to paper in her letter to Abegg from April 23, 1909, where she said:1

“[Fritz is a type of person] on the side of whom every other person who does not force his way even more recklessly at the other's expense than him, will perish. And that is the case with me.”

There are still six years left until Clara's voluntary exit from life. During this time Fritz Haber would enjoy further scientific and social ascent: in 1909, he laid the scientific foundations for the catalytic synthesis of ammonia from its elements and in 1911 he became the founding director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin.

Thereby Haber reached not only the Olympus of science in Germany but of science full stop. Clara could partake in the glory of it all – however not as a scientist but rather as a spouse of a scientist, a difference that Clara surely must have reflected upon. The growing alienation of the couple was obvious to their contemporaries for whom:32

“the wearing down and the difficulties between the spouses were not of a petty kind but rather fundamental.”

The strains and conflicts between Clara and Fritz further aggravated after the outbreak of WWI. In keeping with his maxim “in peace for mankind, in war for the fatherland”, Fritz Haber applied himself in extraordinary ways to aid the German war effort.33,34

Like other scientists, Haber put himself at the disposal of the Ministry of War as a consultant, where, at the beginning, his advice was sought on issues of industrial chemistry in general and the ammonia synthesis in particular.2 The Haber‐Bosch process, patented in 1910, made it possible to fix nitrogen from air with hydrogen and thereby transform it to a form, in which it could be metabolized by plants. This in turn enabled an unlimited production of fertilizers and thus of “bread from air,” making Haber into one of mankind's greatest benefactors ever. Current estimates indicate that about two sevenths of humankind would not be able to survive in the absence of the Haber‐Bosch process. About a half of the nitrogen atoms in the body of today's European or American went through the Haber‐Bosch process.35

Apart from yielding “bread from air,” the ammonia synthesis also enabled the production of “gunpowder from air,” its primary employment in fact, which drove the implementation of the Haber‐Bosch process on an industrial scale. Without it, the German military would have run out of ammunition by 1915 at the latest.36

In part encouraged by the French use of tear gas37 – including its lethal variants – Haber took the initiative to employ chemistry in resolving the greatest strategic challenge of the war, namely the stalemate of trench warfare. Brought to prominence by Germany's need to produce “gunpowder from air,” Haber was able to persuade his country's military leadership to stage a battlefield test of a chemical weapon – of “poison instead of air.” This would earn him the epithet “father of chemical warfare.”

Haber celebrated the “success” of the German chlorine cloud attack on April 22, 1915 at Ypres and his promotion to the rank of captain38 at a gathering in his directorial mansion in Dahlem. The gathering took place on May 1, 1915. During the night from May 1 to May 2, Clara Haber committed suicide. She shot herself, with Haber's army pistol, in the garden of their mansion (cf. Figure 6). Clara was found dying by Habers' son Hermann. Haber, unable to secure a permission to stay, left the next evening for the Eastern front.2

In 1920, the Swedish Royal Academy awarded the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Fritz Haber, “for the synthesis of ammonia from its elements.” Both the laudatory address by the president of the Academy and Haber's Nobel lecture left out the issue of “gunpowder from air” altogether – not to speak about Haber's involvement in chemical warfare.

During the Weimar era, Haber's institute would become a world‐renowned center of research at the intersection of chemistry and physics.39 In contrast to many of his colleagues, Haber embraced the Weimar Republic and ranked among its open supporters. Still, neither his great scientific merits nor his unbridled patriotism sufficed to stave off his loss of status once the Nazis acceded to power. Heart‐broken and ill, Haber died in Basel less than a year after being driven out of Germany.40

In his testament, Haber expressed his wish to be buried alongside his first wife Clara – in Dahlem if possible or elsewhere “if impossible or disagreeable.” Haber's son Hermann became the will's executor. In accordance with Haber's will, Clara's ashes were reburied beside his in Basel (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Gravestone of Fritz and Clara Haber at the Hörnli Cemetary in Basel.

6 Clara Haber's Suicide

The motive for Clara Haber's suicide is as unclear as the available sources are ambiguous – and rare (see Table 1). Much of the source material was generated nearly four decades after the suicide via interviews for the so called Jaenicke Collection, named so for Johannes Jaenicke, a Haber collaborator, who planned to write Haber's biography and who headed the forerunner of the Archive of the Max Planck Society. Mentions in memoirs and personal correspondence of people who knew the Habers provide additional tidbits, albeit sometimes only between the lines.

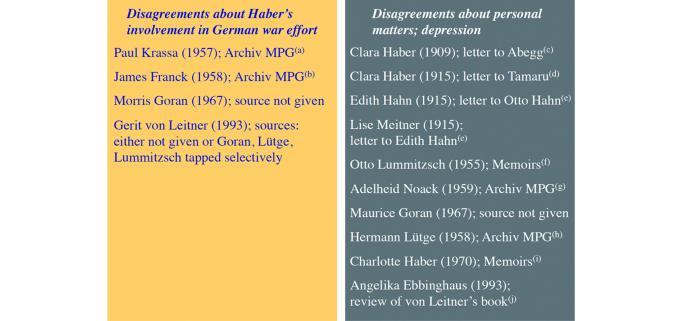

Table 1.

Possible motives for Clara Haber's suicide. Left: Sources suggesting that the motive had to do with disagreements about Haber's involvement in the German war effort. Right: Sources suggesting that Clara's suicide had to do with disagreements about personal matters and/or her depression. (a) Ref. 43; (b) Ref. 44; (c) Ref. 1; (d) Ref. 51; (e) Ref. 49; (f) Otto Lummitzsch, Erinnerungen, 1955, p. 2, Haber Collection Va Rep. 5, 1480, Archiv der Max Planck Gesellschaft; (g) Ref. 32; (h) Ref. 47; (i) Ref. 46; (j) Ref. 45.

|

|

However, there are also the accounts by Morris Goran41 from 1967 and a follow up by Gerit von Leitner42 from 1993 that could be – charitably – characterized as belletristic. In particular the latter captured the imagination of the public and achieved the status of a “canonical work” on Clara.

Morris Goran, in his book The Story of Fritz Haber, stated that Clara was “vitally affected” (p. 71) by her husband's involvement in WWI chemical warfare and committed suicide after a heated argument with Fritz about what she considered to be “a perversion of science” and “a sign of barbarism” (p. 71). Goran gives no evidence or sources for either this scenario or these statements. Apparently, the much‐quoted phrase about the perversion of science and barbarism, ascribed to Clara, is Goran's own. On the remainder of roughly three pages of his two‐hundred‐page Haber biography that he dedicated to Clara, Goran also points out that she was depressive and that (p. 71):

“… chemical warfare was an avenue or excuse for the morbid worry she seemed to favor.”

Although Goran doesn't give any references here either, most of the available sources suggest that Clara was indeed depressive and that the depressions that hit her in her later life had to do with her unhappy and unfulfilling married life on the side of Fritz Haber.

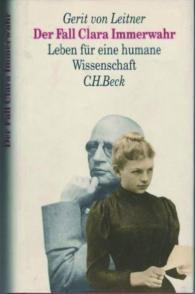

Goran's ill‐founded scenario about Clara's suicide as being connected with Fritz Haber's involvement in chemical warfare was appropriated and amplified by Gerit von Leitner in her widely read book Der Fall Clara Immerwahr. Leben für eine humane Wissenschaft (see Figure 8). In this book, Clara is presented as an outspoken pacifist (not unlike the 1905 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bertha von Suttner) and a star scientist (not unlike Marie Curie) who was destroyed – as both a person and a scientist – by her oppressive and opportunistic husband. The sources in von Leitner's book are either not given or tapped selectively, so as to provide a spotless image of Clara, while portraying Fritz Haber as a kind of Dr. Evil.

Figure 8.

Cover of Gerit von Leitner's book Der Fall Clara Immerwahr. Leben für eine humane Wissenschaft.

As listed in Table 1, a testimonial for the Jaenicke Collection about a possible role of chemical warfare in Clara's suicide was delivered by her cousin Paul Krassa, according to which Clara visited Krassa's wife shortly before the suicide to confide to her about the “gruesome effects” of chemical warfare that she had witnessed, in particular the “testing on animals.”43 Krassa, however, added that other factors may have been at play as well. Likewise, James Franck stated in his testimonial:44

“… that [Clara's] husband was involved in chemical warfare had surely an effect in her suicide.”

However, Franck added that Fritz Haber:

“… expended immense effort to reconcile his and [Clara's] political and human views.”

Von Leitner's account only refers to the first parts of these two testimonials and ignores other sources that suggest that the reasons for Clara's suicide may have had to do with her private life. These testimonials or opinions are listed on the right in Table 1.

Clara's much‐cited 1909 letter to Richard Abegg1 is a case in point. Written on funeral stationary and opening with a tirade about her inability to locate a fountain pen (described – in pencil – on two pages out of twelve), Clara denounces her husband and details her unfulfilling life with him. The letter may have been triggered by jealousy, after Abegg, during his visit to Karlsruhe, congratulated Fritz Haber on his discovery of the catalytic synthesis of ammonia without mentioning Clara.45 Clara, however, had not been involved in research – her own or Haber's – since about 1901, as she had acknowledged in the same letter. The letter is special in that it is the only one written by Clara to Abegg (or anybody else for that matter) where she lost her nerve and complained about Haber and their marriage. Given the magnitude of the Fritz Haber calumny, we would have expected to find a long series of such letters…

Out of the rest of the testimonials on the right of Table 1 we would like to bring to the fore those provided by the niece, Adelheid Noack, of Clara's brother‐in‐law, and of the institute mechanic, Hermann Lütge. Adelheid Noack stated32 that Clara was “horrified by anything sensual,” in keeping with the fact that she had quit the marital bedroom in 1902, never to return to it. This fact as well as Noack's testimonial was corroborated by Haber's second wife, Charlotte Nathan, who had access to such intimate information more than anybody else.46 A real bombshell was dropped by Hermann Lütge, who testified that during the fateful night of May 1–2, 1915, Clara found her husband in flagranti with Charlotte Nathan.47 Charlotte worked as a manager of the then incipient club Deutsche Gesellschaft 1914, where she and Haber got to know each other and was invited to the grand celebration of the “success” at Ypres in Habers' mansion (although Charlotte later contradicted it). The sociologist Angelika Ebbinghaus45 as well as the historian Margit Szöllösi‐Janze48 indicated that they tend to the view that Clara's discovery of her husband's affair may have been the actual trigger for her suicide. This is indirectly corroborated by the yet unpublished letters of Edith Hahn to her husband Otto and of Lise Meitner to Edith Hahn.49 Sadly, these letters indicate that Clara was perceived as a person out of place in Dahlem, known to have complained about being neglected by her husband.

Two more traumatic events in Clara's life should be mentioned as possible reasons for her depressed state: Richard Abegg's death in a ballooning accident, in 1910, and Otto Sackur's death, in 1914, in a laboratory accident. While Abegg represented Clara's connection to science and, in addition, acted as her “cheer‐leader” and confidant in private matters, Otto Sackur was Clara's friend and Kommilitone from Breslau. He died as a consequence of a laboratory accident in front of Clara's eyes. Among the first to attend to the injured, Clara proved capable of acting rationally in a situation drastic to the extreme and to coordinate attempts to help the injured. Fritz Haber was just gasping for air in the arms of a co‐worker.

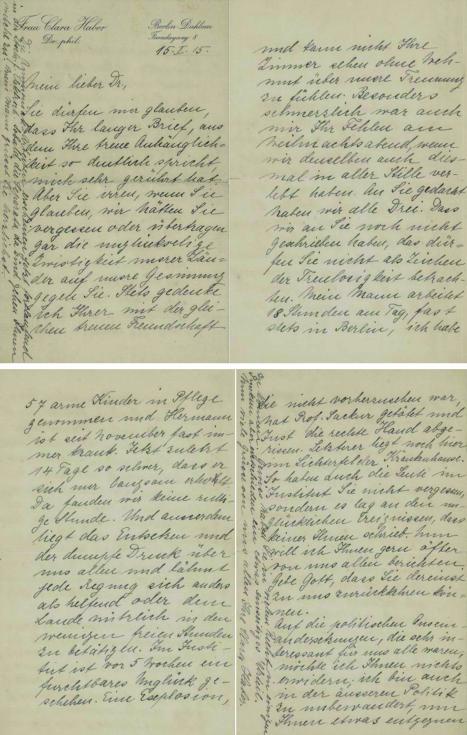

A brief description of Sackur's accident is available in Clara's own hand, namely in her reply to a letter from Haber's former Japanese collaborator, Setsuro Tamaru, who had to leave Germany after the outbreak of the war and who complained bitterly in his letter about the war's politics.50 Clara's reply,51 from January 15, 1915 (see Figure 9), is revealing in several respects: Firstly, she describes her own patriotic feeling and a need to be “helpful” and “useful” to her country; Secondly, she mentions that her husband was working “18 hour days” and that she herself was taking care of “57 poor children” (apparently children whose fathers were on the front), while her son Hermann had been “constantly sick since November.” Thirdly, she glosses over Tamaru's litany about the political situation and describes herself as:

Figure 9.

Letter from Clara Haber to Setsuro Tamaru, dated 15 January, 1915. Upper panel: pages 1 and 2; lower panel: pages 3 and 4.

“… too ignorant in the matters of foreign affairs to be able to properly reply …”

to it. All in all, Clara's letter to Tamaru is difficult to reconcile with her image as an outspoken pacifist whose disagreements with her husband about the conduct of the war would drive her to suicide. Instead, what transpires are her concerns about how the war had affected her personal life rather than the world order or any bigger issues – except for a sense of obligation to help one's country that she had expressed quite clearly.

Moreover, there are testimonials suggesting that Clara in fact approved of the activities of her husband in the war. Dr. Kremmer, the principal of Hermann Haber's school, described in his condolence letter52 to Hermann upon the death of Fritz Haber in 1934 how Herrmann's “Frau Mutter” came to him “to report on the success of the first gas attack at Ypres right after receiving a telegram” from the front about it. And Hermann Lütge, in his testimonial for the Jaenicke Collection,53 stated that Clara “was simply not in a state of mind that would allow her to contemplate the reprehensibility of the gas war. The boss [i.e., Clara] was proud of the services provided by her husband.”

In summary, Clara Haber's suicide appears to have had much more complex causes than usually acknowledged. It had likely been the result of a “catastrophic failure” (to borrow an engineering term as a metaphor) brought about by a most unfortunate confluence of a host of circumstances that included, apart from her unfulfilling life, Haber's philandering, the tragic deaths of her closest friends, Richard Abegg and Otto Sackur, as well as the death and destruction of the war itself.

7 Clara Haber's Legacy

Those familiar with the name Clara Immerwahr have surely noticed that our account, especially of the motive for her suicide, differs considerably from the image that has become prevalent in the public domain over the last two decades.

This image is particularly trenchant in Gerit von Leitner's 1993 book, Der Fall Clara Immerwahr. Leben für eine humane Wissenschaft (Figure 8). In this book, Clara's life and suicide are presented as a “beacon against weapons of mass destruction and for a humane science” and bolstered by numerous quotations, which are, however, hard to verify, please see Appendix. This had been already pointed out in a number of reviews54 shortly after the book's publication, but to no avail, as the book became widely read and has determined to this day the public image of Clara. Apparently, the book struck a chord with the Zeitgeist and has served as a vehicle for furthering the opinions and ideals of the peace movement, feminism, and antimilitarism. The book constructed a Wunschbild. Clara's attempt to have a self‐determined life as a woman, mother, and scientist as well as her tragic suicide are interpreted as a “[beacon of a] feminine, life‐preserving science” and juxtaposed with the male, patriarchal power‐oriented science concerned with the exploitation of resources. Although von Leitner's book as well as its numerous derivatives force such an interpretation on us, the available scholarly sources in no way support it. Especially Clara's tragic suicide was likely a consequence of a long period of alienation between the spouses and cannot be connected solely with Haber's career‐oriented mentality and his engagement in chemical warfare. Moreover, Haber had something to show for his workaholism – and Clara, like anybody familiar with Haber's work, must have been well aware of it. The discovery of the catalytic synthesis of ammonia is but one of many of Haber's achievements, albeit perhaps the most significant among those that “have conferred a benefit to mankind.”

Our intention has been to make the above points without belittling in the least Clara's achievements and courage. Honoring Clara, for instance through the Clara Immerwahr Award of the Nobel‐Prize winning organization International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) or the Clara Immerwahr Award of the Berlin Excellence Cluster UniCat, is highly to the point and should not be questioned in any way. Haber's institute, named after its founding director in 1952 and incorporated into the Max Planck Society in 1953, had a memorial built for Clara in the garden of the institute in 2006 (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Memorial for Clara Haber in the garden of the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society, installed in 2006. The photo shows the memorial at the centenary of Clara's suicide, on May 2, 2015.

However, we should refrain from projecting our contemporary ideas about women's rights activists or peace activists on Clara Haber in an ahistorical way. What she achieved in her time does not need to be embellished with exaggerations or even wishful thinking fashioned by present‐day aspirations.

Clara's admirable feat of graduating in chemistry with magna cum laude in a 1900 Prussia was not only unusual but also difficult, or unusual because it was difficult. It took the first thirty years of her life to achieve it, for she was denied a straight path, free of hurdles and chicanes, and had to take lengthy detours. Nowadays, many leading universities attained parity in the numbers of male and female students. And there are many female scientists as a result, although there could be more, especially in the hard sciences – as well as in the leading positions in academia and other walks of life. It is worth remembering that Clara's case helped to achieve it. Better still, it is worth to remember Clara and help to achieve the rest.

8 Appendix

A partial list of statements and quotations appearing in accounts of Clara Haber's relation to chemical warfare that are of unknown origin:

In the list below, Goran stands for Ref. 41; 75 Jahre FHI stands for Gerd Chmiel, Uli Hansmann, Hans‐Joachim Krauß, Bärbel Lehmann, Herbert Mehrtens, Wolfgang Ranke, Bernhard Smandek, Norbert Sorg, Manfred Swoboda, E. Wurzenrainer: “…im Frieden der Menschheit, im Kriege dem Vaterlande…”, 75 Jahre Fritz‐Haber‐Institut der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaft. Bemerkungen zur Geschichte und Gegenwart, 1986, Berlin; von Leitner stands for Ref. 42.

She began to regard poison gas not only as a perversion of science but also as a sign of barbarism. It degraded and corrupted the discipline, which had opened new vistas of life. (Goran, p. 71)

Clara forderte ihn ultimativ auf, das Unternehmen abzubrechen, und drohte mit ihrem Freitod. (75 Jahre FHI, p. 27)

Clara bewunderte die österreichische Pazifistin und Schriftstellerin Bertha von Suttner. (von Leitner, p. 48)

Auch Philipp Immerwahr [father of Clara] hat sich aufgeregt, dass die Gründung des Breslauer Mädchengymnasiums im April 1898 trotz breiter Unterstützung wieder abgelehnt worden ist. Die Begründung in der Zeitung hat Clara dick rot angestrichen… (von Leitner, p. 51)

Diskussionen zwischen Fritz und Clara zur Frauenfrage (von Leitner, p. 167)

Als Clara sich über die diffamierenden Article [about Marie Curie and Paul Langevin] empörte, meinte Fritz [Haber], die Radiumforschung sei eben eine revolutionäre Wissenschaft und das erzeuge Neid… Ihm ist das Ganze schon allein als Komplott gegen die amtliche Stellung der vielbeneideten Frau Professor als Lehrkraft an der Sorbonne verständlich. (von Leitner, p. 174)

Für Clara ist es [WWI] ein Sturz ins Dunkle, bei dem alle Fundamente des Lebens erschüttert warden … Clara spürt den Klagelaut jeder einzelnen Frau, erstickt unter den Gesetzen. (von Leitner, p. 186)

“Die Allmacht der Wissenschaftler ist oft nur Bluff,” tröstet Clara. (von Leitner, p. 191)

Er beginnt in seinem Institut mit Laborversuchen an Tieren. Clara ist wie gelähmt. Welch ein Zeichen der Barbarei.. “Wenn du wirklich ein glücklicher Mensch wärst, dann könntest du das nicht machen“ Fritz hat ihr strengste Geheimhaltung nach außen auferlegt. Wie kann sie schweigen, wenn es um die Bedrohung des Lebens geht? ... Mit Zinaide Krassa kann sie sprechen … Als Clara weinend von der Begasung der Tiere in den Versuchsöfen im Institut erzählt, von der unvorstellbaren Akribie, mit der die Vernichtung wissenschaftlich erprobt und am Seziertisch begutachtet wird, ohne dass moralische Bedenken auch nur aufzutauchen scheinen, wird sie in ihrem Vorhaben bestärkt, ihre Mittäterschaft zu verweigern. (von Leitner pp. 196–197)

(Original, Krassa to Jaenicke, 2 November 1957: “Sie war verzweifelt über die grauenhaften Folgen des Gaskriegs, dessen Vorbereitung und Prüfung an Tieren sie mit angesehen hatte.”)

Clara kann dieser Argumentation der Frauenvereine nicht folgen. Der maßgeblichen Beteiligung von Fritz an einer chemischen Massenvernichtung kann sie nicht tatenlos zusehen … es ist ihre Aufgabe und Pflicht, jeden Menschen, der nur einen gewissen Einblick in die heutige Technik besitzt, darauf hinzuweisen, dass sowohl die Art als auch die Menge der chemischen Vernichtungsmittel ganz andersartig ist und eine prinzipielle Änderung der Gefahr mit sich bringt … Fritz wirft ihr vor, nur aus idealistischen Motiven gegen den Krieg wirken zu wollen … Sie stünde zu weit außerhalb des wirklichen Lebens.” (von Leitner, p. 199)

[About the visit at the proving ground in Köln‐Wahn:] Sie halten Clara für schmückendes Beiwerk, begegnen ihr mit Galanterien und nehmen es kaum zur Kenntnis, wenn sie ihre Ablehnung der chemischen Waffe äußert. (von Leitner, p. 201)

Wie ein Schlag ins Gesicht trifft es sie, als er [Fritz] ihr [Clara] an diesem Abend vorwirft, ihm und Deutschland in der größten Not und Hilflosigkeit in den Rücken zu fallen. (von Leitner, p. 215)

Acknowledgements

We owe our thanks to Dr. Christoph Israng, German Ambassador to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in The Hague, for inviting us to give a presentation at the Permanent Representation of Germany to the OPCW on November 26, 2015. Our talk became the basis for the account presented herein. Our special thanks are due to Prof. Margit Szöllösi‐Janze (Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität, München), whose authoritative biography Fritz Haber: 1868–1934 (C.H. Beck, München, 1998) that covers both Fritz and Clara Haber, proved to be an invaluable source of scholarship on the subject. In addition, Prof. Szöllösi‐Janze kindly provided comments specific to this article. We also thank Prof. Eckart Henning (former director of the Archive of the Max Planck Society, Berlin) for introducing us to the unpublished 1915 letters by Edith Hahn and Lise Meitner that mention Clara's suicide. We are also grateful to Prof. Hideko Tamaru Oyama (Rikkyo University) for making available to us the letter by her grandfather Setsuro Tamaru to Clara from December 24, 1914. Last but not least, we thank Gerhard Ertl (Fritz Haber Institute), Hajo Freund (Fritz Haber Institute), Dudley Herschbach (Harvard University) and Matthew Meselson (Harvard University) for a critical reading of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Bretislav Friedrich, Email: brich@fhi-berlin.mpg.de.

Dieter Hoffmann, Email: dh@mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de.

References

- 1. Clara Haber to Richard Abegg, 23 April 1909, Haber Collection, Archiv der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaf.

- 2. Szöllösi‐Janze M. , Fritz Haber (1868–1934). Eine Biographie, 1998. , Beck C. H. , München, pp. 124 –131 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goethe, the Story of a Man: Being the Life of Johann Wolfgang Goethe as Told in His Own Words and the Words of His Contemporaries, Volume 1, 1949. , Farrar, Straus, p. 378 [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Rahden T. , Jews and Other Germans: Civil Society, Religious Diversity, and Urban Politics in Breslau 1860–1925, 2008. , University of Wisconsin Press, p. 32 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scheuermann G. , Das Breslauer Lexikon,, 1994. , Laumann‐Verlag Dülmen [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark C. , Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947, 2007. , Penguin [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson J. , NTM Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin 1998. , 6 , 1 –21 . [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ref. [2] p. 124.

- 9. Ref. [2] p. 124.

- 10. Ref. [2] p. 125.

- 11. Max Planck as quoted in Das Geschlecht der Bildung – Die Bildung der Geschlechter (Eds. B. L. Behm , G. Heinrichs, H. Tiedemann), Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1999, p. 101 .

- 12. Ref. [2] pp. 126–127.

- 13. Ref. [2] p. 128.

- 14. Arrhenius S. , Z. Elektrochem. 1910. , 16 , 554 –557 . [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nernst W. , Chem. Ber. 1913. , 46 , 619 –628 . [Google Scholar]

- 16. B. Friedrich, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201509260.

- 17. Ostwald W. , Z. Phys. Chem. 1887. , 1 , 1 –4 . [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abegg's main contributions to physical chemistry include (1) investigations of osmotic pressure, especially at extreme concentrations; (2) dielectric constants, in particular in relation to phase transitions; (3) electrochemistry, especially the determination of ion mobility in electrolytic solutions; (4) chemical equilibria, particularly of tautomerization processes; (5) studies of electro‐affinity, an electrochemically defined concept introduced by Abegg and Bodländer that was supposed to provide a bridge between chemical affinity and electrochemical behavior; (6) and last but not least, Abegg contributed to the development of the notion of chemical valence through work that gave rise to the octet rule.

- 19. Badino M. , Dissolving the Boundaries between Research and Pedagogy: Otto Sackur's Lehrbuch der Thermochemie und Thermodynamik, in Research and Pedagogy, (Eds.Badino M., Navarro J.), Edition Open Access, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abegg R. , Sackur O. , Physikalisch‐chemische Rechenaufgaben, 1909. , Sammlung Göschen [Google Scholar]

- 21. Badino M. , Friedrich B. , Phys. Perspect. 2013. , 15 , 295 –319 . [Google Scholar]

- 22. Immerwahr C. , Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie, Stöchiometrie und Verwandtschaftslehre 1900. , 32 , 142 –144 . [Google Scholar]

- 23. Immerwahr C. , Z. Anorg. Chem. 1900. , 24 , 269 –278 . [Google Scholar]

- 24. Immerwahr C. , Z. Elektrochem. 1901. , 7 , 477 –483 . [Google Scholar]

- 25. Immerwahr C. , Z. Anorg. Chem. 1900. , 24 , 112 –112 . [Google Scholar]

- 26. Immerwahr C. , Z. Elektrochem. 1901. , 625 –625 . [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abegg R. , Bodländer G. , Z. Anorg. Chem. 1899. , 20 , 453 . [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ref. [2] p. 129

- 29. Cf. footnote 165 on p. 735 of ref. [2].

- 30. Haber F. , Thermodynamics of Technical Gas Reactions, 1908. , Longmans, Green & Co, London [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clara Haber to Richard Abegg, 18 October 1901, Haber Sammlung Va Rep. 5, 812, Archiv der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaft.

- 32. A. Noack, Recollection from 19 November 1959, Haber Sammlung Va Rep. 5, 301, Archiv der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaft.

- 33. Stern F. , Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012. , 51 , 50 –56 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dunikowska M. , Turko L. , Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011. , 50 , 10050 –10062 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smil V. , Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production, 2000. , MIT Press, Cambridge, MA [Google Scholar]

- 36. See, e.g., Gerd Hardach, The First Wolrd War 1914–1918, 1977. , University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 59 –60 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haber F. , Fünf Vorträge aus den Jahren 1920–1923, 1924. , Springer, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ref. [2] p. 267 and pp. 330–332.

- 39. James J. , Steinhauser T. , Hoffmann D. , Friedrich B. , One Hundred Years at the Intersection of Chemistry and Physics, 2011. , De Gruyter, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stern R. , Fritz Haber. Personal Recollections, 1963. , Leo Beck Instititute, London [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goran M. , The Story of Fritz Haber, 1967. , University of Oklahoma Press, Norman [Google Scholar]

- 42. von Leitner G. , Der Fall Clara Immerwahr. Leben für eine humane Wissenschaft, 1993. , Beck C. H. , München [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paul Krassa to Johannes Jaenicke, 2 November 1957, Haber Sammlung Va Rep. 5, 1470, Archiv der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaft.

- 44. Johannes Jaenicke, a note from his conversation with James Franck on 16–17 April 1958, Haber Sammlung Va Rep. 5, 1449, Archiv der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaft.

- 45. Ebbinghaus A. , Zeitschrift für Sozialgeschichte des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts 1993. , 8 , 125 –131 . [Google Scholar]

- 46. Charlotte Haber, Mein Leben mit Fritz Haber, 1970. , Econ‐Verlag, p. 83 and 89 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hermann Lütge to Johannes Jaenicke, 9 and 17 January 1958, Haber Sammlung Va Rep. 5, 260, Archiv der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaft.

- 48. Ref. [2] p. 398.

- 49. E. Henning, Freitod in Dahlem (1915). Unveröffentlichte Briefe von Edith Hahn und Lise Meitner über Dr. Clara Haber geb. Immerwahr, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2016, DOI: 10.1002/zaac.201600052 .

- 50. Setsuro Tamaru to Clara Haber, 24 December 1914. Courtesy of Hideko Tamaru Oyama, Tokyo, Japan.

- 51. Clara Haber to Setsuro Tamaru, 15 January 1915; see also; Tamaru Oyama H. , Chem. Rec. 2015. , 15 , 535 –549 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dr. Kremmer to Hermann Haber, 2 February 1934. Haber Sammlung Va Rep. 5, 1222, Archiv der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaft.

- 53. Hermann Lütge to Johannes Jaenicke, 17 January 1958, Haber Sammlung Va Rep. 5, 260, Archiv der Max‐Planck‐Gesellschaft.

- 54. In particular Ref. [2] pp. 393–399, and Ref. [43].