Abstract

Cell division is a metabolically demanding process, requiring the production of large amounts of energy and biomass. Not surprisingly therefore, a cell's decision to initiate division is co-determined by its metabolic status and the availability of nutrients. Emerging evidence reveals that metabolism is not only undergoing substantial changes during the cell cycle, but it is becoming equally clear that metabolism regulates cell cycle progression. Here, we overview the emerging role of those metabolic pathways that have been best characterized to change during or influence cell cycle progression. We then studied how Notch signaling, a key angiogenic pathway that inhibits endothelial cell (EC) proliferation, controls EC metabolism (glycolysis) during the cell cycle.

Keywords: angiogenesis, cell cycle, endothelial cell, metabolism, quiescence

Introduction

Cell proliferation is an energetically demanding process that requires the generation of large amounts of new proteins, lipids and nucleic acids. Not surprisingly therefore, a cell's decision to enter the cell cycle and to undergo duplication represents a formidable commitment that can only be successful when sufficient nutrients are available.1 Several non-proliferating cells secure their metabolic needs by preferentially using mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).2 In contrast, proliferating cells often have high rates of glycolysis and produce abundant glycolytic intermediates for the biosynthesis of macromolecules in the pentose phosphate and serine biosynthesis pathway.3 In addition to utilizing "aerobic glycolysis”, proliferating cells also use glutamine as fuel for the synthesis of biomass.

Cell division in mammals occurs in distinct phases: the G1 and G2 phase when cells grow and synthesize new biomass, the S phase during which DNA is replicated, and the M phase when cells undergo mitosis, followed by cytokinesis. Cells can also exit the cell cycle by becoming quiescent and enter the G0 phase. For cell division to proceed, the different metabolic pathways must be temporally coordinated so that sufficient energy and nutrients are available for biomass synthesis.4 This explains the bidirectional crosstalk between the cell cycle and cellular metabolism.

Metabolic control of the cell cycle

Regulation of cell proliferation by metabolism evolved in part to cope with nutritional deprivation, explaining why mechanisms arose to reduce cell growth and arrest cell cycle progression in conditions of starvation.5 A key regulatory step early in the G1 phase of the cell cycle is the growth factor-dependent restriction point, when cells commit to mitosis in the presence of growth factors or conversely, in the absence of growth signals, exit the cell cycle and enter the G0 phase.6 During mid-to-late G1, a nutrient-sensitive cell growth checkpoint controls progression to S phase, and enables the cell to complete cell division, but only when sufficient nutrients are available.6,7 Indeed, the cell must prepare for division in G1 by synthesising macromolecules, needed for biomass duplication. Mitotically committed cells thus transiently upregulate the glycolytic activator 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) at the nutrient-sensitive checkpoint (Fig. 1A), and blocking glycolysis or reducing glucose availability impairs the passage through this restriction point.8,9 Glutamine breakdown is also essential for progression to S-phase but unlike PFKFB3, it is also needed for the progression from the S to G2-M phase, which is reflected by the high activity of glutaminase1 (GLS1), a rate-limiting enzyme of glutaminolysis, in these phases of the cell cycle (Fig. 1A).10 Whether this relates to the use of glutamine for the production of biomass, redox homeostasis and/or energy requires further study.11 Furthermore, there is increasing insight in the role of mitochondria in cell cycle progression. Recent evidence suggests that mitochondrial dynamics and morphology are coordinated with cell cycle progression. Indeed, at G1/S, mitochondria fuse with each other to form an interconnected network, while they become fragmented at G2/M.12 Mitochondrial fission enables distribution of functional mitochondria and mitochondrial genome (mtDNA), which encodes subunits of complex I, III, IV and V for OXPHOS, between mother and daughter cells.13,14 In addition, mitophagy eliminates damaged mitochondria after fission.12 Also, daughter cells that receive fewer old mitochondria maintain stem cell traits.15

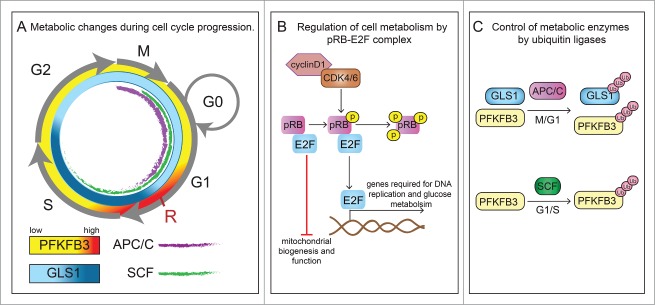

Figure 1.

Crosstalk between cell cycle regulators and cellular metabolism. (A) Transitions between phases of the cell cycle (G1, S, G2 and M) are orchestrated by cell cycle activators and inhibitors. In particular, the transition from G1 to the S-phase is of high importance for the regulation of proliferation and is controlled by cyclins (cyclinD), cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes, E2F family of transcription factors and the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) family members and E3 ubiquitin ligases (see panels B and C). At late G1, a nutrient-sensitive cell growth checkpoint (labeled as R) controls progression to S phase, and enables the cell to complete cell division, but only when sufficient nutrients are available. The glycolytic activator 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) is transiently upregulated at this checkpoint (symbolized by higher intensity red color). Similarly, glutaminolysis is also critical for G1-to-S transition and in addition is also important for S to G2-M progression (symbolized by higher intensity blue color reflecting glutaminase1 (GLS1) activity). Furthermore, anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) (purple) and Skp1/Cullin/F-box (SCF) (green) control the activities of PFKFB3 and GLS1 during the different stages of the cell cycle. (B) In response to mitogens, signaling pathway kinases convey proliferative signals to activate expression of cyclins. Enzymatically active complexes of cyclins and CDKs sequentially phosphorylate pRB family members. Binding of non-phosphorylated pRb to E2F prevents the transition from G1 to S-phase, induces cell quiescence and represses expression of genes involved in mitochondria biogenesis and function. However, phosphorylation of pRB releases its binding from E2F and thus inhibitory function and allows entry into S-phase. Activation of E2F not only leads to transcription of genes involved in cell cycle progression (e.g., cyclin E) but also enzymes involved in glucose metabolism (PFKFB). (C) Further crosstalk from the cell cycle back to metabolism is exemplified by the observation that APC/C, which is active during the M and G1 phase (indicated in the cell cycle scheme in panel A by a purple inner line) promotes the proteasomal degradation of PFKFB3 and glutaminase 1 (GLS1), while the ubiquitin ligase SCF, active during G1 and S phase (indicated in the cell cycle scheme in panel A by a green inner line), targets only PFKFB3.

Lipids play an indispensable role in processes like cell differentiation or organ morphogenesis, and are intimately associated with cell cycle progression. Apart from being a component of cell membranes, lipids are also mediators of signaling pathways, e.g. by affecting membrane proteins or multiprotein complex assembly. Several studies pointed to the fluctuations of different classes of lipids during cell cycle progression. For instance, in macrophages, the G1 phase is characterized by rapid phospholipid turnover, but during G2/M, phospholipid metabolism ceases.16 In line with these findings, the regulation of the lipidome is tightly synchronized with the cell cycle.17 Silencing of lipid biosynthetic enzymes (including sphyngomyelin phospodiesterase 4, galactosylceramidase, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2) leads to cell division defects and cytoskeletal changes in interphase cells.17 Moreover, inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis results in cell cycle arrest in G0.18 In addition, the lipid bilayers of the nuclear envelope and the plasma membrane display different mechanical properties depending on the stage of cell cycle, presumably to adapt to the mechanical stress during cell division.17

Many genetic changes that promote cancer involve a dysregulation of cell cyle progression at G1/S. However, the metabolic changes regulating progression through the G1 restriction points in healthy cell types remain poorly defined. In the next sections, we provide an overview of the crosstalk between molecular regulators of the cell cycle and cell metabolism, and vice versa. We also explored whether Notch, a critical regulator of endothelial cell (EC) growth and vessel sprouting,19 controls cell cycle progression by influencing metabolism (glycolysis) in ECs. ECs lining the lumen of blood vessels are a prototypical example of a cell type, able to switch plastically back and forward between quiescence and proliferation, but a regulation of cell cycle progression by metabolism in ECs remains unknown. Rather than attempting to provide an exhaustive survey of all available literature, we will explain principles by illustrating examples.

Cell cycle regulators control cellular metabolism

Adequate transition from the G1 to S phase is crucial for the control of cell proliferation. Cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), E2F family of transcription factors (E2F1–6) and the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) family members (including pRB, p130, p107) are key regulators of cell cycle progression. In early G1, family members of pRB bind to and inactivate the E2F family of transcription factors. By upregulating the expression of cyclins (cyclin D, cyclin E), mitogenic signals (e.g., growth factors) promote the assembly of enzymatically active complexes of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) such as cyclin D/CDK4/CDK6 and cyclin E/CDK2, which sequentially phosphorylate pRB family members and thereby favor dissociation of the pRB/E2F complex. Hyperphosphorylated pRB family members no longer bind to E2F, allowing E2F-mediated transcription of genes that are required for S-phase progression and DNA synthesis.20,21 Recent publications have shed light on the involvement of the CDK/pRB/E2F pathway in the regulation and orchestration of the metabolic changes occurring during cell cycle progression.

Notably, specific E2Fs can function either as activators or repressors of transcription, thus cell cycle regulators can have a dual role in modulation of metabolic function. Many proliferating cells induce glycolytic rates. These proliferating cells have increased active E2F levels, and an E2F-binding site has been identified in the promoter of a 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFKFB) isoenzyme,22,23 an activator of glycolysis. A genome-wide study revealed that the pRB/E2F complex downregulates the expression of genes, involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and function and that loss of E2F4 releases the repressive state of these genes (e.g., genes encoding different subunits for cytochrome c or ferredoxin reductase).24,25 In addition, the pRB/E2F1 complex has been shown to suppress oxidative metabolism and E2F1 deficient mice exhibit an oxidative phenotype.26 In addition, the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial function is increased in adipose specific pRB knock-out mice, implying that pRB represses mitochondrial activity (Fig. 1B).27 E2F1 also blunts glucose oxidation by suppressing the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA via upregulating the expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK4), an enzyme that controls the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH).28 In line with this observation, loss of E2F1 decreases expression of PDK4 and enhances glucose oxidation.26

Cyclin and CDK enzymes have been also implicated in the regulation of cell metabolism. Indeed, D-type cyclins, which are induced as soon as the cell enters G1, regulate the metabolic machinery. However, their effect on cell metabolism remains in part enigmatic and contextual. In cancer cells, overexpression of cyclin D1 downregulates the expression of hexokinase II (HKII), a rate-limiting glycolytic enzyme, and reduces mitochondrial activity, while silencing of cyclin D1 causes opposite effects,29 together suggesting that cyclin D1 inhibits glycolysis. This activity of cyclin D1 seems counterintuitive with respect to its role in cell proliferation and the increased glycolytic rate in proliferating cells. However, this study only determined the expression of glycolytic genes, without measuring glycolytic flux. On the other hand, in malignant tumors, HKII binds to the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), the most abundant outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) protein, which mediates the trafficking of metabolites across the OMM.30-32 This interaction allows direct access by HKII to ATP generated by mitochondrial ATP synthase, thereby accelerating phosphorylation of glucose and subsequent funneling of glucose-6-phosphate along the glycolytic pathway; in agreement, pharmacological disruption of the HKII-VDAC interaction inhibits glycolysis.30–33 Of note, cyclin D1 was reported to compete with HKII for binding to VDAC,30 which could negatively affect glycolysis. However, as none of the above cyclin D1 studies directly measured glycolytic flux, the precise effect of cyclin D1 on glycolysis in cancer cells remains unknown. Also, the HKII interaction with VDAC has only been documented in cancer cells to date.30,33 Whether and how cyclin D1 regulates glycolysis in non-malignant cells and has similar context-dependent effects remains unresolved to date.

Ubiquitin ligases regulate metabolism during the cell cycle

Regulation of cellular metabolism by the cell cycle also occurs at another level. Indeed, the ubiquitin proteasome pathway regulates the levels of various metabolic enzymes during cell cycle progression. Two E3 ubiquitin complexes, anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and Skp1/Cullin/F-box (SCF), control ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation of cyclins and key metabolic enzymes in order to coordinate cell cycle progression with metabolic needs for cell proliferation. APC/C is active during the G1 and M phase, while SCF shows activity during mitosis, G1 and S phase (Fig. 1A).34 Several studies demonstrated that the ubiquitin proteasome pathway regulates the supply of metabolic substrates during cell cycle progression. For instance, the APC/CCdh1 complex promotes degradation of key enzymes of glycolysis (PFKFB3) and glutaminolysis (glutaminase 1; GLS1), while the SCFβTrCP complex targets PFKFB3 for degradation8-10 (Fig. 1C). Late in G1, a decrease in APC/CCdh1 activity results in a surge of PFKFB3 and GLS1; this elevates glycolysis and glutaminolysis, which provide carbons and nitrogen for the synthesis of building blocks required for cell division.9,10 Furthermore, by degrading PFKFB3, SCFβTrCP decreases glycolysis during the S phase. These divergent posttranslational regulations of PFKFB3 and GLS1 point to a different role for glucose and glutamine at distinct stages in the cell cycle.

Signaling by metabolic enzymes controls cell cycle progression

Several metabolic enzymes regulate cell cycle progression through a metabolism-independent activity. We will illustrate this with some examples. For instance, the muscle-specific pyruvate kinase isoenzyme PKM has both metabolic and metabolism-independent activity. PKM regulates the final step of glycolysis by catalyzing the transfer of a phosphate group from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to ADP to produce pyruvate and ATP. The alternatively spliced isoform PKM1 is expressed in cells with a high ATP demand, while PKM2 is detected in proliferating cells and cancer cells.35,36 Unlike PKM1, which exists in an active tetrameric form, PKM2 can be expressed either as an active tetramer or as a dimer with low affinity for PEP. In its highly active tetrameric conformation, PKM2 drives high yield ATP synthesis, whereas in its less active dimeric conformation, PKM2 constitutes a metabolic bottleneck, allowing build-up of glycolytic intermediates, which become redirected toward biosynthesis, fueling for instance the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) for DNA synthesis.36 Moreover, in tumor cells, a decrease in PKM2 activity results in the accumulation of upstream glycolytic intermediates, which generate reducing potential for ROS scavenging in the PPP.37 However, selective loss of PKM2 in fibroblasts, resulting in an upregulation of PKM1, decreases de novo nucleotide biosynthesis and inhibits cell cycle progression.38

PKM2 has been also involved in metabolism-independent cellular functions (Fig. 2A, B). For instance, upon mitogenic and oncogenic stimulation (for instance by EGFR activation), PKM2, but not PKM1, translocates to the nucleus,39 where it acts as a protein kinase to phosphorylate histone H3 at H3-T11. This leads to the release of histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) from regulatory DNA sequences and subsequent histone H3-K9 acetylation.40 PKM2-dependent histone H3 modifications are essential for the induction of cyclin D1 expression. These findings thus reveal a role for PKM2 in the epigenetic regulation of the transcription of genes, important for G1-to-S transition40 (Fig. 2A). Nuclear PKM2 also interacts with c-Src-phosphorylated β-catenin and enhances the transactivation activity of β-catenin. The interaction between PKM2 and β-catenin is required for this complex to interact with transcription factor 4 (TCF4) and to bind to β-catenin target genes like CCND1 (encoding cyclin D1) and MYC41 (Fig. 2B). PKM2 also phosphorylates and activates ERK1/2, which is crucial for cell proliferation.42

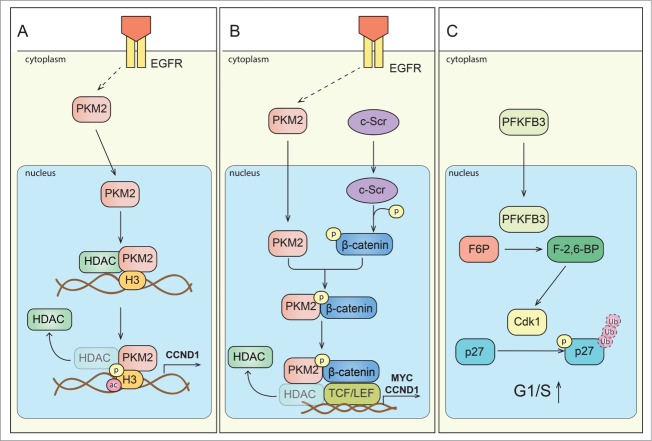

Figure 2.

Signaling of metabolic enzymes controls cell cycle progression. (A) Scheme depicting direct interaction of PKM2 and histone H3. Upon activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), PKM2 translocates to the nucleus. PKM2 directly interacts with histone H3 and subsequently can phosphorylate it (P) at H3-T11, which leads to histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) removal from the promoter region of a.o. CCND1 (encoding cyclin D1 expression), histone H3-K9 acetylation (ac) and cyclin D1/Myc transcription. Expression of these genes is critical for G1/S phase transition. (B) Scheme depicting regulation of gene expression by PKM2 mediated β-catenin transactivation. Upon EGFR activation, PKM2 translocate to the nucleus, where it binds to c-Src-mediated phosphorylated β-catenin. Phosphorylated (P) β-catenin binds PKM2, and this interaction allows the protein complex to interact with transcription factor 4 (TCF4), and to bind to the promoter of target genes (CCND1, MYC) resulting in the dissociation of HDAC3 and activation of gene transcription. (C) Proposed scheme of PFKFB3 mediated effects on cell cycle regulators. PFKFB3 (splice variant 5) can localize to the nucleus, where its product, Fru-2,6-BP, activates cyclin-dependent kinase-1 (CDK1). CDK1-mediated phosphorylation (P) of p27, would then lead to p-p27 ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. These changes lead to acceleration of cell cycle progression at G1/S.

Another glycolytic enzyme, PFKFB3, promotes cell proliferation, in part by stimulating glycolytic ATP production, but also by modulating the expression of cell cycle regulators. Indeed, overexpression of PFKFB3 upregulates the expression of cyclin D3 and CDK1, while downregulating the expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p27.43 These changes enable cells to overcome rate-limiting steps in cell division, such as the G1/S restriction point. Fructose-2,6-biphosphate (Fru-2,6-BP), a product of PFKFB3, is not only a potent allosteric activator of phosphofructokinase-1 (a rate limiting enzyme of glycolysis), but also promotes phosphorylation of p27 by allosteric activation of the kinase CDK1, likely leading to its ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation (Fig. 2C).43-45

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) converts glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate. In addition to its role in glycolysis and production of NADH (used for ATP production by OXPHOS), GAPDH also has dual (even opposite) non-metabolic functions. Indeed, on the one hand, it induces cell death,46,47 but on the other hand, GAPDH also induces cyclin B/CDK1 activity48 and accelerates cell cycle progression, possibly by regulating G2/M transition.48,49 Thus, through multifaceted metabolic and metabolism-independent signaling activities, various metabolic enzymes regulate cell cycle progression.

Endothelial cell metabolism

ECs are plastic cell types, which can rapidly switch from protracted periods of quiescence to intense proliferation during angiogenesis.50 Until recently, very little was known about the role and importance of metabolic pathways in ECs during vessel sprouting. Recent studies showed that ECs are glycolysis addicted, producing 85% of their total amount of ATP via this pathway.51 Reliance on anaerobic over aerobic metabolism enables ECs to form new vascular sprouts in avascular areas, devoid of oxygen, which would preclude OXPHOS.52 In a nascent vascular sprout, a navigating migratory tip cell leads the sprout, while trailing proliferating stalk cells elongate the sprout.53 Hyperglycolysis was shown to render ECs more competitive to reach the tip position in the vascular sprout, but glycolysis is also necessary for stalk cell proliferation.51 Targeting the glycolytic activator PFKFB3 reduces glycolysis and suppresses pathological angiogenesis in ischemic and inflamed tissues.54

Unexpectedly, ECs do not rely on fatty acid oxidation for the production of ATP or redox homeostasis, but use fatty acids as a carbon source for the synthesis of DNA during cell replication, unlike multiple other cell types.55 Additional metabolic pathways, including the pentose phosphate pathway, amino acid metabolism and others have been poorly studied in ECs in relation to (pathological) angiogenesis.52,56 A relationship between metabolism and the cell cycle in ECs has not been studied at all.

Endothelial cell plasticity: regulation by Notch

In a newly emerging angiogenic sprout, a migratory tip cell leads trailing proliferating stalk cells that elongate the sprout. 53 After having formed new perfused vessels, ECs become contact-inhibited and resume quiescence again. A critical regulator of angiogenesis is Notch,57 a transmembrane receptor that is proteolytically cleaved into a transcriptionally active Notch intracellular domain (NICD) upon activation by its ligand Dll4.58 During vessel branching, Notch signaling in response to Dll4 controls the specification of EC subtypes into stalk cells,59,60 but it is also a negative regulator of EC proliferation, explaining why inhibition of Dll4-Notch causes EC overgrowth.61,62 The mechanisms via which Notch controls EC proliferation are incompletely understood, but involves binding of NICD with recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa j region (Rbpj) and recruitment of a transcriptional complex to activate transcription of downstream targets including Hairy/enhancer of split (Hes) and Hes-related with YRPW motif protein (Hey) family genes.63 Nuclear NICD levels are controlled by proteasomal degradation, mediated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase F box- and WD repeat domain-containing 7 (FBW7).64 Recent studies revealed that Notch signaling regulates the metabolism of several cell types,65 but how Notch controls glycolysis in ECs during cell cycle progression remained unknown.

Notch: a cell cycle/metabolic brake for G1-to-S transition

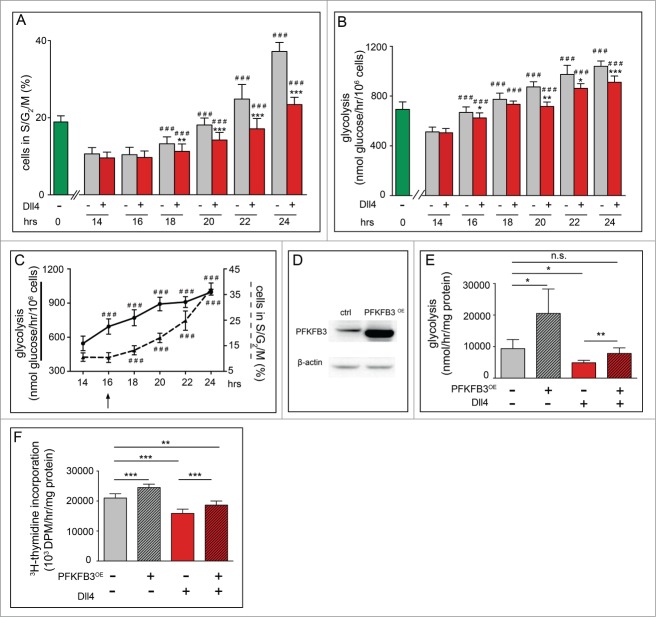

We previously demonstrated that glycolysis produces 85% of all ATP in ECs, and that loss of PFKFB3 reduced EC proliferation.51 We also documented that Notch signaling reduced PFKFB3 levels and glycolytic flux.51 We therefore explored in this study how Notch signaling, glycolysis and the cell cycle were interrelated to each other, using ECs synchronized in G0/G1 by contact inhibition. FACS analysis using Hoechst33342 and PyroninY showed that quiescent ECs entered the S phase around 18 hours after replating (Fig. 3A; gray bars). Interestingly, shortly prior to G1-to-S transition, around 16 hours, glycolytic flux started to rise (Fig. 3B; gray bars). Thus, the time point in the cell cycle, when glycolysis increased and after which cells entered S phase, reflected the nutrient-sensitive restriction point. Plotting the time course of both the glycolytic and cell cycle changes together illustrated that the metabolic changes occurred at the same time or even slightly preceded – but never occurred later than – the time when ECs entered the S-phase (Fig. 3C, arrow). Overall, Notch activation impeded the passage through the nutrient-sensitive restriction point.

Figure 3.

Notch is a metabolic brake for G1 cell cycling in ECs and overexpression of PFKFB3 overcomes the Notch-mediated metabolic brake. For all panels, G0-synchronized ECs (obtained by contact inhibition) were replated and analyzed at the indicated time points. (A) Time course FACS analysis using Hoechst33342 and PyroninY in control (gray) and Dll4-treated ECs (red). Around 18 hours after reseeding, control cells entered S phase. By contrast, fewer Dll4-treated cells entered S phase (average of >10 experiments, each with triplicate measurements; data are mean ± SEM). ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 versus control at the corresponding time point; ### P < 0.001 vs. corresponding baseline (14 hours). Statistics: mixed model statistics considering experiment as co-variant. (B) Time course analysis of glycolytic flux. Around 16 hours after reseeding and beyond, glycolytic flux was increased in control cells but only minimally in Dll4-treated cells (average of 5 experiments, each with triplicate measurements; data are mean ± SEM). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 versus control at the corresponding time point; ### P < 0.001 vs. corresponding baseline (14 hrs); Statistics: mixed model statistics considering experiment as co-variant. (C) Kinetic comparison of metabolic and cell cycle changes after replating of the G0-synchronized cells. Plotting the control data shown in panel A and B together illustrates that the metabolic change (full line) shows an increase preceding (16 hrs, arrow) that of the cell cycle change (dashed line) (average of 5 experiments, each with triplicate measurements; data are mean ± SEM). ### P < 0.001 versus corresponding baseline (14 hrs); Statistics: mixed model statistics considering experiment as co-variant. (D) Representative immunoblot of PFKFB3 for control and PFKFB3OE cells. β-actin is used as loading control. (E) Glycolytic flux, showing enhanced glycolysis upon PFKFB3 overexpression (PFKFB3OE) in control conditions (without Dll4). Dll4 lowers glycolysis, but PFKFB3OE enhances glycolysis again in Dll4-activated cells. (F) [3H]-thymidine incorporation in DNA, showing that PFKFB3OE increases EC proliferation. Dll4 reduces EC proliferation, but PFKFB3OE increases again the proliferation of Dll4-activated ECs. Data in E and F are mean ± SEM of n = 4 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by mixed model statistics considering experiment as co-variant.

Since Notch signaling reduces EC proliferation,66 we explored whether Notch-signaling affected the progression of G1 into S phase in ECs, and therefore replated G0-synchronized ECs and stimulated them with Dll4. FACS analysis of the cell cycle showed that control cells started to enter S phase from 18 hours onwards, while exposure to Dll4 largely attenuated / delayed G1-to-S transition, reducing the number of cells in S/G2/M phase (Fig. 3A). Dll4 also largely attenuated the glycolytic surge at 16 hours and beyond (Fig. 3B).

Overexpression of PFKFB3 overcomes the Notch-mediated metabolic brake

To further explore the functional importance of PFKFB3, we assessed whether overexpression of PFKFB3 (PFKFB3OE) could overcome the block of cell cycle progression by Dll4. We therefore transduced ECs with a lentiviral vector expressing PFKFB3, which increased levels of PFKFB3 protein (Fig. 3D) and the rate of glycolysis (Fig. 3E). The increased levels of glycolysis were accompanied by an increased proliferation rate, as measured by incorporation of 3H-thymidine into DNA (Fig. 3F). Consistent with our previous findings,51 Dll4 lowered glycolysis, but PFKFB3OE increased the reduced glycolysis levels of Dll4-activated ECs to levels found in control cells (Fig. 3E). Dll4 reduced EC proliferation, but PFKFB3OE increased the reduced proliferation rate of Dll4-activated ECs to levels nearly similar as in control cells, thus partially overcoming the suppression of cell cycle progression by Dll4 (Fig. 3F).

Discussion

In this study, we show that Notch signaling in ECs suppresses progression through the cell cycle and concurrently suppresses glycolysis at the nutrient-sensitive restriction point in the cell cycle. Already in the early 70s, Pardee discovered that nutrient availability was required for cells to progress beyond the nutrient-sensitive restriction point.7 However, the molecular regulation of the nutrient-sensitive checkpoint remains incompletely characterized. Our data show that Notch controls cell cycle progression in ECs by regulating the nutrient-sensitive restriction point. Indeed, Dll4 impaired the entry into S phase, and largely abolished the upregulation of glycolysis at the G1-to-S transition. Thus, by preventing glycolysis to rise at the nutrient-sensitive restriction point, Notch signaling provides a “metabolic brake” that impedes passage into S phase. Hence, this signaling pathway participates in fine-tuning the crosstalk between the nutritional status and EC cycling.

Accumulating evidence reveals that alterations in metabolism are not only necessary, but in certain cases also sufficient for cell growth, and that the same signaling pathways that coordinate cell cycle progression control and are controlled by changes in cellular metabolism.67 Given the importance of the nutrient-sensitive checkpoint, it is plausible that metabolism must be tightly coordinated with cell cycle changes and that entry into S phase requires an adapted metabolic rewiring. Indeed, we previously showed that inhibition of PFKFB3 impaired EC sprouting induced by Notch-blockade,51 arguing for a critical role of the metabolic changes induced by Dll4 in the control of EC cycling. Noteworthy in this respect, Notch signaling suppresses transcription of metabolic genes through binding of the repressor hairy,68 suggesting that Notch could regulate rewiring of metabolism, in parallel to its activity on modulating the transcription of cell cycle regulatory molecules.69,70 We now provide additional functional evidence for a causal role of PFKFB3 in driving the EC cycle by demonstrating that overexpression of PFKFB3 (nearly) completely overcame the Notch-induced suppression of proliferation and glycolysis. Together, our findings that Notch-signaling suffices to impair cell cycle progression in ECs suggest an important role of Notch, through regulation of glycolysis, in the temporal control of the cell cycle.

Experimental methods

Chemicals and reagents

Recombinant human Dll4 extracellular domain was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, USA); Endothelial Cell Growth Supplements (ECGS), Heparin, Pyronin Y, and Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), were from Sigma-Aldrich (Bornem, Belgium); Hoechst33342, L-Glutamine and Penicillin/Streptomycin were Life Technologies (Life Technologies, Ghent, Belgium). Radioactively labeled tracers were from Perkin Elmer (Zaventem, Belgium).

Cell culture and treatment: primary cells

Human umbilical vein ECs (HUVEC) were freshly isolated from different donors as previously described71 (with approval of the Medical ethical commission of KU Leuven/University hospital Leuven, and informed consent obtained from all subjects) and used between passage 1 and 5. HUVECs were cultured either in M199 medium (1 mg/ml D-glucose) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Biochrome, Berlin, Germany), 2 mM L-Glutamine, 30 mg/L ECGS, 10 units/mL heparin and Penicillin/ Streptomycin (Life Technologies, Ghent, Belgium), or in endothelial basal medium (EBM-2) supplemented with endothelial growth medium SingleQuots (Clonetics, Lonza, Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium or PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany). Notch pathway modulation: To activate the Notch pathway, cells were grown for 24 hrs on plates coated for 24 hrs at 4°C with recombinant Dll4 extracellular domain at a final concentration of 1 μg/mL as previously described, using BSA coated plates as control.72 ECs were seeded at 150,000/ml/cm2 unless otherwise specified.73 To reach contact inhibition, early passage cells were cultured in M199 medium supplemented with 20% FBS and growth factors for at least 7 days, when approximately 70% of the cell population had reached G0 cell cycle arrest as verified by flow cytometry (see below). Medium was replaced every second day. Lentiviral transductions: For PFKFB3 overexpression, huPFKFB3 was cloned from an ORIGENE plasmid (sc117283) with XhoI and XbaI into pRRLsinPPT CMV/MCSMMWpre viral vector (gift from Max Mazzone, VIB - KU Leuven, Belgium).

Immunoblot analysis

Protein extraction and immunoblot analysis were performed using a modified Laemmli sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 buffer containing 2% SDS and 20% glycerol)74 in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Vilvoorde, Belgium). Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane, and analyzed by immunoblotting. Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-PFKFB3 (60241–1 Proteintech, Manchester, United Kingdom) and rabbit anti-βactin (13E5; No. 4970; Cell Signaling Technology, Bioké, Leiden, the Netherlands). Appropriate secondary antibodies were from Dako (Enschede, the Netherlands). Signal was detected using the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences, GE Healthcare, Diegem, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry

Cell cycle analysis: The G0 and G1 phase of cell cycle was separated by use of Pyronin Y, which preferentially binds to RNA, and Hoechst 33342, which binds to A-T base pairs (DNA). Cells in G0 were identified as a 2N DNA population with their RNA content lower than the level in S phase, as described.3 Briefly, cells were collected by trypsinization, fixed (4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)) and stained for 3 hrs with 20 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 followed by 1 hr staining with 0.1 mg/ml Pyronin Y. Pyronin Y was excited with a 488nm Argon laser and emission was recorded at 575 nm, while Hoechst 33342 was excited with a 405nm Violet Diode laser and emission was recorded at 450 nm. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACS CANTOII (BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium) and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc., Olten, Switzerland).3

Metabolism assays

Glycolysis: Cells were incubated for 2 hrs prior to the experimental time point in growth medium containing 80 mCi/mmol [5–3H]-D-glucose. Thereafter, supernatant was transferred into glass vials sealed with rubber stoppers. 3H2O was captured in hanging wells containing a Whatman paper soaked with H2O over a period of 48 hrs at 37°C to reach saturation. Radioactivity was determined in the paper by liquid scintillation counting.

In vitro assays

Proliferation was quantified by incubating cells for 2 hrs with 1 μCi/mL [3H]-thymidine. Thereafter, cells were fixed with 100% ethanol for 15 min at 4°C, precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and lysed with 0.1 N NaOH. The amount of [3H]-thymidine incorporated into DNA was measured by scintillation counting.

Statistics

Data represent mean ± SEM of representative experiments unless otherwise stated. For in vitro experiments with freshly isolated HUVECs, every experiment was performed at least 3 times using different donors. Statistical significance between groups was calculated by standard t-test (Prism v4.0b) or using mixed model statistics with experiment as random factor to correct for variation between umbilical donors (SAS statistical software version 9.3), as indicated. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

PC declares being named as inventor on patent applications claiming subject matter related to the results described in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the VRC core facilities, and Max Mazzone (VRC, VIB - KU Leuven) for providing pRRLsinPPT CMV/MCSMMWpre viral vector.

Funding

JK, RM, CL are supported by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO); SS is funded by the Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology (IWT). The work of PC is supported by a grant from Belgian Science Policy (IUAP7/03), long-term structural Methusalem funding by the Flemish Government, grants from FWO, the Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network (ARTEMIS), Foundation against Cancer, an European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Research Grant (EU ERC269073) and an AXA Research grant. MD is supported by grants from FWO and Foundation against Cancer.

References

- 1. Buchakjian MR, Kornbluth S. The engine driving the ship: metabolic steering of cell proliferation and death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11:715–27; PMID:20861880; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2011; 27:441–64; PMID:21985671; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lemons JM, Feng XJ, Bennett BD, Legesse-Miller A, Johnson EL, Raitman I, Pollina EA, Rabitz HA, Rabinowitz JD, Coller HA. Quiescent fibroblasts exhibit high metabolic activity. PLoS Biol 2010; 8:e1000514; PMID:21049082; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coller HA. Cell biology. The essence of quiescence. Science 2011; 334:1074–5; PMID:22116874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1216242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Farrell PH. Quiescence: early evolutionary origins and universality do not imply uniformity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2011; 366:3498–507; PMID:22084377; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rstb.2011.0079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foster DA, Yellen P, Xu L, Saqcena M. Regulation of G1 cell cycle progression: Distinguishing the restriction point from a nutrient-sensing cell growth checkpoint(s). Genes Cancer 2010; 1:1124–31; PMID:21779436; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/1947601910392989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pardee AB. A restriction point for control of normal animal cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1974; 71:1286–90; PMID:4524638; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tudzarova S, Colombo SL, Stoeber K, Carcamo S, Williams GH, Moncada S. Two ubiquitin ligases, APC/C-Cdh1 and SKP1-CUL1-F (SCF)-beta-TrCP, sequentially regulate glycolysis during the cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:5278–83; PMID:21402913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1102247108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Almeida A, Bolanos JP, Moncada S. E3 ubiquitin ligase APC/C-Cdh1 accounts for the Warburg effect by linking glycolysis to cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:738–41; PMID:20080744; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0913668107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Colombo SL, Palacios-Callender M, Frakich N, Carcamo S, Kovacs I, Tudzarova S, Moncada S. Molecular basis for the differential use of glucose and glutamine in cell proliferation as revealed by synchronized HeLa cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:21069–74; PMID:22106309; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1117500108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deberardinis RJ, Sayed N, Ditsworth D, Thompson CB. Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2008; 18:54–61; PMID:18387799; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Westermann B. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11:872–84; PMID:21102612; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reinecke F, Smeitink JA, van der Westhuizen FH. OXPHOS gene expression and control in mitochondrial disorders. Biochim Biophy Acta 2009; 1792:1113–21; PMID:19389473; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chatre L, Ricchetti M. Prevalent coordination of mitochondrial DNA transcription and initiation of replication with the cell cycle. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41:3068–78; PMID:23345615; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katajisto P, Döhla J, Chaffer CL, Pentinmikko N, Marjanovic N, Iqbal S, Zoncu R, Chen W, Weinberg RA, Sabatini DM. Stem cells. Asymmetric apportioning of aged mitochondria between daughter cells is required for stemness. Science 2015; 348:340–43; PMID:25837514; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1260384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cornell R, Grove GL, Rothblat GH, Horwitz AF. Lipid requirement for cell cycling. The effect of selective inhibition of lipid synthesis. Exp Cell Res 1977; 109:299–307; PMID:913494; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0014-4827(77)90009-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Atilla-Gokcumen GE, Muro E, Relat-Goberna J, Sasse S, Bedigian A, Coughlin ML, Garcia-Manyes S, Eggert US. Dividing cells regulate their lipid composition and localization. Cell 2014; 156:428–39; PMID:24462247; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh P, Saxena R, Srinivas G, Pande G, Chattopadhyay A. Cholesterol biosynthesis and homeostasis in regulation of the cell cycle. PloS One 2013; 8:e58833; PMID:23554937; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0058833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Welti J, Loges S, Dimmeler S, Carmeliet P. Recent molecular discoveries in angiogenesis and antiangiogenic therapies in cancer. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:3190–200; PMID:23908119; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI70212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bartek J, Bartkova J, Lukas J. The retinoblastoma protein pathway and the restriction point. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1996; 8:805–14; PMID:8939678; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0955-0674(96)80081-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Attwooll C, Lazzerini Denchi E, Helin K. The E2F family: specific functions and overlapping interests. EMBO J 2004; 23:4709–16; PMID:15538380; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Darville MI, Antoine IV, Mertens-Strijthagen JR, Dupriez VJ, Rousseau GG. An E2F-dependent late-serum-response promoter in a gene that controls glycolysis. Oncogene 1995; 11:1509–17; PMID:7478575 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Darville MI, Rousseau GG. E2F-dependent mitogenic stimulation of the splicing of transcripts from an S phase-regulated gene. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:2759–65; PMID:9207022; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/25.14.2759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cam H, Balciunaite E, Blais A, Spektor A, Scarpulla RC, Young R, Kluger Y, Dynlacht BD. A common set of gene regulatory networks links metabolism and growth inhibition. Mol Cell 2004; 16:399–411; PMID:15525513; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goto Y, Hayashi R, Kang D, Yoshida K. Acute loss of transcription factor E2F1 induces mitochondrial biogenesis in HeLa cells. J Cell Physiol 2006; 209:923–34; PMID:16972274; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.20802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blanchet E, Annicotte JS, Lagarrigue S, Aguilar V, Clapé C, Chavey C, Fritz V, Casas F, Apparailly F, Auwerx J, et al. . E2F transcription factor-1 regulates oxidative metabolism. Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13:1146–52; PMID:21841792; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dali-Youcef N, Mataki C, Coste A, Messaddeq N, Giroud S, Blanc S, Koehl C, Champy MF, Chambon P, Fajas L, et al. . Adipose tissue-specific inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein protects against diabesity because of increased energy expenditure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:10703–8; PMID:17556545; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0611568104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hsieh MC, Das D, Sambandam N, Zhang MQ, Nahle Z. Regulation of the PDK4 isozyme by the Rb-E2F1 complex. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:27410–7; PMID:18667418; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M802418200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sakamaki T, Casimiro MC, Ju X, Quong AA, Katiyar S, Liu M, Jiao X, Li A, Zhang X, Lu Y, et al. . Cyclin D1 determines mitochondrial function in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26:5449–69; PMID:16809779; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.02074-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tchakarska G, Roussel M, Troussard X, Sola B. Cyclin D1 inhibits mitochondrial activity in B cells. Cancer Res 2011; 71:1690–9; PMID:21343394; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldin N, Arzoine L, Heyfets A, Israelson A, Zaslavsky Z, Bravman T, Bronner V, Notcovich A, Shoshan-Barmatz V, Flescher E. Methyl jasmonate binds to and detaches mitochondria-bound hexokinase. Oncogene 2008; 27:4636–43; PMID:18408762; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2008.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mathupala SP, Ko YH, Pedersen PL. Hexokinase II: cancer's double-edged sword acting as both facilitator and gatekeeper of malignancy when bound to mitochondria. Oncogene 2006; 25:4777–86; PMID:16892090; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1209603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Tajeddine N, Kroemer G. Disruption of the hexokinase-VDAC complex for tumor therapy. Oncogene 2008; 27:4633–5; PMID:18469866; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2008.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Estevez-Garcia IO, Cordoba-Gonzalez V, Lara-Padilla E, Fuentes-Toledo A, Falfán-Valencia R, Campos-Rodríguez R, Abarca-Rojano E. Glucose and glutamine metabolism control by APC and SCF during the G1-to-S phase transition of the cell cycle. J Physiol Biochem 2014; 70:569–81; PMID:24604252; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s13105-014-0328-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL, Cantley LC. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature 2008; 452:230–3; PMID:18337823; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mazurek S. Pyruvate kinase type M2: a key regulator of the metabolic budget system in tumor cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011; 43:969–80; PMID:20156581; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anastasiou D, Poulogiannis G, Asara JM, Boxer MB, Jiang JK, Shen M, Bellinger G, Sasaki AT, Locasale JW, Auld DS, et al. . Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 by reactive oxygen species contributes to cellular antioxidant responses. Science 2011; 334:1278–83; PMID:22052977; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1211485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lunt SY, Muralidhar V, Hosios AM, Israelsen WJ, Gui DY, Newhouse L, Ogrodzinski M, Hecht V, Xu K, Acevedo PN, et al. . Pyruvate kinase isoform expression alters nucleotide synthesis to impact cell proliferation. Mol Cell 2015; 57:95–107; PMID:25482511; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lv L, Xu YP, Zhao D, Li FL, Wang W, Sasaki N, Jiang Y, Zhou X, Li TT, Guan KL, et al. . Mitogenic and oncogenic stimulation of K433 acetylation promotes PKM2 protein kinase activity and nuclear localization. Mol Cell 2013; 52:340–52; PMID:24120661; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang W, Xia Y, Hawke D, Li X, Liang J, Xing D, Aldape K, Hunter T, Alfred Yung WK, Lu Z. PKM2 phosphorylates histone H3 and promotes gene transcription and tumorigenesis. Cell 2012; 150:685–96; PMID:22901803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang W, Xia Y, Ji H, Zheng Y, Liang J, Huang W, Gao X, Aldape K, Lu Z. Nuclear PKM2 regulates beta-catenin transactivation upon EGFR activation. Nature 2011; 480:118–22; PMID:22056988; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Keller KE, Doctor ZM, Dwyer ZW, Lee YS. SAICAR induces protein kinase activity of PKM2 that is necessary for sustained proliferative signaling of cancer cells. Mol Cell 2014; 53:700–9; PMID:24606918; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yalcin A, Clem BF, Simmons A, Lane A, Nelson K, Clem AL, Brock E, Siow D, Wattenberg B, Telang S, et al. . Nuclear targeting of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB3) increases proliferation via cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem 2009; 284:24223–32; PMID:19473963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M109.016816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Besson A, Gurian-West M, Chen X, Kelly-Spratt KS, Kemp CJ, Roberts JM. A pathway in quiescent cells that controls p27Kip1 stability, subcellular localization, and tumor suppression. Genes Dev 2006; 20:47–64; PMID:16391232; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1384406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yalcin A, Clem BF, Imbert-Fernandez Y, Ozcan SC, Peker S, O'Neal J, Klarer AC, Clem AL, Telang S, Chesney J. 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB3) promotes cell cycle progression and suppresses apoptosis via Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation of p27. Cell Death Dis 2014; 5:e1337; PMID:25032860; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cddis.2014.292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Colell A, Green DR, Ricci JE. Novel roles for GAPDH in cell death and carcinogenesis. Cell Death Differ 2009; 16:1573–81; PMID:19779498; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2009.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sen N, Hara MR, Kornberg MD, Cascio MB, Bae BI, Shahani N, Thomas B, Dawson TM, Dawson VL, Snyder SH, et al. . Nitric oxide-induced nuclear GAPDH activates p300/CBP and mediates apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 2008; 10:866–73; PMID:18552833; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carujo S, Estanyol JM, Ejarque A, Agell N, Bachs O, Pujol MJ. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase is a SET-binding protein and regulates cyclin B-cdk1 activity. Oncogene 2006; 25:4033–42; PMID:16474839; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1209433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sundararaj KP, Wood RE, Ponnusamy S, Salas AM, Szulc Z, Bielawska A, Obeid LM, Hannun YA, Ogretmen B. Rapid shortening of telomere length in response to ceramide involves the inhibition of telomere binding activity of nuclear glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:6152–62; PMID:14630908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M310549200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 2011; 146:873–87; PMID:21925313; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Schoors S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Cantelmo AR, Quaegebeur A, Ghesquière B, Cauwenberghs S, Eelen G, et al. . Role of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell 2013; 154:651–63; PMID:23911327; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Carmeliet P. Role of endothelial cell metabolism in vessel sprouting. Cell Metab 2013; 18:634–47; PMID:23973331; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gerhardt H, Golding M, Fruttiger M, Ruhrberg C, Lundkvist A, Abramsson A, Jeltsch M, Mitchell C, Alitalo K, Shima D, et al. . VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol 2003; 161:1163–77; PMID:12810700; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200302047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schoors S, De Bock K, Cantelmo AR, Georgiadou M, Ghesquière B, Cauwenberghs S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Quaegebeur A, Goveia J, et al. . Partial and transient reduction of glycolysis by PFKFB3 blockade reduces pathological angiogenesis. Cell Metab 2014; 19:37–48; PMID:24332967; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schoors S, Bruning U, Missiaen R, Queiroz KC, Borgers G, Elia I, Zecchin A, Cantelmo AR, Christen S, Goveia J, et al. . Fatty acid carbon is essential for dNTP synthesis in endothelial cells. Nature 2015; 520:192-7; PMID:26245368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ghesquiere B, Wong BW, Kuchnio A, Carmeliet P. Metabolism of stromal and immune cells in health and disease. Nature 2014; 511:167–76; PMID:25008522; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Herbert SP, Stainier DY. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011; 12:551–64; PMID:21860391; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Andersson ER, Sandberg R, Lendahl U. Notch signaling: simplicity in design, versatility in function. Development 2011; 138:3593–612; PMID:21828089; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.063610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lewis J. Notch signalling and the control of cell fate choices in vertebrates. Semin Cell Deve Biol 1998; 9:583–9; PMID:9892564; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/scdb.1998.0266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chitnis AB. The role of Notch in lateral inhibition and cell fate specification. Mol Cell Neurosci 1995; 6:311–21; PMID:8742272; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/mcne.1995.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hellstrom M, Phng LK, Hofmann JJ, Wallgard E, Coultas L, Lindblom P, Alva J, Nilsson AK, Karlsson L, Gaiano N, et al. . Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature 2007; 445:776–80; PMID:17259973; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Siekmann AF, Lawson ND. Notch signalling limits angiogenic cell behaviour in developing zebrafish arteries. Nature 2007; 445:781–4; PMID:17259972; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Roca C, Adams RH. Regulation of vascular morphogenesis by Notch signaling. Genes Dev 2007; 21:2511–24; PMID:17938237; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1589207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Izumi N, Helker C, Ehling M, Behrens A, Herzog W, Adams RH. Fbxw7 controls angiogenesis by regulating endothelial Notch activity. PloS One 2012; 7:e41116; PMID:22848434; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0041116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bi P, Kuang S. Notch signaling as a novel regulator of metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015; 26(5):248–55; PMID:25805408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Segarra M, Williams CK, Sierra Mde L, Bernardo M,McCormick PJ, Maric D, Regino C, Choyke P, Tosato G. Dll4 activation of Notch signaling reduces tumor vascularity and inhibits tumor growth. Blood 2008; 112:1904–11; PMID:18577711; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Locasale JW, Cantley LC. Metabolic flux and the regulation of Mammalian cell growth. Cell Metab 2011; 14:443–51; PMID:21982705; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhou D, Xue J, Lai JC, Schork NJ, White KP, Haddad GG. Mechanisms underlying hypoxia tolerance in Drosophila melanogaster: hairy as a metabolic switch. PLoS Genet 2008; 4:e1000221; PMID:18927626; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Phng LK, Gerhardt H. Angiogenesis: a team effort coordinated by notch. Dev Cell 2009; 16:196–208; PMID:19217422; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Latasa MJ, Cisneros E, Frade JM. Cell cycle control of Notch signaling and the functional regionalization of the neuroepithelium during vertebrate neurogenesis. Int J Dev Biol 2009; 53:895–908; PMID:19598111; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1387/ijdb.082721ml [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest 1973; 52:2745–56; PMID:4355998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI107470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Guarani V, Deflorian G, Franco CA, Krüger M, Phng LK, Bentley K, Toussaint L, Dequiedt F, Mostoslavsky R, Schmidt MH, et al. . Acetylation-dependent regulation of endothelial Notch signalling by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Nature 2011; 473:234–8; PMID:21499261; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature09917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Itahana K, Campisi J, Dimri GP. Methods to detect biomarkers of cellular senescence: the senescence-associated beta-galactosidase assay. Methods Mol Biol 2007; 371:21–31; PMID:17634571; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-59745-361-5_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Carmeliet P, Moons L, Luttun A, Vincenti V, Compernolle V, De Mol M, Wu Y, Bono F, Devy L, Beck H, et al. . Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med 2001; 7:575–83; PMID:11329059; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/87904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]