Abstract

Background

The tort system is supposed to help improve the quality and safety of health care, but whether it actually does so is controversial. Most previous studies modeling the effect of negligence litigation on quality of care are ecologic.

Objective

To assess whether the experience of being sued and incurring litigation costs affects the quality of care subsequently delivered in nursing homes.

Research Design, Subjects, Measures

We linked information on 6,471 negligence claims brought against 1,514 nursing homes between 1998 and 2010 to indicators of nursing home quality drawn from two U.S. national datasets (Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting system; Minimum Data Set Quality Measure/Indicator Reports). At the facility level, we tested for associations between 9 quality measures and 3 variables indicating the nursing homes’ litigation experience in the preceding 12–18 months (total indemnity payments; total indemnity payments plus administrative costs; ≥1 paid claims vs. none). The analyses adjusted for quality at baseline, case-mix, ownership, occupancy, year, and facility and state random effects.

Results

Nearly all combinations of the 3 litigation exposure measures and 9 quality measures—27 models in all—showed an inverse relationship between litigation costs and quality. However only a few of these associations were statistically significant, and the effect sizes were very small. For example, a doubling of indemnity payments was associated with a 1.1% increase in the number of deficiencies and a 2.2% increase in pressure ulcer rates.

Conclusions

Tort litigation does not increase the quality performance of nursing homes, and may decrease it slightly.

Keywords: malpractice, nursing homes, quality of care

Introduction

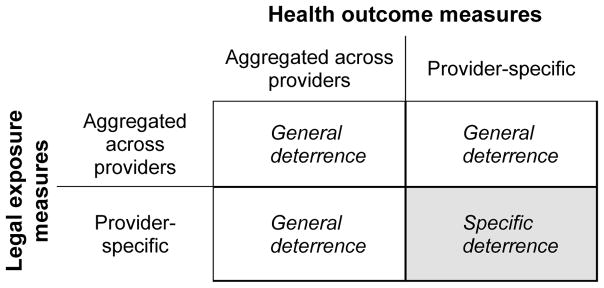

Deterrence is a key objective of the tort system.(1) According to classic deterrence theory, by imposing economic penalties and reputational costs on health care providers who cause negligent harm, litigation creates incentives to be more careful, thereby improving the quality of care.(2) Deterrence theorists have described two distinct mechanisms of action.(3, 4) “General deterrence” refers to the threat of being sued or punished prevailing in society at large: potential wrongdoers watch their step because they recognize they may be visited by legal sanctions if they do not. “Specific deterrence” arises from direct personal experience: wrongdoers who are sanctioned become less likely to reoffend.

How well medical malpractice, one branch of the tort system, deters substandard care has long been a subject of intense debate.(5) The plaintiff’s bar argues that it operates as an important check on unsafe care. Physicians and liability insurers agree that malpractice litigation influences care delivery but argue the influence manifests as “defensive medicine”, negatively impacting quality of care. This debate endures partly because extant research on malpractice litigation’s deterrent value has substantial weaknesses.(5)

The standard approach taken by studies of deterrence in the medical liability system involves correlating providers’ litigation exposure—as measured by the volume of malpractice claims or payments, the costs of liability insurance, or the mix of in-force tort reforms in the practice environment—with patient outcomes. In general, these studies(6–10) have detected little or no effect of litigation on quality.

A notable weakness of these studies is their ecologic nature: they aggregate measures of litigation exposure, health outcomes, or both at the state or regional level.(11) Ecologic analyses can only provide estimates of general deterrence. Testing for specific deterrence requires linking longitudinal data on litigation experiences and health outcomes at the provider level (Figure 1). This is logistically difficult across large numbers of providers, as large-scale, longitudinal data repositories with both quality and claims data are rare.

Figure 1.

Detectable forms of deterrence in studies of medical malpractice litigation, by type of measures used

These data obstacles explain the predominant research focus on general deterrence and may, in turn, explain why no robust connection between litigation and quality has been detected. For the experience of being sued or paying damages to visit a small minority of providers and then lift the average performance of the wider group to which those providers belong, it would have to be a potent force indeed. By contrast, the relationship between a provider’s experience with litigation’s tribulations and costs and their own performance is likely to be stronger. That is, if deterrence works, specific deterrence is likely to be its most sensitive expression.

In contrast to acute care, several features of the nursing home sector facilitate investigations of specific deterrence. Regarding quality, process and outcome measures are routinely collected for nearly all nursing homes in the U.S. and are widely used in research. Regarding litigation, claims typically target individual facilities as defendants. Consequently, nursing home quality measurement and claims activity both converge at the level of the facility. In addition, the dominance of large nursing home chains provides natural aggregation points for data on facilities’ claims experience.

We analyzed the relationship between the litigation experience and quality performance of nearly 1500 facilities across 48 states. Specifically, we assessed the effect of being sued and making payments on health outcomes and compliance with regulatory standards. If specific deterrence operates as tort theory suggests, quality should improve in the wake of lawsuits. However, litigation could have the opposite effect, undercutting performance, as resources that otherwise would have been directed to maintaining and improving quality are absorbed defending and paying claims.

Methods

Data

We obtained data on all tort claims brought against facilities owned by five of the largest U.S. nursing home chains. The claims closed between 1998 and 2010. We defined a claim as a written demand for compensation for injury arising from care. Data included all claims, regardless of whether they resulted in indemnity payments or were resolved in- or out-of-court. The information on each claim included the type of injury alleged; dates of the incident, claim filing, and claim closure; the amount of indemnity (if any) paid to the plaintiff; and the administrative costs incurred defending the claim.

Nursing home data came from two sources: the Minimum Data Set (MDS) facility-level quality indicator/quality measure system and the On-line Survey, Certification, and Reporting (OSCAR) system. MDS measures are designed to track residents’ functional, cognitive, and affective levels, and facilities have been required to collect these data at least quarterly since June 1998. Facility-level MDS measures have demonstrated good reliability and validity in measuring nursing home quality.(12–14)

From the MDS variables, we selected five measures of interest: pressure ulcers among “high risk” residents; pressure ulcers among “low risk” residents; use of physical restraints; late loss ADL decline; and urinary tract infections (see Appendix 1 for details on all quality measures). Values for these variables indicate the prevalence of the condition in a facility’s residents; hence, higher values suggest lower quality. Groups of these measures have been used in previous studies of nursing home quality and, together, provide a reasonable moment-in-time snapshot of quality of care.(15–17)

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Systems collects and maintains OSCAR data, consisting of survey and certification data for all Medicaid- and Medicare-certified nursing homes in the U.S.(18) State regulators must inspect facilities at least once every 15 months, and the average time between inspections is approximately one year. Facilities also submit facility, resident, and staffing information. When a facility is found to be out of compliance with federal regulatory standards, a deficiency is recorded, noting its type, scope, and severity.

From the OSCAR variables, we selected four measures of interest: number of deficiencies identified on inspection; number of serious deficiencies (violations involving actual harm or immediate jeopardy to residents);(19) and registered nurse and nurse aide staffing (both specified as hours-per-resident-day). To eliminate erroneous values, we followed previously used methods.(20, 21) OSCAR data are widely used as quality measures in research.(15–17) Although limitations have been identified,(22) OSCAR data are the most comprehensive source of facility-level information on nursing homes’ operations, resident characteristics, and regulatory compliance.

In addition to the claims and quality variables, we extracted from OSCAR and added to both datasets other facility characteristics, including resident census, resident acuity, and payer-mix. Analyses of the relationships of interest adjusted for these variables.

Using these longitudinal data, we constructed two analytic datasets. One dataset consisted of the litigation claims data merged with MDS data at the facility calendar-quarter level (“facility-quarter”). The second dataset consisted of litigation claims data merged with OSCAR data at the facility-OSCAR inspection period level (“facility-inspection period”). In merging the litigation claims data with the nursing home data, claims were assigned to the MDS facility-quarter or OSCAR inspection period in which the claim was closed. (When a claim results in an indemnity payment to the plaintiff, the closure date is normally the date at which payment is made.)

Analysis

We used random-effects multivariable regression analysis to estimate the relationship between each facility’s litigation experience during an “exposure period” and the quality of care immediately following the exposure period. The outcome variables were, respectively, the five MDS quality measures and the four OSCAR quality measures described above. Each outcome of interest was modeled separately. Significance levels were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. The predictor of interest was each facility’s litigation experience over time. We tested three different specifications of litigation experience: (i) the sum of indemnity payments made in the exposure period (linear variable in 2010 dollars, log transformed); (ii) the sum of indemnity payments plus administrative costs in the exposure period (linear variable in 2010 dollars, log transformed); and (iii) whether one or more indemnity payments were made in the exposure period (binary variable).

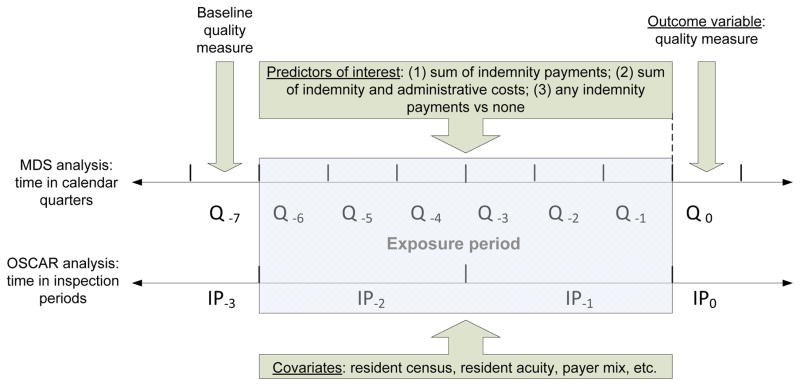

Figure 2 depicts our analytic approach. The shaded area represents the exposure period. In analyses involving the MDS measures, the exposure period consisted of six consecutive quarters (18 months); the predictors of interest—the three litigation variables described above—were calculated over this exposure period and tested against each MDS quality measure in successive regression models. The analyses involving the OSCAR measures adopted the same approach, except the exposure period was 2 consecutive inspection periods—intervals ranging from 18 to 30 months, depending on when surveyor inspections occurred.

Figure 2.

Timeline for the measures of quality-of-care and litigation experience used in the analyses of nursing homes*

* The Figure shows temporal aspects of the variables used to estimate the effect of a nursing home’s claims experience during an “exposure” period on subsequent quality of care. MDS refers to the Minimum Data Set quality indicator/quality measure system. OSCAR refers to the to the Online Survey Certification and Reporting system. Q refers to quarters, the time interval used to construct the analytic dataset containing MDS measures. IP refers to inspection periods, the time interval used to construct the analytic dataset containing OSCAR measures.

Choosing the duration of the exposure period was a balancing exercise. On the one hand we sought to allow sufficient time for a facility’s litigation experience to exert an effect (positive or negative) on its care quality. On the other hand, we sought to minimize the potential for facility quality to be influenced by factors other than litigation.

All models controlled for quality at baseline, which was specified as the value of the quality measure under analysis immediately prior to the exposure period (Figure 1). Other covariates in the models were: the facilities’ resident census, acuity, and payer-mix (averaged over each exposure period); dummy-coded variables indicating the chain to which each facility belonged; dummy-coded variables for each year to capture linear time-trends; and facility and state random-effects. Standard errors were adjusted for autocorrelation among the residuals.

We log transformed the MDS quality measures to stabilize the variance of the residuals; for consistency in presentation, we did the same for the OSCAR measures. Because the outcome variables and the two continuous predictors are on the log scale, the coefficients in our models indicate the percentage change in quality associated with a percentage change in litigation costs. For simplicity, we present the effects on quality of doubling the litigation cost variables.

Results

Characteristics of negligence claims

Plaintiffs filed 6,471 claims against the 1,514 nursing homes in our sample during the study period. On average, facilities experienced a claim every two years (annual mean, 0.53; std dev, 0.57), although there was substantial variation across homes in their litigation experience. A total of 5,226 (81%) of these claims had closed by the date of data extraction. All results reported hereafter relate only to the closed claims.

Expenditures on the closed claims totaled $968 million, consisting of $785 million in indemnity payments and $182 million in administrative costs. Two-thirds of plaintiffs received payments, at an average of $226,647 per paid claim (Table 1). The most prevalent types of harm alleged in the claims were falls (25.6% of claims), pressure ulcers (13.2%), and dehydration, malnutrition or weight loss (6.7%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of negligence claims against nursing homes

| Claims per nursing home per year, mean (std dev.) | 0.30 | (0.46) |

| Claims paid, % | 66 | -- |

| Compensation per paid claim, $ (std dev.) * | 226,647 | (450,609) |

| Most prevalent negligent harms alleged, n (%) † | ||

| Falls | 1337 | (25.6) |

| Pressure ulcers, bed sores | 692 | (13.2) |

| Dehydration, malnutrition, weight loss | 348 | (6.7) |

| Physical or verbal abuse | 229 | (4.4) |

| Death from unknown causes | 196 | (3.8) |

| Medication errors | 183 | (3.5) |

Monetary values in 2010 dollars.

Some claims involved multiple allegations (6,060 allegations in 5,226 claims).

Characteristics of nursing homes

On average, the nursing homes had approximately 0.5 registered nurse hours-per-resident-day and 2.1 nurse aide hours-per-resident-day (Table 2). OSCAR surveys identified an average of 7.0 deficiencies and 0.5 serious deficiencies per facility inspection. Mean quarterly rates for the five MDS measures ranged from 3.3% of low-risk residents with pressure ulcers to 18.0% of residents with late-loss ADL decline.

Table 2.

Characteristics of nursing homes *

| Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| MDS quality indicator - % of residents | ||

| Decline in late-loss Activities of Daily Living | 18.0 | 8.2 |

| Pressure ulcers among high-risk residents | 15.4 | 8.3 |

| Urinary tract infections | 9.4 | 5.3 |

| Use of restraints | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| Pressure ulcers among low-risk residents | 3.3 | 4.6 |

| Deficiencies – no. | ||

| Deficiencies | 7.0 | 5.8 |

| Serious deficiencies † | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| Staffing – hours per resident day | ||

| Registered and licensed practical nurses | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Nurse aides | 2.1 | 1.2 |

| Residents – no. | 99.0 | 43.5 |

| Casemix | ||

| Medicare as primary payer - % of residents | 16.1 | 13.1 |

| Medicaid as primary payer - % of residents | 59.6 | 19.9 |

| Limitations to Activities of Daily Living score - mean | 3.9 | 0.5 |

| Acuity Index - mean ‡ | 10.2 | 1.4 |

Data consisted of 1514 nursing homes, 68,81 quarters, and 16,158 inspection periods. Values for deficiencies, casemix variables, and staffing and resident number variables are calculated the facility-inspection period level. Values for MDS quality indicators are calculated at the facility-quarter level.

Defined as deficiencies rated G (actual physical or emotional harm) or higher.

An index based on the proportion of residents with various limitations to Activities of Daily Living and the proportion receiving respiratory care, suctioning, IV therapy, tracheostomy care, and parenteral feeding (range of 0–38).

Impact of claims payments on quality

Twenty-three of the 27 relationships examined showed a negative association between exposure to litigation and subsequent performance on quality (Table 3). In other words, higher litigation costs were associated with lower subsequent quality. However, only four of these associations were statistically significant and the effect sizes were small.

Table 3.

Effects of litigation experience over preceding period on quality of nursing home care *

| Quality measures | % change in quality measure with doubling of indemnity paid | % change in quality measure with doubling of indemnity paid plus administrative costs | % change in quality measure moving from no paid to ≥1 paid claims † | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | (95% CI) | P | Change | (95% CI) | P | Change | (95% CI) | P | |

| Pressure ulcers (high) | 0.38 | (−0.37 to 1.13) | 0.32 | 0.48 | (−0.18 to 1.14) | 0.16 | 3.10 | (0.12 to 6.16) | 0.04 |

| Pressure ulcers (low) | 2.26 | (−0.01 to 4.57) | 0.05 | 2.19 | (0.21 to 4.26) | 0.03 | 3.30 | (−5.40 to 12.80) | 0.47 |

| Use of restraints | −1.17 | (−2.41 to 0.09) | 0.07 | −0.71 | (−1.80 to 0.39) | 0.21 | 1.81 | (−3.05 to 6.91) | 0.47 |

| Late loss ADL decline | −0.27 | (−0.76 to 0.23) | 0.30 | −0.21 | (−0.65 to 0.23) | 0.35 | 0.39 | (−1.55 to 2.36) | 0.70 |

| Urinary tract infections | 0.22 | (−0.47 to 0.92) | 0.53 | 0.24 | (−0.36 to 0.86) | 0.43 | 1.09 | (−1.62 to 3.87) | 0.43 |

| All deficiencies | 1.13 | (0.32 to 1.95) | 0.006 | 0.84 | (0.12 to 1.57) | 0.02 | 0.77 | (−2.51 to 4.17) | 0.65 |

| Serious deficiencies | 0.42 | (−0.05 to 0.88) | 0.08 | 0.27 | (−0.15 to 0.68) | 0.21 | 1.25 | (−0.67 to 3.20) | 0.20 |

| RNs (hrs per resident day) | −0.10 | (−0.26 to 0.06) | 0.24 | −0.09 | (−0.23 to 0.06) | 0.24 | −0.46 | (−1.11 to 0.19) | 0.16 |

| Nurse aids (hrs per resident day) | −0.04 | (−0.33 to 0.25) | 0.79 | −0.01 | (−0.27 to 0.25) | 0.95 | −0.43 | (1.60 to 0.76) | 0.48 |

All regressions adjust for baseline quality, payer mix, case mix, chain, year, state, and the number of residents at the facility.

Positive valued indicates higher (geometric) mean score for paid claims.

In the OSCAR analyses, a doubling of indemnity payments made over the preceding two inspection periods was associated with a 1.1% increase in the number of deficiencies, and doubling of total indemnity plus administrative costs was associated with a 0.8% increase in deficiencies. In the MDS analyses, a doubling of total indemnity and administrative costs made over the preceding 18 months period was associated with a 2.2% increase in pressure ulcer rates. Finally, facilities that made one or more indemnity payments had a 3.1% higher rate of pressure ulcers among high-risk residents than facilities that made no indemnity payments. Detection of these four significant associations in 27 separate tests of association may have been due to chance alone. None of the other 23 combinations of litigation and quality variables were significant at the P<0.05 level, although several were close.

Sensitivity analyses

To test whether our findings were sensitive to our specifications of litigation experience, we allowed the predictors to take non-zero values only if their accumulated dollar value over the exposure period exceeded $10,000. The coefficients changed in these analyses, but the overall story was very similar: only three-of-27 associations were statistically significant and all effects were small.

We also ran subanalyses examining the relationship between specific outcome measures and claims in which the injury complained of was that same outcome. This was possible for two outcomes (falls and pressure ulcers). Neither of these targeted subanalyses showed a statistically significant relationship between payment and subsequent quality.

Discussion

This longitudinal study of more than 1,500 nursing homes found little relationship between payments of damages by facilities in negligence litigation and the subsequent quality of care they delivered. Across a range of different measures of litigation experience and facility quality, only a few significant relationships were detected, and they were small inverse associations between levels of payment and levels of subsequent performance. In sum, our findings suggest that tort litigation has no substantial association—positive or negative—with quality of care in the nursing home sector.

Only a few studies have linked litigation experiences with quality performance at the provider level, and they have substantial limitations. In a sample of obstetricians practicing in Florida between 1977 and 1983, Sloan and colleagues found no significant associations between claim frequency and any of five birth outcomes.(23) A weakness of this study was its cross-sectional design, which limited its ability to control for confounding and infer causal relationships. Another study consisted of a series of investigations conducted during and after the Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS).(24) Based on the review of over 30,000 randomly-selected patient records and malpractice claims files in New York State in 1984, researchers investigated the association between hospitals’ past claims experience and their current costs per admission and adverse event rates. The original attempts by HMPS investigators to find a relationship were inconclusive.(5, 10) A later, more sophisticated re-analysis of the data found a negative association between the number of claims against hospitals and their subsequent adverse event rates, but none of the other outcome-exposure combinations tested showed significant relationships.(5) One weakness of the HMPS deterrence analyses was that the main quality measure used, hospital adverse event rates, was cross-sectional, because it was obtained during a single medical record review. More problematic was the misalignment between the litigation and quality measures: the HMPS analyses linked litigation brought against physicians working in the hospitals to hospital-level quality indicators.(10) A third study by Troyer and colleagues assessed the impact of claims against nursing homes on inspection-related quality measures, finding a modestly negative impact of claims on quality.(25) However, these analyses were largely exploratory in nature, included only 48 malpractice claims, and focused on a single state (Florida) for the time period 1993–1997.

By using longitudinal information on quality performance and litigation experience and ensuring the locus of both measures was the same, our study avoids the design problems of earlier investigations of specific deterrence. We provide strong evidence that the tort system is failing to fulfill its deterrence function, at least within the nursing home sector. Indeed, our findings suggest that if negligence litigation is having any effect on quality, it is a mildly damaging one.

Why does negligence litigation fall short on its promise to improve quality and safety? There are several possible explanations. First, the tort system’s quality improvement signal may be thwarted by poor targeting. Previous studies suggest that negligence litigation lacks precision, chiefly in finding and penalizing instances of medical injury and substandard care,(26, 27) and to a lesser extent in assigning indemnity payments to worthy plaintiffs once claims are made.(28) In an earlier analysis of the same sample of nursing homes, we found that high-quality facilities were only marginally less likely to be sued for negligence than their lower-performing counterparts and hypothesized then that such weak discrimination may subvert litigation’s capacity to affect quality.(11) Findings from the current study provide empirical support for that hypothesis.

Second, tort scholars have suggested that cost externalization blunts deterrence by partially insulating wrongdoers from litigation’s economic costs.(5, 29, 30) This potential blocking is particularly salient in the context of medical malpractice, where most physicians carry deep, first-dollar liability coverage with million dollar limits, and premiums are generally community-rated within specialties. Among the facilities we studied, the insurance buffer operated in a different way. The facilities were parts of chains which tended to self-insure for liability risk up to a threshold dollar amount and purchase insurance to cover losses above that threshold. For individual facilities, the chain’s self-insurance fund and the external liability insurance covered their litigation costs. However, some costs of defending and paying claims were passed down to individual facilities through accounting mechanisms tying elements of their budgets to claims experience. This is consistent with a general trend among nursing home chains toward corporate shielding practices that involve locating greater legal and fiscal responsibility at the facility level.(31)

Third, the lags between incident occurrence, claim filing, and claim closure may further attenuate the potential for the experience of making a payment to influence care practices. The median time between the incident and filing dates in our sample was 157 days, and it was 511 days between filing and case closure. Although these average intervals are considerably shorter than equivalents in acute care litigation,(28) they imply individuals involved in particular allegations (e.g., administrators and direct-care staff) may no longer be facility employees when sanctions arrive,(32) potentially undercutting institutional learning opportunities.

Fourth, nursing homes are highly regulated,(33) with heavy government involvement in quality assurance. This form of oversight is regular and predictable. If facilities’ quality improvement efforts are oriented toward fulfilling regulatory requirements, it may contract litigation’s sphere of influence. From the facilities’ perspective, tort litigation could look relatively irregular and unpredictable, and the returns from organizing to try to avert it may be less certain.

Finally, some tort scholars may reject the premise that negligence litigation ought to be held accountable for improving quality and safety. Technically, negligence law’s focus is care that falls below acceptable professional standards;(1) it has no mandate to sanction care that is “merely” suboptimal or below average. Thus, the measures of quality we examined may be the wrong ones. To illustrate by extreme scenario, if all the facilities we observed consistently delivered non-negligent care, the absence of a boost in quality following litigation would say nothing about how well tort law was performing its deterrence function.

Although technically correct, this objection is unsatisfactory. Unsafe care processes are likely to elevate risks of adverse events across the board, from the kind of quality decrements we examined to negligent errors.(34) More important, as we have argued elsewhere,(11) stripping the deterrence function down to the discouragement of isolated episodes of negligent care, and delinking it from aspirations to lift institutional performance more broadly, sets its sights very low indeed. Such a meager conception of deterrence is out of step with the foundational status and attention deterrence is accorded in tort law.

Our study design has limitations that are important to note. First, the experience of nursing homes from the five chains studied may not generalize to other facilities or health care sectors. In particular, it is unclear how generalizable our findings are to tort litigation in the acute care sector, where individual clinicians are the chief targets of claims and different allegation types prevail (e.g. missed diagnoses and technical errors).(35) Second, although our results were robust to targeted analyses matching quality measures to the allegations that led to payouts (e.g., pressure ulcers), the measures we use to characterize quality may not have captured fully facilities’ responses to litigation payments; indeed, some aspects of facilities’ quality response may be unmeasured.(36) Third, to the extent that the facilities’ parent companies shouldered the financial burden of claims, we may have overestimated the facilities true exposure to the duress of litigation.

Tort litigation against health care providers is supposed to improve the quality and safety of health care. This study of nursing home care, designed to detect the subtlest form of deterrence, found none. It joins a mounting body of evidence that tort litigation does not improve health care quality. Virtually all the tort reforms debated over the last four decades in the U.S., including those targeting nursing homes (35), have been designed to reduce litigation’s scale and cost. A common objection to more sweeping reforms, such as non-negligence based administrative approaches to compensation, is that they would pose an unacceptable threat to tort litigation’s quality assurance role.(37, 38) It may be time to accept that this rationale for the current system is misguided, and refocus attention on reforms that would enhance the system’s capacity to achieve its other chief function—compensation.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1. Description of Outcome and Control Variables Used in Analyses

Acknowledgments

Funding: The authors acknowledge funding from the Harvard Interfaculty Program for Health Systems Improvement. Dr. Studdert was supported by a Laureate Fellowship from the Australian Research Council.

References

- 1.Keeton W, Dobbs D, Keeton R, et al. Prosser and Keeton on torts. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danzon P. Liability for Medical Malpractice. In: Culver A, Newhouse J, editors. Handbook of Health Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier North Holland; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shavell S. Foundations of economic analysis of law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahan D. The secret ambition of deterrence. Harv Law Rev. 1999;113:413–500. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mello MM, Brennan TA. Deterrence of medical errors: theory and evidence for malpractice reform. Tex Law Rev. 2002;80:1595–1637. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler D, McClellan M. Do Doctors Practice Defensive Medicine? Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1996;111:353. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubay L, Kaestner R, Waidmann T. The impact of malpractice fears on cesarean section rates. J Health Econ. 1999;18:491–522. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(99)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhankhar P, Khan MM. Threat of Malpractice Lawsuit, Physician Behavior and Health Outcomes: Testing the Presence of Defensive Medicine. 2005 Unpublished manuscript available at: http://wwwaeaweborg/assa/2005/0107_0800_1213pdf.

- 9.Currie J, MacLeod BM. First Do No Harm? Tort Reform and Birth Outcomes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2008;123:795–830. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y, Studdert DM. Does Tort Law Improve the Health of Newborns, or Miscarry? A Longitudinal Analysis of the Effect of Liability Pressure on Birth Outcomes. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. 2012;9:217–245. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Studdert DM, Spittal MJ, Mello MM, et al. Relationship between quality of care and negligence litigation in nursing homes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1243–1250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1009336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mor V, Berg K, Angelelli J, et al. The quality of quality measurement in U.S. nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2003;43(Spec No 2):37–46. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karon SL, Sainfort F, Zimmerman DR. Stability of nursing home quality indicators over time. Med Care. 1999;37:570–579. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199906000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman DR, Karon SL, Arling G, et al. Development and testing of nursing home quality indicators. Health Care Financ Rev. 1995;16:107–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC. Private equity investment and nursing home care: is it a big deal? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:1399–1408. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevenson DG. Nursing home consumer complaints and their potential role in assessing quality of care. Med Care. 2005;43:102–111. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabowski DC, Stevenson DG. Ownership conversions and nursing home performance. Health services research. 2008;43:1184–1203. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Accessed June 26, 2012]; For more information on the OSCAR database, see http://healthindicators.gov/Resources/DataSources/OSCAR_202/Profile. Available.

- 19.Wiener JM, Stevenson DG. State policy on long-term care for the elderly. Health affairs (Project Hope) 1998;17:81–100. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.3.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kash BA, Hawes C, Phillips CD. Comparing staffing levels in the Online Survey Certification and Reporting (OSCAR) system with the Medicaid Cost Report data: are differences systematic? Gerontologist. 2007;47:480–489. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Grabowski DC. Nursing home staffing and quality under the nursing home reform act. Gerontologist. 2004;44:13–23. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Government Accountability Office. Federal Monitoring Surveys Demonstrate Continued Understatement of Serious Care Problems and CMS Oversight Weaknesses (US GAO-08–517) Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sloan FA, Whetten-Goldstein K, Githens PB, et al. Effects of the threat of medical malpractice litigation and other factors on birth outcomes. Med Care. 1995;33:700–714. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability- adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72:429–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troyer JL, Thompson HG., Jr The impact of litigation on nursing home quality. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2004;29:11–42. doi: 10.1215/03616878-29-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:245–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107253250405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Studdert DM, Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, et al. Negligent care and malpractice claiming behavior in Utah and Colorado. Medical care. 2000;38:250–260. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024–2033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz G. Reality in the economic analysis of tort law: does tort law really deter? UCLA Law Rev. 1994;42:377–444. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mello M, Studdert D, Thomas E, et al. Who Pays for Medical Errors? An Analysis of Adverse Event Costs, the Medical Liability System, and Incentives for Patient Safety Improvement. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. 2007;4:835–860. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevenson DG, Bramson JS, Grabowski DC. Nursing Home Ownership Trends and Their Impacts on Quality of Care: A Study Using Detailed Ownership Data from Texas. Journal of Aging and Social Policy. 2012 doi: 10.1080/08959420.2012.705702. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donoghue C. Nursing home staff turnover and retention: an analysis of national level data. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2010;29:89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walshe K. Regulating U.S. nursing homes: are we learning from experience? Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:128–144. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Studdert DM, Stevenson DG. Nursing home litigation and tort reform: a case for exceptionalism. Gerontologist. 2004;44:588–595. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.5.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weisbrod BA. The Nonprofit Economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia AB, et al. “Health courts” and accountability for patient safety. Milbank Q. 2006;84:459–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Studdert DM, Brennan TA. No-fault compensation for medical injuries: the prospect for error prevention. JAMA. 2001;286:217–223. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Description of Outcome and Control Variables Used in Analyses