Abstract

BACKGROUND

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing PEG vs. NaP are inconsistent.

OBJECTIVE

Compare the efficacy of and tolerance to PEG vs. NaP for bowel preparation.

METHODS

We used MEDLINE and EMBASE to identify English-language RCTs published between 1990 and 2008 comparing 4 L PEG with two 45 ml doses of NaP in adults undergoing elective colonoscopy. We calculated the pooled odds ratios (ORs) for preparation quality and proportion of subjects completing the preparation.

RESULTS

From 18 trials (n=2792), subjects receiving NaP were more likely to have an excellent or good quality preparation than those receiving PEG (82% vs. 77%; OR=1.43; 95% CI, 1.01-2.00). Among a subgroup of 10 trials in which prep quality was reported in greater detail, there were no differences in the proportions of excellent, good, fair or poor preparation quality. Among nine trials that assessed preparation completion rates, patients receiving NaP were more likely to complete the preparation than patients receiving 4-L PEG (3.9% vs. 9.8%, respectively, did not complete the preparation; OR= 0.40; CI, 0.17-0.88).

CONCLUSION

Among 18 head-to-head RCTs of NaP vs. 4 L PEG, NaP was more likely to be completed and to result in an excellent or good quality preparation.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Bowel preparation, Polyethylene Glycol, Sodium Phosphate

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that 14 million colonoscopies were performed in the United States in 2002 1. Adequate preparation of the bowel is necessary for optimal visualization of the colonic mucosa 2. Patients often state that preparation (prep) for colonoscopy (CY) is the worst part of entire process. 3, 4 The difficulty with preparation may be related to taste and/or volume of the prep, resulting side effects, or use of adjunctive medications.

Of the commercially available preps, PEG and NaP are most commonly used. Introduced in 1980, polyethylene glycol (PEG) (NuLYTELY, and GoLYTELY; Braintree Laboratories, Inc, Braintree, MA; Colyte; Schwarz Pharma, Milwaukee, WI,) is an orally administered isotonic solution 5. Since PEG is nondigestible and nonabsorbable, it cleanses the colon by washout of intraluminal contents 6. Because it is iso-osmolar with plasma, the large volume of PEG does not result in significant fluid shifts. It has been shown to be highly effective when taken as instructed (4L of PEG solution) 7, 8. However, the efficacy of standard 4 L PEG outside of clinical trials is compromised by poor patient compliance. The large volume and taste are the main factors that contribute to poor patient compliance and tolerability 9, 10, which led to development of reduced PEG volume solutions with or without laxatives, a sulfate-free version, and flavored PEG solutions (HalfLytely or 2-L PEG, NuLYTELY, TriLite) in an attempt to reduce the sulfate odor and improve taste 11, 12. Despite these improvements, nausea and abdominal discomfort commonly result in poor prep quality, the need for repeat procedures and higher costs13.

Sodium phosphate (NaP) solution, a buffered saline laxative, gained popularity as an alternative method for colonic preparation largely due to its smaller volume. Containing monobasic sodium phosphate and dibasic sodium phosphate, NaP acts as an osmotic laxative, cleansing the colon by drawing fluids into the gastrointestinal tract. In addition, NaP tablets (Visicol ®) were designed to improve the taste and reduce the volume required for bowel preparation. Several randomized trials comparing PEG and NaP suggest that NaP is safe, cost effective, better tolerated, and equally or more effective than PEG 6, 14-17.

Previous meta-analyses comparing these two preps are either not current 6, include pediatric trials and off-label doses of NaP 18, or include atypical doses of both preps 19. The objective of this study was to use meta-analysis to compare the efficacy of and adherence to 4L PEG vs. two 45 ml doses of NaP preps for elective colonoscopy in adults.

METHODS

Search Strategy and selection criteria

We searched the medical literature from 1990 to 2008 using MEDLINE and EMBASE bibliographic databases to identify all relevant English language publications. The search strategy used the following MeSH search terms: 1) colonoscopy, 2) polyethylene glycol, 3) phosphates, 4) cathartics and 5) bowel prep. We limited these sets of articles to diagnostics and therapeutic uses and to human studies published in English that compared 4 L PEG vs. two 45 mL doses of NaP in adults undergoing elective colonoscopy. In addition, we hand-searched the reference lists of every primary study for additional publications. The following criteria were used to select studies for inclusion: 1) study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 2) patient population: adult patients undergoing elective colonoscopy, 3) dosing and frequency schedules of PEG and NaP. We excluded trials that were duplicate studies and those that lacked categorical data on both prep quality and adherence. We also excluded review articles, editorials, letters to editor, and studies published only in abstract form. Decisions about study inclusion and exclusion were made independently by two authors (R.J., T.F.I), with disagreements resolved by discussion.

Quantitative analysis

Descriptive data were abstracted to determine clinical similarity of the trials. We abstracted quantitative data for each trial, including the number of subjects in each treatment group and those with each outcome. Data extraction was performed primarily by one author, with random checks by a second author. Discrepancies in the data extraction process were resolved by discussion. Forrest plots were used to summarize the treatment effect for each trial. In combining data from the trials, we assumed the presence of heterogeneity prior to pooling the data and accordingly used the random effects model developed by DerSimonian-Laird20 , which allows adjustment for variability among trials by providing a more conservative estimate of the range of an effect through wider confidence intervals (CIs).

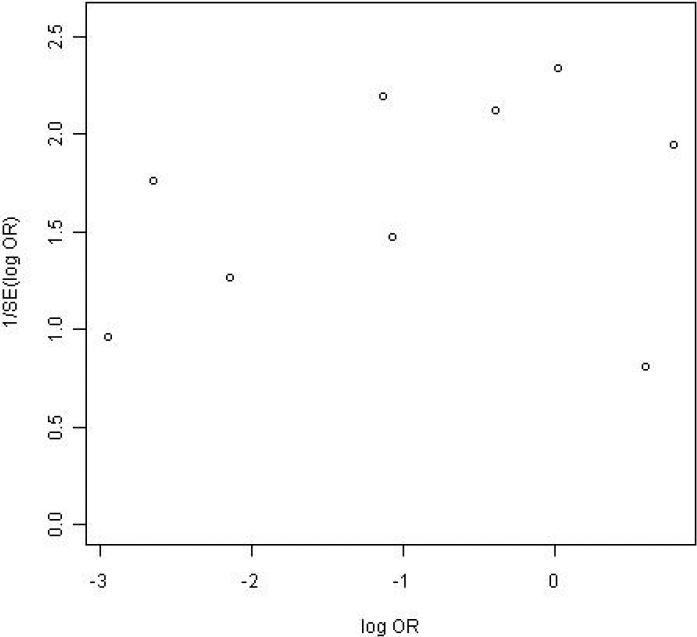

The treatment effect was computed using the pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence limits for prep quality (excellent, good, fair, and poor) and for the proportions of subjects completing the prep. Weighted proportions for each outcome were derived using the inverse of the variance for each trial. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with Woolf's test 21. Funnel plots, which plot the inverse of the standard error of the log-odds ratio against the log-odds ratio, were used to look for evidence of publication bias. All calculations were performed using r-meta library (version 2.14) for the statistical software R (version 2.5.1).

RESULTS

Descriptive and qualitative assessment

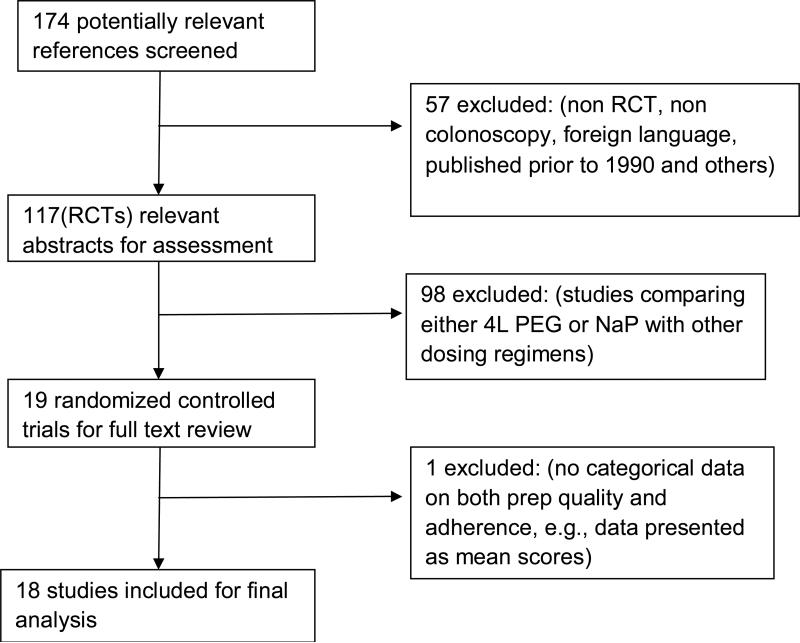

The MEDLIINE and EMBASE databases identified 174 abstracts from 1990-2008. We excluded 57 because they were trials where colonoscopy was not used (n=11), were published in foreign language (n=8), were not randomized trials (n=13), or were trials published prior to 1990 (n=18) and others (n=7). Of the 117 abstracts that described randomized controlled trials, we excluded 98 trials that compared either PEG or NaP to other dosing regimens of the same prep. Of 19 trials included for full text review, we excluded one trial 22 because it contained no data on either prep quality or patient adherence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart diagram of the studies identified for the meta-analysis.

For analysis, we included 18 randomized controlled trials 9, 14-16, 23-36 involving 2,792 patients. Descriptive data for each trial is shown in Table 1. Mean age and gender distribution were similar for the 4L PEG and NaP solution groups. All trials were investigated-blinded and used comparable rating scales for bowel prep quality 9: excellent: small volume of clear liquid or greater than 95% of surface seen; good: large volume of clear liquid covering 5% to 25% of the surface but greater than 90% of surface seen; fair: some semi-solid stool that could be suctioned or washed away but greater than 90% of surface seen; poor: semi-solid stool that could not be suctioned or washed away and less than 90% of surface seen. Of the 18 trials, 10 trials described prep quality in greater detail or in finer gradations (excellent, good, fair, poor) rather than just reporting it as a cumulative measure (excellent/good and fair/poor).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| No | Year/1st author/ref.no |

Study population | Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria | Total number analyzed |

Prep | N per group |

Mean age |

Male/ Female |

Unable to complete prep (%) |

Prep Quality |

Conclusions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent (%) |

Good (%) |

Exce / Good (%) |

Prep Quality |

Prep Completion |

|||||||||||

| 1 | Vanner 199014 | Consecutive patients for elective colonoscopy | Polyps 56%, IBD 12%, bleeding 3%, others 29 % | Creatinine 2.3 mg/dL, symptomatic CHF, massive ascites, MI within 6 months | 102 | NaP sol | 54 | 52 | 30/24 | 0 | 26 | 54 | 80 | NaP better | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 48 | 58 | 25/23 | 20 | 6 | 27 | 33 | ||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | Kolts 199315 | Consecutive outpatients | Polyps 45%, GI bleed 32%, anemia 4%, diarrhea 4%, constipation 4%, other 11% | Unstable CV status, MI, CVA < 2 mo, creatinine > 2 mg/dL, massive ascites, active IBD, active diverticulitis, delayed gastric emptying | 72 | NaP sol | 34 | 52 | 7/27 | 1 | 38 | 41 | 79 | NaP better | NaP=PEG |

| 4L PEG | 38 | 58 | 20/18 | 5 | 32 | 29 | 61 | ||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Marshall 199329 | Consecutive, non-emergent patients | Not stated | Symptomatic CHF, recent MI, creatinine ≥ 2.3 mg/dL, ascites | 143 | NaP sol | 70 | 57.2 | 64/79 for both groups | 13 | 39 | 30 | 69 | NaP=PEG | NaP=PEG |

| 4L PEG | 73 | 57.2 | 18 | 47 | 23 | 70 | |||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | Cohen 199416 | Elective colonoscopy; age/sex–matched | Not stated | Not stated | 422 | NaP sol | 143 | 66.5 | 74/69 | 3 | 65 | 25 | 90 | NaP better | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 279 | 66.7 | 141/138 | 28 | 43 | 25 | 68 | ||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | Golub 1995†36 | Consecutive, ambulatory patients matched for age/sex/indication | Polyps 62%, bleeding 15%, cancer 13%, family history 3%, other 8% | Not stated | 230 | NaP sol | 106 | 58.4 | NA | 1 | 46 | 43 | 89 | NaP=PEG | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 124 | 58.4 | NA | 15 | 48 | 37 | 85 | ||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | Chia 199531 | Elective colonoscopy | Not stated | > 60 years of age, pregnant, history of renal or cardiac diseases, acute IBD and intestinal obstruction | 79 | NaP sol | 39 | 47.7 | 20/19 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 85 | NaP better | NaP=PEG |

| 4L PEG | 40 | 53.2 | 15/25 | 63 | |||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | Henderson 199532 | Outpatient, elective colonoscopies | Not stated | Symptomatic CHF, recent MI, creatinine > 2 mg/dL, ascites | 157 | NaP sol | 51 | 51 | 107/111 for both groups | 1 | Not specified | Not specified | 91 | NaP=PEG | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 106 | 51 | 10 | 92 | |||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | Thompson 199628 | Outpatient colonoscopy | Not stated | Ischemic chest pain, MI, TIA/CVA in last 6 months, creatinine > 200 μg/L, ascites, CHF, colostomy, AMS | 116 | NaP sol | 61 | 72 | 47/14 | 3 | 20 | 46 | 66 | NaP better | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 55 | 70 | 38/17 | 2 | 15 | 44 | 58 | ||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 9 | Clarkston 199627 | Outpatient colonoscopy | Not stated | Severe CHF, creatinine ≥ 2.3 mg/dL, prior bowel resection | 98 | NaP sol | 49 | 57 | 22/27 | 4 | 45 | 36 | 81 | NaP=PEG | NaP=PEG |

| 4L PEG | 49 | 57 | 12/37 | 27 | 31 | 50 | 81 | ||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 10 | Lee 199926 | Consecutive outpatients | Not stated | Not stated | 159 | NaP sol | 71 | 51.5 | 79/80 | 4 | 40 | 31 | 71 | NaP=PEG | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 88 | 57.9 | for all | 11 | 43 | 31 | 74 | ||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 11 | Aronchick 20009 | Outpatient colonoscopy | Not stated | CHF, chronic renal failure, megacolon, severe constipation, partial or subtotal colectomy, or pre-existing electrolyte abnormalities. | 206 | NaP sol | 106 | 60.3 | 46/60 | 1 | 77 | 9 | 86 | NaP=PEG | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 100 | 58.8 | 52/48 | 12 | 66 | 16 | 82 | ||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | Arezzo 200030 | Consecutive patients | Not stated | Not stated | 200 | NaP sol | 100 | 61.9 | 45/55 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 68 | NaP better | NaP=PEG |

| 4L PEG | 100 | 60.5 | 52/48 | 50 | |||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 13 | Seinela 200325 | Consecutive patients | Age > 80 years | Creatinine 2.3 mg/dL, CHF, massive ascites, MI, bowel resection | 72 | NaP sol | 37 | 84 | 1o/62 | Not specified | 48 | 33 | 81 | NaP=PEG | NaP=PEG |

| 4L PEG | 35 | 84 | for all | 52 | 26 | 78 | |||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 14 | Law 2004¶24 | Elective colonoscopy | Age > 18 years | Intestinal obstruction, delayed gastric emptying, creatinine >0.2 mmol/L, CHF, MI in the last 6 months, massive ascites and pregnancy. | 207 | NaP sol | 101 | 58.1 | NA | Not specified | 15 | 50 | 65 | NaP better | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 106 | 58.1 | NA | 12 | 47 | 59 | |||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 15 | Hwang 200523 | Elective colonoscopy | Not stated | Symptomatic CHF, MI, creatinine >1.5 mg/dL, abnormal elevation of transaminases, ileus, bowel obstruction, gastric retention, uncontrolled HTN, unstable angina, pregnancy or breast feeding and severe constipation. | 78 | NaP sol | 38 | 52.2 | 18/22 | Not specified | 58 | 21 | 79 | NaP=PEG | NaP=PEG |

| 4L PEG | 40 | 52.4 | 25/15 | 55 | 28 | 83 | |||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 16 | Bektas 200533 | Elective colonoscopy | Not stated | Creatinine > 2 mg/dL, pregnancy, bowel obstruction, symptomatic CHF, MI in last 3 months, emergent colonoscopy, acute IBD, ascites | 97 | NaP sol | 61 | 56.7 | 29/32 | Not specified | 52 | 38 | 90 | NaP=PEG | NaP better |

| 4L PEG | 36 | 54.3 | 13/23 | 47 | 44 | 91 | |||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 17 | Huppertz-Hauss 2005¶34 | Consecutive outpatients for colonoscopy | Not stated | < 18 years, creatinine> 150mmol/L, CHF, hepatic failure, electrolyte abnormalities, | 160 | NaP sol | 84 | 58.6 | 43/41 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 85 | NaP=PEG | NaP=PEG |

| 4L PEG | 76 | 57.4 | 29/47 | 81 | |||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||

| 18 | Rostom 2006†35 | Elective colonoscopy | patients 18-80 years old | Renal failure, unstable angina, acute coronary syndrome, CHF, ascites, megacolon, bowel obstruction, previous bowel resection and evaluation of diarrhea | 194 | NaP sol | 144 | 52 | 39/95 | 8 | Data presented as mean scores | NaP better | NaP better | ||

| 4L PEG | 50 | 55 | 16/34 | 21 | |||||||||||

Congestive heart failure-CHF, Myocardial infarction -MI, Acute coronary syndrome-ACS, Hypertension-HTN, Inflammatory bowel diseases-IBD, Altered mental status-AMS, Transient ischemic attack-TIA, Cerebrovascular attack-CVA.

Trials not included in prep completion analysis as there was no data available.

Trials not included in prep quality analysis as the data was either presented as mean scores or not available.

The methods of preparation of PEG and NaP were similar among the trials, with minor variation in the timing of prep consumption. Dietary recommendations on the day prior to colonoscopy varied from a regular diet to a clear liquid diet for lunch to a full clear liquid diet in the evening. In total, we found the trials to be similar enough in study design, study populations, interventions and outcomes to combine them quantitatively.

Quantitative assessment

There was statistically significant heterogeneity for the outcomes of prep quality and inability to complete the prep (P value for excellent/ good prep quality = 0.0003; P value for inability to complete the prep < 0.0001), indicating that there was greater-than- expected statistical variation among the trials for both outcomes 37.

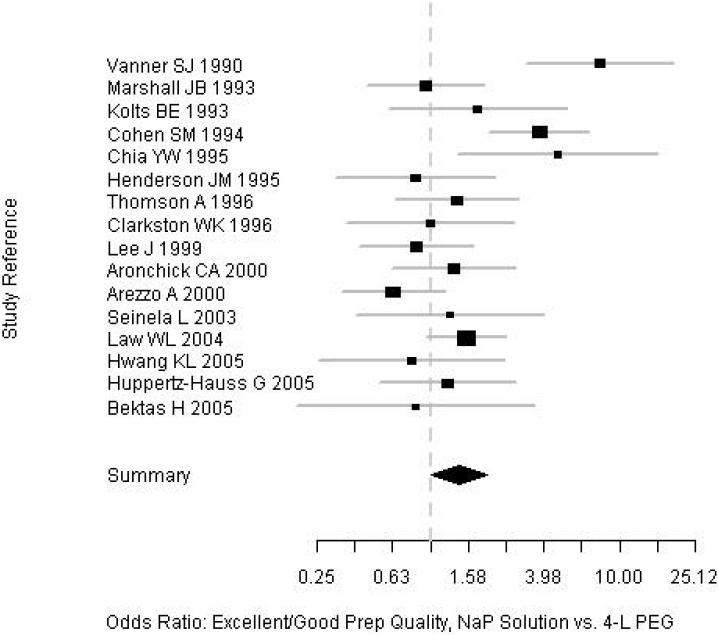

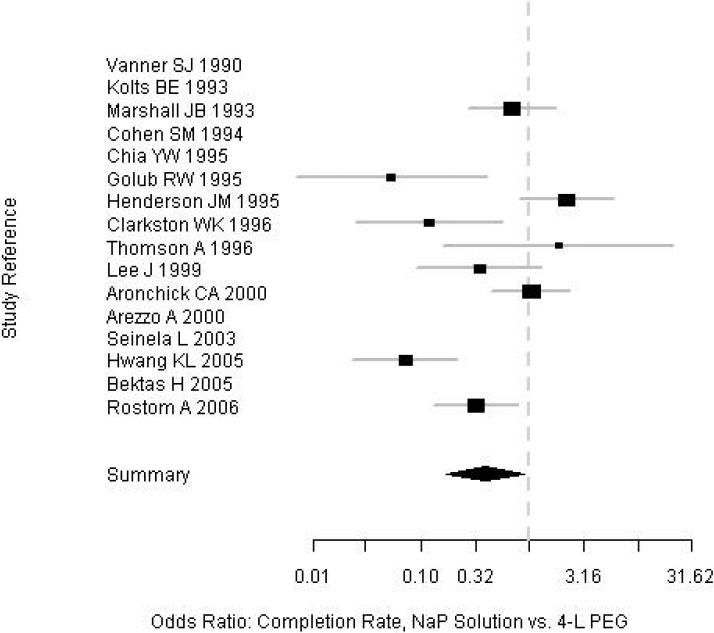

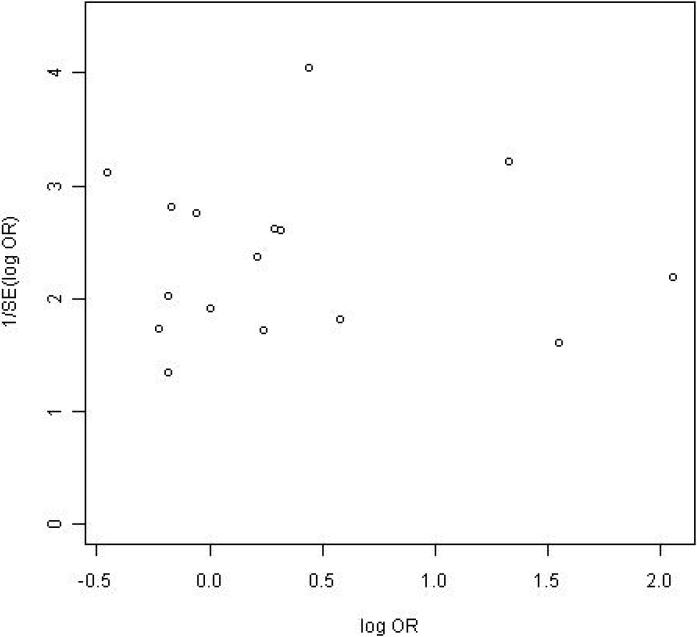

Subjects who received NaP were more likely to have an excellent or good quality prep than were those who received PEG (82% vs. 77%; OR=1.43; 95% CI, 1.01-2.00). Among a subgroup of 10 trials in which prep quality was reported in greater detail between NaP and PEG, there were no significant differences in the proportions of patients with any specific level of prep quality: excellent (34% vs. 27%), good (30% vs. 30%), fair (17% vs. 17%), and poor (4.7% vs. 7.7%) (Table 2, Figure 2). Among the nine trials that assessed prep completion rates (Table 2, Figure 3), patients receiving NaP solution were more likely to complete the preparation than patients receiving 4-L PEG (3.9% vs. 9.8%, respectively, did not complete the preparation; OR= 0.40; CI, 0.17-0.88). Serious adverse effects were not described for either prep among the trials. Funnel plots for both outcomes reveal no clear evidence of publication bias (Figures 4 and 5).

Table 2.

Comparison of percent completion and prep quality: 4L PEG vs. NaP

| Outcome | Study N | NaP | 4L PEG | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Heterogeneity P-value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unable to complete | 9 | 3.90% | 9.83% | 0.40 (0.17-0.88) | <0.0001 |

| Execellent / good quality | 16 | 82.42% | 77.03% | 1.43 (1.01-2.0) | 0.0003 |

| Excellent quality | 10 | 33.94% | 26.86% | 1.26 (0.94-1.7) | 0.23 |

| Good quality | 10 | 30.44% | 29.69% | 1.12 (0.8-1.56) | 0.065 |

| Fair quality | 10 | 16.60% | 17.40% | 0.78 (0.59-1.04) | 0.671 |

| Poor quality | 9 | 4.70% | 7.74% | 0.67 (0.36-1.23) | 0.046 |

P-value from the Woolf's test for heterogeneity.

Figure 2.

Forrest plot of prep quality among the trials.

Figure 3.

Forrest plot of prep completion among the trials.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of prep quality.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of prep completion.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials comparing NaP solution and 4L PEG shows that NaP solution is more likely than 4 L PEG both to be completed by patients and to result in an excellent or good quality prep. Although there were no differences in any specific level of prep quality between NaP solution and 4L PEG among those trials in which prep quality was reported in finer detail, the trends in the data indicate a higher proportion of NaP patients with excellent quality prep and a lower proportion with poor quality prep.

Previous meta-analyses of head-to-head trials of PEG vs. NaP have reported that NaP is more effective, better tolerated, and less costly than PEG 6, 19. However, in 2007 a meta-analysis by Belsey et al reported that no single bowel preparation was consistently superior to the others 18. To incorporate all the available evidence, we included trials that were either not included in previous analyses or that were more recently published 9, 23, 30, 33, 35.

This analysis has several strengths. First, our literature search was comprehensive in scope, and identified all relevant studies. Second, we included only randomized trials, which are considered to be superior to non-randomized comparisons. Third, the trials were very similar in study population recruited, in how the interventions (i.e., preps) were administered, and in the way outcomes were measured. Although the trials were statistically heterogeneous, they were clinically homogeneous from a qualitative standpoint. Fourth, we used a random effects model, which provides conservative quantitative results. Lastly, we found no clear evidence of publication bias, as supported by funnel plots.

Limitations of this analysis deserve comment. The potential for statistical heterogeneity is always present when combining trials quantitatively, and to address this issue, we assessed the trials qualitatively and determined that they were clinically similar enough to perform meta-analysis. We used a random effects model in the analysis, which provides a more conservative result with wider confidence intervals. Several factors may contribute to clinical and/or methodological heterogeneity among trials. One factor is variation in timing of bowel prep. The time at which the bowel prep was started was not uniform among the trials ranging from 48 hours 25 to 12 hours before the scheduled procedure. This was an issue, particularly for patients undergoing the procedure in the afternoon, as it may have an effect on prep quality 30, 36. Some of the trials did not provide information about timing of the prep 34, 35.

Another factor potentially contributing to heterogeneity is variation in dietary instructions prior to and during the prep, which also were not uniform among the trials, and which ranged from a regular diet to a clear liquid diet for lunch and clear liquid diet in the evening. A third possible factor is the use of adjunctive liquids consumed during the prep.

In contrast to previous meta-analyses on this topic 6, 18, 19, we did not include an assessment of study quality. One reason for not doing so was that, based on our initial reading of the included trials, we thought they were very similar in design, with comparable study populations, interventions, and outcomes. In this case, we would have expected little variation in study quality. Secondly, there is no consensus on how best to use study quality in the quantitative part of a systematic review. Choices are to exclude the lowest quality trials, weight each study's quantitative results by a factor reflective of its quality, or stratify quantitative results based on a cut point in the quality score. While it remains unproven, our impression is that assessing and incorporating study quality would likely have had little effect on the quantitative results.

In recent years, there have been case series of renal insufficiency due to nephrocalcinosis with use of NaP for colonoscopy preparation. A total of 37 cases have been reported over a 4-year period, 4 of which progressed to end stage renal disease requiring dialysis 38-41. The majority of these patients had one or more of the following co-morbid conditions: diabetes mellitus, hypertension treated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) or diuretics, preexisting renal insufficiency, older age; small bowel disease (that resulted in calcium and vitamin D malabsorption). Renal biopsies of many of the reported cases have showed nephrocalcinosis with intratubular deposition of calcium-phosphate. The term for this pathologic condition is acute phosphate nephropathy (APN).The histopathology suggests that sodium phosphate ingestion leads to obstructive calcium-phosphate crystalluria followed by acute intratubular nephrocalcinosis. These reports raised concerns that led Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 42 to announce a safety alert in December 2008 stating that a Boxed Warning was to be added to the labeling on prescription oral phosphate solutions (Visicol and OsmoPrep). The FDA further recommended against the use of over the counter oral solution phosphate products for bowel preparation. Shortly after this announcement, all over-the-counter NaP products were voluntarily removed from the market, with a subsequent sharp decline in use of NaP solution.

Despite the FDA's action and resulting reaction, the published data suggest that absolute risk of APN is very low 43, 44. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of seven controlled studies (patient N=14,520) of the effects of NaP versus comparator on kidney function showed that there was significant clinical heterogeneity in the populations studied, study methods, definition of kidney injury, and results45. Quantitatively, the pooled odds ratio for kidney injury among NaP-treated patients ranged from 1.08 (CI, 0.71-1.62) to 1.22 (CI, 0.77-1.92), neither of which is statistically significant. The investigators concluded that it was not possible to discern whether there is a true association between NaP and kidney injury. In addition, an appropriate dosing interval of 10-12 hours in between doses of NaP may reduce the risk for APN46.

The results of this meta-analysis apply to patients undergoing elective colonoscopy who do not have a history of co-morbid conditions like renal insufficiency, recent myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure; particularly NaP should not be used in patients suspected or with inflammatory bowel diseases because of the apthous ulcerations it may cause resulting in complexity in interpreting endoscopic and histological findings47, 48. Physicians should be aware of the risk of acute kidney injury with NaP preparations and should avoid its use in elderly patients and in those with preexisting renal insufficiency. In addition, NaP should be used with caution in patients on medications that can affect volume status or renal function (diuretics, ACE-I or ARBs). Further, all patients should be encouraged to adequately hydrate themselves prior to and while using NaP preparations. With the recent FDA safety alert, over the counter OSPs should not be used for bowel preparation, although they are still available for treatment of constipation. Despite the current restriction on use of NaP solution, up to nearly 75% of the patients undergoing elective colonoscopy are eligible to receive NaP preparation, given the fact that the tablet form is available by prescription49.

In conclusion, among 18 head-to-head randomized trials of NaP solution vs. 4 L PEG, NaP solution was more likely to be completed by patients and to result in excellent or good quality prep. If and when NaP solution is once again made available for bowel preparation, this analysis may have direct implications for patient care.

Acknowledgements

Supported by in part by NIH grant # DK K24 02756 (TFI). Authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Seeff LC, Richards TB, Shapiro JA, et al. How many endoscopies are performed for colorectal cancer screening? Results from CDC's survey of endoscopic capacity.[see comment]. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(6):1670–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers J-J, Burnand B, Vader J-P. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;61(3):378–84. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P, Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2003;58(1):76–9. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson FB, Korman MG, Nicholson FB, Korman MG. Acceptance of flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy for screening and surveillance in colorectal cancer prevention. J Med Screen. 2005;12(2):89–95. doi: 10.1258/0969141053908294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis GR, Santa Ana CA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Development of a lavage solution associated with minimal water and electrolyte absorption or secretion. Gastroenterology. 1980;78(5 Pt 1):991–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu CW, Imperiale TF. Meta-analysis and cost comparison of polyethylene glycol lavage versus sodium phosphate for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1998;48(3):276–82. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiPalma JA, Brady CE, 3rd, Stewart DL, et al. Comparison of colon cleansing methods in preparation for colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1984;86(5 Pt 1):856–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas G, Brozinsky S, Isenberg JI. Patient acceptance and effectiveness of a balanced lavage solution (Golytely) versus the standard preparation for colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1982;82(3):435–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, Dufrayne F, Bergman G. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2000;52(3):346–52. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radaelli F, Meucci G, Imperiali G, et al. High-dose senna compared with conventional PEG-ES lavage as bowel preparation for elective colonoscopy: a prospective, randomized, investigator-blinded trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(12):2674–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fordtran JS, Santa Ana CA, Cleveland Mv B. A low-sodium solution for gastrointestinal lavage. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(1):11–6. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91284-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes A, Buffum M, Fuller D. Bowel preparation comparison: flavored versus unflavored colyte. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003;26(3):106–9. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(7):1696–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanner SJ, MacDonald PH, Paterson WG, Prentice RS, Da Costa LR, Beck IT. A randomized prospective trial comparing oral sodium phosphate with standard polyethylene glycol-based lavage solution (Golytely) in the preparation of patients for colonoscopy.[see comment]. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85(4):422–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolts BE, Lyles WE, Achem SR, Burton L, Geller AJ, MacMath T. A comparison of the effectiveness and patient tolerance of oral sodium phosphate, castor oil, and standard electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy preparation.[see comment]. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(8):1218–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen SM, Wexner SD, Binderow SR, et al. Prospective, randomized, endoscopic-blinded trial comparing precolonoscopy bowel cleansing methods. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37(7):689–96. doi: 10.1007/BF02054413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frommer D. Cleansing ability and tolerance of three bowel preparations for colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(1):100–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02055690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: oral bowel preparation for colonoscopy.[see comment]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(4):373–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan JJ, Tjandra JJ, Tan JJY. Which is the optimal bowel preparation for colonoscopy - a meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(4):247–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R. Combining evidence from clinical trials. Anesth Analg. 1990;70(5):475–6. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199005000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woolf B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. . Ann. Human Genet. (London) 1955;19:251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1955.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kossi J, Kontula I, Laato M. Sodium phosphate is superior to polyethylene glycol in bowel cleansing and shortens the time it takes to visualize colon mucosa. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(11):1187–90. doi: 10.1080/00365520310006180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang K-L, Chen WT-L, Hsiao K-H, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol lavage for colonoscopy preparation. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(47):7486–93. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i47.7486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Law W-L, Choi H-K, Chu K-W, Ho JWC, Wong L. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial comparing polyethylene glycol solution, one dose and two doses of oral sodium phosphate solution. Asian J. 2004;27(2):120–4. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seinela L, Pehkonen E, Laasanen T, Ahvenainen J. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy in very old patients: a randomized prospective trial comparing oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(2):216–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J, McCallion K, Acheson AG, Irwin ST. A prospective randomised study comparing polyethylene glycol and sodium phosphate bowel cleansing solutions for colonoscopy. Ulster Med J. 1999;68(2):68–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarkston WK, Tsen TN, Dies DF, Schratz CL, Vaswani SK, Bjerregaard P. Oral sodium phosphate versus sulfate-free polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution in outpatient preparation for colonoscopy: a prospective comparison. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1996;43(1):42–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomson A, Naidoo P, Crotty B. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a randomized prospective trail comparing sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol in a predominantly elderly population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11(2):103–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall JB, Pineda JJ, Barthel JS, King PD. Prospective, randomized trial comparing sodium phosphate solution with polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1993;39(5):631–4. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arezzo A. Prospective randomized trial comparing bowel cleaning preparations for colonoscopy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10(4):215–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chia YW, Cheng LC, Goh PM, et al. Role of oral sodium phosphate and its effectiveness in large bowel preparation for out-patient colonoscopy. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1995;40(6):374–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson JM, Barnett JL, Turgeon DK, et al. Single-day, divided-dose oral sodium phosphate laxative versus intestinal lavage as preparation for colonoscopy: efficacy and patient tolerance.[see comment]. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1995;42(3):238–43. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bektas H, Balik E, Bilsel Y, Yamaner S, Bulut T, Bugra D, Buyukuncu Y, Akyuz A, Sokucu N. Comparison of sodium phosphate, polyethylene glycol and senna solutions in bowel preparation: A prospective, randomized controlled clinical study. Digestive Endoscopy. 2005;17(4):290–296. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huppertz-Hauss G, Bretthauer M, Sauar J, et al. Polyethylene glycol versus sodium phosphate in bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2005;37(6):537–41. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rostom A, Jolicoeur E, Dube C, et al. A randomized prospective trial comparing different regimens of oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol-based lavage solution in the preparation of patients for colonoscopy.[see comment]. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2006;64(4):544–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golub RW, Kerner BA, Wise WE, Jr., et al. Colonoscopic bowel preparations--which one? A blinded, prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(6):594–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02054117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.L'Abbe KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K. Meta-analysis in clinical research. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1987;107(2):224–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desmeules S, Bergeron MJ, Isenring P, Desmeules S, Bergeron MJ, Isenring P. Acute phosphate nephropathy and renal failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(10):1006–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200309043491020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonlusen G, Akgun H, Ertan A, et al. Renal failure and nephrocalcinosis associated with oral sodium phosphate bowel cleansing: clinical patterns and renal biopsy findings. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(1):101–6. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-101-RFANAW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, Radhakrishnan J, et al. Acute phosphate nephropathy following oral sodium phosphate bowel purgative: an underrecognized cause of chronic renal failure. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2005;16(11):3389–96. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markowitz GS, Perazella MA. Acute phosphate nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2009;76(10):1027–34. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.FDA Safety Alert: Oral Sodium Phosphate (OSP) Products for Bowel Cleansing (December) 2008.

- 43.Hookey LC, Depew WT, Vanner S, Hookey LC, Depew WT, Vanner S. The safety profile of oral sodium phosphate for colonic cleansing before colonoscopy in adults.[see comment]. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2002;56(6):895–902. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singal AK, Rosman AS, Post JB, Bauman WA, Spungen AM, Korsten MA. The renal safety of bowel preparations for colonoscopy: a comparative study of oral sodium phosphate solution and polyethylene glycol.[see comment]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(1):41–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunelli SM, Brunelli SM. Association between oral sodium phosphate bowel preparations and kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2009;53(3):448–56. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dominitz JA. Take two phosphasodas and scope them in the morning. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Zwas FR, Cirillo NW, el-Serag HB, Eisen RN. Colonic mucosal abnormalities associated with oral sodium phosphate solution.[see comment]. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1996;43(5):463–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watts DA, Lessells AM, Penman ID, et al. Endoscopic and histologic features of sodium phosphate bowel preparation-induced colonic ulceration: case report and review. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2002;55(4):584–7. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imperiale TF, Sherer E, Balph JA, Cardwell J, Qi A. Safety and Effectiveness of a Computer-based Decision Tool (DT) for Tailoring Preparation for Colonoscopy (CY). SGIM. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]