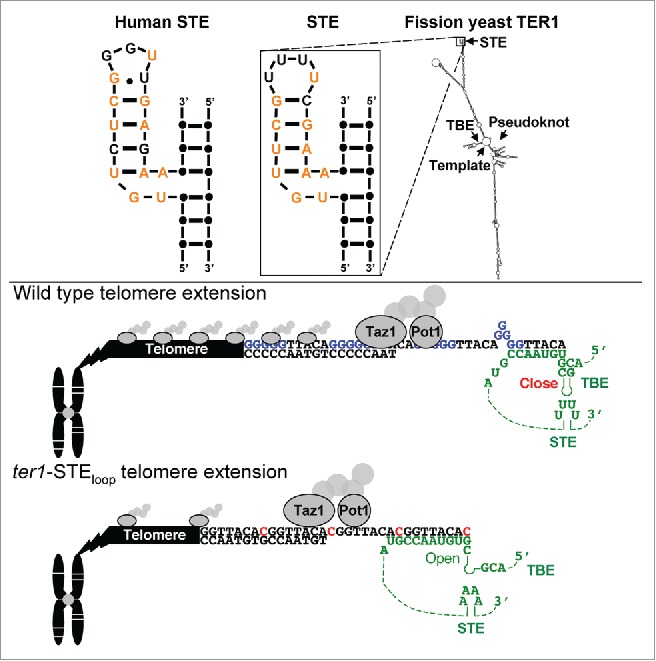

The “end replication problem,” the inability of conventional DNA polymerases to duplicate the very ends of linear DNA molecules, is usually solved by telomerase, a specialized reverse transcriptase. The telomerase holoenzyme consists of the catalytic subunit (TERT), a telomerase RNA (TER) and species-specific accessory factors. Although telomerase RNAs vary enormously in size and nucleotide sequence, 4 structures are highly conserved: (1) a telomere repeat templating sequence, which is single-stranded in the folded RNA; (2) a template boundary element (TBE) helix that is immediately adjacent to the template and prevents synthesis past the template; (3) a pseudoknot that affects template usage, and (4) the stem terminus element (STE), which was discovered in mammals in 2000 where it is essential for telomerase activity in vitro and in vivo1 yet its mode of action was previously unknown. Except for the STE, the 3 other elements are in the catalytic core region of the RNA. This review summarizes a recent paper that takes advantage of the conservation of STE sequence and structure in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Fig. 1) to reveal the function of the STE.

Figure 1.

The fission yeast stem terminus element (STE) enforces telomere repeat sequence identity. Fission yeast telomerase RNA (TER) has 4 conserved structural elements: STE, template, TBE (template boundary element) and pseudoknot. The conserved STE nucleotides are indicated (orange). During wild type telomere extension the STE in telomerase RNA (green) facilitates the base-paired structure of the TBE helix, which prevents rare cytosine insertion. When the TBE is functional, the stuttering reaction that introduces guanine tracts (blue) occurs. The DNA binding shelterin proteins (gray) Taz1 and Pot1 bind normally to WT telomeric DNA. By contrast, the TER1-STEloop mutant does not support full TBE function, which allows reverse transcription to extend into the TBE helix. The open helix encodes rare cytosines (red) that prevent template stuttering and guanine tract incorporation. The resulting ter1-STEloop aberrant telomere repeats bind reduced levels of Taz1 and Pot1.

To understand how the STE works, we generated a panel of fission yeast STE mutants and determined their effects on telomere length2. This characterization showed that, as in mammals, the fission yeast STE is essential for telomerase activity and telomere maintenance and identified a partial-loss-of-function allele, ter1-STEloop. In this mutant, the 4 tandem uridines in the STE tetraloop are changed to adenines (Fig. 1). Because telomeres are short but stable in ter1-STEloop cells, the mutant was ideal for analyzing STE function in vivo.

Although non-canonical telomere repeats are seen in most organisms, fission yeast telomeric DNA is particularly heterogeneous, as reflected in its consensus sequence, 5′-(G)0–6GGTTACAC-3′ (the rare cytosine, discussed below, is underlined). Our ability to isolate the ter1-STEloop allele was probably facilitated by this heterogeneity, which arises from the inefficiency of the fission yeast TBE, which is less capable than TBEs in other organisms at preventing run-on reverse transcription3,4. In wild type fission yeast, occasional TBE failure results in reverse transcription into the TBE, which introduces a rare cytosine at the end of the core telomere sequence in about 12% of repeats. The variable number of guanine residues is generated by “stuttering” that arises from the absence of base-pairing between the RNA template and the telomeric DNA end. Because incorporation of the rare cytosine changes the template RNA-telomeric DNA register, its addition results in reduced stuttering and hence fewer guanine-tracts (Reviewed in5).

Although we considered that the STE promotes holoenzyme formation, TERT association with TER1 was unaffected in ter1-STEloop cells. Likewise, the physical interaction between telomerase and the telomere was normal. However, as in humans, telomerase catalysis is compromised1 as extracts from ter1-STEloop cells had very low activity. We isolated and cloned telomeric DNA from mutant and wild type cells and determined their sequence. For cloning, we developed a novel method that exploited the rapid but reversible telomere shortening that occurs by growing fission yeast cells at higher temperatures. This approach ensured that we analyzed only the sequence templated by TER1-STEloop. Surprisingly, ter1-STEloop telomeric DNA does not have wild type sequence. Rather, the mutant telomeres have a much higher frequency of rare cytosines and reduced frequency of guanine tracts, 2 phenotypes first seen in cells with mutant TBEs3,4 (Fig. 1). The unusual sequence of ter1-STEloop telomeric DNA was recombination independent but telomerase dependent. Thus, the STE affects how the telomerase catalytic core templates nucleotide addition. Because the ter1-STEloop mutation affects the sequence of telomeric DNA in the same way as mutations that disrupt TBE function, we conclude that the STE enforces TBE activity.

The TER1-STEloop templated change in telomeric sequence also affected telomeric chromatin. In fission yeast and mammals, telomeres are bound by the multi-subunit shelterin complex, which together with the telomeric DNA, protects telomeres and mediates all telomere functions. Using chromatin immunoprecipitaton, we analyzed telomere binding of Taz1 and Pot1, the 2 shelterin components that bind telomeric DNA directly. The telomere association of both proteins is significantly reduced in ter1-STEloop cells. Thus, owing to its effects on telomere sequence, the STE is essential for proper shelterin assembly.

The ability of the STE to alter TBE function and change telomere repeat addition is the first example in any organism of a region outside of the template-TBE core that changes the sequence of telomeric DNA. This result is particularly surprising given that the STE is far from the template-TBE region in the linear structure of the RNA (Fig. 1). However, these results are consistent with in vitro cross-linking experiments with the human TER that showed long range interactions between the STE and the end of the template 6. Based on this result and the similar effects of human and fission yeast STE mutants on telomere length and in vitro telomerase activity, the human STE likely acts similarly to prevent run-on reverse transcription and enforce the sequence of human telomeric DNA. Consequently, the STE is a good candidate for therapeutics that target telomerase action. An engineered molecule able to alter STE activity in telomerase expressing cancer cells could corrupt the regular human telomere repeats, impair shelterin binding to accelerate loss of telomere functions and trigger apoptosis.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Mitchell JR, Collins K. Mol Cell 2000; 6:361-71; PMID:10983983; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00036-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webb CJ, Zakian VA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:11312-7; PMID:26305931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1503157112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webb CJ, Zakian VA. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008; 15:34-42; PMID:18157149; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Box JA, et al. A flexible template boundary element in the RNA subunit of fission yeast telomerase. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:24224-33; PMID:18574244; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M802043200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ares M Jr., Chakrabarti K. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008; 15:18-9; PMID:18176550; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb0108-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueda CT, Roberts RW. RNA 2004; 10:139-47; PMID: 14681592; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.5118104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]