Senescence is a cellular response to stresses such as oncogenic signaling, DNA damage and telomere loss, characterized by a stable growth arrest. The importance of senescence as a safeguard against malignant transformation has been broadly studied for over 10 y. More recently, senescence has also been implicated in numerous other biological processes, wherein senescence may be beneficial, such as for maintenance of tissue homeostasis or detrimental such as in organismal aging and, paradoxically, cancer progression. These detrimental effects are primarily driven by the secretion by senescent cells of a collection of factors that include cytokines and chemokines with pro-inflammatory properties, as well as various growth factors and proteases. Collectively, this is known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Given its heterogeneity, identifying master regulators of the SASP that are druggable may facilitate therapeutic intervention. It has been known for a while that mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) regulates the SASP.1,2 However, the details and implications of this regulation have not been clarified until now. Two recent manuscripts, from Campisi and colleagues3 and our group,4 have proposed molecular mechanisms by which inhibition of mTOR suppresses the SASP.

mTOR is a kinase that promotes mRNA translation and protein synthesis through the phosphorylation of at least 2 different substrates, S6 kinases (S6Ks) and eIF4E binding proteins (4EBPs). Although both we (unpublished data) and Laberge et al.3 found that the mTOR-S6K axis can control the SASP, the role of 4EBP seems more prominent. mTOR can differentially control the translation of specific mRNAs with 5′ terminal oligopyrimidine (TOP) motifs via 4EBPs.5 Therefore, we explored whether mTOR differentially regulates the translation of one or more SASP components. Interestingly, we both found that IL1α was the SASP component whose translation was affected the most upon mTOR inhibition.3,4 During oncogene-induced senescence however, a big proportion of IL1α continued being translated after mTOR inhibition, suggesting that mTOR might regulate the SASP by other means. Indeed, we found that translation of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAPK2) was tightly controlled by mTOR and responsible for SASP regulation.4

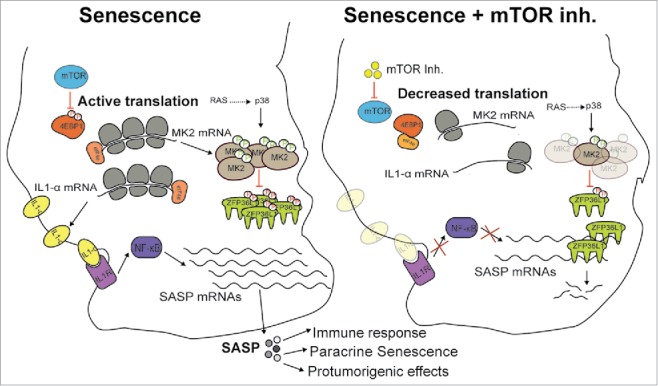

Our study reveals that mTOR ultimately regulates the SASP by controlling mRNA stability. Inhibition of mTOR suppresses the SASP by specifically downregulating MAPKAPK2 translation via 4EBP1. In senescence, MAPKAPK2 phosphorylates and inhibits ZFP36L1, an mRNA-binding protein involved in AU-rich element (ARE)-mediated decay that targets SASP components. Therefore, mTOR inhibition leads to activation of ZFP36L1 and subsequent degradation of the mRNAs of SASP components (Fig. 1). In fact, the effect of expressing a ZFP36L1 mutant protein (resistant to MAPKAPK2 phosphorylation) in senescent cells was striking, since the expression of more than 60% of the SASP mRNAs decreased significantly. Considering that AREs are found only in a small proportion (around 5–8%) of all mRNAs, our data suggest that ZFP36L1 is an important SASP regulator. Moreover, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that the top 15 signatures antagonized by ZFP36L1 are related to inflammatory responses and cytokine-related phenotypes. To investigate if the effect of ZFP36L1 was linked to the presence of AREs, we used an algorithm termed AREScore that identifies AREs and provides a numerical assessment of their strength.6 We observed a very consistent correlation between AREscore and sensitivity to ZFP36L1 that suggest that AREscores can be used as a predictor of ZFP36L1 function. Our findings open up many interesting prospects regarding the therapeutic potential of ZFP36L1 within a wide range of pathologies such as fibrosis or cancer. A potential role for ZFP36L1 in tumor-stroma interactions and chemoresistance mechanisms is of particular interest.

Figure 1.

mTOR regulates the SASP. In senescent cells, mTOR regulates the SASP by controlling the translation of IL1A and MAPKAPK2. MAPKAPK2 phosphorylates and inhibits the RNA-binding protein ZFP36L1, thereby preventing the degradation of SASP transcripts by ARE-mediated decay. Additionally, IL1α activates NF-κB in a cell-autonomous manner to promote the transcription of SASP genes. Upon mTOR inhibition, ZFP36L1 degrades SASP transcripts and the IL1α feedback loop is abrogated.

Although senescence is a key tumor suppressor mechanism, the SASP can also promote and enhance malignant phenotypes in neighboring tumoral cells. For example, the secretome of senescent cells can promote epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, enhance tumor growth or cause chemoresistance. Importantly, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of mTOR in senescent cells blunted the protumorigenic effects of the SASP without rescuing the growth arrest. Our findings are of particular interest, since one of the most important therapeutic needs in the senescence field is to dissociate the good (tumor suppression via growth arrest) from the bad (tumor progression via SASP) sides of senescence.

Since mTOR is aberrantly activated in well over 50% of human cancers, there has been much interest in using mTOR inhibitors in cancer treatment, mainly to exploit their antiproliferative effects. Our findings shed new light within the mechanisms by which mTOR inhibition may be clinically relevant and could as well improve therapeutic approaches. Finally, it is worth noting that inhibition of the mTOR pathway extends lifespan in model organisms and confers protection against a growing list of age-related pathologies. A common feature of aging tissues is low-level chronic inflammation, termed inflammaging.7 Thus, impairment of the SASP and the subsequent reduction in chronic, age-associated inflammation is an attractive mechanism by which mTORC1 inhibition could slow multiple age-related pathologies in mammals.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Narita M, et al.. Science 2011; 332:966-70; PMID:21512002; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1205407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iglesias-Bartolome R, et al. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 11:401-14; PMID:22958932; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laberge RM, et al.. Nat Cell Biol 2015; 17:1049-61; PMID:26147250; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb3195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herranz N, et al.. Nat Cell Biol 2015; 17:1205-17; PMID:26280535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb3225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thoreen CC, et al. Nature 2012; 485:109-13; PMID:22552098; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spasic M, et al. PLoS Genet 2012; 8:e1002433; PMID:22242014; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franceschi C, et al. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000; 908:244-54; PMID:10911963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]