Abstract

Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) is pivotal for proper mitotic progression, its targeting activity is regulated by precise subcellular positioning and phosphorylation. Here we assessed the protein expression, subcellular localization and possible functions of phosphorylated Plk1 (pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210) in mouse oocytes during meiotic division. Western blot analysis revealed a peptide of pPlk1Ser137 with high and stable expression from germinal vesicle (GV) until metaphase II (MII), while pPlk1Thr210 was detected as one large single band at GV stage and 2 small bands after germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), which maintained stable up to MII. Immunofluorescence analysis showed pPlk1Ser137 was colocalized with microtubule organizing center (MTOC) proteins, γ-tubulin and pericentrin, on spindle poles, concomitantly with persistent concentration at centromeres and dynamic aggregation between chromosome arms. Differently, pPlk1Thr210 was persistently distributed across the whole body of chromosomes after meiotic resumption. The specific Plk1 inhibitor, BI2536, repressed pPlk1Ser137 accumulation at MTOCs and between chromosome arms, consequently disturbed γ-tubulin and pericentrin recruiting to MTOCs, destroyed meiotic spindle formation, and delayed REC8 cleavage, therefore arresting oocytes at metaphase I (MI) with chromosome misalignment. BI2536 completely reversed the premature degradation of REC8 and precocious segregation of chromosomes induced with okadaic acid (OA), an inhibitor to protein phosphatase 2A. Additionally, the protein levels of pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210, as well as the subcellular distribution of pPlk1Thr210, were not affected by BI2536. Taken together, our results demonstrate that Plk1 activity is required for meiotic spindle assembly and REC8 cleavage, with pPlk1Ser137 is the action executor, in mouse oocytes during meiotic division.

Keywords: mouse, MTOC, oocytes, Plk1 phosphorylation, REC8 cleavage, spindle formation

Abbreviations

- GV

germinal vesicle

- GVBD

germinal vesicle breakdown

- pro-MI

pro-metaphase I

- MI

metaphase I

- MII

metaphase II

- MTOC

microtubule organizing center

- SAC

spindle assembly checkpoint

- Plk1

polo-like kinase 1

- pPlk1Ser137

phosphorylated Plk1 on Serine 137

- pPlk1Thr210

phosphorylated Plk1 on Threonine 210

- PP2A

protein phosphatase 2A

- OA

okadaic acid.

Introduction

Chromosome segregation errors in female meiosis can result in embryo genetic instability, which is the leading cause for infertility, spontaneous abortion and congenital birth defects. An understanding of mechanisms of chromosome segregation in female meiosis is of fundamental importance and may contribute to an understanding of human aneuploidy.

During cell division, chromosome congression, alignment and segregation are driven by the microtubule-based machine, spindle apparatus. Defects in spindle structure or function will usually lead to chromosome missegregation. In somatic cells, spindle assembly is regulated by centrosome, which is composed of a pair of orthogonal centrioles and the surrounding amorphous material, named pericentriolar material (PCM).1 Centrioles are required for centrosome structural maintenance and spindle rational orientation.2 In turn, PCM essentially directs microtubule nucleation and anchoring, depending on 2 integral components, γ-tubulin and pericentrin. γ-tubulin combines with several other associated proteins to form γ-tubulin ring complex (γTuRC), which functions as template to initiate and regulate microtubule assembly.3-4 Pericentrin scaffolds the binding of γTuRC and other key factors to centrosome, supporting the orderly formation of microtubule array.5-7 For most mammalian oocytes, the centrioles are eliminated at the early stages of oogenesis,8 and the meiotic spindle formation is regulated by a unique microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs) in a centrosome-independent manner.9 It is still not fully known about the molecular composition and functional regulation mechanism of MTOC in mammalian oocytes. It has been confirmed that γ-tubulin and pericentrin are retained in MTOC during centriole elimination, and definitely required for microtubule assembly in oocytes.10-15 Collecting evidences show that some protein molecules, such as Aurora A kinase (Aur-A), 16-17 protein kinase C (PKC) 18-19 and LIM kinase 1 (LIMK1), 20 etc., are recruited to MTOC during germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), regulating MTOC organization and polar localization. Further investigations are needed to identify the regulatory factors facilitating MTOC maturation after GVBD, and to piece together the interactive network regulating spindle formation in mammalian oocytes.

The stepwise loss of cohesion between chromosomes is another guarantee mechanism for faithful chromosome segregation in oocyte meiosis.21 Cohesion is released between chromatid arms, but sustained in the local space surrounding centromeres during anaphase I, giving rise to the separation of homologous chromosomes but not sister chromatids, and the release of centromeric cohesion permits the segregation of sister chromatids during anaphase II. Premature loss of centromeric cohesion can cause chromosome missegregation.22 The cohesion is achieved by a highly conserved ring-like complex surrounding paired chromosomes, this complex is composed of 4 cohesin subunits: REC8 (meiotic recombination protein), Stag3 (stromal antigen 3) and 2 SMC (structural maintenance of chromosomes) family proteins, SMC1β and SMC3.21,23 The cohesin complex collapses, relieving the binding force that holds chromosomes together, when REC8 is degraded by separase. In addition, REC8 must be phosphorylated by specific upstream kinase before it can be degradable.24-28 During meiosis I, REC8 phosphorylation is resisted at centromere area by protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), so as to maintain effective REC8 accumulation between sister centromeres to ensure sister chromatids are bounded together and behave as one unit until the onset of anaphase II.29-30 It has long been controversial about the kinases responsible for REC8 phosphorylation. Up to now, polo, 26,31,32 casein kinase 1δ/ε (CK1)33-34 and Dbf4-dependent Cdc7 kinase (DDK) 34 are implicated in REC8 phosphorylation during meiosis in yeast and fly oocytes. Human recombinant protein of polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1), the homolog of Drosophila polo, also promotes REC8 cleavage by separase in vitro.27 Further studies are needed to clarify the exact protein kinases that are in charge for REC8 phosphorylation in vivo during meiosis in mammalian oocytes.

It is now widely appreciated that Plk1 is the ‘master regulator’ of somatic cell mitosis and involved in multiple events, including entry into mitosis, centrosome maturation, spindle assembly, the activation of spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), and the timely destruction of cohesion between sister chromatids, as well as the proper completion of cytokinesis.35 Plk1 activity is also required in regulating the gamete meiotic progression. Data from different studies confirm alterations in Plk1 activity definitely cause severe spindle defects and chromosome missegregation during mouse oocytes meiotic maturation.36-37 Though Plk1 is required unambiguously for cohesin degradation in sister chromatid splitting during somatic mitosis, whether it plays similar role during germ cell meiotic division is still not clearly revealed. It was recently reported that Plk1 promotes the phosphorylation and disassembly of synaptonemal complex, including cohesin subunit REC8, in mouse spermatocytes.38 Clear evidences are still absent about the involvement of Plk1 activity in cohesin degradation in mammalian oocytes.

The functional diversity of Plk1 in mitotic cells is associated with its consecutive posttranslational modification. Plk1 phosphorylation at Ser137 and Thr210 in vivo occurs with different timing, and regulates separate Plk1 actions.39-41 Thr210 phosphorylation is required for Plk1 activation39-40 and entry into mitosis,40-41 while phosphorylation of Ser137 takes place only in late mitosis, not required for initial activation of Plk1.39 An alteration in Ser137 phosphoryaltion can induce spindle assembly checkpoint failure and untimely premature onset of anaphase.41 However, it is still completely unknown about the pattern of Plk1 phosphorylation, as well as the subcellular distribution and potential function of phosphorylated Plk1 during meiotic division in oocytes.

In the present study we assessed the protein expression and subcellular localization of phosphorylated Plk1 in mouse oocytes during meiotic division, and examined its function by using an ATP-competitive inhibitor, BI2536. The results indicate that Plk1 phosphorylation at Ser137 (pPlk1Ser137) and Thr210 (pPlk1Thr210) occurs in oocytes, with distinct expression and localization patterns. pPlk1Ser137 localization is sensitive to BI2536, and required for meiotic spindle assembly and REC8 cleavage during oocyte meiosis.

Results

Asynchronous Plk1 phosphorylation at Ser137 and Thr210 in mouse oocytes during meiotic maturation

In somatic cells, Plk1 activity is regulated by its putative phosphorylation on Ser137 and Thr210. We investigated whether this phosphorylation occurs in mouse oocytes during meiosis. Prior to exploring the features of Plk1 phosphorylation, the protein expression pattern of total Plk1 was validated in this study. A commercial anti-Plk1 antibody (ab17057, Abcam), which recognizes the peptide sequence from residue 330 to 370, was used to detect total Plk1, no matter Ser137 or Thr210 residues are phosphorylated or not. Consistent with the previous results,36 stable and consistent quantity of Plk1 was detected during oocyte meiotic progression from germinal vesicle (GV) to metaphase II (MII) stage (Fig. 1A), manifested as a single band at 68 kDa. The expression characteristics of phosphorylated Plk1 (pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210) were directly determined using phospho-specific antibodies. As showed in Figure 1A, pPlk1Ser137 protein was detected as a single band at about 72 kDa in mouse oocytes, which was highly expressed at GV stage and sustained stable up to MII stage. pPlk1Thr210 protein was labeled as one single band more than 72 kDa at GV stage, and as 2 smaller bands after GVBD, which maintained in high and stable levels until MII stage. After being treated with lambda protein phosphatase (λ-PP), both the large band at GV and 2 small bands after GVBD were cleared away (Fig. 1B), suggesting they represent phosphorylated protein signals. The western blot results confirmed that Plk1 phosphorylation on Ser137 and Thr210 happens in oocyte meiosis in vivo. Overphosphorylation of Plk1 may occur on multi residue sites, including Ser137 and Thr210, at GV stage, and partial dephosphorylation takes place after the onset of meiotic resumption, suggesting that such modifications may function at late stages in meiotic progression.

Figure 1.

Plk1 phosphorylation on Ser137 and Thr210 occurs differently in mouse oocytes during meiosis. (A) Western blot analysis was used to detect pPlk1Ser137, pPlk1Thr210 and Plk1 protein level. For each sample, 100 oocytes were collected after 0, 2, 4, 8 and 17 h culture, corresponding to GV, GVBD, MI and MII stages, respectively. GAPDH was used as a protein loading control. Each protein was assayed at least 3 times. Plk1 was detected as one 68 kDa band in oocytes and expressed consistently stable among all stages during meiotic maturation. pPlk1Ser137 was detected as a single bind at about 72 kDa and expressed in high and stable level from GV to MII stage. pPlk1Thr210 was labeled as a single band, which was larger than 72 kDa, at GV stage, and assayed as 2 bands after GVBD, with the lower band at about 72 kDa and the upper one same as that at GV stage, both bands were sustained in stable level up to MII stage. (B) Lambda protein phosphatase (λ-PP) was used to determine the specificity of pPlk1T210 antibody. For each sample, 100 oocytes were collected and incubated in the absence (-λ-PP) or presence of λ-PP (+λ-PP) for 30 min at 30°C. The resulting sample were used for western blot analysis with pPlk1Thr210 antibody. λ-PP treatment greatly reduced the protein signals of these 2 bands.

Dynamic sub-cellular localization of Plk1 during oocyte meiosis

Though Plk1 protein was stable and consistent in quantity, its subcellular distribution was highly dynamic along oocyte meiotic progression from GV to MII stage. At GV stage, Plk1 was labeled as several round dots of different size in nucleus (Fig. S1A, a-d). These dots were gradually dismantled and reassembled as highly concentrated foci on centromeres as chromatin condensing into individual chromosomes after GVBD (Fig. S1A, e-h). This centromeric localization was consistently observed from pro-metaphase I (pro-MI) to MI, also at MII stage (Fig. S1A, i-x), and further displayed in greater detail by immunofluorecsence analysis on chromosome spread samples (Fig. S2). In addition, Plk1 was also found localized on spindle poles at MI and MII (Fig. S1B), and closely overlapped with MTOC components, pericentrin and γ-tubulin (Data not shown). Specially, Plk1 was no longer observed on polar area but distributed over the midbody structure during anaphase I (AI) / telephase I (TI) transition (Fig. S1A, q-t). These morphological data indicates Plk1 is associated with the meiotic spindle formation, spindle assembly checkpoint function and cytokenesis completion during meiotic progression in mouse oocytes.

Co-localization of pPlk1Ser137 with MTOC proteins on spindle poles

Since it was definitely ascertained by western blot results that Plk1 Ser137 and Thr210 phosphorylation happens in mouse oocyte meiosis, we then characterized the sub-cellular distribution patterns of pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210 throughout meiotic division. In order to determine the intracellular localization of pPlk1Ser137, oocytes at every typical stage of meiotic process were collected and processed for double immunofluroescent staining with pPlk1Ser137 and acetylated-tubulin. As showed in Figure 2A, in oocytes arrested at GV stage, pPlk1Ser137 was accumulated as multiple bright aggregates (foci) in germinal vesicle (Fig. 2A, a-d), and then gathered as discrete foci close to condensing chromosomes upon meiotic resumption (Fig. 2A, e-h). During pro-MI when microtubules were assembled and organized into meiotic spindle around condensed chromosomes, pPlk1Ser137 foci mass were assorted into 2 groups, migrated in the opposite directions toward the 2 poles of the forming spindle (Fig. 2A, i-l), and finally localized at the polar area of barrel-like spindle at MI stage, in an “O” or “C”-shaped configuration (Fig. 2B, c,g) with positive signals radiating outward (Fig. 2A, m-p). pPlk1Ser137 was translocated to the midzone of the spindle during AI / TI (Fig. 2A, q-t), and again focused on poles of newly formed spindle as oocytes developed to MII stage. In addition, multiple discrete foci of pPlk1Ser137 were found in the cytoplasm as oocytes underwent meiotic maturation (Fig. 2A, u-x). Signal of pPlk1Ser137 was also observed across chromosomes, especially obvious at MI and MII stages (Fig. 3A).

Figure 2.

pPlk1Ser137 subcellular distribution in mouse oocytes during meiotic division. (A) Dynamic localization of pPlk1Ser137 is associated with spindle formation during meiosis. pPlk1Ser137 was indicated in red, acetylated-tubulin in green and DNA in blue. Scale bar = 10 μm. pPlk1Ser137 was assembled as several large dots within germinal vesicle at GV stage, and reassembled as many small foci around condensing chromatin after GVBD, these foci were gradually fused and clustered into 2 groups as cell cycle progressed to pro-MI, and concentrated on 2 opposite poles of barrel-shaped spindle at MI stage. pPlk1Ser137 was transferred to the midbody during AI-TI transition and moved back to polar areas of newly formed spindle at MII stage. Cytoplasmic pPlk1Ser137 was indicated by asterisk and pPlk1Ser137 at spindle polar area was indicated by arrow and was shown in insets with 2× magnification. (B) pPlk1Ser137 was co-localized with γ-tubulin and pericentrin at MTOCs. Oocytes at MI stage were collected after an 8 h culture for double immunostaining of pPlk1Ser137 (red) either with γ-tubulin (green) (a-d) or pericentrin (green) (e-h), both of which are key components of MTOCs. DNA was visualized with DAPI in blue. Scale bar = 10 μm. At MI stage, pPlk1Ser137 concentrated in “O” or “C” shape on spindle polar area and distributed in cytoplasm and colocalized with pericentin and γ-tubulin both in cytoplasm (asterisk) and spindle poles (arrow).

Figure 3.

Unique distribution pattern of pPlk1Ser137 on chromosomes. (A) pPlk1Ser137 was accumulated persistently on centeromeres and dynamically between chromosome arms. Chromosome spreads from pro-MI, MI, and MII oocytes were processed for immunofluorescence staining with pPlk1Ser137 antibodies and CREST serum. Chromosome was labeled in blue, pPlk1Ser137 in red and CREST in green. Scale bar = 10 μm. pPlk1Ser137 was accumulated between chromosome arms from pro-MI (a-d) to MI (e-h), and only focused at local space between sister centromeres at MII stage (i-l). pPlk1Ser137 was persistently concentrated on centromeres from pro-MI to MII (i-l, arrow). (B) Quantitative analysis demonstrated that higher level of pPlk1Ser137 between chromosome arms in MI oocytes than that in pro-MI cells (P <0.01). Double asterisks (**) denote statistical differences between groups at P<0.01. (C) There was no significant difference in the level of pPlk1Ser137 at centromeres between pro-MI and MI.

pPlk1Ser137 localization on spindle poles at MI and MII stages implied its probable association with MTOCs. We then performed immunofluorescent colocalization analysis of pPlk1Ser137 with crucial components of MTOCs, pericentrin and γ-tubulin. As we expected, pPlk1Ser137 was specifically co-localized with γ-tubulin and pericentrin on the meiotic spindle poles and at cytoplasmic MTOCs at MI (Fig. 2B), as well as other typical stages of meiosis I (data not show). Specially, filamentous aggregates of pPlk1Ser137 was radiated outward from the poles and overlapped with γ-tubulin filaments. The distinct association of pPlk1Ser137 with MTOCs suggests pPlk1Ser137 may be a component of meiotic acentriolar MTOCs, thus involve in meiotic spindle assembly in oocyte meiosis.

pPlk1Ser137 persisted on centromeres and dynamicly located between chromosome arms during oocyte meiotic progression

In order to reveal the detailed characteristics of pPlk1Ser137 localization on chromosomes, we prepared chromosome spreads from oocytes developed to pro-MI, MI and MII stage, respectively, and immune-labeled with pPlk1Ser137 antibodies and auto anti-centromere serum CREST. As showed in Figure 3A, pPlk1Ser137 was persistently concentrated on centromeres from pro-MI to MI and at MII. The relative fluorescent intensity of centromeric pPlk1Ser137 was roughly equal among these stages (Fig. 3C, pro-MI vs MI, 61.82 ± 9.872 vs. 85.94 ± 6.577, P > 0.05). At the same time, pPlk1Ser137 was also dynamically clustered between chromosome arms, specifically from pro-MI and MI, pPlk1Ser137 was labeled in the full space between the arms of homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids (Fig. 3A, a-h), but only confined to the local space between centromeres of sister chromatids at MII stage (Fig. 3A, i-l). Further quantitative analysis showed that the average fluorescence intensity of pPlk1Ser137 between chromosome arms was significantly higher in MI oocytes (52.99 ± 2.363; P < 0.05) than that in pro-MI cells (15.16 ± 4.015) (Fig. 3B). Given space between chromosomes arms is where the cohesin complex accumulated, the increasing assembly of pPlk1Ser137 between chromosome arms from pro-MI to MI highly suggested its possible involvement in the resolution of cohesion along chromosome arms.

Ubiquitous distribution of pPlk1Thr210 on chromosomes during mouse oocyte meiotic division

The intracellular localization of pPlk1Thr210 was examined by double immunostaining with anti-pPlk1Thr210 and CREST anti-serum. There was no obvious pPlk1Thr210 assembly observed either in cytoplasm or in nucleus at GV stage (Fig. 4A, a–d). Upon GVBD, pPlk1Thr210 was constantly presented on chromosomes, in sharp contrast to the diverse subcellular localization of pPlk1Ser137 (Fig. 4A, e-h). From pro-MI to MI and at MII, high concentration of pPlk1Thr210 was labeled on whole chromosome scales, even on chromosomes of the first polar body (Fig. 4A, i-t). This distribution was more finely verified with immunostaining on chromosome spreads (Fig. 4B), which clearly illustrating the ubiquitous pPlk1Thr210 just like a “coat” covering the whole structure of chromosomes. During AI/TI transition, strong signal of pPlk1Thr210 was still observed on separating chromosomes, also the area of midbody (Fig. 4B, q-t). All these morphological evidences indicate that pPlk1Thr210 may be related to the establishment and maintenance of chromosome configuration during oocyte meiosis.

Figure 4.

pPlk1Thr210 subcellular localization in mouse oocytes during meiotic maturation. (A) Oocytes were collected and fixed at different stages during meiotic maturation for double immunofluorescent staining with pPlk1Thr210 antibodies and CREST anti-serum. pPlk1Thr210 was faintly labeled at GV stage, but obviously detected after GVBD and consistently distributed on chromosomes up to MII stage. (B) Chromosome spreads were prepared from pro-MI, MI, and MII oocytes and processed for immunofluorescent staining to illustrate pPlk1Thr210 localization on chromosomes in greater details. pPlk1Thr210 was ubiquitously distributed across the whole structure of chromosomes. Insets show a 2× magnified viewer of area indicated by arrows. pPlk1Thr210 was visualized in red, CREST in green and DNA in blue. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Metaphase I arrest induced by Plk1 inhibition with BI2536

The unique distributions of phosphorylated Plk1 imply the relevance of Plk1 activity in some essential cellular events controlling chromosome division during meiotic progression. We then explored the roles of Plk1 activity by using the Plk1 inhibitor BI2536. Firstly, we took an overview of the effects of BI2536 on oocyte maturation rate. GV oocytes were matured in culture medium supplemented with either 100 nM BI2536 or same volume of DMSO, and the number of oocytes developed to MI as well as MII stage was assessed by spindle morphology and chromosome alignment at 8, 10, 12, 14 and 17 h of culture. As showed in Figure 5, when checked at 8 and 10 h of culture, the majority of oocytes were matured to MI stage, there was no significant difference in the number of MI oocytes between BI2536 treatment group and control, indicating BI2536 exacted no obvious effects on the restart of meiosis and the meiotic progression to MI. With the increase in incubation time, the portion of MI oocytes continuously decreased while that of MII oocytes, characterized by the extrusion of the first polar body (1st PB), increased in control group. More specifically, the percentage of MII oocytes was 25%, 53% and 70.4% and 82%, respectively, at 10, 12, 14 and 17 h of culture (Fig. 5). However, the situation was entirely different in BI2536 group, no MII oocytes were found at all the time points in BI2536 group, oocytes were arrested at MI stage (P < 0.05). These data demonstrated that BI2536-treated oocytes could not proceed through MI stage and enter into later stages of meiotic division. As the homologous chromosome segregation is the morphological hallmarks of MI/AI transition, it can be inferred that the inactivation of Plk1 with BI2536 may inhibit the segregation of homologues and thus arrest oocytes at MI stage.

Figure 5.

Delayed MI/AI transition in BI2536-treated oocytes. The meiotic transition from MI to AI was blocked with BI2536 incubation. Oocytes were cultured either with DMSO or 100 nM BI2536 for 8, 10, 12, 14, and 17 h, and then fixed for DAPI staining to number oocytes at MI or MII stage, according to the chromosome configuration and first polar body extrusion, respectively. Oocytes were arrested at MI when checked at all the time points during BI2536 incubation (P <0.01).

Defects in meiotic spindle, MTOC proteins localization and chromosome alignment in oocytes with disassociated pPlk1Ser137 by BI2536

Next, we explored the possible mechanism for MI arrest induced by BI2536. Firstly, we analyzed the effects of drug treatment on the protein expression and subcellular distribution of pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210 in mouse oocytes. GV oocytes were cultured for 8 h in the absence or presence of BI2536, and then collected for analysis with western blot or immunofluorescence. Compared with the control oocytes, we did not find significant alteration in protein expression of both pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210 in BI2536-treated oocytes, indicating BI2536 had no effects on Plk1 phosphorylation on Ser137 and Thr210 (Fig. 6A). In other words, it did not impact the activation of Plk1. Surprisingly, when analyzed using immunofluorescence, pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210 responded to BI2536 differently in subcellular distribution. In BI2536-treated oocytes, pPlk1Thr210 was markedly labeled on chromosomes with no obvious difference in the fluorescent intensity compared with that in control cells (Figs. S3A). For more detailed display, these oocytes were processed for chromosome spreading and immune-labeling with CREST and pPlk1Thr210 antibodies, and the results showed that all the individual chromosomes were thoroughly covered with a layer of pPlk1Thr210 in both BI2536-treated oocytes and control cells (Figs. S3B). In sharp contrast to pPlk1Thr210, pPlk1Ser137 subcellular localization was heavily damaged (Fig. 6B and D), especially on the spindle poles, causing abnormality in meiotic spindle structures. So it is safe to say that the small molecule inhibitor BI2536 does not influence Plk1 activation, namely its phosphorylation on Ser137 and Thr210, but blocks the sub-cellular positioning of phosphorylated Plk1, especially that of pPlk1Ser137.

Figure 6.

BI2536-induced pPlk1Ser137 dislocalization suppressed γ-tubulin recruitment to MTOCs, disturbed meiotic spindle formation. (A) Western blot analysis indicated BI2536 effects on protein expression of pPlk1Thr210 and pPlk1Ser137. GAPDH was used as the loading control. The results presented 3 replicates of experiments. Statistical analysis demonstrated the protein levels of pPlk1Thr210 and pPlk1Ser137 were not changed when checked at all time points. (B) Disturbed subcellular localization of pPlk1Ser137 lead to abnormal meiotic spindle structure in BI2536-treated oocytes (e-h). (C) γ-tubulin recruitment to MTOCs was disrupted in oocytes with dislocalized pPlk1Ser137 after BI2536 treatment (e-h). (D) Statistical analysis indicates the percentage of oocytes with weak or no pPlk1Ser137 was significantly higher in BI2536 treatment group. The number of oocytes with disrupted γ-tubulin at MTOCs or abnormal spindle configuration was also higher in BI2536 group. Single asterisk (*) and double asterisks (**) denote statistical differences between groups at P <0.05 and 0.01, respectively. DNA was showed in blue, pPlk1Ser137 in red, and acetylated-tubulin or γ-tubulin in green. Insets show a 2× magnification of the spindle pole area where arrows indicated. Misaligned chromosomes denoted by arrowheads. Scale bar = 10 μm.

In order to fully clarify BI2536 effects on pPlk1Ser137 localization and spindle structure, oocytes were collected and processed for double immunofluorescent staining of pPlk1Ser137 and acetylated-tubulin after drug incubation as mentioned above. Intuitively, in DMSO group the vast majority of MI oocytes were characterized by highly concentrated foci of pPlk1Ser137 on 2 opposite poles of properly organized barrel-shaped spindles (more than 80%) (Fig. 6B, a-d and D), with correctly aligned chromosomes at spindle equator. However, in BI2536 group, pPlk1Ser137 distribution was severely destroyed, there was no or only very weak pPlk1Ser137 observed in polar area of spindles with various morphological defects (Fig. 6B, e-h and D), mainly manifested as asymmetrical spindles with none-uniform microtubule density, mono-polar spindles and bipolar spindles with broadened poles or long axis. Perhaps ascribed to the lack of driving force from functional spindle apparatus, chromosomes were not properly aligned in a neat line, but huddled together or scattered irregularly in the cytoplasm with one or several chromosomes away from the spindle.

Since pPlk1Ser137 is precisely co-localized with MTOC components γ-tubulin and pericentrin, which are essential for spindle formation, it is tempted to speculate that mislocalized pPlk1Ser137 might potentially undermine the polar positioning of MTOC proteins, thus leading to dysfunctional MTOC, a direct cause accounting for defective spindle formed in BI2536-treated oocytes. We therefore evaluated the sub-cellular localization of γ-tubulin and pericentrin in oocytes after BI2536 incubation. As showed in Figure 6C, in most control oocytes (more than 80%), bright foci of both γ-tubulin and pPlk1Ser137 were pronouncedly labeled and tightly co-localized on the poles of correctly formed bi-polar spindle, as well as at the cytoplasmic MTOCs. On the contrary, in BI2536 group, the fluorescent signal of γ-tubulin and pPlk1Ser137 were simultaneously reduced, only detectable at polar MTOCs in less than 50% oocytes. Similar to γ-tubulin, pericentrin accumulation at MTOCs was also destroyed in BI2536-treated oocytes (Figs. S4A and B). These data indicate that BI2536-induced pPlk1Ser137 disassociation from spindle poles impaired the localization of γ-tubulin and pericentrin, disrupted the formation of MTOC with full function, and consequently resulted in spindle assembly defects.

Sustained spindle assembly checkpoint activity in oocytes treated with BI2536

The abnormal spindle configuration and the significant chromosome misalignment observed in BI2536-treated oocytes points to a lack of stable kinetochore-microtubule connection, which prompting us to determine whether this status is recognized by spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC). The localization of MAD1, a crucial SAC protein required for SAC full activation, was assessed in MI oocytes after drug incubation. MAD1 signal was obviously detected at kinetochores in almost half of the BI2536-treated oocytes (48.62 ± 5.44%), which was significantly higher than that in control oocytes (9.62 ± 5.69%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 7A and B). Detection of MAD1 at kinetochores indicates the activation of SAC system, which functions to delay the meiotic transition from MI to AI, logically consistent with the fact that the majority of oocytes were arrested at MI in BI2536-treated group.

Figure 7.

Active function of spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) in oocytes treated with BI2536. (A) Chromosome spreads were prepared and immune-labeled with antibodies to MAD1 after an 8 h culture with the presence of DMSO or BI2536. Representative images showed that MAD2 was faintly labeled at centromere-kinetochore area in control oocytes (A: a-d), but obviously detected in BI2536-treated oocytes (A: e-h). (B) Statistical analysis showed that the number of oocytes with positive MAD1 was significantly higher in BI2536 group, indicates the presence of functional SAC in BI2536-treated oocytes (P <0.01). DNA was labeled in blue, MAD1 in red and CREST in green. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Delayed REC8 degradation in oocytes with reduced pPlk1Ser137 between chromosome arms in BI2536-treated oocytes

Immunofluorescent labeling on chromosome spreads showed that pPlk1Ser137 along chromosome arms almost disappeared in BI2536-treated oocytes (Fig. 8A). Statistical analysis confirmed that the number of oocytes with weak or no pPlk1Ser137 between chromosome arms was significantly higher in BI2536 group than that in control group (92.8 ± 2.75 % vs. 4.6 ± 0.38%; P < 0.01). However, pPlk1Ser137 localization on centromeres was not affected with BI2536. Together with the fact showed above, that the protein amount of pPlk1Ser137 was not changed by BI2536 (Fig. 6A), this data indicates BI2536 employment blocked pPlk1Ser137 recruitment in the space between chromosome arms, with no effects on the level of protein expression.

Figure 8.

Loss of pPlk1Ser137 between chromosome arms was associated with delayed REC8 cleavage after BI2536 treatment. (A) Representative images demonstrated pPlk1Ser137 accumulation was reduced between chromosome arms but remained stable on centromeres in oocytes incubated in 100 nM BI2536 for 8 h (e-h). DNA was labeled in blue, pPlk1Ser137 in red and CREST in green. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Statistical analysis indicated the percentage of oocytes with reduced pPlk1Ser137 between chromosome arms was significantly higher in BI2536 group than that in DMSO group (P < 0.0001). (C) Western blot analysis showed REC8 expression was reduced after BI2536 treatment. GAPDH was applied as the loading control. The results represented 3 replicates of experiments. Statistical analysis indicated the protein level of REC8 was significantly decreased when checked at 13 h and 17 h of BI2536 incubation (P < 0.01).

During oocyte meiotic division, cohesion cleavage between chromosome arms is a decisive step for chromosome segregation, and REC8 phosphorylation is the critical prerequisite for its degredation.26-28 We further examined whether reduced pPlk1Ser137 blocked REC8 cleavage from chromosome axes, an alternate logical explain for oocyte arrest at MI. As showed in Figure 8C, as oocytes were cultured for up to 8, 10, 13 and 17 h, the protein amount of REC8 gradually decreased in DMSO group, while it remained stable in BI2536 group, suggesting pPlk1Ser137 dissociation from chromosomes might prevent REC8 cleavage, thus delay chromosomes segregation and the meiotic transition from MI to AI.

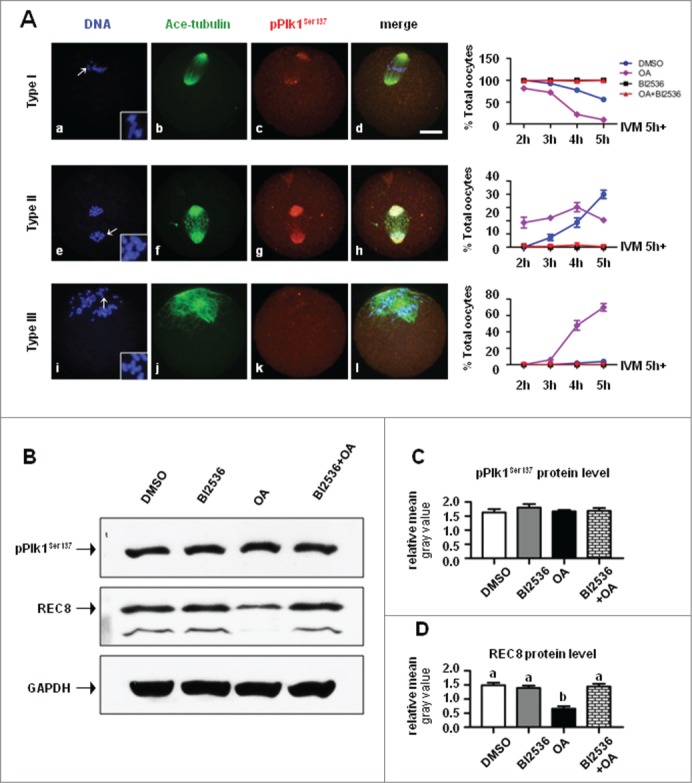

To further confirm the possible role of pPlk1Ser137 in REC8 cleavage, oocytes were normally cultured for 5 h, by which time most oocytes are supposed to progress to pro-MI. Then, these oocytes were transferred to medium containing DMSO, 100 nM BI2536, 200 nM okadaic acid (OA), and 100 nM BI2536 + 200 nM OA, respectively, and incubated for additional 2, 3, 4 and 5 h. The number of oocytes with segregated homologues and sister chromatids (Fig. 9A) was significantly higher in OA group than in other groups when checked at any time points examined, while no oocytes with either segregated homologues or chromatids were observed in BI2536 group. Importantly, OA-induced precocious separation of homolog or sister chromatids was reversed by combined application of BI2536. In logical consistence, western blot results demonstrated the protein level of REC8 was significantly lower in OA-treated group than in other groups after 3 h of drug incubation (Fig. 9B, C and D). All together, these results indicated that pPlk1Ser137 may directly phosphorylate REC8 and promote its cleavage.

Figure 9.

BI2536 reversed OA-induced REC8 cleavage and precocious chromosome segregation. (A) Oocytes matured in vitro for 5 h were further cultured with DMSO, 200 nM OA, 100 nM BI2536 or with 200 nM OA and 100 nM BI2536 for additional 2,3,4, and 5 h, and fixed for immunofluorescent staining of ace-tubulin (green) to visualize the structure of spindle and chromosomes (blue). Configuration of chromosomes was shown in insets with a 2× magnification of arrows indicated area. Type I: oocytes with non-segregated homologs, Type II: oocytes with segregated homologus Type III: oocytes with segregated sister chromatids. Percentage of Type I, II and III oocytes in 4 treatment groups: DMSO (blue line, circle), OA (violet line, square), BI2536 (red line, triangle), and OA + BI2536 (green, inverted triangle). (B) BI2536 reversed OA-induced REC8 cleavage. Protein levels of pPlk1Ser137 and REC8 were assessed by western blot after pro-MI oocytes (IVM 5h) were treated for 3 h with DMSO, 200 nM OA, 100 nM BI2536 and 200 nM OA + 100 nM BI2536. 100 oocytes were included in each sample. (C) Statistical analysis showed there was no difference in pPlk1Ser137 level among the 4 groups. (D) Statistical data demonstrated the protein level of REC8 was reduced in oocytes treated with OA, and significantly lower than that in groups of DMSO, BI2536 and BI2536 + OA (P < 0.01), suggesting OA-induced REC8 degradation could be reversed by combined application of BI2536.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that Plk1 is phosphorylated at Ser137 and Thr210 during meiotic division in mouse oocytes, and required for meiotic spindle formation and cohesin REC8 cleavage, with pPlk1Ser137 is the major executive molecule.

Previous studies in somatic cells display Plk1 is activated when it is phosphorylated at Thr210 and Ser137. Thr210 phosphorylation occurs before entry into mitosis and precedes Ser137 phosphorylation, which happens in late stage of mitosis.39 In the present study, we for the first time established the phosphorylation pattern of Ser137 and Thr210 in mouse oocytes during meiotic maturation. Obviously, Ser137 phosphorylation occurs before the resumption of meiosis. High level of pPlk1Ser137 protein expression was detected at GV stage and remained stable up to MII, which is different from that reported in mitosis during which Ser137 is phosphorylated just before anaphase. This inconsistency suggests, unlike its limited working time during mitosis, Ser137 phosphorylation has a meiotic specific role in regulating Plk1 action, and may perform functions in many meiotic respects. Thr210 phosphorylation is complicated, pPlk1Thr210 was labeled as a single band at GV stage, it is further converted into 2 bands after GVBD, implying Plk1 is phosphorylated at multiple amino residue sites, more than just Thr210 in GV oocytes[50] while in oocytes resumed meiosis, the over-phosphorylated Plk1 is partially dephosphorylated, thus giving rise to the production of Plk1 with single phosphorylation at Thr210 (pPlk1Thr210). The status conversation of Thr210 phosphorylation is consistent with the phosphorylation timing of some crucial proteins upon the resumption of meiosis, such as histone H3,42-43 lim kinase 1 (LIMK1) (unpublished data), protein kinase C (PKC) 18-19 and amp-activated kinase (AMPK),44 etc., which are important for chromosome condensation and spindle assembly, as well as cytokinesis initiation and completion during oocyte meiosis. The emerge of 2 phosphorylated peptides recongnized by pPlk1Thr210 antibody might mark the full activation of Plk1, which may be involved in the restart and timely progression of meiosis in mouse oocytes.

Ser137 phosphorylation may partially activate Plk1 and induce Plk1 conformation change, and then facilitating Thr210 phosphorylation and the complete activation of Plk1.45 Ser137 and Thr210 were phosphorylated in different pathway or by different upstream kinases. Bora and Aurora A act synergistically to initiate Thr210 phosphorylation in G2 phase,41,46 and sustain this modification in mitosis.47 Some other kinases are also reported as upstream regulators of Plk1, including members of a subfamily of Ste20-related enzymes, Xenopus polo-like kinase kinase 1 (xPlkk1), STE20-like kinase (SLK), lymphocyte-oriented kinase (LOK), cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and protein kinase A (PKA).40,48-50 So far no upstream kinase responsible for phosphorylating Ser137 has been identified. It is proposed that Ser137 may be an autophosphorylation site, undergoing kinase-independent phosphorylation pattern.40

Essentially like Plk1, pPlk1Ser137 is co-localized with MTOC core proteins, pericentrin and γ-tubulin, on spindle poles. Filaments of pPlk1Ser137 were also observed on the spindle microtubules, just like that of γ-tubulin. This data suggests pPlk1Ser137 is a MTOC-associated protein in oocytes. Both Plk1 and pPlk1Ser137 are persistently localized on centromeres from pro-MI to MI and at MII stage, implying Plk1 activity may be involved in attachment of spindle microtubules to kinetochores of chromosomes. More important, the pPlk1Ser137 aggregation between chromosome arms is highly dynamic during meiotic progression, and resembles REC8 localization in meiotic oocytes,51 indicates pPlk1Ser137 may be involved in the regulation of REC8 cleavage. pPlk1Thr210 is organized as a “coat” wrapping the chromosomes after GVBD, and remains associated with chromosomes up to MII. This distribution is in sharp contrast to previous reports that pPlk1Thr210 was localized to centrosomes on spindle poles in mitotic cells,37 suggesting Thr210 phosphorylation exerts different functional emphasis between mitosis and meiosis. Different subcellular distributions of pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210 in oocytes signal suggest their distinct effects on some meiotic aspects. In somatic cells, expression of constitutive active Plk1S137D induces untimely anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) activation and APC/C substrate cyclin B1 degradation, consequently causing cell past an active spindle assembly checkpoint. In contrast, expression of Plk1T210D mutation delays the mitotic progression due to a spindle assembly checkpoint-dependent arrest.39 It is also reported that Plk1S137D could promote cell to enter mitosis even earlier than Plk1T210D does.39 These data suggest Ser137 and Thr210 play different, and in some cases, antagonistic functions in somatic cells during mitosis. Given the timing and expression pattern of Ser137 and Thr210 phosphorylation in oocyte meiosis is different from that in somatic cell mitosis, it is much necessary to clarify their specific meiotic functions in oocytes using similar molecular mutation techniques.

BI2536 is a highly selective inhibitor to Plk1, it shows 4- and 11-fold greater selectivity against Plk2 and Plk3.52 In a variety types of somatic cells, BI2536 treatment blocks γ-tubulin recruitment at mitotic centrosomes and cohesin release from chromosome arms, inducing abnormal spindle formation and delayed chromosome separation.52-53 In the present study, BI2536 administration does not affect Plk1 phosphorylation at Ser137 and Thr210, as well as the protein expression of phosphorylated Plk1. The inhibitor does not prevent pPlk1Thr210 recruitment on chromosomes, but severely disrupts pPlk1Ser137 accumulation at MTOCs and between chromosome arms, with the exception of its concentration on centromeres. These data suggest BI2536 exerts no influence on Plk1 activation but selectively affects the subcellular localization of pPlk1Ser137. The polo-box domain (PBD) in the C-terminal region of Plk1 is critical for targeting Plk1 to specific subcellular structures by serving as a phosphopeptide-binding module, whose optimal sequence motif is Ser-(pThr/pSer)-(Pro/X).54 Priming phosphorylation of a PBD-binding target is a critical step to promote the PBD-dependent interaction. Studies have demonstrated that the phosphorylated motif for PBD binding could be generated by the activity either of a Pro-directed kinase (non-self-priming mechanism) or of Plk1 itself.54 We speculate that the different response of pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210 to BI2536 may be attributed to their respective subcellular positioning under the guide of distinct mechanisms. Possibly, the ability of pPlk1Ser137 binding to MTOC or chromosomes, may be facilitated by its substrate proteins phosphorylation dependent on “self-priming mechanism,” which can be blocked when Plk1 activity is inhibited with BI2536, impairing the binding site formation. On other hand, pPlk1Thr210 targeting to chromosomes and pPlk1Ser137 recruiting to centromeres are dependent on “non-self-priming mechanism,” which cannot be affected when Plk1 activity is inhibited by BI2536.

BI2536-induced pPlk1Ser137 delocalization results in abnormal spindle formation, which is fundamentally associated with defects in MTOC structure and function, manifested by disrupted recruitment of MTOC core components, γ-tubulin and pericentrin, on spindle poles. In somatic cell, γ-tubulin catalyzes microtubule assembly while pericentrin scaffolds MTOC platform formation for γ-tubulin anchoring.3-7 We previously confirmed that the deletion of pericentrin destroys the subcellular localization of γ-tubulin, causing abnormal microtubule organization in mouse oocytes.15 Loss of NEDD1 (neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated gene 1), a γ-tubulin adaptor, blocks γ-tubulin anchoring at MTOC, and disturbs the bipolar spindle formation in oocyte meiosis.55 A growing body of evidences suggest that Plk1 promotes the recruitment of γ-tubulin to the centrosome or MTOCs in dividing cells,56 which involves multiple PCM proteins and therefore potential Plk1 substrates.35,57 Plk1 phosphorylation of pericentrin at the onset of mitosis is required for the recruitment of centrosomal proteins, such as NEDD1, γ-tubulin, Aurora A, and Plk1 itelf, into the centrosome during mitosis.58 NEDD1 is also phosphorylated by Plk1, facilitating its interaction with γ-tubulin for targeting the γTuRC to the centrosome.59,60 In the present study, we show that pPlk1Ser137 is co-localized with pericentrin and γ-tubulin on MTOCs, and particularly, pPlk1Ser137 filamentous aggregates are labeled on spindle microtubules, resembling the distribution of γ-tubulin and NEDD1 55 in oocytes, implying pPlk1Ser137 may be the practical executor of Plk1 action in regulating MTOC formation in mouse oocytes, this speculation is supported by the fact that BI2536-induced disassociation of pPlk1Ser137 disturbs the formation of functional MTOCs and in turn the organizing of meiotic spindle in oocytes.

We demonstrate for the first time that pPlk1Ser137 dynamically aggregates between chromosome arms in mouse oocytes during meiotic maturation, with assembly along the length of chromosome axis up to MI stage and limited accumulation in the local space between sister centromeres at MII. This localization pattern is similar with that of cohesin proteins, including REC8, suggesting its potential involvement in cohesin cleavage during meiotic division. This hypothesis is confirmed by a functional analysis using BI2536. In response to BI2536 treatment, pPlk1Ser137 is disassociated from chromosome arms, concomitantly, REC8 cleavage is suppressed, indicating properly localized pPlk1Ser137 is involved in cohesin degradation, perhaps phosphorylates REC8, enabling it to be degradable.26-28 It is well known that PP2A prevent REC8 phosphorylation and thus protects it from cleavage by separase.29-30 Okadaic acid (OA), an inhibitor to PP2A, can antagonize the protect effect of PP2A on REC8 and promote its destruction, inducing precocious separation of paired chromosomes. We observed that OA treatment leads to precocious separation of homologous chromosomes and sister chromatids in mouse oocytes, while BI2536 can reverse OA effect, preventing REC8 degradation and chromosome segregation induced by OA. These results prompt us to propose that Plk1 activity is involved in REC8 phosphorylation, facilitating its destruction in mammalian oocyte meiosis. It has been confirmed that casein kinase 1δ/ε (CK1δ/ε) and/or Dbf4-dependent Cdc7 kinase (DDK) is responsible for REC8 phosphorylation in yeast oocytes during meiotic division.33-34 It is still not identified which kinase is required for REC8 phosphorylation in mammalian oocytes. Our data for the first time confirm the participation of Plk1 activity in REC8 cleavage in mouse oocytes. Interestingly, it is pPlk1Ser137 but not Plk1 that is dynamically assembled between chromosome arms, so we propose that pPlk1Ser137 is the action executor of Plk1 activity for REC8 destruction.

We noticed that pPlk1Ser137 localization on centromeres was persisted after Plk1 inhibition with BI2536, suggesting pPlk1Ser137 recruitment to centromeres depends on non-self-priming binding mechanism. The sustained pPlk1Ser137 is colocalized with MAD1, the core component of spindle assembly checkpoint, on centromeres, which means persistent activation of SAC. In other words, the activation of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) is effectively inhibited, partially explaining the meiotic arrest at MI stage of BI2536-treated oocytes. The effect of Plk1 on APC/C activity reported here is consistent with those reported in somatic cell39 and mouse oocyte.37 Therefore, it is reasonable to say that centromeric pPlk1Ser137 is involvement in functional setup of SAC in oocytes during meiosis.

In conclusion, our current study demonstrates that Plk1 activity is required for meiotic spindle assembly and REC8 cleavage in mouse oocytes during meiotic division. Moreover, phosphorylated Plk1, pPlk1Ser137 and pPlk1Thr210, exhibits distinct expression and subcellular distribution pattern in oocyte meiosis, with pPlk1Ser137 is the action executor of Plk1 activity in regulating MTOC formation and cohesin subunit REC8 cleavage. Further molecular studies are still needed to clarify the specific function and molecular mechanisms of Ser137 and Thr210 phosphorylation in mammalian oocytes during meiotic maturation.

Materials and Methods

Cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) collection and in vitro maturation (IVM)

Pre-pubertal (day 21–23 of age) BALB/C × C57BL/6 first filial generation (F1) (CB6F1) female mice were treated with intraperitoneal administration of 10 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG, HOR272, Beijing XinHuiZeAo Science and Technology). At 44–48 h post PMSG injection, ovaries were dissected from mice and placed in Hepes-buffered Minimum Essential Medium (HEPES-MEM) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10099–141, Gibco), cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were collected by puncturing the large antral follicles with a 25-gauge syringe needle. COCs were cultured in MEM containing 3 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA, A1933, Sigma) and 10% FBS in a humidified chamber at 37 °C with an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Oocytes at prophase I, usually known as germinal vesical (GV) stage, germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), pro-metaphase I (pro-MI), metaphase I (MI) and metaphase-II (MII) stages were collected after cultures of 0 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h and 17 h, respectively. MII oocytes were also collected from the oviducts of super-ovulated females approximately 14 h after treatment with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, Beijing XinHuiZeAo Science and Technology). Thereafter, oocytes were dissociated from surrounding cumulus cells by gentle pipetting, denuded oocytes were pooled together for subsequently experimentations.

All procedures were approved and performed in accordance with guidelines of Animal Care and Use Committee of Capital Medical University.

Immunofluorescence

Denuded oocytes were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA, P158127, Sigma) in PEM Buffer (100 mM Pipes, pH 6.9, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h, then washed 3 times for 20 min in PBS containing 0.2% Tween-20 (PBST), and blocked in PBST containing 1% BSA, 0.3 M glycine and 10% FBS for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-phospho-Plk1 (Ser137) (pPlk1Ser137) (1:1000, #07–1348, Millipore), mouse anti-phospho-Plk1 (Thr210) (pPlk1Thr210) (1:3000, ab39068, Abcam), mouse anti-Plk1 (1:300, ab17057, Abcam), mouse anti-acetylated tubulin (1:10000, T7451, Sigma), mouse anti-γ-tubulin (1:1000, T6557, Sigma), mouse anti-pericentrin (1:3000, 611814, BD Biosciences), mouse anti-MAD1 (1:100, SC-137025, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and human anti-centromere serum (CREST, 1:1000, 90C-CS1058, Fitzgerald). Subclass-specific secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 555 (A21202 and A21430, Invitrogen) at 1:1000 dilutions were used to detect primary antibodies. After antibody incubations, cells were washed 3 times with PBST for 20 min each, and then mounted on slides in VECTASHIELD mounting medium containing DAPI (H-1200, Vector Laboratories). Fluorescent images were obtained with an upright fluorescent microscope and imaging software (Olympus Microsystems).

For immunofluorescence analysis of chromosome spreads, oocytes at pro-MI, MI and MII stages were collected with the same method described above and processed for chromosome spreading according to a previous report with some modifications.55 Briefly, oocytes were exposed to acid Tyrode's solution (T1788, Sigma) for 2 min at 37 °C to remove the surrounding zona pellucida. After a brief recovery in HEPES-MEM, a total of 10 oocytes each time were carefully transferred into a 20 μl drop of hypotonic fixative (1% paraformaldehyde in distilled H2O containing 0.1% Triton X-100) on clean microscope slides with a finely drawn pipette, the oocytes burst within seconds of exposure to this solution and slowly ‘melted’ onto the slides. The slides were air-dried thoroughly at room temperature before being processed for fluorescent immunostaining. After washed 3 times in PBST prior to 45-min incubation with blocking solution at room temperature, chromosomes on slides were then immunolabeled at 4 °C overnight with CREST serum (1:100), anti-Plk1 (1:500), anti-pPlk1Ser137 (1:500), anti-pPlk1Thr210 (1:500) or anti-MAD1 antibody (1:500). Slides were washed 3 times in PBST, and then followed by 45-min incubation at room temperature with Alexa 488-conjugated and Alexa 555-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500) against the appropriate species. After washed with PBST, spread chromosomes were counter-stained in mounting medium with DAPI. Fluorescence images were captured with a fluorescence microscope. Those images appeared well spread chromosomes and showed optimal specific staining were selected for densitometric analysis of the target proteins using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC). A total of 10–15 optimal images from either pro-MI or MI group were analyzed each time, and this experiment was repeated with 3 sets of cells cultured in separate, independent experiments.

Western blot

A total of 100 oocytes were collected and frozen in Laemmli buffer (#161–0737, BIO-RAD) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (P2714, Sigma). Protein samples were boiled for 5 min before being separated on 10% acrylamide gels containing 0.1% SDS and electrically transferred onto hydrophobic polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF, IPVH00010, Millipore). Nonspecific binding of primary antibodies were blocked by immersing membrane in 5% non-fat dried milk dissolved in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Anti-Plk1 (1:200), anti-pPlk1Ser137 (1:8000), anti-pPlk1Thr210 (1:1000) and anti-REC8 antibody (1:500, Abcam) were used to detect protein expression. After overnight incubation with these primary antibodies at 4 °C, the membranes were washed 3 times with TBST, each for 20 min, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (LP1002a and LP1001a, ABGENT) at 1:4000–6000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Thereafter the membranes were washed 3 times in TBST, reacted with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (P1010, Applygen Technologies Inc.) for peroxidase activity for 1 min at room temperature and exposed to X-ray film to visualize the specific protein bands. As a loading control, the blots were stripped and detected with a rabbit monoclonal anti-GAPDH (1:2000, G9545, Sigma) antibody. The immunoreactive bands were quantified by densitometric analysis using the gel analysis submenu of Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC), and normalized to GAPDH.

Lambda protein phosphatase treatment

Samples containing 100 MI oocytes in Laemmli buffer were mixed with kinase reaction buffer and MnCl suplemented with or without 0.5ul lambda protein phosphatase (λ-PP, NEB #P0753, 400,000 units/ml). After a 30-min incubation at 30°C, samples were boiled for 5 min at 100°C and then processed for western blot analysis with pPlk1Thr210 antibody.

Chemical reagent treatments

Oocytes were treated with BI2536 (SYN1019, SYNkinase), a specific inhibitor to Plk1, and okadaic acid (OA, CAS 459616, Millipore), the phosphatase inhibitor. Stocks were made in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, A3672, Applichem GmbH), and the final concentration was 100 nM for BI2536 and 200 nM for OA in maturation medium. Control oocytes were treated with the same concentration of DMSO in the medium before examination. To determine the role of Plk1 activity during oocyte meiotic maturation, GV oocytes were incubated in maturation medium containing 100 nM BI2536 for 8 h, 10 h, 13 h and 17 h. For the evaluation of Plk1 function in meiotic transition from MI to anaphase I (AI), GV oocytes were initially cultured in normal maturation medium for 5 h, putatively developed to pro-MI stage, then incubated for additional 2 h, 3 h, 4 h and 5 h in the same medium with the presence of, respectively, DMSO, 100 nM BI2536, 200 nM OA, or 100 nM BI2536 + 200 nM OA. After treatment, oocytes were washed thoroughly and processed for either immunofluorescence or western blot assessment.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as Mean ± SEM of a minimum of 3 independent experimental replicates. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Difference in protein expression among groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and post hoc comparisons were performed. Difference in immunofluorescence intensity between groups was analyzed by Student's t-test. All percentages were subjected to arcsine transformation prior to be analyzed by ANOVA or Student's t-test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants to W.M. from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471108 and 31271253), Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (20121107120019), Scientific Research Common Program of Beijing Municipal Commission of Education (KM201310025005) and Natural Science Foundation of Beijing, China (7132030).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Xin Li and Haojie Wei for their critical technical assistance during this study.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1.Andersen SS. Molecular characteristics of the centrosome. Int Rev Cytol 1999; 187:51-109; PMID:10212978; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62416-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornens M. Centrosome composition and microtubule anchoring mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2002; 14:25-34; PMID:11792541; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0955-0674(01)00290-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moritz M, Braunfeld MB, Guénebaut V, Heuser J, Agard DA. Structure of the gamma-tubulin ring complex: a template for microtubule nucleation. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2:365-70; PMID:10854328; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35014058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiese C, Zheng Y. A new function for the gamma-tubulin ring complex as a microtubule minus-end cap. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2:358-64; PMID:10854327; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35014051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerman WC, Sillibourne J, Rosa J, Doxsey SJ. Mitosis-specific anchoring of gamma tubulin complexes by pericentrin controls spindle organization and mitotic entry. Mol Biol Cell 2004; 15:3642-57; PMID:15146056; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S, Rhee K. Importance of the CEP215-pericentrin interaction for centrosome maturation during mitosis. PLoS One 2014; 9(1): e87016; PMID:24466316; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0087016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez-Ferreria MA, Rath U, Buster DW, Chanda SK, Caldwell JS, Rines DR, Sharp DJ. Human Cep192 is required for mitotic centrosome and spindle assembly. Curr Biol 2007; 17:1960-66; PMID:17980596; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szollosi D, Calarco P, Donahue RP. Absence of centrioles in the first and second meiotic spindles of mouse oocytes. J Cell Sci 1972; 11:521-41; PMID:5076360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumont J, Desai A. Acentrosomal spindle assembly and chromosome segregation during oocyte meiosis. Trends Cell Biol 2012; 22:241-49; PMID:22480579; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gueth-Hallonet C, Antony C, Aghion J, Santa-Maria A, Lajoie-Mazenc I, Wright M, Maro B. gamma-Tubulin is present in acentriolar MTOCs during early mouse development. J Cell Sci 1993; 105:157-66; PMID:8360270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doxsey SJ, Stein P, Evans L, Calarco PD, Kirschner M. Pericentrin, highly conserved centrosome protein involved in microtubule organization. Cell 1994; 76:639-50; PMID:8124707; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90504-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carabatsos MJ, Combelles CM, Messinger SM, Albertini DF. Sorting and reorganization of centrosomes during oocyte maturation in the mouse. Microsc Res Tech 2000; 49:435-44; PMID:10842370; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000601)49:5%3c435::AID-JEMT5%3e3.0.CO;2-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Combelles CM, Albertini DF. Microtubule patterning during meiotic maturation in mouse oocytes is determined by cell cycle-specific sorting and redistribution of gamma-tubulin. Dev Biol 2001; 239:281-94; PMID:11784035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/dbio.2001.0444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuh M, Ellenberg J. Self-organization of MTOCs replaces centrosome function during acentrosomal spindle assembly in live mouse oocytes. Cell 2007; 130:484-98; PMID:17693257; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma W, Viveiros MM. Depletion of pericentrin in mouse oocytes disrupts microtubule organizing center function and meiotic spindle organization. Mol Reprod Dev 2014; 81:1019-29; PMID:25266793; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/mrd.22422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saskova A, Solc P, Baran V, Kubelka M, Schultz RM, Motlik J. Aurora kinase A controls meiosis I progression in mouse oocytes. Cell Cycle 2008; 7:2368-76; PMID:18677115; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.6361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunet S, Dumont J, Lee KW, Kinoshita K, Hikal P, Gruss OJ, Maro B, Verlhac MH. Meiotic regulation of TPX2 protein levels governs cell cycle progression in mouse oocytes. PLoS One 2008; 3:e3338; PMID:18833336; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0003338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma W, Koch JA, Viveiros MM. Protein kinase C delta (PKCd) interacts with microtubule organizing center (MTOC)-associated proteins and participates in meiotic spindle organization. Dev Biol 2008; 320:414-25; PMID:18602096; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baluch DP, Capco DG. GSK3b mediates acentromeric spindle stabilization by activated PKCz. Dev Bio. 2008; 317:46-58; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi T, Koshimizu U, Abe H, Obinata T, Nakamura T. Functional involvement of Xenopus LIM kinases in progression of oocyte maturation. Dev Biol 2001; 229:554-67; PMID:11150247; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/dbio.2000.9999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin S, Sun XF, Schatten H, Sun QY. Molecular insights into mechanisms regulating faithful chromosome separation in female meiosis. Cell Cycle 2008; 7:2997-3005; PMID:18802407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.7.19.6809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, Kitajima TS, Tanno Y, Yoshida K, Morita T, Miyano T, et al.. Unified mode of centromeric protection by shugoshin in mammalian oocytes and somatic cells. Nat Cell Biol 2008; 10:42-52; PMID:18084284; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasmyth K. Cohesin: a catenase with separate entry and exit gates? Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13:1170-77; PMID:21968990; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buonomo SB, Clyne RK, Fuchs J, Loidl J, Uhlmann F, Nasmyth K. Disjunction of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I depends on proteolytic cleavage of the meiotic cohesin Rec8 by separin. Cell 2000; 103:387-98; PMID:11081626; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00131-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitajima TS, Miyazaki Y, Yamamoto M, Watanabe Y. Rec8 cleavage by separase is required for meiotic nuclear divisions in fission yeast. EMBO J 2003; 22:5643-53; PMID:14532136; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/cdg527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brar GA, Kiburz BM, Zhang Y, Kim JE, White F, Amon A. Rec8 phosphorylation and recombination promote the step-wise loss of cohesins in meiosis. Nature 2006; 441:532-36; PMID:16672979; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature04794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kudo NR, Anger M, Peters AH, Stemmann O, Theussl HC, Helmhart W, Kudo H, Heyting C, Nasmyth K. Role of cleavage by separase of the Rec8 kleisin subunit of cohesin during mammalian meiosis I. J Cell Sci 2009; 122:2686-98; PMID:19625504; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.035287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rumpf C, Cipak L, Dudas A, Benko Z, Pozgajova M, Riedel CG, Ammerer G, Mechtler K, Gregan J. Casein kinase 1 is required for efficient removal of Rec8 during meiosis I. Cell Cycle 2010; 9:2657-62; PMID:20581463; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.9.13.12146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitajima TS, Sakuno T, Ishiguro K, Iemura S, Natsume T, Kawashima SA, Watanabe Y. Shugoshin collaborates with protein phosphatase 2A to protect cohesin. Nature 2006; 441(7089):46-52; PMID:16541025; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature04663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riedel CG, Katis VL, Katou Y, Mori S, Itoh T, Helmhart W, Gálová M, Petronczki M, Gregan J, Cetin B, Mudrak I, Ogris E, Mechtler K, Pelletier L, Buchholz F, Shirahige K, Nasmyth K. Protein phosphatase 2A protects centromeric sister chromatid cohesion during meiosis I. Nature 2006; 441:53-61; PMID:16541024; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature04664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clyne RK, Katis VL, Jessop L, Benjamin KR, Herskowitz I, Lichten M, Nasmyth K. Polo-like kinase Cdc5 promotes chiasmata formation and cosegregation of sister centromeres at meiosis I. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5:480-485; PMID:12717442; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee BH, Amon A. Role of Polo-like kinase CDC5 in programming meiosis I chromosome segregation. Science 2003; 300:482-486; PMID:12663816; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1081846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rumpf C, Cipak L, Dudas A, Benko Z, Pozgajova M, Riedel CG, Ammerer G, Mechtler K, Gregan J. Casein kinase 1 is required for efficient removal of Rec8 during meiosis I. Cell Cycle 2010; 9:2657-62; PMID:20581463; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.9.13.12146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katis VL, Lipp JJ, Imre R, Bogdanova A, Okaz E, Habermann B, Mechtler K, Nasmyth K, Zachariae W. Rec8 phosphorylation by casein kinase 1 and Cdc7-Dbf4 kinase regulates cohesin cleavage by separase during meiosis. Dev Cell 2010; 18:397-409; PMID:20230747; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barr FA, Silljé HH, Nigg EA. Polo-like kinases and the orchestration of cell division. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004; 5:429-40; PMID:15173822; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tong C, Fan HY, Lian L, Li SW, Chen DY, Schatten H, Sun QY. Polo-like kinase-1 is a pivotal regulator of microtubule assembly during mouse oocyte meiotic maturation, fertilization, and early embryonic mitosis. Biol Reprod 2002; 67:546-54; PMID:12135894; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod67.2.546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solc P, Kitajima TS, Yoshida S, Brzakova A, Kaido M, Baran V, Mayer A, Samalova P, Motlik J, Ellenberg J. Multiple requirements of Plk1 during mouse oocyte maturation. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0116783; PMID:25658810; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0116783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordan PW, Karppinen J, Handel MA. Polo-like kinase is required for synaptonemal complex disassembly and phosphorylation inmouse spermatocytes. J Cell Sci 2012; 125:5061-72; PMID:22854038; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.105015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Weerdt BC, van Vugt MA, Lindon C, Kauw JJ, Rozendaal MJ, Klompmaker R, Wolthuis RM, Medema RH. Uncoupling anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome activity from spindle assemblycheckpoint control by deregulating polo-like kinase 1. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25:2031-2044; PMID:15713655; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.25.5.2031-2044.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang YJ, Ma S, Terada Y, Erikson RL. Phosphorylation of threonine 210 and the role of serine 137 in the regulation of mammalian polo-like kinase. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:44115-20; PMID:12207013; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M202172200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seki A, Coppinger JA, Jang CY, Yates JR, Fang G. Bora and the kinase Aurora a cooperatively activate the kinase Plk1 and control mitotic entry. Science 2008; 320:1655-58; PMID:18566290; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1157425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei Y, Yu L, Bowen J, Gorovsky MA, Allis CD. Phosphorylation of histone H3 is required for proper chromosome condensation andsegregation. Cell 1999; 97:99-109; PMID:10199406; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80718-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gu L, Wang Q, Wang CM, Hong Y, Sun SG, Yang SY, Wang JG, Hou Y, Sun QY, Liu WQ. Distribution and expression of phosphorylated histone H3 during porcine oocyte maturation. Mol Reprod Dev 2008; 75:143-49; PMID:17342732; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/mrd.20706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.LaRosa C, Downs SM. Stress stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase and meiotic resumption in mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod 2006; 74:585-92; PMID:16280415; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod.105.046524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J, Shen C, Wang T, Quan J. Structural basis for the inhibition of Polo-like kinase 1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2013; 20:1047-53; PMID:23893132; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macůrek L, Lindqvist A, Lim D, Lampson MA, Klompmaker R, Freire R, Clouin C, Taylor SS, Yaffe MB, Medema RH. Polo-like kinase-1 is activated by aurora A to promote checkpoint recovery. Nature 2008; 455:119-23; PMID:18615013; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruinsma W, Macurek L, Freire R, Lindqvist A, Medema RH. Bora and Aurora-A continue to activate Plk1 in mitosis. J Cell Sci 2014; 127:801-11; PMID:24338364; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.137216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qian YW, Erikson E. Maller JL. Purifcation and cloning of a protein kinase that phosphorylates and activates the polo-like kinase Plx1. Science 1998; 282:1701-04; PMID:9831560; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.282.5394.1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ellinger-Ziegelbauer H, Karasuyama H, Yamada E, Tsujikawa K, Todokoro K, Nishida E. Ste20-like kinase (SLK), a regulatory kinase for polo-like kinase (Plk) during the G2/M transition in somatic cells. Genes Cells 2000; 5:491-98; PMID:10886374; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelm O, Wind M, Lehmann WD, Nigg EA. Cell cycle-regulated phosphorylation of the Xenopus polo-like kinase Plx1. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:25247-56; PMID:11994303; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M202855200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee J, Okada K, Ogushi S, Miyano T, Miyake M, Yamashita M. Loss of Rec8 from chromosome arm and centromere region is required for homologous chromosome separation and sister chromatid separation, respectively, in mammalian meiosis. Cell Cycle 2006; 5:1448-55; PMID:16855401; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.5.13.2903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steegmaier M, Hoffmann M, Baum A, Lénárt P, Petronczki M, Krssák M, Gürtler U, Garin-Chesa P, Lieb S, Quant J, Grauert M, Adolf GR, Kraut N, Peters JM, Rettig WJ. BI 2536, a potent and selective inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1, inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Curr Biol 2007; 17:316-22; PMID:17291758; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lénárt P, Petronczki M, Steegmaier M, Di Fiore B, Lipp JJ, Hoffmann M, Rettig WJ, Kraut N, Peters JM. The small-molecule inhibitor BI 2536 reveals novel insights into mitotic roles of polo-like kinase 1. Curr Biol 2007; 17:304-15; PMID:Can't; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park JE, Soung NK, Johmura Y, Kang YH, Liao C, Lee KH, Park CH, Nicklaus MC, Lee KS. Polo-box domain: a versatile mediator of polo-like kinase function. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010; 67:1957-70; PMID:20148280; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-010-0279-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma W, Baumann C, Viveiros MM. NEDD1 is crucial for meiotic spindle stability and accurate chromosome segregation inmammalian oocytes. Dev Biol 2010; 339:439-50; PMID:20079731; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lane HA, Nigg EA. Antibody microinjection reveals an essential role for human polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) in the functional maturation of mitotic centrosomes. J Cell Biol 1996; 135:1701-13; PMID:8991084; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haren L, Stearns T, Lüders J. Plk1-dependent recruitment of gamma-tubulin complexes to mitotic centrosomes involves multiple PCM components. PLoS One 2009; 4: e5976; PMID:19543530; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0005976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee K, Rhee K. PLK1 phosphorylation of pericentrin initiates centrosome maturation at the onset of mitosis. J Cell Biol 2011; 195:1093-101; PMID:22184200; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201106093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X, Chen Q, Feng J, Hou J, Yang F, Liu J, Jiang Q, Zhang C. Sequential phosphorylation of Nedd1 by Cdk1 and Plk1 is required for targeting of the gTuRC to the centrosome. J. Cell Sci 2009; 122:2240-51; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.042747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sdelci S, Schütz M, Pinyol R, Bertran MT, Regué L, Caelles C, Vernos I, Roig J. Nek9 phosphorylation of NEDD1/GCP-WD contributes to Plk1 control of γ-tubulin recruitment to the mitotic centrosome. Curr Biol 2012; 22:1516-23; PMID:22818914; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mailhes JB, Hilliard C, Fuseler JW, London SN. Okadaic acid, an inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A, induces premature separation ofsister chromatids during meiosis I and aneuploidy in mouse oocytes in vitro. Chromosome Res 2003; 11:619-31; PMID:14516070; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1024909119593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.