Abstract

Background. A monovalent human rotavirus vaccine (RV1) was introduced in Botswana in July 2012. We assessed the impact of RV1 vaccination on childhood gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations and deaths in 2013 and 2014.

Methods. We obtained data from registers of 4 hospitals in Botswana on hospitalizations and deaths from gastroenteritis, regardless of cause, among children <5 years of age. Gastroenteritis hospitalizations and deaths during the prevaccine period (January 2009–December 2012) were compared to the postvaccine period (January 2013–December 2014). Vaccine coverage was estimated from data collected through a concurrent vaccine effectiveness study at the same hospitals.

Results. By December 2014, coverage with ≥1 dose of RV1 was an estimated 90% among infants <1 year of age and 76% among children 12–23 months of age. In the prevaccine period, the annual median number of gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations in children <5 years of age was 1212, and of gastroenteritis-related deaths in children <2 years of age was 77. In the postvaccine period, gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations decreased by 23% (95% confidence interval [CI], 16%–29%) to 937, and gastroenteritis-related deaths decreased by 22% (95% CI, −9% to 44%) to 60. Declines were most prominent during the rotavirus season (May–October) and among infants <1 year of age, with reductions of 43% (95% CI, 34%–51%) in gastroenteritis hospitalizations and 48% (95% CI, 11%–69%) in gastroenteritis deaths.

Conclusions. Following introduction of RV1 into the national immunization program, significant declines in hospitalizations and deaths from gastroenteritis were observed among children in Botswana, suggestive of the beneficial public health impact of rotavirus vaccination.

Keywords: rotavirus vaccine, mortality, morbidity

Diarrheal diseases remain a leading cause of death in children <5 years of age [1, 2]. Rotavirus, the single most important cause of severe childhood diarrhea globally, accounts for about one-third of all deaths attributable to diarrhea, and 5% of all childhood deaths [3]. The vast majority of deaths from rotavirus occur in low-income countries, with more than half occurring in Africa [3]. Rotavirus infections also put considerable burden on healthcare systems, accounting for 40% of all gastroenteritis hospitalizations for children aged <5 years worldwide, including in African countries [4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends global use of rotavirus vaccines (Rotarix, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium; or RotaTeq, Merck Vaccines, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey) to prevent severe gastroenteritis due to rotavirus [5]. Whereas clinical trials of these vaccines demonstrated high efficacy against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in high- and middle-income countries in the Americas and Europe (85%–98%), trials in low- and middle-income countries in Africa and Asia have demonstrated lower efficacy (61%–64% and 48%, respectively) [6–10]. Despite lower efficacy in low-resource settings, the benefits of vaccination could be substantial in countries with a high baseline burden of severe rotavirus disease. Significant declines in all-cause gastroenteritis mortality and hospitalizations among children <5 years of age have been observed following rotavirus vaccine introduction in a few early-adopter countries with low child mortality [11–15]. The variation in efficacy by national gross domestic product [16] underscores the importance of monitoring the impact of rotavirus vaccination in low-income, high-mortality settings during routine programmatic use, where vaccine performance may differ from the optimal conditions of clinical trials.

Botswana is a middle-income African country [17], although this distinction belies relatively high child mortality (47 deaths per 1000 children aged <5 years in 2013) [18], and high human immunodeficiency virus prevalence (16.9% of the population aged ≥6 weeks) [19]. Diarrheal illnesses, including rotavirus gastroenteritis, cause relatively high morbidity and mortality in Botswana in comparison with other African countries [20, 21]. In July 2012, the Botswana Ministry of Health introduced a monovalent rotavirus vaccine (RV1; Rotarix) into its routine immunization program, recommending a 2-dose series at 2 and 3 months of age. We assessed trends in all-cause gastroenteritis hospitalizations and deaths among young children admitted to 4 public hospitals in Botswana before and after rotavirus vaccine implementation.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective study conducted from September 2014 to January 2015 at the pediatric wards of 4 hospitals in Botswana: Princess Marina Hospital in Gaborone, Nyangabgwe Referral Hospital in Francistown, Letsholathebe II Hospital in Maun, and Bobonong Primary Hospital in Bobonong. Princess Marina Hospital and Nyangabgwe Referral Hospital are the country's 2 tertiary referral centers, Letsholathebe II Hospital is a district hospital serving northern Botswana, and Bobonong Primary Hospital is a small primary hospital. These sites are located in the northeast and in the capital, where the majority of the population is located, and were chosen to include a range of geographic and socioeconomic locales, serving populations with varying health indicators in Botswana. The Health Research Development Committee of Botswana and the Human Subjects Committees of the University of Pennsylvania and McMaster University approved the study protocol.

Vaccine Coverage

Vaccination coverage was estimated from data prospectively collected in June 2013 to April 2015 through a concurrent case-control study of vaccine effectiveness against rotavirus admission conducted at the same study hospitals. Vaccination rates were calculated among infants 4–11 months of age and children 12–23 months of age admitted with gastroenteritis who tested negative for rotavirus (ie, “test-negative” controls). Vaccination status was determined by review of the children's vaccination cards.

Data Extraction

We reviewed pediatric ward admission logbooks from January 2009 to December 2014. We recorded every gastroenteritis-related admission among children <5 years of age to the pediatric wards, noting the patient age and outcome of admission (discharged home, transferred, or deceased). Admissions were considered related to gastroenteritis of any cause if the diagnosis listed in the register was gastroenteritis, acute gastroenteritis, acute diarrheal disease, gastroenteritis and dehydration, diarrhea, vomiting, enteritis, gastritis, febrile gastroenteritis, food poisoning, or dysentery. Cases for which there were additional diagnoses were included.

We excluded cases with the following listed diagnoses: chronic gastroenteritis, chronic enteritis, chronic diarrhea, vomiting secondary to toxic ingestion, or vomiting secondary to ingestion of wild fruits or plants. We also excluded cases where the patient age was not recorded (2.0% of gastroenteritis cases recorded at all sites).

If the outcome of admission was not recorded in the admission registers, the outcome was sought through review of daily rounding books and, if patients were transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), the hospital ICU registers. Ward death registers were reviewed to ensure that all gastroenteritis-related deaths among children admitted to the pediatric wards had been ascertained in our review of the admission logbooks. For the months during which admission registers were not available, numbers of gastroenteritis admissions and deaths were obtained through review of medical records data and death registers. Complete admission data were available for 170 of 192 site-months (89%) during the prevaccine period and 96 of 96 site-months (100%) during the postvaccine period. Complete mortality data were available for 185 of 192 site-months (96%) during the prevaccine period and 96 of 96 site-months (100%) during the postvaccine period.

Data Analysis

The monthly number of admissions and deaths related to all-cause gastroenteritis were stratified by age group: 0–11 months, 12–23 months, 24–59 months, and all ages (0–59 months). Incidence rates could not be determined as there were no reliable data regarding the catchment population of the study hospitals. To minimize the impact of gaps in admissions and mortality data on the overall analysis, the totals of median monthly admissions were used, which effectively imputes data for any missing months. Medians were determined for each calendar month during the prevaccine years 2009–2012, and during the postvaccine years 2013–2014. The year 2012 was included in the prevaccine period as the vaccine was introduced midyear during the rotavirus season, and given a gradual uptake in coverage among eligible infants, a significant impact of the vaccine during that year would not be expected. Annual numbers were calculated as a sum of the monthly medians over the calendar year. Rotavirus season numbers were calculated as a sum of the monthly medians over the rotavirus season, defined as May to October based on data from 4 years of ongoing hospital-based active rotavirus surveillance [20]. We compared the annual median number of admissions and deaths during the pre- and postvaccine years, stratified by age group. Because few deaths (n = 16) occurred in children ≥2 years of age over the entire study period, the mortality analyses was restricted to children aged <2 years. We also compared the median numbers of admissions and deaths, stratified by age, during the prevaccine rotavirus seasons, first with the postvaccine medians, and then by each postvaccine year individually. Percentage reductions and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Poisson regression analyses comparing medians in admissions and deaths in prevaccine and postvaccine years. Finally, the monthly total gastroenteritis-related admissions and deaths for children <2 years of age during each of the months of 2013 and 2014 were compared with the prevaccine monthly medians, as well as the minimum and maximum numbers for each of those months, and assessed according to rotavirus season and non–rotavirus season periods. All analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington) and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute) software.

Hospitalizations From Ingestions

To assess possible bias from changes in the catchment population served by the study hospitals over time, we compared trends in admissions related to gastroenteritis with those of diagnoses related to ingestions, a condition that was unlikely to be affected by rotavirus vaccination. Diagnoses for ingestions included drug/toxin ingestion, intoxication, poisoning, drug overdose, chemical pneumonitis, extrapyramidal signs, and foreign body ingestion. Some common examples included paraffin ingestion, elephant ear ingestion, or paracetamol overdose. Diagnoses that were excluded from the count of ingestion cases included food poisoning or food intoxication, foreign body (in the ear, eye, or nose), and traditional medicine ingestion. Complete data were available for 150 of 192 site-months (78%) during the prevaccine period and 94 of 96 site-months (98%) during the postvaccine period.

RESULTS

Vaccine Coverage

Vaccine coverage with at least 1 dose of RV1 during 2013 and 2014 was an estimated 90% (212/235) among infants 4–11 months of age, and 76% (90/118) among children 12–23 months of age (Table 1). Among infants aged 4–11 months, 75% (176/235) were fully vaccinated with 2 doses, and among children aged 12–23 months, 64% (76/118) were fully vaccinated.

Table 1.

Gastroenteritis-Related Mortality Among Children <2 Years of Age During the Postvaccine Period (2013–2014) Compared With the Prevaccine Baseline Period (2009–2012), as a Sum of Monthly Medians by Age Group, From 4 Hospitals in Botswana

| Age Group | Vaccine Coverage (≥1 Dose), in 2013–2014a |

Annual Gastroenteritis-Related Deaths |

Rotavirus Season Gastroenteritis-Related Deaths |

Non–Rotavirus Season Gastroenteritis-Related Deaths |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevaccine | Postvaccine | Absolute Reduction |

% Reduction (95% CI) |

Prevaccine | Postvaccine | % Reduction (95% CI) |

Prevaccine | Postvaccine | % Reduction (95% CI) |

||

| 0–23 mo | 85% | 77 | 60 | 17 | 22 (−9 to 44) | 44 | 27 | 39 (1–62) | 33 | 33 | 0 (−62 to 38) |

| 0–11 mo | 90% | 69 | 47 | 22 | 32 (1–53) | 40 | 21 | 48 (11–69) | 30 | 26 | 13 (−47 to 49) |

| 12–23 mo | 76% | 8 | 13 | −6 | −73 (−292 to 33) | 5 | 6 | −20 (−293 to 66) | 3 | 7 | −133 (−802 to 40) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Based on 231 infants 4–11 months of age and 112 children 12–23 months of age test-negative for rotavirus admitted during 2013 and 2014 at participating pediatric hospitals.

Gastroenteritis-Related Deaths

In total, 359 gastroenteritis-related deaths occurred among children <2 years of age during the prevaccine years 2009–2012, 303 (84%) of which occurred among infants, and 218 (61%) of which occurred during the rotavirus season (May–October). During the prevaccine baseline period, an annual median of 77 deaths among children <2 years of age were related to gastroenteritis (Table 1). Total annual gastroenteritis-related deaths in the prevaccine years for children <2 years of age were 72 in 2009, 84 in 2010, 97 in 2011, and 106 in 2012. In the postvaccine period, the annual median of deaths among children <2 years of age decreased to 60 deaths, corresponding to a reduction of 22% (95% CI, −9% to 44%) from the prevaccine annual median. This included a 32% (95% CI, 1%–53%) decrease in the annual median of gastroenteritis deaths among infants <1 year of age. The reduction in deaths was most prominent during the rotavirus season. During rotavirus season months, a median of 27 deaths occurred among children <2 years of age in the postvaccine period—a 39% reduction (95% CI, 1%–62%) from the baseline median number of 44 deaths. Among infants <1 year of age, a median of 21 deaths occurred during the rotavirus season in the postvaccine period—a 48% reduction (95% CI, 11%–69%) from the prevaccine median of 40 deaths.

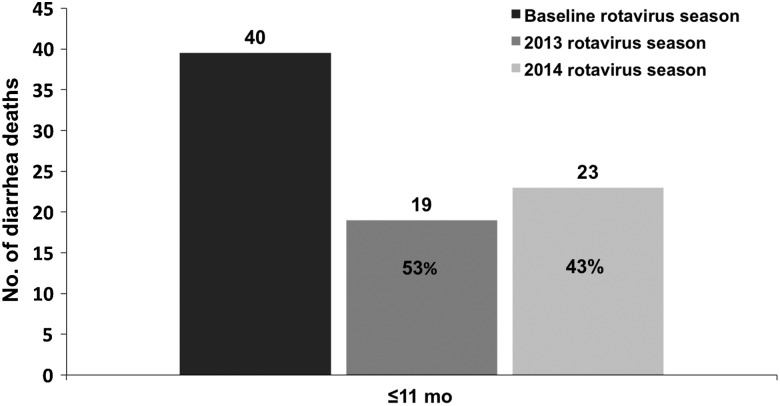

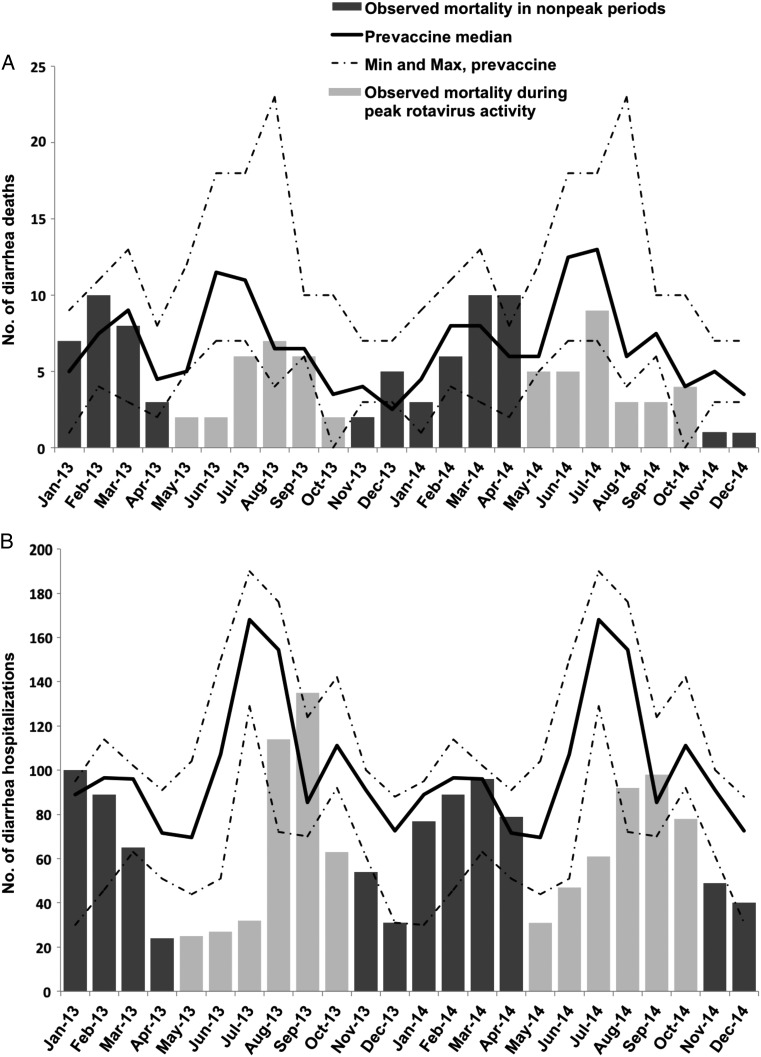

Assessing the postvaccine rotavirus seasons individually, reductions in infant deaths were sustained over the 2013 and 2014 rotavirus seasons (Figure 1). The greatest declines in deaths from gastroenteritis among children <2 years of age in 2013 and 2014 occurred during the rotavirus seasons (Figure 2A). During the non–rotavirus season months, the number of deaths was consistent with prevaccine medians.

Figure 1.

Infant all-cause gastroenteritis-related deaths during the 2013 and 2014 rotavirus seasons compared with the 2009–2012 prevaccine baseline rotavirus seasons, as a sum of monthly medians and with percentage reductions from baseline, from 4 hospitals in Botswana.

Figure 2.

Seasonal variation in gastroenteritis-related deaths (A) and hospitalizations (B) among children 0–23 months of age, with comparison of 2013–2014 totals to prevaccine medians, from 4 hospitals in Botswana.

Gastroenteritis-Related Hospitalizations

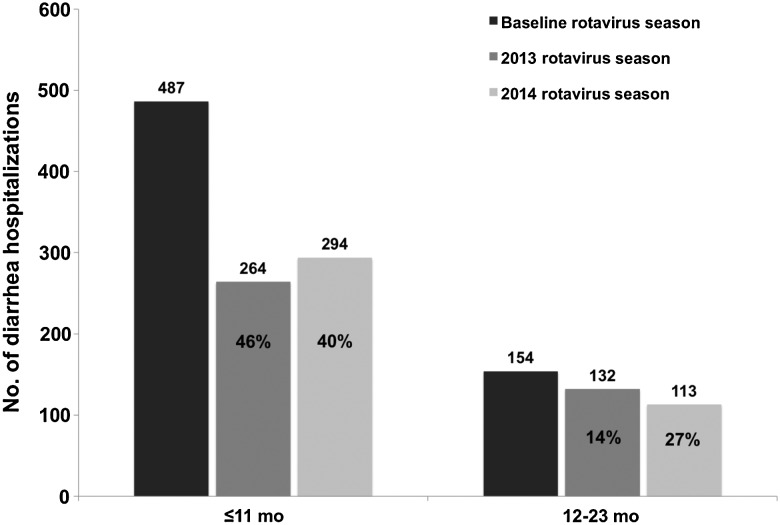

In total, 4440 gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations occurred among children <5 years of age during the prevaccine years 2009–2012, 2955 (67%) of which occurred among infants, and 2650 (60%) of which occurred during the rotavirus season (May–October). Post–vaccine introduction, 1873 gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations were recorded in 2013–2014. During the prevaccine baseline period, an annual median of 1212 hospitalizations related to gastroenteritis occurred among children <5 years of age (Table 2). Total annual gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations in the prevaccine years for children <5 years of age were 1025 in 2009, 1241 in 2010, 1084 in 2011, and 1090 in 2012. Annual gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations decreased by 23% (95% CI, 16%–29%) from the prevaccine annual median to 937 (904 in 2013 and 969 in 2014) in the postvaccine period, including a 33% (95% CI, 26%–40%) decrease in gastroenteritis admissions among infants. The reduction in gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations was most prominent during the rotavirus season. The median number of hospitalizations among children <5 years of age during rotavirus season months in the prevaccine period was 696, compared to 464 in the postvaccine period, corresponding to a 33% reduction (95% CI, 25%–41%) overall, and a 43% reduction (95% CI, 34%–51%) among infants. During 2013–2014, seasonal reductions were less pronounced among children 12–23 months of age (20% [95% CI, −1% to 37%]), and were not evident among those aged 24–59 months.

Table 2.

Gastroenteritis-Related Hospitalizations Among Children <5 Years of Age During the Postvaccine Period (2013–2014) Compared With the Prevaccine Baseline Period (2009–2012), as a Sum of Monthly Medians by Age Group, From 4 Hospitals in Botswana

| Age Group | Annual Gastroenteritis-Related Hospitalizations |

Rotavirus Season Gastroenteritis-Related Hospitalizations |

Non–Rotavirus Season Gastroenteritis-Related Hospitalizations |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevaccine | Postvaccine | % Reduction (95% CI) | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | % Reduction (95% CI) | Prevaccine | Postvaccine | % Reduction (95% CI) | |

| All ages (0–59 mo) | 1212 | 937 | 23 (16–29) | 696 | 464 | 33 (25–41) | 517 | 473 | 9 (−4 to 19) |

| 0–11 mo | 817 | 545 | 33 (26–40) | 487 | 279 | 43 (34–51) | 331 | 266 | 20 (6–32) |

| 12–23 mo | 272 | 253 | 7 (−10 to 21) | 154 | 123 | 20 (−1 to 37) | 118 | 131 | −11 (−42 to 13) |

| 24–59 mo | 123 | 139 | −13 (−44 to 11) | 55 | 63 | −14 (−64 to 20) | 68 | 76 | −12 (−55 to 19) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Assessing postvaccine rotavirus seasons individually, reductions in infant hospitalizations with gastroenteritis were sustained over the 2013 and 2014 rotavirus seasons (Figure 3). A 27% decrease in gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations among children 12–23 months of age was noted in 2014, the first full year that this age group would have been eligible to receive the vaccine. Among children <2 years of age, peak gastroenteritis hospitalizations during the rotavirus season months were blunted in 2013 and 2014, compared with the median number of hospitalizations during the same months in the baseline period (Figure 2B).

Figure 3.

All-cause gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations among infants and children aged 12–23 months during the 2013 and 2014 rotavirus seasons compared with the 2009–2012 prevaccine baseline rotavirus seasons, as a sum of monthly medians and with percentage reductions from baseline, from 4 hospitals in Botswana.

Hospitalizations From Ingestions

No declines were noted in pediatric hospitalizations related to ingestions over the study period. During prevaccine baseline years, the annual median number of hospitalizations related to ingestions was 256. In 2013 and 2014, respectively, 322 and 269 admissions related to ingestions occurred.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to demonstrate the impact of rotavirus vaccination on childhood mortality from gastroenteritis in Africa, where more than half of global rotavirus deaths occur. In the 2 years following rotavirus vaccine introduction in Botswana, there was a 22% annual reduction in deaths related to gastroenteritis among children <2 years of age, and a 48% reduction in infant deaths related to gastroenteritis during the rotavirus season at the 4 study hospitals. Over the same period there was a 23% reduction in annual hospitalizations related to gastroenteritis among children <5 years of age annually, and a 43% reduction in infant hospitalizations during the rotavirus season. The findings outlined here are consistent with mortality and hospitalization trends documented in middle-income countries in Latin America after rotavirus vaccine introduction, where declines in deaths and hospitalizations ranged from 22% to 38% and 11% to 40%, respectively [11, 13, 14]. As in this study, the decline in diarrhea-related mortality was sustained over a 2-year period after the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine. Our study suggests the powerful public health value of rotavirus vaccination during routine use in a high-mortality setting, and strongly supports WHO recommendations for continued rollout of rotavirus vaccines in other African nations with high burdens of severe rotavirus disease.

While the scope of this study evaluates the declines in mortality and hospitalizations from all-cause gastroenteritis, several key findings suggest that the observed reductions may be due to rotavirus vaccination. First, declines were concentrated during the rotavirus season months, with the great majority of annual reductions occurring in May through October, as has been described in other settings after introduction of rotavirus vaccination [13–15, 22]. Second, declines in deaths and hospitalizations were most pronounced among infants, which correlated with the higher burden of severe rotavirus in this age group [20], as well as with the higher vaccine coverage among infants during the study period. Last, reductions during rotavirus seasons in individual years were noted sequentially in age groups as they became increasingly vaccinated. Initial declines (in 2013) in hospitalizations and deaths were mainly seen among infants, the first birth cohort eligible to be vaccinated. By 2014, a decline of 27% was noted in gastroenteritis hospitalizations among children aged 12–23 months, when coverage increased among older children.

Several limitations should be considered. First, there were gaps in the data available from admission registers. These were supplemented as completely as possible with hospital records that should provide comparable data. By analyzing totals of median monthly admissions, the impact of missing months on the overall analysis was minimized. Importantly, the trends observed in this study were seen at all study sites. The most complete data (96% prevaccine and 100% postvaccine) were available for the mortality analysis, which demonstrated the greatest impact of the rotavirus vaccine. Second, underreporting of deaths due to gastroenteritis was likely, as this study did not capture child deaths that occurred at home, in the emergency department, or after direct admission to the ICU. Such underreporting is unlikely to have changed significantly between the prevaccine and postvaccine time periods. Third, there is the possibility of secular variation underlying the declines seen in hospitalizations and mortality from gastroenteritis, including improvements in sanitation, changes in hospital referral patterns, or advances in prehospital or in-hospital care. The prevaccine yearly total hospitalizations and deaths were stable and increasing, respectively, suggesting that there was not a preexisting secular trend prior to implementation of RV1 vaccination. To our knowledge, there were no abrupt changes in hospital referral patterns or care. Such changes, furthermore, are unlikely to explain the large reductions in hospitalizations and mortality observed over a short period of time, which were concentrated during the rotavirus season and sustained over 2 years across all sites. We were not able to calculate incidence rates for this study as no reliable catchment population data were available. However, we believe that the catchment population for the study hospitals would have remained relatively stable over the study period; this is supported by the finding that hospitalizations for ingestions were stable or increased over the study.

In summary, marked declines in hospitalizations and deaths from pediatric gastroenteritis, primarily among infants, were observed during the first 2 complete rotavirus seasons after the addition of a monovalent rotavirus vaccine to the childhood immunization schedule in Botswana. In upcoming years, as the immunization program matures, the observed impact will likely extend to older age cohorts in the country. Continued surveillance is key to fully ascertain the effect of rotavirus vaccination on the burden of childhood diarrheal illness in Botswana. Our findings are consistent with a benefit from rotavirus vaccination in protecting against the most severe and fatal forms of rotavirus gastroenteritis, and strongly support WHO recommendations for global rotavirus vaccine use.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the patients and staff of Princess Marina Hospital, Nyangabgwe Referral Hospital, Letsholathebe II Hospital, and Bobonong Primary Hospital. This work is dedicated to the memory of Dr Melissa Ketunuti. As a compassionate pediatrician and researcher, she worked to improve health for vulnerable children in Botswana and around the world, and she continues to inspire our work.

Author contributions. L. A. E., P. A. G., and J. E. T. performed the data analysis. All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript and agreed to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of PATH, the CDC Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, or GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance.

Financial support. This work was supported by the CDC Foundation. This publication was made possible through core services and support from the Penn Center for AIDS Research, a National Institutes of Health–funded program (grant number P30 AI 045008).

Supplement sponsorship. This article appears as part of the supplement “Health Benefits of Rotavirus Vaccination in Developing Countries,” sponsored by PATH and the CDC Foundation through grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL et al. . Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:1969–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S et al. . Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2012; 379:2151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C et al. . 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mwenda JM, Tate JE, Parashar UD et al. . African Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:S6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Rotavirus vaccines: an update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009; 84:533–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vesikari T, Matson DO, Dennehy P et al. . Safety and efficacy of a pentavalent human-bovine (WC3) reassortant rotavirus vaccine. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pérez-Schael I, Velázquez FR et al. . Safety and efficacy of an attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madhi SA, Cunliffe NA, Steele D et al. . Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armah GE, Sow SO, Breiman RF et al. . Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376:606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaman K, Anh DD, Victor JC et al. . Efficacy of pentavalent rotavirus vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis in infants in developing countries in Asia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 376:615–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.do Carmo GMI, Yen C, Cortes J et al. . Decline in diarrhea mortality and admissions after routine childhood rotavirus immunization in Brazil: a time-series analysis. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1001024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yen C, Armero Guardado JA, Alberto P et al. . Decline in rotavirus hospitalizations and health care visits for childhood diarrhea following rotavirus vaccination in El Salvador. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:S6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quintanar-Solares M, Yen C, Richardson V, Esparza-Aguilar M, Parashar UD, Patel MM. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on diarrhea-related hospitalizations among children <5 years of age in Mexico. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:S11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson V, Hernandez-Pichardo J, Quintanar-Solares M et al. . Effect of rotavirus vaccination on death from childhood diarrhea in Mexico. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gastanaduy PA, Sanchez-Uribe E, Esparza-Aguilar M et al. . Effect of rotavirus vaccine on diarrhea mortality in different socioeconomic regions of Mexico. Pediatrics 2013; 131:e1115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson EAS, Glass RI. Rotavirus: realising the potential of a promising vaccine. Lancet 2010; 376:568–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Bank, ed. Botswana—data. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/country/botswana Accessed 15 January 2016.

- 18.United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality Report 2014. United Nations Children's Fund. New York. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/media/files/Levels_and_Trends_in_Child_Mortality_2014.pdf. Accessed 15 January 2016.

- 19.Statistics Botswana. Preliminary results—Botswana AIDS Impact Survey IV(BAIS IV), Gaborone: Statistics Botswana, 2013.

- 20.Welch H, Steenhoff AP, Chakalisa U et al. . Hospital-based surveillance for rotavirus gastroenteritis using molecular testing and immunoassay during the 2011 season in Botswana. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32:570–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pernica JM, Steenhoff AP, Welch H et al. . Correlation of clinical outcomes with multiplex molecular testing of stool from children admitted to hospital with gastroenteritis in Botswana. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc 2015; pii:piv028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Msimang VMY, Page N, Groome MJ et al. . Impact of rotavirus vaccine on childhood diarrheal hospitalization after introduction into the South African public immunization program. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32:1359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]