Abstract

Nursery rearing of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) alters behaviors but may be necessitated by maternal rejection or death, for research protocols, or for derivation of SPF colonies. The Tulane National Primate Research Center maintains a nursery-reared colony that is free from 9 pathogens as well as a mother-reared colony free from 4 pathogens, thus affording an opportunity to assess the outcomes of differential rearing. Nursery-reared macaques had continuous contact with 2 peers and an artificial surrogate (peer rearing). Focal sampling (432 h) was collected on the behavior of 32 peer-reared and 40 mother-reared subjects (age, 1 to 10 y; immature group, younger than 4 y; adult group 4 y or older). All animals were housed outdoors in like-reared social groups of 3 to 8 macaques. Contrary to expectation, no rearing effects on affiliative or agonistic social behaviors were detected. Compared with mother-reared subjects, peer-reared macaques in both age classes had elevated levels of abnormal appetitive, abnormal self-directed, and eating behaviors and lower levels of locomoting and vigilance (highly alert to activities in surrounding environment); a trend toward reduced foraging was detected. Immature but not adult peer-reared monkeys demonstrated more enrichment-directed behavior and drinking and a trend toward more anxiety-related behavior and inactivity. No new rearing effects were detected in adults that had not been detected in immature subjects. Results suggest that modern peer-rearing practices may not result in inevitable perturbations in aggressive, rank-related, sexual, and emotional behavior. However, abnormal behaviors may be lifelong issues once they appear.

Abbreviations: MR, mother reared; PR, peer reared

Rearing history is an important consideration when addressing the needs of macaques in captivity. In breeding colonies, nursery rearing may be a necessary management intervention due to maternal incompetence or death and when a foster dam cannot be identified. In addition, nursery rearing may be required for specific types of research. Decades of research broadly indicate that a combination of an artificial surrogate, human interaction, and social contact with peers is the best way to rear macaques in the nursery, a strategy that will avoid the devastating effects of total-isolation rearing12,19,20 and allow the animals to successfully integrate into and breed in larger social groups.34 However, even with modern nursery-rearing practices, the behavioral and physiologic profiles of nursery-reared macaques differ from those of macaques that have been raised with their mothers in a social group. Behaviorally, nursery rearing is associated with an increased risk for developing repetitive stereotypies, self-biting, self-wounding, and noninjurious self-directed abnormal behavior.3,10,16,30,31,35,41 In addition, some evidence suggests that nursery rearing results in heightened anxiety13,21,42 and lower levels of environmental exploration.6 With regard to social behavior, nursery-reared macaques show decreased levels of grooming, play, and social reciprocity, and the presence of companions does not appear to buffer them from stress.26,42 In addition, nursery rearing is associated with increased fear and aggression.27,44 Sexual and maternal deficits may occur as well.15,17,18,38

In addition to effects on behavior, physiologic changes have been identified in macaques reared in the nursery setting. Differential rearing affects brain architecture involved in cognition,37 emotional processing25 and vulnerability to adverse effects of stress.40 Although evidence concerning rearing effects on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis is equivocal, differences including reduced levels of oxytocin, norepinephrine, and homovanillic acid in the cerebrospinal fluid have been reported.22,27,28,44 Studies have identified several indicators of immune system alterations in nursery-reared macaques, such as decreased proportions of cytotoxic and suppressor T cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased lymphocyte proliferation.9,29

With regard to social management in the nursery, strategies fall into 2 main categories: peer rearing, involves continuous cohousing, whereas surrogate–peer rearing involves brief periods of cohousing of otherwise singly housed infants. Although infants in both rearing conditions may be provided an inanimate surrogate, surrogate–peer-reared infants are housed for the majority of the time with the inanimate surrogate only, with the intention that infants’ need for clinging to an attachment figure will be directed toward the surrogate, even when peers are present. However, this distinction is generalized, and both nursery-rearing categories may involve variations across facilities. Moreover, a subset of the literature differentiates between these housing conditions and compares them. In comparison with surrogate–peer rearing, peer rearing is associated with lower levels of stereotypic and self-injurious behavior, 31,35,36 whereas surrogate-peer rearing appears to mitigate the increased anxiety observed in peer-reared subjects.12,20,40 In addition, surrogate–peer-reared macaques show less social clinging, fear, and aggression and more exploration and play than do their peer-reared counterparts.5,7,35,36

Although the literature on the nursery rearing of macaques is extensive, many of the studies concerning the behavioral effects of rearing involve both infants and older subadults or evaluations of behavior indoors and under test conditions. Therefore these populations need to be characterized more thoroughly under the conditions in which they are housed. The relative costs and benefits of the 2 forms of nursery rearing may vary with time and housing condition, especially when the ultimate goal is to maintain the animals long-term and for breeding purposes. For example, nursery-reared macaques may be eventually housed in small outdoor groups, particularly as part of the process of deriving SPF colonies,38 and the literature in the context of their behavior in a more naturalistic group setting is sparse.

The question of which nursery rearing practice optimally equips macaques with species-normative behaviors to live in an outdoor group-housed situation is best assessed by comparing mother-reared, peer-reared, and surrogate–peer-reared subjects in similar physical and social conditions. However, even when all 3 categories of animals are unavailable, comparing mother-reared with peer-reared macaques is valuable for assessing the downstream consequences of nursery-management decisions. The objective of the current study was to characterize the behavior of peer-reared, outdoor group-housed rhesus macaques compared with that of mother-reared, outdoor group-housed subjects. Although we expect broad social and reproductive competence in these animals, we test the prediction that peer rearing results in significant perturbations in social behavior as well as heightened anxiety. Characterizing this population is necessary for determining its behavioral needs. If the long-term effects of rearing mimic signs of current reduced wellbeing, it is difficult to assess the need for intervention and the expected response to that intervention. This assessment will allow us to measure the cost of management decisions designed to mitigate rearing-related abnormal behaviors, to predict or interpret the behavior of breeding groups consisting of peer-reared macaques, and ultimately, to contribute to the literature that may guide our ability to make evidence-based decisions regarding different nursery-rearing strategies. Furthermore, this study uses subjects of widely varied ages in both rearing categories to gain information on the long-term stability of rearing differences with increasing age.

Materials and Methods

All work was conducted at the Tulane National Regional Primate Center (Covington, LA) an AAALAC-accredited institution. Housing and care were provided in accordance with the standards set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals24 and the USDA's Animal Welfare Regulations.1 All study procedures and methods were preapproved by the Tulane University IACUC.

Rearing histories.

After removal from their dam, peer-reared (PR) infants were housed indoors with a soft cloth surrogate and were introduced into like-aged trios at 30 d of age. Because reducing the risks of development of self-injurious behavior was selected as top priority over the risk of excessive social clinging, peer housing was chosen over surrogate–peer housing. This choice was especially important because the colony was developed not only to be self-sustaining but also to generate subjects for research projects requiring indoor single caging, which dramatically influences the risks of self-injurious behavior.2,15,28 In addition, peer groups were provided age-appropriate toys and climbing apparatuses. Once they were eating solid food, the macaques received feeding enrichment daily. Nursery conditions were maintained on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle at an ambient temperature of 64 to 72 °F (17.8 to 22.2 °C) and 30% to 70% relative humidity. At 1 y of age, all PR infants were moved into social groups consisting of 6 to 9 like-reared counterparts housed in outdoor enclosures, to form expanded SPF breeding groups. For management purposes, some groups occasionally were divided into smaller subgroups over time, in response to viral status results or social incompatibilities.

All mother-reared (MR) animals were born to conventional (nonSPF) dams housed in large social groups in outdoor field cages. Field cages ranged from 0.13 to 0.5 acre and contained an average of 20 to 25 animals, which typically included several adult females, juveniles, and infants as well as 1 to 4 adult male macaques. Enclosures contained natural ground cover and a variety of structures for climbing, play, and shelter. Feeding enrichment was distributed 3 times each week. For the derivation process, infants were removed from their natal groups no earlier than 8 mo of age. Among study subjects, the age of removal of infants ranged between 8.0 and 17.2 mo (mean ± 1 SD, 11.6 ± 0.3 mo). Subsequently, they were placed into groups of like-age macaques and housed in outdoor run enclosures.

Study subjects.

The study included a total of 32 PR subjects (male, 12; female, 20) and 40 MR subjects (male, 12; F = 28). All were rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) housed at the center. Animals ranged in age from 1 to 10 y; age did not differ significantly between rearing groups (F1,38 = 1.25; P = 0.27).

Subject age was categorized into a dichotomous variable in keeping with the study design of sampling distinct populations. Animals that remained younger than 4 y throughout data collection were classified as immature (PR: n = 21; MR: n = 19), and animals that reached or exceeded the age of 4 y were classified as adult (PR: n = 11; MR: n = 21). In the immature age category, the mean age of PR subjects was 2.70 y (range, 2.17 to 3.29 y) and that for MR subjects was 2.50 y (range, 1.61 to 3.52 y). In the adult category, the mean age for PR macaques was 4.28 y (range, 4.16 to 4.68 y) and that for MR animals was 4.73 y (range, 4.01 to 9.69 y).

All MR subjects were selected from the center's SPF rhesus macaque colony. This colony was derived from the conventional breeding program to establish a colony that is seronegative for SIV, simian T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1, type D retrovirus, and B virus. From this population, an expanded SPF colony has been derived as well, to generate animals that are also seronegative for rhesus cytomegalovirus, rhesus rhadinovirus, simian virus 40, rhesus Epstein–Barr virus/lymphocryptovirus, and simian foamy virus. These viruses are a threat to human safety and may confound infectious disease research. Several infants (6 to 12 each year) born to SPF mothers were removed from their dams within 48 h to minimize exposure to these pathogens. All PR subjects in the current study were drawn from the center's expanded SPF derivation program.

Subject selection was based on similarity in group composition between rearing categories with regard to age, group size, and sex ratios. Subject and social group selection for study was further refined to include a wide range of ages so that sufficient subjects would be available to compare the effects of rearing on an immature population with those on a mature population. Groups comprised male and female macaques of similar ages. Infants born in these groups during the data collection period were not used as subjects of the current study. Social groups were together for at least 1 mo prior to the start of data collection (mean: MR subjects, 19.84 mo; PR subjects, 19.77 mo).

Peer-reared animals were housed in groups containing 3 to 6 animals in outdoor corncrib enclosures consisting of mesh walls and concrete flooring. The floor space area was 120.8 ft2 (11 m2), with a diameter of 12.3 ft (3.7 m) and a ceiling height of 10 ft (3.1 m). Mother-reared animals were housed in groups containing 3 to 8 macaques in outdoor run-style enclosures constructed of mesh and containing a gravel substrate; floor space was 289 ft2 (26.85 m2) with a ceiling height of 9 ft (2.7 m).

For all study animals, enclosures were furnished with perches and manipulanda. Fresh water was available at all times, and animals were fed nutritionally complete commercial monkey biscuits (Purina Diet 5037, PMI Feeds, St Louis, MO) once or twice daily, with feeding enrichment items distributed 3 times each week.

Data collection.

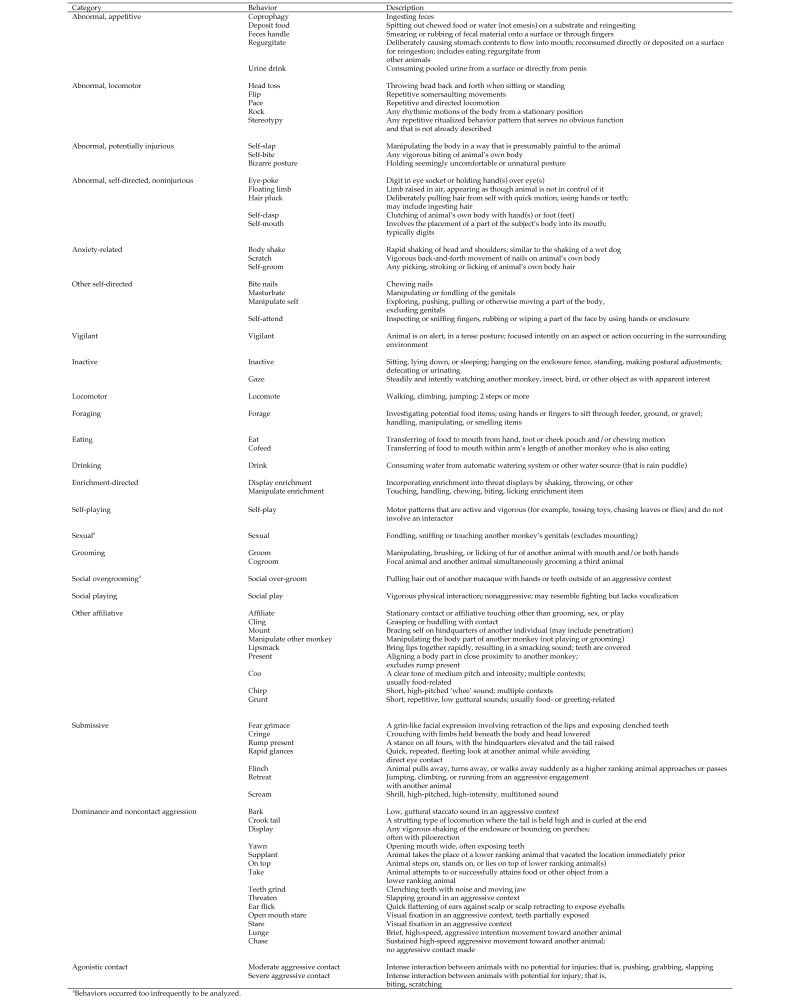

A total of 432 h of behavioral observations were conducted between July 2010 and January 2012 by a single observer (SAB). Observations took place between 0600 and 1200, with each animal observed for a total of 6 h. Focal animal observations (30 min each) with instantaneous sampling at 15-s intervals were conducted by using an ethogram containing 74 behaviors (Figure 1). When animals were engaged in multiple behaviors during the same interval, a single behavior was recorded according to the following predetermined descending order: abnormal > social > vocal > self-directed > enrichment-directed > other.

Figure 1.

Ethogram of behaviors and definitions used for data collection.

Statistical analysis.

Data were collapsed into 19 categories for analysis (see Figure 1 for operational definitions). Overgrooming, sexual behavior, and potentially self-injurious abnormal behavior were not analyzed because they occurred too rarely to be included. Point samples for individual subjects were pooled across observation periods, and statistical analyses were performed by using the percentage of samples at which each behavior occurred. Data were analyzed by using Statistica 10 (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK). Multivariate ANOVA were conducted with rearing and sex as grouping factors and with the α value set at 0.05. After an overall significant multivariate ANOVA result, univariate results were considered significant with a conservative α of 0.003 to adjust for multiple comparisons; trends were defined as 0.003 < P < 0.006. Data from immature and adult subjects were analyzed separately to control for differences due to age class and to evaluate whether differences persisted or resolved in the adult population.

Results

Immature subjects.

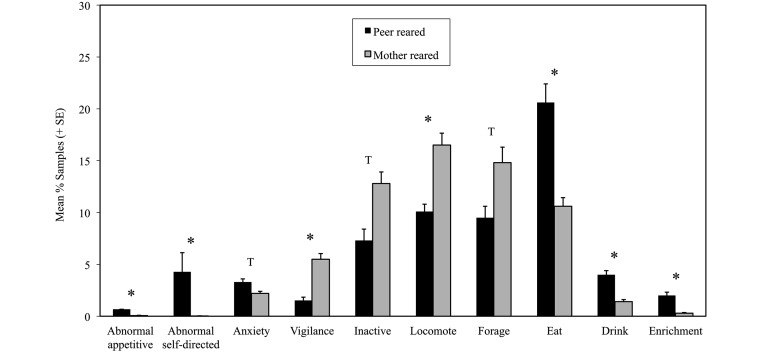

Multivariate ANOVA detected significant effects of sex (F19,18 = 3.07, P < 0.02) and rearing (F19,18 = 11.97, P < 0.0001) but no interaction effects (F19,18 = 1.19; P < 0.36). Overall, male immature macaques showed higher levels (mean ± 1 SD) of dominance and noncontact aggression (male, 3.10% ± 0.37%; female, 1.95% ± 0.13%; F19,18 = 11.50; P < 0.002). Table 1 presents the results for the main effects of rearing condition on behavior, with significant differences detected for 7 behaviors. Compared with MR immature macaques, PR immature subjects showed a greater proportion of time engaged in appetitive abnormal behavior, noninjurious self-directed abnormal behavior, eating, drinking, and enrichment-directed behaviors and tended toward increased anxiety-related behavior (Figure 2). In addition, PR immature macaques showed lower levels of locomotion and vigilance and trends toward reduced inactivity and foraging, compared with their MR counterparts. No differences in social behaviors, including social play, grooming, other affiliation, contact aggression, dominance/noncontact aggression, and submission, were noted between rearing groups. Furthermore, the incidence of abnormal locomotor behavior, species-appropriate self-directed behavior, and self-play did not differ between groups.

Table 1.

Main effects of peer rearing on the behaviors of immature and adult rhesus macaques

| F (1,36) | P | |

| Immature rhesus macaques | ||

| Abnormal, appetitivea | 20.76 | 0.0001 |

| Abnormal, locomotor | 0.86 | 0.36 |

| Noninjurious abnormala | 14.65 | 0.0005 |

| Anxiety-relatedb | 8.91 | 0.005 |

| Other self-directed behavior | 7.96 | 0.008 |

| Vigilancea | 32.58 | 0.0001 |

| Inactiveb | 9.41 | 0.004 |

| Locomotora | 17.15 | 0.0001 |

| Foragingb | 9.00 | 0.005 |

| Eatinga | 20.24 | 0.0001 |

| Drinkinga | 33.71 | 0.0001 |

| Enrichment-directeda | 22.37 | 0.0001 |

| Self-playing | 1.35 | 0.25 |

| Grooming | 1.28 | 0.27 |

| Social playing | 4.19 | 0.05 |

| Other affiliative behavior | 0.76 | 0.39 |

| Submissive behavior | 0.67 | 0.42 |

| Dominance or noncontact aggression | 0.72 | 0.40 |

| Contact aggression | 5.19 | 0.03 |

| Adult rhesus macaques | ||

| Abnormal, appetitivea | 23.12 | 0.0001 |

| Abnormal, locomotor | 4.3 | 0.05 |

| Noninjurious abnormala | 11.65 | 0.002 |

| Anxiety-related | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| Other self-directed behavior | 1.52 | 0.23 |

| Vigilancea | 21.26 | 0.0001 |

| Inactive | 3.06 | 0.09 |

| Locomotora | 12.59 | 0.001 |

| Foragingb | 8.68 | 0.006 |

| Eatinga | 24.26 | 0.0001 |

| Drinking | 2.17 | 0.15 |

| Enrichment-directed | 6.49 | 0.02 |

| Self-playing | 1.52 | 0.23 |

| Grooming | 7.07 | 0.02 |

| Social playing | 0.12 | 0.91 |

| Other affiliative behavior | 1.47 | 0.23 |

| Submissive behavior | 0.67 | 0.42 |

| Dominance or noncontact aggression | 1.36 | 0.25 |

| Contact aggression | 3.70 | 0.06 |

Differences (asignificant; bstatistical trend; factorial ANOVA) are indicated.

Figure 2.

Proportion (mean ± SE) of samples of behaviors significantly (*, P < 0.003; T [trend], 0.003 < P < 0.006) different between immature peer-reared and mother-reared rhesus macaques.

Adult subjects.

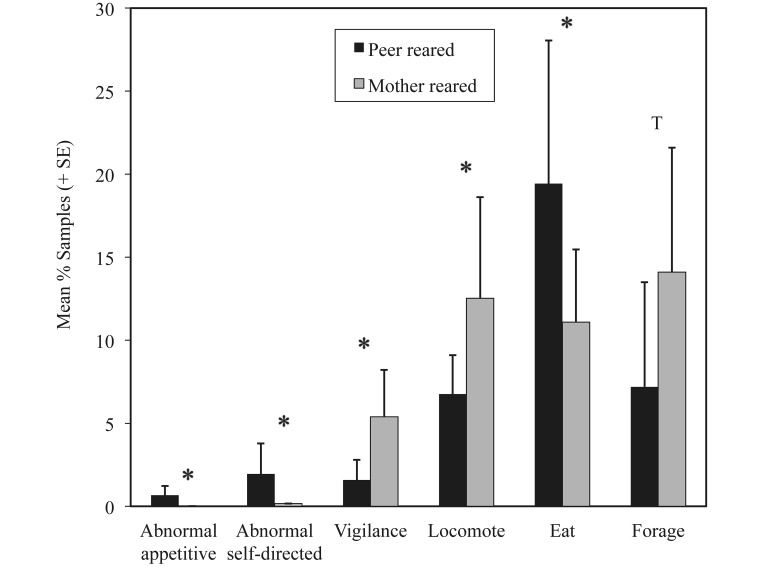

Multivariate ANOVA detected significant main effects of rearing (F18,15 = 6.13, P < 0.0001) but not sex (F18,15 = 2.34, P < 0.06) and showed significant interaction between sex and rearing (F18,15 = 3.96, P < 0.005), but no comparisons within individual behaviors reached statistical significance or the threshold for a trend. Significant main effects of rearing in adult macaques included differences in 5 behaviors and a trend toward a difference for an additional behavior (Table 1). Compared with their MR counterparts, PR adult macaques spent a significantly greater proportion of time engaged in appetitive abnormal behavior, noninjurious self-directed abnormal behavior, and eating but had lower levels of locomotion and vigilance and showed a trend toward lower levels of foraging (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proportion (mean ± SE) of samples of behaviors significantly (*, P < 0.003; T [trend], 0.003 < P < 0.006) different between adult peer-reared and mother-reared rhesus macaques.

Although too few data points were obtained for analyses, self-biting is an important concern regarding the management of captive macaques, and it is therefore appropriate to describe its occurrence during the current study. A single MR adult female subject was observed to self-bite on at least one occasion prior to the start of the study. Among the PR subjects, 4 female macaques (3 immature and one adult) and 2 immature male macaques were noted to self-bite on at least one occasion prior to the start of study. During the course of the study, 5 PR macaques were observed to self-bite at least once. No subject had a history of self-wounding, nor did any show marks or wounds on the skin consistent with self-wounding during the study period.

Discussion

In this study of outdoor group-housed rhesus macaques, rearing condition was associated with persistent effects on the expression of several abnormal behaviors and species–normative nonsocial behaviors. Rearing differences were manifest in both immature and adult subjects. However, to our surprise, rearing condition was not associated with any effects on the expression of social behavior.

In light of prior research findings on abnormal behavior, we expected that PR macaques would exhibit more abnormal behavior than would MR subjects, and the scoring methods we used prioritized capturing the expression of abnormal behaviors within both rearing groups. Compared with MR animals, PR macaques (as both immature animals and adults) engaged more often in most forms of abnormal behavior. Because the same abnormal behaviors remained increased among adult PR animals compared with MR macaques, the effects of peer rearing appear long lasting. Appetitive and noninjurious self- directed behaviors were elevated in both immature and adult PR subjects. Self-biting occurred rarely and only in PR macaques (note, however, that MR macaques in field cages at the center are not completely devoid of this behavior). Yet no differences in the levels of locomotor stereotypies (pacing being predominant) were found between MR and PR subjects in either age category. Although some prior research has revealed rearing effects on locomotor stereotypies,10,35 several other studies have failed to detect rearing effects on these behaviors under caged conditions.3,30 Our result regarding equivalent locomotor stereotypy levels in both rearing groups is particularly surprising in light of the fact that flooring differed between PR and MR subjects; substrates permitting foraging can reduce abnormal behavior.4,8 Compared with the concrete flooring on which the PR macaques were housed, the gravel ground cover in the run enclosures of the MR macaques might make foraging more time-consuming, such that lower levels of locomotor stereotypies would also be expected in MR subjects for this reason.

Also surprising was the absence of rearing effects on social behavior, which might have been expected in light of findings from other studies. Increased levels of fear and aggression are commonly attributed as effects of peer rearing.5,36 For example, PR rhesus monkeys have demonstrated inappropriate social behaviors, such as increased levels of aggression, compared with MR subjects.23 The current study detected no significant differences between affiliative or agonistic social behavior across age and rearing categories. However, the social groups were not manipulated or exposed to experimental stressors, which elicited an effect on social behaviors in the aforementioned studies.5,23,36 Similarly, peer rearing may lead to an increase in anxiety-related behaviors. One study found that, when compared with surrogate-PR and MR subjects, PR monkeys during the first 24 mo of life had elevated levels of anxious behavior along with increased hair cortisol levels after exposure to a stressor.13 Our results found an apparently transient trend toward increased anxiety-related behavior in the immature PR animals but, importantly, this difference was not found in the adult animals. This result is noteworthy in that it highlights the importance of studying adult macaques that experienced PR, because some rearing effects may wane with maturity.

The MR macaques demonstrated markedly higher levels of vigilance toward the macroenvironment, and this difference persisted into adulthood. These results may be related in part to differences in the quantity and type of observable human activity due to the locations of the enclosures within the center's breeding colony grounds. The PR subjects had the opportunity to become more acclimated to human activity, both because of being reared indoors initially and because the corncribs are adjacent to a building and wash area that the staff accessed daily. As such, much of the human activity that PR subjects could observe was not associated with their care. The run enclosures were surrounded by larger field cages; thus human activity around the MR animals more often led to activities within the subjects’ group or run complex. This difference in human exposure might also have contributed to the locomotor stereotypies observed in the MR subjects. It is important to reiterate here that levels of anxiety-related behavior did not differ between PR and MR groups, indicating that this reaction may be a marker of anticipation rather than distress. This finding suggests that when the variable of human exposure cannot be controlled, it may be helpful to record events that occur in the macroenvironment and incorporate them into the behavioral observations.

Our PR macaques locomoted less than did their MR counterparts, a finding that is consistent with previous work where decreased locomotion in nursery-reared macaques has been postulated to reflect the overall inhibition that these animals display compared with MR animals.6,11,40 In comparison, MR animals both locomoted more and were more inactive than the PR animals. However, level of inactivity may be an artifact of the higher levels of some abnormal behaviors in otherwise unoccupied PR animals. For example, a resting PR subject sucking on a digit was scored not as inactive but rather as behaving abnormally, whereas a resting MR animal would be scored as inactive in the absence of abnormal behavior. In a socially and physically restricted environment such as single housing in indoor caging, inactivity may derive from a lack of stimulation and opportunity for species-typical activities, and high levels of inactivity might be interpreted as a signal of poor wellbeing. Given the scoring methods that we used in the current study, the elevated levels of inactivity in immature MR subjects should not be interpreted as a signal of decreased wellbeing.

Despite the same feeding regimens for both groups, PR macaques demonstrated greater frequencies of eating and drinking. Elevated levels of eating (but not drinking) persisted into adulthood. Hyperphagia and polydipsia are described as being part of the ‘isolation syndrome’ that can affect infant rhesus macaques that are socially isolated after birth; these behaviors were found to continue well into adulthood in one group of rhesus macaques that was reared in this way.32 These behaviors also occur in human children in alternative-care programs.14,39,43 The relatively high levels of appetitive abnormal behaviors, such as coprophagy, urine drinking, and regurgitation with or without reingestion, in our PR macaques are consistent with an overall increase in consumption behavior, the function of which is unclear. However, one study revealed that, compared with MR counterparts, 2-y-old PR rhesus macaques increased preferred consumption of an aspartame solution over water and had an increased response to a startle test, demonstrating an overall enhanced response to stimuli.33 We are currently collecting measures on the possible effect of altered consummatory behavior on the growth and body condition of differentially reared macaques.

The results of the current study have practical implications for the management of rhesus macaques with different rearing backgrounds. First, PR macaques can be group-housed outdoors successfully without significant perturbation to social behavior. In addition, this particular population at our center has successfully been breeding and raising offspring, effectively replacing the derivation process.

Among the PR animals, differences such as elevated levels of enrichment-directed, anxiety-related, and drinking behaviors occurred in immature subjects but not in adults. The fact that immature PR macaques used enrichment more than did MR animals, coupled with the higher levels of abnormal behavior in the PR group, puts a premium on providing a highly enriched physical environment to PR animals. Enrichment-directed behavior dropped to low levels among adults of both rearing conditions. Several factors likely contribute to this finding among adults, such as a natural decrease in play behavior as macaques mature. Regarding the lack of a rearing effect on drinking that persisted into adulthood, the levels of the other appetitive behaviors remained significantly different between adult groups, such that it is unlikely that lower levels of drinking among PR adults reflect any overall rearing-associated decrease in consumption behavior in this population. In addition, the difference in anxiety-related behaviors was not found in the adult PR subjects. This finding suggests that rearing is not predictive of a lifetime tendency for increased anxiety and that maturity may assist in mitigating this behavior in PR rhesus macaques.

Adult macaques did not manifest any rearing effects that were not also seen in immature subjects. Differences were consistent with regard to abnormal behaviors, eating, locomoting, foraging, and vigilance. Therefore, managers should expect that rearing effects might not resolve spontaneously with age, and abnormal behaviors that develop may become lifelong issues. Conversely, these results also suggest that new behavioral differences may not surface over time in stable environments. With regard to choosing a rearing strategy, the absence of an effect on social behavior may be an important factor to consider in the decision-making process. Surrogate–peer rearing may appear particularly advantageous when macaques are destined for group housing, thus raising the relative importance of social competence. The fact that social behavior did not appear disrupted in our PR subjects suggests that, in the environment studied here, there is little tradeoff between problems with social and self-injurious behavior in these animals. However, self-injurious behavior was not entirely absent in either population: 5 PR macaques were observed to self-bite during the study period, but this behavior was recorded in no more than 0.1% of samples and was noted in only one adult subject. Peer rearing cannot be anticipated to prevent the development of this behavior altogether. Furthermore, self-injurious behavior has been observed in the MR population at the center, thus providing additional evidence that rearing history is only one of many factors contributing to the development of this behavior. Self-injurious behavior may not be apparent in a stable environment, such as the outdoor corncrib and run enclosures, but may appear in a different setting, such as indoor caging.

Although advances in knowledge regarding nursery rearing have led to paradigms enabling PR animals to live in social groups and reproduce successfully at levels similar to those of their MR counterparts, differences in behavior and physiology that continue into adulthood persist. Importantly, the peer-rearing paradigm at our institution appears to be equipped to generate animals that can live in complex social groups, perhaps more successfully than previous research might suggest. However, the current study followed only the like-reared groups in which expanded SPF animals are always maintained; perhaps difficulties with social dynamics might emerge in mixed rearing groups. For example, PR macaques tend to be low ranking within social groups containing MR conspecifics.2 In addition, we have not tested for rearing effects among indoor and singly housed macaque to know how these subjects might fare in such environments (in which some biomedical research subjects live).

Other limitations to the current study should be noted. On average, the group sizes for PR subjects were smaller than those of MR subjects. The relative levels of social behavior might have been influenced by group size, but there is no a priori reason to suspect that these differences in group size are of sufficient magnitude to mask rearing differences. In addition, the enclosure types differed between rearing groups and could have influenced some of the behavioral differences. We hope to address this possibility in the future, and we presently are collecting data from PR macaques housed in runs as well as from MR animals housed in corncribs. In addition, whether the difference in viral status (SPF and expanded SPF) influenced any of the results in the current study is unknown. This potential confound may already be controlled within the rearing style, given that immunologic functions are known to differ between PR and MR macaques.9,29

The current study contributes to the characterization of the long-term consequences of rearing background, helps to guide behavioral management decisions to meet the goals of macaque breeding programs, and may support the optimal psychologic wellbeing of research animals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) of the NIH through grants P51 OD011104, U42 OD010568, and U24 OD011109. No authors held conflicts of interest. All research complied with the USDA Animal Welfare Regulations. We thank the husbandry and behavioral management staff involved in the care of the macaques.

References

- 1.Animal Welfare Regulations. 2008. 9 CFR § 3.129.

- 2.Bastian ML, Sponberg AC, Suomi SJ, Higley JD. 2003. Long-term effects of infant rearing condition on the acquisition of dominance rank in juvenile and adult rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Dev Psychobiol 42:44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellanca RU, Crockett CM. 2002. Factors predicting increased incidence of abnormal behavior in male pigtailed macaques. Am J Primatol 58:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boccia ML, Hijazi AS. 1998. A foraging task reduces agonistic and stereotypic behaviors in pigtail macaque social groups. Lab Primate News 37:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunelli RL, Blake J, Willits N, Rommeck I, McCowan B. 2014. Effects of a mechanical response-contingent surrogate on the development of behaviors in nursery-reared rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 53:464–471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capitanio JP, Mason WA, Mendoza SP, DelRosso L, Roberts JA. 2006. Nursery rearing and biobehavioral organization, p 191–214. In: Sackett GP, Ruppenthal GC, Elias K. Nursery rearing of nonhuman primates in the 21st century. New York (NY): Springer Science and Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamove AS. 1973. Social behavior comparison in laboratory-reared stumptail and rhesus macaques. Folia Primatol (Basel) 19:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamove AS, Anderson JR, Morgan-Jones SC, Jones SP. 1982. Deep woodchip litter: hygiene, feeding, and behavioral enhancement in 8 primate species. Int J Study Anim Probl 3:308–318. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coe CL, Lubach GR, Schneider ML, Dierschke DJ, Ershler WB. 1992. Early rearing conditions alter immune responses in the developing infant primate. Pediatrics 90:505–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conti G, Hansman C, Heckman JJ, Novak MFX, Ruggier A, Suomi SJ. 2012. Primate evidence on the late health effects of early life adversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:8866–8871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corcoran CA, Pierre PJ, Haddad T, Bice C, Suomi SJ, Grant KA, Friedman DP, Bennett AJ. 2011. Long-term effects of differential early rearing in rhesus macaques: behavioral reactivity in adulthood. Dev Psychobiol 54:546–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cross HA, Harlow HF. 1965. Prolonged and progressive effects of partial isolation on the behavior of macaque monkeys. Journal of experimental research in personality 1:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dettmer AM, Novak MA, Suomi SJ, Meyer JS. 2012. Physiological and behavioral adaptation to relocation stress in differentially reared rhesus monkeys: hair cortisol as a biomarker for anxiety-related responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamond GW, Demb JM, Kaminer R, Soles B. 1987. Hyperphagia in foster care children. Pediatr Res 21:180A. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldfoot DA. 1977. Rearing conditions which support or inhibit later sexual potential of laboratory-born rhesus monkeys: hypotheses and diagnostic behaviours. Lab Anim Sci 27:548–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottlieb DH, Capitanio JP, McCowan B. 2013. Risk factors for stereotypic behavior and self-biting in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): animal's history, current environment, and personality. Am J Primatol 75:995–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goy RW, Wallen K, Goldfoot DA. 1974. Social factors affecting the development of mounting behavior in male rhesus monkeys. p 223–247. In: Montagna W, Sadler WA. Reproductive vehavior. New York (NY): Plenum Publishing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goy RW, Wallen K. 1979. Experiential variables influencing play, foot-clasp mounting, and adult sexual competence in male rhesus monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology 4:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harlow HF, Dodsworth RO, Harlow MK. 1965. Total social isolation in monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 54:90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow HF, Harlow MK. 1966. Learning to love. Am Sci 54:244–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higley JD, Hasert MF, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M. 1991. Nonhuman primate model of alcohol abuse: effects of early experience, personality, and stress on alcohol consumption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:7261–7265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higley JD, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M. 1991. CSF monoamine metabolite concentrations vary according to age, rearing, and sex, are influenced by the stressor of social separation in rhesus macaques. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 103:551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higley JD, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M. 1996. A nonhuman primate model of type II alcoholism? Part 2. Diminished social competence and excessive aggression correlates with low cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid concentrations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 20:643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackowski A, Perrara TD, Abdallah CG, Garrido G, Tang CY, Martinez J, Mathew SJ, Gorman JM, Rosenblum LA, Smith ELP, Dwork AJ, Shungu DC, Kaffman A, Gelernter J, Coplan JD, Kaufman J. 2011. Early-life stress, corpus callosum development, hippocampal volumetrics, and anxious behavior in male nonhuman primates. Psychiatry Res 192:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraemer GW, McKinney WT. 1979. Interactions of pharmacological agents which alter biogenic amine metabolism and depression: an analysis of contributing factors within a primate model of depression. J Affect Disord 1:33–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraemer GW. 1992. A psychobiological theory of attachment. Behav Brain Sci 15:493–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraemer GW, Clarke AS. 1996. Social attachment, brain function, and aggression. Ann N Y Acad Sci 794:121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubach GR, Coe CL, Ershler WB. 1995. Effects of early rearing environment on immune responses of infant rhesus monkeys. Brain Behav Immun 9:31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutz C, Well A, Novak M. 2003. Stereotypic and self-injurious behavior in rhesus macaques: a survey and retrospective analysis of environment and early experience. Am J Primatol 60:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutz CK, Davis EB, Ruggiero AM, Suomi SJ. 2007. Early predictors of self-biting in socially-housed rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Am J Primatol 69:584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller RE, Caul WF, Mirsky IA. 1971. Patterns of eating and drinking in socially isolated rhesus monkeys. Physiol Behav 7:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson EE, Herman KN, Barrett CE, Noble PL, Wojteczko K, Chisholm K, Delaney D, Ernst M, Fox NA, Suomi SJ, Winslow JT, Pine DS. 2009. Adverse rearing experiences enhance responding to both aversive and rewarding stimuli in juvenile rhesus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry 66:702–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novak MA, Sackett GP. 2006. The effects of rearing experiences: the early years, p 5–19. In: Sackett GP, Ruppenthal GC, Elias K. Nursery rearing of nonhuman primates in the 21st century. New York (NY):Springer Science+Business Media Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rommeck I, Anderson K, Heagerty A, Cameron A, McCowan B. 2009. Risk factors and remediation of self-injurious and self-abuse behavior in rhesus macaques. J Appl Anim Welf Sci 12:61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruppenthal GC, Walker CG, Sackett GP. 1991. Rearing infant monkeys (Macaca nemestrina) in pairs produces deficient social development compared with rearing in single cages. Am J Primatol 25:103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez MM, Hearn EF, Do D, Rilling JK, Herndon JG. 1998. Differential rearing affects corpus callosum size and cognitive function in rhesus monkeys. Brain Res 812:38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schapiro SJ, Lee-Parritz DE, Taylor LL, Watson L, Bloomsmith MA, Petto A. 1994. Behavioral management of specific pathogren-free rhesus macaques: group formation, reproduction, and parental competence. Lab Anim Sci 44:229–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simms MD, Dubowitz H, Szilagyi MA. 2000. Health care needs of children in the foster care system. Pediatrics 106:909–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spinelli S, Chefer S, Suomi SJ, Higley JD, Barr CS, Stein E. 2009. Early-life stress induces long-term morphologic changes in primate brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:658–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suomi SJ, Harlow HF, Kimball SD. 1971. Behavioral effects of prolonged partial social isolation in the rhesus monkey. Psychol Rep 29:1171–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suomi SJ. 1991. Early stress and adult emotional reactivity in rhesus monkeys. Ciba Found Symp 156:171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tarren-Sweeney M. 2006. Patterns of aberrant eating among preadolescent children in foster care. J Abnorm Child Psychol 34:623–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winslow JT, Noble PL, Lyons CK, Sterk SM, Insel TR. 2003. Rearing effects on cerebrospinal fluid oxytocin concentration and social buffering in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:910–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]