Abstract

This case report describes a rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta; male; age, 5 y; weight, 6.7 kg) with anorexia, dehydration, lethargy, ataxia, and generalized skin rashes that occurred 30 d after total-body irradiation at 6.5 Gy (60Co γ-rays). Physical examination revealed pale mucus membranes, a capillary refill time of 4 s, heart rate of 180 bpm. and respirations at 50 breaths per minute. Diffuse multifocal maculopapulovesicular rashes were present on the body, including mucocutaneous junctions. The CBC analysis revealed a Hct of 48%, RBC count of 6.2 × 106/µL, platelet count of 44 × 103/µL, and WBC count of 25 × 103/µL of WBC. The macaque was euthanized in light of a grave prognosis. Gross examination revealed white foci on the liver, multifocal generalized petechiation on serosal and mucosal surfaces of the gastrointestinal tract, hemorrhagic lymph nodes, and hemorrhagic fluid in the thoracic cavity. Microscopic examination revealed cutaneous vesicular lesions with intranuclear eosinophilic viral inclusions within the epithelial cells, consistent with herpesvirus. Immunohistochemistry was positive for herpesvirus. The serum sample was negative for antibodies against Macacine herpesvirus 1 and Cercopithecine herpesvirus 9 (simian varicella virus, SVV). Samples submitted for PCR-based identification of the etiologic agent confirmed the presence of SVV DNA. PCR analysis, immunohistochemistry, and histology confirmed that lesions were attributed to an active SVV infection in this macaque. This case illustrates the importance of screening for SVV in rhesus macaques, especially those used in studies that involve immunosuppressive procedures.

Abbreviations: SVV, simian varicella virus; TBI, total-body irradiation

Case Report

This 5-y-old, male rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) was involved in an IACUC-approved radiation countermeasure study. The macaque was housed in an AAALAC-accredited animal facility (Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute, Bethesda, MD), was fed a commercial diet (T2050, Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN), and had unrestricted access to water. He was serologically negative for Macacine herpesvirus 1 (B virus), simian retrovirus, simian T-cell leukemia virus, and SIV. He was vaccinated against measles virus and had confirmed positive antibody titers.

As mandated by the study protocol, this macaque received bilateral total-body irradiation (TBI) to 6.5 Gy with 60Co γ-rays at a dose rate of 0.6 Gy/min. At 24 h prior to TBI, he received a radiation countermeasure test article through midscapular subcutaneous injection (2 mL). TBI causes suppression of the bone marrow, which leads to marked reductions in RBC, platelet, and WBC counts. Pancytopenia occurred around 10 to 17 d after TBI. Recovery of bone marrow, RBC, WBC, and platelet counts began on or about day 21. Around day 31 after TBI, during the recovery phase, this macaque presented with reduced appetite, difficulty in breathing, lethargy, ataxia, and a generalized skin rash.

Physical examination under sedation (ketamine hydrochloride, 40 mg IM) revealed pale mucus membranes, capillary refill time of 4 s, heart rate of 180 bpm, and respiratory rate of 50 breaths per minute. Multifocal maculopapulovesicular rashes were diffusely present on the body, including mucocutaneous junctions (Figure 1). The CBC analysis (Advia 120, Bayer, Tarrytown, NY) indicated a Hct of 48%, RBC count of 6.2 × 106/µL, platelet count of 44 × 103/µL, and WBC count of 25 × 103/µL.

Figure 1.

Multifocal maculopapulovesicular rashes on the skin of the (A) face, (B) abdomen, and (C) hindlegs. (D) Maculopapulovesicular rash.

Differential diagnoses included TBI, opportunistic bacterial skin infection, herpes B viral recrudescence, simian varicella virus (SVV; monkey chicken pox, Cercopithecine herpesvirus 9), monkeypox, and measles virus. Measles was lowest on the differential list and was considered unlikely due to the vaccination status of this animal. TBI can cause skin lesions, such as petechiation, due to thrombocytopenia.2,4

The macaque was euthanized. The room in which this animal was housed was placed under quarantine to prevent the spread of disease. Necropsy was performed, and a complete set of tissues was collected for microscopic evaluation.

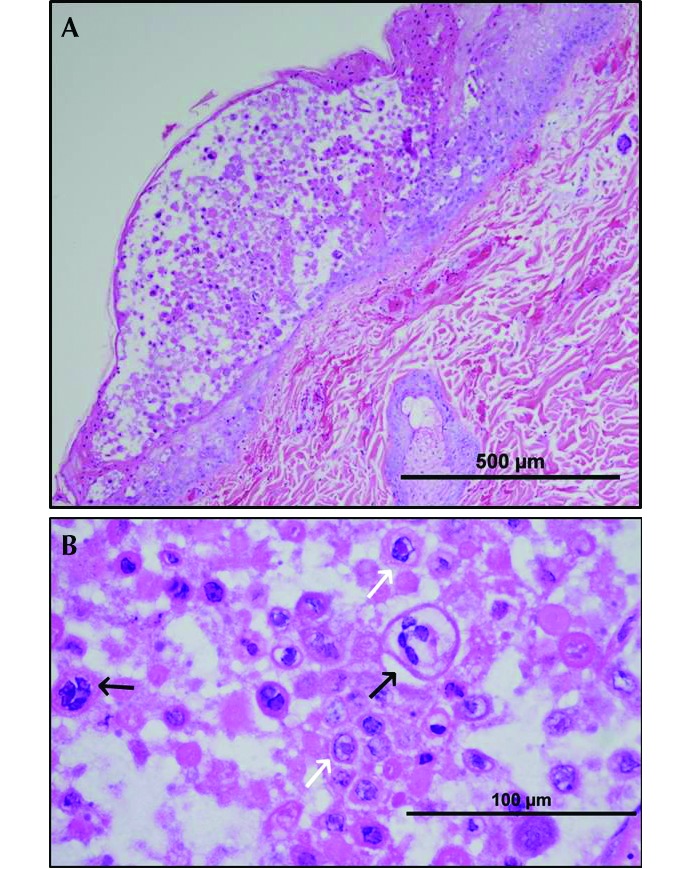

Gross examination revealed multifocal generalized petechiation on serosal and mucosal surfaces of the gastrointestinal tract, hemorrhagic lymph nodes, and approximately 10 mL of hemorrhagic fluid in the thoracic cavity. These findings are consistent with TBI exposure. In addition, the liver contained multifocal, minute, white foci (Figure 2). Microscopic examination revealed vesicular lesions on the skin, with intranuclear eosinophilic viral inclusions within the epithelial cells, and numerous epithelial syncytia (Figure 3). Bone marrow progenitor cells were necrotic, with intranuclear inclusions. The lung demonstrated necrosis with hemorrhage, fibrin, and edema, and alveolar macrophages frequently contained eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions. The liver had multifocal, random areas of necrosis (correlating with the white foci observed grossly) and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions within hepatocytes. Gastric mucosal hemorrhage and necrosis and gastric crypt necrosis with eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions within crypt epithelial cells were present.

Figure 2.

Multifocal, minute, white foci (white arrows) within the liver.

Figure 3.

(A) Haired skin: degeneration and necrosis with vesicle formation. (B) Haired skin (higher magnification): necrotic epithelial cells, epithelial syncytia (black arrows), and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions (white arrows). Hematoxylin and eosin stain.

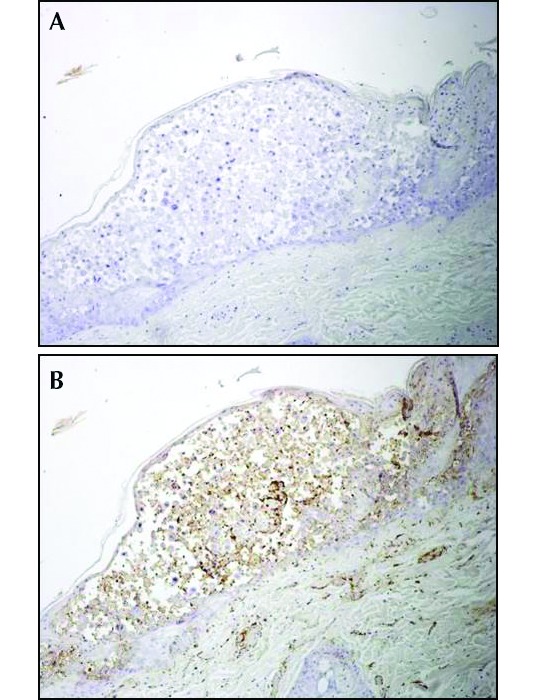

The presence of eosinophilic inclusions in multiple organs and epithelial syncytia is consistent with herpesvirus etiology. Immunohistochemistry performed at the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases confirmed herpesvirus etiology. The skin lesions were diffusely, strongly immunoreactive for herpesvirus antigen and negative for monkeypox antigen (Figure 4). A serum sample was submitted to classify the etiologic agent (BioReliance, Rockville, MD). The serum sample was negative for antibodies against Macacine herpesvirus 1 (herpes B virus) and Cercopithecine herpesvirus 9 (SVV). An EDTA-treated whole-blood sample and a skin swab from the lesions were submitted for PCR-based identification of the etiologic agent (Zoologix, Chatsworth, CA). The PCR assay confirmed the presence of SVV DNA; the samples were negative for herpes B virus DNA. PCR assays, immunohistochemistry, and histology analysis confirmed that the lesions were due to an active SVV infection in this macaque.

Figure 4.

(A) Skin vesicle immunohistochemically negative for monkey poxvirus and (B) diffuse, strong positive immunoreactivity for herpesvirus antigen.

The entire inhouse colony of rhesus macaques underwent serologic analysis for SVV. Of the 77 animals tested, 27 (35%) were seropositive, 47 (61%) were seronegative, and 3 (4%) were not tested because of unavailability of samples. In the period from 2012 to 2014, 57 (74%) macaques were involved in radiation countermeasures and dosimetry studies. These animals received TBI exposure at a broad dose range of 1.0 to 8.5 Gy. Of these 57 macaques, only 2 have developed clinical signs of SVV, which was confirmed by histopathology and PCR analysis. One of these 2 macaques is the subject of the current case report and was seronegative. The other animal was irradiated at 7 Gy and, on day 38 after TBI, developed clinical signs similar to those of the macaque we present here. Serological status of this animal could not be tested due to unavailability of sample.

Discussion

Cercopithecine herpesvirus 9 (SVV) is a member of Alphaherpesvirinae in the genus Varicellovirus. This virus causes highly contagious disease that can result in significant morbidity and mortality in numerous Old World NHP. SVV has a high degree of antigenic similarity to human varicella–zoster virus, the etiologic agent of chickenpox. SVV spreads rapidly by the respiratory route and through direct contact with skin lesions. SVV is not considered a zoonotic virus, and there is no known treatment. Acyclovir and interferon have shown some potential in experimental infections.1,3

Acute radiation syndrome occurs after whole-body or significant partial-body exposure to ionizing radiation. Clinical components of acute radiation syndrome include the hematopoietic, gastrointestinal, and cerebrovascular subsyndromes.4 In the hematopoietic subsyndrome, the numbers of RBC, WBC, and platelets decline, and susceptibility to potentially fatal infection increases. In the gastrointestinal subsyndrome, the breakdown of the gastrointestinal system results in the translocation of gastrointestinal bacteria to other organs, ultimately resulting in sepsis and eventually death. Collectively, hematopoietic subsyndrome and gastrointestinal subsyndrome are well recognized as the major subsyndromes of the acute radiation syndrome. However, these subsyndromes tend to oversimplify the clinical reality of acute radiation syndrome, because it often involves complex, multiorgan dysfunctions.2,6,10 Lymphocytes, the cells most sensitive to radiation injury, are the first cellular population to disappear from the circulation after exposure to radiation. Lymphocyte loss is followed by neutrophil loss and then platelet loss over the course of several days. Injury to the immune and hematopoietic systems may cause death due to impaired immunity, leading to subsequent infections, or fatal hemorrhages, as a result of thrombocytopenia.

At our facility, there were 2 cases of SVV in rhesus macaques at 30 to 38 d after TBI (6.5 to 7.0 Gy). SVV has previously been reported in macaques under stress conditions, such as TBI, old age, and shipment. Previous cases of SVV have involved a rhesus macaque8 (105 d after TBI to 6 Gy) and pigtailed macaque7 (11 to 15 mo after TBI). Cases of SVV have occurred in aged (20 to 22 y) rhesus macaques.5,11 Transportation-stress–related SVV infection affected 12 of 165 rhesus macaques at 6 d after their overseas shipment.9

During 2012 to 2014 at our institution, 57 rhesus macaques received TBI at a dose range of 1.0 to 8.5 Gy. There were only 2 confirmed cases of SVV after TBI on the basis of the clinical signs, histopathology, and PCR analysis. We did not pursue why the disease was triggered after TBI in only some (not all) irradiated macaques. We speculate that multiple factors are involved, including the recrudescence of latent infection under stressful conditions, new infection acquired from a cohoused animal shedding the virus, and the serologic status of the animal. This case illustrates the importance of screening rhesus macaques for SVV, especially those in studies leading to immunosuppression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian L Johnson, Janeen Lewis, Todd Bell, and Chris Mech for technical contributions. This research was funded by the Defense Medical Research Development Program, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-Inter Agency Agreement Contract, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and Defense Threat Reduction Agency. The opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied do not necessarily reflect the view of the Department of Defense or any other department or agency of the United States federal government.

References

- 1.Abee C, Mansfield K, Tardiff S, Morris T. 2012. Nonhuman primates in biomedical research: diseases, vol. 2. San Diego (CA): Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fliedner TM, Dorr HD, Meineke V. 2005. Multiorgan involvement as a pathogenetic principle of the radiation syndromes: a study involving 110 case histories documented in SEARCH and classified as the bases of haematopoietic indicators of effect. Br J Radiol Suppl 27:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox JG, Anderson LC, Loew FM, Quimby FW. 2002. Laboratory animal medicine, 2nd ed. San Diego (CA): Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ. 2012. Radiobiology for the radiobiologist. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halliday LC, Fortman JD. 2011. Severe thrombocytopenia in aged rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) infected with simian varicella virus. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 50:109–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill RP. 2005. Radiation effects on the respiratory system. Br J Radiol Suppl 27:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hukkanen RR, Gillen M, Grant R, Liggitt HD, Kiem HP, Kelley ST. 2009. Simian varicella virus in pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina): clinical, pathologic, and virologic features. Comp Med 59:482–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolappaswamy K, Mahalingam R, Traina-Dorge V, Shipley ST, Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-Demasters BK, McLeod CG, Jr, Hungerford LL, DeTolla LJ. 2007. Disseminated simian varicella virus infection in an irradiated rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). J Virol 81:411–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millen L, Tomanek L, Gonzalez-Arroyo S, Zao CL. 2014. Cercopithecine herpesvirus 9 (simian varicella virus) infection in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Abstracts presented at the Association of Primate Veterinarians 42nd workshop, San Antonio, TX, 15–18 October 2014.J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 54:96 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moulder JE, Cohen EP. 2005. Radiation-induced multiorgan involvement and failure: the contribution of radiation effects on the renal system. Br J Radiol Suppl 27:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoeb TR, Eberle R, Black DH, Parker RF, Cartner SC. 2008. Diagnostic exercise: papulovesicular dermatitis in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol 45:592–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]