Abstract

Goals of this study were to examine the mental health processes whereby everyday discrimination is associated with physical health outcomes. Data are drawn from a community health survey conducted with 1299 US adults in a low-resource urban area. Frequency of everyday discrimination was associated with overall self-rated health, use of the emergency department, and one or more chronic diseases via stress and depressive symptoms operating in serial mediation. Associations were consistent across members of different racial/ethnic groups and were observed even after controlling for indicators of stressors associated with structural discrimination, including perceived neighborhood unsafety, food insecurity, and financial stress.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, everyday discrimination, health, stress, structural discrimination

Introduction

Discrimination adversely affects health (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009; Williams and Mohammed, 2008). Results from cross-sectional, longitudinal, and experimental studies demonstrate that discrimination is associated with a wide range of poor physical and mental health outcomes (Williams and Mohammed, 2008). Discrimination is associated with worse overall self-rated health (Harris et al., 2006; Schulz et al., 2006) and higher risk of chronic disease incidence (e.g. respiratory, cardiovascular, and pain conditions; Gee et al., 2007). It is also associated with specific diseases (e.g. cardiovascular and respiratory conditions; Gee et al., 2007) and behaviors (e.g. substance use, violence; Borrell et al., 2007; Romero et al., 2007; Simmons et al., 2006) that increase risk of urgent health problems requiring emergency department visits (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). Moreover, discrimination is associated with depressive symptoms (Banks et al., 2006; Brody et al., 2006; Steffen and Bowden, 2006) and stress (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009). Everyday discrimination—involving chronic yet subtle mistreatment due to a socially devalued characteristic (e.g. race, weight, low income)—is pervasive and theorized to play a powerful role in creating and maintaining the substantial health disparities observed in the United States (Essed, 1991; Williams et al., 2003; Williams and Mohammed, 2008).

Despite the wealth of evidence demonstrating harmful associations between discrimination and health, significant gaps in understanding of these associations have been highlighted. Williams and Mohammed (2008) emphasize the importance of understanding the processes whereby discrimination relates to physical health, which may provide insight into how to intervene. We examined the mental health processes through which everyday discrimination is associated with indicators of general, emergency, and chronic health among a sample of mostly Black residents of a low-income urban area in the United States.

The mediating roles of stress and depressive symptoms

Stress and depressive symptoms appear to play important roles in the process whereby everyday discrimination is associated with physical health. Experimental studies demonstrate that experiences of discrimination elicit both physiological (e.g. cardiovascular reactivity) and psychological (e.g. perceived stress) stress responses (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009). Stress responses, in turn, impact a range of chronic and acute physical health conditions (Pearlin et al., 2005; Williams et al., 1997, 2003; Williams and Mohammed, 2008).

Everyday discrimination is also associated with depression and depressive symptoms (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009; Williams et al., 2003). Carter’s model of Race-Based Traumatic Stress Injury suggests that accumulated experiences of stress resulting from discrimination may lead to greater depressive symptoms over time (Carter, 2007). Longitudinal evidence demonstrates that people who experience stress subsequently experience greater depressive symptoms (Kessler, 1997). Depressive symptoms, in turn, are associated with poor physical health in part via changes in physiological (e.g. cellular immunity; Herbert and Cohen, 1993) and behavioral (e.g. physical activity; Ruo et al., 2003; Whooley et al., 2008) activity.

This study

We hypothesize that greater frequency of everyday discrimination is associated with greater stress, which in turn is associated with greater depressive symptoms, and which in turn are associated with worse physical health. That is, we expect a serial mediation model linking everyday discrimination with poorer physical health outcomes, including indicators of general, emergency, and chronic health.

Williams and Mohammed (2008) note that experiences of everyday discrimination at the individual level are merely one way in which discrimination generates stress and poor health. At the structural level, residential segregation, a legacy of institutionalized discrimination in residential contexts, exposes individuals to ongoing violence and results in chronic safety concerns (Williams and Collins, 2001; Williams and Mohammed, 2008). Economic hardship, a lasting effect of institutionalized discrimination in employment contexts, further leads to financial stress and food insecurity. We control for perceived neighborhood unsafety, food insecurity, and financial stress in all analyses to better understand the unique contribution of everyday discrimination to poor health outcomes amidst these stressors associated with structural discrimination.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Health and behavior surveys were conducted with adults aged 18–65 years living in six low-income neighborhoods in New Haven, Connecticut, in the fall of 2012. Households were randomized from a complete list of addresses provided by the City of New Haven. Randomly selected addresses were approached three times until (1) an eligible resident answered and consented to be surveyed, (2) an eligible resident answered and refused, or (3) no one answered. If the survey was not conducted, another address was selected and approached. Surveys were administered by locally hired and trained residents, lasted 20–30 minutes, and were collected via handheld computers. Participants received a US$10 grocery gift card and entry into a US$500 raffle. Participants included 1299 adults (73% response rate) who were older and more likely to be women and Black than neighborhood residents as a whole. During the time of data collection, structural interventions designed to improve community health were being implemented in several neighborhoods. All procedures received ethics approval.

Measures

Participants answered questions about socio-demographic and other characteristics related to health and behavior.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Participants were asked to identify their gender with response options including male, female, and transgender. Only four participants identified as transgender, and they were marked as “missing” for this variable. Participants were asked to identify their race/ethnicity with response options including White, Black, Hispanic/ Latino, Asian, American Indian/ Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander, Multi-racial, and Other. All participants who identified as Hispanic/Latino were coded as Latino(a) or Hispanic American; all non-Latino participants who identified as Black were coded as Black or African American; and all other participants were coded as White or Other. Participants were asked to list their age. Participants were asked whether they were born in the United States with response options including yes and no. Participants were asked their highest level of completed education with response options including no formal schooling, grade school completed, some secondary school, high school/General Educational Development (GED) completed, some college or associate’s degree completed, bachelor’s completed, and some or completed post-graduate degree. These responses were categorized into Less than High School Degree, High School/GED Completed, and Some College or More. Participants reported their height and weight, which were used to calculate categories of body mass index (BMI). Participants were asked whether they had health insurance with response options including Yes, I have health insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid; No, I do not have it now, but I used to have health insurance; or I have never had health insurance. For this study, participants were categorized as either currently or not currently having health insurance.

Health outcomes

Overall health was measured with the validated item “How would you rate your overall health?”, rated on a 5-point scale from poor to excellent (Pleis et al., 2010). Participants were asked the number of times in the past year they visited a hospital emergency department. Answers were dichotomized to reflect zero emergency department visits (57.3%) or one or more visits (42.7%) (Long et al., 2012). Participants were also asked to indicate whether they had ever been told by a doctor or health professional that they had the following chronic conditions: high cholesterol, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, asthma, chronic bronchitis or emphysema, or cancer (Pleis et al., 2010). Answers were dichotomized to reflect zero chronic conditions (57.4%) versus one or more conditions (42.6%) (National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Description, 2012).

Everyday discrimination

Everyday discrimination was measured using the 5-item Everyday Discrimination Scale (Stucky et al., 2011). Participants were asked how frequently they were treated with less respect than others, treated as not smart, treated as dishonest, treated as if others were better than them, and insulted or called names on 5-point scale from never to very often. Items were averaged and demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

Stress and depressive symptoms

Stress was measured using Cohen’s 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983; Cohen and Williamson, 1988). Participants were asked how often, on a 5-point scale from never to very often, they were unable to control important things in their life, felt confident about their ability to handle personal problems (reverse-scored), felt that things were going their way (reverse-scored), and felt difficulties piling up so high that they could not overcome them. Items were averaged (Cronbach’s α=0.60). Depressive symptoms were measured using two items from the Patient Health Questionnaire (Li et al., 2007), adapted to ask about the past 30 days. Participants were asked how often they felt bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless and by little interest or pleasure in doing things on a 4-point scale from not at all to nearly every day. Items were averaged (Cronbach’s α=0.80).

Other stressors

Perceived unsafety was measured with the item “I feel unsafe to go on walks in my neighborhood during the day,” rated on a 5-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree (Bauman et al., 2009). Food insecurity was measured with two items, which asked whether members of participants’ households worried whether their food would run out before they got money to buy food and whether the food they bought did not last and they did not have money to get more in the past 12 months (Hager et al., 2010). Participants indicated responses on a 3-point scale from often true to never true. Items were reverse-coded such that higher scores reflected greater food insecurity and then averaged (α=0.89). To measure financial stress, participants were asked how well they were managing financially these days (Weich and Lewis, 1998). Response options were on a 5-point scale including living comfortably, doing alright, just getting by, finding it difficult, and very difficult.

Survey order

Items and scales used in this study were embedded within a larger survey including a total of 176 items. Items appeared in the following order within the survey: perceived unsafety, everyday discrimination, overall health, chronic health conditions, health insurance, emergency department visits, weight and height for BMI, depressive symptoms, stress, food insecurity, gender, age, race/ethnicity, nativity, education, and financial stress.

Analyses

First, participant socio-demographic characteristics and other stressors were characterized using descriptive statistics. Differences in frequency of everyday discrimination scores by socio-demographic characteristics and other stressors were explored using analyses of variance with Bonferroni post hoc tests and correlations. Second, we tested whether stress and depressive symptoms operating in serial mediated associations between everyday discrimination and health outcomes while adjusting for other stressors (perceived unsafety, food insecurity, and financial stress) and socio-demographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity, age, place of birth, education, BMI, health insurance) using path analysis. Analyses also controlled for whether participants lived in neighborhoods implementing the structural intervention to improve community health (referred to as study condition). We used bootstrapping to estimate the indirect effects of everyday discrimination on health outcomes via stress and depressive symptoms. A post hoc power analysis indicated that we were adequately powered to conduct this analysis (power = 1.00; Gnabs, 2008; MacCallum et al., 1996).

Results

The majority of participants identified as female, Black or African American, and US born (Table 1). The average age of participants was 40 years. Close to half of participants reported achieving at least some college. Over one-half of participants were overweight or obese based on self-reported weight and height. The majority of participants reported having health insurance.

Table 1.

Participant socio-demographic characteristics and other stressors (N =1299).

| % (n) or M (SD) | Everyday discrimination | |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||

| Gender | F(1, 1286)=3.41, p =0.07 | |

| Female | 64.0 (832) | 1.62 (0.72) |

| Male | 35.3 (458) | 1.70 (0.78) |

| Race/ethnicity | F(2, 1282)=3.25, p =0.04 | |

| Black or African American | 62.0 (805) | 1.61 (0.72) |

| Latino(a) or Hispanic American | 17.5 (227) | 1.70 (0.74) |

| White or Other | 19.7 (256) | 1.73 (0.82) |

| Age | 40.60 (13.37) | r = −0.07, p =0.02 |

| Nativity | F(1, 1290)=0.23, p =0.64 | |

| US born | 90.8 (1179) | 1.65 (0.74) |

| Other | 8.9 (115) | 1.62 (0.78) |

| Education | F(2, 1276)=7.37, p =0.001 | |

| Less than high school | 14.3 (186) | 1.82 (0.91)a,b |

| High school/GED completed | 36.5 (474) | 1.64 (0.70)a |

| Some college or more | 47.7 (620) | 1.59 (0.68)b |

| BMI categories | F(3, 1134)=0.45, p =0.72 | |

| Underweight | 3.9 (51) | 1.65 (0.78) |

| Healthy weight | 23.3 (303) | 1.68 (0.73) |

| Overweight | 22.9 (297) | 1.61 (0.75) |

| Obese | 37.4 (486) | 1.63 (0.73) |

| Health Insurance | F(1, 1286)=0.55, p =0.02 | |

| Insured | 87.1 (1132) | 1.63 (0.72)a |

| Not insured | 11.9 (155) | 1.78 (0.89)a |

| Other stressors | ||

| Perceived unsafety | 2.00 (1.06) | r = 0.12, p <.001 |

| Food insecurity | 1.53 (0.65) | r = 0.24, p <.001 |

| Financial stress | 2.57 (1.08) | r = 0.20, p <.001 |

| Total | 1.65 (0.74) | |

SD: standard deviation; GED: General Educational Development; BMI: body mass index.

Values that share a super-script (a and/or b) are statistically significantly different, p < 0.05. Percentages may not add to 100 due to missing data. Everyday discrimination, perceived unsafety, and financial stress ranged from 1 to 5 and food insecurity from 1 to 3.

On average, participants reported that they experienced everyday discrimination infrequently (mean (M)=1.65, standard deviation (SD) = 0.74). Average scores on the everyday discrimination scale were generally similar across participants, with some statistically significant differences. As shown in Table 1, participants who reported less than a high school education reported more frequent discrimination than participants with a college education. Participants with no health insurance reported more frequent discrimination than participants with health insurance. Younger participants reported more frequent discrimination than older participants. There was a trend for Black or African American participants to report less discrimination than Latino(a) or Hispanic American and White or Other participants, but these differences were not statistically significant in post hoc tests. Participants who reported more perceived unsafety, food insecurity, and financial stress also reported more frequent discrimination.

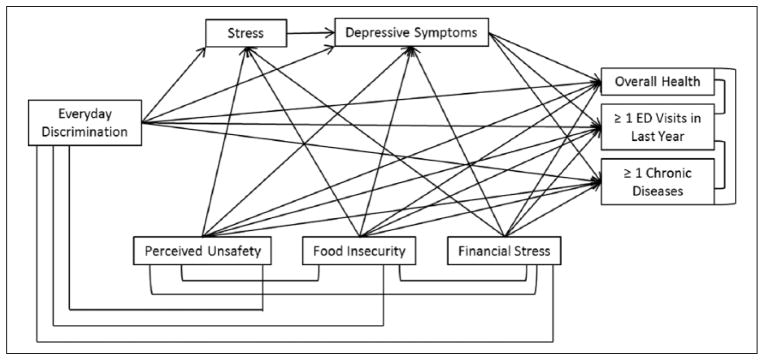

We first evaluated a path model including paths from frequency of everyday discrimination to all mediators and outcomes, from all mediators to all outcomes, and all other stressors to all mediators and outcomes (Figure 1). We included paths from all socio-demographic characteristics to all mediators and health outcomes. We further included correlated errors between everyday discrimination and other stressors, and between all health outcomes. Model fit indices demonstrated adequate fit for the data: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.05, confidence interval (CI) = 0.04–0.06; Comparative Fit Index (CFI)=0.93; χ2(36)=126.04, p<0.001. Many of the socio-demographic paths were non-significant, which tends to diminish the overall model fit. To determine model fit without the inclusion of these paths, we trimmed the socio-demographic characteristics as well as their paths to all mediators and health outcomes and re-tested the model. This yielded a fully saturated model, which provides no information regarding model fit. Stress was not directly associated with any of the health outcomes; we therefore trimmed paths from stress to outcomes to acquire model fit statistics. The general pattern of results (i.e. significance and direction of effects of paths) remained the same as the original model. This yielded a model that was a strong fit for the data: RMSEA = 0.00, CI = 0.00–0.05; CFI=1.00; χ2(3)=2.64, p=0.45. Given that results were consistent between the two models, we present statistics from the model adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics.

Figure 1.

Path model linking frequency of everyday discrimination with health outcomes via stress and depressive symptoms operating in serial mediation.

Controlling for the effects of socio-demographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity, age, place of birth, education, body mass index (BMI), health insurance) on stress, depressive symptoms, overall health, emergency department (ED) visits, and chronic diseases.

Path model results suggested that participants who reported more frequent everyday discrimination also reported greater stress and depressive symptoms (Table 2). Furthermore, participants who reported greater stress also reported greater depressive symptoms. In turn, participants who reported greater depressive symptoms reported worse overall self-rated health, greater likelihood of having one or more emergency department visits in the past year, and greater likelihood of having been diagnosed with one or more chronic diseases. All three indicators of physical health were correlated, suggesting that participants reporting better overall self-health were less likely to have one or more emergency room visits (r=−0.17, p < 0.001) and one or more chronic diseases (r=−0.25, p<0.001). Additionally, participants who had one or more emergency department visits were more likely to have one more chronic diseases (r=0.26, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Path model results, including unstandardized path coefficients.

| Paths | Stress

|

Depressive symptoms

|

Overall self-rated health

|

≥1 ED visits in last year

|

≥1 Chronic diseases

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | |

| Everyday discrimination | 0.22 (0.03) | <.001 | 0.07 (0.02) | <.001 | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.65 | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.03 | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.04 |

| Mediators | ||||||||||

| Stress | 0.40 (0.02) | <.001 | −0.09 (0.05) | 0.04 | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.73 | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.37 | ||

| Depressive symptoms | −0.12 (0.04) | 0.01 | 0.25 (0.05) | <.001 | 0.16 (0.06) | 0.01 | ||||

| Other stressors | ||||||||||

| Perceived unsafety | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.03 | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.68 | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.76 | −0.04 (0.04) | 0.35 | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.73 |

| Food insecurity | 0.19 (0.04) | <.001 | 0.15 (0.03) | <.001 | −0.02 (0.06) | 0.75 | 0.15 (0.07) | 0.03 | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.07 |

| Financial stress | 0.19 (0.04) | <.001 | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.41 | −0.10 (0.03) | 0.01 | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.25 | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.43 |

| Socio-demographic controls | ||||||||||

| Male | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.95 | −0.05 (0.04) | 0.26 | 0.21 (0.07) | 0.01 | −0.15 (0.08) | 0.07 | −0.13 (0.08) | 0.11 |

| Black | −0.09 (0.07) | 0.17 | −0.17 (0.05) | <.001 | −0.05 (0.08) | 0.58 | 0.06 (0.10) | 0.58 | −0.22 (0.10) | 0.03 |

| Latino | 0.02 (0.08) | 0.81 | −0.02 (0.06) | 0.72 | −0.20 (0.11) | 0.07 | 0.12 (0.13) | 0.34 | −0.05 (0.13) | 0.71 |

| Age | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.41 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.10 | −0.01 (0.01) | <.001 | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 | 0.02 (0.01) | <.001 |

| Born outside the | −0.01 (0.10) | 0.98 | 0.15 (0.07) | 0.03 | 0.10 (0.12) | 0.42 | −0.51 (0.15) | 0.01 | −0.37 (0.15) | 0.02 |

| United States | ||||||||||

| College education | −0.18 (0.05) | <.001 | −0.04 (0.04) | 0.32 | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.62 | −0.10 (0.08) | 0.19 | −0.11 (0.08) | 0.16 |

| BMI | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.31 | 0.01 (0.01) | <.001 | −0.03 (0.01) | <.001 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.96 | 0.02 (0.01) | <.001 |

| No health insurance | 0.20 (0.08) | 0.01 | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.03 | −0.15 (0.10) | 0.16 | −0.07 (0.12) | 0.56 | −0.04 (0.13) | 0.74 |

| Study condition | −0.02 (0.05) | 0.65 | −0.05 (0.04) | 0.24 | −0.04 (0.07) | 0.51 | −0.09 (0.08) | 0.28 | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.65 |

| Variance explained | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p |

| 0.22 | <.001 | 0.32 | <.001 | 0.14 | <.001 | 0.13 | <.001 | 0.19 | <.001 | |

ED: emergency department; SE: standard error; BMI: body mass index.

Results of the bootstrapping analyses indicated an indirect effect of everyday discrimination on depressive symptoms via stress (B (SE) = 0.09 (0.01), p < 0.001). There were also indirect effects of everyday discrimination on all health outcomes via stress and depressive symptoms operating in serial mediation, including overall health (B (SE) = −0.02 (0.01), p = 0.01), more than one visit to the emergency department in the past year (B (SE) = 0.02 (0.01), p = 0.01), and more than one chronic disease (B (SE) = 0.02 (0.01), p = 0.01).

We conducted several post hoc tests. We first tested a reverse model, including depressive symptoms predicting stress and everyday discrimination operating in serial mediation. This yielded a model that was a poor fit for the data: RMSEA=0.15, CI=0.14–0.16; CFI=0.70; χ2(15)= 431.57, p < 0.01. We further conducted a multi-group analysis to determine whether the model fit varied by participant race/ethnicity (Black, Latino, Other). We conducted a test of chi-square invariance by setting paths to be equal and then performed a chi-square difference test. This was nonsignificant; χ2(58)=70.061, p=0.13; which suggests that the model was invariant across racial/ethnic groups. We therefore did not find evidence of moderation of the model by participant race/ethnicity.

Discussion

This study draws on data collected from predominantly Black residents of a low-income urban area to elucidate the process whereby everyday discrimination is associated with poor health outcomes. Consistent with Carter’s model of Race-Based Traumatic Stress Injury (Carter, 2007), results suggest that more frequent experiences of everyday discrimination are associated with greater stress, which in turn is associated with greater depressive symptoms, which are associated with poor health outcomes. This pattern was consistent for all three tested health outcomes, including indicators of general, emergency, and chronic health. Furthermore, associations between everyday discrimination and health were consistent across racial/ethnic groups and were statistically significant even after controlling for other stressors related to social disadvantage including perceived unsafety, food insecurity, and financial stress.

Limitations and future directions

This study employs cross-sectional methodology, limiting our ability to form causal conclusions regarding the theorized process. Future research should study associations between everyday discrimination, stress, depressive symptoms, and health outcomes using longitudinal and experimental methodology. Ecological momentary assessment, an intensive form of longitudinal methodology (Stone and Shiffman, 1994), may be particularly useful for disentangling the shorter and longer term effects of everyday discrimination on health and has been useful in assessing racism specifically (Brondolo et al., 2008; Broudy et al., 2007). Given that past longitudinal and experimental studies provide evidence for many of the individual paths in the model (Kessler, 1997; Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009; Pearlin et al., 2005; Whooley et al., 2008), we expect that future longitudinal and experimental work will support the model as a whole.

Future work may further improve on issues of measurement in this study. We employed self-report measures of health. Although work supports the validity of self-report measures of health (Miilunpalo et al., 1997), future research should examine associations using biomarker or clinical measures of health. We also used self-report measures of other measures associated with structural discrimination. Future work might include objective measures of structural discrimination, such as residential segregation measured at the community level given its association with health disparities (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2003; Landrine and Corral, 2009). Similarly, future work might assess neighborhood poverty given its associations with health and well-being (Ludwig et al., 2012). Although we used a well-validated measure of perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale; Stucky et al., 2011), reliability of the stress measure was low in the current sample. Future research examining these associations might employ other measures of stress. Additionally, we drew on education as our primary indicator of socioeconomic status in this study, while also reporting on other variables relevant to socio-economic status, including food insecurity and financial stress. Future studies should examine income specifically in relation to these associations given that income plays an important role in associations between discrimination and health (Nazroo, 2003; Williams et al., 2010). Many of our measures employed five-point Likert-type scales, which have been critiqued for yielding extreme response styles among members of certain racial/ethnic groups (Smith and Fischer, 2008; Weijters et al., 2010). This could contribute, for example, to low scores on our measure of frequency of everyday discrimination. Future studies testing these associations should employ four- or six-point Likert-type scales when measuring similar constructs.

We used the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Stucky et al., 2011) to measure participants’ experiences of interpersonal discrimination. Recent work highlights issues with using discrimination scales with multi-racial/ethnic samples, suggesting that reported frequency of discrimination varies depending on how scales are presented and that items may perform differently among participants of different races/ ethnicities (Shariff-Marco et al., 2011). Future researchers should evaluate the proposed model with different measures of discrimination. We found no evidence of model variance across races/ethnicities in this study; however, this may not be widely generalizable given that our sample was relatively homogeneous. Most participants lived in an urban, low-resource setting. Future researchers should evaluate whether processes linking everyday discrimination with health outcomes vary between races/ethnicities within more heterogeneous samples.

Conclusion

This study contributes to understanding of associations between frequency of everyday discrimination and health by addressing several previously identified gaps in research. Knowledge of the processes whereby discrimination is associated with poor health outcomes can inform targets for intervention to improve health among people experiencing discrimination. For example, this study suggests that interventions to reduce stress and depressive symptoms may enhance health among people experiencing discrimination. Beyond these shorter term targeted interventions to improve health at the individual level, it is ultimately critical to eliminate discrimination to reduce health disparities at the population level.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Community Alliance for Research and Engagement for their thoughtful feedback on this work.

Funding

Funding for this study came from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation and The Kresge Foundation, Emerging and Promising Practices. This research was conducted in affiliation with Community Interventions for Health, Oxford Health Alliance, Oxford, England. The project was further supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, T32MH020031, which funded Drs Earnshaw’s and Rosenthal’s effort.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Lochner KA, Osypuk TL, et al. Future directions in residential segregation and health research: A multilevel approach. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):215–221. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks AD, Kohn-Wood LP, Spencer M. An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Mental Health Journal. 2006;42(6):555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman A, Bull F, Chey T, et al. The international prevalence study on physical activity: Results from 20 countries. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2009;6(21):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Jacobs DR, Williams DR, et al. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adults Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166(9):1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Murry VM, et al. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Brady N, Thompson S, et al. Perceived racism and negative affect: Analyses of trait and state measures of affect in a community sample. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27(2):150–173. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broudy R, Brondolo E, Coakley V, et al. Perceived ethnic racism in relation to daily moods and negative social interactions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30(1):31–43. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT. Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist. 2007;35(1):13–105. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2010 emergency department summary tables. 2010 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf.

- Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essed P. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Spencer MS, Chen J, et al. A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(7):1275–1282. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnabs T. Required sample size and power for SEM. 2008 Available at: http://timo.gnambs.at/en/scripts/powerforsem.

- Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e26–e32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R, Tobias M, Jeffreys M, et al. Racism and health: The relationship between experience of racial discrimination and health in New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(6):1428–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert TB, Cohen S. Depression and immunity: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):472–486. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48(1):191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Corral I. Separate and unequal: Residential segregation and black health disparities. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19:179– 184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, et al. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(4):596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SK, Triplett T, Dutwin D. The Massachusetts Health Reform Survey. 2012 Available at: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411649_mass_reform_survey.pdf.

- Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science. 2012;337(6101):1505–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1224648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1(2):130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, et al. Self-rated health status as a health measure: The predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50(5):517–528. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Description. Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Available at: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2012/srvydesc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nazroo JY. The structuring of ethnic inequalities in health: Economic position, racial discrimination, and racism. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):277–284. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, et al. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(2):205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleis JR, Ward BW, Lucas JW. Summary Health Statistics for US Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Martinez D, Carvajal SC. Bicultural stress and adolescent risk behaviors in a community sample of Latinos and non-Latino European Americans. Ethnicity & Health. 2007;12(5):443–463. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruo B, Rumsfeld JS, Hlatky MA, et al. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: The heart and soul study. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(2):215–221. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, et al. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(7):1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariff-Marco S, Breen N, Landrine H, et al. Measuring everyday racial/ethnic discrimination in health surveys: How best to ask the questions, in one or two stages, across multiple racial/ethnic groups? Du Bois Review. 2011;8(1):159–177. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RL, Simmons LG, Burt CH, et al. Supportive parenting moderates the effect of discrimination upon anger, hostile view of relationships, and violence among African American boys. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(4):373–389. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PB, Fischer R. Acquiescence, extreme bias and culture: A multilevel analysis. In: Van de Vijver FJR, Van Hemert DA, Poortinga YH, editors. Multilevel Analysis of Individuals and Cultures. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2008. pp. 285–314. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen PR, Bowden M. Sleep disturbance mediates the relationship between perceived racism and depressive symptoms. Ethnicity & Disease. 2006;16(1):16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavorial medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16(3):199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky BD, Gottfredson NC, Panter AT, et al. An item factor analysis and item response theory-based revision of the Everyday Discrimination Scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17(2):175–185. doi: 10.1037/a0023356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weich S, Lewis G. Poverty, unemployment, and common mental disorders: Population based cohort study. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1998;317:115–119. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7151.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijters B, Cabooter E, Schillewaert N. The effect of rating scale format on response styles: The number of response categories and response category labels. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2010;27(3):236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Whooley MA, De Jonge P, Vittinghoff E, et al. Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(20):2379–2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, et al. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]