Abstract

Purpose

The presumption that board certification directly affects the quality of clinical care is a topic of ongoing discussion in medical literature. Recent studies have demonstrated disparities in patient outcomes associated with type of anesthesia provided for total knee arthroplasties (TKA); improved outcomes are associated with neuraxial (or regional) versus general anesthesia. Whether board certified (BC) and non-board certified (nBC) anesthesiologists make different choices in the anesthetic they administer is unknown. The authors sought to study potential associations of board certification status with anesthesia practice patterns for TKA.

Method

The authors accessed records of anesthetics provided from 2010 to 2013 from the National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry database. They identified TKA cases using Clinical Classifications Software and current procedural terminology codes. The authors divided practitioners into two groups: those who were BC and those who were nBC. For each of these groups, the authors compared the following: their patient populations, the hospitals in which they worked, the nature of their practices, and the anesthetics they administered to their patients.

Results

BC anesthesiologists provided care for 81.7% of 97,508 patients having TKA; 18.3% were treated by nBC anesthesiologists. BC anesthesiologists administered neuraxial/regional anesthesia more frequently than nBC anesthesiologists (41.4% vs. 21.2%; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

The rates at which regional/neuraxial anesthesia were administered for TKA were relatively low, and there were significant differences in practice patterns of BC and nBC anesthesiologists providing care for patients undergoing TKA. More research is necessary to understand the causes of these disparities.

To standardize the qualifications of physicians practicing medicine, specialty boards formalized voluntary specialty-specific board certification.1–3 As one of the 24 boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), the American Board of Anesthesiology (ABA) issues certificates to licensed physicians who successfully demonstrate competency through a written and oral examination.4 While certification is not a sine qua non for the practice of medicine, hospital privileges5–7 and patients’ choice of physician8,9 may depend on whether or not a physician holds board certification. Additionally, some evidence shows patients expect their physicians to actively maintain board certification status.10,11 In a 1998 survey of its membership, the American Medical Association (AMA) found that 87% of the responding 635,000 licensed physicians were board certified (BC).12

The assumption that board certification directly, positively affects the quality of clinical care delivered by, and the practice patterns of, physicians is a topic of ongoing discussion in medical literature.2,13–16 Studies have demonstrated that medical residents who receive positive evaluations from their program directors are likely to pass board certification exams.17,18 These studies validate board certification examinations as a metric of specialty knowledge. The correlation of board examination pass-rates with clinical outcomes is, however, not firmly established. Sharp and colleagues19 reviewed 33 articles published between 1966 and 1999 that addressed the relationship between board certification and clinical outcomes. While board certification is reflected in several aspects of improved clinical care (e.g., decreased mortality and improved quality),2,17 Sharp and colleagues19 reported that just over 50% of studies they reviewed demonstrated significantly improved outcomes for patients of physicians with board certification. The remainder of the studies showed no relationship. Importantly, Sharp and colleagues did not identify any cases for which board certification was associated with poorer outcomes.19 The suggestion of improved outcomes for patients of BC physicians continues to motivate further investigation of the association between board certification and the quality of patient care.16,20 Related to this research, recently published studies have examined the role that participation in maintenance of certification (MOC) plays in clinical outcomes and practice patterns.21–23 Participation in MOC may be important as physicians have a limited ability to self-assess their performance and knowledge gaps,24 and as the number of years in practice increases, the quality of care physicians provide may decrease.24,25

Since a relative paucity of data on anesthetic administration as it relates to board certification is available, we sought to examine the association of board certification and anesthetic practice patterns for total knee arthroplasty (TKA), a common procedure that can be performed after the administration of general, regional, or neuraxial (i.e., nerve block) anesthesia. The number of TKA surgeries performed each year has increased dramatically over the past fifteen years; currently over 700,000 TKA surgeries are performed annually.26 Studies have suggested variability of patient outcomes based on the anesthestic received for the arthroplasty. Regional anesthetics offer several advantages over general anesthesia and, as with many orthopedic surgeries, TKAs can be performed using regional anesthesia.27 Recent analyses have demonstrated that patients who received either neuraxial or regional anesthesia as the primary anesthetic during TKA had better postoperative outcomes (i.e., decreased 30-day mortality, lower incidence of prolonged length of stay, and fewer in-hospital complications) than patients who received a general anesthetic for the same procedure.28–31 Additionally, research has demonstrated that patients receiving regional anesthesia report decreased postoperative pain, consume less morphine, and experience fewer opioid-related adverse events.32 We have previously described the variations in anesthetic technique for TKA using the National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry (NACOR) of the Anesthesia Quality Institute (AQI).33 Significant factors associated with variation in anesthesia technique include the following: patient age, patient acuity as measured by American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, and physician board certification status.33 However, the role of board certification status requires further investigation. Considering the findings of our previous study,33 we have restricted the NACOR database to the appropriate study population to determine whether the frequency with which a particular anesthetic technique was used depended on the anesthesiologist's board certification status.

Using the Participant User File (PUF), a de-identified aggregation of all cases in NACOR, we intended to examine whether differences in anesthetic practice patterns exist between BC and non-board certified (nBC) physicians. We hypothesized that practice patterns between BC and nBC physicians would vary significantly and that BC physicians would administer a regional or neuraxial anesthetic more frequently than their nBC counterparts. We did not attempt to assess differences in outcomes associated with board certification status in this study.

Method

Data source

After receiving approval for the study from the Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medical Center, we collected data for all TKAs performed between January 2010 and June 2013 that were entered into NACOR. No informed consent was required for these study activities. We queried the data on June 24, 2013, at which time the database contained information on a total of 10,065,800 medical records from over 100 heterogeneous sources.34 All records were de-identified and contained information including patient demographics, billing details, and procedural, diagnostic, and provider-specific information.

Study sample

We identified records for primary TKAs using billing data through a code-based search process. We included cases if they contained either (1) a Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) label of “Arthroplasty Knee” or (2) a non-missing CCS label and a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code for knee arthroplasty (27440, 27441, 27442, 27443, 27445, 27446, or 27447). Cases with knee revision CPT codes of 27486 or 27487 were not included in this sample because these procedures, which are longer, generally performed on older patients, and often performed in a small subset of more specialized hospitals, may have skewed the results of this study.

We further restricted the data by excluding records for procedures performed under the direction of someone other than an anesthesiologist (for example, cases either managed by a certified registered nurse anesthetist [CRNA] or reported as not having any anesthesia provider present). We also excluded cases if they were missing the following information: practice-certification status, board certification status, patient age, facility type or location, and duration of anesthesia. Additionally, we excluded cases if an anesthesia technique other than general, neuraxial, or regional was used—that is, we excluded cases using multiple anesthesia types, Monitored Anesthesia Care, sedation, local anesthetic, or other.

Demographic, provider and facility variables

We compared patient demographic information, procedure, and facility characteristics by the certification status of the anesthesiologist providing care. General patient demographics included age, gender, and ASA physical status. Information pertaining to the procedure itself included the anesthesia type (either [1] general or [2] neuraxial or regional), the year the procedure was performed, involvement by residents or CRNAs, and the anesthesia duration. Facility-related characteristics included whether the procedure was performed in a university hospital, large community hospital with more than 500 beds, medium community hospital with 100-500 beds, small community hospital with fewer than 100 beds, other type of facility, or facility that was unclassifiable given the information provided to NACOR. Additionally, we recorded the region of the United States where each NACOR anesthesia case occurred (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West).

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to identify differences based on board certification status. For categorical variables (e.g., gender, anesthesia type) we presented frequencies and proportions; for continuous variables with a skewed distribution (e.g., age, ASA class) we presented the median and interquartile ranges (Q1; Q3). Estimated differences in the characteristics described above by board certification status were evaluated by the Pearson's chi-square test or t-test as appropriate.

We employed multinomial logistic regression to determine whether board certification of providers was associated with general, neuraxial or regional, or missing anesthesia type, while controlling for additional factors (patient age, patient gender, ASA physical status, year, duration of anesthesia, whether residents were present, whether CRNAs were present, facility type, and facility region). This model is a variant of the standard logistic regression and produces odds ratios for the relative odds of a predictor variable's association with each category (administration of neuraxial or regional anesthesia or those missing anesthesia type) and the reference category (administration of general anesthesia). Due to the potential concern of clustering of patient outcomes within anesthesiologist-provider, we also performed multivariable generalized estimating equation (GEE) modeling (with correction for clustering by anesthesiologist-provider) using the same variables as specified in the multivariable logistic regression model. Before running the regression models, we diagnosed multi-collinearity for all the covariates in the models. Variance inflation factors were all below 10, indicating that all of the covariates were in low degree of collinearity to each other, so no further investigation was needed. We explored likelihood ratio tests in all multinomial logistic regression models. All likelihood ratio score and Wald tests agreed and were significant, indicating that the large-sample approximations were working well and the results were trustworthy. We considered P values of < 0.05 to indicate significance between groups. We used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to perform all statistical analyses.

Sensitivity analyses

The records that either lacked board certification status or that listed non-standard anesthesia techniques were excluded as their inclusion could affect the modeling of the association between relevant covariates and anesthesia technique. To quantify the effect of excluding these records, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. To do this, we compared four alternative regression models with anesthesia technique as the dependent variable (Contact the authors for full details). We compared the odds ratios of these models and assessed the influence of different treatments of missing BC status.

Results

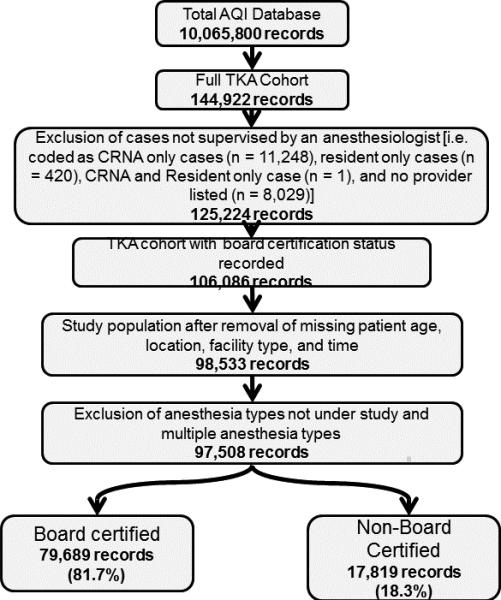

We examined 144,922 records of patients undergoing primary TKA (1.4% of the 10,065,800 total NACOR records). After removing cases not managed by an anesthesiologist (n = 19,698), records missing board-certification status (n = 19,138), cases lacking other key demographics (n = 7,553), records listing multiple anesthesia types (n = 366), and records listing anesthesia types not under study (n = 659), the study population contained 97,508 cases. Of those 97,508 cases, a BC anesthesiologist provided care for 81.7% (n = 79,689) patients and by a nBC anesthesiologist for 18.3% (n = 17,819; see Figure 1) of patients.

Figure 1.

Study population from the Anesthesia Quality Institute (AQI): January 2010 to June 2013. Abbreviations: TKA, total knee arthroplasty; CRNA, Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist.

Table 1 presents patient-related characteristics by board certification status of the physician. We noted statistically significant differences in age and ASA physical status among patients cared for by BC and nBC anesthesiologists. In addition, we found BC anesthesiologists administered neuraxial or regional anesthesia (41.4% of the cases) more frequently than they administered general anesthesia (35.5% of the cases; see Table 2). In contrast, nBC anesthesiologists used general anesthesia (62.2% of the cases) more frequently than they did neuraxial or regional anesthesia (21.2% of the cases). The distributions of anesthesia type administration for BC and nBC anesthesiologists differed significantly (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

General Demographics of Patients Undergoing Knee Arthroplasty, by Board Certification Status of the Physician, National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry, January 2010 – June 2013a

| Category | Board certified, no. (%b of 79,689) | Not board certified, no. (%b of 17,819) | All, no. (%b of 97,508) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agec (Years) | < 0.001 | |||

| 0-44 | 4,181 (5.2) | 985 (5.5) | 5,166 (5.3) | |

| 45-54 | 8,760 (11.0) | 1,808 (10.1) | 10,568 (10.8) | |

| 55-64 | 23,383 (29.3) | 4,989 (28.0) | 28,372 (29.1) | |

| 65-74 | 26,362 (33.1) | 6,058 (34.0) | 32,420 (33.2) | |

| 75+ | 17,003 (21.3) | 3,979 (22.3) | 20,982 (21.5) | |

| Gender | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 30,399 (38.1) | 6,216 (34.9) | 36,615 (37.6) | |

| Female | 49,218 (61.8) | 10,022 (56.2) | 59,240 (60.8) | |

| Missing | 72 (0.1) | 1,581 (8.9) | 1,653 (1.7) | |

| ASA physical statusd | < 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 13,938 (17.5) | 1,448 (8.1) | 15,386 (15.8) | |

| 2 | 26,267 (33.0) | 7,366 (41.3) | 33,633 (34.5) | |

| 3 or higher | 26,791 (33.6) | 6,382 (35.8) | 33,173 (34.0) | |

| Missing | 12,693 (15.9) | 2,623 (14.7) | 15,316 (15.7) | |

Abbreviation: ASA indicates American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Patients of board-certified physicians constitute 81.7% of the sample; patients of non-board-certified physicians constitute 18.3% of the sample.

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

For patients of board-certified physicians, the median age was 66 years [interquartile ranges in years (Q1: 58; Q3: 73)]. For patients of non-board-certified physicians, the median age was 66 years [interquartile ranges in years (Q1: 59; Q3: 74)]. For all patients in the sample, the median age was 66 years [interquartile ranges in years (Q1: 58; Q3: 73)] (P = 0.01).

For patients of board-certified physicians, patients of non-board-certified physicians, and all patients in the sample, the median ASA physical status was 2, the median quartile 1 ASA class was 2, and the median quartile 3 ASA class was 3 (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Intraoperative Statistics for Knee Arthroplasty, by Board Certification Status ofthe Physician, National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry, January 2010 – June 2013a

| Category | Board certified, no. (%b of 79,689) | Not board certified, no. (%b of 17,819) | All, no. (%b of 97,508) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia type | < 0.001 | |||

| Only general | 28,315 (35.5) | 11,075 (62.2) | 39,390 (40.4) | |

| Neuraxial or regional | 32,958 (41.4) | 3,769 (21.2) | 36,727 (37.7) | |

| Missing | 18,416 (23.1) | 2,975 (16.7) | 21,391 (21.9) | |

| Year | < 0.001 | |||

| 2010 | 23,279 (29.2) | 3,111 (17.5) | 26,390 (27.1) | |

| 2011 | 24,591 (30.9) | 4,602 (25.8) | 29,193 (29.9) | |

| 2012 | 25,828 (32.4) | 7,866 (44.1) | 33,694 (34.6) | |

| 2013 | 5,991 (7.5) | 2,240 (12.6) | 8,231 (8.4) | |

| Anesthesia providers | < 0.001 | |||

| Resident involvement | 5,526 (6.9) | 562 (3.2) | 6,088 (6.2) | |

| CRNA involvement | 32,613 (40.9) | 9,164 (51.4) | 41,777 (42.8) | |

| Duration of anesthesia | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 to < 1.5 hours | 5,227 (6.6) | 1,326 (7.4) | 6,553 (6.7) | |

| 1.5 hours to < 2 hours | 19,457 (24.4) | 3,919 (22.0) | 23,376 (24.0) | |

| 2 hours to < 2.5 hours | 27,870 (35.0) | 5,692 (31.9) | 33,562 (34.4) | |

| 2.5 hours or more | 27,135 (34.1) | 6,882 (38.6) | 34,017 (34.9) | |

Abbreviaton: CRNA signifies certified registered nurse anesthetist.

Patients of board-certified physicians constitute 81.7% of the sample; patients of non-board-certified physicians constitute 18.3% of the sample.

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

c For the cases of board-certified physicians, the median anesthesia duration in minutes was 135 [interquartile ranges in minutes (Q1: 114; Q3: 161)].. For the cases of non-board-certified physicians, the median anesthesia duration in minutes was 138[interquartile ranges in minutes (Q1: 115; Q3: 166)]. For all cases in the sample, the median anesthesia duration in minutes was 135 [interquartile ranges in minutes (Q1: 114; Q3: 162)].

Compared with nBC cases, a higher proportion of BC cases involved residents (3.2% vs. 6.9%; P < 0.001). However, the opposite was true for cases that involved CRNAs. When compared to nBC cases, a lower proportion of BC cases involved CRNAs (51.4% vs. 40.9%; P < 0.001; see Table 2). Additionally, compared with nBC cases, a higher proportion of BC cases were administered by only an attending (52.2% and 45.4%; P < 0.001; not shown). When at least one resident participated in the procedure, median duration of anesthesia was significantly longer compared to procedures completed without anesthesiology residents (154 minutes vs. 134 minutes, respectively; P < 0.001; not shown).

Most procedures—by both BC and nBC anesthesiologists—were performed at medium-sized community hospitals. Large community hospitals were the setting for the second greatest percent of cases; BC anesthesiologist administered more cases in these hospitals than nBC anesthesiologists (respectively, 24.1% vs. 8.8%; P < 0.001; see Table 3). TKA cases for both BC and nBC were most often performed in the Midwest (BC: 39.1%; nBC: 32.1%; P < 0.001; see Table 3).

Table 3.

Hospital Statistics for Knee Arthroplasty, by Board Certification Status of the Physician, National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry, January 2010 – June 2013a

| Category | Board certified, no. (%b of 79,689) | Not board certified, no. (%b of 17,819) | All, no. (%b of 97,508) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility type | < 0.001 | |||

| University hospital | 2,959 (3.7) | 191 (1.1) | 3,150 (3.2) | |

| Large community hospital (over 500 beds) | 19,211 (24.1) | 1,571 (8.8) | 20,782 (21.3) | |

| Medium community hospital (100-500 beds) | 47,865 (60.1) | 8,885 (49.9) | 56,750 (58.2) | |

| Small community hospital (fewer than 100 beds) | 4,185 (5.3) | 431 (2.4) | 4,616 (4.7) | |

| Unclassifiable | 1,604 (2.0) | 6,324 (35.5) | 7,928 (8.1) | |

| Otherc | 3,865 (4.9) | 417 (2.3) | 4,282 (4.4) | |

| Region | < 0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 8,700 (10.9) | 3,906 (21.9) | 12,606 (12.9) | |

| Midwest | 31,189 (39.1) | 5,721 (32.1) | 36,910 (37.9) | |

| South | 28,625 (35.9) | 4,028 (22.6) | 32,653 (33.5) | |

| West | 11,175 (14.0) | 4,164 (23.4) | 15,339 (15.7) | |

Patients of board-certified physicians constitute 81.7% of the sample; patients of non-board-certified physicians constitute 18.3% of the sample.

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Facility types: Specialty hospital, attached surgery center, freestanding surgery center, pain clinic, surgeon office

Logistic regression results

The multinomial logistic regression modeling conducted to identify whether board certification status was associated with anesthetic technique showed that indeed BC physicians had increased odds of administering neuraxial or regional anesthesia (odds ratio: 2.06; confidence intervals: 1.97, 2.17; P < 0.0001) relative to general anesthesia (See Table 4). GEE analysis did not alter the significance of the board certification status finding (P < 0.0001). Because all of the findings from the GEE model were consistent with the standard logistic regression model, with only negligible differences in the standard error estimates of the adjusted odds ratios, we have reported only the logistic regression results.

Table 4.

Results from Logistic Regression Model for the Outcome of Anesthesia Type, National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry, January 2010 – June 2013

| Category | Neuraxial or regional anesthesia, Odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) | Missing anesthesia type, Odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) |

|---|---|---|

| Board certification | ||

| Reference: No | ||

| Yes | 2.06b (1.97, 2.17) | 0.90a (0.84, 0.97) |

| Age group | ||

| 0-44 | 0.22b (0.20, 0.24) | 0.77b (0.69, 0.85) |

| 45-54 | 0.83b (0.79, 0.88) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.09) |

| Reference: 55-64 | ||

| 65-74 | 1.20b (1.16, 1.25) | 0.93a (0.88, 0.99) |

| 75+ | 1.22b (1.17, 1.27) | 0.83b (0.77, 0.89) |

| Gender | ||

| Reference: Male | ||

| Female | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) |

| Missing | 0.12b (0.10, 0.14) | 0.02b (0.00, 0.07) |

| ASA Physical Status | ||

| Reference: 1 | ||

| 2 | 1.89b (1.79, 1.98) | 0.02b (0.01, 0.02) |

| 3 or more | 1.43b (1.36, 1.51) | 0.58b (0.55, 0.63) |

| Missing | 0.40b (0.37, 0.44) | 13.55b (12.45, 14.76) |

| Year | ||

| Reference: 2010 | ||

| 2011 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.17) |

| 2012 | 1.16b (1.12, 1.21) | 0.79b (0.75, 0.85) |

| 2013 | 1.21b (1.14, 1.29) | 0.59b (0.53, 0.66) |

| Duration of Anesthesia | ||

| 0 to < 1.5 hrs | 0.78b (0.73, 0.83) | 1.42b (1.28,1.57) |

| 1.5 hrs to < 2 hrs | 1.18b (1.13, 1.23) | 1.58b (1.48, 1.68) |

| Reference: ≥ 2 to < 2.5 hrs | ||

| 2.5 hrs or more | 0.73b (0.70, 0.75) | 1.13b (1.07, 1.19) |

| Resident present | ||

| Reference: No | ||

| Yes | 1.01 (0.93, 1.09) | 1.21a (1.08, 1.36) |

| CRNA present | ||

| Reference: No | ||

| Yes | 0.94b (0.91, 0.97) | 0.94 (0.89, 1.00) |

| Missing | 0.95 (0.88, 1.01) | 7.30 (6.73, 7.91) |

| Facility typec | ||

| UH | 2.02b (1.73, 2.36) | 10.85b (9.02, 13.05) |

| LCH | 1.26b (1.21, 1.32) | 1.36 (1.27, 1.46) |

| Reference: MCH | ||

| SCH | 1.35b (1.26, 1.45) | 0.80b (0.70, 0.91) |

| Other | 0.37b (0.33, 0.40) | 0.87a (0.78, 0.96) |

| Unclassifiable | 0.31b (0.28, 0.33) | 0.62b (0.55, 0.70) |

| Region | ||

| Reference: Northeast | ||

| Midwest | 1.53b (1.45, 1.61) | 100.22b (78.46, 128.02) |

| South | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 153.93b (121.16, 195.57) |

| West | 1.09a (1.01, 1.17) | 29.65b (23.19, 37.90) |

P < 0.05

P < 0.001

UH indicates university hospital; LCH, large community hospital with more than 500 beds; MCH, medium community hospital with 100-500 beds; SCH, small community hospital with fewer than 100 beds; Other, other type of facility; Unclassifiable, facilities unable to be classified with the information provided.

Sensitivity analyses

The four logistic regression models we performed with variegated treatment of missing values for our sensitivity analyses confirm that the exclusion of certain records [see Method]) yielded similar results and identical conclusions for variables of interest (results not shown).

Discussion

Through our analysis of data from a large national anesthesia database, we identified several significant characteristics that differentiated the practice of BC and nBC anesthesiologists. Differences exist in both the demographics of the patients treated and the choice of anesthetic technique.

A previous finding of variability in anesthetic care in TKA33 required further investigation with a focus on board certification status and we have presented those findings here. We found that BC anesthesiologists more often chose neuraxial or regional anesthesia for patients having TKA surgery compared to nBC anesthesiologists; however, this association was slightly lower than that found in previous study (neuraxial vs. general [odds ratio: 3.44; confidence intervals: 3.30, 3.59; P < 0.001]; regional vs. general [odds ratio: 2.43; confidence intervals: 2.29, 2.58; P < 0.001]).33 The implications of anesthesia technique are highly relevant considering current developments in TKA-focused anesthesia research. As noted in the Introduction, Memtsoudis and colleagues28,31have demonstrated that the use of neuraxial anesthesia, as opposed to general anesthesia, for TKAs is associated with a significant decrease in 30-day mortality as well as lower incidence of prolonged length of stay and fewer in-hospital complications. In spite of improved outcomes,28,30,31 the physicians in our study used neuraxial or regional anesthesia techniques less frequently than expected. Only 41% of BC anesthesiologists chose either a neuraxial or regional anesthetic for TKA (and only 21% of nBC anesthesiologists chose this technique). The low use of neuraxial or regional anesthesia may be attributed to a few factors. The acceptance of these anesthesia types for TKAs as an optimal practice pattern has occurred relatively recently,35 so these techniques may not have been widely disseminated and adopted. Using the diffusion of innovations theory,36 the centers/anesthesia providers employing regional or neuraxial anesthetic techniques may be functioning as the innovators or early-adopters in this diffusion process. The widespread use of these anesthetic techniques hinges on three key elements: communication (through additional studies and dissemination of improved outcomes), time, and the social system (acceptance by organizations and influential leaders in the field). The greater dissemination of regional and neuraxial techniques for TKA, therefore, requires the on-going education and encouragement of anesthesiologists in practice and in training.

We also found that, compared to their BC colleagues, nBC anesthesiologists more frequently treated older patients and patients with higher ASA physical status classification. Individuals older than 65 have higher rates of adverse perioperative events37–43; likewise patients with higher ASA physical status classification are also at an increased risk of experiencing postoperative complications.44–47 (This study was not intended to analyze patient outcomes and this information is not consistently included in the NACOR database)

A secondary finding of this study is the difference in duration of anesthesia for TKA between BC (135 minutes) and nBC anesthesiologists (138 minutes). This difference is minimal, but the duration of anesthesia for the BC anesthesiologists may be inflated because these physicians more frequently work with residents; however, this potential cause is speculative, and the implications of this finding related to outcomes remains to be studied.

An incidental outcome

In addition to deriving descriptive statistics from the data, we also demonstrated the utility of the novel AQI database for investigating practice patterns. In the current climate of intensive data collection and proliferation of clinical databases, deciding which database to use can be difficult. The choices vary from commercial to publicly available databases. Recent literature has responded to the surge of nationwide sources of data, and authors have highlighted the advantages and limitations of these databases.48 The AQI database was specifically designed to collect extensive information pertaining to anesthesia including provider-specific information. This database contains survey data from anesthesia providers throughout the United States; submissions come from providers at both large and small hospitals, as well as from academic and private practice settings. This diversity enables a cross-sectional perspective on national anesthesia practice patterns and makes the AQI database ideal for descriptive statistics of practice patterns.

Limitations

This study has identified differences in practice patterns between BC and nBC providers; however, despite our examination of many anesthesiologist demographics, practice characteristics, and patient demographics, the reasons for these differences have not been elucidated. Additionally, given the recent evidence demonstrating improved outcomes with the use of neuraxial or regional anesthesia for TKAs relative to general anesthesia,28–31 it is unclear why anesthesiologists—whether BC or nBC—do not use these techniques more frequently. Importantly, these findings may not incorporate recommended practice patterns due to the years of the data analyzed during this investigation. Since publications demonstrating improved outcomes were disseminated toward the end of the study period, an investigation of more recent data may yield different results. Additional study is necessary to better understand the reason for these practice patterns.

The main limitation of this investigation is inherent to the study of information contained in a database. Use of a database allows for only secondary, retrospective analysis of data. Secondly, the AQI database has certain specific limitations. While providing the benefit of collecting data from diverse facilities and providers, a disadvantage is that the data are marked by a range of entry patterns. The same information may be entered differently by small and large hospitals. Data entry errors or miscoding may lead to the misclassification of some records. This miscoding, though, is likely to affect the groups of BC and nBC anesthesiologists similarly, and therefore to have minimal effect on the overall findings. Furthermore, larger facilities that store more of their patient information electronically tend to submit information for more fields per case than smaller facilities. The lack of uniform entry procedures leads to a large amount of missing data, making it difficult to draw conclusions from many of the entered variables. For example, although the NACOR database of AQI currently allows facilities to enter outcomes-related information, the information may be entered in a number of different formats preventing study of perioperative or postoperative outcomes. Finally, AQI data lack information related to the surgical team and surgical resident involved in the procedure, making it difficult to fully interpret potential differences in anesthesia time between groups.

Conclusions

In summary, to our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the association between anesthesiologist board certification and anesthesia practice patterns in TKA surgeries. We found that compared to nBC anesthesiologists, BC anesthesiologists used either a regional or neuraxial anesthetic more often as the anesthetic for TKA. The association was slightly lower than previously identified,33 but the effect was still significant. In light of the increase in the number of TKAs performed annually in the United States, and given the desire to improve anesthetic management for this particular surgery and in turn patient outcomes, further investigation is necessary. Ultimately, database analyses, such as this, can identify areas of need for further education for anesthesiologists.

Acknowledgements

This represents the work of the Center for Perioperative Outcomes, Department of Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical College/New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

The authors acknowledge the Anesthesia Quality Institute and the National Anesthesia Clinical Outcomes Registry for sharing data that made the preparation of this manuscript possible. Further, the authors would like to thank Dr. Madhu Mazumdar, Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Department of Public Health, Weill Cornell Medical College for her guidance, as well as, the Clinical and Translational Science Center, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Funding/support: Funding for this project was provided by the Center for Perioperative Outcomes, Department of Anesthesiology at the Weill Cornell Medical College/New York-Presbyterian Hospital; the Anna Maria and Stephen Kellen Clinician Scientist Career Development Award; and CTSC grant number 5 UL1 TR000457-07.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: Reported as none.

Ethical approval: The Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medical College approved this project.

Previous presentations: An abstract representing this work was presented at the American Society of Anesthesiology annual meeting in San Francisco, California, October 2013.

Contributor Information

Peter M. Fleischut, Weill Cornell Medical College, and attending anesthesiologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, New York..

Jonathan M. Eskreis-Winkler, Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Department of Public Health, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York..

Licia K. Gaber-Baylis, Department of Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York..

Gregory P. Giambrone, Department of Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York..

Xian Wu, Department of Healthcare Policy and Research, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York..

Xuming Sun, Department of Healthcare Policy and Research, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York..

Cynthia A. Lien, Weill Cornell Medical College, and attending anesthesiologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, New York..

Susan L. Faggiani, Department of Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York..

Richard P. Dutton, the University of Chicago, and executive director, Anesthesia Quality Institute, American Society of Anesthesiologists, Park Ridge, Illinois..

Stavros G. Memtsoudis, Department of Anesthesiology, Hospital for Special Surgery, and clinical professor of anesthesiology and public health, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York..

References

- 1.American Board of Medical Specialties . About ABMS. [May 20, 2015]. http://www.abms.org/about-abms/. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan TA, Horwitz RI, Duffy FD, Cassel CK, Goode LD, Lipner RS. The role of physician specialty board certification status in the quality movement. JAMA. 2004;292:1038–1043. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dairiki Shortliffe LM. Certification, recertification, and maintenance: Continuing to learn. Urol Clin North Am. 2009;36:79–83. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Board of Anesthesiology [May 20, 2015];About the ABA. 2015 http://www.theaba.org/Home/About.

- 5.Lowy J. Board certification as prerequisite for hospital staff privileges. Virtual Mentor. 2005:7. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2005.7.4.ccas4-0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freed GL, Uren RL, Hudson EJ. Policies and practices related to the role of board certification and recertification of pediatricians in hospital privileging. JAMA. 2006;295:905–912. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.8.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freed GL, Singer D, Lakhani I, Wheeler JR, Stockman JA., 3rd Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Use of board certification and recertification of pediatricians in health plan credentialing policies. JAMA. 2006;295:913–918. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.8.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ConsumerReports.org [May 20, 2015];How to find the right surgeon. http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/2012/04/how-to-find-the-right-surgeon/index.htm.

- 9.Chen J, Rathore SS, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Physician board certification and the care and outcomes of elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freed GL, Dunham KM, Clark SJ, Davis MM. Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Perspectives and preferences among the general public regarding physician selection and board certification. J Pediatr.;2010;156:841–5. 845, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Gallup Organization for The American Board of Internal Medicine . Awareness of and attitudes toward board-certificartion of physicians. The Gallup Organization; Princeton, NJ: Aug, 2003. [May 20, 2015]. https://www.abim.org/pdf/publications/Gallup_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Medical Association [May 20, 2015];AMA Physician Masterfile. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about- ama/physician-data-resources/physician-masterfile.page.

- 13.Norcini JJ, Lipner RS, Kimball HR. Certifying examination performance and patient outcomes following acute myocardial infarction. Med Educ. 2002;36:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis JP, Luebbert JJ, Wang Y, et al. Association of physician certification and outcomes among patients receiving an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. JAMA. 2009;301:1661–1670. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmboe ES, Wang Y, Meehan TP, et al. Association between maintenance of certification examination scores and quality of care for medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1396–1403. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosch EN. Does specialty board certification influence clinical outcomes? J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:473–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norcini JJ, Webster GD, Grosso LJ, Blank LL, Benson JA., Jr Ratings of residents’ clinical competence and performance on certification examination. J Med Educ. 1987;62:457–462. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198706000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slogoff S, Hughes FP, Hug CC, Jr, Longnecker DE, Saidman LJ. A demonstration of validity for certification by the American Board of Anesthesiology. Acad Med. 1994;69:740–746. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199409000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharp LK, Bashook PG, Lipsky MS, Horowitz SD, Miller SH. Specialty board certification and clinical outcomes: The missing link. Acad Med. 2002;77:534–542. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeffe DB, Andriole DA. Factors associated with American Board of Medical Specialties member board certification among US medical school graduates. JAMA. 2011;306:961–970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes RS, Biesten TW, Ritchie WP, Malangoni MA. Continuing medical education activity and American Board of Surgery examination performance. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:604–610. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Culley DJ, Sun H, Harman AE, Warner DO. Perceived value of Board certification and the Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology Program (MOCA®). J Clin Anesth. 2013;25:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turchin A, Shubina M, Chodos AH, Einbinder JS, Pendergrass ML. Effect of board certification on antihypertensive treatment intensification in patients with diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2008;117:623–628. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.733949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: The relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:260–273. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Southern WN, Bellin EY, Arnsten JH. Longer lengths of stay and higher risk of mortality among inpatients of physicians with more years in practice. Am J Med. 2011;124:868–874. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsui BC, Rosenquist RW. Peripheral nerve blockade. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Stock MC, editors. Clinical Anesthesia. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2009. pp. 1375–1392. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Memtsoudis SG, Sun X, Chiu YL, et al. Perioperative comparative effectiveness of anesthetic technique in orthopedic patients. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1046–1058. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318286061d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Memtsoudis SG, Ma Y, González Della Valle A, et al. Perioperative outcomes after unilateral and bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1206–1216. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181bfab7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stundner O, Chiu Y-L, Sun X, et al. Comparative perioperative outcomes associated with neuraxial versus general anesthesia for simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37:638–644. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31826e1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Memtsoudis SG, Stundner O, Rasul R, et al. Sleep apnea and total joint arthroplasty under various types of anesthesia: A population-based study of perioperative outcomes. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38:274–281. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31828d0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macfarlane AJ, Prasad GA, Chan VWS, Brull R. Does regional anesthesia improve outcome after total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2379–2402. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0666-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleischut PM, Eskreis-Winkler JM, Gaber-Baylis LK, et al. Variability in anesthetic care for total knee arthroplasty: An analysis from the Anesthesia Quality Institute. AJMQ. 2015;30:172–179. doi: 10.1177/1062860614525989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anesthesia Quality Institute . Homepage. Schaumburg, IL.: 2015. [May 20, 2015]. http://aqihq.org/puf_inquiry.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCartney CJL, Choi S. Does anaesthetic technique really matter for total knee arthroplasty? Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:331–333. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. Free Press; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lubin MF. Is age a risk factor for surgery? Med Clin North Am. 1993;77:327–333. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beecher HK, Todd DP. A study of the deaths associated with anesthesia and surgery: Based on a study of 599, 548 anesthesias in ten institutions 1948-1952, inclusive. Ann Surg. 1954;140:2–35. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195407000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eger EI, Bahlman SH, Munson ES. The effect of age on the rate of increase of alveolar anesthetic concentration. Anesthesiology. 1971;35:365–372. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farrow SC, Fowkes FG, Lunn JN, Robertson IB, Samuel P. Epidemiology in anaesthesia. II: Factors affecting mortality in hospital. Br J Anaesth. 1982;54:811–817. doi: 10.1093/bja/54.8.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tiret L, Desmonts JM, Hatton F, Vourc'h G. Complications associated with anaesthesia—A prospective survey in France. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1986;33(3 Pt 1):336–344. doi: 10.1007/BF03010747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forrest JB, Rehder K, Cahalan MK, Goldsmith CH. Multicenter study of general anesthesia. III. Predictors of severe perioperative adverse outcomes. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:3–15. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwilk B, Muche R, Treiber H, Brinkmann A, Georgieff M, Bothner U. A cross-validated multifactorial index of perioperative risks in adults undergoing anaesthesia for non-cardiac surgery. Analysis of perioperative events in 26907 anaesthetic procedures. J Clin Monit Comput. 1998;14:283–294. doi: 10.1023/a:1009916822005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daabiss M. American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:111–115. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ridgeway S, Wilson J, Charlet A, Kafatos G, Pearson A, Coello R. Infection of the surgical site after arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:844–850. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B6.15121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiret L, Hatton F, Desmonts JM, Vourc'h G. Prediction of outcome of anaesthesia in patients over 40 years: A multifactorial risk index. Stat Med. 1988;7:947–954. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carey MS, Victory R, Stitt L, Tsang N. Factors that influence length of stay for in-patient gynaecology surgery: Is the Case Mix Group (CMG) or type of procedure more important? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28:149–155. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleischut PM, Mazumdar M, Memtsoudis SG. Perioperative database research: Possibilities and pitfalls. Br J Anaesth. 2013;4:532–534. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]