Abstract

Oxalic acid enhances arsenic (As) mobilization by dissolving As host minerals and competing for sorption sites. Oxalic acid amendments thus could potentially improve the efficiency of widely used pump-and-treat (P&T) remediation. This study investigates the effectiveness of oxalic acid on As mobilization from contaminated sediments with different As input sources and redox conditions, and examines whether residual sediment As after oxalic acid treatment can still be reductively mobilized. Batch extraction, column, and microcosm experiments were performed in the laboratory using sediments from the Dover Municipal Landfill and the Vineland Chemical Company Superfund sites. Oxalic acid mobilized As from both Dover and Vineland sediments, although the efficiency rates were different. The residual As in both Dover and Vineland sediments after oxalic acid treatment was less vulnerable to microbial reduction than before the treatment. Oxalic acid could thus improve the efficiency of P&T. X-ray absorption spectroscopy analysis indicated that the Vineland sediment samples still contained reactive Fe(III) minerals after oxalic acid treatment, and thus released more As into solution under reducing conditions than the Dover samples. Therefore, the efficacy of P&T must consider sediment Fe mineralogy when evaluating its overall potential for remediating groundwater As.

Keywords: Arsenic contamination, Oxalic acid, Pump-and-treat, Iron mineralogy, Microbial reduction

1. Introduction

Groundwater arsenic (As) contamination is currently a global public health problem and also a concern at hundreds of U.S. Superfund sites [1, 2]. At many of these sites, groundwater As is derived from anthropogenic As inputs, such as manufacturing and using As-based chemicals, mining, and swine and poultry farming [2]. At other contaminated sites, there are no anthropogenic As inputs but rather naturally occurring As, and groundwater As is mobilized from local host minerals in the sediments via reduction of As-bearing Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides, oxidation of As-bearing sulfides, and competitive desorption from phosphate and other similar ions; these mechanisms can be triggered or intensified by human activities [2-5]. Formulating remedial options at such distinct sites needs to consider these differences [6]. Pump-and-treat (P&T) is widely used for groundwater remediation of point-source pollution, because it limits groundwater migration, and decreases contaminant loading by mobilizing contaminants under controlled conditions [7]. There are currently more than 700 P&T systems in operation at U.S. Superfund sites, requiring operation and maintenance costs over the lifetime of the projects [8]. However, the effectiveness of traditional P&T for As remediation often progressively decreases due to incomplete desorption and other factors. Additions of amendments such as oxalic acid (H2C2O4) that enhance As mobilization from the aquifer matrix are potentially useful to improve P&T efficiency. Oxalic acid is biodegradable and relatively inexpensive, and can be found naturally in environments at concentrations up to 4 mM [9-12]. It can complex and dissolve Fe (oxyhydr)oxides and aluminum (Al) (oxyhydr)oxides, which are often the major As host minerals in aquifers, and can also compete with As oxyanions for sorption sites [11, 13-19]. Our previous studies [20-22] have shown that oxalic acid can accelerate As mobilization from sediments at laboratory to pilot field scales at the Vineland Chemical Company Superfund site, a site with As derived from industrial sources. Given its promising potential in use for enhanced P&T, the transferability of oxalic acid to other sites is worth exploring. Furthermore, any residual sediment As following P&T is still a substantial As reservoir. Whether this residual As can potentially continue to contaminate the groundwater also requires careful investigation.

The objectives of this study were (i) to investigate the effect of oxalic acid on As mobilization at sites with different As input sources and redox conditions; (ii) to examine the impact of microbial reduction on residual sediment As after oxalic acid treatment; and (iii) to inform the prospects for remediating groundwater As contamination using oxalic acid. In this study, sediments from the Dover Municipal Landfill and Vineland Chemical Company Superfund sites were collected and characterized by different techniques including synchrotron based X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and laboratory batch extractions, column flow-through experiments and microcosm incubations were performed on these sediments.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Site and Sample Information

2.1.1 The Dover Municipal Landfill Superfund Site

The Dover site (Dover, New Hampshire) was classified as a Superfund site in 1983, with the primary constituents of concern being volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and As [23]. There is no known anthropogenic As source at this site, and this landfill site is similar to other landfill sites where elevated groundwater As concentrations were caused by the reducing conditions beneath the landfill mobilizing As from unconsolidated local sediments [4, 5]. Traditional P&T and vapor extraction were chosen as the remediation strategies for the Dover site in 2009, and following that decision, a network of extraction wells was installed in 2011 along the down-gradient toe of the landfill. Groundwater VOC concentrations have decreased owing to successful vapor extraction, natural attenuation and degradation processes associated with flushing. Groundwater As concentrations, however, have not decreased and some wells have dissolved As concentrations up to 150 μg L-1. The aquifer sediments used in this study were collected when extraction wells EW1 and EW8b were installed at the southwest and southeast toe, respectively. The sediments were collected immediately following sonic vibration drilling, as top (6-9 m below ground surface (BGS)), middle (9-12 m BGS) and bottom (12-15 m BGS) sediments. Once collected, the sediments were homogenized and refrigerated in steel cans with epoxy liners (0.004 m3 each), and returned to laboratory for experiments. Aliquots of the sediments were preserved in glycerol (to prevent exposure to oxygen and preserve oxidation state) and frozen for XAS analysis. Aliquots of the sediments were also freeze-dried for X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyses, and oven-dried to determine water content.

2.1.1 The Vineland Chemical Company Superfund Site

Arsenic contamination at the Vineland site (Cumberland County, New Jersey) was caused by improper storage of As-containing chemicals and waste products. The sediments used in this study were collected from the aquifer and the vadose zone during several remediation activities, representing a subsample of concentrations present prior to the remediation activities being completed. Descriptions of the site and sediment collection procedures have been published in detail elsewhere [20-22, 24]. Vineland sediments were handled in a similar fashion to Dover sediments.

2.2. Artificial Groundwater Preparation

Synthetic solution media was prepared freshly before each experiment, which began with typical groundwater composition [25, 26] — artificial groundwater (A-GW) and then processed further as needed with additional chemical amendments, pH adjustment and/or nitrogen gas (N2, ultra-high purity) purging. The A-GW consisted of Milli-Q water (18.2 MΩ) amended with 0.02 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM CaCl2, and 0.33 mM Na-lactate.

2.3. Batch Extractions

In each extraction, 2 g of wet sediments were combined with 10 mL of ambient extraction solution. The extraction solutions included 1 mM, 10 mM, and 100 mM oxalic acid containing A-GW. The extraction solutions were used both without pH adjustment, which had pH 3.1, 2.2, and 1.4, respectively, and with pH adjustment (with NaOH or HCl). The suspensions were shaken in polyethylene centrifuge tubes at room temperature for 24 hours. At the end of the extraction, the suspension pH was measured and the suspensions were then centrifuged. The supernatants were filtered to 0.2 μm through nylon membrane syringe filters (Whatman) and analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) for trace metal composition. Batch extractions using oxalate-free A-GW, which were adjusted to the same initial pHs (i.e., pH 3.1, 2.2, and 1.4) with HCl, were conducted for Dover sediments, for comparison with extractions with oxalate to isolate the effect of pH change alone on As mobilization.

2.4. Column Set-up and Flow Condition

To conduct column experiments, Dover sediments were homogenized and mixed with autoclaved sand (50%/50% w/w dry mass, pure sand from Acros Organics, 40-100 mesh) to improve flow properties. The sediments were homogenized in an anaerobic glove box filled with a 95%/5% N2/H2 mixture, and then wet-packed into three identical sections of polycarbonate tube (McMaster-Carr) with 1 cm ID and 0.3 cm walls (Supplementary Material (SM) Figure S1). Glass wool was packed into each end to help distribute solution over the full cross sectional area of the columns. Column lengths packed with sediments were 15 cm. One of the three columns was used for determining effective porosity using a bromide breakthrough curve, which was estimated to be 0.29, similar to the Dover site (between 0.20 and 0.33). The other two columns were treated simultaneously with pH 7.0 A-GW or 10 mM oxalic acid containing A-GW, respectively. The pH 7.0 A-GW was buffered with 10 mM PIPES, whereas 10 mM oxalic acid containing A-GW was unbuffered (other than by oxalic acid) and had an initial pH of 2.2. The influents were purged with N2 throughout the experiment. The columns were oriented vertically with flow going up. The flow was controlled by a peristaltic pump (ISMATEC) at 1 m day-1, to mimic the groundwater velocity during P&T cycles. To condition the columns and remove suspended sediments, both columns started with pH 7.0 A-GW influent for about 2 pore volumes (PVs). Then, one of the columns continued with pH 7.0 A-GW influent for 40 PVs, and is referred to hereafter as column A-GW; the other column switched to oxalic acid influent for 40 PVs, and is referred to hereafter as column OX. A fraction collector (LKB Bromma) was used for collecting column effluents. Some effluent samples were measured for pH immediately following collection. The other effluent samples were filtered to 0.2 μm and analyzed by ICP-MS.

2.5. Microcosm Incubations

Microcosm experiments were performed to study the effect of oxalic acid treatment on sediment As release under reducing conditions. These microcosms were performed by first treating the sediments with oxalic acid, and then adding lactate to a suspension of the treated sediments as described below. For each sediment sample, 12 g of wet sediments were combined with 90 mL of N2-purged 10 mM oxalic acid containing A-GW, purged with N2 for another 15 min before sealed, and reacted at room temperature in constantly agitated high-density polyethylene bottles. After 24 hours, the suspensions were centrifuged, and the supernatants were filtered to 0.2 μm and analyzed by ICP-MS. This extraction process was repeated on the sediments to increase the amount of As extracted, and the resulting treated sediment sample was immediately washed with N2-purged pH 7.0 A-GW. The washed sediments was then divided into six identical 30 mL serum bottles each of which was added with 15 mL of N2-purged 10 mM Na-lactate containing pH 7.0 A-GW. Lactate concentration was elevated to stimulate microbial respiration and create reducing conditions. Each bottle was purged with N2 for another 15 min and sealed with gas-tight blue butyl rubber septa. These microcosms were placed on an orbital shaker at 100 rpm and incubated at room temperature for up to 3 months until sampling. At each sampling event, one of the six microcosms of each sediment sample was sacrificed for ICP-MS analysis. Control microcosms with untreated sediments were run in parallel.

2.6. Analytical Procedures

2.6.1. Solid-Phase Characterization

The freeze-dried sediments were powdered using an alumina shatter box (Angstrom, Inc.) before being analyzed. Sediment bulk mineralogy was determined by XRD (Panalytical X'Pert). XRD patterns over 2-theta angle of 2° to 60° were collected, and constituent minerals were identified using MDI Jade 6 (Materials Data Incorporated). Sediment bulk elemental concentrations were determined by XRF spectroscopy (Spectro Xepos) [22]. XRF accuracy for As and Fe were within 100 ± 6% and 100 ± 10%, respectively, based on certified NIST standards.

Sediment As and Fe speciation/mineralogy were investigated by As X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra and Fe extended X-ray adsorption fine-structure (EXAFS) spectra, respectively. The analysis was carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) on beamlines 11-2 and 4-1. The beamlines each was configured with a Si(220) monochromator and a phi angle of 0 degrees. Sample spectra were collected with a Ge detector in fluorescence mode, in combination with a 6 μx Ge filter for As spectra or a 6 μx Mn filter for Fe spectra. Normalized As XANES spectra were compared with reference spectra of Na-arsenate, Na-arsenite and orpiment (As2S3). The k3-weighted chi functions of Fe EXAFS spectra were fitted using reference spectra of ferrihydrite, goethite, hematite, magnetite, mackinawite, siderite and Fe-containing silicates. Least-squares linear combination fitting was used to quantify the fraction of each reference in the sample. Other As and Fe reference compounds were considered but not needed for fitting based on statistical filters (based on target transforms) nor did they result in better or stable fits. The spectra processing was done in SIXpack [27].

2.6.2. Aqueous Analysis

Trace metal compositions in solution samples were determined by Element XR ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using previously published procedures [24, 28]. Quantification for each element was based on comparison to a six-point standard curve from a multi-element standard. Accuracy was within 100 ± 5% for each element measured, based on certified NIST standards.

2.7. Thermodynamic Modeling

Visual MINTEQ [29] was used for calculating equilibrium oxalate speciation (oxalate2-, H-oxalate- and H2-oxalate) in the batch extraction solutions. Calculations were based on equilibrium pH, as measured following extraction for 24 hours.

3. Results

3.1. Sediment Characterization

The Dover sediment samples are composed of gray-colored sand with lesser quantities of slit and clay, and the content of clay increases with depth. Based on XRD, the sediment samples all have similar bulk mineralogy, with mostly quartz and small quantities of clay minerals, feldspar and mica (SM Figure S2). Bulk sediment As and Fe concentrations are between 2.4 and 12.7 mg kg-1 and between 1.77 and 5.37%, respectively, with concentrations increasing with depth (Table 1). Based on As XANES, Dover sediments contain a mixture of arsenate and arsenite with the fraction of arsenite also increasing with depth (Figure 1). Based on Fe EXAFS, Dover sediments contain mainly non-reactive Fe-containing silicates (on average, 65 mol% Fe), with lesser quantities of Fe(III) oxyhydroxides and Fe(II) carbonates and sulfides (Table 2). Overall, Dover sediments from two locations EW1 and EW8b are similar.

Table 1.

Bulk sediment As and Fe concentrations of the sediment samples used in the experiments, on a dry mass basis, as determined by XRF. All calculations of sediment As and Fe mobilization in this study are based on these concentrations. Accuracy for As and Fe on this XRF instrument are within 100 ± 6% and 100 ± 10%, respectively, based on certified NIST standards.

| Sample ID | Bulk As Conc. (mg kg-1) |

Bulk Fe Conc. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The Dover Municipal Landfill Superfund site | ||

| Dover EW1 | ||

| top | 2.6 | 1.90 |

| middle | 4.8 | 1.99 |

| bottom | 12.7 | 5.37 |

| Dover EW8b | ||

| top | 2.4 | 1.77 |

| middle | 5.8 | 3.98 |

| bottom | 8.7 | 4.73 |

| The Vineland Chemical Company Superfund site | ||

| aquifer 006 | 101 | 0.11 |

| vadose 003 | 374 | 0.46 |

Figure 1.

Normalized As XANES spectra of the sediment samples used in the experiments. The spectra are vertically offset for clarity. Reference spectra are included for comparison.

Table 2.

Iron mineral compositions of the sediment samples used in the experiments, as determined by Fe EXAFS linear combination fitting analysis. Reduced χ2 of the fits are listed for evaluating fit quality. Iron EXAFS spectra and fits are in SM Figure S3.

| Sample ID | Ferrihydrite (%) | Goethite (%) | Hematite (%) | Magnetite (%) | Siderite (%) | Mackinawite (%) | Fe-silicates (%) | Reduced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Dover Municipal Landfill Superfund site | ||||||||

| Dover EW1 | ||||||||

| top | 11 ± 9 | 3 ± 4 | 0 ± 2 | 0 ± 3 | 7 ± 4 | 3 ± 2 | 76 ± 6 | 0.48 |

| middle (a) | 41 ± 7 | 0 ± 3 | 0 ± 1 | 1 ± 2 | 9 ± 3 | 8 ± 1 | 41 ± 4 | 0.40 |

| bottom | 11 ± 4 | 10 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 5 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 70 ± 2 | 0.08 |

| Dover EW8b | ||||||||

| top | 20 ± 8 | 8 ± 3 | 0 ± 2 | 0 ± 2 | 9 ± 3 | 9 ± 1 | 54 ± 4 | 0.29 |

| middle | 9 ± 6 | 14 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 2 | 0 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | 76 ± 3 | 0.18 |

| bottom | 8 ± 5 | 17 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | 73 ± 3 | 0.10 |

| The Vineland Chemical Company Superfund site | ||||||||

| aquifer 006 | 64 ± 12 | 13 ± 5 | 8 ± 2 | 0 ± 4 | 0 ± 4 | 3 ± 2 | 12 ± 3 | 1.80 |

| vadose 003 | 50 ± 13 | 29 ± 6 | 6 ± 3 | 1 ± 4 | 4 ± 4 | 4 ± 2 | 7 ± 3 | 2.04 |

Note

According to standard-addition methods, Dover EW1 middle should contain relatively low quantity of ferrihydrite, and this difference may reflect sediment heterogeneity, variable spectral quality, or potentially measurement or fitting errors.

Vineland sediments are coarser, contain more As, and are more oxidized than Dover sediments. The orange Vineland sediments are nearly pure quartz based on XRD [20, 24]. The Vineland aquifer and vadose sediments contain 101 and 374 mg kg-1 of As and 0.11 and 0.46% of Fe, respectively (Table 1). The sediments have As present primarily (> 95%) as arsenate and Fe mineralogy dominated by Fe(III) oxyhydroxides, especially ferrihydrite (Figure 1 and Table 2).

3.2. Batch Extractions

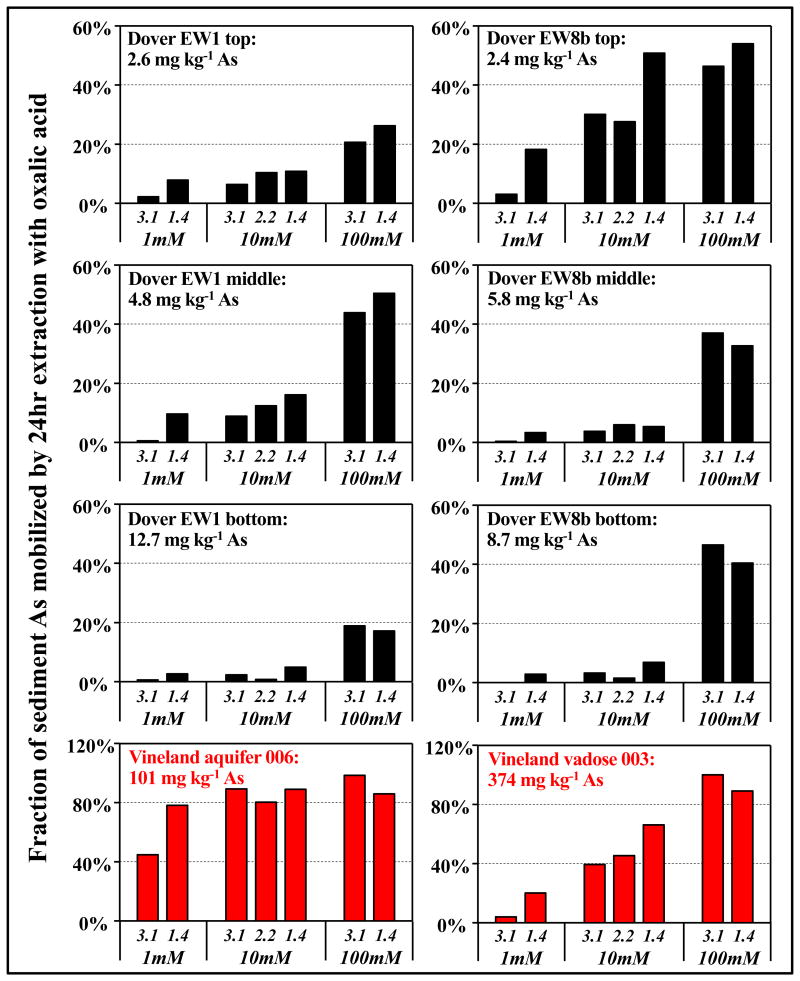

Batch extractions were conducted to examine the effectiveness of oxalic acid treatment on sediment As and Fe mobilizations. Oxalic acid mobilized significantly more As and Fe from Dover sediments than did HCl extractions at the same initial pH (SM Figure S4). This finding is consistent with results reported by Wovkulich et al. (2010), who also compared oxalic acid to other extractants including HCl [20]. In the Dover batch experiments where sediment As concentrations are found at natural background levels, there were variable As extraction efficiency rates that increased from very low (< 1%) to extensive (> 50%) of total As at higher oxalic acid concentration and lower pH (Figure 2 and SM Figure S5). In the Vineland batch experiments where there were high concentrations of ferrihydrite and sediment As, oxalic acid extractions mobilized much more As (as much as 86-100% of As from Vineland sediments at 100 mM oxalic acid), consistent with our previous study [20]. In contrast to As, Fe was extracted equally efficiently from both Vineland and Dover sediments (Figure 3). In both the Vineland and Dover batch experiments, the absolute amounts of As and Fe mobilized in the extractions ([As] and [Fe]) were linearly correlated on a log-log scale (Figure 3A). Based on the factions of As and Fe mobilized, As was mobilized preferentially over Fe (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Fractions of As mobilized in the batch extractions using different concentrations of oxalic acid (1, 10, and 100 mM) and different initial pHs (pH 3.1, 2.2, and 1.4). The initial bulk As concentrations of each sediment samples are listed on each subplot; the concentrations of oxalic acid and initial pHs are listed under each subplot.

Figure 3.

(A) Dissolved As vs Fe concentrations in the batch extractions on a log-log scale. (B) Fractions of As vs Fe mobilized from sediments in the batch extractions. The dash line represents the 1-to-1 line.

Solution pH of the oxalic acid extractions ranged between 3.1 and 1.4 initially, and rose to between 6.4 and 1.5 at the end of the batch experiment. Solution pH was buffered by mineral dissolution, and affects the mobilization of Fe in part by regulating oxalate solution speciation, i.e., the concentrations of specific oxalate species in solutions (for oxalic acid, pKa 1 = 1.2 and pKa 2 = 4.2). Comparisons of Fe mobilization and the concentration of specific protonation states of oxalate suggest that extracted [Fe] was linearly correlated with [H-oxalate-] and [H2-oxalate] on log-log scales, and that there was a stronger contribution from [H-oxalate-] to Fe mobilization relative to [H2-oxalate] (SM Figure S6). The mobilization of As was affected by oxalate solution speciation in a similar fashion (Figure 4), and the correlations between [As] and [H-oxalate-] for both Dover and Vineland batch experiments were higher than between [Fe] and [H-oxalate-] (Figure 4B vs SM Figure S6B).

Figure 4.

Dissolved As concentrations vs visual MINTEQ calculated dissolved (A) oxalate2-, (B) H-oxalate- and (C) H2-oxalate concentrations in the batch extractions on log-log scales. No linear regressions are reported on (A) because there are no significant correlations.

3.3. Column Flow-through Systems

The experiment with flow-through columns examines As and Fe mobilization under continuous flow at realistic sediment-to-solution ratios, and allows us to study readsorption and transport of the mobilized As and Fe. This study compares columns using Dover sediments with those of Vineland that have been published previously [20, 21].

3.3.1. Column with Artificial Groundwater Influent (Column A-GW)

Column A-GW is a control column that establishes a baseline of As mobilization from Dover sediments without amendment at neutral pH (Figure 5). Effluent As concentrations were low and stable, between 0.3 and 0.6 μg L-1. Effluent Fe concentrations fluctuated more than As but were also low, between 0.01 and 0.28 mg L-1. Insignificant quantities of As and Fe mobilized from Dover sediments by 40 PVs of A-GW. Therefore, any appreciable requires amendment.

Figure 5.

Results from Dover column experiments showing effluent (A) As and (B) Fe concentrations, and (C) pHs, as a function of pore volumes that had passed through the columns. On (C), the two dash lines represent the pHs of the influents.

3.3.2. Column with Oxalic Acid Influent (Column OX)

Column OX tests the effectiveness of oxalic acid as the amendment to enhance As mobilization from P&T at the Dover site (Figure 5). Effluent pHs from column OX decreased from 6.7 to 3.4 over the course of the experiment, higher than influent pH (2.2). Effluent As concentrations were below 10 μg L-1 in the first 19 PVs of 10 mM oxalic acid, but increased to above 100 μg L-1 in the next 4 PVs and then stabilized at about 180 μg L-1. Effluent Fe concentrations increased quickly after oxalic acid was introduced, from 0.1 mg L-1 to about 200 mg L-1 with 10 PVs of 10 mM oxalic acid, and then stabilized. Cumulative percentages of As and Fe mobilized from Dover sediments by 40 PVs of 10 mM oxalic acid were 25.3% and 10.6%, respectively. Previous studies [20, 21] found that 10 PVs of 10 mM oxalic acid could mobilize about 80% of As from Vineland sediments. Therefore, oxalic acid mobilized As less efficiently from Dover sediments than from Vineland sediments in the column flow-through systems, in agreement with the results from batch extractions. Oxalic acid is also known to dissolve Al (oxyhydr)oxides [9], however, Al mobilization from Dover sediments was limited (cumulative removal = 0.9%, data not shown).

3.4. Microbial Reduction within Treated and Untreated Sediments

To evaluate potential impacts from microbial reduction on residual sediment As following P&T, a series of long-term batch experiments were performed with sediments following treatment with oxalic acid, washed, and then reacted with anaerobic artificial groundwater containing dissolved organic carbon (as lactate) for 3 months. Each step of these experiments was performed anaerobically to mimic field conditions. The anaerobic oxalic acid extraction removed similar quantities of As from the sediments as the conventional extraction method (Figure 2 and SM Figure S7). The residual As concentrations in treated Dover sediments were between 0.9 and 11.8 mg kg-1; the residual As concentrations in treated Vineland aquifer and vadose sediments were 4.6 and 17.7 mg kg-1, respectively. These sediments quickly became reducing following incubation with lactate amended groundwater, releasing variable amounts of As into solution (Figure 6). In the microcosms with treated Dover sediments, dissolved As concentrations observed remained below 37 μg L-1; much lower than in microcosms with untreated Dover sediments (83 to 231 μg L-1). In the microcosms with treated Vineland aquifer and vadose sediments, dissolved As concentrations reached 478 and 2,074 μg L-1, respectively; high but much lower than untreated sediments (4,800 and 12,500 μg L1, respectively). Therefore, (i) oxalic acid treatment lowered the resulting aqueous As concentration during the reduction phase; and (ii) less As was released from Dover sediments than Vineland sediments during reduction.

Figure 6.

Dissolved As concentrations from the microcosms as a function of time, with (Left) oxalic acid treated and (Right) untreated sediments in parallel. Dissolved As concentrations for the Dover microcosms are scaled between 0 and 250 μg L-1, whereas those for the Vineland microcosms are scaled between 0 and 15,000 μg L-1.

4. Discussion

To properly assess the potential of oxalic acid amendments as a means of remediating As-contaminated aquifers, there are several practical matters that should be addressed. First, the extraction should be efficient at mobilizing As from aquifer matrix. Second, since extractions seldom remove sediment As completely, the residual As in the sediments should not be released into surrounding groundwater under aquifer conditions. These experiments allow us to evaluate both.

4.1. Effectiveness of Oxalic Acid on Arsenic Mobilization

As a relatively strong organic acid, the addition of oxalic acid decreases sediment pH. The lowered pH can potentially lead to the dissolution of some As-bearing minerals and also direct desorption of As, in particular, arsenite [30]. Comparison between oxalic acid extractions and HCl extractions (SM Figure S4) [20], however, indicates that the enhanced As mobilization by oxalic acid is not solely due to the lowered pH but also due to the presence of oxalate. Iron (oxyhydr)oxides are often the dominant sorbents for As and other metal(loid)s and nutrients in the natural environments. The use of oxalic acid mobilizes As from sediments by effectively dissolving As-bearing Fe (oxyhydr)oxides [15, 16], such as ferrihydrite:

| (1) |

The dissolution of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides also mobilizes many other ions, such as phosphate, sulfate and carbonate, which compete with As for remaining sorption sites and mobilize additional As. The relationship between Fe (oxyhydr)oxide dissolution and As mobilization is confirmed by the correlation between dissolved Fe and As concentrations in the oxalic acid batch experiments (Figure 3A). However, the fraction of As mobilized from sediments was much higher than Fe in the batch experiments (Figure 3B). This is in part because oxalate species can also adsorb on minerals and mobilize As by competitive desorption [12, 14, 17]:

| (2) |

Such competitive desorption from oxalate species can sometimes play a more significant role in As mobilization than mineral dissolution [13].

Both dissolution of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides and competitive desorption by the use of oxalic acid (Reactions 1 and 2) are affected by oxalate solution speciation (oxalate2-, H-oxalate- and H2-oxalate), and thus are pH-dependent. Dissolution of Fe (oxyhydr)oxides by oxalic acid is found to be optimal at pH 2-3 where H-oxalate- is the dominant oxalate species [15, 16, 21]. Better correlations between [As] and [H-oxalate] than those between [Fe] and [H-oxalate-] (Figure 4B vs SM Figure S6B), suggest that competitive desorption might also be more extensive when H-oxalate- dominates. The pH of the oxalic acid extractant, if injected into aquifer systems, would change due to the reactions occurred, especially mineral dissolution, the pH buffering effects from natural circumneutral sediments and groundwater, concentration fluctuations and dilution in aquifers, and potentially other factors. When using oxalic acid based P&T for remediating As-contaminated aquifers, this pH change has to be considered to ensure optimal removal rates of sediment As. The extents of Fe mobilization were similar in Dover and Vineland sediments (Figure 3), as were the pH changes that resulted from reaction. Despite these similarities, significantly lower fractions of As were mobilized from Dover sediments relative to Vineland sediments. This difference can partially be explained by contrasting mineralogy — Dover sediments are mineralogically diverse and thus contain some As host minerals that cannot be efficiently dissolved by oxalic acid, such as As bound within or protected by silicate minerals and/or relatively crystalline Al (oxyhydr)oxides. This occluded As is also not susceptible to extraction by competitive sorption. Dover sediments have significantly lower As concentrations than Vineland sediments (Table 1), and the resulting lower surface coverages should make them less susceptible to competition with oxalate. Dover sediments also contain significant arsenite (Figure 1), which is mobilized less efficiently by oxalate than is arsenate [31]. Therefore, when using enhance P&T for the real world As remediation, the reactivities of the As-bearing substances in aquifer sediments, as well as the concentration and redox states of sediment As, are all important factors in evaluating the potential of oxalic acid based extractions.

Comparing the release of Fe and As from column experiments provides insight into the As release mechanisms. The mobilization of Fe precedes the mobilization of As in the oxalic acid treated Dover column (Figure 5A vs 5B), whereas the order of mobilization is the opposite in the oxalic acid treated Vineland columns [20, 21]. We hypothesize that this difference is due to the more extensive adsorption or precipitation of Fe in the more oxic Vineland columns than the anaerobic Dover columns [20, 21]. More importantly, Dover sediments have low As-to-Fe ratios and adequate sorption sites, which allows As (re)adsorption as the mobilized As transports from the column inlet to the outlet. The lag between oxalic acid addition and As mobilization in the Dover column implies that, if applied to the P&T system at the Dover site, the effect from oxalic acid on mobilizing As may not be immediately seen. For our experiments using complex natural sediments, a well-defined budget of As mass flux is difficult to generate (e.g., how much As mobilization by oxalic acid resulted from mineral dissolution, how much resulted from competitive desorption, and how much As readsorption occurred). Reactive transport modeling can be helpful in this regard and is an ongoing effort. Nevertheless, it is clear from the experimental data that the addition of oxalic acid will mobilize significantly more As than groundwater alone.

4.2. Reactivity of Residual Sediment Arsenic towards Reduction

Microbial reduction of As-bearing Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides is one of the principal pathways responsible for elevated groundwater As concentrations [4, 5, 25, 26, 32, 33]. Microbial reduction is an important process causing As release at the anaerobic Dover landfill, which contains abundant organic matter, and, to some extent, at the Vineland site, where conditions are variable but often suboxic. In lactate-amended microcosms, reducing conditions were highly effective at releasing sediment As into solution, even in most sediments previously reacted with oxalic acid (Figure 6). This indicates that, unless removed completely, residual sediment As could still serve as a potential source of groundwater As contamination. Nevertheless, for both the Dover and Vineland microcosms, dissolved As concentrations in the ones with oxalic acid treated sediments were one order of magnitude lower than those with untreated sediments. Therefore, the sediments after oxalic acid treatment are significantly less vulnerable to microbial reduction than without oxalic acid. Under field conditions the aquifers may not be exposed to such extensive and rapid reduction, potentially causing less As mobilization than was observed in these microcosms. However, it is clear that the oxalic acid treated Vineland sediments released much more As into solutions under reducing conditions than the treated Dover sediments, even though their residual sediment As concentrations were similar (Figure 6). We attribute the difference to their difference in sediment Fe mineralogy. Dover sediments contain little reactive Fe(III) oxyhydroxides (Table 2), which can be dissolved more completely by oxalic acid. Vineland sediments, on the other hand, are dominated by amorphous ferrihydrite which is the most bioavailable Fe mineral for dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacteria [32, 33]. Although ferrihydrite should be dissolved preferentially when treated with oxalic acid, there are still substantial quantities of ferrihydrite that persist after oxalic acid extraction, as observed repeatedly in this study and our previous studies [20-22]. These remaining reactive Fe(III) minerals make the sediments more susceptible to microbial reduction and the liberation of more As into solution. This indicates that sediment Fe mineralogy needs to be carefully evaluated to understand the long-term effectiveness of such oxalic acid enhanced P&T on groundwater As remediation.

4.3. Implications for Groundwater Arsenic Remediation

The Dover and Vineland Superfund sites selected in this study are in many ways typical of many As-contaminated sites. They all have similar aquifer geochemical characteristics including As-bearing Fe minerals that are susceptible to reductive dissolution, and carbonate-buffered groundwater containing variable concentrations of dissolved Fe. The Dover and Vineland sites span a range of sediment As concentrations and redox states, from natural abundance As and reducing conditions at Dover to anthropogenically-contaminated and more oxic at Vineland. Therefore, the findings in this study may be applicable to P&T remediation technology at many systems. This study suggests that oxalic acid could mobilize As from both Dover and Vineland sediments, and probably many other environments, as long as pH can be controlled during injection. Residual As in oxalic acid treated sediments also appears to be significantly less labile. These factors suggest that oxalic acid extractions may be effective in field settings as a means of removing As, and decreasing solute concentrations. Although more research would be required to best determine how to implement such an extraction in the field, oxalic acid extractions used in combination with P&T as part of the clean-up activities, could improve remediation efficiency and decrease the cumulative operation time and cost. This study suggests that complete As extraction may be difficult to achieve, but also that it may not be required for the treatment method to useful. It also suggests that the efficacy of P&T must consider sediment Fe mineralogy and the potential for a site to stay or become reducing when evaluating its overall potential as a groundwater remediation strategy. Extraction could be optimized by using higher oxalic acid strength, maintaining pH of the aquifer at 2-3 during operation, allowing longer P&T operation time or flow rates, and combining additional amendment(s). At sites with limited quantities of reactive Fe(III) minerals or sites that have little chance of becoming highly reducing, residual sediment As after oxalic acid treatment would not be easily mobilized, and thus groundwater As remediation via enhanced P&T would be promising.

Supplementary Material

Figures S1 – S7. The supplementary figures contain digital pictures showing column set-up, sediment XRD spectra, Fe EXAFS spectra and fits, and additional data for the batch extractions.

Highlights.

Arsenic mobilization from aquifer sediments by oxalic acid addition was examined.

Sediments from two distinct As-contaminated U.S. Superfund sites are studied.

Oxalic acid is a promising amendment for enhanced pump-and-treat at both sites.

Residual sediment As after treatment is less vulnerable to microbial reduction.

Iron mineralogy controls the reactivity of residual sediment As after treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grants ES010349 and ES009089). Some of the analyses were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a national user facility operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy. The authors are grateful to D. Peschel, M. Webster and D. Luce for access to the Dover Municipal Landfill Superfund site. The authors also would like to thank R. Davis for technical support during XAS analysis, and T. Kenna for help with XRD analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.U.S. EPA. Arsenic treatment technologies for soil, waste, and water. 2002 http://www.clu-in.org/download/remed/542r02004/arsenic_report.pdf.

- 2.Smedley PL, Kinniburgh DG. A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Appl Geochem. 2002;17:517–568. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Couture RM, Van Cappellen P. Reassessing the role of sulfur geochemistry on arsenic speciation in reducing environments. J Hazard Mater. 2011;189:647–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.deLemos JL, Bostick BC, Renshaw CE, Sturup S, Feng XH. Landfill-stimulated iron reduction and arsenic release at the Coakley Superfund Site (NH) Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:67–73. doi: 10.1021/es051054h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keimowitz AR, Simpson HJ, Stute M, Datta S, Chillrud SN, Ross J, Tsang M. Naturally occurring arsenic: Mobilization at a landfill in Maine and implications for remediation. Appl Geochem. 2005;20:1985–2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leist M, Casey RJ, Caridi D. The management of arsenic wastes: problems and prospects. J Hazard Mater. 2000;76:125–138. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3894(00)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. EPA. Improving Nationwide Effectiveness of Pump-and-Treat Remedies Requires Sustained and Focused Action to Realize Benefits Report. EPA Office of Inspector General, Memorandum Report 2003-P-000006. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. EPA. Treatment Technologies for Site Cleanup: Annual Status Report. (Twelfth) 2007 http://epa.gov/tio/download/remed/asr/12/asr12_full_document.pdf.

- 9.van Hees PAW, Lundstrom US, Giesler R. Low molecular weight organic acids and their Al-complexes in soil solution - composition, distribution and seasonal variation in three podzolized soils. Geoderma. 2000;94:173–200. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox TR, Comerford NB. Low-Molecular-Weight Organic-Acids in Selected Forest Soils of the Southeastern USA. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1990;54:1139–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reichard P, Kretzschmar R, Kraemer S. Dissolution mechanisms of goethite in the presence of siderophores and organic acids. Geochim Cosmochim Ac. 2007;71:5635–5650. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu B, Jia SY, Liu Y, Wu SH, Han X. Mobilization and re-adsorption of arsenate on ferrihydrite and hematite in the presence of oxalate. J Hazard Mater. 2013;262:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi R, Jia YF, Wang CZ, Yao SH. Mechanism of arsenate mobilization from goethite by aliphatic carboxylic acid. J Hazard Mater. 2009;163:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohapatra D, Singh P, Zhang W, Pullammanappallil P. The effect of citrate, oxalate, acetate, silicate and phosphate on stability of synthetic arsenic-loaded ferrihydrite and Al-ferrihydrite. J Hazard Mater. 2005;124:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panias D, Taxiarchou M, Paspaliaris I, Kontopoulos A. Mechanisms of dissolution of iron oxides in aqueous oxalic acid solutions. Hydrometallurgy. 1996;42:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SO, Tran T, Jung BH, Kim SJ, Kim MJ. Dissolution of iron oxide using oxalic acid. Hydrometallurgy. 2007;87:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer M, Blodau C. Mobilization of arsenic by dissolved organic matter from iron oxides, soils and sediments. Sci Total Environ. 2006;354:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim EJ, Baek K. Enhanced reductive extraction of arsenic from contaminated soils by a combination of dithionite and oxalate. J Hazard Mater. 2015;284:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim EJ, Lee JC, Baek K. Abiotic reductive extraction of arsenic from contaminated soils enhanced by complexation: Arsenic extraction by reducing agents and combination of reducing and chelating agents. J Hazard Mater. 2015;283:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wovkulich K, Mailloux BJ, Lacko A, Keimowitz AR, Stute M, Simpson HJ, Chillrud SN. Chemical treatments for mobilizing arsenic from contaminated aquifer solids to accelerate remediation. Appl Geochem. 2010;25:1500–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wovkulich K, Mailloux BJ, Bostick BC, Dong HL, Bishop ME, Chillrud SN. Use of microfocused X-ray techniques to investigate the mobilization of arsenic by oxalic acid. Geochim Cosmochim Ac. 2012;91:254–270. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wovkulich K, Stute M, Mailloux BJ, Keimowitz AR, Ross J, Bostick B, Sun J, Chillrud SN. In situ oxalic acid injection to accelerate arsenic remediation at a superfund site in New Jersey. Environ Chem. 2014;11:525–537. doi: 10.1071/EN13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. EPA. Final source control remedial action work plan, Dover Municipal Landfill Superfund Site. 2011 http://www.epa.gov/region1/superfund/sites/dover/481851.pdf.

- 24.Sun J, Chillrud SN, Mailloux BJ, Stute M, Singh R, Dong H, Lepre CJ, Bostick BC. Enhanced and Stabilized Arsenic Retention in Microcosms through the Oxidation of Ferrous Iron by Nitrate. Chemosphere. 2016;144:1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benner SG, Hansel CM, Wielinga BW, Barber TM, Fendorf S. Reductive dissolution and biomineralization of iron hydroxide under dynamic flow conditions. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:1705–1711. doi: 10.1021/es0156441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saalfield SL, Bostick BC. Changes in Iron, Sulfur, and Arsenic Speciation Associated with Bacterial Sulfate Reduction in Ferrihydrite-Rich Systems. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:8787–8793. doi: 10.1021/es901651k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webb SM. SIXpack: a graphical user interface for XAS analysis using IFEFFIT. Physica Scripta. 2005;T115:1011–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun J, Mailloux BJ, Chillrud SN, van Geen A, Bostick BC. Quantifying Ferrihydrite in Sediments by the Method of Standard-Additions Using EXAFS Spectroscopy. Analytical Chemistry. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.11.021. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gustafsson JP. Visual MINTEQ 3.0 user guide. Dep. of Land and Water Resour. Eng., KTH Royal Inst of Technol.; Stockholm, Sweden: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixit S, Hering JG. Comparison of arsenic(V) and arsenic(III) sorption onto iron oxide minerals: Implications for arsenic mobility. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:4182–4189. doi: 10.1021/es030309t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tao YQ, Zhang SZ, Jian W, Yuan CG, Shan XQ. Effects of oxalate and phosphate on the release of arsenic from contaminated soils and arsenic accumulation in wheat. Chemosphere. 2006;65:1281–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postma D, Jessen S, Nguyen TMH, Mai TD, Koch CB, Pham HV, Pham QN, Larsen F. Mobilization of arsenic and iron from Red River floodplain sediments. Vietnam, Geochim Cosmochim Ac. 2010;74:3367–3381. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansel CM, Benner SG, Fendorf S. Competing Fe(II)-induced mineralization pathways of ferrihydrite. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:7147–7153. doi: 10.1021/es050666z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1 – S7. The supplementary figures contain digital pictures showing column set-up, sediment XRD spectra, Fe EXAFS spectra and fits, and additional data for the batch extractions.