Abstract

The objective of this study was to estimate solid cancer risk attributable to long-term, fractionated occupational exposure to low-doses of ionizing radiation. Based on cancer incidence for the period 1950–1995 in a cohort of 27,011 Chinese medical diagnostic X-ray workers and a comparison cohort of 25,782 Chinese physicians who did not use X-ray equipment in their work, we used Poisson regression to fit excess relative risk (ERR) and excess absolute risk (EAR) dose-response models for incidence of all solid cancers combined. Radiation dose reconstruction was based on a previously published method that relied on simulating measurements for multiple X-ray machines, workplaces and working conditions, information about protective measures, including use of lead aprons, and work histories. The resulting model was used to estimate calendar year-specific badge dose calibrated as personal dose equivalent (Sv). To obtain calendar year-specific colon doses (Gy), we applied a standard organ conversion factor. 1643 cases of solid cancer were identified in 1.45 million person-years of follow-up. In both ERR and EAR models, a statistically significant radiation dose-response relationship was observed for solid cancers as a group. Averaged over both sexes, and using colon dose as the dose metric, the estimated ERR/Gy was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.48, 1.45), and the EAR was 22 per 104PY-Gy (95% CI: 14, 32) at age 50. We obtained estimates of the ERR and EAR of solid cancers per unit dose that are compatible with those derived from other populations chronically exposed to low dose-rate occupational or environmental radiation.

Keywords: Medical X-ray workers, solid cancer, ionizing radiation, occupational exposure, epidemiology, China

INTRODUCTION

Understanding cancer risks associated with long-term fractionated or protracted exposure to low doses of ionizing radiation is an important aim for radiation protection policy; yet, most quantitative estimates of the carcinogenic hazards of ionizing radiation are based on the experience of persons who received large doses of radiation within a short time period. These include studies of survivors of the atomic bomb explosions in Japan and people irradiated for a variety of medical reasons [1–3]. The applicability of these data in assessing cancer risks in persons who experience prolonged or repeated exposure to low-level ionizing radiation, such as occurs in certain occupations, following environmental releases, and from multiple medical diagnostic procedures, is uncertain. Long-term studies of large, occupationally or environmentally exposed populations that include radiation dose estimates for individuals are few but include studies of cancer risk among radiation workers in the nuclear industry [4–6], the UK National Registry for Radiation Workers (NRRW) study [7], and the Techa River study of effects of chronic low dose-rate exposure to the general population due to environmental radiation releases associated with the Soviet nuclear weapons program [8].

The Chinese medical X-ray worker (CMXW) study [9–12] is another such study. First organized in 1981, it has undergone noteworthy enhancements in recent years that increase its utility for radiation risk assessment. The study includes 27,011 medical X-ray workers (radiologists and radiologic technicians) who were employed between January 1st, 1950 and December 31th, 1980 at major hospitals in 24 provinces of China. The median duration of work was 26 years. In addition, there is a comparison population consisting of 25,782 surgeons, otolaryngologists and other physicians who did not use X-ray equipment in their work and who worked in the same hospitals during the same period. The first follow-up was conducted in 1980 [9], with additional follow-ups in 1985, 1990, and 1995. Follow-up of this cohort ceased at the end of 1995 [12]. In previous analyses, we found statistically significant elevated risks for leukemia and solid cancers (including cancers of the skin, female breast, esophagus, liver, lung and bladder) among the Chinese medical X-ray workers relative to the comparison cohort [12]. Patterns of risk by calendar year of initial employment and number of years since initial employment suggested that radiation may have contributed to the excess risk of leukemia, skin cancer, cancer of the female breast and, possibly, thyroid cancer, whereas an important role of non-radiation factors was suggested for cancers of the lung, liver and esophagus [12]. An important limitation of these studies was the unavailability of radiation dose estimates for individual X-ray workers, as personal dose monitoring did not begin until 1985. A dose reconstruction study, which was designed specifically for this cohort, reported average annual estimated dose from 1949 through 1995 [12–15]. In the present study, we use these reconstructed dose estimates to obtain estimates of cumulative colon doses for all individuals in the cohort and to estimate solid cancer risks associated with those doses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population, follow-up, and ascertainment of incident cancers

Detailed information on characteristics of the study population and survey methods were given in earlier papers [9–12]. Workers in the different hospital departments were identified from hospital administrative records. Numbers of Chinese medical X-ray workers enrolled in the cohort are listed in Table 1 by initial year of employment and sex. While cancer follow-up began in 1950, some workers were first employed before 1950. Eighty per cent of the X-ray worker population is male, and 62% began work in 1970 or later. There were relatively more females in the comparison group (31%). Mean age at entry was 26.4 years (y) for X-ray workers and 25.1 y for the comparison group. Ninety-five per cent of cohort members were still alive at the end of 1995. X-ray workers were followed for a total of 683,398 person-years (PY) (mean, 25.7 y) and the comparison group for a total of 762,949 PY (mean, 29.6 y). [Table 1 here]

Table 1.

Number of cohort members initially enrolled in the Chinese medical X-ray workers study, and percentages of those still alive as of December 31, 1995, by group, initial year of employment and sex

| Group | Initial Year of Employment | Male | Female | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| No. of people | % Alive a | No. of people | % Alive a | No. of people | % Alive a | ||

| X-ray | −1949 | 400 | 72 | 63 | 87 | 463 | 74 |

| 1950–1954 | 1626 | 84 | 377 | 89 | 2003 | 85 | |

| 1955–1959 | 1883 | 88 | 603 | 94 | 2486 | 89 | |

| 1960–1964 | 2396 | 92 | 868 | 94 | 3264 | 93 | |

| 1965–1969 | 1551 | 95 | 439 | 96 | 1990 | 96 | |

| 1970–1974 | 5652 | 97 | 1258 | 97 | 6910 | 97 | |

| 1975–1980 | 8063 | 98 | 1832 | 98 | 9895 | 98 | |

| Sub-total | 21 571 | 95 | 5440 | 96 | 27 011 | 95 | |

|

| |||||||

| Comparison | −1980 | 17 694 | 93 | 8088 | 96 | 25 782 | 94 |

|

| |||||||

| Total | −1980 | 39 265 | 94 | 13 528 | 96 | 52 793 | 95 |

As of December 31, 1995.

Cancer case information for cancers occurring through 1995, including date, diagnosis and details related to diagnosis, was obtained from medical records as described in previous papers [9–12]. Histological confirmation was available for 70% of all cancer cases; most other cancer diagnoses were based on radiological examinations. All neoplasms exclusive of leukemia were included. The 9th revision of the International Classification on Diseases (ICD9) was used to code neoplasm diagnoses (ICD9 140–239, exclusive of 204–207).

Radiation dose reconstruction

The only relevant occupational radiation exposures for most, if not all, members of this cohort of medical diagnostic X-ray workers are from (25–40 keV X-rays), with no or negligible exposure to neutrons or internally deposited radionuclides.

Reconstructed dose estimates are based on a previously published method that relied on simulating measurements for multiple X-ray machines, workplaces and working conditions, information about protective measures including use of lead aprons, and work histories for 3805 (14.1%) of the workers [12–15]. The resulting mathematical model provided an estimate of calendar year-specific badge dose calibrated as personal dose equivalent (Sv) at a tissue depth of 10 mm, HP (10). Estimates of average annual dose from 1950 to 1995 were reported in earlier papers [12–14] and are included in the present analyses. These dose data are in the form of a step function of mean dose with respect to five-year intervals of calendar year of employment. For calendar years before 1949, we assumed that doses were equal to the average dose for 1949. We smoothed the data by assuming that the logarithm of dose was a linear function of the corresponding calendar year to obtain calendar year-specific HP (10) dose (Supplemental Figure 1). We assumed that each member of the cohort received that calendar year-specific dose if he or she worked that year. [Available individualized data for the entire cohort are year started work and year stopped work; the more detailed work history information is available only for the 14% sample.]

We estimated colon dose as an approximate proxy for dose to all organs giving rise to solid cancers. In order to obtain colon dose from HP (10), we employed formula (1).

| (1) |

The parameter Dcolon/Ka denotes colon absorbed dose per unit air kerma; it pertains to mono-energetic photons incident in various incident geometries on an adult anthropomorphic computational model. The parameter HP (10)/Ka denotes conversion coefficients from kerma free-in-air to HP (10). Both Dcolon/Ka and HP (10)/Ka were obtained from International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) Publication 74 [16]. The Chinese medical X-ray workers were primarily exposed to photon radiation (X-rays in the energy range 25–40 keV). We chose parameters of 35 keV and antero-posterior (AP) geometry, the irradiation geometry in which the ionizing radiation is incident on the front of the body in a direction orthogonal to the long axis of the body, in accordance with data from reference [13]. We estimated Dcolon/Ka and HP (10)/Ka at 35 keV as arithmetic means of corresponding values for 30 and 40 keV [13]. We used a conversion coefficient from badge dose [HP (10)] to colon dose of 0.3505 [= (Dcolon ÷ HP (10)]. In combination with information about specific calendar years worked, we calculated estimates of cumulative colon dose for individual medical X-ray workers.

Dosimetry validation studies using biological markers were described previously for this study population [17, 18]. In a study of chromosomal rearrangements in 84 medical X-ray workers and 17 non-X-ray workers, Wang et al. [18] found translocation frequencies (per cell) of 0.0212, 0.0181 and 0.0075 among X-ray workers who began work before 1960, during 1960–1969, and after 1970, respectively. Among non-X-ray workers, the frequency was 0.0056/cell. When a previously published calibration function based on in vitro experiments was applied to the translocation frequency data [19], average dose estimates by calendar year of entry were very similar for physical and biological doses (Table 3 from Wang et al. [18]).

Table 3.

Fitted models for estimating excess relative risk (ERR) of solid cancers per Gy of radiation for different study populationsa

| Studies b | Dose in risk models | No. of cancer cases | ERR/Gy (95% CI)

|

Age at exposure (95% CI), χf | Attained age (95% CI), γg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Female | Sex-averaged | |||||

|

Incidence

Studies

| |||||||

| CMXW c | 5 years lagged colon dose | 1,643a | 0.82* (0.46,1.32) | 0.93* (0.35,1.84) | 0.87* (0.48, 1.45) | NA | 6.99* (5.56,8.54) |

| CMXW c | 5 years lagged badge dose | 1,643a | 0.29* (0.16,0.46) | 0.32* (0.12,0.64) | 0.30* (0.17,0.51) | NA | 6.99* (5.56,8.54) |

| LSS d | 5 years lagged colon dose | 17,448 | 0.35 (0.28,0.43)e | 0.58 (0.43,0.69)e | 0.47 (0.40,0.54)e | −0.17 (−0.25,−0.07) | −1.65 (−2.1,−1.2) |

| 3rd NRRW | 10 years lagged badge dose | 10,855a | NA | NA | 0.27 (0.04,0.51)e | NA | NA |

| Techa River | 5 years lagged stomach dose | 1,933 | NA | NA | 0.8 (0.1,1.5) | NA | NA |

| BNFL | 10 years lagged badge dose | 2,535 | NA | NA | 0.87 (0.36,1.44)e | NA | NA |

|

| |||||||

|

Mortality

Studies

| |||||||

| INWORKS | 10 years lagged colon dose | 19,064a | NA | NA | 0.48 (0.20,0.79) e | NA | NA |

| 3rd NRRW | 10 years lagged badge dose | 6,959a | NA | NA | 0.28 (0.02,0.56) e | NA | NA |

| BNFL | 10 years lagged badge dose | 1,363 | NA | NA | 1.03 (0.37,1.81) e | NA | NA |

All cancers exclusive of leukemia.

CMXW= Chinese medical X-ray workers study; LSS=Life Span Study [2]; NRRW=National Registry for Radiation Workers study [7], both have incidence data and mortality data; Techa River study [8], external and internal exposure; estimate is adjusted for smoking; BNFL= British Nuclear Fuels plc study [4], we cited external radiation workers only. INWORKS [6] nuclear industry workers from France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, cancer mortality. The LSS shows results for acute exposure. All other studies are for chronic exposure. All studies show risks for external exposure, but the Techa River study includes both for external and internal radiation exposures.

At attained age 50.

At attained age 70 after exposure at age 30.

90% CI.

Per-decade increase in age at exposure over the range 0–30years (χ).

Exponent of attained age (γ).

P<0.02

Statistical methods

The relative and absolute risk models used here are based on those used in the Life Span Study (LSS) of Japanese atomic bomb survivors published by the U.S. National Research Council’s BEIR VII Committee [20].

Using the DATAB module of the Epicure software package [21, 22], we stratified person-time and solid cancer incidence data by group (X-ray workers or comparison cohort), 5-year lagged cumulative radiation dose (4 categories), gender, birth year (6 categories: every decade from 1910 to 1950, years before 1910, and years after 1950), initial year of employment (6 categories: before 1950, plus every 5 years from 1950 to 1975), age started work (10 categories: from 20 to 60 years by 5 year intervals, plus ages lower than 20 and ages higher than 60), attained age (11 categories: from 40 to 85 years by 5 year intervals, plus ages lower than 40, and ages higher than 85) and attained calendar time (9 categories: Jan 1, 1910 to Dec 31, 1954 is group 1 with 45 years; Jan 1, 1955 to Dec 31, 1989 by 5 year intervals; and Jan 1, 1990 to Jan 1, 1996).

The basic model for the excess relative risk (ERR) was set as:

| (2) |

where s represents gender, b represents birth year, a represents attained age and d represents dose (in Gy). The first three variables were modeled as determinants of baseline rates λ0; s and a also were included as potential modifiers of the ERR term, ρs (d)*ε (z). The ERR was gender-specific and was set as the product of a linear dose-response function, ρs(d), and its modification factors z, including sex, age at first exposure and attained age.

We also fit an excess absolute risk (EAR) model. It was set as:

| (3) |

with the notation being the same as in the ERR model. The EAR was gender-specific and was set as the product of a linear dose-response function, ρs(d), and its modification factors z, as in the ERR model.

We used Poisson regression maximum likelihood analyses to obtain parameter estimates, and we computed two-sided likelihood-based confidence bounds for the parameters in the fitted models. The AMFIT module of the Epicure software package [21, 22] was used to fit the risk models.

RESULTS

Radiation dose

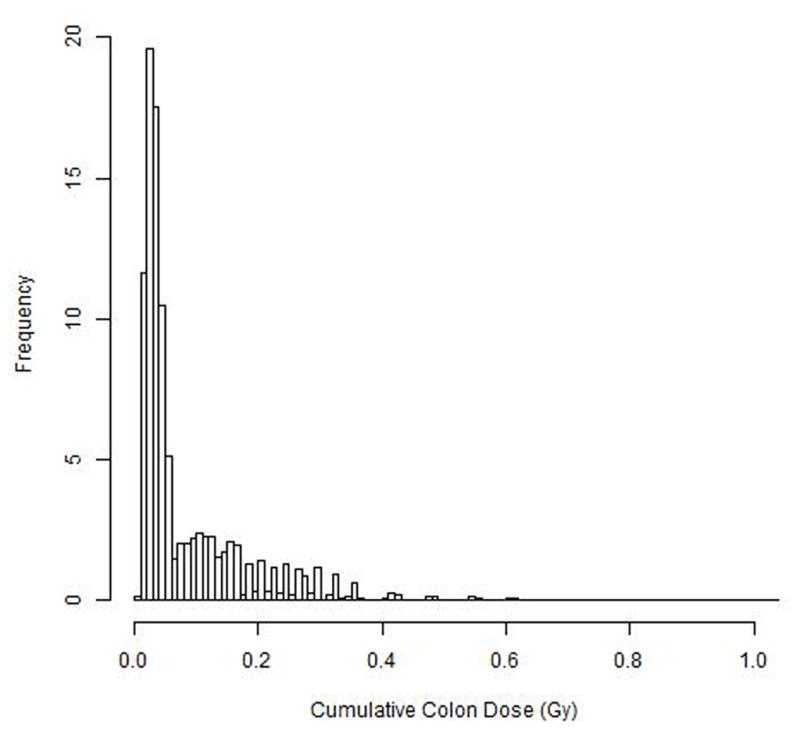

The smoothed HP (10) dose (external dose) decreased over calendar time, and the decline was steeper during the earlier years (1950–70) than in more recent years [Supplemental Figure 1]. The mean reconstructed badge dose was 0.25 Gy (median, 0.12 Gy). The distribution of cumulative colon dose also was very left-skewed (Figure 1): about 60% of medical X-ray workers had colon doses lower than 0.05 Gy and less than 1% had doses greater than 0.5 Gy. The mean cumulative colon dose was 0.086 Gy (median, 0.042 Gy). Based on personal annual colon dose, we obtained average cumulative colon dose by initial year of employment group (Table 2a). Medical X-ray workers who began work in 1949 or earlier had a mean colon dose of 0.583 Gy, while those who began work in 1975 or later had a mean dose of 0.024 Gy. [Figure 1, Table 2b].

Figure 1.

Table 2.

Distribution of person-years and cancer cases by initial year of employment (2a) and colon dose (2b)

| Table 2a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Initial year of employment | Colon dose, Gy (Mean) | Colon dose, Gy (Median) | PYR | CASES |

| X-ray | ≥ 1970 | 0.031 | 0.029 | 328,856 | 233 |

| 1965–1969 | 0.07 | 0.071 | 54,824 | 57 | |

| 1960–1964 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 105,624 | 137 | |

| ≤ 1959 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 194,121 | 368 | |

| Sub-total | 0.086 | 0.042 | 683,425 | 795 | |

|

| |||||

| Comparison | total | 0 | 0 | 762,950 | 848 |

| Table 2b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Colon dose (Gy) Range | Colon dose (Gy) Mean | Colon dose (Gy) Median | PYR | CASES |

| X-ray | 0–<0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 241,390 | 187 |

| 0.04–<0.12 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 201,523 | 206 | |

| 0.12–<0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 30,213 | 57 | |

| 0.14–2 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 210,299 | 345 | |

| Sub-total | 0.086 | 0.042 | 683,425 | 795 | |

|

| |||||

| Comparison | total | 0 | 0 | 762,950 | 848 |

Cancer incidence

Among these 52,793 workers followed for cancer incidence from 1950 to 1995, 1643 solid cancer cases were ascertained, including 795 in the exposed cohort and 848 in the reference cohort. The six most common types of solid cancer were cancers of the lung (316 cases), liver (298 cases), stomach (215 cases), lip, oral cavity and pharynx (119 cases), rectum (102 cases) and female breast (100 cases). Three benign neoplasms occurred among the X-ray workers.

Risk models and coefficients

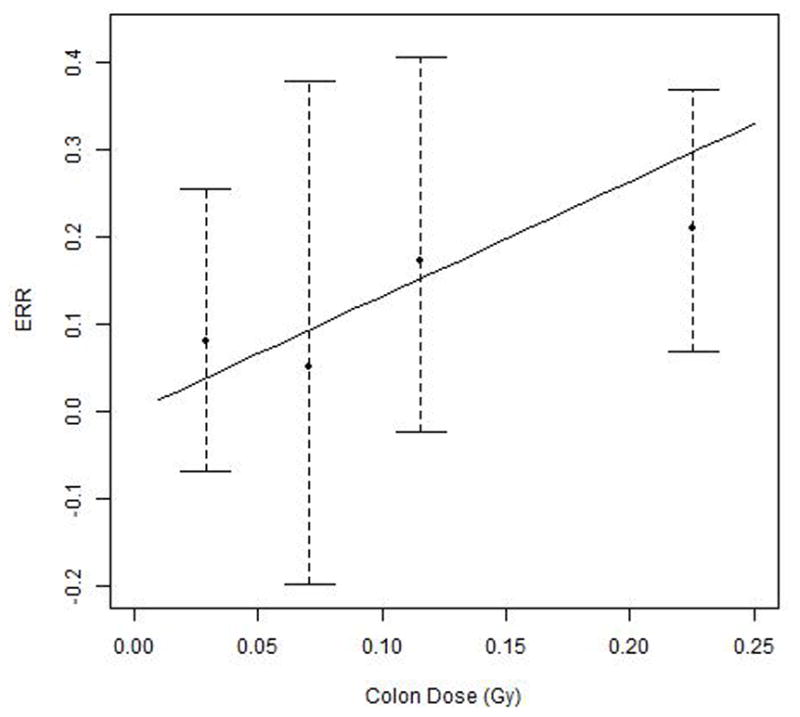

Both the ERR model and the EAR model for incidence of all solid cancers combined showed a statistically significant dose-response (colon dose), with P=0.002 and P<0.001, respectively. Among modification factors considered in the risk models, gender and attained age showed effects on the ERR/Gy (P<0.05 and P<0.001, respectively) and EAR/104 PY-Gy (P<0.05 and P<0.001, respectively). Estimates of regression coefficients for variables in the linear ERR and EAR models are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The estimated ERR/Gy at age 50 and averaged across both sexes was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.48, 1.45). The fitted ERR and its 95% bounds as a function of colon dose are shown in Figure 2; the individual data points shown represent non-parametric estimates of ERRs by dose categories. Averaged over both sexes, the EAR was 22 per 104 PY-Gy (95% CI: 14, 32) for an attained age of 50 years. The corresponding estimates in terms of reconstructed badge dose, rather than colon dose, are 0.30/Gy (95% CI: 0.17, 0.51) for the ERR and 8 per 104 PY-Gy (95% CI: 5, 11) for the EAR.

Table 4.

Fitted models for estimating excess absolute risk (EAR) of incident solid cancers per 104 person-years per Gy of radiationa

| Study | EAR/104 PY-Gy

(95% CI) |

Per-Decade Increase in Age at Exposure (95% CI), χe | Exponent of Attained age (95% CI), γf | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Female | Sex-averaged | |||

| CMXW b (colon dose) | 25 (16,36) | 18 (8,33) | 22 (14,32) | No indication of effect modification | 5.7 (4.6,7.0) |

| CMXW b (badge dose) | 9 (6,13) | 6 (3,12) | 8 (5,11) | No indication of effect modification | 5.7 (4.6,7.0) |

| LSS c | 43 (33,55)d | 60 (51,69) d | 52 (43,60) d | −0.24 (−0.32,−0.16) d | 2.38 (1.9,2.8) d |

All cancers excluding leukemia. (ICD 9 codes: 140–239, excluding 204–207).

At attained age 50.

At attained age 70, for exposure at age 30+.

90%CI

Per-decade increase in age at exposure over the range 0–30years (χ).

Exponent of attained age (γ).

Figure 2.

Lung and liver cancer were the two most common types of cancer among the X-ray workers. Because observed excesses of lung and liver cancers among X-ray workers may be related, to some extent, to factors other than radiation, we also estimated the ERR for all solid cancers exclusive of lung and liver. We found that risks of all solid cancer with and without lung and liver cancer included were very similar; the ERRs/Gy at age 50 years were 0.87 and 0.85, respectively.

In an analysis restricted to the exposed workers, the ERR/Gy increased from 0.87 to 2.0/Gy (95% CI: 1.1, 3.6). The EAR per 104 PY-Gy increased from 22 to 32 (95% CI: 21, 46). The parameter for attained age increased from 6.99 to 8.32 (95% CI: 6.81, 9.96) for the ERR risk model. The parameter for attained age decreased from 5.71 to 5.24 (95% CI: 4.24, 6.36) for the EAR risk model.

Based on the ERR model, we estimated that 19.8% of solid cancers among the medical X-ray workers were radiation-related. The attributable fraction varied from 42.0% for workers first employed before 1955 to 1.1% for those first employed in 1975–1980.

DISCUSSION

The present analysis is a reanalysis of cancer incidence data from the Chinese medical X-ray workers study that were reported previously [9–12]. We now have incorporated dose information and estimated dose-response relationships for solid cancer incidence. The medical X-ray workers were predominantly exposed to X-rays with photon energies of 25–40 keV, which is similar to exposures for U.S. radiation technologists [23]. The mean reconstructed badge dose was 0.25 Gy, and the mean cumulative colon dose, an approximate proxy for dose to solid organs overall, was 0.086 Gy (median, 0.042 Gy). These are within the dose range of particular interest for the setting of radiation protection standards. The ICRP recommends an average annual effective dose limit for occupational exposures of 20 mSv/year, which translates to a cumulative dose of 0.5 Sv over a 25 year work history [24–26]. We observed statistically significant radiation dose-response relationships for all solid cancers combined for both relative and absolute risk. Based on linear dose-response risk models derived from solid cancer incidence data and using colon dose, the sex-averaged ERR/Gy at age 50 years was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.48, 1.45) for the CMXW, and the EAR was 22 per 104PY-Gy.

Relevant comparisons for these estimates from the literature include those for workers in the nuclear industry [4–6] and other radiation workers [7], persons exposed from environmental radiation releases near the Techa River in the former Soviet Union [8] and survivors of the atomic bomb explosions in Japan [2] (Tables 3, 4). Some of the nuclear/radiation worker studies overlap, as the pooled analysis of Richardson et al. (2015) [6] is inclusive of others, but all are shown because some reports pertain to cancer incidence and others to cancer mortality. Although the present study was of incidence, we include comparisons with mortality risk estimates for the ERR/Gy as well, because it is not clear that the case fatality rate is related to radiation dose; that is, the slope of the dose-response might be similar for incidence and mortality. Some of the risk estimates in Table 3 are based on external (badge) dose, while others are based on internal organ dose with allowance for attenuation within the body.

With consideration of the dose metric used and attained age, our ERR/Gy estimates are within the ranges that have been reported for occupationally or environmentally exposed Caucasian populations (Table 3). The estimate for the CMXW based on badge dose is 0.30 (95% CI: 0.17, 0.51). Results from the 3rd NRRW analysis [7] for solid cancer incidence in terms of badge dose are similar to those from the CMXW study, with broad overlap in confidence intervals. NRRW results in terms of cancer incidence are very similar to those for cancer mortality. For the BNFL cohort, the ERR/Gy was higher for workers only exposed to external radiation (0.87/Gy; 90% CI: 0.36, 1.44) than when workers with potential exposure to internal radiation also were included (ERR/Gy=0.29; 90% CI: 0.02, 0.59). Results from the pooled INWORKS study of nuclear workers showed an ERR/Gy of 0.48 (90% CI: 0.20, 0.79) based on colon dose [6], somewhat lower than the estimate from the present study (0.87/Gy). Our ERR estimate is statistically compatible with findings from the Techa River study in terms of stomach dose (smoking-adjusted ERR/Gy=0.8; 95% CI: 0.1, 1.5[8] (Table 3); thus, results from these studies are broadly consistent concerning effects of long-term, fractionated exposure to low doses of radiation from occupational or environmental sources for Caucasian and Asian populations.

The sex-specific ERR estimates for the CMXW study are higher than those for the LSS as published in BEIR VII [20], and effects of attained age and age at first exposure on the ERR also are different. Regarding the first difference between CMXW and LSS, the studies had different types of radiation exposure. The CMXW study population was chronically exposed to fractionated low-dose, low linear energy transfer ionizing radiation, whereas the LSS population was acutely exposed to ionizing radiation including both gamma and neutron components. This difference may not be enough to explain the higher ERR for the CMXW study relative to the LSS. If we employ a dose and dose-rate effectiveness factor of 1.5 [20] with estimates from the LSS, the difference remains and, indeed, is even larger. Demographic characteristics of CMXW and LSS populations also are different. CMXW cohort members all were of working age and 80% male, whereas the LSS cohort includes all ages and is 41% male [2]. CMXW members were exposed to fractionated radiation throughout their working lives, whereas LSS members were acutely exposed to radiation at their ages at the time of bombing. Age at exposure has a different interpretation in the two situations, and that may explain why age at exposure had a lesser effect on the ERR model for the CMXW. For effect modification due to attained age, reasons for the opposite results for the ERR between CMXW and LSS are unclear. The Techa River study and INWORKS study did not find effects of attained age on the ERR.

Based on linear dose-response EAR risk models, the gender-averaged EAR/104 PY-Gy at age 50 for the CMXW study was 22 (95% CI: 14, 32). The EAR coefficient was greater for males than for females; an opposite pattern was seen for the LSS (Table 4); however, the EAR/104 PY-Gy for both males and females in the CMXW study are statistically compatible with those for the LSS. The modifying effect of attained age on the EAR is in the positive direction for both the CMXW study and the LSS.

Strengths of this study include its large size, the inclusion of an internal comparison group of physicians from the same hospitals as the X-ray workers, the relative homogeneity of types of radiation exposure (X-ray photons only), estimates of radiation dose, the absence of likely confounding occupational exposures, long-term follow-up, and the use of cancer incidence rather than mortality.

The study also has important limitations. These include radiation dosimetry based on a composite of individual and group level data, the use of colon dose as a proxy for dose to all solid organs, and possible differences between X-ray workers and the comparison cohort with respect to non-radiation cancer risk factors. In addition, although follow-up was relatively long (mean, 25.7 y), it was still insufficient to provide an evaluation of lifetime radiation-related cancer risks.

There are several sources of uncertainties in dose estimates. Mathematical models for dose reconstruction were based on work histories for a selected 14% sample of workers and extrapolated to the cohort as a whole. The only model input data available for the entire cohort was year started work and year stopped work. Colon dose was chosen as the primary metric for solid cancer risk models, which is in accord with prior LSS [2, 20] analyses; however, the medical X-ray workers were exposed to far lower energy, and less penetrating, photon radiation than were the atomic bomb survivors (25–40 keV X-rays versus 0.5–2 MeV gamma-rays), so colon dose is a less representative dose for other organs, particularly more superficial organs. We assumed constant energy of X-rays over calendar time, which probably is inaccurate. Conversion parameters from ICRP [16] that were employed in this study may not be applicable to Asian populations [27]. Despite these uncertainties, reconstructed physical doses and biologically-based doses were strongly correlated for this study [18].

Even though the persons in the comparison group came from the same hospitals as the X-ray workers, thereby controlling for regional effects, they may have differed with respect to the distribution of other cancer risk factors. The exposed cohort included a combination of physicians and technologists, whereas the comparison cohort included only physicians, raising the possibility of socioeconomic differences between the groups. A questionnaire administered to 2304 X-ray workers and members of the comparison group indicated similarities with respect to most known cancer risk factors, but there were notable differences for those first employed after 1970 or before age 40 years with respect to education, smoking, tea drinking (possibly protective against some cancers) and history of liver disease [28]. Observed excesses of lung, esophageal, and liver cancers among X-ray workers may be related, in part, to differences in smoking and hepatitis infection [12]; however, we found that risks of all solid cancer with and without lung and liver cancer included were very similar. Similar findings were reported for the NRRW and INWORKS studies; the ERR/Gy estimate for solid cancers was little changed when cancers of the lung were excluded [6, 7].

Follow-up for cancer incidence is not based on population-based cancer registries and its completeness is uncertain. In addition, thirty percent of cancers were not histologically confirmed; however, this is not an important limitation for the present analysis. Most other cancers were diagnosed radiologically. Although this could lead to confusing metastatic and primary cancers and resultant misclassification of type of primary cancer, it should not greatly compromise analyses at the level of all solid cancers combined.

In summary, based on doses received before January 1st, 1996 and cancer cases that occurred during 1950–1995 among 27,011 Chinese medical X-ray workers and 25,782 comparison cohort members from the same hospitals, we observed a statistically significant dose-response relationship for solid cancer incidence. Risk estimates are consistent with those from other studies of solid cancer risk in relation to prolonged exposure to low dose-rate radiation from occupational and environmental sources in Caucasian populations. The present study contributes new knowledge about solid cancer risk in relation to radiation dose among persons chronically exposed to fractionated low dose-rate radiation in an Asian population. Longer follow-up is needed to estimate lifetime risks, refine the current risk models and conduct cancer site-specific risk analysis for the Chinese medical X-ray workers.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND IMPACT.

In a long-term study of 27,011 Chinese medical X-ray workers chronically exposed to fractionated low dose and low dose-rate ionizing radiation and a comparison group of 25,782 physicians who did not use X-ray equipment in their work, the incidence of solid cancers previously was found to be elevated among the X-ray workers, but initial reports lacked information on radiation dose. The present study incorporates new information about radiation doses and provides quantitative estimates of solid cancer risk in relation to radiation dose for an Asian population with chronic low dose-rate exposure.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502760); the Institute of Radiation Medicine, Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) & Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (SF1210); PUMC Youth Fund and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (33320140032); the Science Research Foundation for Doctor-Subject of High School of the National Education Department of China (20121106120041); and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services, USA. This work was supported by the China Scholarship Council to allow the first author to communicate with co-investigators in the Radiation Epidemiology Branch, National Cancer Institute.

This work is a reanalysis of data collected by the National Coordinating Research Group of Dose-Effect Relationship in Medical X-ray workers in China. We thank Dr. Charles Land for his thoughtful advice concerning the data analysis. We also give thanks to Dr. Dale L. Preston from Hirosoft International, who provided very important help concerning risk analysis using Epicure. We would like to thank Dr. Martha S. Linet, chief of the Radiation Epidemiology Branch, DCEG, at the National Cancer Institute in the USA, for encouraging progress of this study. This report makes use of data obtained from the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. RERF is a private, non-profit foundation funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the latter through the National Academy of Sciences. The data include information obtained from the Hiroshima City, Hiroshima Prefecture, Nagasaki City, and Nagasaki Prefecture Tumor Registries and the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Tissue Registries. The conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the scientific judgment of RERF or its funding agencies.

Abbreviations used

- AP

antero-posterior

- BNFL

British Nuclear Fuels plc

- CI

confidence interval

- CMXW

Chinese medical x-ray workers

- EAR

excess absolute risk

- ERR

excess relative risk

- ICRP

International Commission on Radiological Protection

- INWORKS

International Nuclear Workers Study

- LSS

Life Span Study

- NRRW

UK National Registry for Radiation Workers

- PY

person-years

- y

years

References

- 1.UNSCEAR (United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation) Sources, effects and risks of ionizing radiation. UNSCEAR 2012 Report Scientific Annex A: Attributing health effects to ionizing radiation exposure and inferring risks. 2015 http://www.unscear.org/en/publications/2012.html.

- 2.Preston DL, Ron E, Tokuoka S, Funamoto S, Nishi N, Soda M, Mabuchi K, Kodama K. Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors: 1958–1998. Radiat Res. 2007;168(1):1–64. doi: 10.1667/RR0763.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boice JD., Jr . Ionizing radiation. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr, editors. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2006. pp. 259–293. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillies M, Haylock R. The cancer mortality and incidence experience of workers at British Nuclear Fuels plc, 1946–2005. J Radiol Prot. 2014;34(3):595–623. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/34/3/595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schubauer-Berigan MK, Daniels RD, Bertke SJ, Tseng C-Y, Richardson DB. Cancer mortality through 2005 among a pooled cohort of U.S nuclear workers exposed to external ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 2015;183:620–631. doi: 10.1667/RR13988.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson DB, Cardis E, Daniels RD, Gillies M, O’Hagan JA, Hamra GB, Haylock R, Laurier D, Leurad K, Moissonnier M, Schubauer-Berigan MK, Thierry-Chef I, Kesminiene A. Risk of cancer from occupational exposure to ionizing radiation: retrospective cohort study of workers in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States (INWORKS) BMJ. 2015:351h5359. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muirhead CR, O’Hagan JA, Haylock RGE, Phillipson MA, Willcock T, Berridge GL, Zhang W. Mortality and cancer incidence following occupational radiation exposure: third analysis of the National Registry for Radiation Workers. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:206–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis FG, et al. Solid Cancer Incidence in the Techa River Incidence Cohort: 1956–2007. Radiat Res. 2015;184(1):56–65. doi: 10.1667/RR14023.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang JX, Boice JD, Jr, Li B, Zhang JY, Fraumeni JF., Jr Cancer among medical diagnostic X-ray workers in China. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:344–50. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.5.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang JX, Inskip PD, Boice JD, Li BX, Zhang JY, Fraumeni JF., Jr Cancer incidence among medical diagnostic X-ray workers in China, 1950 to 1985. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:889–95. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JX, Li BX, Gao ZW, Xu J, Zhang JY, Aoyama T, Sugahara T. Epidemiological findings and requirement for dose reconstruction among medical diagnostic x ray workers in China. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1998;77:119–122. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JX, Zhang LA, Li BX, Zhao YC, Wang ZQ, Zhang JY, Aoyama T. Cancer incidence and risk estimation among medical X-ray workers in China, 1950–1995. Health Phys. 2002;82:455–66. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang LA, Jia D, Chang H, Zhang W, Dai G, Ku M, Zhao Y, Chen Z, Aoyama T, Norimura T, Sugahara T. The main characteristics of occupational exposure for Chinese medical diagnostic X ray workers. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1998;77:83–86. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang LA, Jia D, Chang H, Zhang W, Dai G, Ku M, Zhao Y, Zhang C, Aoyama T, Norimura T, Sugahara T. A retrospective dosimetry method for occupational dose for Chinese medical diagnostic X ray workers. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1998;77:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang LA, Yang LH. Method for Chinese radio technologists dose reconstruction. Chinese J Radiol Med Prot. 1984;4:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICRP (International Commission on Radiological Protection) International Commission on Radiological Protection Publication 74, Annals of the ICRP. 3. Vol. 26. Oxford: Elsevier; 1997. Conversion coefficients for use in radiological protection against external radiation; p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu WZ, Yu A, Zhang WY, Dai GF, Zhang LA. Dose estimation by EPR spectroscopy of tooth enamel in Chinese medical diagnostic X-ray workers. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2006;118:102–105. doi: 10.1093/rpd/nci336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang ZQ, Liu XP, Li J, Wang Q, Tang WS, Sun YM, Wang XL, Aoyama T, Sugahara T. Retrospective dose reconstruction for medical diagnostic X ray workers in China using stable chromosome aberrations. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1998;77:87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straume T, Lucas JN, Tucker JD, Bigbee WL, Langlois RG. Biodosimetry for a worker using multiple assays. Health Phys. 1992;62(2):122–130. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199202000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NRC (National Research Council) Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation BEIR VII Phase 2. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2006. p. 406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preston DL, Lubin JH, Pierce DA, McConney ME. Epicure user’s guide. Seattle, WA: Hirosoft International Corporation; 1993. p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- 22.RERF (Radiation Effects Research Foundation) Life Span Study Cancer Incidence Data, 1958–1998. [accessed July 18, 2015];Radiation Effects Research Foundation Web site. 2007 http://www.rerf.jp/library/dl_e/index.html.

- 23.Simon SL, Weinstock RM, Doody MM, Neton J, Wenzl T, Stewart P, Mohan AK, Yoder RC, Hauptmann M, Freedman DM, Cardarelli J, Feng HA, et al. Estimating historical radiation doses to a cohort of U.S. radiologic technologists. Radiat Res. 2006;166:174–92. doi: 10.1667/RR3433.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ICRP (International Commission on Radiological Protection) General principles for the radiation protection of workers. ICRP Publication 75. Ann ICRP. 1997;27(1) doi: 10.1016/s0146-6453(97)88275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ICRP (International Commission on Radiological Protection) The 2007 recommendations of the international commission on radiological protection. Oxford: Elsevier; 2007. p. 332. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrixon AD. New ICRP recommendations. J Radiol Prot. 2008;28:161–168. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/28/2/R02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C, Lee C, Lee JK. Applicability of dose conversion coefficients of ICRP 74 to Asian adult males: Monte Carlo simulation study. Appl Radiat Isot. 2007;65:593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao ZW, Wang JX, Li BX, Xu J. Comparative investigation on cancer-related factors in Chinese medical X-ray workers. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 1998;77:133–135. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.