Abstract

Background and aims

There is a documented link between common psychiatric disorders and substance use in adolescent males. This study addressed two key questions: 1) Is there a within-person association between an increase in psychiatric problems and an increase in substance use among adolescent males?; and 2) Are there sensitive periods during male adolescence when such associations are more evident?

Design

Analysis of longitudinal data collected annually on boys randomly selected from schools based on a comprehensive public school enrollment list from the Pittsburgh Board of Education

Setting

Recruitment occurred in public schools in Pittsburgh, Pennysylvania, USA.

Participants

503 boys assessed at ages 13-19, average cooperation rate = 92.1%

Measurements

DSM-oriented affective, anxiety, and conduct disorder problems were measured with items from the caregiver, teacher, and youth version of the Achenbach scales. Scales were converted to T-scores using age- and gender-based national norms and combined by taking the average across informants. Alcohol and marijuana use were assessed semi-annually by a 16-item Substance Use Scale adapted from the National Youth Survey.

Findings

When male adolescents experienced a one-unit increase in their conduct problems T-score, their rate of marijuana use subsequently increased by 1.03 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01, 1.05), and alcohol quantity increased by 1.01 (95% CI: 1.0002, 1.02). When adolescents experienced a one-unit increase in their average quantity of alcohol use, their anxiety problems T-score subsequently increased by 0.12 (95% CI: 0.05, 0.19). These associations were strongest in early and late adolescence.

Conclusions

When adolescent boys experience an increase in conduct disorder problems, they are more likely to exhibit a subsequent escalation in substance use. As adolescent boys increase their intensity of alcohol use, they become more likely to develop subsequent anxiety problems. Developmental turning points such as early and late adolescence appear to be particularly sensitive periods for boys to develop comorbid patterns of psychiatric problems and substance use.

Keywords: comorbidity, substance use, depression, anxiety, conduct disorder

Introduction

Common psychiatric problems, including conduct disorder, depression and anxiety, are important risk factors for alcohol and marijuana use in adolescence 1-8. The consistent link between common psychiatric problems and substance use has led researchers and practitioners to suggest that by intervening early in adolescence to treat psychiatric disorders, we could reduce substance use problems by late adolescence 2,4. However, two key questions need to be answered before we can conclude that intervening on psychiatric problems will be an effective strategy to reduce substance use in adolescence.

First, do adolescents who exhibit an increase in their psychiatric problems exhibit a subsequent increase in their substance use? Longitudinal studies provide consistent evidence that youth with higher levels of psychiatric problems are more likely to engage in substance use during adolescence 3. Etiologic theories to explain this comorbidity are based on causal pathway models, in which conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety result in substance use 1,4,6,7. Frequent explanations for these relationships are that children and adolescents with conduct disorder gravitate towards social environments that facilitate problem behaviors such as substance use 5,8 and that drugs like alcohol and marijuana are used to self-medicate or alleviate persistent symptoms of sadness and anxiety 9,10. However, existing studies have primarily examined whether youth with higher levels of psychiatric problems are more likely to use and abuse substances (i.e., inter-individual differences), rather than examining whether adolescents tend to increase their level of substance use during periods when their psychiatric problems increase (i.e., intra-individual change). The latter approach represents a more direct examination of the self-medication hypothesis, where adolescents increase their substance use in an attempt to manage emerging psychiatric problems. Few longitudinal studies have examined the association between intra-individual changes in mental health problems and substance use. By examining within-individual change, causal inference is enhanced because selection effects and all factors that vary between individuals (e.g., genotype, early trauma, prenatal complications) are ruled-out as potential confounds. It also provides a better indication of whether treating an adolescent’s psychiatric problems could potentially lead to a reduction in his substance use.

The second key question is: Are there sensitive periods during adolescence when psychiatric problems play a particularly strong role in shaping substance use? Cerdá and colleagues 9 found no evidence that there was a sensitive period in which acute and chronic psychiatric problems were more strongly related to the onset of alcohol and marijuana use from childhood to late adolescence. Specifically, both recent (past year) and cumulative conduct disorder problems were associated with earlier alcohol and marijuana use onset in a cohort of boys followed from ages 7-19, whereas cumulative, but not recent, depression problems were associated with earlier alcohol use onset. However, there was no particular age of substance use initiation when psychiatric problems mattered the most. In contrast, Maslowsky and colleagues 10 and Gibbons and colleagues 11 found evidence indicating that early conduct problems were a stronger predictor of alcohol and marijuana use in late adolescence than conduct problems in middle adolescence. However, these three studies focused on between-individual differences in psychiatric problems and substance use. Therefore, it is unclear whether there is a specific developmental period during adolescence when youth are more likely to escalate their drug and alcohol use in response to emerging psychiatric problems.

One way to effectively address these two key questions is to use longitudinal data to examine whether youth tend to increase the frequency of their substance use after they experience an increase in their psychiatric problems, and test whether this association changes across development. This type of within-person change analysis eliminates the possibility that time-stable individual differences such as genotype, race/ethnicity, personality traits, family history of psychiatric problems and substance dependence, and parenting problems 12 can explain the association between changes in psychiatric problems and substance use across adolescence 13. Hence, it controls for all unmeasured time-invariant confounders. In addition, measured time-varying confounders can also be included as control variables (e.g., increase affiliation with deviant peers). Using this approach, researchers have shown that change in alcohol abuse or dependence and nicotine dependence in early adulthood predicted change in major depression in a birth cohort in New Zealand 14,15. Additionally, increasing frequency of cannabis use was associated with concurrent increasing depression problems in four Australasian birth cohorts 16. But to our knowledge, no research has used this approach to establish the directionality of the relationship between common psychiatric problems and substance use: that is, to evaluate whether (1) an increase in conduct disorder, depression and anxiety problems leads to a subsequent increase in alcohol and marijuana use; (2) an increase in alcohol and marijuana use leads to a subsequent increase in conduct disorder, depression and anxiety; or (3) a reciprocal relationship exists between psychiatric problems and substance use.

Thus, the aims of the present study are to address the following questions: do adolescents experience an increase in the frequency and quantity of their alcohol and marijuana use following an increase in conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety problems? Are there specific periods during adolescence when increases in these mental health problems are more strongly related to escalations in substance use than others? We examine these questions in a longitudinal urban sample of males followed from ages 13 to 19, with yearly measures of psychiatric problems and substance use quantity and frequency. To establish the directionality of these associations, we examine both whether increases in alcohol and marijuana follow increases in conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety, and whether increases in conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety follow increases in alcohol and marijuana use.

Methods

Sample

Data are from the youngest cohort of the Pittsburgh Youth Study (PYS) 17-20. This sample has been described in depth elsewhere.9,17-20 Briefly, participants included first-grade boys enrolled in 31 public schools in Pittsburgh (PA) in 1987-1988. A random sample of boys was invited for an initial multi-informant screening. The screen involved assessing the boys’ conduct problems (e.g., fighting, stealing) using ratings collected from the parents, teachers, and the boys themselves. Boys whose composite conduct problem scores fell within the upper 30th percentile, together with an approximately equal number of participants randomly selected from the remaining end of the distribution, were selected for longitudinal follow-up (total N=503). The sample is predominantly Black (56%) and White (41%) with 3% Asian, Hispanic, and mixed-race.

Participants were assessed annually or semi-annually, depending on the measure, for thirteen years. Caretakers provided informed consent and adolescents provided assent until age 17 and consent thereafter. We restricted analysis to adolescents at ages 13-19, as substance use by year was rare at younger ages: 93.9% and 84.5% did not use marijuana or alcohol, respectively, on any occasion between the ages of 7-12. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

Substance use measures

Alcohol and marijuana use were assessed semi-annually by a 16-item Substance Use Scale 21,22 adapted from the National Youth Survey. Adolescents were queried about timing, quantity, and frequency of alcohol (beer, wine, and liquor) and marijuana use. We defined “marijuana frequency” as the number of occasions of marijuana use in the past year. We defined “alcohol frequency” as the number of occasions of drinking in the past year. We defined “alcohol quantity” as the average number of drinks per occasion in the past year. For phases separated by only 6 months, past-year values were constructed by taking the average of the two semi-annual interviews.

Psychiatric problem domain measures

Affective, anxiety, and conduct problems were measured with items from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBLC), Teacher Report Form (TRF), Youth Self-Report (YSR), and Young Adult Self-Report (YASR) from the Achenbach system of assessment. 23-26 DSM-oriented problem domains were measured with items rated as very consistent with DSM-IV symptoms of affective disorders, anxiety disorders, and conduct disorder by a group of mental health professionals. 23-25 The scales were administered to caregivers (CBCL) and teachers (TRF) from age 7 to 16, and youth from age 10 to 19 (YSR until age 17, and the YASR thereafter). 23-25. Items were scored as 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true (number and type of scale items for the CBCL, TRF and YSR are listed in Appendix A).26,27 In order to facilitate comparison across informants, total scores for each scale were converted to t-scores based on age- and gender-specific national norms .26 An average T-score was then calculated for years when multiple informants completed the scales.

The average internal consistency coefficients for the caregiver, teacher, and youth depression scales were 0.82, 0.76, and 0.81, respectively. For the anxiety scales, the internal consistency coefficients for caregiver, teacher and youth scales were 0.72, 0.73, and 0.67, respectively. For the conduct disorder scale, the internal consistency coefficients were 0.91, 0.9, and 0.83 for caregiver, teacher, and youth scales, respectively.26 These scales have been shown to discriminate between clinic-referred adolescents with depressive, anxiety, and conduct disorders and non-referred adolescents 28,29. All the scales used have previously shown acceptable concurrent and predictive validity in ROC analyses comparing the scales with official records of offense and delinquency or by assessing discrimination between adolescents referred to psychiatric clinics and non-referred adolescents.30,31

Time-varying covariates

Several potential time-varying confounding factors were included in the current study to parse out the effect of psychiatric problems from the constellation of time-varying risk factors that could increase both psychiatric problems and substance use. The selection of confounders was based on theory and a review of the literature, as detailed below. “Family factors” included changes in socioeconomic status (SES), assessed yearly by applying the Hollingshead Index of Social Status to data provided by the primary caretaker or youth no longer living with family beginning at age 1632; changes in parental supervision/involvement, a 43-question scale concerning caretakers’ knowledge of the youths’ whereabouts, the frequency of joint discussions, planning, and activities, and the amount of time that the youth is unsupervised 33-35; positive parenting, a scale measuring perception of frequency of positive responses to youth behavior 18; parental stress, a 14-item scale measuring perceived stress levels and caretakers’ abilities to cope with stress in the previous month 18; and parental use of physical punishment, drawn from a scale that measures parental discipline strategies 17. “Peer Variables” consisted of changes in youth peer delinquency and peer substance use, a 15-item scale that corresponds to a self-reported delinquency scale. 21

Analyses

Analyses were conducted in R version 3.0.2 and 3.0.3. Missing data in the covariates were imputed using R package ‘mice’ 36 for “multivariate imputation by chained equations,” an implementation of fully conditional specified models for imputation. The fully conditional approach differs from the more traditional joint modeling approach by specifying a multivariate imputation model on a variable-by-variable basis 36. This fully conditional approach is used as an alternative to traditional joint modeling when no suitable multivariate distribution can be found 36. We imputed 20 datasets, and in subsequent analyses used the R package ‘mitools 37 to pool the results of functions run on the 20 data sets using Rubin’s Rules38.

We employed quasi-Poisson regression techniques to assess the fixed effects that one-year-lagged changes in psychiatric problems had on subsequent changes in alcohol use frequency/quantity and marijuana use frequency from ages 13 to 19. Quasi-Poisson models are an approach to dealing with over-dispersion, which was apparent in initial Poisson models. They use the mean regression function and the variance function from Poisson generalized linear models but leave the dispersion parameter unrestricted (not assumed to be fixed at 1) and estimate it from the data. Unlike negative binomial models, the variance is assumed to be a linear function of the mean.39 This strategy leads to the same coefficient estimates as a standard Poisson model but standard errors are adjusted for over-dispersion 40. Following the “dummy variable method” for fixed effects in Poisson models 41 we included k - 1 dummy variables to represent the sample participants in each model.

A series of models were fit sequentially to test the association of each one-year-lagged psychiatric problem domain with each substance use outcome. First, we regressed separately each one-year-lagged shift in the average psychiatric problem T-scores (interpreted as a within-individual one-unit change in the T-score) on each substance use outcome. Within these models, age-related changes in substance use were controlled for using natural cubic splines. Natural cubic splines are a flexible smoothing approach for non-linear relationships, and are composed of piecewise polynomial functions that split the continuous age variable into separate line segments, each free to have its own shape 42,43. Segments are joined by “knots,” which we specified a priori to result in line segments for ages 13-14, 15-16, and 17-19. Slopes are constrained to converge at each knot 42,43.

Second, we sequentially tested groups of potential confounders. All covariates (except age) were back-lagged two years, so that they would be modeled prior to the measurement of the exposure. This ensured that the estimated total effect of change in psychiatric problems on change in substance use included effects mediated through the covariates that occurred contemporaneous to changes in psychiatric problems. In our second set of models, we adjusted for age, SES, substance use variables that were not modeled as the outcome (e.g., if marijuana use was the outcome, we adjusted for alcohol frequency and quantity), and measures of psychiatric problems that were not the exposure of interest (e.g., if conduct problems were the exposure of the interest, we adjusted for affective and anxiety problems). In our third and fourth sets of models, we adjusted for age and parenting variables and age and peer variables, respectively. In our fifth set of models, we adjusted for covariates that were significant in models 2-4.

Third, we tested whether age modified the effect of our exposures by including a product term between exposure and each age spline. Significant effect measure modification was then probed to clarify how the association between psychiatric problems and substance use changed across the age splines.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to establish the directionality of the association between psychiatric problems and substance use. We thus estimated, with linear fixed effects models, the effect that changes in one-year-lagged substance use had on change in psychiatric problem domains in the following year. We followed the same modeling strategy for these models as we did with our primary models. We adjusted for groups of confounders as described above, first adjusting for SES, psychiatric problem domains that were not modeled as the outcome (e.g., if conduct problems was the outcome, we adjusted for affective and anxiety problems), and measures of substance use that were not the exposure of interest (e.g., if marijuana use was the outcome, we adjusted for alcohol frequency and quantity). Next we adjusted for parenting variables and peer variables, respectively. Finally, we adjusted for covariates that were significant in any of the previous groups of confounder models. Covariates were lagged one year prior to the exposure measure (i.e., T-2), to avoid blocking the causal pathway between substance use and psychiatric problems.

Results

Table 1 shows mean substance use and psychiatric problem counts over time, as well as demographic characteristics at baseline. The reports of particular informants in our psychiatric problem measures did not influence the associations between psychiatric problems and substance use (see Appendix B). Table 2 displays the exponentiated coefficients and confidence intervals of quasi-Poisson models, which can be interpreted as rate ratios. Table 2 shows the rate of substance use associated with a one-unit within-subject change in lagged psychiatric problems. Changes in lagged conduct problems were positively associated with changes in marijuana frequency. During years in which adolescents experienced a one-unit increase in conduct problems, the rate at which they smoked marijuana the following year increased 1.03 times (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01, 1.05). For a standard deviation change in conduct problems, this is equivalent to a 1.15 times higher rate of marijuana use frequency (95% CI: 1.05. 1.25). The magnitude of this association did not change appreciably after adjusting for potential confounders, including alcohol quantity and frequency, SES, affective and anxiety problems, parenting, and peer deviance. Changes in lagged conduct problems were also associated with changes in alcohol quantity, only after adjusting for peer deviance. During years in which adolescents experienced a one-unit increase in conduct problems, the rate of their average alcohol consumption per occasion the following year increased by 1.01 (95% CI: 1.0002, 1.02). For a standard deviation change in conduct problems, this is equivalent to a 1.05 times higher rate of alcohol use (95% CI: 1.001, 1.1). Associations of all covariates with substance use are presented in Appendix C, Table C1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of un-imputeda. original data

| Mean (SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Age 13 (N=482) |

Age 14 (N=479) |

Age 15 (N=476) |

Age 16 (N=472) |

Age 17 (N=466) |

Age 18 (N=460) |

Age 19 (N=451) |

| Marijuana frequency |

6.63 (38.82) | 18.67 (64.79) | 29.23 (81.42) | 42.5 (114.8) | 39.43 (94.79) | 64.46 (143.04) | 50.8 (111.45) |

| Alcohol frequency |

5.66 (30.60) | 14.78 (63.36) | 13.28 (44.25) | 18.6 (54.51) | 27.28 (73.76) | 45.36 (110.82) | 49.38 (101.36) |

| Alcohol quantity | 1.19 (2.43) | 1.85 (3.09) | 2.2 (3.38) | 2.68 (3.56) | 3.04 (3.8) | 4.04 (4.25) | 4.25 (4.03) |

| Affective problems t-score |

53.84 (3.55) | 53.66 (3.74) | 53.15 (3.72) | 52.94 (4.18) | 52.52 (4.76) | 152.6 (4.4) | 52.28 (4.03) |

| Anxiety problems t-score |

53.55 (3.62) | 53.25 (3.62) | 52.73 (3.59) | 52.35 (3.68) | 51.99 (4.32) | 52.14 (4.52) | 51.52 (3.87) |

| Conduct problems t-score |

57.27 (6.67) | 56.96 (6.48) | 56.1 (5.68) | 55.1 (5.85) | 53.65 (6.09) | 52.86 (5.41) | 52.23 (5.3) |

| N (%) | |||||||

| SES | |||||||

| 1st quartile | 44 (8.7) | 48 (9.5) | 45 (8.9) | 84 (16.7) | 215 (42.7) | 193 (38.4) | 114 (22.7) |

| 2nd quartile | 117 (23.3) | 101 (20.1) | 98 (19.5) | 100 (19.9) | 107 (21.3) | 125 (24.9) | 117 (23.3) |

| 3rd quartile | 161 (32) | 154 (30.6) | 147 (29.2) | 101 (20.1) | 57 (11.3) | 71 (14.1) | 58 (11.5) |

| 4th quartile | 140 (27.8) | 148 (29.4) | 154 (30.6) | 149 (29.6) | 48 (9.5) | 33 (6.6) | 29 (5.8) |

| Missing | 41 (8.2) | 52 (10.3) | 59 (11.7) | 69 (13.7) | 76 (15.1) | 81 (16.1) | 185 (36.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Black | 280 (55.7) | ||||||

| White/Other | 223 (44.3) |

The number of participants at each age group decreases over time because not all subjects had complete data. See the methods section for a discussion of the multiple imputation techniques we implemented to deal with missing data.

Table 2.

Changes in substance use frequency and quantity associated with lagged changes in psychiatric problem T-scores (N=487)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | ||||||

| Marijuana frequency | |||||||||||||||

| Affective problems | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 1.005 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.03 |

| Anxiety problems | 1.003 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.001 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.002 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.002 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 |

| Conduct problems | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 |

| Alcohol frequency | |||||||||||||||

| Affective problems | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 |

| Anxiety problems | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.02 |

| Conduct problems | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 |

| Alcohol quantity | |||||||||||||||

| Affective problems | 1.002 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.000 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.002 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.003 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 |

| Anxiety problems | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| Conduct problems | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.9995 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.9995 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.0003 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.0002 | 1.02 |

Note. Separate models were run for affective, anxiety, and conduct problems. Model 1 for each exposure-outcome combination controls only for age trends using splines. Model 2 controls for age, prior SES, measures of prior substance use variables that were not modeled as the outcome, and measures of prior psychiatric problems that were not the exposure of interest. Model 3 controls for age and measures of prior parenting. Model 4 controls for age and measures of prior peer delinquency and drug use. Model 5 controls for age and covariates that were significant in the previous groups of confounder models. For marijuana frequency: The affective problems model controls for age, prior alcohol frequency, alcohol quantity, and peer delinquency. The anxiety problems model controls for age, prior alcohol frequency, alcohol quantity, peer delinquency, and peer drug use. The conduct problems model controls for age, prior alcohol frequency and alcohol quantity. For alcohol frequency models, the affective, anxiety, and conduct problems models control for age, prior marijuana frequency and alcohol quantity. For alcohol quantity: The affective problems model controls for age, prior marijuana frequency, alcohol frequency, conduct problems, and peer drug use. The anxiety problems model controls for age, prior marijuana frequency, alcohol frequency, conduct problems, and peer delinquency. The conduct problems model controls for age, prior marijuana frequency, alcohol frequency, and peer drug use. Estimates of all variables are included in Appendix C in the online supplement.

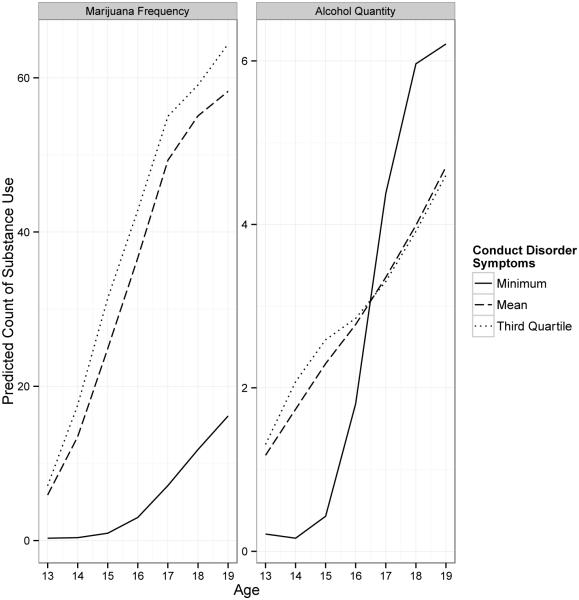

Table 3 presents results for tests of effect measure modification of the association between conduct problems and marijuana frequency and alcohol quantity by age. Because splines are polynomial functions, there is no simple quantitative interpretation of individual effect modification terms; however, the significance of the coefficients implies that the associations between lagged conduct problems and marijuana frequency, and lagged conduct problems and alcohol quantity, differed by age. For ease of interpretation we present these results in Figure 1, which shows the predicted values of substance use outcomes associated with minimum, mean, and third-quartile levels of lagged conduct disorder T-scores, over time. Compared to minimal changes in lagged conduct problems, adolescents with mean or third-quartile levels of change in lagged conduct problems show markedly different marijuana frequency trajectories, which become the most disparate at ages 17-19. Compared to minimal changes in lagged conduct problems, adolescents with mean or third-quartile levels of change in lagged conduct problems show higher alcohol quantity in early adolescence but lower alcohol quantity in later adolescence.

Table 3.

Age-related differences in the association between changes in lagged conduct disorder T-scores and changes in marijuana frequency and alcohol quantity (N=487)

| Marijuana Frequency | Alcohol Quantity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | |||

|

|

||||||

| Conduct problems | 1.05 | 0.99 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 |

| Age 13-14 | 59.23 | 2.48 | 1414.86 | 35.33 | 5.85 | 213.43 |

| Age 15-16 | 43.47 | 0.03 | 54422.05 | 18.59 | 1.05 | 329.56 |

| Age 17-19 | 49.12 | 7.97 | 302.86 | 41.54 | 12.59 | 137.02 |

| Conduct problems*Age 13-14 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| Conduct problems *Age 15-16 | 0.99 | 0.88 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.03 |

| Conduct problems * Age 17-19 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

Figure 1.

Predicted counts of substance use by age, given three levels of change in conduct problems. (N = 483).

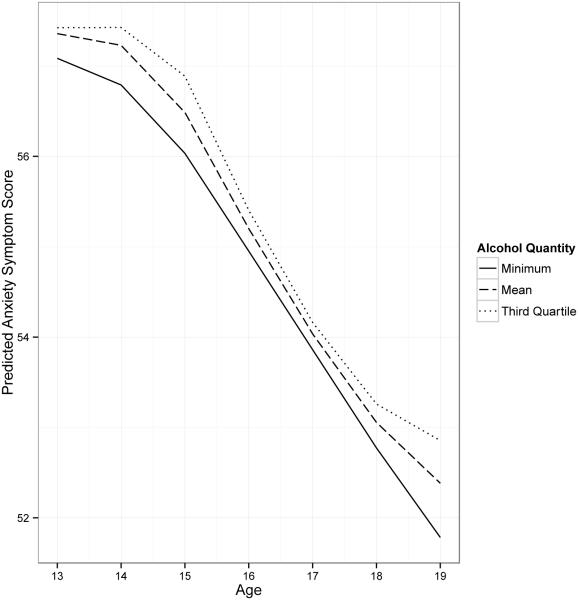

The results of our sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 4 and 5, and Figure 2. Table 4 displays the change in psychiatric problems associated with a one-unit change in lagged substance use in the prior year. There was one reverse association: while changes in lagged anxiety problems were not associated with changes in substance use, the opposite did occur: changes in lagged alcohol quantity in the past year were positively associated with changes in anxiety problems. During years in which adolescents experienced a one-unit increase in the average quantity of alcohol consumed when drinking, their anxiety problems T-score increased the following year by 0.12 (95% CI: 0.05, 0.19). For a standard deviation change in average alcohol quantity, this is equivalent to an anxiety T-score increase of 0.3 (95% CI: 0.13, 0.48). The magnitude of this association did not change appreciably after adjusting for potential confounders. Associations of all lagged covariates with psychiatric problems are presented in Appendix C, Table C2. Table 5 presents results for tests of effect measure modification of the association between lagged alcohol quantity and anxiety problems by age, and Figure 2 shows the predicted values of anxiety problem T-scores associated with minimum, mean, and third-quartile levels of lagged alcohol quantity, over time. Adolescents show a decline in anxiety problems throughout adolescence, and little difference by the magnitude of fluctuations in lagged alcohol quantity. However, deviations arose at ages 13-14 and 17-19, where those who exhibited a mean or third-quartile level of increase in lagged alcohol quantity showed slower declines in anxiety problems compared to those who did not increase alcohol intake over time.

Table 4.

Changes in psychiatric problem T-scores associated with lagged changes in substance use frequency and quantity (N = 489)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | ||||||

| Affective | |||||||||||||||

| Marijuana frequency | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.003 |

| Alcohol frequency | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.002 | −0.0003 | −0.003 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.004 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.002 |

| Alcohol quantity | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| Anxiety | |||||||||||||||

| Marijuana frequency | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 | −0.0006 | −0.0030 | 0.0018 | −0.002 | −0.005 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 |

| Alcohol frequency | −0.0002 | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.0023 | 0.0043 | −0.002 | −0.01 | 0.002 | −0.0001 | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.004 |

| Alcohol quantity | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| Conduct | |||||||||||||||

| Marijuana frequency | 0.001 | 0 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.0003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | −0.0005 | 0.004 | 0.001 | −0.0005 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.0004 | 0.003 |

| Alcohol frequency | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.004 | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.004 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 |

| Alcohol quantity | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

Note. Separate models were run for affective, anxiety, and conduct problems. Model 1 for each exposure-outcome combination controls only for age trends using splines. Model 2 controls for age, prior SES, psychiatric problem domains that were not modeled as the outcome, and substance use measures that were not the exposure of interest. Model 3 controls for age and measures of prior parenting. Model 4 controls for age and measures of prior peer delinquency and drug use. Model 5 controls for age and covariates that were significant in the previous groups of confounder models. For affective problems: the marijuana frequency model controls for age and alcohol frequency. The alcohol frequency and quantity models do not differ from Model 1. For anxiety problems: the marijuana frequency model is the same as Model 1. The alcohol frequency and quantity models control for age and marijuana frequency. For conduct problems: the marijuana frequency, alcohol frequency, and alcohol quantity models are the same as Model 1. Estimates of all variables are included in Appendix C in the online supplement.

Table 5.

Age-related differences in the association between changes in lagged alcohol quantity and anxiety T-scores (N = 489)

| Alcohol quantity predicting changes in anxiety problems | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | ||

|

|

|||

| Alcohol quantity | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.61 |

| Age 13-14 | −2.30 | −3.15 | −1.45 |

| Age 15-16 | −4.22 | −5.30 | −3.15 |

| Age 17-19 | −4.88 | −5.53 | −4.22 |

| Alcohol quantity*Age 13-14 | −0.36 | −0.62 | −0.11 |

| Alcohol quantity*Age 15-16 | −0.26 | −0.84 | 0.32 |

| Alcohol quantity* Age 17-19 | −0.20 | −0.38 | −0.02 |

Figure 2.

Predicted anxiety problem T-score by age, given three levels of change in quantity of alcohol use. (N = 485)

Are the effects of psychiatric problems on substance use sensitive to timing?

This study focused on the longitudinal relationship between changes in psychiatric problems and changes in substance use one year later. However, the temporal resolution of this relationship may occur on a much shorter time frame – that is, changes in psychiatric problems may have immediate effects on substance use (or, changes in substance use may have immediate effects on psychiatric problems). To approximate effects on such a short time frame, we also examined the association between change in psychiatric problems and contemporaneous change in substance use. We followed the same modeling strategy as in our primary models, but adjusted for one-year-lagged versions of all covariates (except age). Table 6 presents the rate of contemporaneous changes in substance use frequency associated with changes in psychiatric problem T-score. In fully adjusted models, within-person changes in the conduct problems T-score were associated with contemporaneous changes in marijuana frequency, alcohol frequency, and alcohol quantity. Within-person changes in the affective problems T-score were associated with contemporaneous changes in alcohol quantity. Associations of all covariates with substance use in the contemporaneous models are presented in Appendix C, Table C3.

Table 6.

Contemporaneous changes in substance use frequency and quantity associated with changes in psychiatric problem T-scores (N=499)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | Rate Ratio | 95% CI | ||||||

| Marijuana frequency | |||||||||||||||

| Affective problems | 1.02 | 1 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 0.996 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 0.997 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.04 |

| Anxiety problems | 1.02 | 1 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 0.998 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.999 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.04 |

| Conduct problems | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 |

| Alcohol frequency | |||||||||||||||

| Affective problems | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.04 |

| Anxiety problems | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 |

| Conduct problems | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 |

| Alcohol quantity | |||||||||||||||

| Affective problems | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.004 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.004 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.004 | 1.03 |

| Anxiety problems | 1 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 |

| Conduct problems | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.05 |

Note. Separate models were run for affective, anxiety, and conduct problems. Model 1 for each exposure-outcome combination controls only for age trends using splines. Model 2 controls for age, prior SES, measures of prior substance use variables that were not modeled as the outcome, and measures of prior psychiatric problems that were not the exposure of interest. Model 3 controls for age and measures of prior parenting. Model 4 controls for age and measures of prior peer delinquency and drug use. Model 5 controls for age and covariates that were significant in the previous groups of confounder models. For marijuana frequency: The affective and anxiety problems models control for age, SES, alcohol frequency and quantity, and conduct problems. The conduct problems model control for age, SES, alcohol frequency, and alcohol quantity. For alcohol frequency: The affective, anxiety, and conduct problems models control for age and peer drug use. For alcohol quantity: The affective and anxiety problems models control for age, SES, marijuana frequency, and conduct problems. The conduct problems model controls for age and SES. Estimates of all variables are included in Appendix C in the online supplement.

Discussion

This study examined whether adolescent males tend to escalate their substance use following an increase in their psychiatric problems, and identified periods during adolescence when such associations may be particularly strong. We found that when youth experienced an increase in conduct problems, they showed an increase in the frequency of marijuana use and quantity of alcohol use in the following year. Fluctuations in conduct problems and affective problems may have an influence on alcohol use on a shorter time scale: changes in conduct problems and affective problems were concurrently associated with changes in alcohol frequency and quantity, respectively, in the same year, but not in the subsequent year. The specific effect of conduct problems on substance use is consistent with the notion that conduct disorder problems and substance use constitute elements within a broader externalizing spectrum.44,45

Although numerous longitudinal studies have demonstrated that youth with psychiatric problems are at increased risk for using and abusing substances (i.e., inter-individual difference), few have examined whether adolescents tend to increase their substance use following periods when they experience an increase in their psychiatric problems (i.e., intra-individual change).46,47 By focusing on within-individual change, we were able to rule out the possibility that selection effects and stable individual differences between youth with differing levels of psychiatric problems and substance use accounted for the observed association between psychiatric problems and substance use. Further, the use of an extensive set of measures of potential time-varying covariates (e.g., prior year changes in psychiatric problems, substance use, parenting characteristics, peer delinquency, and peer substance use), allayed concerns that the associations were confounded by time-varying factors. The strength of the associations between conduct disorder problems and marijuana and alcohol use were relatively modest, suggesting that a substantial change in conduct problems would have to occur to produce a substantial within-individual change in substance use. This is consistent with prior studies that have tried to predict change over time in substance use 10,48. Substance use is shaped by multiple risk factors working together – hence, any one risk factor is likely to make a modest contribution to within-individual fluctuations in substance use.

This study examined the bidirectional nature of the association between psychiatric problems and substance use, and found evidence of a reverse effect of substance use on psychiatric problems. While increases in anxiety and depression did not result in increases in substance use, increases in the quantity of alcohol use did result in increases in anxiety problems. The effect of alcohol use on anxiety problems is consistent with prior studies that have found that substance use increases the risk for anxiety disorders.49,50 There are at least two possible explanations for this observed pattern. First, substance use can increase exposure to economic and social problems that increase the risk for anxiety, including crime, unemployment, loss of income, and relationship problems.51 Second, substance use can cause neurochemical changes which increase vulnerability to an anxiety disorder.52

The effect of conduct disorder problem fluctuations on quantity of alcohol use was strongest in early adolescence, while the effect of conduct disorder changes on marijuana use was strongest in late adolescence (ages 17-19). At the same time, the effect of quantity of alcohol use on anxiety was strongest in early (ages 13-14) and late adolescence (ages 17-19). Two points are worth noting about this pattern. First, life transitions such as the shift from middle school to high school in early adolescence and the shift from high school to college in late adolescence may escalate existing challenges produced by fluctuations in psychiatric problems or substance use53,54. A few studies have examined shifts in substance use during these two turning points. For example, Jackson et al. found that the prevalence of heavy drinkers more than doubled in the transition to high school 55 and that this change was especially pronounced for youth with more problem behaviors. Studies of the transition from adolescence to young adulthood have also found that post-secondary school attendance predicted higher rates of substance use, and that the relationship between conduct problems and substance use was stronger in late adolescence than in middle adolescence,10,56-60 Pronounced effects of psychiatric problem and substance use fluctuations at times of transition would be consistent with an accentuation model 61, whereby the stress of the transition and the demands of the new context reduce contextual limitations on individual proclivities, potentially allowing for fluctuations in psychiatric problems to have a stronger effect on substance use, and vice versa. Second, the larger effect of conduct disorder on alcohol use at earlier ages and on marijuana use at later ages may reflect the developmental timing of these two substances. Drinking starts in early to mid-adolescence;62 hence, fluctuations in conduct problems in early adolescence may lead to involvement with alcohol use, as the drug that is most easily available in families and peer groups. In contrast, marijuana use typically starts in mid- to late-adolescence, so the influence of conduct problems on marijuana use may increase as access to marijuana becomes easier in later ages63

The study findings should be taken in light of the following limitations. First, all participants in the Pittsburgh Youth Study are male; hence, we could not examine the relationship between psychopathology and substance use quantity and frequency among girls. Second, all participants were selected from Pittsburgh public schools, which potentially limits the generalizability of the findings beyond this area. Third, half of the sample was composed of high-risk boys: this limited our ability to infer to the general population, but also provided us with greater power to detect an association between fluctuations in psychiatric problems and substance use. Fourth, while we examined measures of psychiatric problems that are consistent with DSM diagnoses, these measures did not explicitly measure diagnostic criteria for DSM disorders. Grouping symptoms into “affective”, “anxiety” and “conduct” problem categories might merge stronger individual disorders with non-predictors of substance use, leading to an underestimate of the association between psychiatric problems and substance use. However, it is increasingly recognized that psychiatric problems are best conceptualized as falling on a continuum of severity rather than representing a discrete taxon. Fifth, a low base rate prevented us from examining the predictors of fluctuation in the level of use of other illicit drugs. Sixth, the prevalence of marijuana use has increased since the completion of this study. Future studies should examine the impact that within-individual changes in psychiatric problems have on substance use in the current context.

Our study shows that when adolescent boys experience an increase in conduct disorder problems, they subsequently experience an increase in the quantity and frequency of substance use, while an increase in alcohol use can also subsequently result in increased anxiety problems in adolescence. Reducing fluctuations in conduct disorder problems and substance use at sensitive developmental turning points such as early and late adolescence may have lasting effects in preventing psychiatric and substance use problems by young adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Rebecca Stallings for her assistance with the data. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DA030449 (to M.C.), MH 082729 (to S.G), and MH078039 (to D.P.). Data collection was supported by grants awarded to Dr. Rolf Loeber from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA411018), National Institute on Mental Health (MH48890, MH50778), Pew Charitable Trusts, and Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (96-MU-FX-0012).

Footnotes

ETHICAL STATEMENT

- the material has not been published in whole or in part elsewhere;

- the paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere;

- all authors have been personally and actively involved in substantive work leading to the report, and will hold themselves jointly and individually responsible for its content;

- all relevant ethical safeguards have been met in relation to patient or subject protection, or animal experimentation.

Connection with tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical or gaming industry:

None of the authors have connections with the tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical or gaming industries. I testify to the accuracy of the above on behalf of all the authors.

Name: Magdalena Cerdá

Contributor Information

Dr. Magdalena Cerdá, Department of Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California.

Seth J. Prins, Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

Dr. Sandro Galea, Boston University School of Public Health.

Dr. Chanelle J. Howe, Department of Epidemiology, Brown University School of Public Health.

Dr. Dustin Pardini, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University.

References

- 1.Brook JS, Whiteman M, Finch SJ, Cohen P. Young adult drug use and delinquency: childhood antecedents and adolescent mediators. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(12):1584–1592. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galéra C, Bouvard M-P, Melchior M, et al. Disruptive symptoms in childhood and adolescence and early initiation of tobacco and cannabis use: the Gazel Youth study. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 2010;25(7):402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jester JM, Nigg JT, Buu A, et al. Trajectories of childhood aggression and inattention/hyperactivity: differential effects on substance abuse in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(10):1158–1165. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825a4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2004;99(12):1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lansford JE, Erath S, Yu T, Pettit GS, Dodge Ka, Bates JE. The developmental course of illicit substance use from age 12 to 22: links with depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders at age 18. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2008;49(8):877–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marmorstein NR. Longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems: The influence of comorbid delinquent behavior. Addictive behaviors. 2010;35(6):564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Jacob T, True W. The role of childhood risk factors in initiation of alcohol use and progression to alcohol dependence. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2007;102(2):216–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann P, Wittchen HU, Höfler M, Pfister H, Kessler RC, Lieb R. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders: a 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychological medicine. 2003;33(7):1211–1222. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cerdá M, Bordelois PM, Keyes KM, Galea S, Koenen KC, Pardini D. Cumulative and recent psychiatric symptoms as predictors of substance use onset: does timing matter? Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2013;108(12):2119–2128. doi: 10.1111/add.12323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maslowsky J, Schulenberg JE, Zucker Ra. Influence of conduct problems and depressive symptomatology on adolescent substance use: developmentally proximal versus distal effects. Developmental psychology. 2014;50(4):1179–1189. doi: 10.1037/a0035085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbons FX, Yeh H-C, Gerrard M, et al. Early experience with racial discrimination and conduct disorder as predictors of subsequent drug use: a critical period hypothesis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of general psychiatry. 2003;60(9):929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison PD. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Thousand Oaks: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2010;196(6):440–446. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2009;66(3):260–266. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM, Coffey C, et al. Cannabis and depression: an integrative data analysis of four Australasian cohorts. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2012;126(3):369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loeber R, Farrington D, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Raskin White H, Wei E. Violence and Serious Theft: Development and Prediction from Childhood to Adulthood. New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeber R, Menting B, Lynam DR, et al. Findings from the Pittsburgh youth study: Cognitive impulsivity and intelligence as predictors of the age-crime curve. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:1136–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardini DA, Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Identifying direct protective factors for nonviolence. American journal of preventive medicine. 2012;43(2):S28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.024. Suppl 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, White HR. Developmental aspects of delinquency and internalizing problems and their association with persistent juvenile substance use between ages 7 and 18. Journal of clinical child psychology. 1999;28:322–332. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/ 4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington,VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington,VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achenbach TM. Young Adult Self Report. Burlington,VT: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Achenbach T, Dumenci L, Rescorla L. Ratings of relations between DSM-IV diagnostic categories and items of the CBCL/6-18, TRF, and YSR. University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achenbach TM. Integrative Guide to the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington,VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferdinand RF. Validity of the CBCL/YSR DSM-IV scales Anxiety Problems and Affective Problems. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;(22):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achenbach T. Integrative Guide to the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrington DP. Explaining the link between problem drinking and delinquency. Addiction. 1996;91(4):498–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1996.tb02304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller DS, Miller TQ. A test of socioeconomic status as a predictor of initial marijuana use. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Family factors as correlates and predictors of juvenile conduct problems and delinquency. In: Tonry M, Morris N, editors. Crime and justice: An annual review of research. Vol. 7. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moos RH, Moos BS. Evaluating correctional and community settings. In: Moos RH, editor. Families. Wiley; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skinner HA, Steinhauer PD, Santa-Barbara J. The family assessment measure. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 1983;2:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice : Multivariate Imputation by Chained. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45(3) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lumely Thomas. 'mitools': Tools to perform analyses and combine results from multiple-imputation datasets. 2013 http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mitools/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation After 18+ Years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91(434):473. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ver Hoef J, Boveng P. Quasi-Poisson vs. negative binomial regression: how should we model overdispersed count data? Ecology. 2007;88(11):2766–2772. doi: 10.1890/07-0043.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeileis A, Kleiber C, Jackman S. Regression Models for Count Data in R. Journal Of Statistical Software. 2008;27:1076–1084. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allison PD. Fixed Effects Regression Methods for Longitudinal Data Using SAS. Cary, NC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Statistics in medicine. 1989;8(5):551–561. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG. Etiologic Connections Among Substance Dependence, Antisocial Behavior, and Personality: Modeling the Externalizing Spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(3):411–424. M M. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Benning SD, Kramer MD. Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: an integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116(4):645–666. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual review of psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yen S, Stout R, Hower H, et al. The influence of comorbid disorders on the episodicity of bipolar disorder in youth. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2015. Early View. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Henry KL, Thornberry TP. Truancy and escalation of substance use during adolescence. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2010;71(1):115–124. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fergusson D, Boden J, Horwood L. Structural models of the comorbidity of internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in a longitudinal birth cohort. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46:933–942. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patton GC, Hibbert M, Rosier MJ, Carlin JB, Caust J, Bowes G. Is smoking associated with depression and anxiety in teenagers? American journal of public health. 1996;86(2):225–230. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macleod J, Oakes R, Copello A, et al. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(2):149–171. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulenberg JE, Zarrett NR, Arnett JJ, Tanner JL. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: 2006. Mental Health During Emerging Adulthood : Continuity and Discontinuity in Courses, Causes, and Functions; pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, Maslowsky J, Maggs J, Lewis M, Rudolph K. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. 3rd New York, NY: 2014. The epidemiology and etiology of adolescent substance use in developmental perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jackson KM, Schulenberg JE. Alcohol use during the transition from middle school to high school: national panel data on prevalence and moderators. Developmental psychology. 2013;49(11):2147–2158. doi: 10.1037/a0031843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impact of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Bryant AL, Merline AC. The decline of substance use in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs. Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of studies on alcohol. Supplement. 2002;(14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staff J, Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, et al. Substance use changes and social role transitions: proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Development and psychopathology. 2010;22(4):917–932. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lune LSV, Wills TA, Brody G, Conger RD. Context and cognitions: Environmental risk, social influence, and adolescent substance use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30(8):1048–1061. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caspi A. The child is father of the man: Personality continuities from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78(1):158–172. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Newes-Adeyi G, Chen C, Williams G, Faden V. Surveillance Report #74: Trends in Underage Drinking in the United States, 1991-2003. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gfroerer J, Wu L-T, Penne M. Initiation of Marijuana Use: Trends,Patterns, and Implications (Analytic Series: A-17, DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3711) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Serfvices Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.