Abstract

Non-histaminergic TRPA1 neural pathway is required for the development of allergic ocular itch. Pharmacological inhibition of TRPA1 channel can lead to novel therapeutic strategies to treat ocular itch in severe allergic conjunctivitis.

Keywords: allergic conjunctivitis, ocular itch, histamine-independent, TRPA1, platelet-activating factor

To the Editor

Itch is the cardinal symptom of allergic conjunctivitis and afflicts 15–20% of the population worldwide. Histamine produced by conjunctival mast cells has been implicated as the principal itch mediator that activates histamine receptors on primary sensory fibers to induce allergic ocular itch1. However, antihistamines cannot completely relieve ocular itch in many cases, suggesting the involvement of a histamine-independent itch pathway. Herein, we sought to identify the histamine-independent neural pathway involved in allergic conjunctivitis and to develop new therapeutic strategies for allergic ocular itch.

Allergic ocular itch typically originates from the conjunctiva, a mucosal membrane that is anatomically distinct from the skin and covers the ocular surface over sclera and the inner surface of the eyelid. However, our knowledge about the neural regulations of allergic ocular itch and its difference from skin itch is limited. Mast cells have been shown to secrete many bioactive compounds in addition to histamine2, 3. Yet, it remains unclear regarding the contribution of histamine-independent mediators to allergic ocular itch in comparison to histamine, and the neural pathway mediating the histamine-independent components in ocular itch. TRPA1 is a cation channel that is often co-localized with TRPV1 in a subpopulation of primary sensory neurons in the trigeminal ganglion (TG) and dorsal root ganglion. While TRPV1 is known to be the downstream transduction channel of histamine H1 receptor in sensory neurons4, TRPA1 was recently found to be the downstream transduction channel of histamine-independent itch in the skin5. However, it is yet unknown whether TRPA1 is required for mast cell-mediated allergic itch. In this study, we characterized the role of TRPA1 as a histamine-independent modulator in ocular itch associated with allergic conjunctivitis.

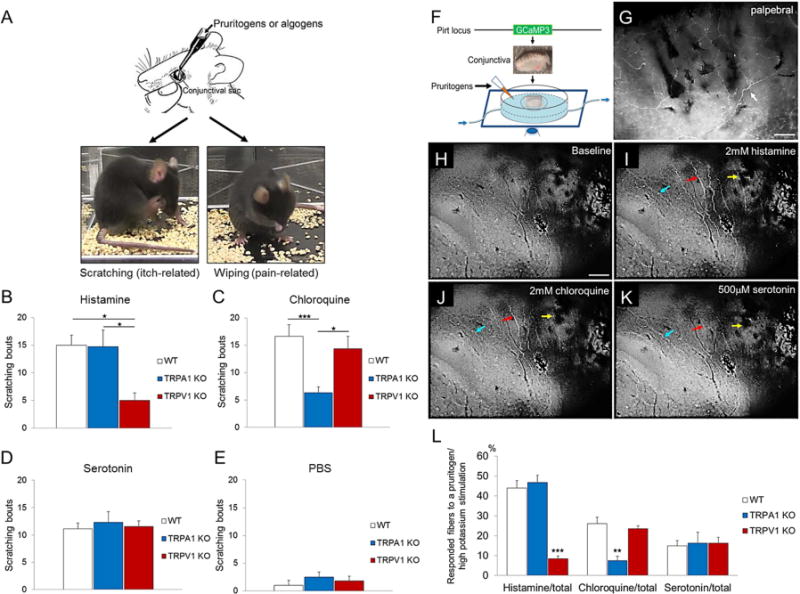

To delineate the respective role of TRPA1 and TRPV1 in ocular itch, we first examined the acute behavioral responses of wild type (WT), TRPA1 knockout (KO), and TRPV1 KO mice to pruritogens applied directly to their lower conjunctival sacs. We were able to differentiate ocular itch from pain using our behavioral models, in which itch-inducing compounds provoked mice to scratch the treated area using their hindpaw, while pain-inducing capsaicin elicited wiping behavior using the forelimb (Fig 1, A). We found that histamine challenge (46 μg in 2.5 μl PBS) induced 15±1.8 scratching bouts in WT and 14.7±3 bouts in TRPA1 KO (Fig 1, B), but significantly less itch responses in TRPV1 KO (5±1.3 bouts), suggesting that TRPV1–rather than TRPA1− is responsible for histamine-dependent ocular itch signaling. We then tested two histamine-independent pruritogens, chloroquine and serotonin on evoking ocular itch. Chloroquine-induced (12.4 μg) ocular scratching was significantly decreased in TRPA1 KO (6.3±1.1 bouts), compared to WT (16.6±2 bouts) and TRPV1 KO (14.3±2.3 bouts) (Fig 1, C), indicating that TRPA1 is required for histamine-independent itch induced by chloroquine. In contrast, there was no difference in ocular itch responses induced by serotonin (0.2 μg) among WT (11.1±1.1 bouts), TRPA1 KO (12.3±1.0 bouts) and TRPV1 KO (11.6±1 bouts) (Fig 1, D). Vehicle control (PBS) only induced minimal scratching responses (Fig 1, E). These behavioral results indicate a pivotal role of TRPA1 in certain types of non-histaminergic ocular itch.

Fig 1.

Behavioral and cellular mechanisms of pruritogen-induced ocular itch. A, Behavioral distinction between ocular itch and pain in mice. B, Histamine-evoked scratching responses were reduced in TRPV1 KO. n=5–9 per group. C, Chloroquine-induced scratching behavior was attenuated in TRPA1 KO. n=6–13 per group. D, Serotonin evoked comparable number of scratching bouts among three genotypes. n=7–14 per group. E, PBS elicited minimal and significantly less scratching responses than any group receiving pruritogen-challenge. n=5–9 per group. F, Imaging conjunctival nerve fiber activities using Pirt-GCaMP3 mouse. G, Whole-mount immunofluorescence of GCaMP3 signal in a PirtGCaMP3/+ conjunctiva. White arrow, GCaMP3+ sensory fiber. H–K, Responses of sensory fibers to pruritogens. Arrows in different colors indicate conjunctival fibers with differential receptivity to pruritogens. L, Percentage of GCaMP3+ conjunctival fibers activated by pruritogens among PirtGCaMP3/+, TRPA1 KO; PirtGCaMP3/+, and TRPV1 KO; PirtGCaMP3/+ mice. n≥5 per group. Scale bar represents 100μm. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

To further explore the underlying mechanisms, we examined whether TRPA1 is functionally required for the responsiveness of conjunctival sensory fibers to pruritogens. We found conjunctival mucosa is abundantly innervated by TRPA1+ and TRPV1+ neurons, but not cold-sensing TRPM8+ neurons in TG (Fig E1). GCaMP3-assisted calcium imaging of conjunctival sensory fibers showed that upon stimulation by pruritogens, subpopulations of conjunctival nerve fibers displayed moderate to high calcium mobilization (Fig 1, F–K). Interestingly, TRPA1 deficiency does not affect conjunctival nerve response to histamine stimulation, but significantly reduces the nerve response to chloroquine stimulation. In contrast, TRPV1 is required for nerve fiber response to histamine but not chloroquine in the conjunctiva. Finally, deficiency in TRPA1 or TRPV1 did not affect serotonin-induced nerve activity (Fig 1, L). These data reveal a segregation of TRPA1-dependent and TRPV1-dependent pathways in conjunctiva-innervating sensory neurons.

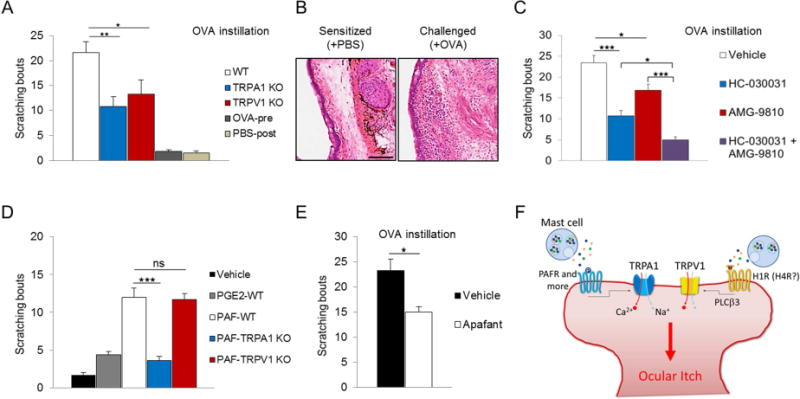

Involvement of TRPA1-mediated itch pathway in allergic ocular itch was next evaluated using an ocular allergy model. Mast cell-mediated allergic conjunctivitis was induced in mice using an ovalbumin (OVA) sensitization regime (Online Methods). Topical OVA challenge (250 μg) into unilateral conjunctival sac provoked targeted scratching responses in WT (21.6±2.1 bouts, Fig 2, A). This itch was caused by allergen (OVA)-specific immune reaction, as OVA challenge before sensitization or vehicle treatment after sensitization did not elicit significant scratching responses (Fig 2, A). More importantly, our allergic conjunctivitis model recapitulates histological changes associated with severe seasonal allergy or atopic keratoconjunctivitis in humans6, as evidenced by our serial OVA challenges leading to inflammatory cells infiltrations and loss of goblet cells in the conjunctiva (Fig 2, B). Interestingly, in this model, ocular itch was significantly attenuated in TRPA1 KO (10.8±1.9 bouts), and TRPV1 KO (13.3±2.9 bouts), suggesting that both TRPA1 and TRPV1 are required for allergic ocular itch. The observed behavioral changes were not due to defects in mast cell activation of TRPA1 KO or TRPV1 KO, as mast cell degranulation was comparable among WT, TRPA1 KO and TRPV1 KO (Fig E2).

Fig 2.

Involvement of TRPA1 and TRPV1 in ocular itch of mast cell-dependent allergic conjunctivitis. A, Comparison of scratching behavior among ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized WT, TRPA1 KO and TRPV1 KO in response to conjunctival OVA challenge. n=10–16 per group. B, Inflammatory cell infiltration and loss of goblet cell in allergic conjunctiva due to repeated OVA challenges. C, Pharmacological antagonism of TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels effectively attenuates ocular itch induced by allergic conjunctivitis. n=6–9 per group. D, Comparison of scratching behavior in response to conjunctival PGE2 or PAF challenge. n=6–12 per group. E, Topical Apafant alleviates allergic ocular itch. n=8 per group. F, Synergistic activation of TRPA1 and TRPV1 by mast cell mediators confers ocular itch in allergic conjunctivitis. Scale bar represents 100μm. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

To further explore the potential of TRPA1 as a therapeutic target for allergic conjunctivitis, we examined the effect of pharmacologically blocking TRPA1 in ocular allergy. Compared to vehicle-treated group (23.4±1.7 bouts), pretreatment with TRPA1 antagonist HC-030031 significantly alleviated allergic ocular itch in mice (10.7±1.3 scratching bouts). More importantly, combined treatment of TRPA1 and TRPV1 antagonists abolished scratching responses to OVA challenge (Fig 2, C), indicating that the TRPA1 pathway complements the TRPV1 pathway in allergic ocular itch, and that combined pharmacological antagonism of TRPA1 and TRPV1 can be an effective and novel therapeutic strategy for allergy-induced ocular itch.

Finally, we investigated potential endogenous histamine-independent itch mediators in ocular allergy. Platelet activating factor (PAF) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) are key inflammatory factors released by mast cells during allergic reaction, and have been shown to cause ocular itch in guinea pigs7–9. Following this line of evidence, we found that topical PAF challenge evoked strong scratching responses (12±1.2 bouts), but PGE2 only induced very mild itch in mice (4.4±0.4 bouts) (Fig 2, D). Interestingly, PAF-induced ocular scratching was reduced in TRPA1 KO but not TRPV1 KO, suggesting that TRPA1 is required for PAF-induced itch (Fig 2, D). Indeed, GCaMP3-assisted calcium imaging demonstrated direct activation of a small population of TG neurons by PAF in the presence of TRPA1 (Fig E3).To determine whether PAF is involved in allergic ocular itch, mice were pretreated with Apafant, a specific PAF receptor antagonist. Apafant significantly alleviated itch in mice with allergic conjunctivitis (Fig 2, E), substantiating the involvement of PAF in ocular allergic itch. Taken together, our data suggest that PAF is one of the upstream itch-mediators for histamine-independent TRPA1 pathway in allergic ocular itch.

The essential role of TRPA1 in allergic ocular itch prompted us to ask whether TRPA1 plays a similar role in allergic skin itch. Allergic skin itch was only marginally reduced in TRPA1 KO mice (154.3±16.1 bouts) compared with WT (206±17.5). Surprisingly, allergic skin itch was not significantly reduced in TRPV1 KO mice (179.4±28.0), arguing against a critical role of histamine-dependent pathway in this model of skin itch. Our data reveals the first disparity between skin and ocular itch. (For further information, please see online information in Fig E4).

Taken together, our results suggest that histamine-independent signaling is equally important as histamine-dependent signaling to mediate ocular itch in allergic conjunctivitis. Current therapeutic strategies for ocular itch management rely heavily on antihistamines and immune-suppressive drugs, and often have limited efficacy. Long-term use of these drugs may be associated with increased risks for ocular complications such as dry eye, glaucoma, and cataract1, E1–5. TRPA1 can potentially serve as a novel therapeutic target for more effective management of allergic ocular itch, especially in cases refractory to conventional treatments. More importantly, our data also imply targeting both TRPA1 and TRPV1 may achieve an even better and synergistic therapeutic outcome for ocular-itch (Fig 2, F), while circumventing untoward effects of current anti-ocular itch therapies.

We are grateful to Drs. David C. Beebe, Hongzhen Hu, Brian S. Kim, Zhou-Feng Chen, and Todd P. Margolis for insightful discussions and comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Xinzhong Dong for sharing PirtGCaMP3/+ mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01EY024704 to Q.L.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ono SJ, Abelson MB. Allergic conjunctivitis: update on pathophysiology and prospects for future treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:118–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metcalfe DD, Baram D, Mekori YA. Mast cells. Physiological reviews. 1997;77:1033–79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raap U, Stander S, Metz M. Pathophysiology of itch and new treatments. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2011;11:420–7. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834a41c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shim WS, Tak MH, Lee MH, Kim M, Kim M, Koo JY, et al. TRPV1 mediates histamine-induced itching via the activation of phospholipase A2 and 12-lipoxygenase. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2331–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4643-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson SR, Gerhold KA, Bifolck-Fisher A, Liu Q, Patel KN, Dong X, et al. TRPA1 is required for histamine-independent, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor-mediated itch. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:595–602. doi: 10.1038/nn.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu Y, Matsumoto Y, Dogru M, Okada N, Igarashi A, Fukagawa K, et al. The differences of tear function and ocular surface findings in patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis and vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Allergy. 2007;62:917–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galli SJ, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:445–54. doi: 10.1038/nature07204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill P, Jindal NL, Jagdis A, Vadas P. Platelets in the immune response: Revisiting platelet-activating factor in anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1424–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodward DF, Nieves AL, Spada CS, Williams LS, Tuckett RP. Characterization of a behavioral model for peripherally evoked itch suggests platelet-activating factor as a potent pruritogen. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:758–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.