Abstract

Background

Antibody therapeutic targeting of the immune checkpoints cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated molecule 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) has demonstrated marked tumor regression in clinical trials. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) can modulate multiple gene transcripts including possibly more than one immune checkpoint and could be exploited as immune therapeutics.

Methods

Using online miRNA targeting prediction algorithms, we searched for miRNAs that were predicted to target both PD-1 and CTLA-4. MiR-138 emerged as a leading candidate. The effects of miR-138 on CTLA-4 and PD-1 expression and function in T cells were determined and the therapeutic effect of intravenous administration of miR-138 was investigated in both immune-competent and -incompetent murine models of GL261 glioma.

Results

Target binding algorithms predicted that miR-138 could bind the 3′ untranslated regions of CTLA-4 and PD-1, which was confirmed with luciferase expression assays. Transfection of human CD4+ T cells with miR-138 suppressed expression of CTLA-4, PD-1, and Forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) in transfected human CD4+ T cells. In vivo miR-138 treatment of GL261 gliomas in immune-competent mice demonstrated marked tumor regression, a 43% increase in median survival time (P = .011), and an associated decrease in intratumoral FoxP3+ regulatory T cells, CTLA-4, and PD-1 expression. This treatment effect was lost in nude immune-incompetent mice and with depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, and miR-138 had no suppressive effect on glioma cells when treated directly at physiological in vivo doses.

Conclusions

MiR-138 exerts anti-glioma efficacy by targeting immune checkpoints which may have rapid translational potential as a novel immunotherapeutic agent.

Keywords: CTLA-4, glioblastoma, microRNAs, miR-138, PD-1

Despite advances in treatment of many malignancies, glioblastoma remains a vexing clinical problem, with a median survival time of 12–15 months.1,2 MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, noncoding RNAs that act as regulators of diverse biological processes and regulate gene expression by forming imperfect base pairing with sequences in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR), which prevents protein expression by repressing translation or inducing mRNA degradation.3 MiRNAs have been of particular interest in cancers, due to their differential expression in malignant tissues. Several miRNA libraries have been explored in the function of glioblastoma, and a variety of miRNAs have been identified that are either significantly upregulated or downregulated.4,5 One of the vexing therapeutic issues has been delivery of the miRNA into solid tumors. By using miRNAs to target systemic tumor-mediated immune suppression, immune effector cytotoxic responses could then exert therapeutic activity against the glioblastoma.

Immune evasion and suppression created by the glioblastoma itself are primary factors preventing current immunotherapies from effectively fighting glioblastoma. Glioblastoma creates an immunosuppressive microenvironment within the brain, facilitating the growth and malignant properties of the lesion while evading the body's immune system.6–8 Thus, there is significant interest in using immune therapeutics to counteract these effects in glioblastoma.9

The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated molecule 4 (CTLA-4) is a negative regulator of T-cell activation and an inducer of Forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) and regulatory T-cell (Treg) suppressor activity. Targeting CTLA-4 in immune-competent clonotypic murine model systems of intracerebral glioma has demonstrated marked improvement in median survival time.10 Furthermore, therapeutic targeting of CTLA-4 in advanced-stage melanoma patients has resulted in FDA approval of the monoclonal antibody (mAb) ipilimumab.11 Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and its ligand, programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), mediate the immunosuppressive effects of tumors by promoting T-cell apoptosis and the induction of Tregs.12 Similarly to CTLA-4, antibody therapy targeting PD-L1 and PD-1 has been shown to exert antitumor effects by reversing the immunosuppressive effects of PD-1.13 The ligand PD-L1 has been observed to be overexpressed in glioblastomas and glioblastoma-associated macrophages.14–16 Nivolumab, an mAb to PD-1, has also demonstrated marked radiographic and therapeutic responses in phase I clinical trials of patients with advanced malignancy.17,18 Most recently, ipilimumab coadministered with nivolumab in melanoma patients demonstrated an objective response rate of 47%,19 showing that targeting both of these immune checkpoints can result in a potent synergy. Given the heterogeneity of PD-1 and CTLA-4 expression in glioblastoma,20 a therapeutic that can target both would potentially benefit a greater percentage of patients.

MicroRNA 138 (miR-138) has been shown to regulate a number of biological processes, including embryological morphogenesis and developmental events tied to stem cell differentiation.21 MiR-138 is enriched in the brain and is associated with the regulation of dendritic spine morphogenesis in rat hippocampal neurons.22 In multiple cancers, miR-138 has been shown to be downregulated and to serve as a tumor suppressor.23–26 Although it is clear that miR-138 has a multifaceted role in carcinoma, its ability to interact with the immune system is unknown. Our own preliminary analysis of the structure of miR-138 indicated binding homology with both CTLA-4 and PD-1. We have previously shown that miRNAs delivered into the blood can be enriched in the mononuclear compartment .27 Therefore, we hypothesized that by interacting with CTLA-4 and PD-1, miR-138 could regulate Tregs and that administration of miR-138 in vivo could exert potent antitumor immune effects.

Materials and Methods

Additional detailed methods can be found in the Supplementary material.

Cell Lines

The HeLa cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection, and the murine glioma GL261 cell line was kindly provided by Dr Bozena Kaminska of Warsaw, Poland.28 These cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Life Technologies), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies), and 1% l-glutamine (Life Technologies). The B16 cells were kindly provided by Dr Willem Overwijk at MD Anderson and were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The cell cultures were split (1:2) every 3 days to ensure logarithmic growth.

Luciferase Assay

To determine whether miR-138 can bind to the 3′ UTR of CTLA-4 and/or PD-1, HeLa cells were cotransfected with the designated luciferase reporter plasmid (CTLA-4, pMirTarget, Origene; PD-1, miTarget, Genecopoeia) and miR-138 or control miRNA precursor molecules (pre-miR, Life Technologies) with Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). Further details of this analysis can be found in the Supplementary material.

Functional Analysis of Human T Cells

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells purified from healthy donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) at 0.5 million/mL were added to anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibody (BD Biosciences) pre-bound 24-well plates for 48 h for T-cell activation and proliferation, either with or without the addition of 5 ng/mL transforming growth factor (TGF) β1. Additionally the cells were transfected with vectors expressing either miR-138 or scramble RNA via the nucleofector human T-cell transfection kit (Lonza). CD4+CD25+ natural Tregs (nTregs) were sorted by a FACSAria cell sorter (Becton Dickinson) and were transfected with either miR-138 or the scramble control while being stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 48 h. Immune cell subsets were surface stained with antibodies to PD-1 (conjugated to peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCP; eBioscience]), and CTLA-4 (conjugated to phycoerythrin [PE; Becton Dickinson]) and CD4+ cells were further permeabilized for intracellular staining of FoxP3 (conjugated to allophycocyanin [APC; eBioscience]) or inducible co-stimulator (ICOS; conjugated to APC; eBioscience 17-9948-42). Samples were then evaluated by flow cytometry. The use of healthy donor PBMCs was approved by the institutional review board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and conducted under protocol LAB03-0687.

In vivo Experiments

The miR-138 duplex that mimics pre-miR-138 (sense: 5′-AGCUGGUGUUGUGAAUCAGGCCGU-3′, antisense: 5′-GGCCUGAUUCACAACACCAGCUGC-3′) and the scramble control miRNA duplex (sense: 5′-AGUACUGCUUACGAUACGGTT-3′, antisense: 5′-CCGUAUCGUAAGCAG UACUTT-3′) were synthesized (SynGen). The scramble control sequence was picked due to its comparable length and composition to miR-138 and because it does not have binding sites to any known 3′ UTRs, including those within CTLA-4 and PD-1. The sequence of murine miR-138 is identical to human miR-138 on the basis of data from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The treatment cohorts consisted of 2 µL miR-138 or scramble control (10 µg/µL) + 48 µL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) mixed with the vehicle (40 µL PBS + 10 µL Lipofectamine 2000) or the vehicle control (90 µL PBS + 10 µL Lipofectamine 2000). C57BL/6J mice and athymic nude mice were purchased from the Department of Experimental Radiation and Oncology of MD Anderson. For tumor injections, the mice were anesthetized with a single dose of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Mice were maintained in the MD Anderson Isolation Facility in accordance with Laboratory Animal Resources Commission standards and treated according to the approved protocol 08-06-11831.

Syngeneic Subcutaneous Model

To induce subcutaneous tumors, logarithmically growing GL261 cells were injected into the right hind flanks of 6-week-old C57BL/6J female mice or nude mice at a dose of 1 × 106 cells suspended in 100 µL PBS-diluted Matrigel basement membrane matrix (BD Biosciences) (PBS:Matrigel = 2:1). When palpable tumors (∼0.5 cm in maximum diameter) formed, the mice (n = 5/group) were treated by intravenous injection. Tumors were measured twice a week. Mice that showed signs of morbidity, high tumor burden, or skin necrosis were immediately compassionately killed according to MD Anderson guidelines. Tumor volume was calculated with slide calipers using the following formula: V = (L × W × H)/2, where V is volume (mm3), L is the long diameter, W is the short diameter, and H is the height.

Syngeneic Intracranial Glioma Model

To induce intracerebral tumors in C57BL/6J mice and athymic nude mice, GL261 cells or B16 cells were injected into the cerebrum. These cells were collected in logarithmic growth phase, washed twice with PBS, mixed with an equal volume of 10% methyl cellulose in Improved modified Eagle's Zinc Option medium, and loaded into a 250-μL syringe (Hamilton), with an attached 25-gauge needle. The mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The needle was positioned 2 mm to the right of bregma and 4 mm below the surface of the skull at the coronal suture using a stereotactic frame (Kopf Instruments), as we have previously described29. The intracerebral tumorigenic dose for GL261 cells was 5 × 104 and for B16, 5 × 102 in a total volume of 5 μL. Mice were then randomly assigned to control and treatment groups (n = 8–10/group for GL261, n = 6–7/group for B16). Animals were observed 3 times per week, and when they showed signs of neurological deficit (lethargy, failure to ambulate, lack of feeding, or loss of >20% body weight), they were compassionately killed. These symptoms typically occurred within 48 h before death. Their brains were removed and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin.

In vivo Depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells

For the in vivo depletion studies, each mouse was injected i.p. with 0.4 mg rat anti-mouse CD8 (53-6.7), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), or normal immunoglobulin G isotype as control antibody (all from Bio X Cell) in 200 μL PBS one day prior to GL261 tumor i.c. implantation. The second dose was on the same day that the miR-138 treatment began, followed by 2 more daily administrations, and then twice a week for 2 additional weeks. Maintenance of the in vivo depletion throughout the experimental period was confirmed by flow cytometry of PBMCs with APC anti-mouse CD4 (RM4-5) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-mouse CD8α (53-6.7) (BD Biosciences).

Immunohistochemical Analysis of Treated Murine Gliomas

Please see the Supplementary material for details of FoxP3 immunohistochemistry.

Ex vivo Murine Immune Analysis

An ex vivo expression analysis of PD-1 and CTLA-4 on CD4 T cells was carried out during the therapeutic window presented by our treatment of GL261 tumors with either scramble control or miR-138. For the subcutaneous tumor model, GL261 cells were injected into the right hind flanks of C57BL/6J female mice at a dose of 2 × 106 cells suspended in 100 µL PBS-diluted Matrigel basement membrane matrix (BD Biosciences) (PBS:Matrigel = 2:1, volume ratio). After palpable tumors were noted on the 9th day, intravenous treatment with either miR-138 or scramble control was initiated on a Monday, Wednesday, and Friday schedule. On the 10th day after treatment, their subcutaneous tumors were harvested (n = 5/group). Single-cell suspensions were obtained from the tumors. For the intracranial tumor model, 5 × 104 GL261 cells were implanted into C57BL/6J mouse brains as described in the previous section, and then miR-138 or scramble control treatment was followed on a Monday, Wednesday, and Friday schedule. On the 17th day after treatment, brain tumor tissues were pooled together from each group (miR-138 or scramble, n = 10/group) and were digested with the Neural Tissue Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech) followed by myelin removal by Myelin Removal Beads II (Miltenyi Biotech), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were stained for PerCP anti-CD4 (clone: GK1.5), PE anti-CTLA-4 (clone: UC10-4F10-11), and APC anti-PD-1 (clone: J43) (all from BD Pharmingen), and were then subgated on CD4 for CTLA-4 and PD-1 expression analysis. To detect FoxP3 protein expression, the CD4 surface-stained cells were further subjected to intracellular staining with FITC-conjugated mAb to mouse FoxP3 (clone: FJK-16s; eBioscience) using staining buffers and conditions specified by the manufacturer. Control isotype antibodies were used to establish gating and were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Statistics

For all survival analyses, Kaplan–Meier curves were generated via GraphPad Prism 6 software, and significance was evaluated using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. An ANOVA, 2-sided 2-sample test, or paired t-test, as appropriate, was used for all other data comparisons using GraphPad Prism 6 software. A threshold of P < .05 was used to determine significance in each experiment.

Results

Screening and Prioritization of MiRNA Candidates to Target Immune Checkpoints

Candidate miRNAs that could potentially target both CTLA-4 and PD-1 were screened using RNA22 and miRanda (Supplementary Table S1). Prioritization was selected based on predicted binding of both PD-1 and CTLA-4 and on multiple sites of potential binding increasing the propensity of being biologically meaningful. Because miR-138 had the most predicted binding sites, and has been previously implicated as being downregulated in the glioblastoma microenvironment,27 it was selected for further development. It is also predicted to target the 3′ UTRs of murine PD-1 and CTLA-4, allowing us to test the therapeutic effect of this approach in a murine model system.

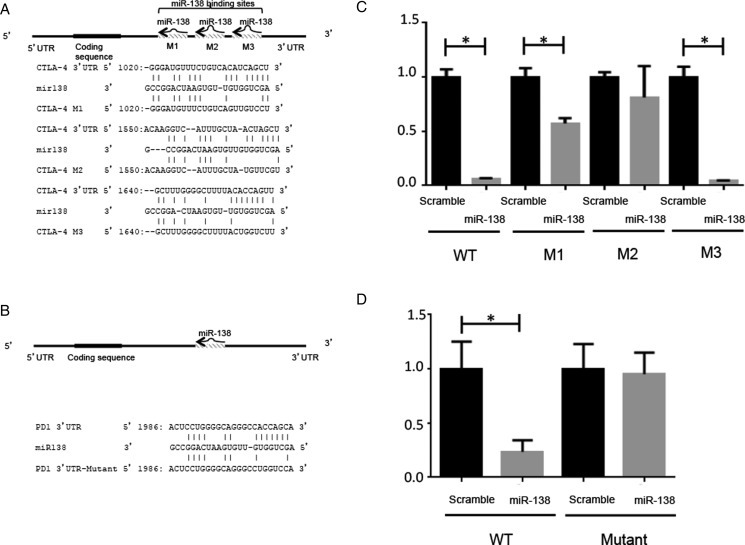

MiR-138 Targets Immune Checkpoints

Using RNA22 and miRanda, we searched for miRNAs that were predicted to bind the key immune checkpoints CTLA-4 and PD-1. MiR-138 emerged as a leading candidate with 3 predicted binding sites in the 3′ UTR of CTLA-4 and 1 within PD-1 (Fig. 1). To functionally verify these targets, luciferase expression assays were conducted, including mutating the predicted 3′ UTRs of the CTLA-4 and PD-1 binding sites of miR-138 (Fig. 1A and B). In cotransfected HeLa cells, 2 of the 3 mutated miR-138 binding sites of the 3′ UTR of CTLA-4 resulted in diminished luciferase activity relative to baseline (Fig. 1C). PD-1 luciferase activity was significantly inhibited by miR-138, whereas mutational alteration of the miR-138 binding site of the 3′ UTR of PD-1 abolished the inhibitory effect of miR-138 on luciferase expression (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

MiR-138 binds the 3′ UTRs of CTLA-4 and PD-1. (A) The 3 predicted miR-138 binding sites in the 3′ UTR of CTLA-4 are noted with their sequences. The mutational alterations are noted for each luciferase expression construct. (B) The miR-138 binding site sequence of the 3′ UTR of PD-1 and its mutant in the luciferase expression construct are noted. (C) The relative luciferase expression in HeLa cells transfected with miR-138 pre-miR versus scramble control pre-miR is shown. A significant decrease in luciferase expression is seen when the cells are cotransfected with a reporter plasmid containing the wild-type 3′ UTR of CTLA-4 and miR-138 pre-miR. The M3 mutation appears to have no effect, whereas the M1 mutation reduces the modulation of the miR-138 pre-miR, and the M2 mutation completely abolishes the significant effect of the miR-138 pre-miR, implying that the M2 binding site is the most critical. *P < .05. (D) A significant decrease in luciferase expression is seen when the cells are cotransfected with a reporter plasmid containing the wild-type 3′ UTR of PD-1 and miR-138, whereas this difference is abolished when the mutant 3′ UTR reporter plasmid is evaluated. *P < .05.

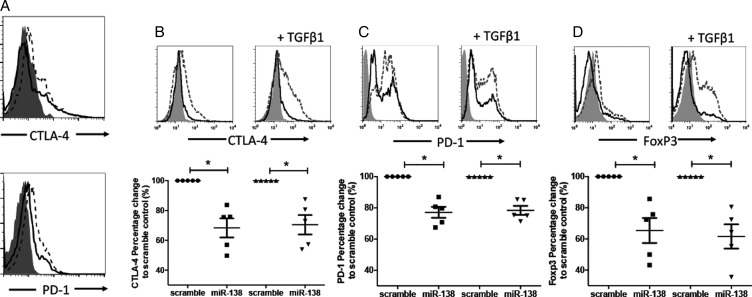

MiR-138 Inhibits Tregs by Targeting Immune Checkpoints

Intrinsic miR-138 levels are negligible in human naïve and activated T cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). To begin to functionally assess the immunological modulatory effects of miR-138, nTregs were isolated from healthy donors and were transfected with miR-138. MiR-138 induced a modest decrease in CTLA-4 and PD-1 expression relative to cells transfected with scramble control miRNA (Fig. 2A). Next, we asked whether miR-138 could block the induction of immune checkpoint expression during the activation of CD4+ T cells as well as in the setting of TGF-β1–mediated immune suppression. CD4+ T cells transfected with miR-138, with or without TGF-β Treg induction, had downregulated CTLA-4, PD-1, and FoxP3 expression compared with the scramble control (Fig. 2B–D). Identical results were obtained with the CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. S2A).

Fig. 2.

MiR-138 inhibits human checkpoint expression in Tregs. (A) CD4+CD25+ Tregs isolated from healthy donor murine splenocytes by fluorescence activated cell sorting were observed to have both CTLA-4 and PD-1 downregulation when transfected with miR-138 compared with scramble control (n = 4). Summary data dot plots are shown below the T-cell histograms. (B–D) Healthy donor human CD4+ T cells were stimulated by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 48 h in the absence or presence of TGF-β to induce CTLA-4, PD-1, and FoxP3+ Tregs and subsequently transfected with miR-138 pre-miR or scramble control. MiR-138 downmodulated the expression of (B) CTLA-4, (C) PD-1, and (D) FoxP3 in CD4+ T cells. The solid-gray histogram is the isotype control; the dashed-line histogram is the scramble control; and the solid black-line histogram is miR-138. The percent change refers to the frequency of the positive cell population. Representative histograms are shown as above, and summary data dot plots are shown below the T-cell histograms, in which each dot represents the analysis of one human donor's peripheral CD4+ T cells (n = 5). *P < .05.

Because the mechanism of activity of ipilimumab has been shown to entail the activation of the T-cell ICOS/ICOS-ligand pathway30–32 and the ICOS ligand is expressed by glioma cells,33 we evaluated whether miR-138 would alter ICOS expression in human T cells but found that there was no difference after miR-138 transfection relative to scramble control stimulated and unstimulated CD4+ cells (data not shown), indicating that ICOS expression is probably not a suitable biomarker for miR-138 activity.

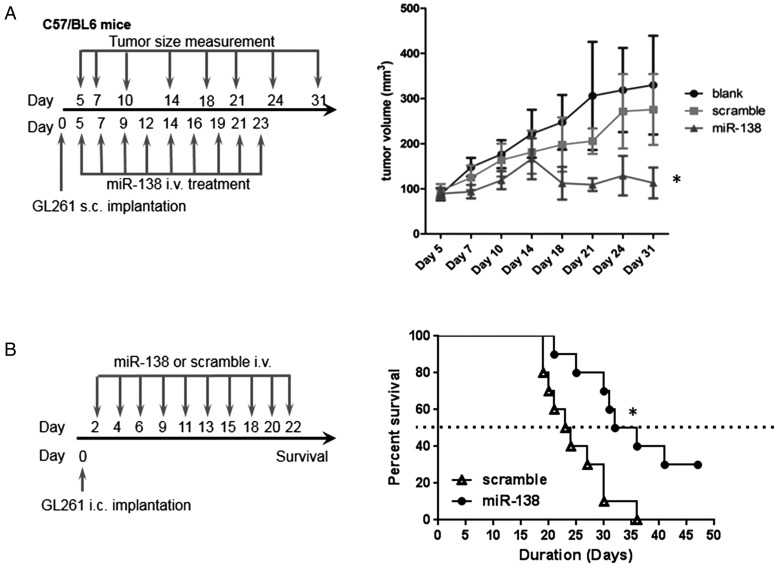

MiR-138 Inhibits In vivo Glioma Growth

Given the role of miR-138 in modulating the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways, we next determined whether miR-138 exerted a therapeutic effect in vivo. GL261 murine glioma cells were implanted into immune-competent C57BL/6J mice that were treated with miR-138 or scramble control (n = 5/group). After the subcutaneous GL261 tumors were palpable, either miR-138 duplex or scramble control was administered intravenously. Gliomas started to shrink as soon as miR-138 was administered; moreover, the tumors continued to regress even after miR-138 treatment was discontinued. In contrast, tumors kept growing aggressively in scramble miRNA-treated and -untreated tumor-bearing groups of mice (P = .022 on day 31, t-test) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

MiR-138 suppresses GL261 tumors in a syngeneic mouse model. (A) The treatment schema and the volumes of subcutaneous GL261 tumors in C57BL/6J mice treated intravenously with either miR-138 or scramble control, or left untreated, starting on day 5 (n = 10/group/experiment). The figure is the result of a single experiment but was repeated with identical results. In the miR-138 group, *P < .01 compared with both the untreated and scramble control tumors. Standard deviations are shown. Arrows indicate days of treatment and tumor size measurements. (B) Treatment schema and graph of the Kaplan–Meier estimate demonstrating survival of C57BL/6J mice with intracranial GL261 tumors that were treated intravenously with miR-138 versus scramble control. MiR-138 treatment results in a marked increase in median survival time relative to that in the scramble control group (33.5 d and 23.5 d, respectively; P = .01). This experiment was repeated with similar results.

To ascertain whether systemic intravenous administration of miR-138 had a therapeutic effect on intracerebral gliomas, C57BL/6J mice with established GL261 tumors were treated with miR-138. In mice treated with miR-138, the median survival time was 33.5 days, which compared favorably with mice treated with the scramble control, with a median survival time of 23.5 days (P = .011, t-test) (Fig. 3B). In the aggressive B16 murine model of intracranial melanoma, treatment with miR-138 significantly increased median survival time by 23% (data not shown). Furthermore, there was no evidence of demyelination, macrophage infiltration, or lymphocytic infiltration in the non-tumor-bearing areas of the CNS that would indicate the induction of autoimmunity (data not shown).

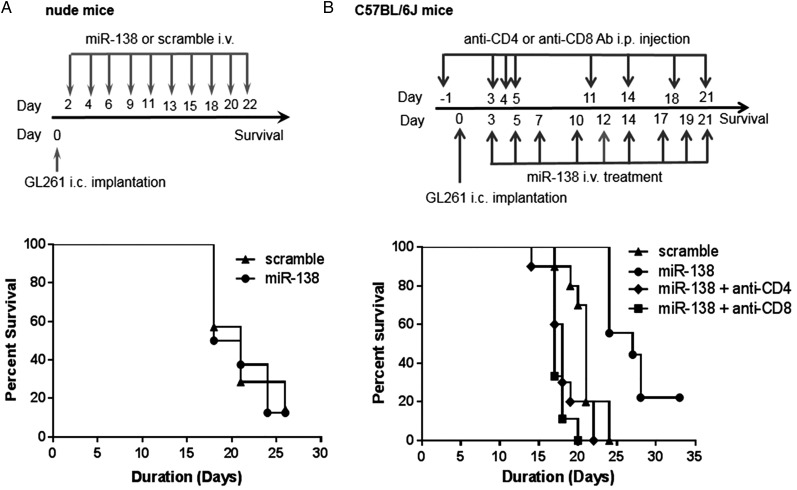

Therapeutic Effect of MiR-138 Is Immune Mediated

To determine whether the therapeutic effect of miR-138 is immunologically mediated, immune-deficient nude mice were implanted with GL261 cells and subsequently treated with miR-138. In the immune-incompetent animal background, miR-138 failed to exert any therapeutic effect, indicating that miR-138 mediates in vivo activity via the immune system (Fig. 4A). This was further supported by in vivo depletions of either the CD4 or CD8 T-cell population in immune-competent C57BL/6J mice with intracerebral GL261 tumors. Median survival was 17 or 18 days for mice depleted of either the CD4 or CD8 T-cell populations, respectively, similar to the scramble control group, which had a median survival of 21 days (Fig. 4B). Mice treated with miR-138 had a median survival of 27 days, which was statistically different compared with the CD4 (P < .0001, t-test) or CD8 (P < .0001, t-test) T-cell depletion groups.

Fig. 4.

The therapeutic effect of miR-138 is immune mediated. (A) Treatment schema and graph of the Kaplan–Meier survival estimate demonstrating the lack of therapeutic effect of miR-138 in nude mice with intracerebral (i.c.) GL261 gliomas (n = 8 in scramble control group, n = 7 in miR-138 treatment group, P = .87). (B) Treatment schema and graph of the Kaplan–Meier survival estimate demonstrating that the therapeutic efficacy of miR-138 is ablated in the setting of CD4 or CD8 T-cell depletions in C57BL/6J mice with i.c. GL261. MiR-138 treatment (n = 9) resulted in a median survival of 27 days in comparison with the scramble control (n = 10), which had a median survival of 21 days (P = .0001). When either CD4 (n = 9) or CD8 (n = 10) T cells were depleted, the median survival was 17 or 18 days, respectively. Ab, antibody.

To further validate that the therapeutic activity of miR-138 is related to immune modulation, we tested the direct antitumor effects of miR-138 at physiological levels that could be obtained in serum.27 No significant changes were observed for GL261 cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycling. The same amount of miR-138 could downregulate CTLA-4 and PD-1 expression on activated murine CD3+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. S3).

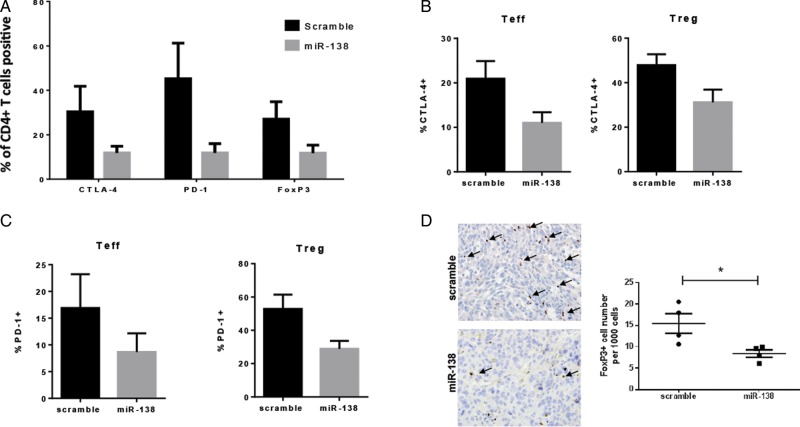

MiR-138 Modulates CTLA-4 and PD-1 In vivo

Intravenous administration of miR-138 in GL261 subcutaneously implanted mice demonstrated significant downregulation of CTLA-4, PD-1, and FoxP3 on CD4+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment (P < .05, two-sample t-test) (Fig. 5A). To clarify whether the CTLA-4 and PD-1 downregulation was specific to T effectors (CD4+FoxP3−) or Tregs (CD4+FoxP3+), these populations were gated and subsequently analyzed for CTLA-4 and PD-1 expression. We found that miR-138 downregulates these immune checkpoints in both populations (P < .05, unpaired t-test) (Fig. 5B for CTLA-4 and Fig. 5C for PD-1). Similarly, the reduction of CTLA-4 and PD-1 was observed on glioma-infiltrating CD4+ T cells in mice treated intracranially with miR-138 and implanted with GL261 (Supplementary Fig. S4); furthermore, ex vivo analysis of the miR-138-treated GL261 gliomas from the immune-competent mice demonstrated a reduction of FoxP3+ T cells by 51% relative to the scramble control (P = .000031, ANOVA test) (Fig. 5D). These data cumulatively suggest that, in vivo, miR-138 preferentially modulates the immune system, specifically, interacting with PD-1 and CTLA-4 to inhibit tumor-infiltrating Tregs and subsequently relieve the brake by these immunosuppressive cells within the tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 5.

MiR-138 downregulates immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment. (A) Ex vivo analysis of the expression of PD-1 and CTLA-4 on CD4+ cells from the tumor microenvironment of miR-138- and scramble-control-treated C57BL/6J mice implanted with subcutaneous GL261 tumors, as measured by flow cytometry. (B) Bar graphs showing downregulation of CTLA-4 expression on glioma-infiltrating effector T cells (Teff, CD4+FoxP3−) and glioma-infiltrating regulatory T cells (Treg, CD4+FoxP3+) in C57BL/6J mice harboring subcutaneous GL261 treated with miR-138 (n = 5/group). (C) Bar graphs showing PD-1 expression on the same cells as panel (B). (D) Photomicrograph (400×) showing FoxP3-expressing lymphocytes in GL261 tumors treated with scramble control and in those treated with miR-138. The dot plot graph summarizes the number of FoxP3+ cells per 1000 observed in scramble- and miR-138-treated intracerebral GL261 tumors. *P < .05.

Discussion

MiRNA-based immunotherapeutics are emerging as a new approach in the treatment of malignancies. Our miRNA screening of multiple miRNA-targeting algorithms suggested potential interactions of miR-138 with PD-1 and CTLA-4. These targets were validated using luciferase expression assays, functional immune assays, and ex vivo analysis of murine gliomas treated with miR-138. In immune-competent C57BL/6J mice with implanted subcutaneous GL261 tumors, significant regression of tumors occurred after treatment with miR-138, whereas further progression was noted in mice treated with scramble control. Systemic administration of miR-138 exerted a therapeutic effect against gliomas that is immunologically mediated, as reflected by the loss of therapeutic activity in immune-incompetent backgrounds. Furthermore, miR-138 decreased CTLA-4 and PD-1 expression both in ex vivo human T-cell assays and during the therapeutic window of murine models of glioma.

While miR-138 has been found to be a tumor suppressor by other investigators, this is the first report demonstrating therapeutic activity by administration of the drug into the bloodstream rather than by stable transfection in vitro.26,34–38 These previous studies used stable transfection of the miRNA of interest into cell lines ex vivo with subsequent implantation into mice brains as proof of principal of targeted effects. This is not a clinically applicable approach, and we have previously shown that miRNAs coadministered systemically with Lipofectamine are delivered to the T-cell compartment (3-fold increase) without appreciable quantities penetrating the tumor.27 Furthermore, there is no evidence that stable transfection of the glioma cells can be achieved even with direct infusion of the microRNA into a tumor with convection enhanced delivery. As such, we devised the current strategy of manipulating the immune population to mediate the direct tumor cytotoxic effects. Our in vitro experiments show that treatment of GL261 glioma cells with in vivo physiological doses of miR-138 does not exert any direct antitumor effect, which is further substantiated by the lack of efficacy of miR-138 treatment in immune-incompetent mice and during in vivo T-cell depletions. Cumulatively, these findings support our hypothesis that miR-138 exerts its anti-glioma efficacy by regulating the immune system rather than by a direct effect on the tumor itself.

Ipilimumab, by blocking CTLA-4 function, was the first immunomodulatory mAb to be FDA approved, after demonstrating a survival benefit in metastatic melanoma patients.11 A second blocking mAb that targets PD-1 (nivolumab, BMS-936558, MDX-1106) has shown clinical activity in heavily pretreated patients with advanced melanoma,17 and coadministration of these mAbs in melanoma patients demonstrated an objective response rate of 47%, showing potent synergy.39 Given this, it is not surprising that miR-138, by targeting both PD-1 and CTLA-4, demonstrated efficacy in murine models of malignancy. The GL261 murine model was selected for our analysis because it is known to express PD-L1. Ultimately these effects may be less robust in human gliomas, where there is greater heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression.40 Furthermore, we observed only partial downregulation of PD-1 and CTLA-4 expression by miR-138, which could be due to insufficient delivery of the miRNA with our current technique or the participation of other undefined epigenetic regulators. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that miR-138 exerts immune modulatory effects on other immune populations contributing to the therapeutic efficacy.

In comparison with other types of tumors, targeted therapy has not had a major impact on the treatment of glioblastoma, probably secondary to the marked heterogeneity, plasticity, and redundancy of signaling pathways in this malignancy. Current consensus is that successful new therapeutic approaches to glioblastoma must include combinational approaches targeting several molecular pathways.41 This provides a rationale for the development of agents such as miR-138 that target multiple mechanisms of tumor-mediated immune suppression, which is further supported by the knowledge that despite effective CTLA-4 blockade, PD-1 becomes upregulated as a compensatory mechanism.42 Furthermore, due to the nucleic acid sequence homology of miR-138 among almost all species, translational studies can be rapidly conducted without the necessity for developmental delays and costs, such as humanization of mAbs. Finally, because miR-138 can be synthesized by any investigator, as opposed to having to obtain a proprietary antibody, the scientific community has global access to this agent.

Given that our treatment strategy requires delivery of the miRNAs to the circulating immune system rather than directly to the tumor microenvironment, blood–brain barrier issues that limit delivery have been reduced. There was no significant toxicity or evidence of induced autoimmunity, similar to our prior miRNA immune modulators miR-12427 and miR-142-3p.43 We are currently optimizing lipid nanoparticle delivery to the PBMC compartment44 and will then evaluate therapeutic efficacy of the lead formulation in comparison with immune checkpoint antibodies. The relative ease of miRNA synthesis and nanoparticle formulation may avoid the challenges of scale encountered with cell-based immune therapeutics. Furthermore, easy production lowers costs, and miRNA biocompatibility may demonstrate a favorable toxicity profile.

Optimal antitumor immune responses require an antigenic target, immune activation, trafficking to the tumor microenvironment, and maintenance of effector function. It is plausible that immune-checkpoint targeting therapies are most likely to benefit those patients in which there is a preexisting tumor immune response. Given the variable expression of immune suppressive mechanisms and pathways throughout the different subtypes of glioblastoma,20 there may be an opportunity to combine these various miRNAs for further therapeutic synergy and more comprehensive targeting of tumor-mediated immune suppression. Ultimately the full potential of immune therapeutics will be realized when these approaches are combined with tumor targets and immune activators and within the context of standard of care such as radiation and chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the Dr. Marnie Rose Foundation and the National Institutes of Health #CA1208113, P50 CA093459, P50 CA127001, and P30 CA016672 to A.B.H., and Career Development grant #P50 CA127001 to J.W.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Flow Cytometry and Cellular Imaging Core Facility at MDACC funded by the National Cancer Institute #CA16672 for their assistance with flow cytometry data acquisition, and David Wildrick, Lamonne Crutcher, and Audria Patrick for their editorial and administrative support.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(5):492–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6029–6033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciafre SA, Galardi S, Mangiola A et al. Extensive modulation of a set of microRNAs in primary glioblastoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334(4):1351–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heimberger AB, Abou-Ghazal M, Reina-Ortiz C et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in human gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(16):5166–5172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fecci PE, Mitchell DA, Whitesides JF et al. Increased regulatory T-cell fraction amidst a diminished CD4 compartment explains cellular immune defects in patients with malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66(6):3294–3302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Andaloussi A, Lesniak MS. An increase in CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes of human glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol. 2006;8(3):234–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas AA, Ernstoff MS, Fadul CE. Immunotherapy for the treatment of glioblastoma. Cancer J. 2012;18(1):59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fecci PE, Ochiai H, Mitchell DA et al. Systemic CTLA-4 blockade ameliorates glioma-induced changes to the CD4+ T cell compartment without affecting regulatory T-cell function. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(7):2158–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Intlekofer AM, Thompson CB. At the bench: preclinical rationale for CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade as cancer immunotherapy. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94(1):25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirano F, Kaneko K, Tamura H et al. Blockade of B7-H1 and PD-1 by monoclonal antibodies potentiates cancer therapeutic immunity. Cancer Res. 2005;65(3):1089–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsa AT, Waldron JS, Panner A et al. Loss of tumor suppressor PTEN function increases B7-H1 expression and immunoresistance in glioma. Nat Med. 2007;13(1):84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloch O, Crane CA, Kaur R et al. Gliomas promote immunosuppression through induction of B7-H1 expression in tumor-associated macrophages. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(12):3165–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Carlsson R, Ambjorn M et al. PD-L1 expression by neurons nearby tumors indicates better prognosis in glioblastoma patients. J Neurosci. 2013;33(35):14231–14245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3167–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolchok JD, Kluger HM, Callahan MK et al. Safety and clinical activity of nivolumab (anti-PD-1, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in combination with ipilimumab in patients (pts) with advanced melanoma (MEL). Paper presented at: 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doucette TA, Rao G, Rao A et al. Immune heterogeneity of glioblastoma subtypes: extrapolation from The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(2):112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin Y, Chen D, Cabay RJ et al. Role of microRNA-138 as a potential tumor suppressor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013;303:357–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegel G, Obernosterer G, Fiore R et al. A functional screen implicates microRNA-138-dependent regulation of the depalmitoylation enzyme APT1 in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(6):705–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Jiang L, Wang A et al. MicroRNA-138 suppresses invasion and promotes apoptosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2009;286(2):217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitomo S, Maesawa C, Ogasawara S et al. Downregulation of miR-138 is associated with overexpression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase protein in human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(2):280–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamasaki T, Seki N, Yamada Y et al. Tumor suppressive microRNA138 contributes to cell migration and invasion through its targeting of vimentin in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(3):805–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh YM, Chuang CM, Chao KC et al. MicroRNA-138 suppresses ovarian cancer cell invasion and metastasis by targeting SOX4 and HIF-1alpha. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(4):867–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei J, Wang F, Kong LY et al. MiR-124 inhibits STAT3 signaling to enhance T cell-mediated immune clearance of glioma. Cancer Res. 2013;73(13):3913–3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sielska M, Przanowski P, Wylot B et al. Distinct roles of CSF family cytokines in macrophage infiltration and activation in glioma progression and injury response. J Pathol. 2013;230(3):310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heimberger AB, Crotty LE, Archer GE et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor VIII peptide vaccination is efficacious against established intracerebral tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4247–4254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu T, He Q, Sharma P. The ICOS/ICOSL pathway is required for optimal antitumor responses mediated by anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cancer Res. 2011;71(16):5445–5454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carthon BC, Wolchok JD, Yuan J et al. Preoperative CTLA-4 blockade: tolerability and immune monitoring in the setting of a presurgical clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(10):2861–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen H, Liakou CI, Kamat A et al. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy results in higher CD4+ICOShi T cell frequency and IFN-gamma levels in both nonmalignant and malignant prostate tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(8):2729–2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schreiner B, Wischhusen J, Mitsdoerffer M et al. Expression of the B7-related molecule ICOSL by human glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. Glia. 2003;44(3):296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang H, Tang Y, Guo W et al. Up-regulation of microRNA-138 induce radiosensitization in lung cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2014;357:6557–6565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao Y, Fan X, Li W et al. miR-138–5p reverses gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells via negatively regulating G protein-coupled receptor 124. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446(1):179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Islam M, Datta J, Lang JC et al. Down regulation of RhoC by microRNA-138 results in de-activation of FAK, Src and Erk1/2 signaling pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(5):448–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakrabarti M, Banik NL, Ray SK. MiR-138 overexpression is more powerful than hTERT knockdown to potentiate apigenin for apoptosis in neuroblastoma in vitro and in vivo. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319(10):1575–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee YC, Tzeng WF, Chiou TJ et al. MicroRNA-138 suppresses neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin expression and inhibits tumorigenicity. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e52979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):122–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nduom EK, Wei J, Yaghi NK et al. PD-L1 expression and prognostic impact in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2016;182:195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen PY, Lee EQ, Reardon DA et al. Current clinical development of PI3K pathway inhibitors in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(7):819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curran MA, Montalvo W, Yagita H et al. PD-1 and CTLA-4 combination blockade expands infiltrating T cells and reduces regulatory T and myeloid cells within B16 melanoma tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(9):4275–4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu S, Wei J, Wang F et al. Effect of miR-142–3p on the M2 macrophage and therapeutic efficacy against murine glioblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(8):pii: dju162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yahghi NK, Wei J, Kong LY et al. An optimized therapeutic nanoparticle delivery platform of miRNA in preclinical murine models of malignancy. Paper presented at: AACR American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2015; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.