Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To systematically review the current literature on mortality and functional outcomes after emergency major abdominal surgery in older adults.

DESIGN

Systematic literature search and standardized data collection of primary research publications from January 1994 through December 2013 on mortality or functional outcome in adults aged 65 and older after emergency major abdominal surgery using PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane, and CINAHL. Bibliographies of relevant reports were also hand-searched to identify all potentially eligible studies.

SETTING

Systematic review of retrospective and cohort studies using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses, Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology, and A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews guidelines.

PARTICIPANTS

Older adults.

MEASUREMENTS

Articles were assessed using a standardized quality scoring system based on study design, measurement of exposures, measurement of outcomes, and control for confounding.

RESULTS

Of 1,459 articles screened, 93 underwent full-text review, and 20 were systematically reviewed. In-hospital and 30-day mortality of all older adults exceeded 15% in 14 of 16 studies, where reported. Older adults undergoing emergency major abdominal surgery consistently had higher mortality across study settings and procedure types than younger individuals undergoing emergency procedures and older adults undergoing elective procedures. In studies that stratified older adults, odds of death increased with age. None of these studies examined postoperative functional status, which precluded including functional outcomes in this review. Differences in exposures, outcomes, and data presented in the studies did not allow for quantification of association using metaanalysis.

CONCLUSION

Age independently predicts mortality after emergency major abdominal surgery. Data on changes in functional status of older adults who undergo these procedures are lacking.

Keywords: emergency surgery, mortality, functional status, postoperative complications

Because the proportion of emergency, rather than elective, procedures increases with age,1,2 demographic shifts will increase the demand for emergency major abdominal procedures among older adults in the coming decades.3,4 Moreover, almost 20% of older adults undergo an inpatient surgical procedure in the last month of life, and many in the last week of life, indicating the important role of surgery in end-of-life care. Nevertheless, significant variation according to age and geographic region suggests substantial complexity and provider discretion regarding decisions for surgical interventions in older aduts.5 Decisions for emergency surgery in older adults can be particularly challenging for a number of reasons. First, people in critical condition are often unable to participate in preoperative conversations and must rely on surrogate decision-makers. Second, the surgical problem is usually unanticipated, and therefore people are unlikely to have indicated their treatment preferences for this specific clinical situation. Third, decisions are rushed by necessity, and the individuals are often unfamiliar to the surgical team. Finally, the lack of information on postoperative prognosis and functional outcomes in older adults further hampers informed decision-making. A better understanding of these outcomes would benefit patients, surrogates, and clinicians in setting appropriate expectations before surgery and optimizing perioperative management.

To address this knowledge gap, a systematic review of the English language literature was conducted to determine mortality and functional outcomes after emergency major abdominal surgery in older adults.

METHODS

The study design, search strategy, and study quality assessment rubric were designed based on recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement,6 Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines,7 the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement,8 and the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool.9 Before this search was initiated, the population of interest was defined as individuals aged 65 and older undergoing emergency major abdominal procedures. The primary outcome of interest was mortality after surgery. The secondary outcome was functional status after surgery.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

After devising a search strategy in consultation with a medical librarian, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Database, and CINAHL were searched between April 8 and April 15, 2014, for English-language original research published in peer-reviewed journals between January 1, 1994, and December 31, 2013. The search used subject descriptors and free-text words related to emergency abdominal surgery, surgical outcomes including functional status, and mortality in adults aged 65 and older. To avoid studies focused on nonabdominal surgery the search terms cardiac, thoracic, vascular, hip, orthopedic, breast, lung, extremities, head and neck, and trauma were excluded. The full search strategy for each of the five databases is included in Appendix S1. This search was supplemented by hand-searching the bibliographies of the final full-text articles to identify potentially relevant studies. End Note X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY) was used to organize references and full-text documents.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies that met the following five criteria were included in full-text review: included emergency procedures (operations after nonelective admissions or that the surgeon considered to be an emergency; primarily described any combination of abdominal procedures performed on the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, spleen, pancreas, or hepatobiliary tract; included individuals aged 65 and older; reported mortality or functional status after emergency procedures in older adults as a primary outcome; and compared mortality or functional outcomes in older adults undergoing emergency surgery to older adults undergoing elective surgery.

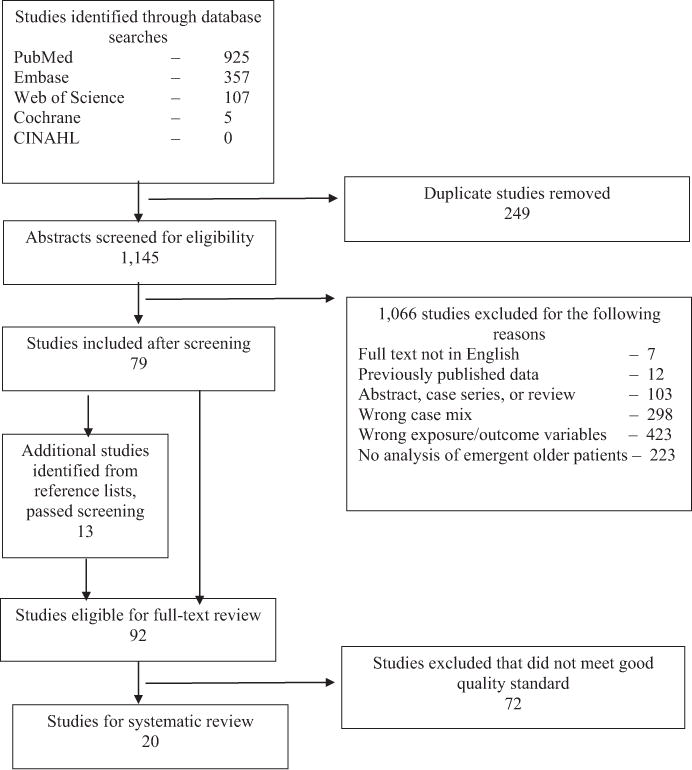

To improve comparability of findings, studies in which laparoscopic procedures, appendectomy, esophageal, or genitourinary procedures accounted for more than 25% of the study sample and studies that included any breast, lung, extremities, head and neck, or trauma procedures were excluded. Studies in which the full text was not in English; studies that presented previously analyzed published data; and editorials, abstracts, conference proceedings, case reports, case series (n < 50), and previous reviews were also excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study screening process. CINAHL =cumulative index for nursing and allied health literature

Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Data Synthesis

Two researchers (ZC, JWS) reviewed titles and abstracts resulting from the initial database searches to identify those eligible for full-text review. Articles that could not be clearly excluded were discussed between reviewers, and inclusion was determined through consensus. Articles selected for full-text review were subject to quality review (ZC, JWS) based on a quality assessment tool (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality-of-Evidence Rubric

| Category | Good | Fair | Poor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size of older adults undergoing emergency major abdominal surgery | >100 | 99−50 | <50 |

| Exposure and inclusion: age group | Control versus ≥2 older groups | Binary (older vs control)a | No specific older group |

| Outcomes | |||

| Mortality | ≥30 days | In-hospital | Undetermined |

| Functional status | Pre- and postoperative measures | Postoperative measures | None |

| Control for confounding | |||

| Control groups | Age and urgency control groups | Age or urgency control groups | Neither age nor urgency control groups |

| Statistical analysis | Multivariate analysis | Stratified results or univariate analysis | None |

Includes studies in which inclusion criteria restricted sample to older adults.

Quality Assessment Tool

Before the search was initiated, a quality assessment tool was designed to assess the data quality and risk of bias of each study (Table 1). Development of the quality assessment tool was based on established guidelines on reporting of results in observational studies and systematic reviews,6–9 but no prior quality assessment criteria for nonrandomized studies accounted for the degree of heterogeneity of eligible studies. Thus, in the absence of a widely accepted quality assessment scale,10 a previously developed approach11 was used to develop criteria for the studies that met the a priori eligibility criteria (Table 1). The following four main quality categories were considered (corresponding to six grading elements): sample size; exposure and inclusion criteria (elderly adults stratified according to age and a nonelderly control group); reporting of outcomes of interest (mortality and functional status); and method of controlling for confounding (control groups and type of statistical analysis). Studies were considered to have good evidence quality if they achieved scores of good in three categories and at least fair quality in the fourth. Poor-quality studies failed to achieve a score of fair in all categories. The remaining studies were classified as having overall fair evidence quality. Only studies considered of good quality are included in this review; excluded studies are listed in Appendix S2. Because of the wide heterogeneity in defining the elderly or aged population, ages of the comparison groups, range of operative procedures, inconsistent definitions of emergency status, and variations in outcome reporting (Table 2), a quantitative meta-analysis was not possible.12 Thus a descriptive synthesis of the outcomes of interest in eligible studies was performed.

Table 2.

Clinical Heterogeneity of Studies in Review

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Definition of “elderly” | |

| 60 | 1 (5) |

| 61 | 1 (5) |

| 65 | 6 (30) |

| 70 | 7 (35) |

| 80 | 5 (25) |

| Number of age groups defined as “elderly” | |

| 1 | 5 (25) |

| 2 | 9 (45) |

| 3 | 3 (15) |

| 4 | 2 (10) |

| 6 | 1 (5) |

| Procedure type | |

| Major abdominal procedurea | 5 (25) |

| Colon, malignant | 5 (25) |

| Colon, mixed benign and malignantb | 5 (25) |

| Colon, benign | 3 (15) |

| Perforated peptic ulcer | 1 (5) |

| Diagnosis of acute abdomen | 1 (5) |

| Included elective cases for comparison | 6 (30) |

| Method for defining “emergency” cases | |

| Standardized database definitions | 7 (35) |

| After nonelective admission | 5 (25) |

| Within 12, 24, or 72 hours of admission | 2 (10) |

| Defined by disease process | 2 (10) |

| Defined emergence by surgeon | 1 (5) |

| No specific definition provided | 3 (15) |

| Included younger individuals for comparison | 12 (60) |

| Age range of “younger” comparison participantsc | |

| 16–39 | 1 (8) |

| 16–64 | 1 (8) |

| 17–69 | 1 (8) |

| 18–50 | 1 (8) |

| 18–55 | 1 (8) |

| 18–69 | 1 (8) |

| 18–79 | 1 (8) |

| 20–64 | 1 (8) |

| 23–69 | 1 (8) |

| <70d | 1 (8) |

| <80d | 1 (8) |

| 65–79e | 1 (8) |

| Mortality measuref | |

| In-patient | 5 (25) |

| 30-day | 15 (75) |

| 1-year | 3 (15) |

| >1-year | 1 (1) |

Including exploratory laparotomy.

Proportion of malignant cases ranged from 18% to 54%.

n = 12.

Lower age bound not defined.

Older comparison group age >79.

Because each study may have had more than one mortality measure, these proportions add up to more than 100%.

Study Variables

From each study, the approach used to describe mortality and functional outcomes in older adults and the incidence or odds ratios for each outcome for the older age groups undergoing emergency surgery were abstracted. Outcomes of individuals younger than 65 undergoing emergency surgery were descriptively compared with those of older adults undergoing nonemergency procedures. Finally, whether each study identified individual, operative, or hospital factors associated with the outcomes of interest was determined.

For the final set of studies, the following specific characteristics of older adults undergoing emergency major abdominal surgery were described: setting; design (e.g., prospective, retrospective) and years of data collection; types of surgical procedures; how the age variable was defined (cutoff age, continuous or stratified); number of older adults undergoing emergency surgery included in the study; main outcome and duration of follow up (e.g., in-hospital, 30-day, 1-year); mortality; difference in mortality from younger individuals undergoing emergency surgery; difference in mortality from older adults undergoing nonemergency surgery; factors significantly associated with worse survival; postoperative functional outcomes; and other reported outcomes (complications, hospital length of stay).

RESULTS

Search Results

The initial search of five databases found 1,145 unique articles. After excluding studies from the database search and including studies identified using manual review of references, the 92 studies eligible for full-text review underwent quality ranking (Figure 1). After quality assessment, 20 articles met criteria for good overall study quality and were thus included in the final selection for review (Appendix S3).

Study Characteristics

Ten countries are represented in this selection, with the most articles representing individuals from the United States (n = 7)13–19 and the United Kingdom (n = 3).20–22 Data sources included individual acute care hospitals (n = 5),13,23–26 small groups of acute care hospitals (n = 2),27,28 a statewide cancer registry (n = 1),14 national cancer registries (n = 3),29–31 national hospital databases (n = 4),20,21,32 and the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database (n = 5).15–19 Regarding study design, two were prospective,29,32 one study used retrospective and prospective data,24 and the remaining studies were retrospective reviews.

Of the 20 studies, 14 included only individuals who underwent urgent or emergency surgery, whereas six included elective and urgent or emergency operations.14,23,25,29,31,32 Definitions of emergency procedures included standardized definitions from prospectively collected databases (n = 7);15–19,22,30 procedures occurring after nonelective hospital admissions (n = 5);13,14,20,21,24 procedures occurring in the first 12, 24, or 72 hours after an unplanned admission (n = 2);26,32 procedures for emergency pathology (n = 2);27,28 procedures defined as emergency by the surgeon (n = 1);31 and three studies that provided no specific definition for emergency procedures.23,25,29

The types of surgeries also differed between studies. Thirteen included only major colon surgeries,13,14,16,18–21,25–27,29–31 two included only laparotomies,15,22 one included surgeries only for perforated peptic ulcers,28 and the remaining five studies included some variation of major abdominal surgery on the upper digestive tract (n = 4),15,17,23,32 small bowel (n = 4),15,17,24,32 biliary tract (n = 4),17,23,24,32 pancreas (n = 2),15,32 abdominal wall hernias (n = 1),17 and large bowel (n = 5)15,17,23,32 and exploratory laparotomies (n = 5).15,17,22–24

Eight of the studies reviewed included only older adults, which was defined according to numerous age cutoffs, including 80 and older (n = 5),14,16,18,23,29 70 and older (n = 7),20–22,24,25,28,31 65 and older (n = 6),13,17,19,26,27,32 and 60 and older (n = 2).15,30 The sample size of the older adults undergoing emergency procedures ranged from 87 to 42,047.20,27

Functional Outcome

None of the studies included in this review reported on postoperative functional status; thus, the effect of emergency major abdominal operations on the functional status of older adults could not be assessed.

Mortality

Five studies13,14,24,25,29 reported in-hospital mortality, and 15 reported 30-day mortality as their primary outcome. Three studies also reported 1-year mortality,14,20,21 and one reported mortality through 31.5 months of followup.23

There was wide variation across studies in reported mortality in older adults. Table 3 shows the reported mortality in older adults undergoing emergency major abdominal surgery, younger individuals emergency surgery, and older adults undergoing nonemergency surgery. For example, for emergency colonic operations, in-hospital mortality ranged from 15% of individuals aged 65 and older at a single institution in the United States13 to 42% of individuals aged 90 and older at another in Spain.25 Reported 30-day mortality ranged from 6% of individuals aged 65 to 79 at one Spanish hospital26 to 48% of nonagenarians in a national colon cancer database in Denmark.30 Finally, 1-year mortality measured in individuals undergoing emergency colectomy in England ranged from 35% of those aged 70 to 75 to 51% of those aged 80 and older.21 Despite such variation, there were stable trends across studies. First, in each of eight studies that reported mortality after emergency major abdominal surgery, mortality increased with age.19,21,22,24–27,30 Second, older adults uniformly had higher odds of death after emergency surgery than individuals younger than 65.15,16,18–20,27,28,30,31

Table 3.

Mortality for Elderly Adults Undergoing Emergency Major Abdominal Surgery Compared with that of Younger Individuals Undergoing Emergency Major Abdominal Surgery and Elderly Adults Undergoing Elective Surgery

| Author, Year (Country) | Age Groupsa | Study Population | Mortality Measure | Mortality According to Age, % | Compared with Elderly Adults Undergoing Elective Surgery | Compared with Younger Individuals Undergoing Emergency Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arenal-Vera et al. (2011) (Spain) | 23–69 70–79 80–89 90–99 |

Colonic resection for colon cancer | Postoperative | 70–79: 21 80–89: 24 ≥90: 42 |

70–79: 6%b 80–89: 11%b ≥90: 12%b |

16%, NS |

| Arenal et al. (2003) (Spain) | 70–79 ≥80 |

Emergency surgery for acute abdomen | In-hospital | 70–79: 19 ≥80: 24 |

– | – |

| McGillicuddy et al. (2009) (United States) | 65–100 | Emergency colon resections | In-hospital | 15 | – | – |

| Marusch et al. (2005) (Germany) | <80 ≥80 |

Colonic resection for colon cancer | In-hospital | 22 | 6%, P < .001 | 8%, P < .001 |

| Kunitake et al. (2010) (United States) | >80 | Colonic resection for colon cancer | In-hospital and 1-year | Not reported | In-hospital: OR 1.52, 95% CI = 1.33–1.73 1-year: OR 1.39, 95% CI = 1.27–1.53 |

– |

| Abbas et al. (2003) (New Zealand) | 80–84 85–97 |

Elective or emergency major abdominal surgery | 30-day | 29 | 8%, P < .001 | – |

| Iversen et al. (2008) (Denmark) | 18–50 51–60 61–70 71–80 81–90 91–100 |

Emergency colon resection for cancer | 30-day | 61–70: 11 71–80: 24 81–90: 35 ≥91: 48 |

– | Ref: <50 61–70: OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 0.5–3.4 71–80: OR = 2.9, 95% CI = 1.2–7.4 81–90: OR = 4.7, 95% CI = 1.9–12.1 ≥91: OR = 10.3, 95% CI = 3.6 –29. |

| Pepin et al. (2009) (Canada) | 20–64 65–74 75–88 |

Emergency colectomy for Clostridium difficile infection | 30-day | 65–74: 39 ≥75: 46 |

– | Ref: 18–64 65–74: OR = 2.08, 95% CI = 0.76–5.73 ≥75: OR = 2.86, 95% CI = 1.18–6.90 |

| Duron et al. (2011) (France) | 16–64 ≥65 |

Major digestive surgery | 30-day | 34 | OR 3.42, 95% CI = 1.67–6.99 | 7% P ≤ .001 |

| Hemmer et al. (2011) (the Netherlands) | 17–69 70–96 |

Emergency surgery for perforated ulcer | 30-day | ≥70: 37 | – | Ref: 17–69 ≥70: OR = 3.5 (P < .002)b |

| Kwok et al. (2011) (United States) | 80–99 ≥90 |

Emergency colectomy | 30-day | ≥80: 29 | – | Ref: 80–89 ≥90 years: 1.6 (P < .05)b |

| Al-Temimi et al. (2012) (United States) | 16–39 40–49 50–59 60–69 70–79 80–89 90 |

Emergency laparotomy | 30-day | Not reported | – | Ref: 16–39 60–69: OR = 2.25, 95% CI = 1.76–2.89 70–79: OR = 3.25, 95% CI = 2.54–4.17 80–89: OR = 5.48, 95% CI = 4.25–7.07 ≥90: OR = 7.73, 95% CI = 5.70–10.47 |

| Kolfschoten et al. (2012) (the Netherlands) | <70 70–79 ≥80 |

Colonic resection for colon cancer | 30-day | Not reported | Not reported | Ref: <70 70–79: OR = 1.90, 95% CI = 1.09–3.29 ≥80: OR = 3.10, 95% CI = 1.80–5.34 |

| Lidsky et al. (2012) (United States) | 18–65 65–79 ≥80 |

Emergency surgery for acute colonic diverticulitis | 30-day | 65–79: 10 ≥80: 18 |

– | Ref: 65–79 ≥80: OR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.5–4.8 |

| Modini et al. (2012) (Italy) | 65–79 80–97 |

Emergency colonic resection | 30-day | 65–79: 6 ≥80: 30 |

– | – |

| Saunders et al. (2012) (England) | 18–69 70–79 80–89 90–99 |

Emergency laparotomy | 30-day | 70–79: 20 80–89: 24 ≥90: 31 |

– | 10%b |

| Scarborough et al. (2012) (United States) | 65–69 70–74 75–79 80–84 85–89 ≥90 |

Emergency abdominal operation | 30-day | Overall: 30 DNR: 37 No DNR: 22 |

– | – |

| Ballian et al. (2013) (United States) | 18–79 ≥80 |

Emergency surgery for acute colonic diverticulitis | 30-day | ≥80: 18 | – | Ref: 18–79 ≥80: OR = 5.3, 95% CI = 1.9–14.8 |

| Mamidanna et al. (2012) (England) | 70–75 76–80 ≥81 |

Emergency colectomy | 30-day and 1-year | 30-day: 70–75: 17 76–80: 23 ≥81: 31 1-year: 70–75: 35 76–80: 42 ≥81: 51 |

– | – |

| Faiz et al. (2010) (England) | 18–55 55–69 70–79 ≥80 |

Emergency colectomy | 30-day and 1-year | Not reported | – | 30-day, Ref: 18–55 70–79: OR = 6.25, 95% CI = 5.73–6.82 ≥80: OR = 12.31, 95% CI = 11.27–13.45 1-year, Ref: 18–55 70–79: OR = 4.81, 95% CI = 4.43–5.23 ≥80: OR = 9.23, 95% CI = 8.46–10.07 |

NS = not significant; CI = confidence interval; Ref = reference group used to calculate odds ratios (ORs); DNR = do not resuscitate.

When reported by study authors, upper and lower age bounds of the study sample are provided.

No statistical test provided by authors.

Both studies that compared mortality in older adults undergoing elective surgery with older adults undergoing emergency surgery found that emergency status independently predicted mortality.14,32 A retrospective study of individuals in a statewide registry undergoing resections for colon cancer found that the odds of in-hospital (odds ratio (OR) = 1.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.33–1.73) and 1-year (OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.27–1.53) mortality were higher for emergency patients.14 Similarly, another study found that odds of death were more than three times as high after emergency major digestive tract surgery (OR = 3.4, 95% CI = 1.67–6.99).32 Three additional studies did not report ORs for association between emergency surgery and mortality, but instead presented mortality rates of the emergency and elective cohorts.25,29,31 In all cases, the elective cohort had lower mortality (6%, 8%, and 6%) than their emergency counterparts (29%, 22%, and 21%, respectively).

Studies also differed in which individual characteristics, operative details, and postoperative complications were analyzed, although the following factors were significantly associated with worse survival in older adults undergoing emergency surgery in multiple studies: renal dysfunction (variably defined as acute kidney injury16,19,21 or chronic renal insufficiency requiring dialysis13,16,19,21), higher American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) Physical Status Classification System,21,23,31 presence of malignancy,16,21 preoperative shock,16,19 longer time from onset of symptoms to surgery,13,24 and use of preoperative corticosteroids.16,19 Three studies reported that certain surgical indications or types of surgery were associated with greater odds of death. A single-center study of older adults undergoing emergency surgery for an acute abdomen24 reported that mesenteric infarction, nontherapeutic laparotomy, and intestinal bypass with defunctionalized stoma were associated with greater mortality, whereas two retrospective reviews of national databases21,31 found that individuals undergoing subtotal colectomy had greater odds of death than those undergoing other types of colon resections.

Other Outcomes

In all studies reporting postoperative complications in older adults undergoing emergency procedures,13,17, 19–21,24,26,29,31 older adults had higher complication rates than younger individuals. For example, one study24 reported complications in 37% of individuals aged 80 and older, versus 25% of individuals aged 70 to 79; another study29 reported complications in 50% of individuals aged 80 and older, versus 34% in individuals younger than 80; and a third study20 reported greater odds of postoperative complications in individuals aged 80 and older than in those younger than 55 (OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.3–1.3). Also, older adults undergoing emergency procedures had higher complication rates than older adults undergoing elective procedures, with complications reported in 50% of individuals undergoing emergency surgery, versus 32% of those undergoing an elective procedure29 and in 33% of individuals undergoing emergency surgery, versus 20% of those undergoing an elective procedure.31 When reported, the most-common complications were pneumonia (10–25%),13,19 cardiac complications (2–20%),13,19,21,24 wound infection (6–16%),19,24 postoperative sepsis (6–13%),19,24 and respiratory insufficiency (unplanned reintubation, prolonged mechanical ventilation,19 nonspecified respiratory insufficiency) (8–19%).13,24

Hospital length of stay (LOS) was reported in seven studies.13,16,17,19–21,24 The reported median LOS of older adults ranged from 8 to 16 days,17,21,24 and the reported mean LOS was 12.6 to 26.9 days.13,16,19

Although none of the studies reviewed measured changes in functional status as a postoperative outcome, six of the 20 studies provided some measure of preoperative functional status.13,15–19 Reported proportions of older adults undergoing emergency surgery with nonindependent preoperative functional status ranged from 6.3% to 32.8%.15,19 In three of these studies, dependent preoperative functional status was not significantly associated with postoperative outcome,13,17,19 whereas in three others with much larger sample sizes, preoperative functional status was associated with greater than twice the odds of postoperative mortality.15,16,18 One study found that the magnitude of the relationship between dependent functional status and higher probability of death increased with age.15 Quality of life is another important outcome for older adults after major surgery, but it was not reported in any of the studies reviewed.

DISCUSSION

This review revealed considerable variability in studies about emergency major abdominal procedures in older adults, because of differences in how “older” is defined, which procedures are included, and how outcomes are measured. This systematic review of 20 studies synthesized these data to reveal high mortality in older adults of all ages across a variety of settings and a range of major abdominal procedures. Although the majority of older adults survived emergency surgery, the risk of in-hospital and 30-day mortality in individuals aged 80 and older is nearly 25% and approaches 50% in nonagenarians. It was also found that older adults uniformly had greater odds of death after emergency surgery than younger individuals,15,16,18–20,27,28,30,31 that mortality after emergency major abdominal surgery increased with older age in individuals aged 65 and older,19,21,22,24–27,30 and that emergency surgery was an independent risk factor for higher postoperative mortality in older adults. Understanding the magnitude of the excess mortality associated with emergency operations in older adults can help set expectations before surgery and guide perioperative decisions of older adults, families, and clinicians.

The nature of acute surgical conditions usually makes it prohibitive to optimize individuals before an emergency operation. Not surprisingly, comorbidities such as renal failure, physiological distress such as sepsis or shock, high ASA class, and immunosuppression were frequently associated with significantly greater mortality in older adults undergoing emergency surgery. Considering that emergency status alone predicts greater odds of death in older adults,32 these findings may suggest that deferring elective surgery in older adults with subacute surgical conditions that may ultimately present emergently (e.g., a hernia causing a small bowel obstruction or cholelithiasis that causes acute cholecystitis) may not ultimately benefit the individual. Rather, superior outcomes may be achieved in an elective setting, where preoperative physiology can be optimized or individuals can be prehabilitated. Even in the hospital setting, surgeons who are inclined to defer offering surgery as an option for high-risk older adults until they demonstrate clear signs of physiological deterioration may also reconsider that approach based on this body of evidence.

This review also identifies potentially modifiable risk factors that could be targeted to reduce mortality in this group. For example, pulmonary complications were the most frequent complications in older adults undergoing emergency surgery. Poor dentition, hospital-acquired delirium, and dysphagia commonly seen in older hospitalized individuals are associated with aspiration, which can lead to pneumonia and respiratory insufficiency.33,34 Efforts to develop clinical pathways to target these conditions have been successful in other individuals undergoing surgery and should implemented in this group as well.35,36 Increasing collaboration between geriatricians and surgeons, through comanagement or triggered consultation, has successfully reduced rates of postoperative complications and hospital LOS and improved long-term functional status in other surgical populations.37–39 Older adults undergoing emergency major abdominal surgery are another potential target for such interventions. Regardless of involvement by geriatricians, surgeons must become expert in caring for older adults, who now account for a growing proportion of individuals undergoing surgery.

It was surprising to find such a paucity of data on postoperative functional outcomes in older adults undergoing emergency surgery. Older adults experiencing a trauma can be expected to lose the ability to perform one activity of daily living in the first year after injury,40 and it would be extremely beneficial to understand whether older adults with other acute surgical emergencies fare similarly. Declines in functional status are associated with greater mortality and rates of institutionalization and hospital admission and poorer quality of life. Studies have shown that more than half of older adults who undergo emergency surgery were discharged to post-acute care facilities,2,13 highlighting the particular relevance of postoperative function and recovery in this population.

This study has a number of limitations. First, studies published over the past 20 years, a time during which there have been advances in surgical and intensive care that could have reduced mortality, were included, although results were fairly consistent over time. Second, excluding unpublished studies and reports may have omitted data reflecting even higher mortality, although this is unlikely to have had a major effect on the findings because unpublished studies are often of lower methodological quality and have smaller sample sizes, so they may not have met the quality criteria for final inclusion.41 Third, participants in these studies underwent a variety of procedures for a variety of surgical indications, and thus, findings from this review cannot necessarily be used to inform outcomes after a specific procedure. Despite such clinical heterogeneity, the major findings were consistent across studies and are relevant to perioperative decision-making for older adults undergoing emergency major abdominal procedures. A paucity of studies reporting long-term mortality or functional outcome limits this review. Only three of the 20 eligible studies examined mortality beyond 30 days. All three were restricted to individuals undergoing colectomy, and two used the same national database.19,20 Further research is needed to fill these major gaps in the literature about older adults undergoing surgery.

Despite the limitations of the current literature, this review can be useful for clinicians, individuals, and families making the difficult decision to undergo an emergency major abdominal operation. The data are consistent across studies in showing that these procedures are highly morbid and portend a high risk of in-hospital and 30-day death in older adults. In all cases, but especially in individuals with serious illness and poor physiological reserve, having conversations to identify the goals of treatment, to clarify expectations for recovery, and to assess the individual’s tolerance for the burdens of surgery are important first steps in delivering the best surgical care to older adults in need of emergency major abdominal procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Julia S. Whelan, medical librarian at Harvard Medical School’s Countway Library, for her guidance and assistance with search strategy design, refinement, and execution. The authors would also like to the Brigham & Women’s Hospital Medical Library for their assistance with procurement of full-text articles. Dr. Cooper is supported by a Jahnigen Career Development Award from the American Geriatrics Society and the National Institute of Aging GEMSSTAR 1R03AG042361-01. Dr. Mitchell is supported by a Mid-career Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research also from the National Institute of Aging K24AG033640.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All four authors have made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; to drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and to final approval of the version to be published.

Sponsor’s Role: There was no sponsor involvement in this study.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix S1 Database search strategies.

Appendix S2 Characteristics of poor and fair quality studies.

Appendix S3 Mortality among older patients undergoing emergent major abdominal surgery.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content, accuracy, errors, or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Barlow AP, Zarifa Z, Shillito RG, et al. Surgery in a geriatric population. Ann Royal Col Surg Engl. 1989;71:110–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blansfield JA, Clark SC, Hofmann MT, et al. Alimentary tract surgery in the nonagenarian: Elective vs. emergent operations J Gastro Surg. 2004;8:539–542. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. Progress Report on Alzheimer’s Disease. 1997 [on-line]. Available at http://www.nia.nih.-gov/sites/default/files/1997index.txt Accessed May 2, 2015.

- 4.Etzioni DA, Liu JH, Maggard MA, et al. The aging population and its impact on the surgery workforce. Ann Surg. 2003;238:170–177. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000081085.98792.3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, et al. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von EE, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Research Meth. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Europ J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: A systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:666–676. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Review of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. Section 9.1.4 When Not to Use Meta-Analysis in a Review [on-line] Available at http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_9/9_1_4_when_not_to_use_meta_analysis_in_a_review.htm Accessed May 2, 2015.

- 13.McGillicuddy EA, Schuster KM, Davis KA, et al. Factors predicting morbidity and mortality in emergency colorectal procedures in elderly patients. JAMA Surg. 2009;144:1157–1162. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunitake H, Zingmond DS, Ryoo J, et al. Caring for octogenarian and nonagenarian patients with colorectal cancer: What should our standards and expectations be? Dis Colon Rect. 2010;53:735–743. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181cdd658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Temimi MH, Griffee M, Enniss TM, et al. When is death inevitable after emergency laparotomy? Analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. J Am Col Surg. 2012;215:503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwok AC, Lipsitz SR, Bader AM, et al. Are targeted preoperative risk prediction tools more powerful? A test of models for emergency colon surgery in the very elderly. J Am Col Surg. 2011;213:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scarborough JE, Pappas TN, Bennett KM, et al. Failure-to-pursue rescue: Explaining excess mortality in elderly emergency general surgical patients with preexisting “do-not-resuscitate” orders. Ann Surg. 2012;256:453–461. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826578fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballian N, Rajamanickam V, Harms BA, et al. Predictors of mortality after emergent surgery for acute colonic diverticulitis: Analysis of National Surgical Quality Improvement Project data. J Trauma. 2013;74:611–616. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827d5d93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lidsky ME, Thacker JK, Lagoo-Deenadayalan SA, et al. Advanced age is an independent predictor for increased morbidity and mortality after emergent surgery for diverticulitis. Surgery. 2012;152:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faiz O, Warusavitarne J, Bottle A, et al. Nonelective excisional colorectal surgery in English National Health Service Trusts: A study of outcomes from Hospital Episode Statistics Data between 1996 and 2007. J Am Col Surg. 2010;210:390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mamidanna R, Eid-Arimoku L, Almoudaris AM, et al. Poor 1-year survival in elderly patients undergoing nonelective colorectal resection. Dis Colon Rect. 2012;55:788–796. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182585a35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders DI, Murray D, Pichel AC, et al. Variations in mortality after emergency laparotomy: The first report of the UK Emergency Laparotomy Network. Brit J Anaesth. 2012;109:368–375. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbas S, Booth M. Major abdominal surgery in octogenarians. N Z Med J. 2003;116:U402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arenal JJ, Bengoechea-Beeby M. Mortality associated with emergency abdominal surgery in the elderly. Can J Surg. 2003;46:111–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arenal-Vera JJ, Tinoco-Carrasco C, del-Villar-Negro A, et al. Colorectal cancer in the elderly: Characteristics and short term results. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:408–415. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082011000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Modini C, Romagnoli F, De Milito R, et al. Octogenarians: An increasing challenge for acute care and colorectal surgeons. An outcomes analysis of emergency colorectal surgery in the elderly. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e312–e318. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pepin J, Vo TT, Boutros M, et al. Risk factors for mortality following emergency colectomy for fulminant Clostridium difficile infection. Dis Colon Rect. 2009;52:400–405. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819a69aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemmer PH, de Schipper JS, van Etten B, et al. Results of surgery for perforated gastroduodenal ulcers in a Dutch population. Digest Surg. 2011;28:360–366. doi: 10.1159/000331320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. The impact of the risk factor “age” on the early postoperative results of surgery for colorectal carcinoma and its significance for perioperative management. World J Surg. 2005;29:1013–1021. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iversen LH, Bulow S, Christensen IJ, et al. Postoperative medical complications are the main cause of early death after emergency surgery for colonic cancer. Brit J Surg. 2008;95:1012–1019. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolfschoten NE, Wouters MW, Gooiker GA, et al. Nonelective colon cancer resections in elderly patients: Results from the Dutch surgical colorectal audit. Digest Surg. 2012;29:412–419. doi: 10.1159/000345614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duron JJ, Duron E, Dugue T, et al. Risk factors for mortality in major digestive surgery in the elderly: A multicenter prospective study. Ann Surg. 2011;254:375–382. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318226a959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finlayson S. Invited commentary. J Am Col Surg. 2014;218:1128–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozlow JH, Berenholtz SM, Garrett E, et al. Epidemiology and impact of aspiration pneumonia in patients undergoing surgery in Maryland, 1999–2000. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1930–1937. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069738.73602.5F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barone A, Giusti A, Pizzonia M, et al. A comprehensive geriatric intervention reduces short- and long-term mortality in older people with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:711–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00668_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CC, Lin MT, Tien YW, et al. Modified hospital elder life program: Effects on abdominal surgery patients. J Am Col Surg. 2011;213:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL. Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ortho Trauma. 2014;28:e49–e55. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182a5a045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deschodt M, Braes T, Broos P, et al. Effect of an inpatient geriatric consultation team on functional outcome, mortality, institutionalization, and readmission rate in older adults with hip fracture: A controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1299–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tillou X, Collon S, Surga N, et al. Comparison of UW and Celsior: Long-term results in kidney transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2013;18:146–152. doi: 10.12659/AOT.883862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelley-Quon L, Min L, Morley E, et al. Functional status after injury: A longitudinal study of geriatric trauma. Am Surg. 2010;76:1055–1058. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Review of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. Section 10.3.2. Including Unpublished Studies in Systematic Reviews [on-line] Available at http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_10/10_3_2_including_unpublished_studies_in_systematic_reviews.htm Accessed May 2, 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.