Abstract

Purpose

Attention to patients' religious and spiritual needs is included in national guidelines for quality end-of-life care, but little data exist to guide spiritual care.

Patients and Methods

The Religion and Spirituality in Cancer Care Study is a multi-institution, quantitative-qualitative study of 75 patients with advanced cancer and 339 cancer physicians and nurses. Patients underwent semistructured interviews, and care providers completed a Web-based survey exploring their perspectives on the routine provision of spiritual care by physicians and nurses. Theme extraction was performed following triangulated procedures of interdisciplinary analysis. Multivariable ordinal logistic regression models assessed relationships between participants' characteristics and attitudes toward spiritual care.

Results

The majority of patients (77.9%), physicians (71.6%), and nurses (85.1%) believed that routine spiritual care would have a positive impact on patients. Only 25% of patients had previously received spiritual care. Among patients, prior spiritual care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 14.65; 95% CI, 1.51 to 142.23), increasing education (AOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.49), and religious coping (AOR, 4.79; 95% CI, 1.40 to 16.42) were associated with favorable perceptions of spiritual care. Physicians held more negative perceptions of spiritual care than patients (P < .001) and nurses (P = .008). Qualitative analysis identified benefits of spiritual care, including supporting patients' emotional well-being and strengthening patient-provider relationships. Objections to spiritual care frequently related to professional role conflicts. Participants described ideal spiritual care to be individualized, voluntary, inclusive of chaplains/clergy, and based on assessing and supporting patient spirituality.

Conclusion

Most patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses value spiritual care. Themes described provide an empirical basis for engaging spiritual issues within clinical care.

INTRODUCTION

Religion and spirituality (R/S) is central to how many patients cope with terminal illness and find hope at the end of life (EOL).1–4 Research has shown that spirituality preserves patients' quality of life (QOL) despite severe physical symptoms,2,5,6 supports prognostic acceptance,7 and protects against hopelessness and despair near death.8 Patients with advanced cancer experience a particularly high burden of spiritual needs,1,9 which may threaten their QOL.10

Spiritual care (SC) recognizes the role of R/S in illness and supports spiritual needs.11,12 Although chaplaincy is a cornerstone of SC, studies indicate that 41% to 94% of patients want their physician to be attentive to R/S,13–15 particularly in the setting of terminal illness.16–18 National palliative care guidelines12,19 recommend multidisciplinary provision of SC, emphasizing the role of physicians and nurses in assessment. R/S has further relevance to medical providers because of its importance to patients' EOL medical decisions.16,20–22 Finally, spiritual support from medical providers is associated with improved QOL,2 satisfaction with medical care,23–25 and lower rates of aggressive EOL care.26 Despite these potential benefits and national guidelines,12,19 engagement of patient spirituality remains controversial27,28 and occurs rarely.2,23

A barrier to SC is the paucity of data to guide its provision and inform clinician education.29 It is unclear what forms of spiritual engagement are acceptable or supportive to patients, and it is also unclear how clinicians can best support R/S within their professional boundaries. Although SC is most relevant to patients at EOL,17,18,30 most research has studied non–terminally ill populations.13,14,16–18,31 Existing research is further limited by over-reliance on quantitative methodology, which is inadequate for generating a nuanced understanding of this topic.

The Religion and Spirituality in Cancer Care (RSCC) Study is a multi-institution, cross-sectional study of patients with advanced cancer, oncology physicians, and nurses that examines perceptions of SC and uses mixed qualitative and quantitative methods.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Sample

Enrollment ran between March 2006 and April 2008 for patients and October 2008 through January 2009 for practitioners. Patient eligibility criteria included diagnosis of an advanced incurable cancer, active receipt of palliative radiation therapy, age 21 years or older, and adequate stamina to undergo a 45-minute interview. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English or Spanish or if they met criteria for delirium or dementia by neurocognitive examination.32 Oncology physicians and nurses were eligible if they cared for patients with incurable cancer.

Study Protocol

Patients and practitioners were recruited from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston University Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, all in Boston, MA. All attending radiation oncologists at participating institutions allowed patient recruitment from their clinic schedule. Radiation oncologists' schedules were sequentially selected for patient recruitment; all eligible patients scheduled within a 1-week period were approached for study participation.

Oncology physicians and nurses were identified from medical, surgical, and radiation oncology departmental Web sites and e-mail databases. Each participating site's institutional review board approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent. The institutional review board–approved “implied informed consent” for practitioners was based on elements of informed consent within the survey. Patients underwent a 45-minute semistructured interview led by a trained research team member. Practitioners were contacted via e-mail and asked to complete a 15-minute Web-based survey. Of 103 patients approached, 75 (response rate, 73%) participated. Five patients were too ill to complete the interview and two omitted the main question analyzed here, yielding 68 (90.7%) of 75 patients. Of 537 physicians and nurses contacted, 339 responded (response rate, 63%; 59% among physicians; 72% among nurses). Eight practitioners indicated that they did not provide care to patients with incurable cancer, and 13 did not finish the questionnaire, yielding 318 (93.8%) of 339 respondents (204 physicians; 114 nurses).

Study Measures

Demographic and clinical variables.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education were reported by the patient. Cancer diagnosis and Karnofsky performance status were obtained from physician assessment. Survival from date of enrollment was obtained from the patients' medical records or the Social Security death index. Practitioners reported sex, age, race/ethnicity, field of oncology, and years of practice.

R/S variables.

Patients and practitioners reported religious tradition and frequency of attendance at religious services. Two items from the Fetzer Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research33 assessed participants' religiousness and spirituality. Pargament's Brief RCOPE (a 14-item measure of religious coping with major life stressors)34 assessed patients' use of positive religious coping (eg, seeking spiritual support, religious forgiveness). Patients were asked if they had ever received SC from a cancer physician or nurse.

SC was defined within the survey as “care that supports a patient's spiritual health,” followed by eight examples (eg, asking about a patient's religious/spiritual background). All participants were then asked, “What if cancer doctors and nurses regularly provided spiritual care? Assume the spiritual care is done in an appropriate, sensitive way . . . [example]. How positive or negative do you think this would be for cancer patients?” Responses ranged from 1 (very negative) to 7 (very positive) on a 7-point Likert scale. These eight spiritual care examples and the full survey question are included in the Data Supplement. In addition, patients and providers explained their response in open-ended fashion. Physicians and nurses provided written explanation whereas patients' responses were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analytic Methods

Quantitative analyses.

Differences between patients', nurses', and physicians' attitudes toward SC were analyzed by using the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections. Fisher's exact test compared attitudes between patients who had versus those who had not previously received SC. The dependent variable was trichotomized (negative, neutral to slightly positive, and moderately to very positive) because of small numbers within individual response categories. Multivariable ordinal logistic regression models using backward selection analyzed relationships between participants' characteristics and attitudes toward SC (the dependent variable). Covariates considered in patient models included sex, race, education, marital status, income, religious tradition, religious service attendance, spirituality (moderately or very spiritual v slightly or not at all spiritual), religious coping (median split), and patients' prior receipt of spiritual care (yes or no). Covariates tested in physician and nurse models included sex, age, race, religious tradition, religious service attendance, and spirituality. Religiousness was omitted because of colinearity with spirituality. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values were two-sided and were considered significant at less than .05.

Qualitative analysis.

The protocol followed rigorous qualitative methodology—triangulated analysis, employment of multidisciplinary perspectives, and reflexive narratives—to maximize the transferability of interview data. Transcriptions were independently coded by A.C.P. and J.D. and were compiled into two preliminary coding schemes. Following principles of grounded theory, a final set of themes and subthemes emerged through an iterative process with input from A.C.P., J.D., M.T.B., and T.A.B. Transcripts were then independently recoded by S.A. and M.V.W. The inter-rater reliability score was high (κ = 0.9). Frequency of themes endorsed by patients, physicians, and nurses were compared by using χ2 or Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

Quantitative Assessment of Spiritual Care Perceptions

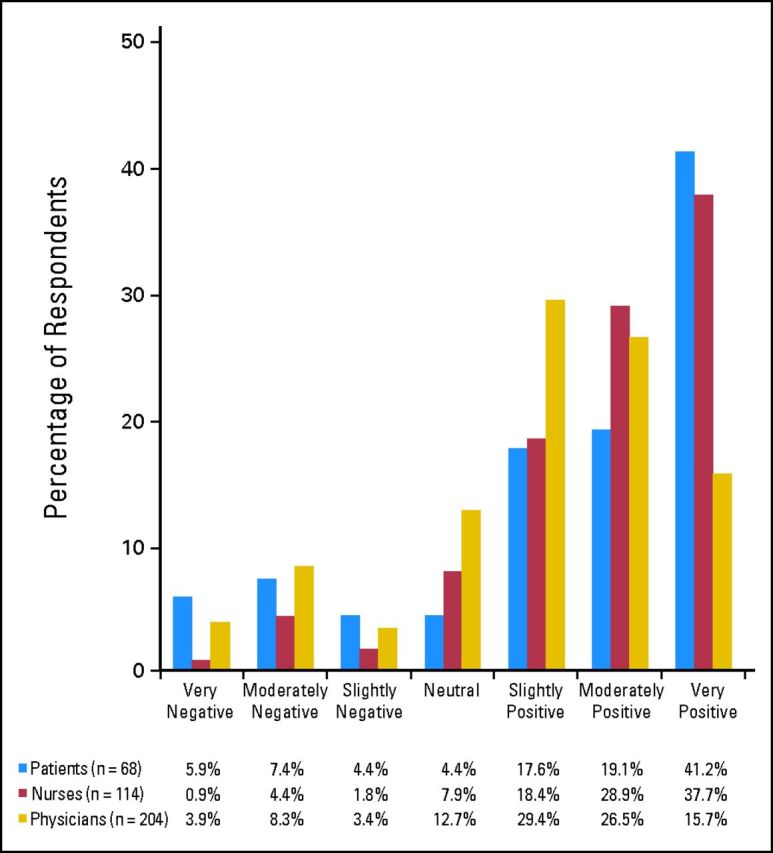

Sample characteristics are listed in Table 1. The majority of patients (53 of 68; 77.9%), physicians (146 of 204; 71.6%), and nurses (97 of 114; 85.1%) reported that regular provision of SC by physicians or nurses would be at least slightly positive for patients (Fig 1). Physicians' perceptions were significantly more negative than those of patients (P = .008) and nurses (P < .001). A notable proportion of patients (12 of 68; 17.6%), physicians (32 of 204; 15.7%), and nurses (eight of 114; 7%) thought that routine SC would have a negative impact on patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients With Cancer, Oncology Physicians, and Oncology Nurses

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 68) |

Physicians (n = 204) |

Nurses (n = 114) |

P* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | Mean | SD | No. | % | Mean | SD | No. | % | Mean | SD | ||

| Female sex | 32 | 47.1 | 86 | 42.0 | 112 | 98.2 | < .001 | ||||||

| Age, years | 60.2 | 11.9 | 40.9 | 9.9 | 45.4 | 9.2 | < .001 | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| White | 57 | 83.8 | 155 | 76.0 | 108 | 94.7 | |||||||

| Black | 7 | 10.3 | 4 | 2.0 | 2 | 1.8 | |||||||

| Asian American, Indian, Pacific Islander | 1 | 1.5 | 35 | 17.2 | 2 | 1.8 | |||||||

| Hispanic | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.9 | |||||||

| Other | 2 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | < .001 | ||||||

| Education | 15.2 | 3.4 | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Religiousness | |||||||||||||

| Not at all religious | 13 | 19.1 | 62 | 30.4 | 29 | 25.4 | |||||||

| Slightly religious | 25 | 36.8 | 66 | 32.4 | 33 | 28.9 | |||||||

| Moderately religious | 17 | 25.0 | 54 | 26.5 | 43 | 37.7 | |||||||

| Very religious | 13 | 19.1 | 17 | 8.3 | 7 | 6.1 | .02 | ||||||

| Spirituality | |||||||||||||

| Not at all spiritual | 5 | 7.4 | 30 | 14.7 | 6 | 5.3 | |||||||

| Slightly spiritual | 14 | 20.6 | 57 | 27.9 | 18 | 15.8 | |||||||

| Moderately spiritual | 24 | 35.3 | 75 | 36.8 | 58 | 50.9 | |||||||

| Very spiritual | 25 | 36.8 | 37 | 18.1 | 30 | 26.3 | < .001 | ||||||

| Religious tradition | |||||||||||||

| Catholic | 32 | 47.1 | 47 | 23.0 | 70 | 61.4 | |||||||

| Other Christian traditions | 22 | 32.4 | 45 | 22.1 | 17 | 14.9 | |||||||

| Jewish | 5 | 7.4 | 51 | 25.0 | 6 | 5.3 | |||||||

| Muslim | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Hindu | 2 | 2.9 | 3 | 1.5 | 2 | 1.8 | |||||||

| Buddhist | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5.4 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| No religious tradition | 2 | 2.9 | 22 | 10.8 | 6 | 5.3 | |||||||

| Other | 4 | 5.8 | 18 | 8.8 | 11 | 9.6 | < .001 | ||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | |||||||||||||

| Lung | 23 | 33.8 | — | — | |||||||||

| Breast | 10 | 14.7 | — | — | |||||||||

| Colorectal | 6 | 8.8 | — | — | |||||||||

| Hematologic/lymphoma | 11 | 16.2 | — | — | |||||||||

| Prostate | 5 | 7.4 | — | — | |||||||||

| Melanoma | 2 | 2.9 | — | — | |||||||||

| Other | 11 | 16.2 | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Karnofsky performance status | 70 | 20.6 | — | — | |||||||||

| Survival, days | 175.5 | 311.2 | — | — | |||||||||

| Field of oncology | |||||||||||||

| Medical | — | 110 | 53.9 | 90 | 78.9 | ||||||||

| Radiation | — | 46 | 22.5 | 13 | 11.4 | ||||||||

| Surgical | — | 32 | 15.7 | 7 | 6.1 | ||||||||

| Palliative care | — | 16 | 7.8 | 4 | 3.5 | < .001 | |||||||

| Years in practice | |||||||||||||

| Resident or fellow | — | 67 | 32.8 | — | |||||||||

| 1-5 | — | 35 | 17.2 | 24 | 21.1 | ||||||||

| 6-10 | — | 34 | 16.7 | 24 | 21.1 | ||||||||

| 11-15 | — | 23 | 11.3 | 14 | 12.3 | ||||||||

| 16-20 | — | 20 | 9.8 | 11 | 9.6 | ||||||||

| 21+ | — | 25 | 12.3 | 41 | 36.0 | — | |||||||

NOTE. Because of missing data, percentages may not add up to 100.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

χ2 tests used for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Fig 1.

Attitudes toward spiritual care among patients with cancer, oncology physicians, and oncology nurses. Differences between patients,' nurses,' and physicians' responses were tested with a Kruskal-Wallis test, yielding P < .001. Pairwise comparisons between patient and physician and between physician and nurse were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Bonferroni corrections; P = .008 and P < .001, respectively.

Previous receipt of SC was significantly associated with a favorable perception of routine SC (P = .012; Table 2). In multivariable patient models, increasing education (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.26; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.49; P = .009), religious coping (AOR, 4.79; 95% CI, 1.40 to 16.42; P = .013), and previous SC (AOR, 14.65; 95% CI, 1.51 to 142.23; P = .021) were significantly associated with positive perceptions of SC. Other patient characteristics were unrelated to perceptions of SC.

Table 2.

Patients' Rating of Routine Spiritual Care According to Receipt of Previous Spiritual Care From an Oncology Physician or Oncology Nurse

| Spiritual Care Rating | Receipt of Spiritual Care Before Survey* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 48) |

Yes (n = 16) |

|||

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Negative | 11 | 22.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Neutral to slightly positive | 12 | 25 | 1 | 6.2 |

| Moderately or very positive | 25 | 52 | 15 | 93.8 |

Fisher's exact test (P = .012).

In multivariable physician models, younger age (AOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.09; P < .001) and spirituality (AOR, 5.39; 95% CI, 2.89 to 10.08; P < .001) were associated with positive perceptions of SC. No characteristics of nurses were significantly associated with perceptions of SC in univariate or multivariate analyses.

Qualitative Spiritual Care Themes

Three primary themes were identified within respondents' open-ended explanations of their perspectives toward SC (Table 3): (1) potential effects of SC on patients and/or the patient-provider relationship, (2) attitudes toward SC in the clinical care of patients with cancer, and (3) characteristics of appropriate SC delivery. Frequency of spiritual care themes and subthemes are reported in Table 4.

Table 3.

Main Spiritual Care Themes with Representative Quotations

| Spiritual Care Theme | Representative Quotation |

|---|---|

| Effects on patients | |

| Positive effects |

|

| Negative effects |

|

| Conditional effects |

|

| Attitudes toward spiritual care | |

| Positive attitudes |

|

| Negative attitudes |

|

| Delivery of spiritual care | |

| Individualized to patient |

|

| Voluntary for patient and provider |

|

| Include chaplains or clergy |

|

| Content of spiritual care |

|

Table 4.

Frequencies of Qualitative Spiritual Care Themes Among Patients With Advanced Cancer, Oncology Physicians, and Oncology Nurses

| Spiritual Care Theme | Patients (n = 66) |

Physicians (n = 202) |

Nurses (n = 112) |

P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Effects on patients | |||||||

| Positive effects | 37 | 56 | 69 | 34 | 48 | 43 | .006 |

| Patient well-being | 20 | 30† | 15 | 7 | 20 | 18‡ | < .001 |

| Patient-provider relationship | 7 | 11 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 4 | .013 |

| Negative effects | 8 | 12 | 23 | 11 | 12 | 11 | .959 |

| Patient offense | 1 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 6 | .369 |

| Patient-provider relationship | 1 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 4 | .851 |

| Conditional effects | 23 | 35 | 60 | 30 | 33 | 29 | .703 |

| Conditional on patient | 19 | 29‡ | 46 | 23† | 27 | 24† | .612 |

| Conditional on spiritual care delivery | 7 | 11 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 7 | .665 |

| Predisposing attitudes | |||||||

| Positive attitudes | 16 | 24 | 33 | 16 | 36 | 32 | .005 |

| Holistic care | 7 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 11 | .040 |

| Religion/spirituality is important to many patients | 5 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 7 | .203 |

| Cancer evokes spiritual needs | 10 | 15 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 6 | .011 |

| Negative attitudes | 16 | 24 | 72 | 36 | 24 | 21 | .018 |

| Professional role | 10 | 15§ | 54 | 27¶ | 15 | 13 | .009 |

| Religion/spirituality is a private matter | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | .148 |

| Religion/spirituality and medicine should be separate | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 4 | .924 |

| Delivery of spiritual care | |||||||

| Individualized to each patient | 11 | 17 | 14 | 7 | 16 | 14§ | .031 |

| Voluntary for patient and provider | 9 | 14 | 14 | 7 | 13 | 12 | .074 |

| Include chaplains or clergy | 6 | 9 | 30 | 15§ | 10 | 9 | .217 |

| Content of spiritual care | 21 | 32¶ | 36 | 18‡ | 29 | 26† | .038 |

| Religion/spirituality assessment | 11 | 17 | 23 | 11 | 19 | 17 | .307 |

| Support patient's religion/spirituality | 6 | 9 | 19 | 9 | 17 | 15 | .252 |

| No proselytizing or spiritual counsel | 6 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | .194 |

| Prayer | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | .685 |

P value obtained from χ2 test or fisher's exact test.

Most frequently endorsed subtheme.

Second most frequently endorsed subtheme.

Third most frequently endorsed subtheme.

Fourth most frequently endorsed subtheme.

Within the effects of SC theme, participants most frequently noted its potential benefits (154 of 380) on patient well-being (55 of 380) and the patient-provider relationship (21 of 380). SC was proposed to benefit patient well-being through providing emotional, psychological, and spiritual support, with rare comments mentioning benefits to physical health. One patient commented, “I think it is an opportunity for the patient and the doctor to enhance their relationship with each other and with God. I think it would be a comforting experience. I think that it would be kind, and it might give the cancer patient more opportunities to receive something that the cancer has taken away. Because let's face it, cancer is about loss, so it [spiritual care] is a way of replenishing wealth.” Possible negative effects of SC (43 of 380) included the potential to offend patients or to harm the patient-provider relationship. Many participants (116 of 380) noted that the effects of SC are not uniformly beneficial or harmful but are conditional on each patient and provider. One patient who rated routine SC as very positive warned, “If the person isn't spiritual . . . it could really make a conflict for them . . . I mean you can ask, and if they say no, then that's it. Drop it.” A physician explained, “This may support some religious patients. In other cases, patients may be put off in that they would think their oncologist is turning to spiritual guidance as they do not have effective medical therapies.”

Participants expressed both positive and critical attitudes regarding the role of SC in medical practice. Positive attitudes (85 of 380) included the belief that physicians and nurses should treat the whole person, that R/S is important to many patients, and that cancer evokes spiritual needs. One physician stated, “I think attention to meaning and spirituality is missing in many aspects of our culture and society. It is particularly important for those facing death or serious illness.” Several participants framed their responses within a holistic philosophy of care. “It represents the holistic nature of nursing . . . [if a patient says]“I am an atheist, but my family was very religious,' this gives the nurse a great deal of useful information for individualized end-of-life care.” A patient explained, “When talking about healing and taking care of patients, [physicians and nurses] have to think about the body, the mind, and spirituality. Think of the person as a whole.”

Some respondents articulated critical attitudes toward SC (81 of 380). More than one quarter of physicians (54 of 202) suggested that SC was outside their professional role and training. “It's not really our role to provide this care. We're not trained in it and there are others available who would be better.” Similarly, a patient stated, “I don't think most doctors have background or education in religion or spirituality. I don't think that's why patients seek them out . . . The time that doctors have with patients is very short, and there is a struggle to get enough time to even discuss medical issues in a way that is clear and helpful.” Some of the other criticisms included that R/S is a private matter and the belief that spirituality and medical care should remain separate.

The third theme identified—appropriate delivery of SC—was defined as the necessary characteristics of SC. Many participants commented on the ideal content of SC (86 of 380), which included assessing patient R/S (45 of 380), supporting patients' spiritual beliefs and needs (33 of 380), and avoiding proselytizing or spiritual counseling (16 of 380). One patient reflected on the benefits of spiritual assessment, “I think that doctors . . . would encourage patients to express their spiritual problems and especially the fear of death and the other side, and patients wouldn't feel so afraid, and that stuff would not be untouched.” A physician commented “I think it is fine to ask a patient about their religious/spiritual background . . . but spiritual guidance should be directed by a chaplain.” Other characteristics of appropriately delivered SC included involving chaplains/clergy (46 of 380), individualizing care to each patient (41 of 380), and ensuring that SC is voluntary for both patients and providers (36 of 380).

Examination of theme frequencies revealed notable differences between the perspectives of patients, physicians, and nurses (Table 4). Recognition of the positive effects of SC differed significantly among respondents (P = .006). For example, only 7% of physicians cited specific benefits of SC to patients' well-being compared with 30% of patients and 18% of nurses (P < .001). Patients, physicians, and nurses also expressed differing frequencies of positive attitudes (P = .005) and negative attitudes (P = .018) toward SC, with physicians being the most critical. The four most frequent subthemes cited by patients, physicians, and nurses also differed (Table 4), with physicians more often expressing reservations about their own involvement in SC and preferring to defer to chaplains/clergy.

DISCUSSION

This study provides an in-depth examination of the perspectives of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses regarding engagement of spirituality within the medical care of patients with advanced cancer. The majority of patients (77.9%), physicians (71.6%), and nurses (85.1%) believed that routine SC would at least slightly benefit patients. These attitudes compare somewhat favorably to those in other reports,13,14,16,23,31 possibly because our survey question presupposed sensitive engagement of spiritual issues and pertained to EOL care—the setting in which patients consider spirituality most relevant.16–18 Participants described SC as a source of emotional support, comfort, and a means to validate the spiritual dimensions of terminal illness. Despite these generally favorable perspectives, only 25% of patients had previously received SC. Some participants, especially physicians, expressed skepticism about the compatibility of medical and spiritual caregiving roles. Overall, our findings support attention to patients' spirituality within national guidelines for quality EOL care,12,19 while highlighting some complexities inherent to addressing R/S within clinical care.

SC was proposed to benefit patients by supporting their spiritual and emotional needs. This is in keeping with prior research demonstrating the centrality of R/S to patients' ability to cope with3,5,6 and accept terminal illness7 and find meaning at the EOL.4,8 R/S traditions offer teachings about hope, suffering, and life after death which can be profoundly relevant and comforting to patients with advanced illness.4,15 Patients' previous receipt of SC was strongly associated with positive perceptions of routine SC. This association might reflect the propensity of religious/spiritual patients to have received SC; however, persistence of this association in multivariable models that include R/S characteristics suggests an effect of prior SC beyond confounders. Other studies confirm that SC is associated with patients' satisfaction with care23–25 and improved QOL.2,26 Consistent with one study from the family practice literature,18 SC was also described to potentially strengthen patient-provider relationships by demonstrating personal care beyond professional obligation and enhancing providers' understanding of their patients.

An important minority of participants thought SC would be harmful. These viewpoints were often supported by categorical objections based on the privacy of R/S or a belief that spirituality and medicine are completely immiscible. Such objections should always be respected, and patients should retain control over the content and extent of R/S conversations with their providers. Less fundamental reservations about SC were much more common, including consideration for nonreligious patients, concerns about adequate clinician training and discordance of patient/provider beliefs, and recognition that complex spiritual matters are beyond most medical providers' expertise and scope of practice. Appreciation of these challenges was frequent, even among participants who rated routine SC favorably. When interpreted in context, these criticisms seldom reflected disapproval of SC but demonstrated a balanced understanding of its potential benefits, risks, and limitations. Furthermore, 30% of participants emphasized the theme of conditionality: SC was not viewed as uniformly helpful or harmful; rather, its effects were felt to be dependent on each patient, provider, and situation. In summary, although most patients and providers value SC, they also recognize the challenges and limitations of attending to patient spirituality within EOL care.

Although this specific analysis was not designed to comprehensively evaluate SC content, many participants offered their perspectives on this subject. Assessing and supporting patient R/S was described most commonly, with infrequent reference to prayer35 or other particularly religious forms of care. These findings are consistent with an exploratory study from Daaleman et al36 and affirm the emphasis of spiritual assessment within existing guidelines.12,19 A spiritual history can be obtained within a few minutes,37 and may uncover important issues that would benefit from chaplaincy involvement. Moreover, spiritual assessment fosters an environment open to sharing the existential, spiritual, and religious dimensions of illness.9 Our data further suggest that SC should be individualized to each patient and include clergy/chaplains. SC should be entirely voluntary and not supersede good medical care, nor should clinicians proselytize. These cautionary points are self-evident and consistent with national guidelines.12 In synthesis, participants largely described a model of SC founded within patient-provider relationships open to sharing and supporting the spiritual dimensions of terminal illness in a patient-centered manner.

Strengths of this study include use of quantitative and qualitative methodology, which are both necessary to provide a nuanced understanding of SC. In addition, this study enrolled the population shown to most want SC—those with terminal illness.16,17 Limitations include recruitment from a single geographic region and limited ethnic diversity of patients. Given the relatively low religiousness/spirituality within the Northeast, national attitudes may be more favorable. Because qualitative research is limited by what participants spontaneously share, themes are likely underestimated, and therefore theme frequencies and differences identified between patients and providers should be considered hypothesis generating.

In summary, most patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses believe routine SC would benefit patients. Our data suggest that SC, when offered appropriately and sensitively, could significantly enrich patients' emotional well-being and patient-provider relationships. Although physicians were particularly attuned to tensions between SC and professionalism, the patient-centered and circumscribed vision of SC described here seems at minimal odds with clinical responsibilities. Considering the infrequency of SC reported here and elsewhere,2,16,23 physicians and nurses might be neglecting an important opportunity to improve the care of patients with advanced cancer.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Andrea C. Phelps, Michael T. Balboni, Tracy A. Balboni

Financial support: Tracy A. Balboni

Administrative support: Tracy A. Balboni

Collection and assembly of data: Katharine E. Lauderdale, Michael T. Balboni, Tracy A. Balboni

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcorn SR, Balboni MJ, Prigerson HG, et al. “If God wanted me yesterday, I wouldn't be here today”: Religious and spiritual themes in patients' experiences of advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:581–588. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulmasy DP. Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients: “ . . . it's okay between me and god.”. JAMA. 2006;296:1385–1392. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.11.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, et al. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology. 1999;8:417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Tomas JJ, et al. Existential well-being is an important determinant of quality of life: Evidence from the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. Cancer. 1996;77:576–586. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960201)77:3<576::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson GN, Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, et al. Prognostic acceptance and the well-being of patients receiving palliative care for cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5757–5762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet. 2003;361:1603–1607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moadel A, Morgan C, Fatone A, et al. Seeking meaning and hope: Self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population. Psychooncology. 1999;8:378–385. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<378::aid-pon406>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkelman WD, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. The relationship of spiritual concerns to the quality of life of advanced cancer patients: Preliminary findings. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1022–1028. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daaleman TP, Usher BM, Williams SW, et al. An exploratory study of spiritual care at the end of life. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:406–411. doi: 10.1370/afm.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King DE, Bushwick B. Beliefs and attitudes of hospital inpatients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maugans TA, Wadland WC. Religion and family medicine: A survey of physicians and patients. J Fam Pract. 1991;32:210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulmasy DP. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002;42:24–33. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehman JW, Ott BB, Short TH, et al. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1803–1806. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacLean CD, Susi B, Phifer N, et al. Patient preference for physician discussion and practice of spirituality. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:38–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCord G, Gilchrist VJ, Grossman SD, et al. Discussing spirituality with patients: A rational and ethical approach. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:356–361. doi: 10.1370/afm.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, Second Edition 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140–1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silvestri GA, Knittig S, Zoller JS, et al. Importance of faith on medical decisions regarding cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1379–1382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, et al. Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: The role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:174–179. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Astrow AB, Wexler A, Texeira K, et al. Is failure to meet spiritual needs associated with cancer patients' perceptions of quality of care and their satisfaction with care? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5753–5757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, et al. Spiritual care of families in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1084–1090. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259382.36414.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams JA, Meltzer D, Arora V, et al. Attention to inpatients' religious and spiritual concerns: Predictors and association with patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1265–1271. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1781-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: Associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:445–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sloan RP, Bagiella E, Powell T. Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet. 1999;353:664–667. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sloan RP, Bagiella E, VandeCreek L, et al. Should physicians prescribe religious activities? N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1913–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King DE, Crisp J. Spirituality and health care education in family medicine residency programs. Fam Med. 2005;37:399–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monroe MH, Bynum D, Susi B, et al. Primary care physician preferences regarding spiritual behavior in medical practice. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2751–2756. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daaleman TP, Nease DE., Jr Patient attitudes regarding physician inquiry into spiritual and religious issues. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:564–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fetzer Institute: Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research: A Report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balboni MJ, Babar A, Dillinger J, et al. “It depends”: Viewpoints of patients, physicians, and nurses on patient-practitioner prayer in the setting of advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:836–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanson LC, Dobbs D, Usher BM, et al. Providers and types of spiritual care during serious illness. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:907–914. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrell B. Meeting spiritual needs: What is an oncologist to do? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:467–468. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.