Abstract

Carbohydrate-conjugated fluorescent silica nanoprobes were prepared and used as a platform for galectin-1 and prostate cancer cell detection. The nanoparticles were efficiently conjugated using native, unprotected carbohydrate structures following a photochemical approach, resulting in lactose- and cellobiose-conjugated probes, respectively. The probes were used to challenge binding to galectin-1, an overexpressed galactose-selective lectin at prostate cancer cell surfaces, and the results show that lactose-conjugated nanoprobes exhibit differential binding behavior with prostate cancer cells and normal prostate cells. In particular, lactose-conjugated fluorescent silica nanoparticles showed specific binding to PC3 cells pre-treated with a reducing agent. The results indicate that galectin-1 expression and galectin-1-selective nanoparticles are potentially useful for sensitive and selective detection of prostate cancer.

Keywords: Fluorescence, Silica nanoparticle, Galectin, Carbohydrate, Prostate cancer

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is a leading cause of death among men, and the second most fatal cancer form in the United States [1]. Early and accurate diagnosis is key to effective and ultimately successful treatment of prostate cancer, and sensitive and selective diagnostic methods are increasingly important. To this end, new technologies based on bio-functionalized nanomaterials constitute a particularly promising platform, demonstrated in extensive biological applications [2]. Generally, nanomaterials possess unique chemical and physical properties that enable efficient bio-imaging, targeting and drug delivery [3]. For example, color changes associated with the aggregation of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have led to the development of colorimetric assays for a variety of target species [4–8]. Semiconductor nanoparticles or quantum dots (QDs) have also been widely used in fluorescence-based bio-labeling and imaging applications at the subcellular length scales [9]. However, these materials are generally cytotoxic and require complex treatment such as surface coating or functionalization with non-cytotoxic species for in vivo and in vitro applications.

Silica nanoparticles (SNPs), on the other hand, are hydrophilic as prepared, of low cytotoxicity and readily applicable to in vitro studies. Studies have also shown that SNPs can be efficiently modified for improved biocompatibility in vivo [10]. The easily accessible surface chemistry of silica makes it easy to modify with biomolecules [11]. Particularly, when the fluorophore is embedded in SNPs, the silica matrix works as a protective shell to isolate the fluorophore from the outside environment, thereby greatly enhancing the photostability of fluorophores [12]. In addition, a large number of fluorophores can be encapsulated inside a single nanoparticle, which produces a strong fluorescence signal following adequate excitation. Dye-doped SNPs have been functionalized to detect DNA [13], label human lung adenocarcinoma cells (in vitro) and rat brain tissue (in vivo) [14]. In this study, fluorescent silica nanoparticles (FSNPs) were synthesized and the subsequent functionalization was undertaken to endow FSNPs the ability to detect prostate cancer cells through specific carbohydrate-protein interactions.

Galectins are a family of carbohydrate-binding proteins with an affinity for β-galactosides. Galectin-1 (Gal-1), the first identified galectin family member, is a dimeric carbohydrate binding protein (14 kDa) that has been suggested to play an important role in the development and progression of cancer [15]. Gal-1 is over-expressed on prostate cancer cells and is the only galectin which expresses on cell surfaces [16]. Consequently, over-expressed Gal-1 can be employed as a biomarker for prostate cancer cell detections through carbohydrate-protein interactions. Generally, carbohydrate-protein interactions are characterized by relatively low binding affinities. However, the low affinity can be compensated for by presentation of multiple ligands to individual receptors [17]. Due to their high surface-to-volume ratios, nanoparticles possess the ability to present high densities of carbohydrate ligands on their surfaces, thereby greatly enhancing the weak affinity of individual ligands to their binding acceptors. For example, the apparent Kd of D-mannose-conjugated AuNPs with Con A can be as low as 0.43 nM, representing a binding affinity of over six orders of magnitude higher than for free D-mannose with Con A [18,19]. These results indicate that nanoparticles are excellent materials for amplifying the weak affinities of carbohydrate ligands with lectins.

Currently, the most direct approach to create stable carbohydrate-conjugated nanoparticles is through covalent attachment by either chemisorption or heterobifunctional linkers [20], such as thiolated carbohydrates on metal or semiconductor nanoparticles (Au, Ag, CdS, CdSe/ZnS) [8, 21–27]. These coupling methods, however, often require complex chemical derivatization schemes of the carbohydrates where multiple protection/deprotection and glycosylation reactions are involved. Hence, coupling chemistries that do not require chemical derivatization of the carbohydrates are highly appealing. In one approach, hydrazide-modified gold substrates were used the form acyl hydrazones with the terminal aldehyde group of the carbohydrates [28, 29]. In another strategy, amine-functionalized surfaces were employed and coupling of the carbohydrates were achieved by reductive amination to yield amine conjugates [30, 31]. In both cases, however, the coupled products often lost their binding affinities after conjugation. We have developed a novel coupling chemistry that takes advantage of the photochemistry of azides, which becomes reactive nitrenes upon light activation and readily inserts into CH-bonds, creating highly robust covalent linkages. In particular, perfluorophenylazides (PFPAs) have been employed as photoaffinity labels to prepare azide-functionalized nanoparticles that can subsequently be coupled with, in principle, any carbohydrate structures by way of the insertion reactions of photochemically activated nitrene species [32, 33]. In this study, fluorescent silica nanoparticles were functionalized with PFPAs and conjugated with carbohydrates. Subsequently, the interactions of the carbohydrate-conjugated nanoparticles with Gal-1 and prostate cancer cells were investigated to evaluate the potential applications of this nanotechnology platform for prostate cancer cell detections.

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Synthesis of carbohydrate-conjugated fluorescent silica nanoparticles

The FSNPs were prepared using a modified Stöber method as previously described [34–36]. Briefly, fluorescein-silane, synthesized from fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane, was mixed with tetraethoxylsilane (TEOS) in 200-proof ethanol to which NH4OH (25%) was added. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 8 h at ambient temperature under vigorous stirring, yielding a bright yellow colloidal Stöber solution. PFPA-silane, synthesized following a previously reported procedure [37], was subsequently added and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature overnight, followed by refluxing for 1 h. The resulting functionalized silica nanoparticle suspension was centrifuged (10 min, 8000 rpm) and was re-dispersed in solvent using sonication. This centrifugation/re-dispersion procedure was repeated three times using ethanol and twice using acetone.

The resulting PFPA-functionalized FSNPs were dispersed in acetone, to which an aqueous lactose solution was added. The dispersion was irradiated at >280 nm with a 450 W medium pressure Hg lamp for 10 min under vigorous stirring. Following centrifugation and dialysis, the resulting carbohydrate-conjugated FSNPs were exposed to BSA (0.3 wt%) at 4 °C for 1 h. The blocked FSNPs were finally washed by Milli-Q water through repeated re-dispersion, sonication and centrifugation. Cellobiose-conjugated FSNPs were prepared using the same protocol. The functionalized FSNPs were characterized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS).

2.2. Fluorescence cell imaging and intensity measurements

Typically, 1×106 cells were cultured in a tissue culture dish and stored in an incubator for 2 days. After removal of the growth medium, the cells were washed with PBS three times and the carbohydrate-conjugated FSNPs were added. For experiments addressing the influence of DTT in the interactions between the FSNPs and the cells, the cells were pretreated with DTT-containing PBS before incubation with the nanoparticle solutions. After incubation, a portion of the supernatant was withdrawn and the fluorescence intensity measured relative to the original solutions before incubation. The cells were subsequently washed with HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. To measure the fluorescence intensity of cells bound with carbohydrate-conjugated FSNPs, cells were detached from the tissue culture dish by trypsinization. After centrifugation and removal of trypsin, cells were washed and re-suspended in HEPES solutions. The fluorescence intensities of the cells were then measured by spectrofluorometry at excitation of 488 nm.

2.3. Western-blotting analysis

500 ng of Gal-1 was mixed with lactose-conjugated FSNPs (30 μL) at 4 °C for 1 h. The concentrations of the nanoparticle solution varied from 0.17 to 3400 μg/mL. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm (4 °C) for 10 min, 25 μL of supernatant was subjected to electrophoresis on a 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked at room temperature for 1 h with a blocking buffer and incubated with mouse monoclonal antibodies to Gal-1 overnight at 4 °C. After being washed with Milli-Q water three times, the membrane was incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. After drying, the dye-labeled membrane was then imaged by an infrared imaging system. The weight of Gal-1 bound to FSNPs was calculated by measuring the optical densities of each blot and the subsequent normalizations with control samples, which contained 500 ng of Gal-1 not treated with FSNPs.

3. Results and Discussion

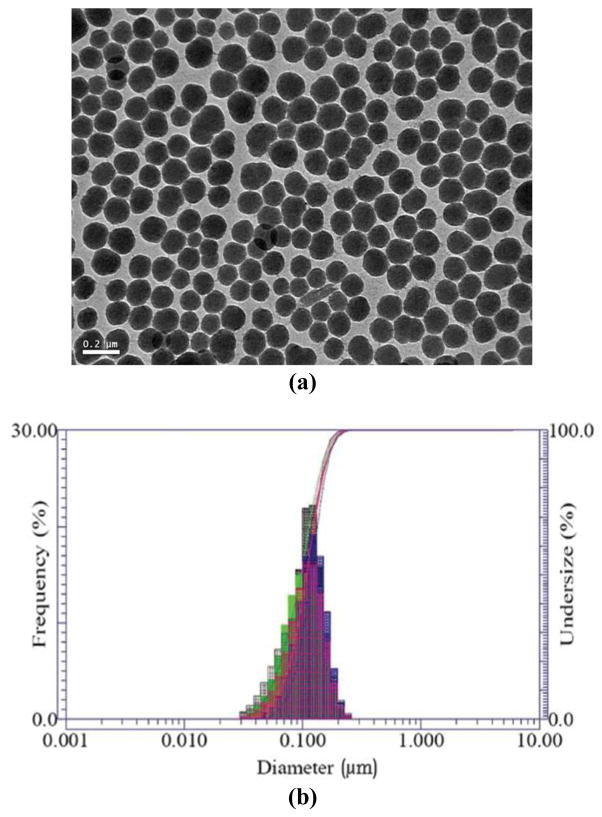

The FSNPs were synthesized by a modified Stöber reaction, and derivatized with a perfluorophenylazide silane (PFPA-silane) [34, 36]. As shown in Figure 1, the as-prepared FSNPs had an average diameter of ca. 100 nm as determined by TEM and DLS. Subsequent functionalization was performed by treating the FSNPs with PFPA-silane, after which the PFPA-functionalized FSNPs were mixed with the carbohydrate solution and irradiated with UV light (>280 nm) to conjugate the carbohydrate to the FSNPs.

Figure 1.

(a) TEM image (scale bar = 0.2 μm) and (b) DLS histogram of FSNPs.

Binding of the carbohydrate-conjugated FSNPs to prostate cancer cells (PC3) was examined by mixing the nanoparticles with PC3 cells, which were attached at the bottom of tissue culture plates. In these experiments, benign hyperplastic prostatic epithelial cells (BPH1) were used as a control cell line, and cellobiose was used as a control ligand with the same chemical formula but different structure with that of lactose, a specific binding carbohydrate for Gal-1. Nanoparticle surfaces were blocked by bovine serum albumin (BSA) to avoid non-specific binding. After incubation, a portion of the supernatant was withdrawn and the fluorescence intensity measured, and compared to that of the original solutions before incubation. In addition, cells were washed with HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. When the nanoparticle surfaces were not blocked with BSA, both lactose- and cellobiose-conjugated FSNPs bound to PC3 cells, and lactose-conjugated nanoparticles also bound to BPH1 cells. However, when the nanoparticle surfaces were blocked with BSA, the non-specific binding was significantly reduced. The observations suggested that the non-specific binding was dominant when the nanoparticle surfaces were not blocked with BSA.

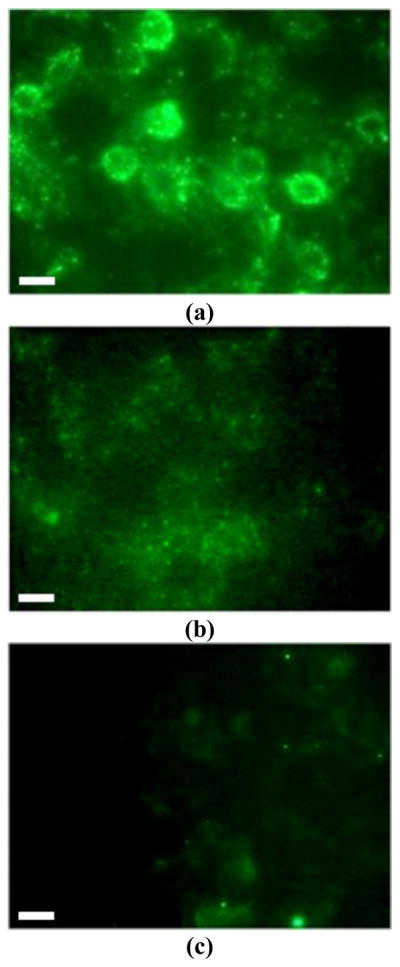

Another important factor for efficient and specific binding between the cells and the lactose-conjugated FSNPs is the thiol oxidation state of Gal-1. Disulfide formation can be detrimental for Gal-1 binding, and maintaining a reduced state is important to conserve the activated form of Gal-1 [38, 39]. Consequently, the role of dithiothreitol (DTT) in improving interactions between the carbohydrate-conjugated FSNPs and the prostate cancer cells was investigated. As a widely-used reducing agent, DTT prevents both intra-molecular and intermolecular disulfide bonds from forming between cysteine residues of Gal-1. As shown in Figure 2a, the interaction of lactose-conjugated FSNPs (blocked with BSA) with PC3 cells was clearly visible after the cells were pretreated with DTT. Most of the FSNPs were attached to the cell surfaces, while some internalization into the cells may have occurred as well. In control experiments, non-conjugated FSNPs showed much lower extent of binding to PC3 cells (Figure 2b), while lactose-conjugated FSNPs also showed greatly reduced binding to BPH1 (Figure 2c). These results indicate that lactose-conjugated FSNPs could specifically bind to prostate cancer cells under appropriate conditions.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence microscope images of (a) lactose-conjugated FSNPs treated with PC3; (b) non-conjugated FSNPs treated with PC3; (c) lactose-conjugated FSNPs treated with control cells BPH1. Concentration of FSNP solution: 34 μg/mL. The images were acquired at 488 nm excitation. Scale bar: 10 μm.

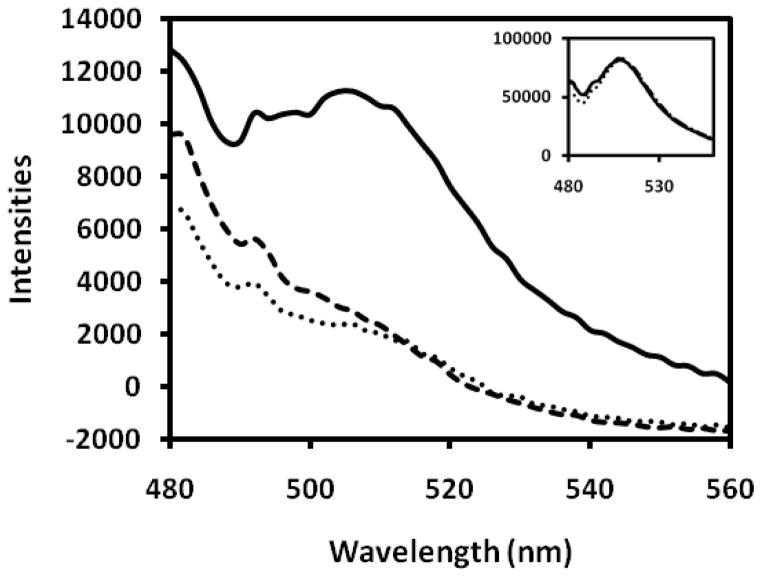

The specific binding of lactose-conjugated FSNPs to prostate cancer cells in the presence of DTT was further confirmed by the measurement of fluorescence intensities of nanoparticle-bound cells by a spectrofluorometry. Figure 3 shows that PC3 cells exhibited higher fluorescence intensities upon interaction with lactose-conjugated FSNPs, compared to cellobiose-conjugated or non-conjugated FSNPs, indicating the specific binding of lactose-conjugated FSNPs to PC3 cells.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence intensity of PC3 cells interacting with FSNPs: (—) lactose-conjugated FSNPs; (---) cellobiose-conjugated FSNPs; (···) non-conjugated FSNPs. Inset shows the fluorescence spectra (emission scan, at 488 nm excitation) of original nanoparticle solutions.

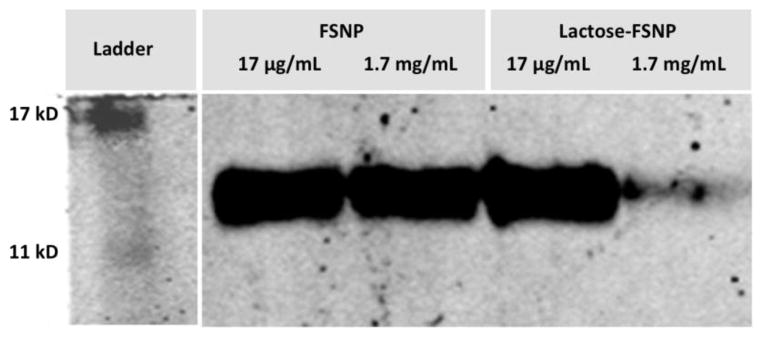

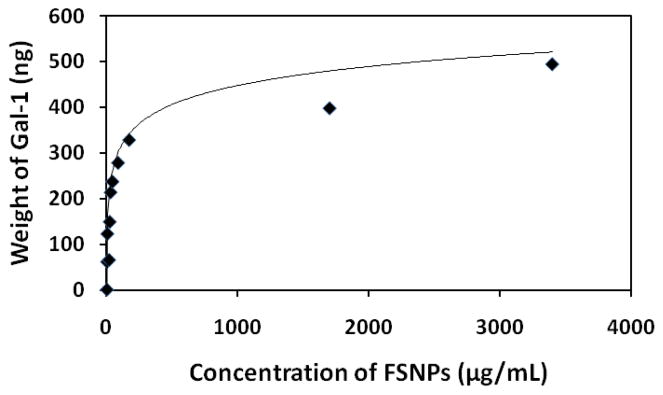

Another proof-of-concept of the specific binding between lactose-conjugated FSNPs and Gal-1 was established by western-blotting, a widely-used electrophoretic method for studying expressions of specific proteins [40]. In principle, binding of lactose-conjugated FSNPs to Gal-1 would lead to a decreased amount of protein remaining in solution after removal of the nanoparticles by centrifugation. Therefore, the binding between nanoparticles and cells could be evaluated, both qualitatively and quantitatively, by analyzing the expression of Gal-1 remaining in the solution. As shown in Figure 4, when being mixed with non-conjugated FSNPs, the amount of Gal-1 did not change despite varying concentrations of nanoparticles, suggesting that non-conjugated nanoparticles did not show specific affinity for Gal-1. In contrast, after being mixed with lactose-conjugated FSNPs, the amount of Gal-1 significantly decreased. These results support the binding affinities of lactose-conjugated nanoparticles toward Gal-1. The amount of Gal-1 bound to FSNPs as a function of nanoparticle concentrations was then evaluated by measuring the optical densities of the blots and the subsequent normalizations with control samples. The results, shown in Figure 5, were subsequently fitted to the Langmuir adsorption isotherm given in equation 1 [41]:

| (1) |

in which MGal1 is the mass of Gal-1 bound to FSNPs, Mmax is the maximum mass of Gal-1 (500 ng), KL is a binding constant, and CFSNP is the concentration of FSNPs. The fit of the Langmuir model gave a value of 28 ng/mL−1 for KL.

Figure 4.

Western blots of Gal-1 expression after interaction with nanoparticles.

Figure 5.

Bound Gal-1 to FSNPs as a function of FSNP concentration; (solid line) non-linear regression fit of data using Langmuir adsorption isotherm (eq. 1).

4. Conclusions

In this study, the function of carbohydrate-conjugated nanoparticles as a potential platform for prostate cancer detection was evaluated. The results indicate that carbohydrate-conjugated fluorescent silica nanoparticles exhibited differential binding behavior with prostate cancer cells and normal prostate cells. In particular, the lactose-conjugated FSNPs showed specific binding to PC3 cells that were pre-treated with a reducing agent. These data strongly support our hypothesis that lactose-conjugated nanoparticles could specifically bind to Gal-1, which is over-expressed in prostate cancer cells. Therefore, Gal-1-specific nanoparticles are potentially useful for highly sensitive and selective detection of the prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ARL-ONAMI Center for Nanoarchitectures for Enhanced Performance, and the National Institutes of General Medical Science (NIGMS) under NIH Award Numbers R01GM080295 and 2R15GM066279, for generous financial support.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao XH, Cui YY, Levenson RM, Chung LWK, Nie SM. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salata O. J Nanobiotechnol. 2004;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guarise C, Pasquato L, De Filippis V, Scrimin P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509372103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang CC, Huang YF, Cao ZH, Tan WH, Chang HT. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5735. doi: 10.1021/ac050957q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YJ, Johnson RC, Hupp JT. Nano Lett. 2001;1:165. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu JW, Lu Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otsuka H, Akiyama Y, Nagasaki Y, Kataoka K. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8226. doi: 10.1021/ja010437m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medintz IL, Uyeda HT, Goldman ER, Mattoussi H. Nat Mater. 2005;4:435. doi: 10.1038/nmat1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Schooneveld MM, Vucic E, Koole R, Zhou Y, Stocks J, Cormode DP, Tang CY, Gordon RE, Nicolay K, Meijerink A, Fayad ZA, Mulder WJM. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2517. doi: 10.1021/nl801596a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Wang KM, Santra S, Zhao XJ, Hilliard LR, Smith JE, Wu JR, Tan WH. Anal Chem. 2006;78:646. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santra S, Zhang P, Wang KM, Tapec R, Tan WH. Anal Chem. 2001;73:4988. doi: 10.1021/ac010406+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao XJ, Tapec-Dytioco R, Tan WH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11474. doi: 10.1021/ja0358854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santra S, Yang H, Dutta D, Stanley JT, Holloway PH, Tan WH, Moudgil BM, Mericle RA. Chem Commun. 2004:2810. doi: 10.1039/b411916a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabinovich GA. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1188. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellerhorst J, Troncoso P, Xu XC, Lee J, Lotan R. Urol Res. 1999;27:362. doi: 10.1007/s002400050164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2755. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Ramström O, Yan M. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9082. doi: 10.1021/ac102114z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Ramström O, Yan M. Adv Mater. 2010;22:1946. doi: 10.1002/adma.200903908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caruso F. Adv Mater. 2001;13:11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.de La Fuente JM, Barrientos AG, Rojas TC, Rojo J, Cañada J, Fernández A, Penadés S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernáiz MJ, de la Fuente JM, Barrientos AG, Penadés S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1554. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020503)41:9<1554::aid-anie1554>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang CC, Chen CT, Shiang YC, Lin ZH, Chang HT. Anal Chem. 2009;81:875. doi: 10.1021/ac8010654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YP, Park S, Oh E, Oh YH, Kim HS. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24:1189. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ojeda R, de Paz JL, Barrientos AG, Martin-Lomas M, Penades S. Carbohydr Res. 2007;342:448. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schofield CL, Field RA, Russell DA. Anal Chem. 2007;79:1356. doi: 10.1021/ac061462j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thygesen MB, Sauer J, Jensen KJ. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:1649. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee M, Shin I. Org Lett. 2005;7:4269. doi: 10.1021/ol051753z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhi Z-l, Powell AK, Turnbull JE. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4786. doi: 10.1021/ac060084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seo JH, Adachi K, Lee BK, Kang DG, Kim YK, Kim KR, Lee HY, Kawai T, Cha HJ. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:2197. doi: 10.1021/bc700288z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia BY, Kawar ZS, Ju TZ, Alvarez RA, Sachdev GP, Cummings RD. Nat Methods. 2005;2:845. doi: 10.1038/nmeth808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu LH, Dietsch H, Schurtenberger P, Yan M. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:1349. doi: 10.1021/bc900110x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Liu LH, Ramstrom O, Yan M. Exp Biol Med. 2009;234:1128. doi: 10.3181/0904-MR-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gann JP, Yan M. Langmuir. 2008;24:5319. doi: 10.1021/la7029592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Ramström O, Yan M. Chem Commun. 2011;47:4261. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05299j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stöber W, Fink A, Bohn E. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1968;26:62. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan M, Ren J. Chem Mater. 2004;16:1627. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta D, Cho MJ, Cummings RD, Brewer CF. Biochemistry-us. 1996;35:15236. doi: 10.1021/bi961458+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez-Lucendo MF, Solis D, Andre S, Hirabayashi J, Kasai K, Kaltner H, Gabius HJ, Romero A. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:957. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burnette WN. Anal Biochem. 1981;112:195. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirk JS, Bohn PW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5920. doi: 10.1021/ja030573m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]