Abstract

A significant challenge in oncology is the need to develop in vitro models that accurately mimic the complex microenvironment within and around normal and diseased tissues. Here, we describe a self-folding approach to create curved hydrogel microstructures that more accurately mimic the geometry of ducts and acini within the mammary glands, as compared to existing three-dimensional block-like models or flat dishes. The microstructures are composed of photopatterned bilayers of poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), a hydrogel widely used in tissue engineering. The PEGDA bilayers of dissimilar molecular weights spontaneously curve when released from the underlying substrate due to differential swelling ratios. The photopatterns can be altered via AutoCAD-designed photomasks so that a variety of ductal and acinar mimetic structures can be mass-produced. In addition, by co-polymerizing methacrylated gelatin (methagel) with PEGDA, microstructures with increased cell adherence are synthesized. Biocompatibility and versatility of our approach is highlighted by culturing either SUM159 cells, which were seeded postfabrication, or MDA-MB-231 cells, which were encapsulated in hydrogels; cell viability is verified over 9 and 15 days, respectively. We believe that self-folding processes and associated tubular, curved, and folded constructs like the ones demonstrated here can facilitate the design of more accurate in vitro models for investigating ductal carcinoma.

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed forms of cancer worldwide and ranks second only after lung cancer as a cause of cancer mortality in the United States.1–6 The most predominant type of breast cancer is invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), which makes up about 80% of invasive breast cancer diagnoses.1,5 IDC is a cancer that develops in the milk ducts and then spreads into the fatty tissue of the breast.1 Cancer cells can also metastasize through the lymph system or through blood vessels, spreading to other parts of the body outside the breast.1 To treat breast cancer, a variety of treatment programs that incorporate chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, targeted antibody therapy, radiation, and surgery have been developed, but breast cancer still remains a major health threat.2 Consequently, a deeper understanding of breast cancer biology is needed to improve and create effective treatment methods.

While two-dimensional (2D) cell culture models have provided us with simple and accessible approaches to study cancer cells, the efficacy of these models is limited in that they do not accurately represent important facets of the cellular microenvironment and complex tissue architecture, such as cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions in the three-dimensional (3D) tumor environment.7–11 To address this issue and bridge the gap between 2D cell culture and in vivo models, in vitro 3D models have been proposed and used in cancer cell research to better mimic in vivo structural and biochemical cues. The models include spheroid cultures, liquid overlay cultures, encapsulated cell cultures in gels, microfluidic channel cultures, microfabricated scaffold models, layer by layer cell printed models, microcarrier bead cultures, and stirred or rotary cell cultures.7,12–14 These models have been used to uncover important findings that were not observed with traditional 2D cell culture models, such as the spontaneous assembly of human breast carcinoma cells in suspension and the formations of acini in 3D cell culture in Matrigel®.7,11,15

However, there is still a need to improve these models to more accurately mimic the geometry of the cancerous tumor microenvironment.7,16 More accurate models could improve our understanding of cancer biology and also inform diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, as connections between geometry and cell behavior have been demonstrated in many physiological systems.7,17–21 For example, it has been shown that MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells behave differently than other cells types depending on the curvature of the culture surface and that breast cancer cells can preferentially grow depending on the depth and anisotropy of the culture confinement.17 Many current 3D in vitro models neglect important anatomical aspects of organs, notably 3D micropatterns, layering of cells, and tubular or folded geometries, features that are relevant to anatomic microarchitecture in the human body that consists of highly curved and folded macro- to microstructures (e.g., brain folds, bronchioles, intestines, villi, ducts, and capillaries). These features are particularly important in ductal carcinomas, which originate in tubular ducts.

In this article, we focus on the fabrication and assembly of tubular and curved hydrogel structures. Tubular geometries can significantly affect cell behavior due to strain, curvature, and confinement effects. For example, Jamal et al. noted a significantly higher insulin release from β-TC-6 islet cells cultured in tubular geometries compared with flat geometries.22 Xi et al. discovered that single HeLa cell confinement in varying tubular microstructure could alter cell metaphase plate formation and create chromosomal instabilities not seen in 2D or 3D culture lacking tubular confinement and geometry.23 Nelson et al. demonstrated that the geometry (such as length, concavity, and bifurcation) of tubes could control the local cell environment and thus directly affect branching organ morphogenesis, showing the importance of tubular geometry in the mammary microenvironment.20

Additionally, studies suggest that the lumens in curved or tubular structures can alter the behavior of cancer cells. For example, Bischel et al. observed that kidney epithelial cancer cells were more invasive when cultured with human umbilical vein endothelial cells in lumen structures compared with being cultured in flat 2D or nonlumenal 3D geometries.21 Studies by Nelson et al.,20 Verbridge et al.,24 and Rumpler et al.18 also presented evidence of the importance of lumen structure geometry in cell behavior. Additionally, Bischel et al. were able to create a 3D lumen-based ductal mammary model and found that cell–cell interactions and apico-basal orientation played an important role in recapitulating in vivo-like cell organization in vitro.25

Currently, hollow tubular structures can be fabricated using several methodologies, such as manual rolling,26–28 electrospinning,29 microfluidic approaches,30,31 dip coating,32,33 fluidic self-assembly,34 layer by layer and template leaching,35 electrodeposition,36 molding,37 direct bioprinting,38 and photolithography.39 Involved in many of these approaches is the use of synthetic scaffold materials, such as hydrogels due to their biocompatibility,40 high permeability,41 porosity,42 and structural similarity to the extracellular matrix of tissues.43,44 Self-folding is an emerging morphogenic approach that has been used to create 3D photopatternable hydrogels for drug delivery, tissue engineering, and surgery by the manipulation of strain in layered films.45–47 Advantages that this approach permits include facile layering of multiple cell types, micropatterning, mass-production, high precision reproduction of tube and lumen dimensions and curvature, and material permeability for optical staining and visualization.

We fabricated curved and tubular structures by photopatterning two layers (a bilayer) of hydrogels with different swelling ratios. We encapsulated MDA-MB-231 cells in these curved and tubular poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) bilayer hydrogels to create a platform for cell growth in geometries that mimic mammary acini and ducts. Additionally, we were able to incorporate methacrylated gelatin (methagel) within the PEGDA bilayer hydrogels to enhance cell adhesion and spreading. We verified proliferation of SUM159-green fluorescent protein (GFP) breast cancer cells on the curved outer surface of these cell adhesive tubular structures. Our biofabrication approach is a versatile platform wherein physiologically relevant mammary gland geometries can be mass-produced. Further, as we have shown, multiple cancer cell lines were viable and our approach allows two distinct platforms for cell studies: one in which cells are encapsulated within the interior of the outer gel layer, and another in which cells are deposited and proliferate on the outer surface of the structures. These approaches can be used separately or in concert to create tailored tissue geometries for breast cancer studies.

Materials and Methods

Several of our fabrication methods are adaptations of a previously published protocol.22 The important steps are listed below.

Photomasks

Opaque and transparent 2D photomasks were designed using AutoCAD and were printed on a Mylar film (Fineline, Imaging). These transparency masks were used to fabricate chromium (Cr) masks on glass, which have high fidelity and reproducibility. Briefly, glass slides (2 inches by 2 inches, VWR) were rinsed with acetone, methanol, and isopropyl alcohol, and then dried with a stream of nitrogen gas. SC 1827 (Rohm and Haas) photoresist was spin coated on the clean glass surface at 3000 rpm and baked at 115°C for 1 min. Then, the glass slides were exposed to UV light through the photomasks at ∼160 mJ/cm2 and developed in 351 Developer (Rohm and Haas) in deionized (DI) water (1:5 volume ratio) for 50 s. The patterned glass slides were cleaned using oxygen plasma (Plasma Etch) for 2 min at a radio frequency (RF) power of 100 W and oxygen flow of 20 sccm. Then, 200 nm of Cr was deposited onto the plasma-cleaned glass slides by thermal evaporation, and finally the glass slides were immersed in an acetone bath to dissolve the photoresist.

Chamber for hydrogel photopatterning

Since the hydrogel prepolymer solution had low viscosity and readily flowed, it was necessary to confine it within a chamber with a precise thickness during photopatterning. We fabricated chambers composed of a bottom substrate and side spacers of well-defined thickness. To prepare the bottom substrates of the chamber, we cleaned the glass slides with organic solvents, followed by oxygen plasma cleaning, and thermally evaporated 15 nm of Cr and 100 nm of gold (Au). Cut outs of Reynolds® aluminum foil were used as spacers and were placed in between the top Cr mask and bottom Au substrate. These two substrates were then clamped using binder clips to form a chamber.

Hydrogel prepolymer solution preparation

We utilized two hydrogel prepolymer solutions. One was composed of PEGDA, and the other was a blend of PEGDA and previously reacted methacrylic anhydride and gelatin (referred to as methagel) solution. The solutions were freshly prepared before each experiment and used within a week. Briefly, PEGDA 700 (Sigma Aldrich) and PEGDA 4000 (Monomer Polymer & Dajac Lab) solutions were prepared in separate containers to form 20% (w/v) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Irgacure® 2959 photoinitiator (BASF) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Fisher Scientific) solution (1:1) was added to form 0.5% of the total solution. For experiments where cells were encapsulated in the PEGDA gels, PEGDA 700 final solutions and concentrated PEGDA 4000 solutions were each filter sterilized with 0.22 μm syringe filter before suspension of cells.

We used the following process to create the second prepolymer solution: a blend of PEGDA 4000 and methagel. The methagel solution was synthesized following the procedure described elsewhere.48 Briefly, porcine gelatin powder (Sigma Aldrich) was added to PBS to form a 10% (w/v) solution and heated at 65°C until the gelatin dissolved. Then, methacrylic anhydride (Sigma Aldrich) was added at 0.5% (v/v) and was stir-mixed for ∼2 h at 65°C to form the methagel solution. To create the methagel/PEGDA prepolymer solution, 200 μL methagel solution was added to 1.49 mL of PBS, and then 400 mg of PEGDA 4000 powder and 10 μL of Irgacure 2959 in DMSO (1:1) was added.

Cell culture and GFP transfection

MDA-MB-231 cells (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin streptomycin (PS) or 1% antibiotic antimycotic solution (Mediatech/Corning). SUM159 (generous gift from Dr. S. Ethier, MUSC, SC) were grown in DMEM/F12 50/50 (Mediatech/Corning) supplemented with 5% FBS (Mediatech/Corning), 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone (Sigma Aldrich), and 10 μg/mL insulin (Sigma Aldrich). All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidity controlled incubator with 5% CO2. To create SUM159-GFP cells, GFP-vector and the retroviral packaging vectors were first introduced to 293T cells (ATCC, grown in DMEM with 10% FBS) using lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). The viral supernatant from 293T cells was then collected 48 h after transfection and filtered using a syringe filter. This viral supernatant was then used to infect the SUM159 cells. After 48 h of infection, the viral supernatant was replaced with normal growth media. The GFP-positive SUM159-GFP cells were then selected by cell sorting for GFP by flow cytometry after 3–4 days.

Photoencapsulation of cells in the PEGDA hydrogels

Cells were trypsinized and centrifuged at 1100 rpm to form a pellet. The pellet was resuspended in PBS by pipetting, and then a concentrated PEGDA 4000 solution was added to the suspension. The final solution consisted of 20% PEGDA 4000 and 0.5% photoinitiator solution in PBS. The cell concentration was calculated at this step. To photopattern the cells suspended in the PEGDA 4000 prepolymer solution, the PEGDA 700 solution was first introduced into the space in between the chamber and exposed to UV at ∼150 mJ/cm2, creating the first layer. After photopatterning the first layer, the mixed solution of PEGDA 4000 with suspended cells was dripped onto the bottom substrate of the chamber so that the cell concentration could be uniformly maintained throughout the chamber. After closing the chamber, the solution was exposed to UV light at ∼150 mJ/cm2. The photopatterned cell-laden hydrogels were released from the glass photomask by immersion in either PBS with 1% PS or in cell culture medium. After the structures were released from the substrate, they were transferred to 24 or 48-well plates with each well containing two to three structures. The plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2, and media was changed every 2–3 days.

Cell staining

The cell-encapsulating hydrogels were incubated in solutions containing 2 μM calcein AM and 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1 in PBS for 30–45 min. The structures were then rinsed with PBS several times to wash off remaining dyes before epifluorescence imaging.

Cell seeding on methagel mixed hydrogel

SUM159-GFP cells were grown to a confluence of 70–80%, trypsinized, and then counted using a hemocytometer. The methagel hydrogels were sterilized in 70% ethanol solution for 5 min, washed in PBS, and then transferred to a 24-well plate. To this plate, 5 × 104 SUM159-GFP cells were added per well in a total of 300 μL medium. The plate was kept undisturbed for 2 days until the cells attached firmly onto the outer gel surface. On day 2, hydrogel structures with adhered cells were transferred using a sterile transfer pipette to a new well for further cell culture. The gels were visualized under phase and fluorescent microscopes to image cell growth on the gel and subsequently photographed on days 2, 4, 6, and 9.

Method for cell counting

On each day, six squares of dimensions 0.8 × 0.8 inch (2.032 × 2.032 cm) were cropped from two to three images of different hydrogel bilayer samples, which were seeded with SUM159-GFP-expressing cells on the surface. These cropped images were imported into ImageJ (version 10.2), and an ITCN (Imaged-based tool for counting nuclei) Automatic Nuclei Counter plugin was used to count cells with settings determined specifically for this application. The cell count was averaged for the six cropped images, and the cell number per cm2 was calculated for day 2, 4, 6, and 9.

Statistics

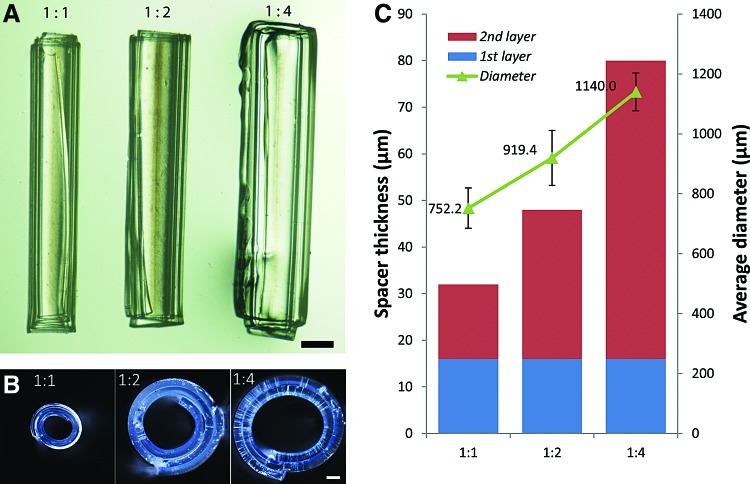

In Figure 2, the green triangles in panel C show the average tube diameter (μm) with standard deviation bars in relation to hydrogel thickness ratio of the first layer to inner layer. The bar graph in Figure 5 shows the average cell density (cells/cm2, averaged from six cropped images) versus days in culture, and standard deviation bars are included.

FIG. 2.

Variation of curvature versus layer thickness. (A) Optical longitudinal and (B) side view of self-folded tubes composed purely of PEGDA formed by Method 1, illustrating that tubes ranging from smaller to larger diameters can be formed by varying the thickness ratio of the two layers from 1:1 to 1:4. Conditions and scale bars are (A) in water, 500 μm and (B) partially dry, 100 μm. (C) Plot of the average outer tube diameter measured in water (μm, green triangles) in relation to the thickness ratio and the average spacer thickness (μm). Blue and red bars correspond to the first (inner) and second (outer) layer thickness, respectively. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

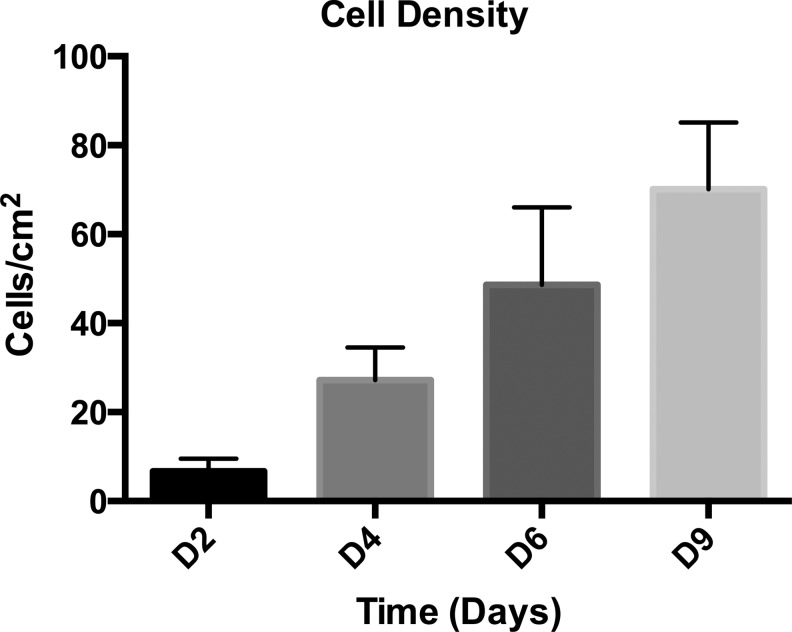

FIG. 5.

Proliferation trend of SUM159-GFP cells cultured on methagel PEGDA. A bar graph of the average cell density versus days in culture (day 2 through day 9), indicating approximately a tenfold increase from D2 through D9. Bars indicate standard deviation.

Microscopy

A Nikon AZ100 multi-zoom microscope with an Intensilight UV lamp and a Nikon DS-Fi1 camera was used for imaging Figures 2, 3, and 6B, C, and D. A Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-E equipped with a Nikon Digital Sight DS-Qi1Mc camera and NIS-Elements AR 3.10 software was used for imaging GFP-positive cell proliferation in Figures 4 and 6E. A Keyence VHX-5000 Digital Microscope was used to image Figure 6B-inset.

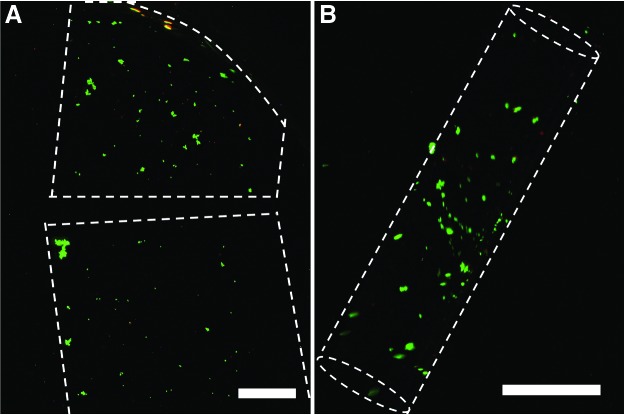

FIG. 3.

Cell culture and viability for photoencapsulated cells. Live/dead assay of MDA-MB-231 cells encapsulated in (A) flat monolayer and (B) curved bilayer hydrogel structures on day 10. Live and dead cells were stained using calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-1, respectively. The live cells appear green and the dead cells appear red. Scale bars are 1 mm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

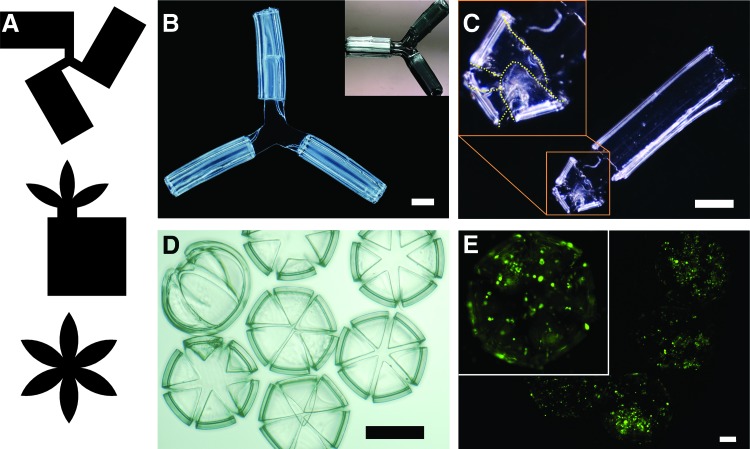

FIG. 6.

Interconnected tubular and acinar mimetic structures. (A) Photomask designs used to pattern and assemble (B) interconnected branched tubes, (C) tubes with lobules, and (D) acinus-mimetic structures. (E) Epifluorescence image of SUM159-GFP cells cultured on methagel PEGDA acinus-mimetic structures showing cell viability. Scale bars are (B, C) 1000 μm, (D) 500 μm, and (E) 200 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

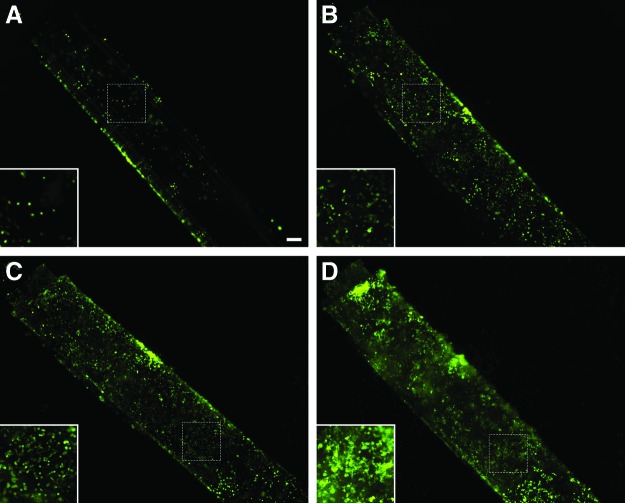

FIG. 4.

Culture and proliferation of SUM159-GFP breast cancer cells on methagel/PEGDA blended self-folded tubes. SUM159-GFP cells were seeded onto the surface of hydrogel blend bilayers with the outer layer made of methagel PEGDA and the inner layer of PEGDA 700. Epifluorescence images of GFP-positive cells (green) were taken over a series of days. (A) By day 2, cells that had attached grew sparsely. (B, C) Cells proliferated and began filling in the empty spaces along the hydrogel surface during day 4 and 6. (D) By day 9, cells were densely populated and the hydrogel tube was overgrown. Scale bar is 200 μm and corresponds to 100 μm in insets. GFP, green fluorescent protein. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Results and Discussion

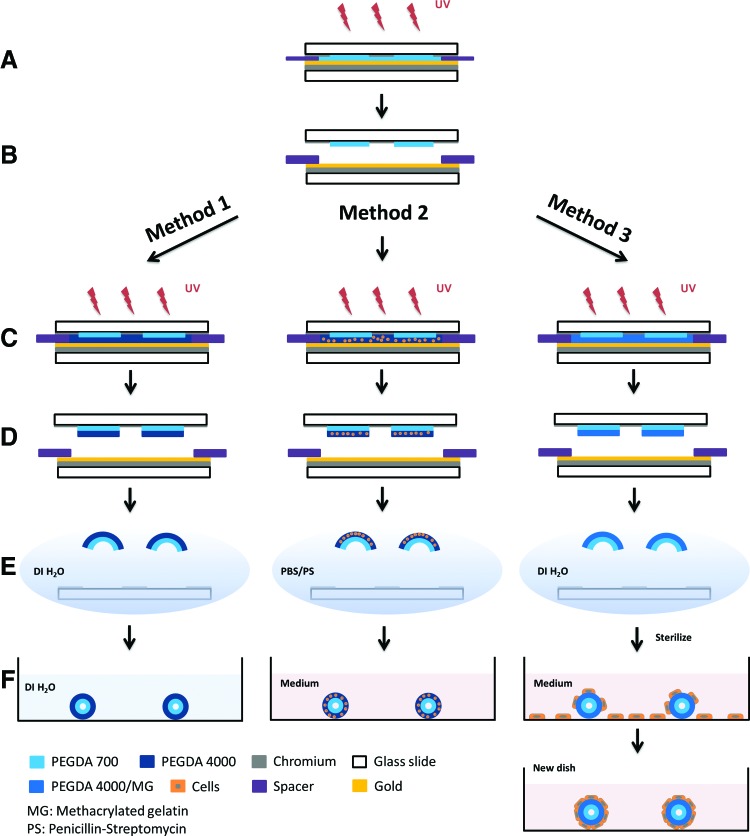

The overall approach for fabricating ductal and acinar mimetic platforms is illustrated in Figure 1. We created the bilayer structures by photocrosslinking a prepolymer solution within a chamber composed of Cr mask and Au bottom substrate (Fig. 1A–D). It is noteworthy that the photopatterning of hydrogels using a UV mask aligner poses several challenges, which are addressed in our fabrication protocol. The photopatterning of a liquid-like low viscosity solution that easily flows is overcome by confining the solution inside a chamber formed using spacers during UV exposure; the chamber also allows control over the thickness. After sequential UV exposure of each of the two PEGDA layers, the developed photocrosslinked bilayers were released from the substrate in aqueous solutions, where the bilayers spontaneously curled up (self-assembled) due to a difference in the swelling ratio of the two layers (Fig. 1E, F).

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the bilayer self-folding procedure. (A–F) General steps involving (A, B) photocrosslinking of the first layer, (C, D) photocrosslinking of the second layer, and (E, F) release and self-folding of the microstructures. The use of these three methods results in pure PEGDA hydrogel structures (Method 1), cell-encapsulated hydrogel structures (Method 2), and cell-adhered hydrogel microstructures (Method 3). PEGDA, poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

Our platform is versatile and amenable to variations in structural design and approaches to cell culture, and can be tailored to specific applications. Method 1 illustrates the process for creating cell-free, self-assembling PEGDA hydrogel bilayers. The structures created by Method 1 were used as controls to optimize the geometry and assembly process, but additional steps were needed to enable cell culture in assembled constructs. In Method 1, pure PEGDA bilayer structures were formed by photocrosslinking PEGDA 700 first, and then PEGDA 4000, and releasing the structures in DI water where they spontaneously assembled (Fig. 1A–F, Method 1).

Methods 2 and 3 show two different approaches of adding cells to the hydrogels by photoencapsulation and adhesion, respectively. One of the key challenges of the latter two methods was keeping the microstructures as sterile as possible during the fabrication and assembly process to prevent contamination during cell growth. Different sterilization approaches were necessary for microstructures formed by Methods 2 and 3. In Method 2, PEGDA solutions were filter sterilized to remove microorganisms before suspending cells, which created a sterile PEGDA-cell mixture that could be subsequently photocrosslinked. After the last UV exposure step (Fig. 1C, Method 2), microstructures were released in 1% PS in PBS in a bio safety cabinet (Fig. 1D, E, Method 2). Although the cell mixture was exposed to ambient air in the clean room during assembly of the chamber, we found that filter sterilization of the solutions and releasing and washing the structures using 1% PS in PBS solution effectively minimized contamination. It is noteworthy that cell viability was not affected by UV exposure over the dose ranges used here.

In Method 3, a prepolymer solution consisting of PEGDA and methagel was used. This prepolymer solution had to be kept at a higher temperature (65°C) to avoid spontaneous gelation and consequently it was challenging to filter sterilize. We note that the method could potentially be modified to incorporate alternate cell adhesive materials such as low melting point gelatin (e.g., fish gelatin) or extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen or laminin. However, since the cells were added after release of the microstructures in this method, it was possible to sterilize with 70% ethanol after assembly (Fig. 1E, Method 3). Ethanol sterilization enabled cell growth on structure surfaces without contamination during the whole course of an experiment. Cell seeding was achieved by introducing a cell solution into a tissue culture plate, which contained assembled microstructures. This resulted in cell attachment to both the fabricated structures and to the tissue culture container (Fig. 1F, Method 3). Subsequent transfer of the cell adhered microstructures to a new plate was necessary to cultivate and image cells that were exclusively attached to the microstructures.

The self-assembly of our hydrogel structures was largely due to the layering of two PEGDA layers of significantly different molecular weights, which resulted in a large difference between the swelling ratios (estimated to be 5.06 and 9.67 for PEGDA 700 and 4000, respectively).22,49 The high swelling ratio for PEGDA 4000 is due to the fact that it has a longer chain length that results in decreased cross-linking during photopatterning and therefore greater absorption of aqueous solutions. Conversely, the higher degree of cross-linking in PEGDA 700 results in lower swelling.50,51 Due to effective adhesion between the two layers, this differential swelling caused the PEGDA 700/4000 bilayers to curve spontaneously. The magnitude of the radius of curvature is a result of the balance between this differential swelling and the bending rigidity of the composite structure—a property that is dependent upon the modulus and thickness of each of the layers. Since swelling ratios and moduli can be predetermined for a prespecified pair of photocrosslinked hydrogels, tubes of different radii can be readily obtained by simply varying the thickness of each of the two hydrogel layers.22 In our experiments with PEGDA, by varying the spacer thickness ratio of the hydrogel's first (inner, 700 MW) layer to the second (outer, 4000 MW) layer during photopatterning between 1:1 to 1:4, the bilayer could be self-assembled into curved tubular structures in a range of diameters, varying from 752.2 to 1140.0 μm on average (Fig. 2). The reported diameters represent the outer measured diameter of the bilayer tubes. The inner diameter can be significantly smaller since the ratio of the lateral dimensions of the bilayer to the radius can cause a multi-rolled structure to form (analogous to a Swiss roll configuration). Depending upon the surface that is used for cell adhesion, either the larger outer diameter or the smaller inner diameter may be relevant. Consequently, we anticipate that this approach could be used to assemble curved hydrogel structures with diameters ranging from hundreds of microns to several millimeters, which is a size range of relevant scale for ducts in mammary glands.52–54

To assess the use of these structures for breast cancer studies, we encapsulated MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells in the second (outer) layer using Method 2. Cells were encapsulated both in flat (control samples, made from a single layer of PEGDA 4000) and curved (folded PEGDA bilayers) structures, and were cultured for a period of 15 days. We observed no significant change of the diameter of the cell encapsulated tubes compared to that of cell-free tubes. To image the encapsulated cells within the hydrogels, the cells were dyed with calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-1. These dyes were able to diffuse through the porous hydrogel network and stain cells. We were able to observe cells and confirm their viability for the extended culture period, as shown in Figure 3. Even though we dripped the cell solution onto the bottom substrate to form a homogeneous cell-hydrogel mixture during fabrication, we observed some clumping of cells in both the flat control and within the self-folded microstructure. Serial mixing and the inclusion of low concentrations of BSA in the medium could modulate this effect.

In addition to encapsulation, cells can also be seeded directly on the surface of the hydrogel microstructures. PEGDA is a diacrylate form of poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG), which is a hydrogel material that is biocompatible, nontoxic, water soluble, and FDA approved for human use.51,55 Due to these favorable properties of PEG, PEGDA is widely used for tissue engineering applications, such as photoencapsulation of cells,56–60 diffusion studies,61,62 and microparticle formation.51 However, this material by itself is universally known to be nonadhesive to cells.51,55,59 Hence, we investigated the use of a cell adhesive gelatin-modified PEGDA material. Gelatin is a biomaterial that contains many cell binding motifs, such as RGD sequences.63 Methacrylate groups can react with the amine groups of gelatin, and this methacrylated gelatin (methagel) can be cross-linked with PEGDA via photopolymerization.64 To test our hypothesis that blending gelatin with PEGDA would improve cell adhesion, cells were plated on flat, single layer hydrogel blends of methagel/PEGDA 4000, or on flat, only PEGDA 4000 controls. We tested three different cell lines: MDA-MB-231, SUM159, and HCC1806. All cell lines adhered and proliferated on the methagel/PEGDA blend surface for 6 days, while cells failed to adhere to the PEGDA controls (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec). This suggested that methagel enhanced cell adhesion to PEGDA. By day 6, SUM159-GFP exhibited more robust adhesion to the blended methagel PEGDA surfaces than MDA-MB-231 or HCC1806. MDA-MB-231 showed the least efficient adhesion to the methagel PEGDA hydrogels, and did not spread well. We explain this result by noting that SUM159-GFP cells exhibit more abundant adhesion molecule expression (including the collagen receptor, alpha2 beta1 integrin) than MDA-MB-231 cells.65–67

Due to the good adhesion of SUM159-GFP cells, we chose these cells for seeding and culture on self-folded methagel PEGDA 4000 bilayer microstructures (Fig. 1, Method 3). The microstructures were formed by combining a methagel PEGDA 4000 blend as the outer layer with pure PEGDA 700 as the inner layer, such that cell adhesion would occur on the outer surface of the bilayer. GFP-labeling facilitated live cell imaging without repeated washing and sample handling. SUM159-GFP cells not only adhered to the curved outer surface, but also exhibited viability up to 9 days (Fig. 4). Cell density was measured using epifluorescence imaging on days 2, 4, 6, and 9, and steady cell growth was noted throughout this time course (Figs. 4 and 5). This increasing cell density denoted a 10-fold proliferation during the course of the experiment and validated the use of the methagel PEGDA polymer in physiologically inspired, biomimetic models with tubular geometries (Fig. 5). We also note that the cell density of each day is statistically different when compared to the cell densities of any of the other days in Figure 5 using the unpaired t-test.

Important features of our microfabrication and assembly process include its versatility, reproducibility, and tunability. AutoCAD design tools make it possible to produce a variety of photomasks with precisely designed uncross-linked and cross-linked regions. Hence, it is possible to create photocrosslinked hydrogel patterns that self-fold into a variety of anatomically inspired structures of relevance to the anatomy and biology of breast cancer. To illustrate these features, we assembled tubes, branched tubes, tubes ending with acinus-like structures, and acinus-like spheres that all mimic geometries seen in situ in mammary glands (Fig. 6).68 The branched structures were designed with three rectangles joined to one area in the center so that the self-folded rectangles stayed connected (Fig. 6A, B). By careful construction and cell seeding, we anticipate that the triple-branched structures could be used to study interactions between three different cell lines that are separately encapsulated in each of these curved structures, or to test the reproducibility of identical experimental conditions. Three flower petal shapes were added to a rectangle to form a structure that would fold into a curved and tubular shape. This created a spherical structure on one end of a tube, mimicking lobules at the ends of mammary ducts (Fig. 6A, C). Flower petal shapes were designed with six petals, so that the petals would fold into spherical structures resembling acini (Fig. 6A, D). Additionally, we seeded SUM159-GFP cells on acinar-mimetic structures made with the methagel PEGDA blend, and verified cell attachment and viability on these models (Fig. 6E).

Conclusion

In summary, our platform offers several advantages for the study of breast cancer cell biology and responses to therapy. First, due to the anatomical microstructure in mammary gland ducts, we believe that tubular and curved hydrogel structures are more accurate models for ducts and acini compared with either 2D culture or gel block models. The breast duct is a curved and tubular structure with layers of ductal epithelium, myoepithelium, and basement membrane.69 Our hydrogel structures, with distinct layered regions for potentially separated populations of cells in culture, can advance the coculture of multiple cell lines in one hydrogel system that has biologically inspired, curved geometries. Second as shown here, cells can be grown in two types of modalities: encapsulated (in PEGDA) or surface-adhered (with the incorporation of methagel to seed cells on the surface), seeded at controlled concentrations, and kept viable for long time periods. Third, the porosity of the hydrogels allows efficient access of oxygen, nutrients, chemotherapeutics, and labeling reagents to encapsulated cells. Oxygen and nutrients during cell culture and staining agents can easily diffuse through the polymer network and reach cells. Finally, the optically transparent constructs facilitate imaging, in contrast to other systems that are currently in use.22 In this study, we demonstrated a new approach to culture breast cancer cells in and on curved bilayer hydrogel structures that were inspired by breast duct geometry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award Numbers U54CA141868, NRSA F31 EB018187, and the National Science Foundation Grant number CBET-1462184. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Breast Cancer. American Cancer Society 2014. Retrieved from www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003090-pdf.pdf; Last accessed on March2, 2016

- 2.The Breast Cancer Landscape. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program 2016. Retreived from http://cdmrp.army.mil/bcrp/pdfs/bc_landscape.pdf; Last accessed March2, 2016

- 3.World Health Organization/International Agency for Research on Cancer. Latest world cancer statistics—global cancer burden rises to 14.1 million new cases in 2012: marked increase in breast cancers must be addressed. World Health Organization Press Release N° 223, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., and Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA: a cancer J Clin 65, 5, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bombonati A., and Sgroi D.C. The molecular pathology of breast cancer progression. J Pathol 223, 307, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C., Tang Z., Zhao Y., Yao R., Li L., and Sun W. Three-dimensional in vitro cancer models: a short review. Biofabrication 6, 022001, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pampaloni F., Reynaud E.G., and Stelzer E.H. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8, 839, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker B.M., and Chen C.S. Deconstructing the third dimension: how 3D culture microenvironments alter cellular cues. J Cell Sci 125, 3015, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tibbitt M.W., and Anseth K.S. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol Bioeng 103, 655, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asghar W., El Assal R., Shafiee H., Pitteri S., Paulmurugan R., and Demirci U. Engineering cancer microenvironments for in vitro 3-D tumor models. Mater Today 18, 539, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickman J.A., Graeser R., de Hoogt R., Vidic S., Brito C., Gutekunst M., van der Kuip H., and Consortium I.P. Three-dimensional models of cancer for pharmacology and cancer cell biology: capturing tumor complexity in vitro/ex vivo. Biotechnol J 9, 1115, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J.B., Stein R., and O'Hare M.J. Three-dimensional in vitro tissue culture models of breast cancer—a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 85, 281, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J.B. Three-dimensional tissue culture models in cancer biology. Semin Cancer Biol 15, 365, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debnath J., Muthuswamy S.K., and Brugge J.S. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods 30, 256, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weigelt B., Ghajar C.M., and Bissell M.J. The need for complex 3D culture models to unravel novel pathways and identify accurate biomarkers in breast cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 69–70, 42, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikkhah M., Strobl J.S., and Agah M. Attachment and response of human fibroblast and breast cancer cells to three dimensional silicon microstructures of different geometries. Biomed Microdevices 11, 429, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rumpler M., Woesz A., Dunlop J.W., van Dongen J.T., and Fratzl P. The effect of geometry on three-dimensional tissue growth. J R Soc Interface 5, 1173, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serbo J.V., Kuo S., Lewis S., Lehmann M., Li J., Gracias D.H., and Romer L.H. Patterning of fibroblast and matrix anisotropy within 3d confinement is driven by the cytoskeleton. Adv Healthc Mater 5, 146, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson C.M., Vanduijn M.M., Inman J.L., Fletcher D.A., and Bissell M.J. Tissue geometry determines sites of mammary branching morphogenesis in organotypic cultures. Science 314, 298, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bischel L.L., Sung K.E., Jimenez-Torres J.A., Mader B., Keely P.J., and Beebe D.J. The importance of being a lumen. FASEB J 28, 4583, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamal M., Kadam S.S., Xiao R., Jivan F., Onn T.M., Fernandes R., Nguyen T.D., and Gracias D.H. Bio-origami hydrogel scaffolds composed of photocrosslinked PEG bilayers. Adv Healthc Mater 2, 1142, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xi W., Schmidt C.K., Sanchez S., Gracias D.H., Carazo-Salas R.E., Jackson S.P., and Schmidt O.G. Rolled-up functionalized nanomembranes as three-dimensional cavities for single cell studies. Nano Lett 14, 4197, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verbridge S.S., Chakrabarti A., DelNero P., Kwee B., Varner J.D., Stroock A.D., and Fischbach C. Physicochemical regulation of endothelial sprouting in a 3D microfluidic angiogenesis model. J Biomed Mater Res A 101, 2948, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bischel L.L., Beebe D.J., and Sung K.E. Microfluidic model of ductal carcinoma in situ with 3D, organotypic structure. BMC Cancer 15, 12, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seunarine K., Meredith D.O., Riehle M.O., Wilkinson C.D.W., and Gadegaard N. Biodegradable polymer tubes with lithographically controlled 3D micro- and nanotopography. Microelectron Eng 85, 1350, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papenburg B.J., Liu J., Higuera G.A., Barradas A.M., de Boer J., van Blitterswijk C.A., Wessling M., and Stamatialis D. Development and analysis of multi-layer scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 30, 6228, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng M., Kumbar S.G., Nair L.S., Weikel A.L., Allcock H.R., and Laurencin C.T. Biomimetic structures: biological implications of dipeptide-substituted polyphosphazene-polyester blend nanofiber matrices for load-bearing bone regeneration. Adv Funct Mater 21, 2641, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shih Y.H., Yang J.C., Li S.H., Yang W.C.V., and Chen C.C. Bio-electrospinning of poly(l-lactic acid) hollow fibrous membrane. Text Res J 82, 602, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.He X.H., Wang W., Deng K., Xie R., Ju X.J., Liu Z., and Chu L.Y. Microfluidic fabrication of chitosan microfibers with controllable internals from tubular to peapod-like structures. RSC Adv 5, 928, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh J., Kim K., Won S.W., Cha C., Gaharwar A.K., Selimovic S., Bae H., Lee K.H., Lee D.H., Lee S.H., and Khademhosseini A. Microfluidic fabrication of cell adhesive chitosan microtubes. Biomed Microdevices 15, 465, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Y., Kamphuis M.M., Zhang Z., Sterk L.M., Vermes I., Poot A.A., Feijen J., and Grijpma D.W. Flexible and elastic porous poly(trimethylene carbonate) structures for use in vascular tissue engineering. Acta Biomater 6, 1269, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma X.H., Xu Z.L., Wu F., and Xu H.T. PFSA-TiO2(or Al2O3)-PVA/PVA/PAN difunctional hollow fiber composite membranes prepared by dip-coating method. Iran Polym J 21, 31, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yue T., Nakajima M., Takeuchi M., Hu C., Huang Q., and Fukuda T. On-chip self-assembly of cell embedded microstructures to vascular-like microtubes. Lab Chip 14, 1151, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva J.M., Duarte A.R., Custodio C.A., Sher P., Neto A.I., Pinho A.C., Fonseca J., Reis R.L., and Mano J.F. Nanostructured hollow tubes based on chitosan and alginate multilayers. Adv Healthc Mater 3, 433, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozawa F., Ino K., Takahashi Y., Shiku H., and Matsue T. Electrodeposition of alginate gels for construction of vascular-like structures. J Biosci Bioeng 115, 459, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soletti L., Hong Y., Guan J., Stankus J.J., El-Kurdi M.S., Wagner W.R., and Vorp D.A. A bilayered elastomeric scaffold for tissue engineering of small diameter vascular grafts. Acta Biomater 6, 110, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y., Yu Y., and Ozbolat I.T. Direct bioprinting of vessel-like tubular microfluidic channels. J Nanotechnol Eng Med 4, 020902, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arayanarakool R., Meyer A.K., Helbig L., Sanchez S., and Schmidt O.G. Tailoring three-dimensional architectures by rolled-up nanotechnology for mimicking microvasculatures. Lab Chip 15, 2981, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu J., and Marchant R.E. Design properties of hydrogel tissue-engineering scaffolds. Expert Rev Med Devices 8, 607, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen K.T., and West J.L. Photopolymerizable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 23, 4307, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Annabi N., Nichol J.W., Zhong X., Ji C., Koshy S., Khademhosseini A., and Dehghani F. Controlling the porosity and microarchitecture of hydrogels for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 16, 371, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drury J.L., and Mooney D.J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials 24, 4337, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serbo J.V., and Gerecht S. Vascular tissue engineering: biodegradable scaffold platforms to promote angiogenesis. Stem Cell Res Ther 4, 8, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malachowski K., Breger J., Kwag H.R., Wang M.O., Fisher J.P., Selaru F.M., and Gracias D.H. Stimuli-responsive theragrippers for chemomechanical controlled release. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 53, 8045, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zakharchenko S., Sperling E., and Ionov L. Fully biodegradable self-rolled polymer tubes: a candidate for tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomacromolecules 12, 2211, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Breger J.C., Yoon C., Xiao R., Kwag H.R., Wang M.O., Fisher J.P., Nguyen T.D., and Gracias D.H. Self-folding thermo-magnetically responsive soft microgrippers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 7, 3398, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bassik N., Brafman A., Zarafshar A.M., Jamal M., Luvsanjav D., Selaru F.M., and Gracias D.H. Enzymatically triggered actuation of miniaturized tools. J Am Chem Soc 132, 16314, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baek K., Jeong J.H., Shkumatov A., Bashir R., and Kong H. In situ self-folding assembly of a multi-walled hydrogel tube for uniaxial sustained molecular release. Adv Mater 25, 5568, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao C., Lin Z., Yin H., Ma Y., Xu F., and Yang W. PEG molecular net-cloth grafted on polymeric substrates and its bio-merits. Sci Rep 4, 4982, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le Goff G.C., Srinivas R.L., Hill W.A., and Doyle P.S. Hydrogel microparticles for biosensing. Eur Polym J 72, 386, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rusby J., Brachtel E., Michaelson J., Koerner F., and Smith B. Breast duct anatomy in the human nipple: three-dimensional patterns and clinical implications. Breast Cancer Res Treat 106, 171, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramsay D.T., Kent J.C., Owens R.A., and Hartmann P.E. Ultrasound imaging of milk ejection in the breast of lactating women. Pediatrics 113, 361, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramsay D.T., Kent J.C., Hartmann R.A., and Hartman P.E. Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. J Anat 206, 525, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nemir S., Hayenga H.N., and West J.L. PEGDA hydrogels with patterned elasticity: novel tools for the study of cell response to substrate rigidity. Biotechnol Bioeng 105, 636, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hwang N.S., Varghese S., Zhang Z., and Elisseeff J. Chondrogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cells in arginine-glycine-aspartate-modified hydrogels. Tissue Eng 12, 2695, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albrecht D.R., Tsang V.L., Sah R.L., and Bhatia S.N. Photo- and electropatterning of hydrogel-encapsulated living cell arrays. Lab Chip 5, 111, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Panda P., Ali S., Lo E., Chung B.G., Hatton T.A., Khademhosseini A., and Doyle P.S. Stop-flow lithography to generate cell-laden microgel particles. Lab Chip 8, 1056, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ali S., Saik J.E., Gould D.J., Dickinson M.E., and West J.L. Immobilization of cell-adhesive laminin peptides in degradable PEGDA hydrogels influences endothelial cell tubulogenesis. Biores Open Access 2, 241, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Munoz-Pinto D.J., Jimenez-Vergara A.C., Gharat T.P., and Hahn M.S. Characterization of sequential collagen-poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate interpenetrating networks and initial assessment of their potential for vascular tissue engineering. Biomaterials 40, 32, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bader R.A., Herzog K.T., and Kao W.J. A study of diffusion in poly(ethyleneglycol)-gelatin based semi-interpenetrating networks for use in wound healing. Polym Bull (Berl) 62, 381, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cuchiara M.P., Allen A.C., Chen T.M., Miller J.S., and West J.L. Multilayer microfluidic PEGDA hydrogels. Biomaterials 31, 5491, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grover C.N., Gwynne J.H., Pugh N., Hamaia S., Farndale R.W., Best S.M., and Cameron R.E. Crosslinking and composition influence the surface properties, mechanical stiffness and cell reactivity of collagen-based films. Acta Biomater 8, 3080, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nichol J.W., Koshy S.T., Bae H., Hwang C.M., Yamanlar S., and Khademhosseini A. Cell-laden microengineered gelatin methacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials 31, 5536, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pan H., Wanami L.S., Dissanayake T.R., and Bachelder R.E. Autocrine semaphorin3A stimulates alpha2 beta1 integrin expression/function in breast tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 118, 197, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neve R.M., Chin K., Fridlyand J., Yeh J., Baehner F.L., Fevr T., Clark L., Bayani N., Coppe J.P., Tong F., Speed T., Spellman P.T., DeVries S., Lapuk A., Wang N.J., Kuo W.L., Stilwell J.L., Pinkel D., Albertson D.G., Waldman F.M., McCormick F., Dickson R.B., Johnson M.D., Lippman M., Ethier S., Gazdar A., and Gray J.W. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell 10, 515, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Comparison of All Genes in Neve CellLine Oncomine Research Edition. www.oncomine.org

- 68.Schnitt S.J., and Collins L.C. Biopsy Interpretation of the Breast. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kalluri R., and Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 392, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.