Abstract

Objectives: To determine whether acupuncture use, sociodemographic characteristics, and existing health conditions differ between acupuncture-preferred consumers (i.e., those who deem acupuncture to be one of the three most important complementary and alternative medicine [CAM] modalities used) and non–acupuncture-preferred consumers who used acupuncture in the past 12 months

Methods: This is a secondary analysis of the National Health Interview Survey Sample Adult File and Adult Alternative Medicine datasets collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during 2012. The sample was drawn from the noninstitutionalized civilian population of the United States. The datasets yielded 34,525 respondents aged 18 years and older. Measures included in the analysis were acupuncture use in the past 12 months, sociodemographic characteristics, and existing health conditions. Analyses were performed by using Stata software, version 9.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results: Of the 10,158 adults who responded to the question regarding the “three most important” CAM modalities used, 572 (5.6%) had used acupuncture in the past 12 months. Of these, 456 (79.7%) chose acupuncture as one of the top three CAM modalities most important to their health. Acupuncture-preferred consumers reported significantly more visits to acupuncturists (7.46 versus 3.99 visits; p < 0.001), as well as higher out-of-pocket costs ($342.8 versus $246.4; p < 0.001), compared with non–acupuncture-preferred consumers. The logistic regression model revealed that with every additional CAM modality used, the likelihood of deeming acupuncture as one of the three CAM modalities most important to one's health decreased by 39% (odds ratio, 0.61; 95% confidence interval, 0.52–0.71; p < 0.001). Health conditions were not statistically significant predictors.

Conclusions: A consumer's preference for acupuncture appeared not to be driven by health conditions but rather was related to sociodemographic factors. This suggests that health education regarding acupuncture may need to be tailored to certain consumer groups, such as those residing in the South, and could provide more information on the comparative effectiveness of acupuncture for various health conditions.

Introduction

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the U.S. adult population increased substantially in the 1990s1 and has remained at a relatively stable rate (36%–38%) over the past 10 years.2–4 Acupuncture is one CAM therapy that has gained increasing popularity with the U.S. public since it was introduced to the United States in the 1970s,5 and rightfully so given the good evidence that acupuncture is safe and effective,6 particularly in pain management.7,8 According to U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data, approximately 8.2 million (4.2%) U.S. adults in 2002 and 14.01 million (6.3%) in 2007 had ever used acupuncture.2,3,9 This equated to 79.2 visits to acupuncturists per 1000 U.S. adults in 2007, a nearly three-fold increase from the 27.2 visits per 1000 adults reported in 1997.10 Acupuncture is also comparatively popular elsewhere,11,12 with approximately 9% of Australians surveyed in 2005 reporting acupuncture use13 and approximately 3.9 million acupuncture treatments delivered in the United Kingdom in 2009.14

The literature identifies many factors that may be positively related to acupuncture use, including Asian descent, female sex, living in the western part of the United States, poor self-reported health status, and high education level.15,16 Certain health conditions are also more likely to be treated by acupuncture, such as musculoskeletal pain disorders15,17,18 and, to a lesser extent, women's health conditions and cancer care.19,20

Consumer beliefs also contribute to the use of acupuncture. For example, some patients are attracted to acupuncture as a complementary/alternative form of treatment that is perceived as very different from biomedicine, intuiting that it might help their particular symptoms; others may seek acupuncture as just one more thing to try in a long history of unsuccessful treatments.21,22 Qualitative studies suggest that acupuncture patients value several aspects of acupuncture, including the effects it has on their symptoms and broader well-being, the holistic nature of the treatment, and the collaborative therapeutic relationship with the acupuncturist.23–26 Despite these insights into the acupuncture consumer, little is known about the fundamental demographic or clinical differences between consumers who value acupuncture and those who do not.

To address these aforementioned knowledge gaps, this study examined whether acupuncture use, sociodemographic characteristics, and existing health conditions differ between acupuncture-preferred consumers (i.e., those who deem acupuncture to be one of the three most important CAM modalities used) and non–acupuncture-preferred consumers among those who used acupuncture in the past 12 months. The hypothesis was that the characteristics of acupuncture-preferred consumers will be different from those of non–acupuncture-preferred consumers, based on previous reports associating acupuncture use with ethnicity, education, and region of residence.16,17 Another hypothesis was that pain-related conditions will be more prevalent among acupuncture-preferred consumers given that these conditions are the most common reason for visiting an acupuncturist.12,27

Materials and Methods

Data sources and sample

This study was a secondary analysis of data from the 2012 NHIS, a cross-sectional household interview survey targeting the noninstitutionalized civilian population of the United States conducted periodically by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS has collected detailed data on CAM use every 5 years since 2002. The current analysis used the 2012 Sample Adult File and Adult Alternative Medicine data subsets published online by the CDC. The Sample Adult File contained information on the participant's sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and specific health conditions, while the Adult Alternative Medicine supplement comprised information on CAM use. The total household response rate for the 2012 NHIS was 77.6%. The interviewed sample consisted of 42,366 eligible households, which yielded 34,525 respondents aged 18 years and older. Further details of the NHIS sample are reported elsewhere.28

In the 2012 NHIS Adult Alternative Medicine supplement, respondents were asked, During the past 12 months, which 3 of the listed 18 nonconventional healthcare practices* were the most important to their health? If acupuncture was selected as one of the top three modalities, it was deemed one of the three CAM modalities most important to the respondent's health. The current study used the subset sample of recent acupuncture users (i.e., the respondents who reported using acupuncture in the past 12 months [n = 572]). Of these respondents, those who considered acupuncture to be one of the top three CAM modalities most important to their health were defined as acupuncture-preferred consumers (n = 456), and those who did not deem acupuncture to be one of the top three CAM modalities were defined as non–acupuncture- preferred consumers (n = 116).

Measures

Data collected on acupuncture use in the past 12 months included number of visits, estimated out-of-pocket cost in U.S. dollars, and whether health insurance covered some or all costs.

Sociodemographic items included sex (male and female), age (in years), race/ethnicity (Hispanic-white, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic other), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduates and/or with some certified degree after high school, bachelor degree, master degree and higher), marital status (currently married or living together but not married), and region of residence in United States (Northeast, Northcentral/Midwest, South, and West).

In relation to health conditions, respondents were asked whether in the past 12 months they had experienced any episodes of recurring headache, abdominal pain, severe strains/sprains, dental pain, other muscle/bone pain, other chronic pain, respiratory allergy, digestive allergy, eczema/skin allergy, other allergies, skin problems other than eczema/allergies, problems with acid reflux/heartburn, fever for more than 1 day, a head/chest cold, nausea/vomiting, sore throat, infectious disease/problems with immune system, memory or other cognitive function loss, neurologic problems, excessive use of alcohol/tobacco, substance abuse, problems with being overweight, fatigue/lack of energy for more than 3 days, excessive sleepiness during the day, insomnia/trouble sleeping, frequently feeling anxious/nervous/worried, and feeling stressed.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed by using Stata software, version 9.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). All analyses used the NHIS Sample Adult Weight–Final Annual, including design, ratio, nonresponse, and post-stratification adjustments for sample adults.28 Stata survey commands were used for the complex survey sample design. Overall analysis included examination of the weighted comparison (chi-square and independent t test or nonparametric median test) between acupuncture-preferred consumers and non–acupuncture-preferred consumers in terms of their sociodemographic profile and existing health conditions. Variables with a significance level less than 0.15 were entered into weighted logistic regression to determine which sociodemographic or health condition variables were significantly associated with acupuncture preference. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Of the 10,158 adults who responded to the “three most important” CAM therapy questions, 572 (5.6%) had used acupuncture in the past 12 months. Of these, 456 (79.7%) chose acupuncture as one of the top three CAM modalities most important to their health, and 116 (20.3%) did not make the same choice. Bivariate tests revealed several statistically significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics between the acupuncture-preferred consumers and non–acupuncture-preferred consumers (p < 0.01) (Table 1). Acupuncture-preferred consumers were more likely to be male (33.2% versus 18.1%; p = 0.006), reside in the Northeast United States (21.6% versus 5.0%; p < 0.001), and use fewer CAM modalities (3.02 versus 5.86; p < 0.001) compared with non–acupuncture-preferred consumers. Education, income, marital status, and spending on medical care did not significantly differ between groups.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Level of Acupuncture Use of Acupuncture-Preferred Consumers and Non–Acupuncture-Preferred Consumers in Past 12 Months (n = 572)

| Variable | Acupuncture-preferred (n = 456) | Non–acupuncture-preferred (n = 116) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Agea | 49.8 (47.8–51.8) | 48.7 (45.8–51.6) | 0.54 |

| Sex | 0.006 | ||

| Male | 33.2 | 18.1 | |

| Female | 66.8 | 81.9 | |

| Region of United States | <0.001 | ||

| Northeast | 21.6 | 5.0 | |

| Midwest | 13.8 | 32.9 | |

| South | 20.7 | 13.2 | |

| West | 43.9 | 48.9 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.097 | ||

| Hispanic | 11.6 | 11.3 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 70.4 | 76.2 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5.3 | 8.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 12.4 | 3.2 | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 0.3 | 0.6 | |

| Education | 0.145 | ||

| Less than high school | 7.3 | 1.1 | |

| High school graduate and some degree | 42.4 | 4.3 | |

| Bachelor degree | 29.0 | 29.0 | |

| Master degree and higher | 21.3 | 26.4 | |

| Personal earning in the past year (US$) | 0.338 | ||

| <$10,000 | 6.3 | 9.7 | |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 8.8 | 5.8 | |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 8.3 | 13.4 | |

| $35,000–$54,999 | 14.6 | 10.1 | |

| $55,000–$74,999 | 8.9 | 6.6 | |

| ≥$75,000 | 15.3 | 20.3 | |

| Refused to report or don't know | 9.2 | 13.4 | |

| Not worked in the past year | 28.6 | 20.8 | |

| Marital status/relationship | 0.105 | ||

| Married or living with a partner | 63.5 | 48.8 | |

| Divorced or separated | 13.3 | 20.1 | |

| Widowed | 5.9 | 7.2 | |

| Never married | 17.3 | 23.9 | |

| Family spending on medical care | 0.587 | ||

| $0 | 6.1 | 1.8 | |

| $1–$499 | 25.6 | 22.9 | |

| $500–$1999 | 33.7 | 37.5 | |

| $2000–$2999 | 11.2 | 13.8 | |

| $3000–$4999 | 9.8 | 7.9 | |

| ≥$5000 | 1.4 | 16.1 | |

| Total no. of CAM modalities useda | 3.02 (2.78–3.25) | 5.86 (5.40–6.32) | <0.001 |

| Acupuncture use | |||

| No. of visits to acupuncturista | 7.47 (6.24–8.70) | 3.99 (3.05–4.93) | <0.001 |

| Out-of-pocket for acupuncture expense (US$)a | 342.8 (284.1–401.6) | 246.4 (168.8–324.1) | <0.001 |

| Insurance covered the acupuncture expense | 0.189 | ||

| Covered by insurance (some or all) | 25.7 | 17.8 | |

| Not covered by insurance | 74.3 | 82.2 | |

Mean and 95% confidence interval presented in the table.

CAM, complementary and alternative medicine.

Acupuncture use

Acupuncture-preferred consumers reported significantly more visits to acupuncturists (7.46 versus 3.99 visits; p < 0.001) as well as higher out-of-pocket costs ($342.8 versus $246.4; p < 0.001) in the past 12 months than non–acupuncture-preferred consumers. Health insurance coverage did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 1).

Health conditions

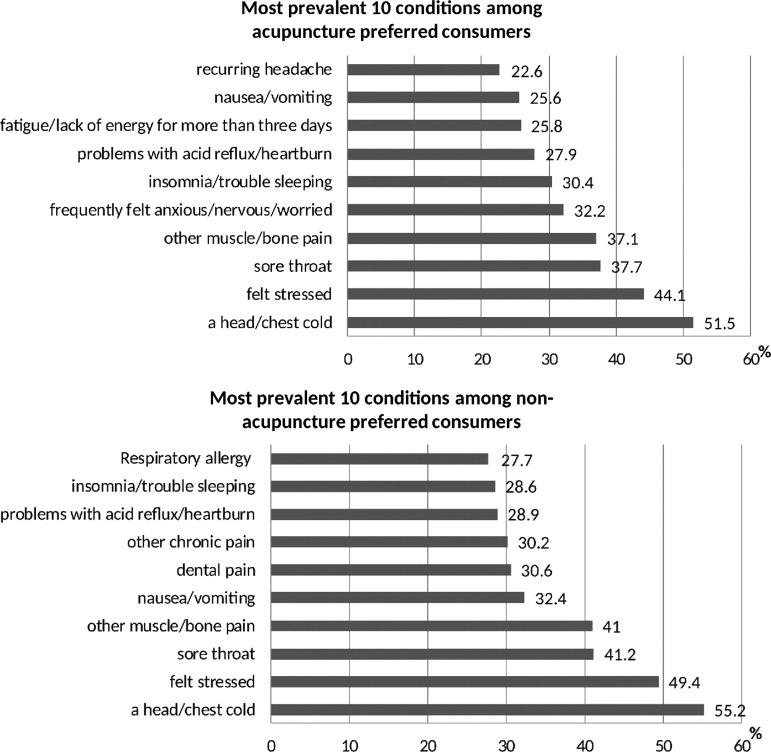

Health condition prevalence did not vary significantly between acupuncture-preferred consumers and non–acupuncture-preferred consumers, with the exception of dental pain, for which there was a statistically significantly higher prevalence among non–acupuncture-preferred consumers (p = 0.017) (Table 2). Figure 1 illustrates the differences in the top 10 existing health conditions reported by acupuncture-preferred consumers and non–acupuncture-preferred consumers in the past 12 months. Of the top 10 conditions reported, the 4 most prevalent conditions (head/chest cold, having felt stressed, sore throat, and other muscle/bone pain) were identical across both groups. Stress-related symptoms, such as frequently felt anxious, trouble sleeping, fatigue, and recurring headache, were more prevalent among acupuncture-preferred consumers.

Table 2.

Comparison of Existing Health Conditions of Acupuncture-Preferred Consumers and Non–Acupuncture-Preferred Consumers in Past 12 Months (n = 572)

| Variable | Acupuncture-preferred (n = 456) (%) | Non–acupuncture-preferred (n = 116) (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain-related conditions | |||

| Recurring headache | 22.6 | 27.0 | 0.444 |

| Abdominal pain | 16.8 | 20.9 | 0.443 |

| Any severe strains/sprains | 11.8 | 11.3 | 0.887 |

| Dental pain | 17.7 | 30.6 | 0.017 |

| Other muscle/bone pain | 37.1 | 41.0 | 0.539 |

| Other chronic pain | 22.4 | 30.2 | 0.159 |

| Non–pain-related conditions | |||

| Respiratory allergy | 19.5 | 27.7 | 0.302 |

| Digestive allergy | 9.8 | 16.3 | 0.110 |

| Eczema/skin allergy | 13.3 | 19.9 | 0.268 |

| Other allergies | 6.2 | 6.4 | 0.947 |

| Skin problems other than eczema/allergies | 10.5 | 19.1 | 0.043 |

| Problems with acid reflux/heartburn | 27.9 | 28.9 | 0.882 |

| Fever for >1 d | 17.5 | 16.8 | 0.889 |

| Head/chest cold | 51.5 | 55.2 | 0.561 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 25.6 | 32.4 | 0.252 |

| Sore throat | 37.7 | 41.2 | 0.064 |

| Infectious disease/problems with immune system | 7.9 | 9.2 | 0.603 |

| Memory or other cognitive function loss | 7.3 | 8.3 | 0.794 |

| Neurologic problems | 9.2 | 12.5 | 0.429 |

| Excessive use of alcohol/tobacco | 8.0 | 8.0 | 0.997 |

| Substance abuse | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.616 |

| Problems with being overweight | 17.6 | 19.1 | 0.730 |

| Fatigue/lack of energy for >3 d | 25.8 | 25.2 | 0.902 |

| Excessive sleepiness during the day | 20.5 | 16.1 | 0.347 |

| Insomnia/trouble sleeping | 30.4 | 28.6 | 0.758 |

| Frequently felt anxious/nervous/worried | 32.2 | 25.0 | 0.187 |

| Felt stressed | 44.1 | 49.4 | 0.415 |

FIG. 1.

The most prevalent 10 conditions reported among acupuncture-preferred consumers and non–acupuncture-preferred consumers in the past 12 months (n = 572).

Predictors of acupuncture preference

The logistic regression model (Table 3) revealed that the number of CAM modalities used was the main predictor of acupuncture preference. With every additional CAM modality used, the likelihood of including acupuncture as one of the top three CAM modalities most important to a participant's health decreased by 39% (odds ratio [OR], 0.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52–0.71; p < 0.001). Compared with recent acupuncture users residing in the Northeast United States, those who resided in Midwest (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.06–0.40; p < 0.001) and West (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.18–0.80; p = 0.011) were much less likely to select acupuncture as one of the three CAM modalities most important to their health. While non-Hispanic white and Asian participants were more likely to prefer the use of acupuncture than were Hispanics, the difference between ethnicities was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Similarly, education level and marital status were not significantly related to acupuncture preference. None of the health conditions included in the logistic model were statistically significant.

Table 3.

Potential Factors Related to Acupuncture Preference (Reference, Not Preferred Acupuncture) (n = 566)

| Factors | Reference | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of CAM modalities used | 0.61 (0.52–0.71) | <0.001 | |

| Women | Men | 0.66 (0.32–1.36) | 0.266 |

| Region of United States | Northeast | ||

| Midwest | 0.16 (0.06–0.40) | <0.001 | |

| South | 0.57 (0.21–1.53) | 0.266 | |

| West | 0.38 (0.18–0.80) | 0.011 | |

| Race/ethnicity | Hispanic | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.25 (0.62–2.53) | 0.532 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.60 (0.22–1.59) | 0.303 | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.79 (0.42–7.73) | 0.432 | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 0.42 (0.47–3.77) | 0.437 | |

| Education | High school graduate or lessa | ||

| Bachelor degree | 1.29 (0.62–2.70) | 0.740 | |

| Master degree and higher | 0.85 (0.35–2.04) | 0.716 | |

| Marital status/relationship | Married or living with a partner | ||

| Divorced or separated | 0.86 (0.37–1.99) | 0.720 | |

| Widowed | 0.53 (0.20–1.38) | 0.192 | |

| Never married | 0.82 (0.39–1.67) | 0.175 | |

| Dental pain | No dental pain | 0.53 (0.25–1.13) | 0.100 |

| Digestive allergy | No digestive allergy | 1.29 (0.48–3.48) | 0.605 |

| Skin problems other than eczema/allergies | No skin problems | 0.64 (0.30–1.36) | 0.248 |

| Sore throat | No sore throat | 0.90 (0.65–1.25) | 0.546 |

Because of the limited number of participants in the less than high school education group, participants in this group were combined with the high school graduate group as the reference to logistic regression.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of 2012 NIHS data is the first known study to examine the differences between acupuncture-preferred consumers and non–acupuncture-preferred consumers in terms of acupuncture use, sociodemographic characteristics, and existing health conditions. The study revealed that close to 80% of the recent acupuncture users were acupuncture-preferred consumers. Compared with their counterparts, acupuncture-preferred consumers visited acupuncturists more frequently, spent more out of pocket on acupuncture, used fewer CAM modalities, and were more likely to be residing in the Northeast United States. The implications of these key findings are discussed below.

It was not surprising that acupuncture-preferred consumers had consulted acupuncturists more frequently and had spent more out of pocket on acupuncture. Given that most (80%) recent acupuncture use was reported among acupuncture-preferred consumers, the finding suggests that consumers were loyal to this CAM modality and may indicate that consumers who prefer acupuncture may find it helpful as a long-term therapy and thus continue to invest time and money in acupuncture. It is also possible that consumers who have invested much time and money in acupuncture go on to rate it as very important to them, not because of any perceived effectiveness but precisely because they have invested heavily in it (akin to a form of cognitive dissonance). Although the former interpretation is more consistent with findings from earlier qualitative studies26,29 longitudinal studies are needed to tease apart causal relationships among these variables over time to better understand acupuncture use as a healthcare behavior.

It was interesting to find that acupuncture-preferred consumers used fewer CAM modalities. On the one hand, this may again suggest consumer's genuine loyalty to acupuncture (i.e., consumers preferred acupuncture and, as such, did not use other CAM modalities). On the other hand, it may suggest that acupuncture-preferred consumers may not be exposed to other CAM modalities and therefore lack the knowledge to make an informed decision. Level of expectation, level of satisfaction, and perceived effectiveness of acupuncture are other possible explanations for participants being more supportive of acupuncture.30 The latter point is somewhat supported by a survey study of CAM and conventional medicine practitioners in the United States, which revealed that CAM practitioners rated acupuncture as more effective and thus were more willing to recommend acupuncture relative to other CAM therapies, including Reiki, meditation, glucosamine, and massage.31 Notwithstanding, there is a paucity of research examining a consumer's choice to use acupuncture over other CAM modalities. Further studies assessing the comparative effectiveness of different CAM modalities and consumer perceptions of these therapies may uncover the reasons for consumers choosing certain CAM modalities over others.

Although the sex profile of acupuncture users in our analysis was consistent with that reported in Norway,32 Germany,33 Taiwan,34 and Korea35 (i.e., a higher proportion of female users relative to male users), our findings suggest that a higher proportion of men deem acupuncture to be more important to their health. One possible explanation for this finding is that men experience pain differently than women, generally with lower intensity, duration, and frequency;36 as such, men may respond differently (perhaps more favorably) to acupuncture than women. However, there is limited evidence to support this claim.37 Moreover, when the number of CAM modalities used is considered, sex becomes a nonsignificant predictor of acupuncture preference. This change may be accounted for the female-dominant profile of CAM users in general.13,38,39

Living in the western region of the United States has been previously shown to be related to a higher use of acupuncture;16,17 however, the current findings indicate that a lower proportion of respondents living in the West in the United States considered acupuncture to be the most important CAM modality for their health when compared with those living in the Northeast United States. Although no study has directly compared the regional differences of acupuncture use in the United States, the variation of familiarity of acupuncture among the population, availability and accessibility of acupuncture clinics, and insurance coverage may contribute to the diverse understanding/acceptance of acupuncture.40 Further research examining these factors and their relationship with acupuncture use may shed some light on people's acceptance and preference of acupuncture.

Our findings did not directly support the hypothesis that pain-related conditions are more prevalent among acupuncture-preferred consumers. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that as a cross-sectional survey, this study cannot establish a causal relationship between the prevalence of health conditions and a respondent's use of acupuncture,; in other words, highly prevalent conditions of the respondents are not necessarily the top reasons for use of acupuncture. In this sense, the findings probably are not contrary to previous study findings, which suggest that musculoskeletal conditions and pain are the primary health conditions treated by acupuncture.18 In this study, muscle and bone pain was the fourth most prevalent condition treated with acupuncture, while the most prevalent conditions for which acupuncture treatment was sought, regardless of preference, were head/chest colds, feeling stressed, and sore throat. Those conditions are often ignored signs of a weakened immune system.41 Use of acupuncture for these conditions is justified by several studies reporting positive effects of acupuncture on stress and immune response in diverse patient populations.42–44

In addition to the conditions mentioned above, general wellness, such as feeling worried, having trouble sleeping, and lack of energy, as well as gastrointestinal issues, such as heartburn, nausea, and vomiting, were among the most prevalent conditions reported by acupuncture users. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting acupuncture use for general wellness, stress, and/or functional gastrointestinal disorders.16,18,45 What our findings add is a broader range of conditions prevalent among acupuncture users. Given the likelihood that these conditions may coexist, future studies assessing these conditions simultaneously may provide additional insight into the potential effect of these conditions on acupuncture use.

Several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, all questions in the NHIS were self-reported, and all questions relating to health conditions and acupuncture use were asked regarding the participant's experience in the previous 12 months; hence, the study findings are potentially subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. Second, because of the nature of the cross-sectional study design, it is not possible to draw conclusions about probable causal pathways between two explored variables; therefore, the study findings should be interpreted with caution. These limitations should be balanced against the strengths of the study, including the large sample size and representativeness of the U.S. population.

Conclusion

This study has drawn new insights into acupuncture use and consumer preference. It highlights that acupuncture-preferred consumers account for 80% of acupuncture users and that user loyalty may be gained through previous benefit from acupuncture. The study also indicates that consumer preference for acupuncture appeared not to be driven by health conditions but instead was related to sociodemographic factors. This underlines the need for health education about acupuncture to be more tailored to the socioeconomic characteristics of the consumer, such as their residence. Moreover, such education or information should include not only the effectiveness of acupuncture for various health conditions but also the comparative effectiveness of acupuncture with respect to other CAM modalities for the same health conditions. Although this kind of health education may be challenging to produce, it could greatly help consumers make more informed decisions regarding acupuncture and/or other CAM modalities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the CDC for collecting the data and making NHIS datasets publicly accessible.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

List of 18 nonconventional healthcare practices: acupuncture, biofeedback, chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, craniosacral therapy, energy healing therapy, hypnosis, massage, naturopathy, traditional healing, movement therapy (Pilates/Trager psychophysical integration/Feldenkrais), herbal and nonvitamin supplementation, homeopathy, special diets, yoga/t'ai chi/qigong, and relaxation techniques (meditation/guided imagery/progressive relaxation), Ayurveda, chelation therapy, and vitamin and mineral supplementation. For the “top three question series,” all modalities were included except for Ayurveda, chelation therapy, and vitamin and mineral supplementation. These three therapies were excluded because of very low or high prevalence.16

References

- 1.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 1998;280:1569–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes P, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. CDC Advance Data Report 2004. #343 [PubMed]

- 3.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Rep 2009:1–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997–2002. Altern Ther Health Med 2005;11:42–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Acupuncture: An Introduction. NCCAM Publication No. D404 2007. Online document at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/acupuncture/introduction.htm Accessed July5, 2011

- 6.MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, Fitter M. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ 2001;323:486–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopton A, MacPherson H. Acupuncture for chronic pain: is acupuncture more than an effective placebo? A systematic review of pooled data from meta-analyses. Pain Pract 2010;10:94–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1444–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke A, Upchurch DM, Dye C, Chyu L. Acupuncture use in the United States: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med 2006;12(7):639–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Bloom B. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Rep 2009:1–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank R, Stollberg G. Medical acupuncture in Germany: patterns of consumerism among physicians and patients. Sociol Health Illn 2004;26:351–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eardley S, Bishop FL, Prescott P, et al. A systematic literature review of complementary and alternative medicine prevalence in EU. Forsch Komplementmed 2012;19 Suppl 2:18–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue CC, Zhang AL, Lin V, Da Costa C, Story DF. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: a national population-based survey. J Altern Complement Med 2007;13:643–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopton AK, Curnoe S, Kanaan M, Macpherson H. Acupuncture in practice: mapping the providers, the patients and the settings in a national cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke A, Upchurch DM, Dye C, Chyu L. Acupuncture use in the United States: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med 2006;12:639–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Lao L, Chen H, Ceballos R. Acupuncture use among American adults: what acupuncture practitioners can learn from National Health Interview Survey 2007? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:710750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upchurch DM, Burke A, Dye C, Chyu L, Kusunoki Y, Greendale GA. A sociobehavioral model of acupuncture use, patterns, and satisfaction among women in the United States, 2002. Womens Health Iss 2008;18:62–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Upchurch DM, Rainisch BW. A sociobehavioral wellness model of acupuncture use in the United States, 2007. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:32–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cochrane S, Smith CA, Possamai-Inesedy A, Bensoussan A. Acupuncture and women's health: an overview of the role of acupuncture and its clinical management in women's reproductive health. Int J Womens Health 2014;6:313–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chien TJ, Liu CY, Hsu CH. Integrating acupuncture into cancer care. J Trad Complement Med 2013;3:234–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennehy EB, Webb A, Suppes T. Assessment of beliefs in the effectiveness of acupuncture for treatment of psychiatric symptoms. J Altern Complement Med 2002;8:421–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bishop FL, Lewith GT. Patients' preconceptions of acupuncture: a qualitative study exploring the decisions patients make when seeking acupuncture. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;13:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassidy CM. Chinese medicine users in the United States. Part II: Preferred aspects of care. J Altern Complement Med 1998;4:189–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould A, MacPherson H. Patient perspectives on outcomes after treatment with acupuncture. J Altern Complement Med 2001;7:261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths V, Taylor B. Informing nurses of the lived experience of acupuncture treatment: a phenomenological account. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2005;11:111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paterson C, Britten N. Acupuncture as a complex intervention: a holistic model. J Altern Complement Med 2004;10:791–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Rep 2008:1–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release: NHIS Survey Description. 2013. Online document at: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2012/srvydesc.pdf, accessed March9, 2015

- 29.Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith GT. Why consumers maintain complementary and alternative medicine use: a qualitative study. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, et al. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2007;128:264–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilburt JC, Miller FG, Jenkins S, et al. Factors that influence practitioners' interpretations of evidence from alternative medicine trials: a factorial vignette experiment embedded in a national survey. Med Care 2010;48:341–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohre A, Steinsbekk A, Rise MB. Characteristics of female and male visitors to practitioners of acupuncture in the HUNT3 Study. Am J Chin Med 2013;41:995–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cramer H, Chung VC, Lauche R, et al. Characteristics of acupuncture users among internal medicine patients in Germany. Complement Ther Med 2015;23:423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shih CC, Liao CC, Su YC, Tsai CC, Lin JG. Gender differences in traditional Chinese medicine use among adults in Taiwan. PLoS One 2012;7:e32540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee YS, Lee IS, Kim SY, et al. Identification of determinants of the utilisation of acupuncture treatment using Andersen's behavioural model. Acupunct Med 2015;33:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund I, Lundeberg T. Is it all about sex? Acupuncture for the treatment of pain from a biological and gender perspective. Acupunct Med 2008;26:33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu WQ, Claunch J, Kong J, et al. The effects of acupuncture on the brain networks for emotion and cognition: an observation of gender differences. Brain Res 2010;1362:56–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Leach MJ, Hall H, et al. Differences between male and female consumers of complementary and alternative medicine in a national US population: a secondary analysis of 2012 NIHS data. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:413173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunt KJ, Coelho HF, Wider B, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in England: results from a national survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1496–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu DP, Lu GP. An historical review and perspective on the impact of acupuncture on U.S. medicine and society. Med Acupunct 2013;25:311–316.41. Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008;9:46–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pavao TS, Vianna P, Pillat MM, Machado AB, Bauer ME. Acupuncture is effective to attenuate stress and stimulate lymphocyte proliferation in the elderly. Neurosci Lett. 2010;484:47–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arranz L, Guayerbas N, Siboni L, De la Fuente M. Effect of acupuncture treatment on the immune function impairment found in anxious women. Am J Chin Med 2007;35:35–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petti F, Bangrazi A, Liguori A, Reale G, Ippoliti F. Effects of acupuncture on immune response related to opioid-like peptides. J Trad Chin Med. 1998;18:55–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi T. Acupuncture for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastroenterol 2006;41:408–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]