Abstract

The epidemics of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have spread among older adults in the world, including China. This study addresses the deficiency of studies about the multiple contextual influences on condom use among mid-age female sex workers (FSWs) over 35 years old. A combination of an egocentric network design and multilevel modeling was used to investigate factors of condom use over mid-age FSWs (egos) particular relationships with sexual partners (alters). Of the 1245 mid-age FSWs interviewed, 73% (907) reported having at least one sexual partner who would provide social support to egos. This generated a total of 1300 ego–alter sex ties in egos' support networks. Condoms were consistently used among one-third of sex ties. At the ego level, condoms were more likely to be used consistently if egos received a middle school education or above, had stronger perceived behavioral control for condom use, or consistently used condoms with other sex clients who were not in their support networks. At the alter level, condoms were not consistently used over spousal ties compared to other ties. Condoms were less likely to be used among alters whom ego trusted and provided emotional support. Cross-level factors (egos' attitudes toward condom use and emotional support from alters) documented a significant positive interaction on consistent condom use. Given the low frequency of condom use, future interventions should focus on mid-age FSWs and their partners within and beyond their support networks.

Introduction

Epidemiologic data from both developed and developing countries suggest that sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, have spread rapidly among older adults over 50 years old.1,2 Paralleling the new global epidemic, the number of older cases of HIV/STIs in China has quickly increased in the past years.3,4 Previous studies have documented that a majority of older HIV/STI cases in China reported a history of commercial sex with mid-age female sex workers (FSWs) over 35 years old.5,6 According to the findings from recent studies, mid-age FSWs in China enter the commercial sex industry for survival sex in their 30s.5,6

Different from younger FSWs, mid-age FSWs are usually married, do not have a stable job, and are required to earn money to support families, including children. Younger FSWs enter the sex trade at a younger age and typically do not have the financial burden of supporting a family.7–9 In fact, after younger FSWs make enough money they usually quit the sex industry in their 30s to open small private businesses.

Previous research in China and other developing countries have examined the epidemics of HIV/STIs and their potential determinants among predominantly younger FSWs.10–12 However, the findings from these studies may not apply to mid-age FSWs because they exhibit different social and behavioral risk factors for STIs. New biomedical and behavioural research is warranted among this vulnerable population.

The social network model provides a powerful approach for studies of diffusion of social influence and transmission of diseases.13 This approach that integrates both key individual and broader social network elements offers better understanding of disease transmission and generates valid information to design sustainable interventions and prevention programs that can be broadly disseminated.14 Research has identified two roles of networks in the transmission of HIV/STIs:15,16 (1) the role as vectors of disease transmission from one person to another by risk behaviors, or risk networks, and (2) the role as generators and disseminators of social influence, or social networks.

The first role refers to the actual transmission of viral pathogens from one person to another by risk behaviors. The second role describes the extent to which network members encourage or discourage engagement in risky behaviors, which facilitates HIV/STI tansmissions.17,18 Previous research has documented that risk networks become part of the social network since individuals not only engage in risk behavior, but also exchange social support or influence.15,19 Attitudes and behaviors are reinforced when they are shared with network members, but are more likely to be altered or discouraged when they are discrepant,20 which may be especially true among individuals with a collectivist culture.

The social network approach for studying sexual risk may be particularly useful in the Chinese collectivist culture, which emphasizes interdependence within personal network and harmony in social environments.21 People in the collectivist culture tend to see themselves as interdependent within groups; behaving according to group needs and maintaining harmony within the community.22,23 Chinese people are encouraged to make decisions within the sphere of influence of their partners, peers, family members, or supervisors,24–26 but place less emphasis on self-reliance and independence.27 They believe that group identity is more important than an individual one and are more likely to sacrifice their own interests to promote the collective good.28 Following the features of this culture, we expect that the decision to engage in sexual risk behavior may be heavily influenced by network peers, especially those who do not take preventive measures for safer sex.

Identification of the two roles of networks may help to explain the diffusion of social influence, engagement in risky sexual behavior, and transmission of STIs among mid-age FSWs. As a special form of social networks, egocentric networks consist of an index person (ego) and his/her sexual partners (alters). In this study, egos are FSWs and their commercial and noncommercial sexual partners are alters. The above mentioned two roles co-exist in egocentric sexual networks as sex workers and their partners do not only engage in sexual behavior, but share personal perceptions, attitudes, support, and influence related to sexual risk or safer sex. While the two roles of networks in the transmission of HIV/STIs have been well studied among men who have sex with men,29 illicit drug users,30 and younger sex workers,31 they have not been investigated among mid-age FSWs.

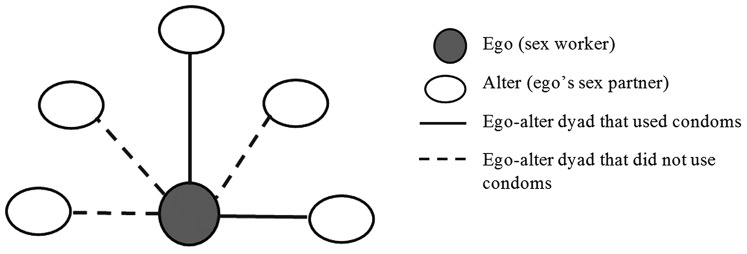

Consistent condom use remains a cost-effective approach for reducing HIV/ STI transmission in egocentric networks. The decision to use condoms is made by two individuals involved in sexual contact, which occurs at the dyadic level. For example, if a sex worker has five sex partners (Fig. 1), she has five ego–alter ties or dyads in her sexual network. She may consistently use condoms with only two partners, not with the other three. The traditional research approach that addresses individual-level factors (i.e., at the ego level) cannot answer the question regarding why that particular sex worker engages in safer sex with two partners, not others. The social network approach can be used to address that question as it takes into consideration potential factors for condom use at both intrapersonal and interpersonal (or dyadic network) level and factors across the two levels.

FIG. 1.

A sexual network of an ego.

At the intrapersonal level, the decision to use condoms may be determined by factors from egos and alters: for example, their demographic characteristics,32 attitudes towards condom use,33 perceived control for condom use,34 and sex-work related stigma.8 Similarly, consistent condom use may also be influenced by interpersonal factors or dyadic factors, for example, differences in age between egos and alters,35 commercial sex locations,36 exchanging sex for drugs,37 sex concurrency,38 network support,13 and network norms.39

Research has documented that factors regulating condom use cannot be fully captured by a single measure at one level, but requires attention to interpersonal (or network) and intrapersonal (or individual) level factors as well.13 Therefore, a social network approach that allows the inclusion of multilevel influences at both intrapersonal and interpersonal levels should be applied to study condom use among mid-age FSWs. The relationships and interactions that occur within social networks are considered critical to understanding sexual behavior and HIV/STI risk.40 Social network studies collect rich data within and between egos and alter levels.

Specific analytic approaches need to be employed to exploit multiple levels of data to disentangle the effects due to factors at each specific level.41 Multilevel network analysis has been used in a limited number of social network studies, including: adolescent drinking,42 unprotected sex of homeless youth,43 personal support networks of immigrants,44 and the role of health discussion among partners to help recover from mental illness.45

In this study, we address the lack of empirical studies using multiple contextual influences on condom use among mid-age FSWs. A combination of an egocentric network design and multilevel analytic approach was used to understand multilevel factors associated with condom use over mid-age FSWs' particular relationships with their sexual partners. Multilevel modeling permits simultaneously testing multiple levels of influence (ego and alter characteristics, social network components, and cross-level interactions) on condom use within egocentric sexual networks.

The aims of this study were to describe the individual and social network characteristics of mid-age FSWs (egos) and their male partners (alters) and to examine the associations between network factors and consistent condom use. Based on social network theory,13 the theory of planned behavior,46 and our previous social network studies,19,47 particularly the qualitative studies among mid-age FSWs,6,48 we conceptualized the following hypotheses that were tested in this study: (1) at the ego level, egos' attitudes and perceived behavioral control towards condom use are positively associated with consistent condom use; (2) the frequency of condom use over the ego–alter ties will be either increased or decreased depending on alters' relationships with ego and level of social support received; and (3) there will be interaction effect between ego and alter factors on consistent condom use.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Maryland, Shandong University School of Public Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Hefei and Guangxi. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study methods have been previously described in detail.49

Study subjects

An egocentric network study was carried out at three study sites in 2014: Qingdao (north), Hefei (central), and Nanning (south) China. The reasons for selecting these three sites included (1) geographic coverage from northern China down to the south; (2) capture of variation in the number of STDs; and (3) previous collaborations with researchers in these three cities. According to the local surveillance data and China National HIV/STD Surveillance,50 Nanning is located in the area with the highest HIV/STI prevalence (8618 HIV cases and 36,404 notifiable STI cases reported from 2010 to 2013), Hefei with mid-level prevalence (1105 HIV cases and 21,344 STI cases), and Qingdao with the lowest prevalence (733 HIV cases and 8748 STI cases).

Subjects were recruited into the study if: (1) they were female and lived in either of the three cities for at least 3 months; (2) were at least 35 years old; and (3) had exchanged sex for money at least once a week in the past month prior to interview. Mid-age FSWs were defined as sex workers over 35 years old. The 35-year-cut point was based on the findings from our previous qualitative studies conducted at the three study sites.6,48

Recruitment of study subjects

Respondent-driven sampling (RDS) was used to recruit participants.51,52 The reason for selecting RDS rather than a venue-based sampling approach was to utilize a sampling framework that included eligible subjects who did not work in venue-based brothels (for example, soliciting clients along streets or in parks). Four or five seeds were selected from each site. The selection of seeds was based on the results from our qualitative study and suggestions from mid-age FSWs. All seeds received an explanation of the study purpose and procedures, as well as three coupons to recruit up to three eligible subjects. The number of recruitment waves reached for each study site was eight in Qingdao, nine in Hefei, and eleven in Nanning. Applications of RDS have demonstrated that a broad cross-section of the hidden population becomes a representative sample after five to six recruitment waves.51

Convergence plots and bottleneck plots were used to determine whether the final RDS estimates were biased by the initial convenience sample of seeds.53,54 Five variables were used in the convergence analysis including: age, education, marital status, migration status, and client solicitation location. Convergence was reached (e.g., the proportions of the five variables remained unchanged in the later recruitment waves) after 100–300 subjects were recruited at each site. Therefore, our evaluation of this RDS sample at each study site indicated success in reaching the convergence of RDS compositions and included a broad cross-section of the mid-age FSW population.

A sample size of 400 subjects at each study site was estimated to ensure a sufficient number of recruitment waves were obtained (e.g., at least five). In addition, a sample size of 400 produced a two-sided 94% confidence interval with a width equal to 0.06 when the sample proportion was 0.10.55 According to previous reports,56,57 the prevalence of syphilis was about 10% among FSWs in China.

Interviews

All eligible subjects, including those recruited by seeds and new recruits in subsequent waves, participated in a face-to-face anonymous interview in a private room. Interviewers used computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) to interview subjects. Interviewers at each site received training on interviewing techniques, developing rapport, answering subjects' questions, and participant confidentiality. Interviews were held at the clinics, hotels, and the local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These sites were chosen for their proximity to participants (less than 1 h-travel time) and to ensure participant confidentiality.

Social support networks

Interview questions were drafted in English and then translated into Chinese by our team members who were fluent in both languages. Both qualitative (cognitive interviewing with 18 mid-age FSWs in Hefei) and quantitative (pilot of the questionnaire among 60 mid-age FSWs in Nanning) techniques were used to test the psychometric properties of the CAPI questionnaire. Measurement questions and scales were revised based on the findings from these pilots.

The Chinese Social Network Questionnaire (CSNQ) was used to capture the social support network of egos, which has been used and validated in our previous network studies.58,59 To delineate social networks, name-generating questions were used to ask respondents (egos) to list, by giving the first names or pseudonyms of alters who would provide them support in each of the two support domains (emotional and tangible support). Alters could be friends, family members, relatives, pimps, venue owners, FSWs, or others whom the respondents knew for at least 1 month.

Each of the two support domains was operationalized with three items.60 For tangible support, egos were asked to list alters who would (1) lend the ego 200 Chinese dollars ($30 US); (2) take care of the ego, if the ego were confined to bed for 2–3 weeks; and (3) help or advise the ego if the ego had problems regarding family or health issues. To assess emotional support, egos were asked to name alters who would (1) agree with or support the ego's ideas or actions; (2) make the ego feel respected or admired; and (3) convince the ego to confide in the alter. Ego's social support networks comprised of all individuals who were perceived to provide at least one of the six types of support to egos.

Sexual networks and consistent condom use

Sexual network was a subset of social support networks. After naming alters who were perceived to provide social support to egos, egos were asked to indicate with which alters they had sexually engaged. Alters who were in egos' support network and engaged in sex with egos constituted the sexual risk networks of egos. The frequency of condom use in the most recent month was assessed with five possible answers (0: never used condoms; 1: used condoms in less than half of sex acts; 2: used condoms in about half of sex acts; 3: used condoms most of the time; and 4: used condoms during every sex act). Consistent condom use was defined as having used condoms for most or all sex acts. This dichotomous variable (consistent condom use vs. inconsistent or no condom use) was used as the dependent variable in the multilevel modeling analysis.

Measures at the ego level

Attitudes towards condom use were measured by an 8-item scale that was validated in our previous study (e.g., “It is not necessary to use condoms if you trust your partner”).33 Response categories ranged from (0) ‘strongly disagree’ to (3) ‘strongly agree’. The reversed composite score ranged from 0–24. Higher scores indicated more favourable attitudes toward condom use. The Cronbach's reliability alpha was 0.73.

Perceived behavioral control was measured by six items with a 4-point response scale: very unlikely (0), unlikely (1), likely (2), to very likely (3) (sample item: “If a client gives you more money to have unprotected sex, how likely is it that you could persuade him to use condoms?”; Cronbach's alpha = 0.82; score range: 0–18).

Condom use was measured in two ways: condom use with the most recent sexual partners and the frequency of condom use with commercial casual clients in the past month. Egos' condom use with their most recent sexual partners in the past 48 h prior to interview was bio-tested by the prostate specific antigen (PSA). The presence of PSA is detectable in vaginal discharge for 48 h after acts of unprotected vaginal intercourse.61,62 The test is 100% sensitive [95% confidence interval (CI): 98–100%] and 96% specific (95% CI: 93–97%) for testing PSA within 48 h after vaginal intercourse.61

Egos' condom use with casual commercial clients (most of them did not provide social support to egos, thus not in their support network) was measured by a 7-item scale that assessed condom use in the last month under different scenarios (e.g., frequency of condom use when clients gave incentives for condomless sex; condom use when mid-age clients had erectile dysfunction; or frequency of condom-less sex due to unavailability of condoms). Response categories ranged from (0) ‘never happened’, (1) ‘sometimes happened’, (3) ‘happened’, to (4) ‘always happened’. A higher score indicates more frequent condom use (Cronbach's alpha = 0.78; score range: 0–28). In addition, ego's age, education, marital status, rural-to-urban migrant status, and duration of sex work were obtained.

Measures at the alter level

The levels of tangible and emotional support were calculated by summing the alters' three types of perceived support in each domain. Four response categories indicating whether the alter would provide support to ego ranged from: (0) no support; (1) unsure if the alter would provide support; (2) possible support; and (3) definitely provide support. For both tangible and emotional support, higher scores indicated more support (range: 0–9). Alter–ego relations included husband, relatives, boyfriend, sex clients, and others (e.g., pimps, sex venue managers, or acquaintances). Degree of trust was measured on a 5-point Likert scale and was asked by the item “Please tell me your degree of trust toward each alter.” Possible response options included: 0: do not trust at all; 1: do not trust; 2: neutral; 3: trust; and 4: trust very much. Alter's age, education level, and marital status were also asked.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis was conducted to describe the mean and median of continuous variables and proportions of categorical variables. The interquartile range (IQR) was estimated as the 25th to the 75th percentile.

To identify factors associated with condom use over the ego–alter ties, a multilevel random intercept model was used to disentangle the effects due to ego characteristics, alter attributes, cross-level difference (heterogeneity), and cross-level interactions.41,63 The dependent variable was whether condoms were consistently used at each ego–alter sexual tie or dyad (1: consistent condom use; 0: inconsistent condom use). The egocentric network data has a two-level structure with ego at the higher level, or level 2, and alter at the lower level, or level 1. Because the dependent variable was binary, this multilevel logistic regression model was used:

|

pij is the probability that the tie between ego j and alter i is valued 1 (consistent condom use), given the explanatory information from ego and alter. βs are fixed effects, which may be the characteristics of the alter i within ego j (x1ij; e.g., alter i's age or gender) characteristics of the ego (x2j; ego j's age or gender), and cross-level interaction terms (x1ijx2j). U0j is a random effect for the intercept of the regression model at the ego level. That is, U0j is an ego-level (level 2) residual term which we assume is normally distributed with mean zero and variance, σ2u0. σ2u0 is the ego-level variance component, measuring the extent to which the average values (log-odds) of the ties in one ego's network vary from one another.

The hierarchical modeling approach was used to examine how ego factors, alter factors, and cross-level factors operated independently and collectively on the outcome variable (dependent variable) and within the context of a full model, which includes all independent variables.45 Our model formulation included three hierarchical steps. Model one included only ego characteristics. In model two, alter characteristics were added into model 1. The full or final model, model 3, cross-level differences and interactions were added to model 2. We included dummy variables for the study sites in this model, rather than treating them as the third level, since there were only three sites.44

Two model fit statistics (−2 log likelihood or −2LL and Akaike's information criterion or AIC) were used to assess the fitness of models to data. A smaller value of these criteria indicates better model fit. In addition, likelihood ratio test was used to statistically test the model fit. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to conduct statistical analyses.

Results

Egos characteristics

A sample of 1245 mid-age FSWs (egos) were recruited and interviewed at the three study sites (418 in Nanning, 407 in Hefei, and 420 in Qingdao). As depicted in Table 1, the majority of egos were between 35–40 years old (60.5%), married (49%) or divorced/widowed (41.7%), rural-to-urban migrants (69.5%), and received a middle school education (46.3%) or no-school or a primary school education (43.9%). The median duration of sex work was 3.17 years (interquartile range: 1.33–5.83).

Table 1.

Ego Characteristics and Condom Use Among Mid-Age Female Sex Workers (N = 1245)

| N (%) | Supporting network size | Sexual network size | Tangible support | Emotional support | % Consistent condom useb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | p < 0.01 | p = 0.40 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p = 0.02 | |

| 35–40 | 753 (60.5) | 4.95 (2.23)a | 1.07 (0.94) | 30.46 (16.40) | 25.25 (15.83) | 0.32 |

| 41–45 | 249 (20.0) | 4.37 (2.42) | 0.98 (0.80) | 27.14 (16.68) | 21.56 (15.20) | 0.26 |

| 46–50 | 160 (12.9) | 4.23 (2.28) | 0.99 (1.00) | 26.47 (15.25) | 20.99 (13.87) | 0.22 |

| >50 | 83 (6.6) | 4.41 (1.99) | 1.14 (1.14) | 26.85 (13.05) | 21.83 (11.85) | 0.20 |

| Education | p < 0.01 | p = 0.12 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | |

| No school or primary school | 546 (43.9) | 4.42 (2.22) | 0.98 (0.90) | 26.67 (15.34) | 21.36 (14.40) | 0.22 |

| Middle school | 577 (46.3) | 4.92 (2.35) | 1.09 (0.92) | 30.69 (16.73) | 25.22 (15.92) | 0.33 |

| High school or above | 122 (9.8) | 4.98 (2.13) | 1.10 (1.17) | 31.88 (15.97) | 27.35 (15.02) | 0.43 |

| Marriage | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p = 0.01 | |

| Married | 610 (49.0) | 4.92 (2.36) | 1.21 (0.93) | 30.49 (16.45) | 25.10 (15.77) | 0.26 |

| Single | 116 (9.3) | 4.72 (2.02) | 0.94 (1.02) | 30.52 (15.98) | 24.41 (13.27) | 0.39 |

| Divorced or widowed | 519 (41.7) | 4.45 (2.22) | 0.88 (0.89) | 27.03 (15.73) | 21.99 (15.08) | 0.32 |

| Rural-to-urban migrant | p = 0.43 | p < 0.01 | p = 0.37 | p = 0.04 | p = 0.76 | |

| No | 380 (30.5) | 4.63 (2.13) | 1.17 (0.99) | 28.43 (14.94) | 22.41 (13.89) | 0.29 |

| Yes | 865 (69.5) | 4.74 (2.34) | 0.99 (0.91) | 29.32 (16.71) | 24.33 (15.89) | 0.30 |

| Duration of sex work (years) | p < 0.01 | p = 0.11 | p < 0.01 | p = 0.01 | p = 0.97 | |

| 0–1 | 265 (21.3) | 4.21 (2.32) | 0.94 (0.98) | 26.50 (15.06) | 22.30 (14.52) | 0.29 |

| 2–3 | 349 (28.0) | 4.85 (2.32) | 1.12 (0.98) | 30.45 (16.37) | 23.93 (14.94) | 0.30 |

| 4–5 | 294 (23.6) | 5.23 (2.41) | 1.07 (0.86) | 32.54 (18.30) | 26.18 (17.29) | 0.29 |

| >5 | 337 (27.1) | 4.49 (1.98) | 1.03 (0.92) | 26.55 (14.08) | 22.55 (14.27) | 0.29 |

| Condom use in the past 48 h | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | |

| Yes | 712 (57.6) | 4.93 (2.37) | 1.17 (0.99) | 31.46 (16.88) | 26.23 (15.78) | 0.33 |

| No | 523 (42.4) | 4.40 (2.12) | 0.18 (0.94) | 25.77 (14.55) | 20.38 (14.03) | 0.24 |

Mean and standard deviation.

Number of alters with whom ego consistently used condoms divided by number of ego's sex partner alters.

Support networks, sexual networks, and condom use at the ego level

The 1245 egos reported a total of 5858 alters who could provide the two types of social support to them (egocentric support networks), resulting in the mean network size of 4.7 (5858/1245). Egos who were between 35–40 years old, received a high-school or above education, were either married or single, or worked in commercial sex for 4–5 years had a larger network size and received higher tangible and emotional support from alters (Table 1).

Of the 1245 egos, 73% (907) egos reported having had sex with 1300 alters (22% of their supporting alters in their support networks), among whom, 648 egos had one sexual partner (71.4%), 164 egos had two partners (18.1%), 88 egos had three to four partners (9.7%), and about 0.8% of egos had five or six partners. The average size of sexual networks was 1.4. Consistent condom use with at least one alter was 34.2% (310/907). The test of PSA, a biomarker for condom use, indicated that 42.4% (523/1235, 10 egos did not receive a PSA test) of the egos did not use condoms within the past 48 h prior to interview. Relatively, consistent condom use was higher among egos who were young, single, received more education, and used condoms with their most recent partners (Table 1).

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) showed that the percentage of consistent condom use was correlated with attitudes towards condom use (0.27, p < 0.01) and perceived behavioral control of condom use (0.19, p < 0.01). Egos who consistently used condoms with partners who provided support in their support networks were also more likely to consistently use them with casual commercial clients who did not provide support (not in support networks) (r = 0.17, p < 0.01).

Alter characteristics and condom use at the alter level

Relationships between sexual-partner alters and their egos included egos' commercial sex clients (37.3%), husbands (31.8%), boyfriends (27.5%), and other relations (3.5%; i.e., relatives, pimps, venue managers, or acquaintances). The majority of alters were over 40 years old, had a middle or high school education, or were married. There were more alters who were older than egos (41.7%) than alters who were younger than egos (12.8%). Two-thirds (71.3%) of ego–alter sex ties were trusted ties (Table 2).

Table 2.

Alter Characteristics and Condom Use Among Mid-Age Female Sex Workers (N = 1300)

| Consistent condom use (n = 462) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | OR (95% CI)a | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤34 | 85 (6.5) | 39 (45.9) | 1 |

| 35–39 | 297 (22.8) | 100 (33.7) | 0.66 (0.37–1.17) |

| 40–44 | 402 (30.9) | 150 (37.3) | 0.78 (0.45–1.37) |

| >40 | 516 (39.8) | 173 (33.5) | 0.66 (0.38–1.16) |

| Education | |||

| No school or primary school | 201 (15.5) | 41 (20.4) | 1 |

| Middle school | 528 (40.6) | 150 (28.4) | 1.45 (0.93–2.27) |

| High school or above | 394 (30.3) | 169 (42.9) | 2.79 (1.76–4.41)c |

| Unknown | 177 (13.6) | 102 (57.6) | 5.82 (3.42–9.90) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 959 (73.8) | 356 (37.1) | 1 |

| Single | 120 (9.2) | 48 (40.0) | 1.08 (0.69–1.69) |

| Divorced or widowedb | 221 (17.0) | 58 (26.2) | 0.59 (0.41–0.86) |

| Relation to ego | |||

| Husband | 413 (31.8) | 57 (13.8) | 1 |

| Boyfriends | 357 (27.5) | 115 (32.2) | 3.00 (2.02–4.45) |

| Clients | 485 (37.3) | 273 (56.3) | 8.26 (5.70–11.97) |

| Othersd | 45 (3.5) | 17 (37.8) | 3.24 (1.50–7.03) |

| Ego-alter age difference | |||

| Same | 591 (45.5) | 171 (28.9) | 1 |

| Ego is older | 167 (12.8) | 70 (41.9) | 1.73 (1.14–2.62) |

| Alter is older | 542 (41.7) | 221 (40.8) | 1.76 (1.31–2.36) |

| Ago-alter trust | |||

| Do not trust | 105 (8.1) | 39 (37.1) | 1 |

| Not sure | 268 (20.6) | 148 (55.2) | 1.97 (1.12–3.45) |

| Trust | 648 (49.8) | 216 (33.3) | 0.74 (0.44–1.24) |

| Trust very much | 279 (21.5) | 59 (21.2) | 0.39 (0.22–0.70) |

| Mean (standard deviation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistent use | Non-consistent use | ||

| Tangible support | 5.52 (2.11) | 6.73 (1.94) | 0.73 (0.68–0.78) |

| Emotional support | 4.69 (1.99) | 4.95 (2.19) | 0.93 (0.87–0.99) |

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Including 17 alters with unknown marital status.

Bold indicating p < 0.05.

Relatives, pimps, venue managers, or acquaintances.

One third (35.5%, 462/1300) of the ego–alter sex ties consistently used condoms. Bivariate analysis indicated consistent condom use was positively associated with a high school education or above (compared with no school or primary school education), relationships to ego (boyfriends, clients, or other relations compared to spousal relations), and ego–alter differences in age compared to ego–alter ties of similar ages. It was negatively associated with a higher degree of trust, and being divorced or widowed. Both tangible support and emotional support were negatively associated with consistent condom use (Table 2).

Multilevel modelling

Multilevel analysis was performed among 1300 ego-alter sex ties. Model 1 only included ego characteristics as explanatory variables and consistent condom use as the dependent variable. Egos who received a middle school or above education or who were widowed/divorced were more likely to consistently use condoms than egos who received no education or primary education or who were married. Attitudes toward condom use were positively associated with consistent condom use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations Between Network Factors at the Ego and Alter Level and Consistent Condom Use: Multilevel Logistic Regression Models (N = 1300)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CIa | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | |

| Ego factors | ||||||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | 0.98 | 0.94–1.02 |

| Middle school vs. no school or primary school | 1.47 | 1.08–2.01b | 1.39 | 0.97–2.00 | 1.53 | 1.06–2.23 |

| High school vs. no school or primary school | 2.19 | 1.31–3.66 | 1.98 | 1.10–3.56 | 2.28 | 1.25–4.14 |

| Single vs. married | 1.29 | 0.75–2.21 | 0.67 | 0.33–1.35 | 0.71 | 0.34–1.45 |

| Widowed/divorced vs. married | 1.60 | 1.16–2.20 | 0.82 | 0.54–1.25 | 0.97 | 0.63–1.50 |

| Migrant (yes vs. no) | 0.87 | 0.63–1.19 | 0.83 | 0.58–1.19 | 0.86 | 0.60–1.24 |

| Duration of sex work (in years) | 1.00 | 0.95–1.04 | 1.00 | 0.95–1.06 | 1.04 | 0.98–1.11 |

| Condom use with casual clients in the past month | 1.06 | 0.99–1.13 | 1.09 | 1.01–1.18 | 1.09 | 1.01–1.19 |

| Condom use in past 48 h (PSA) | 0.89 | 0.66–1.21 | 0.93 | 0.66–1.32 | 1.02 | 0.72–1.46 |

| Attitudes towards condom use | 1.16 | 1.09–1.23 | 1.21 | 1.13–1.29 | 1.17 | 0.96–1.42 |

| Perceived behavioral control for condom use | 1.05 | 0.97–1.13 | 1.10 | 1.02–1.20 | 1.11 | 1.01–1.21 |

| Alter factors | ||||||

| Age (≥ 35 vs. <35) | 0.79 | 0.43–1.46 | 1.21 | 0.50–2.90 | ||

| Middle school vs. no or primary school | 0.84 | 0.50–1.43 | 0.86 | 0.50–1.48 | ||

| High school vs. no or primary school | 1.06 | 0.60–1.85 | 0.96 | 0.54–1.69 | ||

| Unknown vs. no or primary school | 1.65 | 0.87–3.14 | 1.90 | 0.99–3.67 | ||

| Single vs. married | 0.61 | 0.33–1.15 | 0.59 | 0.31–1.14 | ||

| Widowed/divorced vs. married | 0.54 | 0.34–0.87 | 0.52 | 0.32–0.83 | ||

| Boyfriend vs. husband | 4.40 | 2.61–7.42 | 4.28 | 2.51–7.33 | ||

| Client vs. husband | 8.79 | 5.15–15.00 | 8.23 | 4.78–14.19 | ||

| Other relations vs. husbandc | 3.46 | 1.52–7.88 | 3.75 | 1.60–8.80 | ||

| Tangible support | 0.85 | 0.76–0.95 | 1.11 | 0.74–1.67 | ||

| Emotional support | 1.06 | 0.97–1.17 | 0.64 | 0.42–0.98 | ||

| Trust | 0.78 | 0.63–0.96 | 0.82 | 0.66–1.01 | ||

| Cross-level difference/interaction | ||||||

| Ego older than alter vs. similar age | 1.61 | 0.84–3.12 | ||||

| Alter older than ego vs. similar age | 1.02 | 0.69–1.51 | ||||

| Attitude towards condom use X tangible support | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 | ||||

| Attitude towards condom use X emotional support | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 | ||||

| Hefei vs. Nanning | 1.13 | 0.74–1.74 | ||||

| Qingdao vs. Nanning | 0.44 | 0.27–0.71 | ||||

| Model fit | ||||||

| AIC | 1496.5 | 1196.05 | 1186.03 | |||

| −2LL | 1470.5 | 1146.05 | 1124.03 | |||

| p Value (likelihood ratio test) | Model 2 vs. 1: p < 0.01 | Model 2 vs. 3: p < 0.01 | ||||

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Bold indicating p < 0.05.

Relatives, pimps, venue managers, or acquaintances.

In Model 2, alter attributes as explanatory variables were added to Model 1. Alters' relations with egos were significantly associated with condom use. Specifically, compared with husband alters, condoms were more likely to be consistently used with client alters, boyfriend alters, and alters with other relations to ego. Alters who provided a higher level of tangible support or who were trusted by egos were less likely to consistently use condoms with egos. Compared with Model 1, the inclusion of alter attributes led to a significant improvement in the model fit according to the −2LL, AIC, and likelihood ratio test.

The full model (Model 3) that included cross-level differences in age, attitude–support interactions, and study site further significantly improved the model fit, compared with Model 2. The cross-level factor (attitudes to condom use from egos and emotional support from alters) depicted a significant positive interaction effect on consistent condom use, indicating an ego–alter pair was more likely to use condoms if the ego had a greater positive attitudes towards condom use and alters provided a higher level of emotional support. However, the interaction effect of attitudes to condom use and tangible support on condom use was small and did not reach the statistical significance.

The heterogeneity of age was not significantly associated with condom use. Compared with mid-age FSWs in Nanning, mid-age FSWs in Qingdao were less likely to use condoms consistently. The interaction effect between perceived behavioral control and social condom use was small and not significant. The interaction terms were removed from this model as their inclusion did not improve the model fit.

As indicated in Model 3, at the ego level, condoms were more likely to be consistently used between ego–alter sex ties if the ego received a middle school or higher education, had stronger perceived behavioral control for condom use, or consistently used condoms with casual sex clients in the past month. At the alter level, alters' relations to egos were strongly associated with condom use. That is, condoms were consistently used with egos' boyfriends, clients, or other relations, compared to husband relations. Condoms were less likely to be used with alters who were: trusted by egos, provided a higher level of emotional support, and were more densely connected.

Discussion

The findings of this study clearly document that the frequency of condom use was too low to prevent the spread of HIV/STIs among mid-age FSWs and sexual-partner alters in their networks. Consistent condom use over the ego–alter ties was potentially determined by multiple factors at both the ego and alter level and factors across the two levels. The findings also suggest that mid-age FSWs are at an elevated risk to acquire HIV/STIs from their sexual partners and transmit infections to alters in their support networks and further to casual clients beyond the networks. The multilevel analytic approach provides a useful tool to clearly depict the degree to which factors at each level potentially influence condom use. The findings also support the use of the social network model to understand behavior change at both the intrapersonal and interpersonal level.

At the ego level, only about one-third of egos consistently used condoms with alters in their sexual network and 42% of egos used condoms with their most recent partners in the past 48 h (most of whom were commercial casual partners and not in egos' support networks). The low condom use is concerning and indicates a high possibility that STIs could spread outside the closed loop of casual clients to the general population of supporting alters. This possibility is also supported by another finding that showed that mid-age FSWs who did not consistently use condoms with casual clients outside of their support networks (i.e., condom use with casual clients in the past month) were also less likely to use them with alters who were in their support networks.

Unless effective intervention programs are implemented, the epidemics of HIV/STIs may continue to spread among mid-age FSWs and their partners. Because mid-age FSWs with primary school education or no education were more likely to engage in unprotected sex, interventions should be tailored to meet their needs.

At the alter level, consistent condom use was highly associated with their relationships to egos. Consistent condom use was much lower for spousal ties than other ties. Requesting consistent condom use may raise suspicions on marital faithfulness. Sex work in China is illegal and culturally unaccepted by the Chinese society. Consequently, not only sex workers, but their families and close associates are severely stigmatized. In order to keep their family dignity and avoid harm to their marriages, mid-age FSWs usually conceal their sex worker identity. The majority (80%) of mid-age FSWs in this study did not disclose their sex work job to their husbands. Although consistent condom use was relatively higher over other ties (i.e., ties with clients, boyfriends, and others) compared to spousal relationships, its use was only between 32–65%. Such low condom use may facilitate HIV/STI transmission not only among spousal ties, but other ties as well. In the long run, marital damage and instability of family would occur among mid-age FSWs if their faithful husbands and boyfriends became infected with STIs.

The relationship between social support and condom use is complex and against our initial hypothesis. On the one hand, condoms were not consistently used over the sex ties with strong social support and trusted relations. That is, condoms are more likely to be used with weak ties, rather than strong ties. To maintain social support and a better relationship, mid-age FSWs may not request condom use with those who provide stronger social support. Similarly, alters who provide a higher level of support may not want to use condoms, especially when they have sex with husbands and boyfriends.

As pointed out by Latkin and Knowlton,13 the same network alters who provide support and who are sources of conflict may simultaneously impede certain health outcomes. A similar negative association was reported in studies among heterosexual men, as well as among men who have sex with men, and men who have sex with both men and women in the US.43,64 On the other hand, preferable attitudes toward condom use may modify the association between emotional support and condom use. Under this interaction scenario, condoms are more likely to be used when ego has better attitudes towards condom use and alters provide stronger emotional support. However, condoms are less likely to be consistently used when ego does not have strong favorable attitudes, even when they receive stronger emotional support.

According to the Chinese collectivist culture,65,66 emotional support is more substantial than tangible support to convey a sense of belonging, esteem, value and respect. They may ask for material support from others, but share their sensitive feelings and private behavior with trusted peers only and seek emotional support from them. This may explain why the association between tangible support and condom use was not substantial. The findings indicate interventions targeting safer sex should change mid-age FSWs' attitudes toward condom use and increase social support within their sexual networks.

The finding of lower consistent condom use among mid-age age FSWs in Qingdao compared to mid-age FSWs in Nanning was not expected as Qingdao is located in the area with lower prevalence of HIV/STIs and Nanning in one of the most HIV/STIs stricken areas, according to the China National HIV/STI Surveillance.4,67 After further analyzing the data, we found that more mid-age FSWs in Qingdao engaged in unprotected sex and had a larger number of clients and a lower HIV/STI knowledge score compared to mid-age FSWs in Nanning. Because Nanning is located in the most HIV-affected area in China, many HIV/STD intervention activities have been conducted there, which may have promoted condom use. These findings imply that the Chinese health authorities need to pay attention to implementing intervention programs not only in geographic areas with higher HIV/STI epidemics, but also in areas with small-scale epidemics.49

There are some limitations in this study. First, the cross-sectional nature of the survey does not allow us to identify casual relationships because of potential temporal ambiguity bias. Second, the results may not be generalizable to the broader population of mid-age FSWs and their supporting partner as it was conducted only in three areas in China. Third, the reliance on self-reports of condom use over the ego–alter ties could be biased due to social desirability bias. Fourth, we assumed no overlap between the alters of one ego and the alters of other egos to analyze egocentric network data using multilevel models,63 which appears to be a strong assumption. It is reasonable that there was very minimal overlap of the alters from different egos in our data due to the nature of sex work (stigma and concealment of sex work identity). Finally, one important network component, network norms regarding condom use, were not measured and consequently not analyzed in this study.

Given the low frequency of condom use, future interventions should focus on mid-age FSWs and their sexual partners within and beyond their support networks. These multilevel influences on condom use reinforce that behavioral interventions should be driven by social network theory or the social ecological model, incorporate multiple network levels of influence, and should not focus exclusively on individual level characteristics. The interactive effect of social support at the alter level and attitudes toward condom use at the ego level suggests that interventions need to capitalize on the range of social network relations beyond commercial clients, such as husbands, friends, and other social network members to change the attitudes of mid-age FSWs.

As condoms are more likely to be used over weak ties than strong ties, interventions should target both ties so that behavioral changes can be sustained. Because it is impractical to promote condom use within spousal ties because of the stigma associated with sex work and the potential for marital conflict, combined intervention programs with both behavioral and biomedical components should be designed, which include early diagnosis and treatment of STIs, immediate medical care, promotion of safer sex, and the provision of social support.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff from Shandong University School of Public Health, Nanning Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Hefei Center for Diseases Control and Prevention, and Qingdao Center for Disease Control and Prevention for their participation in the study, and to all the participants who willingly gave their time to provide the study data.

This work was supported by a research grant (R01HD068305) from National institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, the decision to publish or preparation of the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection among adults aged 50 years and older in the United States and dependent areas, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2013;18: Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2010_hiv_surveillance_report_vol_18_no_3.pdf Published February 2013. (Last accessed February13, 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 2.High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB, et al. HIV and aging: State of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60:S1–S18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H, Lin X, Xu Y, Chen S, Shi J, Morisky D. Emerging HIV epidemic among older adults in Nanning, China. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:565–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xing J, Li YG, Tang W, et al. HIV/AIDS epidemic among older adults in China during 2005–2012: Results from trend and spatial analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e53–e60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou C, Rou K, Dong WM, et al. High prevalence of HIV and syphilis and associated factors among low-fee female sex workers in mainland China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao C, Liu H, Sherman S, et al. Typology of older female sex workers and sexual risks for HIV infection in China: A qualitative study. Cult Health Sex 2014;16:47–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Y, Henderson GE, Pan S, Cohen MS. HIV/AIDS risk among brothel-based female sex workers in China: Assessing the terms, content, and knowledge of sex work. Sex Transm Dis 2004;31:695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y, Muessig KE, Zhang N, Maman S. Unpacking the 'structural' in a structural approach for HIV prevention among female sex workers: A case study from China. Glob Public Health 2015;10:852–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen Z, Zhang C, Li X, et al. HIV-related behavioral risk factors among older female sex workers in Guangxi, China. AIDS Care 2014;26:1407–1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remis RS, Kang L, Calzavara L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection and sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers (FSWs) in Shanghai, China. Epidemiol Infect 2015;143:258–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z, Su J, Peng X, Wu N. A decline in HIV and syphilis epidemics in Chinese female sex workers (2000–2011): A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e82451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weir SS, Li J, Edwards JK, et al. Exploring venue-associated risk: A comparison of multiple partnerships and syphilis infection among women working at entertainment and service venues. AIDS Behav 2014;18:S153–S160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Social network assessments and interventions for health behavior change: A critical review. Behav Med 2015;41:90–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson BT, Redding CA, DiClemente RJ, et al. A network-individual-resource model for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav 2010;14:204–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neaigus A, Friedman SR, Curtis R, et al. The relevance of drug injectors' social and risk networks for understanding and preventing HIV infection. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris M, Zavisca J, Dean L. Social and sexual networks: Their role in the spread of HIV/AIDS among young gay men. AIDS Educ Prev 1995;7:24–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman SR, Curtis R, Neaigus A, Jose B, Des Jarlais DC. Social Networks, Drug Injectors' Lives, and HIV/AIDS: Dordrecht, Netherlands; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothenberg RB, Potterat JJ, Woodhouse DE, Muth SQ, Darrow WW, Klovdahl AS. Social network dynamics and HIV transmission. AIDS 1998;12:1529–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Liu H, Luo J, Koram N, Detels R. Sexual transmissibility of HIV among opiate users with concurrent sexual partnerships: An egocentric network study in Yunnan, China. Addiction 2011;106:1780–1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsden PV, Friedkin N. Network studies of social influence. In: Wasserman S, Galaskiewicz J, eds. Advances in Social Network Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994:3–25 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Triandis C. Individualism and collectivsm. In: Ricky D, ed. Handbook of Culture and Pscyhology. Cary, NC: Oxford University, 2001:35–50 [Google Scholar]

- 22.King AYC, Bond MH. The confusian paradigm of Man: A sociological view. In: Tseng W, Wu DH, eds. Chinese Culture and Mental Health. New York: Academic Press, 1985:29–46 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu GZ. Chinese culture and disability information for U.S. Service Providers. New York: CIRRIE, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui CH, Triandis HC. Individualism-collectivism: A study of cross-cultural researchers. J Cross Cult Psychol 1986;17:225–248 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Triandis HC, Bontempo R, Villareal MJ, Asai M, Lucca N. Individualism and collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives on selfngroup relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:323–338 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray-Johnson L, Witte K, Liu W-Y, Hubbell AP, Sampson J, Morrison K. Addressing cultural orientation in fear appeals: Promoting AIDS-protective behaviors among Mexican immigrant and African American adolescents and American and Taiwanese college students. J Health Commun 2001;6:335–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips M, Pearson V. Coping in Chinese Communities: The need for a new research agenda. In: Bond M, ed. Chinese Psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1996:429–440 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Triandis HC. Self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychol Rev 1989;96:269–289 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider JA, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, et al. Network mixing and network influences most linked to HIV infection and risk behavior in the HIV epidemic among black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e28–e36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latkin CA, Donnell D, Metzger D, et al. The efficacy of a network intervention to reduce HIV risk behaviors among drug users and risk partners in Chiang Mai, Thailand and Philadelphia, USA. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:740–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujimoto K, Wang P, Ross MW, Williams ML. Venue-mediated weak ties in multiplex HIV transmission risk networks among drug-using male sex workers and associates. Am J Public Health 2015;105:1128–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han L, Zhou C, Li Z, et al. Differences in risk behaviours and HIV/STI prevalence between low-fee and medium-fee female sex workers in three provinces in China. Sex Transm Infect 2015. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, Kennedy M, Liu H, Hong F, Ha T, Ning Z. Mediation effect of perceived behavioural control on intended condom use: Applicability of the theory of planned behaviour to money boys in China. Sex Health 2013;10:487–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu J, Lau JT, Chen X, et al. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to investigate condom use behaviors among female injecting drug users who are also sex workers in China. AIDS Care 2009;21:967–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maughan-Brown B, Kenyon C, Lurie MN. Partner age differences and concurrency in South Africa: Implications for HIV-infection risk among young women. AIDS Behav 2014;18:2469–2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drame FM, Foley EE. HIV/AIDS in mid-sized cities in Senegal: From individual to place-based vulnerability. Soc Sci Med 2015;133:296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwiatkowski CF, Booth RE. Differences in HIV risk behaviors among women who exchange sex for drugs, money, or both drugs and money. AIDS Behav 2000;4:233–240 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan SY, Melendez-Torres GJ. A systematic review and metasynthesis of barriers and facilitators to negotiating consistent condom use among sex workers in Asia. Cult Health Sex 2016;18:249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van den Boom W, Stolte IG, Roggen A, Sandfort T, Prins M, Davidovich U. Is anyone around me using condoms? Site-specific condom-use norms and their potential impact on condomless sex across various gay venues and websites in The Netherlands. Health Psychol 2015;34:857–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedman SR, Aral S. Social networks, risk-potential networks, health, and disease. J Urban Health 2001;78:411–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snijders T, Spreen M, Zwaagstra R. The use of multilevel modeling for analysing personal networks: networks of cocaine users in an urban area. J Quantit Anthrop 1995;5:85–105 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deutsch AR, Steinley D, Slutske WS. The role of gender and friends' gender on peer socialization of adolescent drinking: A prospective multilevel social network analysis. J Youth Adolesc 2014;43:1421–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennedy DP, Wenzel SL, Brown R, Tucker JS, Golinelli D. Unprotected sex among heterosexually active homeless men: Results from a multi-level dyadic analysis. AIDS Behav 2013;17:1655–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lukena VdM, Tranmerb M. Personal support networks of immigrants to Spain: A multilevel analysis. Soc Netw 2010;32:253–262 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perry BL, Pescosolido BA. Social network activation: The role of health discussion partners in recovery from mental illness. Soc Sci Med 2015;125:116–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50:179–211 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zang C, Guida J, Sun Y, Liu H. Collectivism culture, HIV stigma and social network support in Anhui, China: A path analytic model. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014;28:452–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hao C, Guida J, Morisky D, Liu H. Family network, workplace network, and their influence on condom use: A qualitative study among older female sex workers in China. J Sex Res 2015;52:924–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu H, Morisky DE, Lin X, Ma E, Jiang B, Yin Y. Bias in self-reported condom use: Association between over-reported condom use and syphilis in a three-site study in China. AIDS Behav 2015. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. 2012 China AIDS response progress report. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/ce_CN_Narrative_Report[1].pdf (Last accessed February13, 2016)

- 51.Heckathorn DD. Extensions of respondent-driven sampling: Analyzing continuous variables and controlling for differential recruitment. Sociol Methodol 2007;37:151–208 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu H, Li J, Ha T, Li J. Assessment of random recruitment assumption in respondent-driven sampling in egocentric network data. Soc Netw 2012;1:13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gile KJ, Johnston LG, Salganik MJ. Diagnostics for respondent-driven sampling. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2015;178:241–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Handcock MS, Fellows IE, Gile KJ. RDS Analyst: Software for the Analysis of Respondent-Driven Sampling Data, Version 0.42, Available at: http://hpmrg.org (Last accessed August20, 2015)

- 55.Hintze JL. PASS 13–Power Analysis and Sample Size; User's Guide. Kaysville, Utah: NCSS, Available at: www.ncss.com (Last accessed August20, 2015)

- 56.Chen XS, Wang QQ, Yin YP, et al. Prevalence of syphilis infection in different tiers of female sex workers in China: Implications for surveillance and interventions. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin CC, Gao X, Chen XS, Chen Q, Cohen MS. China's syphilis epidemic: A systematic review of seroprevalence studies. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:726–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu H, Feng T, Liu H, et al. Egocentric networks of Chinese men who have sex with men: Network components, condom use norms and safer sex. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009;23:885–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koram N, Liu H, Li J, Luo J, Nield J. Role of social network dimensions in the transition to injection drug use: Actions speak louder than words. AIDS Behav 2011;15:1579–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Norbeck JS. The Norbeck social support questionnaire. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 1984;20:45–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hobbs MM, Steiner MJ, Rich KD, et al. Good performance of rapid prostate-specific antigen test for detection of semen exposure in women: Implications for qualitative research. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:501–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abacus Diagnostics I. ABAcard P30 test for the forensic identification of semen at crime scence: Manufacturers' Instruction. 2006

- 63.Crossley N, Elisa. B, Edwards G, Everett MG, Koskinen J, Tranmer M. Social Network Analysis for Ego-Nets. London: SAGE, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Latkin C, Yang C, Tobin K, Penniman T, Patterson J, Spikes P. Differences in the social networks of African American men who have sex with men only and those who have sex with men and women. Am J Public Health 2011;101:e18–e23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu H, Li J, Lu Z, Liu W, Zhang Z. Does Chinese culture influence psychosocial factors for heroin use among young adolescents in China? A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Triandis C. Individualism-Collectivism and personality. J Personal 2001;69:907–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang L, Tang W, Wang L, et al. The HIV, syphilis, and HCV epidemics among female sex workers in China: Results from a serial cross-sectional study between 2008 and 2012. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e1–e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]