Abstract

Objective. To investigate the effect of an interprofessional service-learning course on health professions students’ self-assessment of Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) competencies.

Design. The semester-long elective course consisted of two components: a service component where students provided patient care in an interprofessional student-run free clinic and bi-weekly workshops in which students reflected on their experiences and discussed roles, team dynamics, communication skills, and challenges with underserved patient populations.

Assessment. All fifteen students enrolled in the course completed a validated 42-question survey in a retrospective post-then-pre design. The survey instrument assessed IPEC competencies in four domains: Values and Ethics, Roles and Responsibilities, Interprofessional Communication, and Teams and Teamwork. Students’ self-assessment of IPEC competencies significantly improved in all four domains after completion of the course.

Conclusion. Completing an interprofessional service-learning course had a positive effect on students’ self-assessment of interprofessional competencies, suggesting service-learning is an effective pedagogical platform for interprofessional education.

Keywords: interprofessional education, service-learning, student-run free clinic, surveys, interprofessional competencies

INTRODUCTION

In an increasingly complex health care environment, collaborative models of care that feature teams of health professionals are essential to providing high quality patient care.1-3 To create a collaborative practice-ready workforce, health professions educators must help students develop the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors to function effectively in team-based care models. Interprofessional education (IPE) is a means to teach and evaluate students on these abilities.1 However, learning in an interprofessional group is not the same thing as functioning interprofessionally.4 To prepare students to function on an interprofessional team after graduation, IPE must include interprofessional student groups working together in real-life situations.

In response to the need for IPE, education associations from dentistry, medicine, nursing, osteopathic medicine, pharmacy, and public health formed the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC). They developed 38 competencies for interprofessional practice in four domains: Values and Ethics, Roles and Responsibilities, Interprofessional Communication, and Teams and Teamwork.5 As interprofessional competencies are incorporated into accreditation standards for health professions educational programs,6-8 academic institutions will need to identify effective means of addressing those competencies in their curricula. One method for students to learn to function interprofessionally in real-life situations is through service-learning. Service-learning is defined as “a structured learning experience which combines community service with preparation and reflection.”9

At The Ohio State University (OSU), a service-learning course was created to: (1) use experiential strategies characterized by student participation in an organized service activity; (2) engage in service that meets identified community needs; (3) connect service to specific learning outcomes; and (4) provide structured time for students to analyze and connect the service experience to learning.10 This service-learning framework allows students from different professions to function as an interprofessional team and gain experience providing care to real patients in the community. The framework also provides the structure for students to reflect on how these activities relate to their learning.

Few published studies examine outcomes related to competencies for an interprofessional service-learning activity,11,12 and no studies evaluating interprofessional competencies in service-learning involve students caring for patients in interprofessional teams. The purpose of this pilot study was to investigate the effectiveness of an interprofessional service-learning elective course involving patient care in underserved populations for improving health professions students’ self-assessment of interprofessional competencies.

DESIGN

The interprofessional service-learning course was created with dual goals of preparing students to practice interprofessionally and to improve the collaboration between professions at a student-run free clinic. An interprofessional team of faculty members from pharmacy, nursing, and social work applied for and received a grant to develop an elective course in their respective programs. One member from each profession participated in the Course Development Institute offered by the University Center for the Advancement of Teaching at OSU.

All students from nursing, social work, and pharmacy who previously committed to volunteering at the free clinic were offered the opportunity to participate in the course. In spring 2014, the first offering of this 2-credit course included seven undergraduate nursing students, two social work students, and six graduate professional pharmacy students. All students enrolled in the course had exposure to clinical settings in their curriculum prior to entering the course with the exception of one undergraduate social work student.

The course consisted of two components: (1) a service component where students provided patient care in an IP student-run free clinic; and (2) workshops in which students reflected on their experiences and discussed roles, team dynamics, communication skills, and challenges with underserved patient populations. Course goals included addressing IPEC competency domains,5 understanding social determinants of health and caring for underserved patient populations, and developing skills to become reflective practitioners.

The semester-long elective course required students to volunteer at the Columbus Free Clinic one evening each month (roughly 20 hours over the semester). Students were involved in all aspects of the clinic, which provides acute and primary medical care, a variety of laboratory services, and prescription medications at no cost to underserved patients of central Ohio. The free clinic volunteer experience consisted of students practicing within their own professional roles on the interprofessional patient care team. For example, pharmacy students worked with providers to make medication recommendations, prepare prescriptions, and counsel patients on their medications.

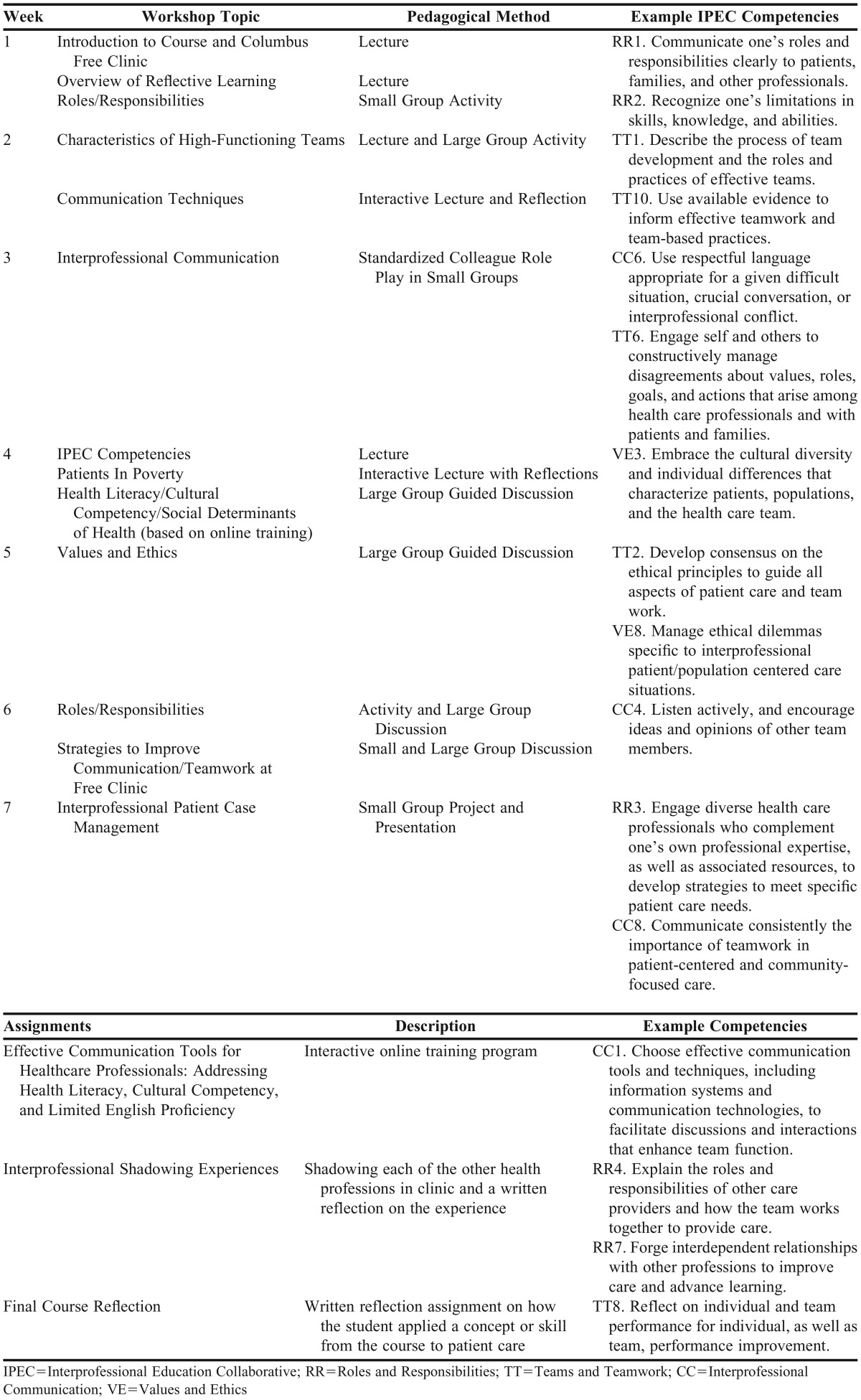

The other course component consisted of students participating in seven 2-hour workshops along with several out-of-class assignments. Course content, pedagogical methods, and example competencies are illustrated in Table 1. The workshop was planned as an evening class every other week to accommodate student schedules. Workshop structure generally involved small interprofessional groups of 3-4 students discussing course content and how it related to their practice experiences. Other activities included a standardized colleague role-play activity, in which student groups rotated through stations to practice communication skills with volunteers acting as different health professionals.

Table 1.

Interprofessional Teamwork in Underserved Patient Care Course Content – Workshop Activities, Course Assignments and Examples of Associated IPEC Competencies

Faculty members, including at least one representative from each profession, delivered content and served as facilitators for student discussion. Students were also required to shadow each of the other health professions in the clinic (medicine, pharmacy, nursing, and social work) and write a reflection on that experience. Students were asked to identify links between their clinic experiences and course content through discussions and reflective activities at each workshop.

During the last class of the semester (April 2014), students completed a previously validated, 42-question survey13 in a retrospective post-then-pre design (eg, at the conclusion of the course, students assessed themselves on each competency and reflected back to assess their proficiency in each competency prior to participating in the course). The survey instrument collected demographic and previous interprofessional experience and assessed IPEC competencies in the four domains.5 Domain-specific scores were created by averaging all competencies within the domain. A paired t test was used to compare differences in posttest and retrospective pretest scores to determine if students’ self-assessment of competencies changed over time. All analyses were conducted in SAS, v9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University deemed this study exempt prior to initiation of the course.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

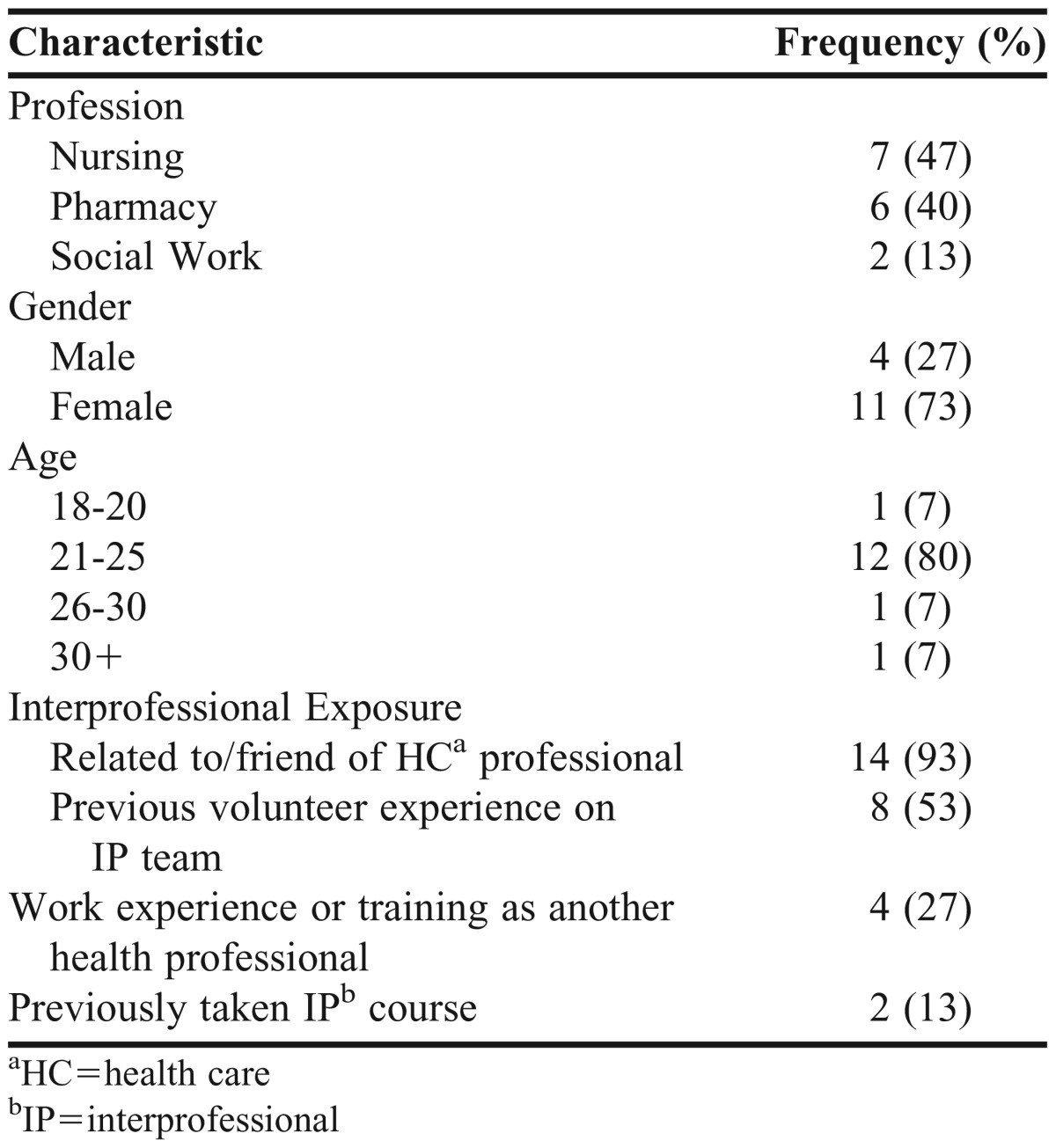

All fifteen students enrolled in the course agreed to participate in the study (100% response rate). Demographics are presented in Table 2. Fifty-three percent had some volunteer experience with an interprofessional team prior to the class. Four students (27%) reported having work experience or training as another health professional and two (13%) had taken an interprofessional course prior to enrolling in this class.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Student Participants in Interprofessional Service-Learning Course

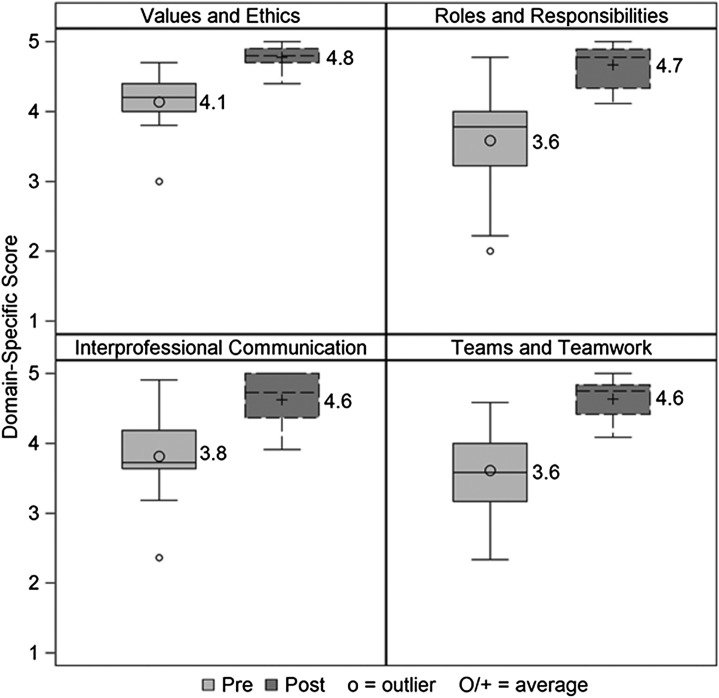

Domain-specific scores could range from one to five, with one indicating strong disagreement and five indicating strong agreement with achievement of the IPEC competency. Overall mean scores for the students’ retrospective pre-assessment ranged from 3.59 for Roles and Responsibilities to 4.14 for Values and Ethics. All four domains showed significant improvement from retrospective pre-assessment to postassessment (p<0.0001 for all domains, Figure 1). The biggest change in scores was for the Roles and Responsibilities domain (mean difference from pre to post of 1.1, SD=0.7), followed by Teams and Teamwork domain (mean difference 1.0, SD= 0.5). When comparing students who volunteered with an interprofessional team prior to enrolling in this service-learning course (n=8) with those who did not (n=7), there were no significant differences regarding changes in domain scores.

Figure 1.

Students' retrospective pre/posttest scores by Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) Competency domain after completion of an interprofessional service-learning course. Students rated their achievement of each competency on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses showed significant improvemant in achievement of compentnencies in all four domains (p<0001). Minimum, twenty-fifth percentile, median, mean (labeled), seventy-fifth percentile, and maximum shown.

Course evaluation of the teaching and learning methods also included open-ended midpoint feedback, an end-of-course survey, and a focus group. The midpoint open-ended, formative feedback activity consisted of students anonymously responding to three questions on a notecard: (1) Over the first half of the course, what has helped your learning? (2) What has hindered it? (3) What changes would you suggest to improve your learning?

Instructors identified common themes from these responses. Students reported that they enjoyed having a reflection exercise at the end of class because it helped them to sort out their thoughts and ideas, solidify concepts, and identify the most important things they learned in the class. They also noted that group activities allowed them to hear perspectives from other professions. They reported enjoying the mix between lecture and discussion. Students also stated that the opportunity to practice communication skills with a standardized colleague brought class concepts to life, and the interprofessional shadowing experiences were valuable for learning about other professions’ roles and gave them a more complete view of the health care team. Faculty members considered this feedback in the delivery of the second half of the course and included some adaptions to make planned activities more interactive.

At the end of the semester, students were asked to participate in an anonymous, instructor-designed survey to provide feedback regarding the teaching and learning methods of the course. On the last day of class, consultants from the University Center for the Advancement of Teaching delivered the survey and facilitated a focus group to allow students the opportunity to elaborate on their survey responses. The results of this survey identified the standardized colleague activity, the communication lecture and discussion, and the interprofessional shadowing experiences as the most useful to students. All 15 students responded that they would recommend the course to a friend.

Center consultants identified themes from the focus group discussion that represented class consensus. In general, the students agreed that role play activities were helpful in allowing them to apply concepts and skills and receive immediate feedback. They also noted that underrepresentation of some relevant professions in the course (social work and medicine) hindered their learning. Students suggested several improvements, including changing the grade scheme from pass/fail to graded, front loading the in-class activities so students have more time to apply skills in their volunteering activities, and shifting some lectures into active-learning activities.

DISCUSSION

Students’ self-assessment of IPEC competencies significantly improved in all four domains after completion of this interprofessional service-learning course. Many studies investigate other methodologies for preparing students and practitioners for interprofessional collaborative practice, such as simulations, small group or web-based discussions, problem-based case discussions, and more.14 The service-learning structure connected the service experience to learning objectives. Students were required to reflect on their experiences and analyze the effect on their learning. It encouraged students to apply the principles discussed in workshop to patient care, and bring their experiences from clinic to the classroom discussion, closing the learning-practice loop.

Prior to enrolling in this course, about half of the students had previously volunteered with an interprofessional team as a community service experience. When comparing the scores of these students to those who had not previously volunteered, there were no differences in the changes in domain scores. Despite the experience practicing on an interprofessional team, these students’ scores were significantly higher after participation in this course. This may be a result of the service-learning framework for the course, as opposed to the community service structure, which does not explicitly link learning outcomes to the experience. While our study was not powered to detect a difference between these groups, the service-learning structure does enhance the effect on learning compared to providing community service alone.15

Another aspect of the service-learning framework is the mutually beneficial relationship between the learner and the service site. Students are an integral part of the Columbus Free Clinic, making up over half of the workforce. However, prior to the start of this course, the interprofessional interaction was somewhat limited. The course was a means of merging students from different professions into one classroom, which in turn facilitated collaboration at the clinic.

One course activity involved small interprofessional groups brainstorming strategies to improve communication and teamwork at the free clinic. Their ideas were compiled and presented to the free clinic steering committee, several of which have been piloted or implemented to improve clinic processes. One example is a patient checklist that follows the patient to let all providers know which services the patient has received and from whom. This checklist facilitates communication between the different professions, improving efficiency and decreasing the patients’ wait time. The success of this activity demonstrates the students’ ability to apply concepts from the course to practice in the clinic. It also demonstrates the value of such a course to the community clinic partner.

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of a course associated with a student-run free clinic at one university. The course content focused on IPEC competencies and would therefore be easily adaptable to other institutions and service-practice settings. Certain core competencies could be emphasized over others depending on an institution’s health professions curricula. The biggest change from retrospective pretest to posttest was in the Roles and Responsibilities domain, with the Teams and Teamwork domain being close behind. It could be that the changes in these domains were greater than the other two domains because these competencies are not explicitly taught in many of the uni-professional curricula. Students’ pretest scores in these domains (Roles and Responsibilities 3.59 and Teams and Teamwork 3.61) were lower compared to the other two domains (Values and Ethics 4.14 and Interprofessional Communication 3.81).

Conversely, ethics and communication are commonly taught across all health professions. The students were likely trained in these topics prior to enrolling in the course, leaving less room for improvement. Previous studies of IPE interventions demonstrated improvement in students’ understanding of their own and others’ roles, or reported improvements in teamwork skills.14 This is consistent with our findings of greater improvement in the Roles and Responsibilities and Teams and Teamwork domains. The outcomes of this study should be further validated by assessing the effect of similar courses on student IPEC competency attainment.

The small sample size allowed for the implementation of this course as a pilot to explore the interprofessional service-learning model within a free clinic and provided an opportunity to assess outcomes and work out details prior to expansion of the course. In the future, we plan to recruit a more representative sample of students by including more social work and medical students. Should the free clinic expand to include other professions, they would be invited to participate in the course, as well. This model could easily be scaled by including other free clinics or opportunities to work on an interprofessional team. Expansion could occur relatively quickly, which would be useful as schools try to meet new accreditation standards. Many institutions with health professions students have interprofessional free clinics,16 which could be used to offer interprofessional service-learning instruction. The existence of the established interprofessional free clinic and relationships with faculty members from each of the colleges allowed for swift movement from course planning to implementation, taking only seven months from notice of the grant award to the first day of class.

Our study is not without limitations. The retrospective post-then-pre-test design introduced the possibility for recall bias, as well as bias of participants reporting an improvement when there may not have been an actual change. The potential for these biases was offset by the elimination of response shift bias. That is, the design accounted for the changes in learner’s knowledge from the intervention, allowing participants to accurately reflect back on what they did or did not know at the start. Because the course was an elective opportunity for students, there was also the potential for self-selection bias. That is, it is possible that the students’ perceptions of their abilities increased because they had a desire to learn about interprofessional teams, and the same results may not occur with students who do not elect to participate in interprofessional education.

While the instrument used in this study was validated, it did rely on students’ self-assessments. Accreditation standards identify self-assessment as an essential skill for students to ensure continuous professional development and life-long learning.6,8 Previous studies showed poor correlation between teacher evaluations and students’ self-assessments in both pharmacy and nursing education.17-21 However, strategies can improve the quality of student self-assessment, such as developing students’ reflective-thinking process.21

In this course, students received education on the critical self-reflection process and were required to engage in self-reflection at each workshop and through several out-of-class assignments. Students were provided with informal, verbal feedback in the classroom, as well as written feedback on their reflection assignments. Developing critical self-reflection skills should improve students’ insights into their performance and/or competency,21 leading to more accurate self-assessments. Future offerings of the course will incorporate more structured feedback from instructors to provide students with quality, external feedback. This too could lead to a more informed self-assessment.21 Objective measurements for interprofessional skills and abilities should be developed and evaluated in future studies.

SUMMARY

As team-based health care models like patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations become the standard, health professions students need to be prepared to practice collaboratively to provide high-quality, patient-centered care. Health professions are adopting interprofessional competencies into accreditation standards to meet this need. This study showed a positive effect of an interprofessional service-learning course on students’ self-assessment of interprofessional competencies. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of service-learning as a method for preparing students for interprofessional practice. That is, an interprofessional service-learning course can serve to develop students’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors necessary to function in collaborative team-based models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Development of this course was supported by a grant from The Ohio State University Service-Learning Initiative. The authors would like to acknowledge Kate Gawlik, MS, Lisa Durham, MSW, LISW-S, and Jennifer Flavin, PharmD for their contributions to course development and delivery and Maria Pruchnicki, PharmD, BCPS, BCACP, CLS for her contributions to the final manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Stephanie Cook, DO, and the steering committee of the Columbus Free Clinic for their support.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization Department of Human Resources for Health. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. 2010. [PubMed]

- 2.Greiner AC, Knebel E. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cuff PA. Insitute of Medicine. Interprofessional Education for Collaboration: Learning How to Improve Health from Interprofessional Models Across the Continuum of Education to Practice. Workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed]

- 5.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Draft Standards 2016.

- 7.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school: standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the MD degree. 2013.

- 8.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Connors K, Seifer S, Sebastian J, Cora-Bramble DE, Hart R. Interdisciplinary collaboration in service-learning: lessons from the health professions. Michigan J Comm Serv Learn. 1995;3(1):113–127. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office of Service-Learning. About service-learning courses. http://service-learning.osu.edu/about-service-learning-courses.html. Accessed May 8, 2014.

- 11.Buff SM, Gibbs PY, Oubre OL, Ariail JC, Blue AV, Greenberg RS. Junior Doctors of Health©: an interprofessional service-learning project addressing childhood obesity and encouraging health care career choices. J Allied Health. 2011;40(3):e39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hope JM, Lugassy D, Meyer R, et al. Bringing interdisciplinary and multicultural team building to health care education: The downstate team-building initiative. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):74–83. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200501000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dow AW, DiazGranados D, Mazmanian PE, Retchin SM. An exploratory study of an assessment tool derived from the competencies of the interprofessional education collaborative. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(4):299–304. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.891573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson R, Bialocerkowski A. Interprofessional education in allied health: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2014;48(3):236–246. doi: 10.1111/medu.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astin A, Vogelgesang L, Ikeda E, Yee J. University of California; Los Angeles: 2000. How service learning affects students. Higher Education Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson SA, Long JA. Medical student-run health clinics: Important contributors to patient care and medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):352–356. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin Z, Gregory PA. Evaluating the accuracy of pharmacy students' self-assessment skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5):Article 89. doi: 10.5688/aj710589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundquist LM, Shogbon AO, Momary KM, Rogers HK. A comparison of students' self-assessments with faculty evaluations of their communication skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(4):Article 72. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mort JR, Hansen DJ. First-year pharmacy students’ self-assessment of communication skills and the impact of video review. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(5):Article 78. doi: 10.5688/aj740578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watts WE, Rush K, Wright M. Evaluating first-year nursing students’ ability to self-assess psychomotor skills using videotape. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2009;30(4):214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motycka CA, Rose RL, Ried LD, Brazeau G. Self-assessment in pharmacy and health science education and professional practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(5):Article 85. doi: 10.5688/aj740585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]