Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness and tolerability of a dietary supplement with a combination of omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants on dry eye symptoms caused by chronic instillation of antihypertensive eye drops in patients with glaucoma.

Patients and methods

A total of 1,255 patients with glaucoma and dry eye symptoms related to antiglaucoma topical medication participated in an open-label, uncontrolled, prospective, and multicenter study and were instructed to take three capsules a day of the nutraceutical formulation (Brudypio® 1.5 g) for 12 weeks. Dry eye symptoms (graded as 0–3 [none to severe, respectively]), conjunctival hyperemia, tear breakup time, Schirmer I test, Oxford grading scheme, and intraocular pressure were assessed.

Results

After 12 weeks of administration of the dietary supplement, all dry eye symptoms improved significantly (P<0.001) (mean 1.3 vs 0.6 for scratching, 1.4 vs 0.7 for stinging sensation, 1.6 vs 0.7 for grittiness, 1.0 vs 0.4 for tired eyes, 1.1 vs 0.5 for grating sensation, and 0.8 vs 0.3 for blurry vision). The Schirmer test scores and the tear breakup time also increased significantly. There was an increase in the percentage of patients grading 0–I in the Oxford scale and a decrease in those grading IV–V. Compliance was recorded in 62.5% of patients. In compliant patients, the mean differences at 12 weeks vs baseline of dry eye symptoms were statistically significant as compared to noncompliant patients.

Conclusion

Dietary supplementation with Brudypio® may be a clinically valuable additional option for the treatment of dry eye syndrome in patients with glaucoma using antiglaucoma eye drops. These results require confirmation with an appropriately designed randomized controlled study.

Keywords: antioxidants, dry eye symptoms, nutraceutics, omega-3, polyunsaturated fatty acids

Introduction

Patients with glaucoma frequently suffer from some degree of ocular surface dysfunction secondary to the long-term instillation of topical antihypertensive eye drops. Dry eye syndrome is a multifactorial disease associated with inadequate tear film volume, tear film instability, and ocular surface damage.1–4 It is accompanied by an increased osmolarity of tear film and the inflammation of ocular surface. The symptoms of ocular surface disease may include dryness, burning or stinging, itching, irritation, tearing, photophobia, redness, fatigue, fluctuating visual acuity, and blurred vision.5 Also, there is a poor relationship between dry eye signs and symptoms.6 These visual disturbances and discomforts often compromise compliance with intraocular pressure (IOP)-lowering medications and impair the quality of life of the patients as well as their physical, social, and psychological functioning.7,8 Ocular surface dysfunction is a common morbidity in patients with glaucoma, in part due to the fact that its prevalence, as in glaucoma, increases with age. Symptoms and signs of the dry eye syndrome are observed in ~15% of the elderly population and are reported in 48%–59% of medically treated patients with glaucoma.9–12 Baudouin et al13 reported that moderate or severe ocular dysfunction syndrome was found in 63% of patients with severe glaucoma and in 41% of those with mild glaucoma, with severity directly related to IOP. One of the six patients with glaucoma presented the symptoms of dry eye syndrome severe enough to need some form of treatment.14 However, the diagnosis of ocular surface dysfunction in patients with glaucoma is frequently overlooked since the focus of management is mainly on the evaluation of IOP and the markers of glaucomatous disease progression. On the other hand, a significant proportion of dry eye population has a coexisting glaucoma, and in these patients, chronic topical therapy with antihypertensive eye drops can lead to ocular discomfort. In a retrospective study of 190 patients aged 45 years or older seen at the Ocular Surface Disease and Dry Eye Clinic in Baltimore, MD, USA, 11% were found to have coexisting glaucoma.15 Dry eye type was predominantly characterized by a combined evaporative and aqueous tear deficiency (86% of patients).

Treatment of the dry eye syndrome is mainly directed to reduce the symptoms, usually by the application of artificial tears.2,16,17 Also, artificial tear administration in patients with glaucoma with dry eyes avoids improper confirmation of visual field progression.18 On the other hand, inflammation and oxidative stress may play a key role in the development of dry eye syndrome.13,19,20 Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation has been shown to potentiate the antioxidant defenses, to relieve the bothering symptoms and signs of eye dryness by improving the lubrication and tear stability, and to reduce the ocular surface inflammation in patients with glaucoma,21 in patients with pure dry eye,22–24 in patients suffering from meibomian gland dysfunction,25,26 and in patients after photoreactive keratectomy.27

The present open-label intervention study carried out in a large sample of patients with glaucoma was designed to assess the effectiveness and tolerability of oral supplementation with a combination of omega-3 essential fatty acids and antioxidants in dry eye-related symptoms derived from chronic instillation of topical eye hypotensive drugs.

Materials and methods

This was an open-label, intervention, noncomparative, prospective, multicenter study carried out during the routine ophthalmological appointments in the conditions of daily practice. The objective of the study was to assess the effectiveness of an oral nutraceutical formulation based on omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants in the relief of dry eye and conjunctival irritation symptoms secondary to the use of antihypertensive eye drops in patients with chronic glaucoma. The tolerability of the oral nutraceutical formulation was also evaluated. The duration of the study was 12 weeks.

Patients of any age and sex who were, otherwise healthy, diagnosed with chronic glaucoma and treated with topical antiglaucoma medications were eligible to participate in the study during a routine ophthalmological examination when the reason for consultation was poor tolerance to antihypertensive eye drops due to associated signs and symptoms of dry eye syndrome and conjunctival hyperemia. Dry eye symptoms included painful eyes, tired eyes, blurry vision, stinging sensation, and eye irritation. The intensity of eye complaints was sufficiently important to be the reason for consultation. Eligibility criteria also included users and nonusers of artificial tears. Patients with fish allergy, atopy, history of allergic disorders, and history of bariatric surgery for morbid obesity, pregnant women, and patients currently treated with vitamins or any other dietary supplements were excluded from the study, as were those deemed unable to participate in the study according to the clinician’s criteria. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for the protection of human subjects, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethics approval was not sought as the product was not a drug but a food supplement, and the study has been performed in routine daily practice.

A total of 65 ophthalmologists all over Spain were invited to participate voluntarily in the study by the sales division of the pharmaceutical company who manufactures the supplement (Brudypio® 1.5 g; Brudy Laboratories, Barcelona, Spain). The composition of the supplement formulation is shown in Table 1. This is a concentrated DHA triglyceride having a high antioxidant activity, patented to prevent cellular oxidative damage.28 The products were provided to the investigators by Brudy Laboratories. Between September 1, 2013, and December 31, 2013, eligible patients who gave written informed consent to take part in the study were recruited by the participating ophthalmologists, with a total of 20 patients per clinician.

Table 1.

Composition of Brudypio® 1.5 g

| Composition | Per capsule | Percentage of recommended amount in one capsule | Per three capsules | Percentage of recommended amount in three capsules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrated oil in omega-3 fatty acids (mg) | 500 | 1,500 | ||

| TG-DHA 70% | 350 | – | 1,050 | – |

| EPA 8.5% | 42.5 | – | 127.5 | – |

| DPA 6% | 30 | – | 90 | – |

| Vitamins | ||||

| Vitamin A (retinol, μg) | 133.3 | 17 | 400 | 50 |

| Vitamin C (ascorbic acid, mg) | 26.7 | 33 | 80 | 100 |

| Vitamin E (d-α-tocopherol, mg) | 4 | 33 | 12 | 100 |

| Vitamin B1 (thiamine, mg) | 0.36 | 33 | 1.1 | 100 |

| Vitamin B2 (riboflavin, mg) | 0.46 | 33 | 1.4 | 100 |

| Vitamin B3 (niacin equivalent, mg) | 5.33 | 33 | 16 | 100 |

| Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine, mg) | 0.46 | 33 | 1.4 | 100 |

| Vitamin B9 (folic acid, μg) | 66.7 | 33 | 200 | 100 |

| Vitamin B12 (cobalamin, μg) | 0.83 | 33 | 2.5 | 100 |

| Essential trace elements | ||||

| Zinc (mg) | 3.33 | 33 | 10 | 100 |

| Copper (mg) | 0.33 | 33 | 1 | 100 |

| Manganese (mg) | 0.66 | 33 | 2 | 100 |

| Selenium (μg) | 18.3 | 33 | 55 | 100 |

| Other components | ||||

| Lutein (mg) | 3.33 | – | 10 | – |

| Zeaxanthin (mg) | 0.33 | – | 1 | – |

| Glutathione (mg) | 2 | – | 6 | – |

| Lycopene (mg) | 2 | – | 6 | – |

| Coenzyme Q10 (mg) | 2 | – | 6 | – |

| Anthocyanins (mg) | 5 | – | 15 | – |

| Oleuropein (μg) | 67 | – | 200 | – |

Note: The dosage tested is three capsules per day, which corresponds to 100% of the recommended daily amounts of the included vitamins and minerals.

Abbreviations: TG-DHA, triglyceride-bound docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DPA, docosapentaenoic acid.

Patients were visited at baseline and at the end of the study (12 weeks). At the baseline visit (visit 0), the patient’s eligibility and baseline parameters were assessed, and the nutraceutical formulation was prescribed. The assessed baseline parameters were demographics (age and sex), use of artificial tears and mean daily eye drops, current type of hypotensive eye medication and mean daily eye drops, and dry eye symptoms (categorized as 0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe), including scratchy and stinging sensation in the eyes, grittiness, painful eyes, tired eyes (eye fatigue), grating sensation, blurry vision, and any others. Conjunctival hyperemia was rated as none, mild, moderate, and severe. Tear breakup time (TBUT) was measured by the instillation of one drop of 2% fluorescein. The time until disappearance of the dye was recorded, and the average of three trials was calculated. Tear instability was defined as TBUT <10 seconds. Tear quantification was assessed with the Schirmer I test, which was applied during a 5-minute interval, without anesthesia. The Oxford grading scheme29 was used to estimate surface damage according to the intensity of fluorescein staining, ranging from I to V for each panel (0–I, normal; II–III, mild to moderate; IV–V, severe). Goldman applanation tonometry was used for IOP determination.

At baseline, patients were also instructed to take three capsules of the study medication (Brudypio® 1.5 g). Ophthalmologists were instructed to emphasize the importance of taking the nutraceutical formulation as prescribed in order to help patients improve their compliance and increase the benefit that they may receive from the supplement, as well as to ensure the validity of the final data of the study.

At the end of the study (week 12), data recorded included compliance with treatment: “Did you take the three capsules every day?” (categorized as always, some forgetfulness, and much forgetfulness); “Have you noticed any change in symptoms?” (categorized as yes or no); assessment of dry eye symptoms and conjunctival hyperemia as at baseline visit; mean daily eye drops of artificial tears; results of TBUT test, Oxford grading test, and IOP; tolerability to nutraceutical formulation (categorized as fish-tasting regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and none of the above); level of the patient’s satisfaction (categorized as not at all satisfied, satisfied, and very satisfied); and clinical assessment of the ophthalmologists (categorized as no improvement, mild improvement, and large improvement). Patients could withdraw from the study of their own free will or be removed according to the ophthalmologist’s criteria due to adverse events, concomitant diseases, or any other medical reasons.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (±SD) when distribution was normal or as median and interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) when distribution departed from normality, and categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Differences of continuous variables between the visit 0 (baseline) and the visit at the end of treatment (week 12) were analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired samples. Changes in each individual with dry eye symptoms between the groups of none/mild vs moderate/severe conjunctival hyperemia and between compliant (those who always took the three capsules a day) and noncompliant patients (those who reported some or much forgetfulness) were compared with the Mann–Whitney U-test. The degree of satisfaction with treatment for patients and clinicians between the visit 0 and the visit at 12 weeks were compared with the chi-square test. Statistical analyses were performed with the R Project for Statistical Computing (R 3.0) program (http://www.r-project.org). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

None of the 65 ophthalmologists invited to take part in the study declined participation. The number of patients recruited by each ophthalmologist ranged between ten and 20. A total of 1,290 patients with chronic glaucoma and dry eye symptoms related to topical use of hypotensive eye drops were recruited for the study. However, 35 patients (2.7%) were not included in the analysis due to missing data in the final visit at 12 weeks regarding whether or not they had been taking the three capsules a day of the nutraceutical supplement. Therefore, the study population included 1,255 patients, who visited at baseline and at 12 weeks. Sixty-two percent were women, with a mean (SD) age of 63.6 (12.8) years (range 18–97). All patients used hypotensive eye drops, with a large variety of fixed and unfixed combinations and a mean (SD) eye drops instillation of 1.7 (2.0) (range 1–32) per day. Also, 88.3% of the patients used artificial tears to relieve dry eye symptoms, with a daily mean (SD) of 3.4 (1.6) instillations of eye drops. The mean intensity of dry eye symptoms varied from 0.7 (0.8) for painful eyes to 1.6 (0.8) for grittiness. Conjunctival hyperemia was mild in 48.8% of the patients and moderate in 33.5% of the patients. Results of the Schirmer test, TBUT, Oxford grading scale, and IOP are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of variables at baseline (visit 0) and at 12 weeks in 1,255 patients with glaucoma with dry eye symptoms

| Variables | Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men (%) | 477 (38.0%) | ||

| Women (%) | 778 (62.0%) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) (years) | 63.6 (12.8) | ||

| Hypotensive medication, daily eye drops, mean (SD) | 1.7 (2.0) | ||

| Artificial tears’ users, n (%) | 959 (88.3) | ||

| Daily eye drops, mean (SD) | 3.4 (1.6) | ||

|

|

|||

| Baseline(visit 0) | Visit at 12 weeks | P-value | |

|

|

|||

| Dry eye symptoms, mean (SD) | |||

| Scratchy | 1.3 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Stinging sensation | 1.4 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Grittiness | 1.6 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Painful eyes | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Tired eyes | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Grating sensation | 1.1 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Blurry vision | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Conjunctival hyperemia, n (%) | |||

| None | 106 (9.2) | 335 (31.6) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 561 (48.8) | 615 (58.0) | |

| Moderate | 385 (33.5) | 105 (9.9) | |

| Severe | 98 (8.5) | 8 (0.6) | |

| Oxford grade, n (%) | |||

| Right eye | |||

| 0 | 159 (12.9) | 458 (38.0) | <0.001 |

| I | 466 (37.7) | 543 (45.0) | |

| II | 383 (31.0) | 164 (13.6) | |

| III | 173 (14.0) | 34 (2.8) | |

| IV | 50 (4.1) | 5 (0.4) | |

| V | 6 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Left eye | |||

| 0 | 153 (12.4) | 462 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| I | 472 (38.3) | 530 (44.0) | |

| II | 368 (29.8) | 175 (14.6) | |

| III | 186 (15.1) | 30 (2.5) | |

| IV | 46 (3.7) | 5 (0.4) | |

| V | 10 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Tear breakup time, median (IQR) (seconds) | |||

| Right eye | 8 (6–10) | 10 (8–12) | <0.001 |

| Left eye | 8 (6–10) | 10 (8–12) | <0.001 |

| Schirmer test, mean (SD) (mm) | |||

| Right eye | 9.69 (4.02) | 11.0 (3.70) | <0.001 |

| Left eye | 9.81 (4.06) | 12.1 (18.7) | <0.001 |

| Daily eye drops of artificial tears, mean (SD) | 3.45 (1.62) | 3.40 (1.56) | 0.003 |

| Intraocular pressure, mean (SD) (mmHg) | |||

| Right eye | 16.4 (2.92) | 16.1 (2.70) | <0.001 |

| Left eye | 16.5 (2.95) | 16.1 (2.60) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

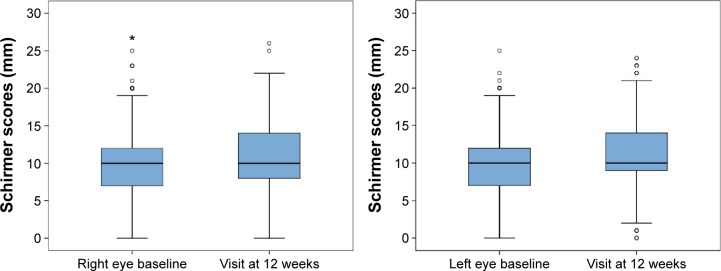

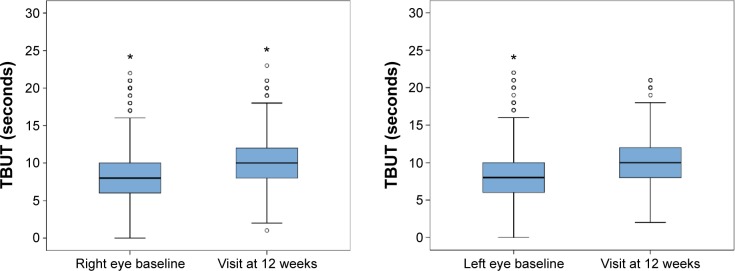

Data recorded at the end of the study (visit at 12 weeks) showed statistically significant improvement in all study variables (P<0.001). As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the Schirmer test scores and the TBUT increased significantly, reflecting improvement in tear secretion and tear film stability. Moreover, there was an increase in the percentage of patients grading 0–I in the Oxford scale and a decrease in those grading IV–V. A significant difference in IOP values was also observed (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Changes in Schirmer test scores in the right and left eyes at baseline (visit 0) and at visit at 12 weeks (*P<0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Figure 2.

Changes in tear instability, TBUT, in the right and left eyes at baseline (visit 0) and at visit at 12 weeks (*P<0.001, Wilcoxon test).

Abbreviation: TBUT, tear breakup time.

In relation to compliance with treatment, 62.5% of the patients reported having taken the three capsules always, and the remaining 37.4% of the patients reported some or much forgetfulness. Changes of dry eye symptoms according to compliance with omega-3 fatty acids supplementation are shown in Table 3. At the end of treatment (visit at 12 weeks), there were statistically significant mean differences as compared to baseline in all dry eye symptoms in favor of the compliant group except for painful eyes and tired eyes. In addition, among the patients who were compliant with the oral nutraceutical formulation, the degree of improvement of each individual with dry eye symptoms was significantly higher (P<0.001) among those with moderate/severe conjunctival hyperemia than patients with none/mild conjunctival hyperemia (Table 4).

Table 3.

Improvement of dry eye symptoms according to compliance with treatment

| Dry eye symptoms | Baseline (visit 0)

|

Visit at 12 weeks

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complianta | Noncompliantb | Compliant | Noncompliant | ||

| Scratchy | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.2 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.7) | |

| Stinging sensation | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.7) | |

| Grittiness | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.7) | |

| Painful eyes | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | |

| Tired eyes | 1.0 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.6) | |

| Grating sensation | 1.2 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.6) | |

| Blurry vision | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.5) | |

|

|

|||||

| Difference 12 weeks vs baseline | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Compliant | Noncompliant | P-value | |||

|

|

|||||

| Scratchy | −0.7 (0.7) | −0.6 (0.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Stinging sensation | −0.8 (0.7) | −0.7 (0.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Grittiness | −0.9 (0.8) | −0.7 (0.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Painful eyes | −0.4 (0.7) | −0.3 (0.6) | 0.060 | ||

| Tired eyes | −0.6 (0.8) | −0.5 (0.7) | 0.120 | ||

| Grating sensation | −0.7 (0.8) | −0.5 (0.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Blurry vision | −0.5 (0.7) | −0.4 (0.6) | 0.015 | ||

Notes: Data as mean (standard deviation). Compliant (781, 62.2%) and noncompliant (474, 37.8%) are self-reported data.

Compliant: always took the three capsules every day.

Noncompliant: some/much forgetfulness.

Table 4.

Improvement of dry eye symptoms according to the degree of conjunctival hyperemia in the subgroup of compliant patientsa

| Dry eye symptoms | Baseline (visit 0)

|

Visit at 12 weeks

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None/mild | Moderate/severe | None/mild | Moderate/severe | ||

| Scratchy | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.8) | |

| Stinging sensation | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.7) | |

| Grittiness | 1.3 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.7) | |

| Painful eyes | 0.4 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.6) | |

| Tired eyes | 0.7 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.7) | |

| Grating sensation | 0.9 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.7) | |

| Blurry vision | 0.5 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.6) | |

|

|

|||||

| Difference 12 weeks vs baseline | |||||

|

|

|||||

| None/mild | Moderate/severe | P-value | |||

|

|

|||||

| Scratchy | −0.6 (0.7) | −0.9 (0.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Stinging sensation | −0.7 (0.7) | −1.0 (0.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Grittiness | −0.7 (0.7) | −1.2 (0.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Painful eyes | −0.2 (0.5) | −0.7 (0.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Tired eyes | −0.4 (0.6) | −0.8 (0.9) | <0.001 | ||

| Grating sensation | −0.7 (0.7) | −1.0 (0.8) | <0.001 | ||

| Blurry vision | −0.3 (0.6) | −0.7 (0.8) | <0.001 | ||

Notes: Data as mean (standard deviation).

Compliant: always took the three capsules every day.

A total of 960 patients (76.5%) did not report any adverse events. In the remaining 23.5% of patients in whom adverse events occurred, the most frequent was fish-tasting regurgitation in 16.9% of patients, followed by nausea in 4.7% of patients, diarrhea in 1% of patients, and vomiting in 0.3% of patients. None of the patients were withdrawn from the study because of adverse events.

In relation to the level of patient satisfaction regarding clinical improvement of dry eye symptoms, 21.9% were very satisfied, 60% satisfied, and 18% not at all satisfied. Also, 31.3% of ophthalmologists rated clinical improvement as large, 56.4% of them rated it as mild, and 12.4% of them rated it as no improvement.

Discussion

The present study, which was carried out in a very large clinical series of patients with chronic glaucoma and ocular surface dysfunction due to the long-term instillation of anti-hypertensive eye drops, shows that dietary supplementation with essential fatty acids and antioxidants appears effective in relieving symptoms of dry eye syndrome. Other positive effects included decreased artificial tears usage (although this cannot be considered clinically significant), reduced conjunctival hyperemia, and improved tear film parameters. A 3-month treatment of the supplement prescribed as three capsules a day was associated with a clinical improvement of all characteristic symptoms of dry eye (scratchy and stinging sensation, redness, grittiness, blurry vision, etc.) with statistically significant differences for comparisons between the end of treatment and baseline. Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids cannot be synthesized in the body and must be obtained from the diet. In this respect, incorporation of omega-3 into the diet is encouraged by many dietitians and health care professionals.

Chronic topical therapeutic management of glaucoma has the potential to deleteriously alter the ocular surface, mostly due to the preservatives in eye drops (such as benzalkonium chloride) rather than the active IOP-lowering drug component.30 Chronic treatment with preserved topical drugs combined with age-related dry eye exposes patients with glaucoma to the risk of developing ocular surface disease with the evidence of dry eye syndrome. Dry eye syndrome is a recognized group of disorders that culminate in the production of common signs and symptoms affecting the ocular surface and the tear film. Ocular inflammation is the single most common accompanying finding.31 It has been shown that omega-3 supplementation has an anti-inflammatory effect,21,23 inhibiting the formation of omega-6 prostaglandin precursors. Omega-3 essential fatty acids also show anti-inflammatory action in the lacrimal gland, thus preventing apoptosis of secretory epithelial cells. Supplementation of essential fatty acids clears meibomitis, allowing a thinner, more elastic lipid layer to protect the tear film and cornea.25,32 On the other hand, the guidelines proposed by the International Dry Eye Workshop33 suggest that anti-inflammatory therapy needs to be instated in patients with moderate subjective discomfort, annoying visual symptoms, TBUTs <10 seconds, and Schirmer scores <10 mm (wetting in 5 minutes). Oral omega-3 fatty acid intake is a recommended anti-inflammatory treatment modality at this stage.

The present results suggest significant improvements of dry eye symptoms and other related parameters, resulting from the antioxidant–anti-inflammatory properties of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, and add evidence to the findings of previous studies.21–23,25,26 However, as far as we are aware, this is the first study in which the effectiveness and tolerability of this nutraceutical supplementation was examined in patients with glaucoma and dry eye symptoms. In a study of patients with glaucoma and dry eye disorders on long-term treatment with antihypertensive eye drops in which the oral supplement was Brudysec 1.5 g (very similar to that used in our patients), the main signs and symptoms of dry eye were significantly improved after 3 months of treatment as compared to patients not supplemented with the drug.21 Also, in a randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids in the dry eye syndrome, administration of one capsule containing 325 mg eicosapentaenoic acid and 175 mg docosahexaenoic acid for 3 months (264 eyes) was associated with statistically significant differences as compared to placebo trial (254 eyes) in symptom scores, Schirmer test, TBUT values, Rose Bengal score (as a measure of ocular surface integrity), and conjunctival impression cytology scores. These excellent results are in agreement with our study findings.34 Moreover, we found a significant decrease in IOP values, but this observation is difficult to be interpreted because of the normal diurnal variation of IOP measurements. Also, changes in antihypertensive eye drops during the study period were not evaluated.

Recently, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Bae et al35 reported that Korean red ginseng supplementation given for 8 weeks significantly improved tear film stability and total ocular surface disease index score in patients with glaucoma and established topical hypotensive therapy, confirming the previous findings of an earlier study performed by the authors.36 Ginseng (the root of Panax ginseng) contains a variety of active components, including ginsenoides, polysaccharides, peptides, polyacetylenic alcohols, and fatty acids.

Recent advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of dry eye syndrome have led to the evolution of newer modalities of treatment. Omega-3 fatty acids modulate the inflammatory process, and nutritional supplementation has a promising role in alleviating the dry eye syndrome. Dietary intervention with omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants not only causes symptomatic relief but also improves the clinical markers of dry eye, probably in the inherent stability of the tear film as observed by changes in TBUT and Schirmer test scores. Other lines of research include the role of the dopaminergic system and the usefulness of dopamine receptor (DA2 and DA3) agonists to influence the modulation of IOP.37 In an experimental study, in rats with induced ocular hypertension, dietary supplementation with a combination of alpha-lipoic acid and superoxide dismutase for 8 weeks versus no product showed lack of fluorescence in the retinal ganglion cells and astrocytes of the optic nerve, indicating that an increase in alpha-lipoic acid and superoxide dismutase exerts an antiapoptotic effect and protects against oxidative stress.38

Our study has some important limitations, including the fact that differences according to the type of glaucoma or topical antihypertensive medications were not assessed and the open-label nature of the design. Despite the well-known disadvantages of an open-label design (eg, introduction of bias through unblinding), open-label trials are less complex and can be conducted at lower costs, and thus can be used to recruit more patients and to improve the value of results of clinical studies. In the present study, the open-label design was very useful to recruit a large number of patients diagnosed of glaucoma with dry eye symptoms in order to replicate the favorable results obtained in previous studies21,22 using an oral omega-3 supplement in the patients with dry eye syndrome attended during routine daily practice. Some variables measured in the study may vary with the time of the day. However, the time of day when the measurements were conducted was not controlled or was the time of the last drop instillation. Moreover, it may be argued that 12 weeks of administration of the nutraceutical supplement is too small, but given the large dose administered (1 g of docosahexaenoic acid per day), improvement of dry eye symptoms could be obtained even before reaching the 3-month period.

In a previous study by our group in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction, significant increases in TBUT as compared with baseline were already observed after 1 month of supplementation with essential fatty acids.25 Finally, patients enrolled in the study can be considered broadly as representatives of the population of patients with glaucoma in Spain, who were diagnosed and managed by their ophthalmologists in the outpatient setting.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the administration of a nutraceutical supplement based on omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids combined with vitamins, antioxidants, and minerals during a 3-month period in patients with glaucoma using chronic instillation of antihypertensive eye drops may be an effective and well-tolerated treatment for the dry eye syndrome. Further studies with a longer treatment period and a better design, such as randomized controlled trials, are necessary to assess the long-term effects and confirm the effectiveness of this supplement. This nutritional supplement, however, may be a clinically valuable additional option for dry eyes in patients with glaucoma using antiglaucoma eye drops.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Brudy Laboratories, Barcelona, Spain. The participation of the sponsor was limited to distribution and collection of the case record forms from the participating ophthalmologists, but without any involvement in the tasks of creating the database, performing the statistical analysis, interpreting the results, or writing the article. The author thanks Sergi Mojal for statistical analysis, Marta Pulido, MD, for editing the article and editorial assistance, and Jaime Borras, MD, for monitoring the trial. Members of the Dry Eye In Glaucoma Study Group (DEIGSG) are as follows: Jesús Tellez-Vazquez, Isabel Romagosa Robles, José Pinós Rajadel, José Miguel Camacho, Manuel Camacho Sanpelayo, Jorge Saa Gómez, Mariano Royo Sans, Eloísa Mejías González, Mariona Darné Freixenet, Hassane Ismail Hamed, Montserrat Gaya Catasús, José Manuel Navero Rodríguez, Carmen del Pozo Rodríguez, C Kaan Uzun Ozkok, Emanuel Marco Bogado, Marta Nadal Vall, Patricio M Aduriz Lorenzo, Pedro Pérez Reyes, Edurne Etxeandía, Antonio Raez Vázquez, Eduardo Conesa, Sara Ortíz Ortigosa, Juan Junceda Moreno, José Mora Castilla, Sergio Pinar Sueiro, Amagoia Arteagabeitia, Javier Paz Moreno, Luciano Donzis, Juan Antonio Jiménez Velázquez, José Javier García Medina, José Zamora Barrios, Alfonso Quinteiro Alonso, Maria Soledad Leonato Domínguez, Jonatan Amián Cordero, Ana Piñero Bustamante, Osvaldo Guevara, Katia Llanos, María Iglesias Álvarez, Maria Dolores Mosqueira Zamora, Mónica Vásquez Barrero, Maria Asunción García Medina, Juan Fco. Ramos López, Sebastián Alarcón Díaz, Emilia Sánchez Blanque, Constanza García Torres, José M Gutiérrez Iglesias, Manuel Roldán, Carmen Junceda Moreno, Tomás Parra Rodríguez, Kattia Sotelo Monge, Vanesa Cuadrado Claramonte, Maria Montserrat Miró Roig, Robert Arranz Fernández, Isabel Esturi Navarro, Patricia Udaondo, Juan Marín Montiel, Aitor Lanzagorta, Ángel Luís López Ramos, Fernando Hernández Pardines, Maria José Grech Ríos, Maria Victoria Montoya Alfaro, Gema Pacheco, Ruymán Rodríguez Gil, Pedro Pablo Rodríguez Calvo, and Ignacio Montero Espinosa.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author and the DEIGSG members state that they have no conflicts of interest, or proprietary or financial interests in the products mentioned in this work.

References

- 1.Uchino M, Scahumberg DA. Dry eye syndrome: impact on quality of life and vision. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2013;1:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s40135-013-0009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asbell PA. Increasing importance of dry eye syndrome and the ideal artificial tear: consensus views from a roundtable discussion. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:2149–2157. doi: 10.1185/030079906X132640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolando M, Zierhut M. The ocular surface and tear film and their dysfunction in dry eye disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45(suppl 2):S203–S210. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson ME, Murphy PJ. Changes in the tear film and ocular surface from dry eye syndrome. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004;23:449–479. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson ME. The association between symptoms of discomfort and signs in dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2009;7:199–211. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols KK, Nichols JJ, Mitchell GL. The lack of association between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease. Cornea. 2004;23:762–770. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000133997.07144.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi CG, Pasinetti GM, Scudeller L, et al. Ocular surface disease and glaucoma: how to evaluate impact on quality of life. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013;29:390–394. doi: 10.1089/jop.2011.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossi GC, Tinelli C, Oasinetti GM, et al. Dry eye syndrome-related quality of life in glaucoma patients. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:572–579. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung EW, Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN. Prevalence of ocular surface disease in glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:350–355. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815c5f4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fechtner RD, Godfrey DG, Budenz D, et al. Prevalence of ocular complaints in patients with glaucoma using topical intraocular pressure-lowering medications. Cornea. 2010;29:618–621. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181c325b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erb C, Gast U, Schremmer D. German register for glaucoma patients with dry eye.I. Basic outcome with respects to dry eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Opthalmol. 2008;246:1593–1601. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0881-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa VP, Marcon IM. Galvão Filho RPm Malta RFS. The prevalence of ocular complaints in Brazilian patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2013;76:221–225. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492013000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baudouin C, Liang H, Hamard P, et al. The ocular surface in glaucoma patients treated over the long term expresses inflammatory markers related to both T-helper and T-helper 2 pathways. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broadway D, Grierson I, Hitchings R. Adverse effects of topical antiglaucomatous medications on the conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:590–596. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.9.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali F, Akpek EK. Glaucoma and dry eye. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1232. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong L, Petznick A, Lee S, et al. Choice of artificial tear formulation for patients with dry eye: where do we start? Cornea. 2012;31(suppl 1):S32–S36. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318269cb99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guzey M, Satici A, Karaman SK, et al. The effect of lubricating eye drop containing hydroxypropyl guar on perimetry results of patients with glaucoma and trachomatous dry eye. Opjthalmologica. 2010;224:109–115. doi: 10.1159/000235924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yenice O, Temel A, Orüm O. The effect of artificial tear administration on visual field testing in patients with glaucoma and dry eye. Eye (London) 2007;21:214–217. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dana MR, Hamrah P. Role of immunity and inflammation in corneal and ocular surface disease associated with dry eye. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;506:729–738. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0717-8_103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macri A, Scanarotti C, Bassi AM, et al. Evaluation of oxidative stress levels in the conjunctival epithelium of patients with or without dry eye, and dry eye patients treated with preservative-free hyaluronic acid 0.15% and vitamin B12 eye drops. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;253(3):425–430. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2853-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galbis-Estrada C, Pinazo-Durán MD, Cantú-Dibildox J, et al. Patients undergoing long-term treatment with antihypertensive eye drops respond positively with respect to their ocular surface disorder to oral supplementation with antioxidants and essential fatty acids. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:711–719. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S43191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oleñik A, Dry Eye Clinical Study Group (DECSG) Effectiveness and tolerability of dietary supplementation with a combination of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and antioxidants in the treatment of dry eye symptoms: results of a prospective study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:169–176. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S54658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinazo-Durán MD, Galbis-Estrada C, Pons-Vázquez S, et al. Effects of a nutraceutical formulation based on the combination of antioxidants and ω-3 essential fatty acids in the expression of inflammation and immune response mediators in tears from patients with dry eye disorders. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:139–148. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S40640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kangari H, Eftekhari MH, Sardari S, et al. Short-term consumption of oral omega-3 and dry eye syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2191–2196. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oleñik A, Jiménez-Alfaro I, Alejandre-Alba N, et al. A randomised, double-masked study to evaluate the effect of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1133–1138. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S48955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oleñik A, Mahillo-Fernández I, Alejandre-Alba N, et al. Benefits of omega-3 fatty acid dietary supplementation on health-related quality of life in patients with meobian gland dysfunction. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:831–836. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S62470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong NH, Purcell TL, Roch-Levecq AC, et al. Epithelial healing and visual outcomes of patients using omega-3 oral nutritional supplements before and after photorefractive keratectomy: a pilot study. Cornea. 2013;32:761–765. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31826905b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brudy Technology SL European patent EP 196 825 B1. DHA for treating pathology associated with cellular oxidative damage. EP 196 825 B1. European patent. 2004 Apr 02;

- 29.Bron A, Evans VE, Smith JA. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003;22:640–650. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossi GC, Pasinetti GM, Scudeller L, et al. Risk factors to develop ocular surface disease in treated glaucoma or ocular hypertension patients. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013;23:296–302. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tavares Fde P, Fernandes RS, Bernardes TF, et al. Dry eye disease. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25:84–93. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2010.488568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roncone M, Bartlett H, Eperjesi F. Essential fatty acids for dry eye: a review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Management and therapy of dry eye disease: report of the Management and Therapy Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) Ocul Surf. 2007;5:163–178. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhargava R, Kumar P, Kumar M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids in dry eye syndrome. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6:811–816. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.06.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bae HW, Kim JH, Kim S, et al. Effect of Korean Red Ginseng supplementation on dry eye syndrome in glaucoma patients – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim NR, Kim JH, Kim CY. Effect of Korean red ginseng supplementation on ocular blood flow in patients with glaucoma. J Ginseng Res. 2010;34:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pescosolido N, Parisi F, Russo P, et al. Role of dopaminergic receptors in glaucomatous disease modulation. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:193048. doi: 10.1155/2013/193048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nebbioso M, Scarsella G, Tafani M, et al. Mechanisms of ocular neuroprotection by antioxidant molecules in animal models. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2013;27:197–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]