Abstract

Objective

To examine the rate and variation in RA-related hand and wrist surgery among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States and identify the patient and provider factors that influence surgical rates.

Methods

Using 2006–2010 100% Medicare claims data of beneficiaries with RA diagnosis, we examined rates of rheumatoid hand and wrist arthroplasty, arthrodesis and hand tendon reconstruction in U.S. We used multivariate logistic regression models to examine variation in receipt of surgery by patient characteristics, provider factors (regional density of rheumatologists, orthopaedic surgeons and plastic surgeons) and rate of biologics use.

Results

Between 2006 and 2010, the annual rate of RA-related hand and wrist arthroplasty or arthrodesis was 23.1 per 10,000 patients, and the annual rate of hand tendon reconstruction was 4.2 per 10,000 patients. The rates of surgery varied 9-fold across hospital referral regions in U.S. Younger patient age, female gender, white race, higher socioeconomic status (SES) and rural residence were associated with higher likelihood of undergoing arthroplasty and arthrodesis. We observed no significant difference in rate of arthroplasty and arthrodesis by density of orthopaedic and plastic surgeons or biologics use, but a significant decrease in the rate with increasing density of rheumatologists. However, the receipt of hand tendon reconstruction was not influenced by provider factors, but only correlated with age, race, SES and rural status of the patients.

Conclusions

Surgical reconstruction of rheumatoid hand deformities varies widely across the United States, driven by both regional availability of subspecialty care in rheumatology and individual patient factors.

Key indexing terms: rheumatoid arthritis, hand, wrist, surgery, Medicare

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, debilitating, immune-mediated disease involving progressive joint destruction, commonly affecting the small joints of the hand and wrist. Unfortunately, the incidence and prevalence of RA are rising among older individuals.[1, 2] Although there is no cure, surgical intervention, such as joint arthroplasty and arthroplasty, can improve pain and deformity for patients with RA, and many patients report improved satisfaction and independence in daily life. [3–6]

Nonetheless, the role of surgery for RA remains controversial. Many clinicians view surgery as a failure of medical management, and prospective cohort studies in several countries suggest a declining rate of RA-related joint procedures, [7–11] likely due to advances in medical therapy. [12, 13] In the United States, rheumatologists and surgeons debate the effectiveness, timing, and indications for surgery, and prior studies have demonstrated large area variation in the rate of hand surgery among patients with RA.[14, 15] Given this uncertainty, rates of surgery could represent systematic differences in access to appropriate, high quality subspecialty care.

Currently, the factors that are correlated with undergoing RA-related hand and wrist are unknown, but could reveal differences in access to care, physician practice patterns, and treatment effectiveness. In this context, we examined the rates of surgical procedures performed for rheumatoid hand and wrist deformities among all Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with RA from 2006 to 2010 in order to 1) define the national variation in RA-related hand and wrist surgery and 2) identify the patient and regional factors that influenced this variation. We hypothesized measurable variation exists in the rates of surgery among elderly patients with rheumatoid hand and wrist deformities, due to both patient and regional factors.

Methods

Study sample and data source

Our study sample was drawn from 100% Medicare beneficiaries who were diagnosed with RA and enrolled in fee-for-service (FFS) programs between 2006 and 2010. To increase the reliability of the diagnosis of RA, our study cohort included beneficiaries with at least 2 diagnoses of RA (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision/ICD-9 codes for RA: 714.0, 714.1, 714.2, 714.3, 714.4) listed ≥7 or more days apart between 2006 and 2010.[16] Additionally, we included beneficiaries ages >65 years who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A and B during each calendar year. We excluded all beneficiaries who were enrolled in Medicare Advantage Plans (Part C) due to the lack of outpatient claims data in Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) databases. Using residence ZIP code, we further limited our analysis to beneficiaries who resided within the 50 states and Distinct of Columbia during the study period. Each study subject entered the cohort in the year of diagnosis of RA, and remained in the cohort until the year of death, disenrollment, or end of the study.

We specifically reviewed all outpatient services for the RA cohort during the study period drawn from the Outpatient files and the Carrier files. We obtained demographic data and confirmed enrollment status using the Annual Beneficiary Summary Files. The Outpatient file contains all fee-for-service claims submitted by outpatient providers, and the Carrier file contains claims submitted by non-institutional providers such as physicians, physician assistants and nurse practitioners. Both files use ICD-9 codes to detail diagnosis, and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes to detail procedures.

Dependent Variables

Our outcome variables included RA-related hand and wrist surgical procedures, identified by CPT codes. (Table 1) Arthrodesis procedures included carporadial, carpometacarpal (CMC), metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and interphalangeal (IP) joint arthrodesis. Arthroplasty procedures included reconstruction with or without implants of the MCP, IP, CMC, intercarpal, and wrist joints. We also included tendon reconstructive procedures, specifically tenolysis, extensor tendon repair, and tendon transfers.

Table 1.

Rheumatoid arthritis-related procedures of the hand and wrist

| Procedure | Anatomic Location | CPT Codes | Number of patients |

Annual rate¥ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthroplasty | Wrist | 25332,25441 | 63 | 0.5 |

| Intercarpal or carpometacarpal joints |

25447 | 307 | 2.6 | |

| Metacarpophalangeal joint | 26530, 26531 | 1,322 | 11.3 | |

| Interphalangeal joint | 26535, 26536 | 390 | 3.3 | |

| Arthrodesis | Wrist | 25800,25805,25810,2 5820,25830 |

420 | 3.6 |

| Carpometacarpal joint | 26841, 26843,26844 | 58 | 0.5 | |

| Metacarpophalangeal joint | 26850,26852,26853 | 428 | 3.7 | |

| Interphalangeal joint | 26860,26861,26862,2 6823 |

737 | 6.3 | |

| Tenolysis | Extensor tendon, hand, finger, forearm |

26445, 26449 | 86 | 0.7 |

| Proximal PIP joint | 26460 | 75 | 0.7 | |

| Digital joint | 26471, 26474 | 45 | 0.4 | |

|

Tendon repair |

Extensor tendon, hand and finger |

26410, 26412, 26418, 2 6420 |

175 | 1.5 |

| Extensor tendon, central slip | 26426, 26428 | 54 | 0.5 | |

| Tendon Transfer | Ring and small fingers | 26497 | 72 | 0.6 |

| All four fingers | 26498 | 50 | 0.4 |

: Annual rate was calculated as number of RA patients who received the procedure per 10,000 patients per year.

Independent variables

Patient Factors

We examined the characteristics of each study subject at the time of their entry into the study cohort. We specifically included age (categorized as 65–69 years, 70 to 74 years, 75 to 80 years, and ≥80 years), race (white, African American, and other), sex and socioeconomic status (SES). SES was estimated using ZIP code of beneficiary residence and then categorized into three categories (high, medium, and low).[17] As an additional measure of SES, we examined whether each beneficiary received state assistance in Medicare premium using the ‘Medicare State Buy-In’ variable in Beneficiary Summary File. We identified these recipients if the beneficiary received the assistance for more than 6 months in the year entering the cohort. Additionally, we controlled for the overall health condition of study subjects in our analysis using Elixhauser’s comorbidity index.[18] Finally, we determined rural and urban residence for each subject using 1993 US Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban Continuum Codes for Metro and Non-metro Counties.[19] Counties are labeled by their Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) codes and categorized into metropolitan counties (codes 1–3), non-metropolitan counties with more than 2,500 urban population (codes 4–7) and completely rural counties (codes 8–9) in this database. We used the SAS 9.2 ZIP code help file, containing crosslink of ZIP code and FIPS code for each county in the U.S. to link the FIPS code in Rural-Urban Continuum Codes file to the residence ZIP code of our study cohort to assign rural status for each patient.

Regional Factors

Hospital referral regions (HRRs) are defined by the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care and represent regional health care markets for tertiary medical care, including 306 distinct regions in the U.S. according to patterns of hospital use.[20] We assigned each subject in the study cohort to an HRR by ZIP code of permanent residence regardless of where the procedure was performed for the patient.

To understand the effect of regional availability of specialist care, we obtained density of rheumatologists, orthopaedic surgeons and plastic surgeons within each HRR. This is detailed in the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care as the number of specialists per one million residents per region. We then categorized provider density into evenly distributed tertiles.

To understand the effect of regional patterns of medical therapy, we calculated the rate of utilization of biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) by each HRR. To do this, we identified use of biologic DMARDs from Medicare outpatient claims and Medicare Part D Prescription Drug events by Healthcare Common Procedure codes and generic name of drugs. (Appendix 1) We calculated annual rate of biologic DMARDs use for each HRR as average percent of RA patients who received biologic DMARDs from 2006 to 2010.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to detail the overall rates of RA-related hand and wrist surgery, and the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population. We then constructed multivariate logistic regression models to understand the effect of patient and regional factors on RA-related hand and wrist surgery. To examine the influence of regional availability of specialists on RA-related surgery, we also included density of orthopaedic surgeons, plastic surgeons and rheumatologists of the region where each study subject resided into the model as predictors of receiving RA surgery. Finally, we adjusted each model for number of years in the study cohort and regional density of biologics therapy in our model.

Results

In our cohort of Medicare beneficiaries, we identified 356,061 individuals diagnosed with RA, and 2,895 of these patients underwent RA-related hand and wrist reconstructive surgery during the period (annual rate= 24.8/10,000 patients). Among patients who underwent surgery, 2,693 patients underwent hand or wrist arthroplasty or arthrodesis (annual rate=23.1/10,000 patients) and 488 underwent received tendon reconstruction (annual rate= 4.2/10,000 patients). MCP joint arthroplasty was the most commonly performed surgery (annual rate=11.3/10,000 patients), followed by interphalangeal joint arthrodesis (annual rate= 6.3/10,000 patients). Among tendon reconstruction procedures, extensor tendon repair was most commonly performed (annual rate=1.5/ 10,000 patients). (Table 1)

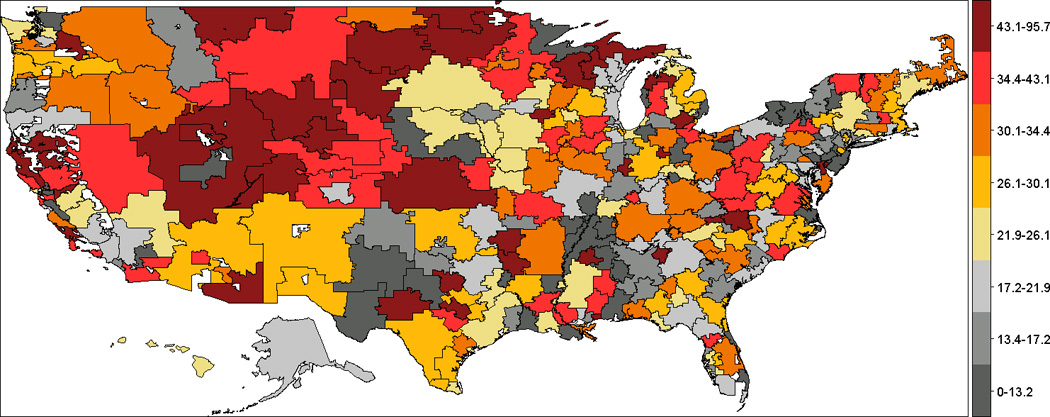

Figure 1 demonstrates the crude rates of RA-related hand and wrist surgery across the United States. Across HRRs, annual rates of surgery varied 9-fold, ranging from no surgeries performed in four small regions in east or south of US: Lancaster (PA), Longview (TX), Houma (LA) and Muskegon (MI) to more than 80 per 10,000 patients in Ogden (UT), Grand Forks (ND) and Fort Collins (CO). Clusters of high annual rates of RA-related hand and wrist surgery appeared in West Coast and Central areas of the U.S., and clusters of low surgical rates appeared in eastern states, such as New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

Figure 1.

Patient factors significantly influenced receipt of hand and wrist surgery for RA, specifically age, gender, race, and SES. (Table 3) For example, RA patients ages ≥80 years were less likely to undergo hand or wrist arthroplasty and/or arthrodesis compared to patients ages 65 to 69 years (OR= 0.29; 95% CI: 0.25–0.34). Females were more likely to undergo arthroplasty and/or arthrodesis compared with males (OR = 2.05; 95% CI: 1.85–2.28), and African-American patients were less likely to undergo joint procedures compared with whites (OR=0.58; 95% CI: 0.48–0.70). Compared to patients who lived in metropolitan counties, patient who lived in rural areas were more likely to undergo arthroplasty and/or arthrodesis (OR=1.31; 95% CI: 1.04–1.66). Finally, patients of higher SES were more likely to undergo arthroplasty and/or arthrodesis compared with patients of lower SES (OR=1.20; 95% CI: 1.08–1.34).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics of the study cohort and adjusted odds ratios of receiving RA-related hand or wrist surgery during the study period.

| Arthroplasty/Arthrodesis | Tendon reconstructive procedures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | OR (95% CI)¥ | P values | OR (95% CI)¥ | P values |

| Age | ||||

| 65–69 | 1 | - | 1 | |

| 70–74 | 0.93 (0.85–1.02) | 0.12 | 1.13 (0.91–1.40) | 0.26 |

| 75–79 | 0.68 (0.61–0.76) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.64–1.06) | 0.13 |

| >=80 | 0.29 (0.25–0.34) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.28–0.53) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Female | 2.05 (1.85–2.28) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.30–2.07) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1 | - | 1 | |

| African-American | 0.58 (0.48–0.70) | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.42–1.00) | 0.05 |

| Other | 0.79 (0.63–0.98) | 0.03 | 0.80 (0.47–1.35) | 0.40 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||

| Low | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Medium | 1.15 (1.03–1.29) | 0.01 | 1.35 (1.02–1.77) | 0.03 |

| High | 1.20 (1.08–1.34) | 0.001 | 1.41 (1.08–1.85) | 0.01 |

| State Financial Assistance in Medicare Premium | ||||

| No | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.01 (0.88–1.15) | 0.93 | 0.79 (0.55–1.13) | 0.19 |

| Rural Status | ||||

| Metropolitan county | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Non-Metropolitan county | 1.13 (1.02–1.26) | 0.02 | 0.96 (0.73–1.25) | 0.76 |

| Completely rural | 1.31 (1.04–1.66) | 0.02 | 1.92 (1.19–3.09) | 0.007 |

| Density of orthopedic surgeons | ||||

| Low (Less than 58) | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Medium (58 to 67) | 1.00 (0.91–1.11) | 0.99 | 0.87 (0.69–1.10) | 0.26 |

| High (More than 67) | 1.16 (1.05–1.29) | 0.004 | 0.91 (0.71–1.15) | 0.43 |

| Density of plastic surgeons | ||||

| Low (less than 15) | 1 | - | ||

| Medium (15 to 21) | 1.10 (1.01–1.21) | 0.04 | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) | 0.61 |

| High (More than 21) | 0.95 (0.85–1.05) | 0.32 | 1.05 (0.82–1.33) | 0.71 |

| Density of rheumatologists | ||||

| Low (Less than 9) | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Medium (9 to 13) | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) | 0.54 | 1.10 (0.88–1.38) | 0.41 |

| High (More than 13) | 0.76 (0.69–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.75–1.24) | 0.80 |

| Regional rate of biologics use | ||||

| Low (1.0% to 4.3%) | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Medium (4.3% to 5.6%) | 0.97 (0.89–1.07) | 0.60 | 1.11 (0.88–1.38) | 0.38 |

| High (5.6% to 13.6%) | 0.96 (0.88–1.06) | 0.46 | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) | 0.90 |

: Adjusted odds ratios of receiving hand and wrist arthroplasty/arthrodesis or tendon reconstruction during the study period, adjusting simultaneously by age, sex, race, number of comorbid conditions, socioeconomic status, state financial assistance, rural status, and density of specialists, regional rate of biologics use, as well as number of years each individual stayed in the study cohort.

Tendon reconstruction was also influenced by patient factors. Similar to joint reconstructive procedures, younger (OR=2.63, 95%CI: 0.28–0.53), female (OR=1.64, 95%CI: 1.89–3.57) patients were more likely to undergo tendon reconstruction compared with older, male patients. Additionally, African-American patients (OR=0.65, 95%CI: 0.42–1.00) and patients of lower SES (OR=0.71, 95%CI: 054–0.96) were less likely to undergo tendon reconstruction. Finally, patients who lived in rural areas were more likely to undergo reconstruction (OR=1.92, 95%CI: 1.19–3.09), compared with patients who lived in urban areas. (Table 3)

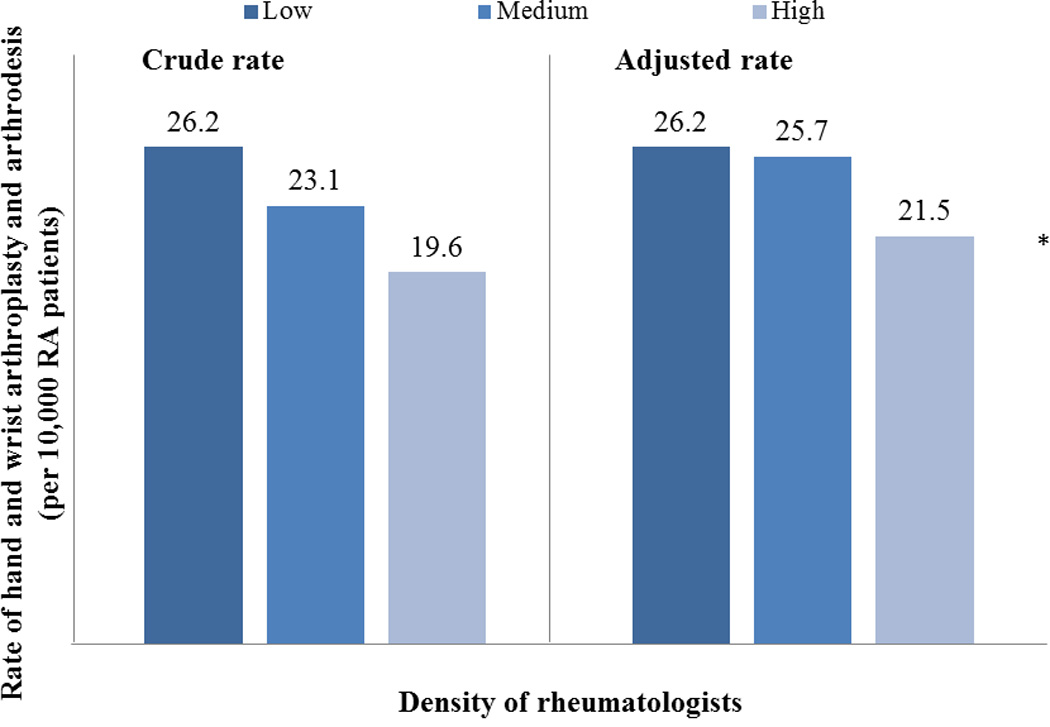

We examined the effect of regional density of specialists on RA-related hand and wrist surgery. In our cohort, patients who resided in areas with a high density of orthopedic surgeons were more likely to undergo arthroplasty and/or arthrodesis (OR=1.16; 95%CI: 1.05–1.29) compared with patients who lived in areas with a lower density of orthopedic surgeons. The effect of plastic surgeon density was less uniform, and patients who lived in areas with a moderate density of plastic surgeons were more likely to undergo arthroplasty and/or arthrodesis compared with patients who lived in areas with a lower density of plastic surgeons (OR=1.10; 95%CI: 1.01 – 1.21). However, the same effect was not seen among patients living in areas with the highest density of plastic surgeons. Surgeon density did not influence tendon reconstruction procedures. Alternatively, regional density of rheumatologists was significantly associated with likelihood of receiving hand and wrist arthroplasty and arthrodesis among RA patients. Patients who lived in areas with more than 13 rheumatologists/1 million residents were significantly less likely to undergo surgery (OR=0.76; 95% CI: 0.69–0.85) compared to patients who lived in areas with less than 10 rheumatologists/ million residents. (Table 3) We then examined the crude and adjusted rates of arthroplasty and arthrodesis, stratified by rheumatologist density (Figure 2). Even after adjusting for other patient and regional factors, rates of surgery remained lower among areas with a higher density of rheumatologists. After controlling for all patient and provider characteristics, regional density of biologics use was not significantly correlated with rate of RA-related hand and wrist surgery.

Figure 2.

*: P <0.05, from multivariate logistic regression model, adjusting simultaneously by all patient and provider characteristics, and number of years in study cohort.

Finally, we examined the differences in patient characteristics among individuals who resided in areas of low, medium and high rheumatologist density. (Table 4) In our cohort, age, gender, race, SES, and rural status were significantly associated with the area each patient lived. For example, areas with high density of rheumatologists, 25% of RA patients were ages ≥80 years and 29% were 65 to 69, compared with lower density areas, in which 19% of patients were ≥80 years and 34% were ages 65 to 69 (p<0.001). Areas with high density of rheumatologists also had significantly more metropolitan patients (89% vs. 74%, p <0.001). Finally, higher density areas were also associated with greater percent of high SES patients (66% in high density areas vs. 40% in low density areas, p <0.001).

Table 4.

Distribution of baseline patient characteristics by density of rheumatologists of the hospital referral region.

| Density of rheumatologists | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Low | Medium | High | P value |

| Age* | ||||

| 65–69 | 34% | 32% | 29% | <0.001 |

| 70–74 | 26% | 25% | 24% | |

| 75–79 | 21% | 21% | 22% | |

| >=80 | 19% | 22% | 25% | |

| Sex* | ||||

| Male | 27% | 26% | 25% | <0.001 |

| Female | 73% | 74% | 75% | |

| Race* | ||||

| White | 90% | 87% | 88% | <0.001 |

| African-American | 6% | 7% | 8% | |

| Other | 3% | 5% | 4% | |

| Socioeconomic Status* | ||||

| Low | 25% | 20% | 11% | <0.001 |

| Medium | 31% | 29% | 21% | |

| High | 40% | 48% | 66% | |

| Missing | 4% | 4% | 2% | |

| Rural Status* | ||||

| Metropolitan county | 74% | 80% | 89% | <0.001 |

| Non-Metropolitan county | 22% | 18% | 9% | |

| Completely rural | 3% | 2% | 1% | |

Discussion

RA remains common among older individuals, afflicting over 350,000 Medicare beneficiaries from 2006 to 2010. In this study, we identified a low rate of RA-related hand and wrist reconstructive procedures among elderly population in the U.S., but found substantial variation in RA-related hand and wrist procedures, driven by regional and patient factors. Patients who lived in areas with a greater number of rheumatologists were less likely to undergo RA-related hand and wrist joint fusion and replacement. Additionally, younger, female, white RA patients, and patients who resided in rural areas were more likely to undergo both arthroplasty/arthrodesis of hand and wrist and hand tendon reconstruction. Finally, in our cohort, patients of lower SES underwent fewer surgical procedures, including both joint and tendon reconstruction. Although the reasons for this are likely multifactorial, it is possible that individuals of lower SES lack access to appropriate specialist care, have additional comorbid conditions precluding aggressive medical or surgical intervention, or fewer available financial resources preventing them from seeking care.

Although almost 20 years have passed since Alderman et al. described regional differences in rheumatoid hand and wrist reconstruction using national claims data, pronounced variation in RA treatment persists. [15] Our findings suggest underscore the influence of providers on these differences. First, surgical rates may represent differential access to subspecialty care, particularly to rheumatologists with expertise in inflammatory arthropathies. In the U.S., a relative shortage of rheumatologists exists, and many RA patients are managed by non-subspecialty trained providers, who may opt for less aggressive immunosuppressive regimens, particularly among older individuals. [21] Individuals without access to newer disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may progress more quickly toward advanced deformities, resulting in higher rates of surgical therapy among those patients treated in areas with fewer rheumatologists. Additionally, our findings may represent differences in referral patterns for surgical intervention. Rheumatologists are often skeptical of the effectiveness of surgical interventions for RA, which influences referral rates for extremity surgery. Lower rates of surgery in some areas may reflect not only differences in aggressiveness of medical therapy, but also differences in treatment preferences. [14, 22, 23]

The majority of patients are referred to rheumatologists by primary care physicians following the diagnosis of RA, and surgeons are rarely the initial treatment provider. In the United States, approximately 70% of hand surgeons are trained in orthopedic surgery, 20% in plastic surgery, and 10% in general surgery [24] In our study, we identified a significant difference in rates of surgery by density of orthopedic surgeons. Surgeons often perceive that medical therapy is extended into advanced stages of RA, making it impossible to reconstruct functionally and aesthetically acceptable hands. [14, 15] To date, one of the largest prospective cohort studies of patients with rheumatoid hand deformities reveals that RA patients treated with silicone metacarpophalangeal arthroplasty continue to experience long-term improvement in hand function and appearance compared with patients managed medically. Therefore, despite this controversy, surgery remains an important option to relieve pain and improve function, hand appearance, and quality of life among RA patients. [3, 25, 26]

Finally, our findings may reflect the underlying geographic variation of the incidence of RA. Such geographic variation can be partly explained by different availability of rheumatologists in graphic areas. For example, the areas with high density of rheumatologists cluster in east coast of U.S., and these areas had lowest rate of RA-related hand and wrist surgery. An analysis of the Nurses Health Study revealed an increased incidence of RA among women in New England and the Midwest. [27] Although the etiology of RA remains unknown, there is likely regional variation in risk factors such as genetic pools or environmental factors that have yet to be identified. Therefore, unexplained regional variation in the medical and surgical treatment of RA may contribute to our findings.[28]

This study has several notable limitations. First, administrative data are subject to systematic coding errors, and is not collected with the explicit purpose of examining practice patterns. However, we required at least 2 claims including an RA diagnosis in order to ensure the validity of our selected cohort, and a recent study comparing diagnoses between office records and Medicare claims found a 90% correlation between diagnoses.[29] Due to the stringency of our criteria, it is possible that RA patients with limited access to care could be excluded from the cohort. Additionally, we excluded Medicare Part C enrollees (16–24% of all Medicare beneficiaries), as their outpatient services may not be captured in administrative claims data. Our study sample includes only adults ages ≥ 65 years, and our findings may not be generalizable to younger individuals with RA.[30] Finally, we are not able to examine the effect of disease severity or chronicity on surgical rates, given the lack of granular detail of claims data at this level. Without clinical data, such as laboratory findings, symptomsatology and radiographic progression, we cannot account for the influence of disease severity on rates of surgery. Nonetheless, Medicare data have been widely used to examine treatment patterns, and provide robust data due to large, population-based samples. Compared with clinical trials or observational registries that are biased toward tertiary care centers, CMS claims data reflect real-world clinical practice.[29, 31–33]

Despite these limitations, our findings reveal significant variation in RA treatment pattern by availability of rheumatologists, and highlight important areas of future investigation. First, access to appropriate healthcare resources has been central to healthcare reform initiatives in the United States. Several interventions, such as the expansion of prescription drug coverage through Medicare Part D and the expansion of Medicaid coverage from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, may minimize disparities in access to care for chronic diseases. For example, the initiation of Medicare Part D coverage of biologic DMARD therapy for RA has improved utilization among vulnerable groups.[34, 35] Additionally, healthcare reform initiatives have included specific provisions for comparative effectiveness research. Given the controversy that remains regarding the effectiveness of medical and surgical therapy for rheumatoid hand deformities, future studies that directly compare the effectiveness of surgical therapy in the setting of advanced medical therapies, such as biologic DMARDs, may allow for better integration of treatment options between rheumatologists and surgeons.

Surgical reconstruction of rheumatoid hand deformities varies across the United States due to the availability of rheumatologists and patient characteristics. Future efforts that directly examine the access to health care services, surgery referral pattern and effectiveness of medical and surgical treatment options as well as health policy interventions aimed at improving access to care can minimize unwarranted variation in the management of rheumatoid hand and wrist deformities.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study cohort

| Characteristics | Number of patients | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 65–69 | 112252 | 32% |

| 70–74 | 89542 | 25% |

| 75–79 | 76155 | 21% |

| >=80 | 78112 | 22% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 92595 | 26% |

| Female | 263466 | 74% |

| Race | ||

| White | 315407 | 89% |

| African American | 26290 | 7% |

| Other | 14364 | 4% |

| SES | ||

| Low | 79725 | 22% |

| Medium | 96135 | 27% |

| High | 180201 | 51% |

|

State assistance on Medicare premium |

||

| No | 319861 | 90% |

| Yes | 36200 | 10% |

| Rural status | ||

| Metropolitan county | 287893 | 81% |

| Non-Metropolitan county | 60340 | 17% |

| Completely rural | 7828 | 2% |

|

Density of orthopedic surgeons† |

||

| Low (Less than 58) | 115373 | 32% |

| Medium (58 to 67) | 120331 | 34% |

| High (More than 67) | 120357 | 34% |

| Density of plastic surgeons† | ||

| Low (less than 15) | 117763 | 33% |

| Medium (15 to 21) | 118437 | 33% |

| High (More than 21) | 119861 | 34% |

| Density of rheumatologists† | ||

| Low (Less than 9) | 117602 | 33% |

| Medium (9 to 13) | 117159 | 33% |

| High (More than 13) | 121300 | 34% |

| Regional rate of biologics use‡ | ||

| Low (1.0% to 4.3%) | 115850 | 33% |

| Medium (4.3% to 5.6%) | 120507 | 34% |

| High (5.6% to 13.6%) | 119704 | 34% |

: Density of specialists is number of specialists in each hospital referral region per 1,000,000 residents in the region.

: Average rate of biologics between 2006 and 2010 was calculated for each hospital referral region in US as percent of RA patients who received biologics therapy during the study period.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest:

This research is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR047328) and a 2013 Clinical Research Grant funded by the American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand (to Dr. Waljee).

References

- 1.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesotam, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1576–1582. doi: 10.1002/art.27425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung KC, Burke FD, Wilgis EF, Regan M, Kim HM, Fox DA. A prospective study comparing outcomes after reconstruction in rheumatoid arthritis patients with severe ulnar drift deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1769–1777. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a65b5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung KC, Kotsis SV, Kim HM. A prospective outcomes study of Swanson metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty for the rheumatoid hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavaliere CM, Chung KC. A systematic review of total wrist arthroplasty compared with total wrist arthrodesis for rheumatoid arthritis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:813–825. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318180ece3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waljee JF, Chung KC. Objective functional outcomes and patient satisfaction after silicone metacarpophalangeal arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss R, Ehlin A, Montgomery SM, Wick M, Stark A, Wretenberg P. Decrease of RA-related orthopaedic surgery of the upper limbs between 1998 and 2004: data from 54 579 Swedish RA inpatients. Rheumatol. 2008;47:491–494. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Engasaeter LB, Furnes O. Reduction in orthopedic surgery among patients with chronic inflammatroy joint disease in Norway, 1994–2004. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;57:529–532. doi: 10.1002/art.22628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Momohara S, Ikari K, T M. Declining use of synovectomy surgery for patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Japan. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009:291–292. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.087940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen AB, Johnsen SP, Overgaard S, Soballe K, Sorensen HT, Lucht U. Total hip arthroplasty in Denmark: incidence of primary operations and revisions during 1996–2002 and estimated future demands. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:182–189. doi: 10.1080/00016470510030553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikiphorou E, Carpenter L, Morris S, MacGregor AJ, Dixey J, Kiely P, et al. Hand and Foot Surgery Rates in Rheumatoid Arthritis Have Declined From 1986 to 2011, but Large-Joint Replacement Rates Remain Unchanged: Results From Two UK Inception Cohorts. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:1081–1089. doi: 10.1002/art.38344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korpela M, Laasonen L, Hannonen P, Kautiainen H, Leirisalo-Repo M, Hakala M, et al. Retardation of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis by initial aggressive treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: five-year experience from the FIN-RACo study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2072–2081. doi: 10.1002/art.20351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doan QV, Chiou C-F, Dubois RW. Review of eight pharmacoeconomic studies of the value of biologic DMARDs (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of managed care pharmacy: JMCP. 2006;12:555–569. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.7.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alderman AK, Ubel PA, Kim HM, Fox DA, Chung KC. Surgical management of the rheumatoid hand: consensus and controversy among rheumatologists and hand surgeons. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1464–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alderman AK, Chung KC, Demonner S, Spilson SV, Hayward RA. The rheumatoid hand: a predictable disease with unpredictable surgical practice patterns. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:537–542. doi: 10.1002/art.10662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Xie F, Delzell E, Chen L, Kilgore ML, Yun H, et al. Trends in the Use of Biologic Therapies among Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Enrolled in the US Medicare Program. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:1743–1751. doi: 10.1002/acr.22055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto FJ, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:99–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler MA, Beale CL. Rural-urban continuum codes for metro and nonmetro counties, 1993. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wennberg JE, Cooper M. The Dartmouth atlas of health care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deal CL, Hooker R, Harrington T, Birnbaum N, Hogan P, Bouchery E, et al. The United States rheumatology workforce: supply and demand, 2005–2025. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:722–729. doi: 10.1002/art.22437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glickel SZ. Commentary: Effectiveness of Rheumatoid Hand Surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burke FD, Miranda SM, Owen VM, Bradley MJ, Sinha S. Rheumatoid hand surgery: differing perceptions amongst surgeons, rheumatologists and therapists in the UK. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2011;36:632–641. doi: 10.1177/1753193411409830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunworth LS, Chintalapani SR, Gray RR, Cardoso R, Owens PW. Resident selection of Hand Surgery Fellowships: a survey of the 2011, 2012, and 2013 Hand Fellowship graduates. Hand. 2013;8:164–171. doi: 10.1007/s11552-013-9504-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung KC, Burns PB, Kim HM, Burke FD, Wilgis EF, Fox DA. Long-term followup for rheumatoid arthritis patients in a multicenter outcomes study of silicone metacarpophalangeal joint arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1292–1300. doi: 10.1002/acr.21705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alderman AK, Chung KC, Kim HM, Fox DA, Ubel PA. Effectiveness of rheumatoid hand surgery: contrasting perceptions of hand surgeons and rheumatologists. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28:3–11. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2003.50034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costenbader KH, Chang SC, Laden F, Puett R, Karlson EW. Geographic variation in rheumatoid arthritis incidence among women in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1664–1670. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards CJ, Campbell J, van Staa T, Arden NK. Regional and temporal variation in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis across the UK: a descriptive register-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz JN, Barrett J, Liang MH, Bacon AM, Kaplan H, Kieval RI, et al. Sensitivity and positive predictive value of Medicare Part B physician claims for rheumatologic diagnoses and procedures. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1594–1600. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tutuncu Z, Reed G, Kremer J, Kavanaugh A. Do patients with older-onset rheumatoid arthritis receive less aggressive treatment? Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1226–1229. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.051144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lauderdale DS, Furner SE, Miles TP, Goldberg J. Epidemiologic uses of Medicare data. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:319–327. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wailoo AJ, Bansback N, Brennan A, Michaud K, Nixon RM, Wolfe F. Biologic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis in the medicare program: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:939–946. doi: 10.1002/art.23374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solomon DH, Yelin E, Katz JN, Lu B, Shaykevich T, Ayanian JZ. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R43. doi: 10.1186/ar4201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polinski JM, Mohr PE, Johnson L. Impact of Medicare Part D on access to and cost sharing for specialty biologic medications for beneficiaries with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:745–754. doi: 10.1002/art.24560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doshi JA, Li P, Puig A. Impact of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 on utilization and spending for medicare part B-covered biologics in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:354–361. doi: 10.1002/acr.20010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.