Abstract

A growing body of literature suggests that structures along the midline of the prefrontal cortex (mPFC), including Brodmann’s area 32 (prelimbic cortex) and area 24 (anterior cingulate cortex) in the rabbit play a role in retrieval of learned information. The present studies compared the effects of post-training lesions produced either immediately or 1-week following learning, to either prelimbic (area 32) or anterior cingulate (area 24) cortex on trace eyeblink (EB) conditioning. Further, because recent evidence suggests that the mPFC may play an even greater role in learning and memory when emotional arousal is low, these studies compared the effects of lesions in groups conditioned with either a relatively low-arousal corneal airpuff, or a more aversive periorbital eyeshock unconditioned stimulus (US). A total of six groups were tested, which received selective ibotenic acid or “sham” control lesions to either area 32 or 24, immediately or 1-week following asymptotic learning, and conditioned with an eyeshock US or an airpuff US. Results showed that the greatest lesion deficits were found when conditioning with the less aversive airpuff US. Further, lesions produced to area 32 one-week, but not immediately following learning, caused significant deficits in performance, while lesions produced to area 24 immediately, but not 1-week following learning, caused significant deficits in performance. These findings add to the body of evidence which shows that area 32 of the mPFC regulates retrieval, but not acquisition or storage of information, while area 24 mediates a less specific reacquisition process, but not permanent storage or retrieval of information during relearning of memories abolished by mPFC damage. These findings were, however, specific to those experiments in which the relatively non-aversive airpuff was the US.

Keywords: Classical conditioning, Learning, Memory, Prefrontal cortex, Ibotenic acid lesions

1. Introduction

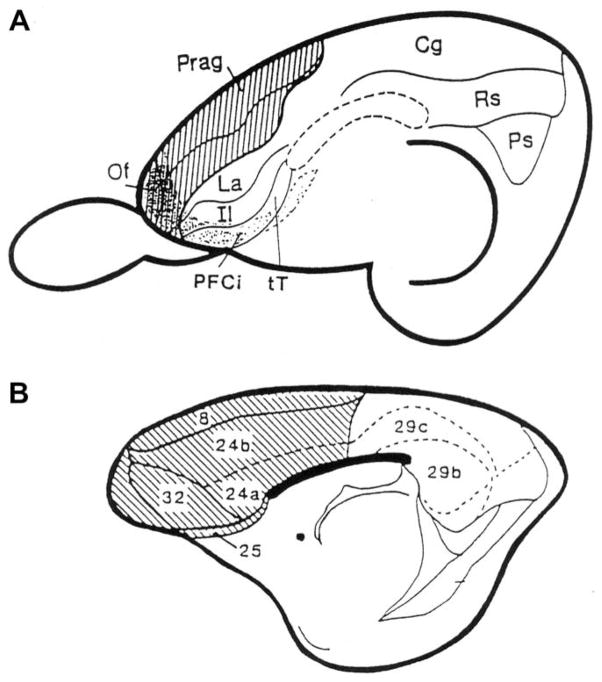

Although it has been known for some time that the prefrontal cortex controls “working memory” (Goldman-Rakic, 1995; Levy & Goldman-Rakic, 2000), recent research suggests that there are distinct structures located along the midline of the PFC (mPFC) that also regulate associative learning, specifically by controlling retrieval of learned information (e.g., Simon, Knuckley, Churchwell, & Powell, 2005; Takehara, Kawahara, & Kirino, 2003). Earlier studies investigated the involvement of select structures within the mPFC including the anterior cingulate (area 24), and prelimbic (area 32) cortices (see Fig. 1) in trace classical eyeblink (EB) conditioning. These studies suggest that the cingulate and prelimbic cortices regulate “higher order” somatomotor mnemonic processes, such as learning to make appropriate somatomotor responses (i.e., the EB conditioned response (CR), under more difficult learning conditions, including trace classical conditioning, differential conditioning, and conditioning under partial or lean reinforcement schedules (Buchanan & Powell, 1982a; Kronforst-Collins & Disterhoft, 1998; McLaughlin, Flaten, Chachich, & Powell, 2001; McLaughlin & Powell, 1996; McLaughlin, Skaggs, Churchwell, & Powell, 2002; Powell, Buchanan, & Gibbs, 1990; Thompson, 2000; Weible, McEchron, & Disterhoft, 2000). Other research has pointed to an important role of these structures in the acquisition of learned autonomic adjustments as well (Buchanan & Powell, 1982a, 1982b; Buchanan, Valentine, & Powell, 1985; Chachich & Powell, 1998; Gibbs, Prescott, & Powell, 1992; Maxwell, Powell, & Buchanan, 1994; Powell, 2006; Powell & Ginsberg, 2005; Powell, McLaughlin, & Chachich, 2000). These studies further confirm the important role of the PFC in associative learning processes. It should be noted however, that damage to these cortical and limbic structures does not impair simple classical delay or discrimination conditioning (Buchanan & Powell, 1982a).

Fig. 1.

(A) The rabbit’s brain lateral view: schematic diagram of the rabbit brain, illustrating the structures comprising the prefrontal cortex. The striped area indicates the portions of the midline PFC from which autonomic responses can elicited by electrical stimulation, including all of the precentral agranular area (Prag) and the more dorsal portions of the anterior limbic area (La). Both of these relatively agranular (or dysgranular) prefrontal areas receive projections from the lateral mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus (MDN), but this projection is much stronger to the more ventral anterior limbic area. The stippled area indicates a three dimensional representation of the lateral orbital and agranular insular areas (PFCi), which also receive projections from the thalamic mediodorsal nucleus, but these projections appear to arise primarily from the medial MDN. Other abbreviations: Cg – posterior cingulate cortex; Re – retrosplenial cortex; Ps – post subicular area; Prag – Precentral agranular area; La – anterior limbic area; Il – infralimbic area; PFU – prefrontal insular cortex; tT– tena tectum; of – orbital frontal cortex. This nomenclature is adapted from Rose and Woolsey (1948). Note that it is somewhat different from that normally used to refer to the architectonic areas of the prefrontal cortex in the rat. (B) Rabbit’s brain medial view: diagram of the medial aspect of the rabbit’s brain showing the Brodmann numbers assigned to the medial prefrontal cortex, based on the work of Vogt, Sikes, Swadlow, and Weyand (1986). The striped area is that part of the prefrontal area which receives the projections of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus and thus comprises the medial part of the agranular prefrontal cortex.

As gleaned from these earlier studies, it appears that several related but functionally distinct brain regions exist along the midline of the PFC which may regulate different mnemonic processes. As a result, more recent work has attempted to elucidate the specific mnemonic process that these select regions control. While learning and memory as a whole obviously requires several integrated structures working in conjunction with each other, it makes sense to try to understand the role that each select structure may play in mediating the explicit processes required for learning and memory, i.e., acquisition, consolidation, storage, and retrieval.

For example, recent evidence suggests that the prelimbic cortex (Brodmann’s area 32) regulates retrieval of learned information (Simon et al., 2005; Takehara et al., 2003), while adjacent areas including the anterior cingulate cortex (Brodmann’s area 24) may regulate acquisition processes (Griffin & Berry, 2004; Konishi, Wheeler, Donaldson, & Buckner, 2000; Lepage, Ghaffar, Nyberg, & Tulving, 2000; Weible, Weiss, & Disterhoft, 2003). The infralimbic cortex (Brodmanns’ area 25) appears to regulate extinction (Corcoran & Maren, 2003; Durrett, Oswald, Maddox, & Powell, 2007; Myers & Davis, 2007; Quirk, Garcia, & Gonzalez-Lima, 2006; Quirk & Mueller, 2007; Robleto, Poulos, & Thompson, 2004).

Takehara and colleagues (2003) found deficits in short-term and long-term memory for the trace EB CR following large ablation lesions to the PFC. We also have published data describing significant deficits in retrieval of the trace EB CR following non-selective electrolytic lesions to the mPFC, focused on area 32 but also including area 24 in most animals, when conditioning with an eyeshock unconditioned stimulus (US, Simon et al., 2005). In this study, five groups of animals were tested: those with post-training lesions produced immediately, 24-h, 1-week, 2-weeks, or 1-month following criterion learning (10 consecutive EB CRs). While animals in each of the five groups were impaired relative to controls, the greatest deficits were observed for animals in the 1-week post-training lesion group. Therefore, because the greatest deficits were observed in animals receiving lesions 1-week following asymptotic performance, we assumed that the information was already processed, and concluded that the 1-week lesions were interfering with a short-term retrieval mechanism.

We followed up that study by looking at the effects of more selective ibotenic acid lesions focused only on area 32, produced 1-week after learning (Oswald, Maddox, & Powell, 2008). Further, because animals in the previous experiments were able to relearn within four retraining sessions, we examined whether animals with area 32 lesions would be impaired after relearning as well. Finally, because animals in our first study had damage to area 24 as well as area 32, we tested separate groups of animals receiving ibotenic acid lesions only to area 24, 1-week following learning. Results indicated that animals sustaining lesions to area 32 one-week following initial acquisition were significantly impaired during retesting days 1–2, but were able to relearn the response within four retraining days. However, when given another week of rest, lesioned animals were again impaired relative to controls at the second re-test period. Animals with lesions focused on area 24 did not exhibit performance deficits at either re-test time. We thus concluded that area 32 regulates a short-term retrieval mechanism for the trace EB CR, while area 24 does not (Oswald et al., 2008).

Further, recent work suggests that the PFC might play a greater role in the acquisition of conditioned responses when the emotional component of the task is low (e.g., Oswald, Knuckley, Mahan, Sanders & Powell, 2006). Therefore, the purpose of the present research was to investigate the nature of the involvement of areas 32 and 24 in recall of a difficult learned associative task, i.e., classical trace eyeblink conditioning in the rabbit, under conditions of low and high emotional arousal. See Table 1 for a summary of these experiments.

Table 1.

Groups tested in the present study. Previously published experiments (Oswald et al., 2008) investigated the effects of lesions to area 32 and area 24 one-week following learning when conditioning with an eyeshock unconditioned stimulus (see shaded areas), and thus are not reported here. Area 32 refers to Brodmann’s area 32, the prelimbic cortex. Area 24 refers to Brodmann’s area 24, the anterior cingulate cortex (see Fig. 1).

| (A) | ||||

| Lesioned area | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Lesion time | Immediate | Immediate | One week | One week |

| Unconditioned stimulus | Airpuff | Eyeshock | Airpuff | Eyeshock |

| (B) | ||||

| Lesioned area | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Lesion time | Immediate | Immediate | One week | One week |

| Unconditioned stimulus | Airpuff | Eyeshock | Airpuff | Eyeshock |

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Subjects were 140 adult (age 2–3 months at the beginning of testing) male and female New Zealand rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), obtained from a local USDA-licensed supplier (Robinson Services Inc., Monksville, NC). Animals were housed in an animal facility accredited by the American Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Animal Laboratory Care International. A 12/ 12 light–dark lighting schedule was used (lights on at 7:00 AM). All behavioral testing occurred during the light portion of the cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All procedures were conducted in accordance with United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) regulations and standards regarding animal welfare.

2.2. Surgery

All stereotaxic surgery was performed under aseptic conditions, under general anesthesia, using a combination of ketamine hydrochloride (55 mg/kg, i.m.), acepromazine maleate (2.2 mg/kg, i.m.) and xylazine (4.4 mg/kg, i.m.) as anesthetics. Rabbits were positioned in a Kopf stereotaxic instrument, equipped with a rabbit head holder. A small portion of the skull above the prefrontal cortex was removed with a dental drill, and the dura mater slit in order to allow for insertion of a 10 μl Hamilton microsyringe (30 g needle). Lesions were made by injection of ibotenic acid (Sigma), dissolved in 7.4 pH buffered saline. Each injection consisted of 0.5 μl, i.e., 5 μg, injected over a 2 min period and allowed to diffuse for 2 min before the syringe was retracted. Such injections destroy cell bodies in a 0.5–2 mm region, without affecting fibers of passage (Buchanan, 1988). For studies of Brodmann’s area 32 (n = 76), the needle of the Hamilton syringe was stereotaxically lowered into the brain to deliver bilateral injections at coordinates AP +7.0 and 9.0; L ±0.5; and DV −3.0, −4.5 and −3.5, −4.5, relative to bregma, the midline sinus, and dura, respectively. For studies of Brodmann’s area 24 (n = 64), coordinates were AP +1, 3, 5, 7, and 9; L ±0.5; and DV −3.0. Animals with sham lesions received identical surgery but were injected with only buffered saline.

2.3. Apparatus and procedure

Experimental contingencies and EB responses were controlled and recorded by a PC-based data acquisition system (MACRO, Inc., Columbia, SC), supplemented by solid state transistor–transistor logic (TTL) programming devices. The EB responses were also recorded on a Grass Model 7 polygraph (Astro-Med, Inc., West Warwick, RI) equipped with EMG preamplifiers. During conditioning, the output of the polygraph was connected to the computer where A–D conversion was performed in real time. The CS was a 500 ms duration, 1200 Hz, 75-dB tone. Either a 100 ms, 3 mA AC (200 Hz) electric shock train, or 3.5 psi, 100 ms airpuff, served as the US. The shock US was delivered by a Grass Model S88 stimulator (Astro-Med, Inc., West Warwick, RI) equipped with constant current and stimulus isolation units, and was administered periorbitally through two previously implanted stainless steel wound clips placed above and below the rabbit’s right eye. The airpuff US was delivered via a pressurized airsource carried through Tygon tubing oriented 1 mm in front of the rabbit’s right orbit. During the experiment, animals were restrained in Plexiglas rabbit restrainers (Gormezano, 1966), in ventilated, sound- and light-attenuating commercial animal enclosures (Industrial Acoustics Co., Bronx, NY). Each session consisted of 100 trials with a 22(±5) s intertrial interval (ITI). The EB response was measured via electrodes consisting of Tru-chrome dental wire acutely inserted under the eyelids before the beginning of each session. Insertion of these electrodes caused neither apparent discomfort nor any signs of infection or irritation. Leads for the EB electrodes were connected to a Grass Model 7P3 preamplifier and integrator set in its integrator mode. The preamplifier was calibrated so that a 0.10 V change across the electrodes corresponded a 0.5 mm movement of the eyelids. During conditioning, the EB response was recorded by the A–D converter of the computer, which sampled at 1000 Hz beginning 4 s before tone onset and continuing for 3 s following US offset.

For behavioral testing, each animal received two initial habituation sessions in which they were loosely restrained in the chamber, but no stimuli were presented. These two sessions were followed by daily sessions of trace conditioning in which the CS was presented paired with the US, but with a 500 ms interval separating CS termination and US onset. Training continued for either 10 consecutive days (airpuff studies) or until animals achieved criterion of 10 consecutive EB CRs (periorbital eyeshock studies; an average of 2.3 training days). Surgery occurred either immediately (1–6 h) or 1-week following training. All animals were allowed a 1-week post-surgical recovery period, and were retested on the trace conditioning task for four consecutive days. Following retraining, animals were given a 1-week rest period in their home cages, prior to retesting again on the trace conditioning task for four consecutive days.

2.4. Histology

After behavioral testing was completed, animals were sacrificed with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with physiological saline and 10% formalin. The brain was removed, quick-frozen in 2-methylbutane, and sliced in the coronal plane in a cryostat. Forty μm sections were taken through the lesion sites and stained with thionin. The lesions were then located microscopically and line drawings made of the appropriate sections using a Leitz drawing tube and microscope. The extent of the lesion was then determined by superimposing these drawings onto plates from the atlas of Shek, Wen, and Wisniewski (1986).

2.5. Data reduction and analysis

The criterion for an EB CR was a 0.10 V change from baseline during CS presentation or the trace period, with a latency of greater than 100 ms. CR latency was recorded as the time from CS onset until the EB response first exceeded criterion. EB CRs with a latency of less than 100 ms were considered alpha responses (i.e., reflex responses to the tone) and were discarded (Kimble, 1961); fewer than 5% of responses were discarded for this reason. CR amplitude was recorded as the maximum amplitude change (in millivolts) from baseline during the CS/US period. Further, in order for an animal in any of the airpuff conditions to be included further (viz., surgery, retraining or data analyses), they had to show EB CRs on at least 40% of the trials on any single pre-training session. We chose this a priori criterion based on our research demonstrating that occasionally, even young, healthy rabbits have difficulty acquiring EB CRs even after extensive training (up to 1500 trials) with an airpuff US. We expected that 10–15% of animals trained with an airpuff US would fail to meet this criterion. An a priori criterion was also established for animals in the eyeshock groups, to reach the criterion of 10 consecutive EB CRs within 400 trials (four daily 100-trial sessions). We expected that less than 1% of animals trained with an eyeshock US would fail to meet this criterion.

Separate two-way ANOVAs (i.e., sham/lesion × session) were used to compare pre-training performance in the groups trained with the airpuff US, while separate one-way ANOVAs were used to compare the number of trials to criterion in the eyeshock groups. Separate two-way mixed analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with sham/lesion as a between-subjects factor and session as a repeated measure, were used to compare the effects of lesioned and sham-operated controls in each of the lesion groups (area 32 or area 24) and US groups (airpuff or eyeshock) over each of the post-training sessions (viz., post-training sessions 1–4 and post-training sessions 5–8). The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used to control for sphericity on the repeated factor (Greenhouse & Geisser, 1959). Duncan’s Multiple Range test was used post-hoc when the overall ANOVAs were significant. Finally, separate three-way (lesion × session × trial) ANOVAs compared amplitude and latency data between each of the groups (lesion location and US type). However, in most of these analyses the group effect was either not significant, or showed the same effects as the percent CR measure. Thus, only analyses for percent CRs are reported in the description of the results below.

3. Experiment 1: prelimbic cortex (area 32)

3.1. Groups

There were a total of three groups receiving lesions to Brodmann’s area 32 (prelimbic cortex): an immediate post-training lesion group trained with an airpuff US (n = 20), an immediate post-training lesion group trained with an eyeshock US (n = 20), and a 1-week post-training lesion group trained with an airpuff US (n = 36). Note that, as explained above, data from a 1-week post-training group trained with an eyeshock US was reported in a previous paper (Oswald et al., 2008).

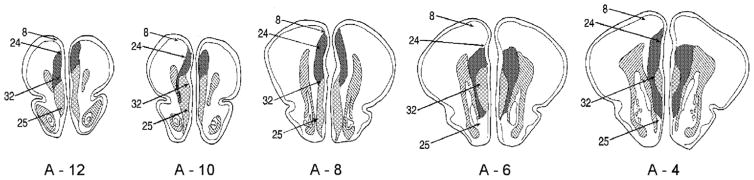

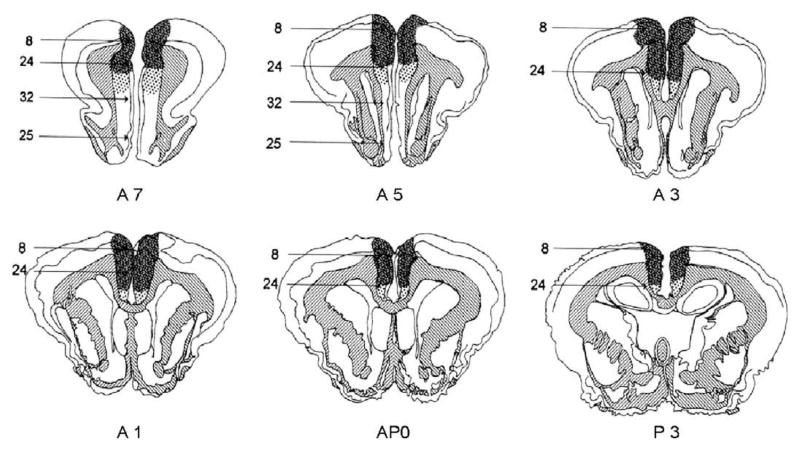

3.2. Histology

Histological analyses revealed lesions that were too large, incomplete, or unilateral in: (a) one animal in the immediate lesion eyeshock group and (b) four animals in the 1-week airpuff group; their data were thus not included in further analyses. Fig. 2 shows diagrams through the mPFC of the rabbit’s brain showing the maximal (light stippling) and minimal (dark stippling) damage to the mPFC for all animals included in the data analyses. The Brodmann’s areas of the region are also indicated. As seen in Fig. 2, the damage in lesioned animals in all three prelimbic groups was focused on Brodmann’s area 32, with minimal damage to adjacent areas.

Fig. 2. Damage to prelimbic cortex.

diagrams of frontal sections through the rabbit’s brain, showing maximal (striped) and minimal (stippled) damage to the prelimbic area of the prefrontal cortex in the present experiments. Appropriate coordinates are shown, based on the Atlas of Shek et al. (1986). Brodmann numbers, based on the nomenclature of Vogt et al. (1986) are as follows: area 8, prefrontal eyefields; area 24, cingulate cortex; area 32, prelimbic area; and area 25, infralimbic area.

3.2.1. Conditioning with airpuff US; immediate post-training lesion

3.2.1.1. Animals

Seven animals were discarded for not meeting the a priori criterion of at least 40% EB CRs in a single session (see Section 2), and (as noted above) data from one animal was discarded due to a poorly placed lesion. Thus a total of 12 animals were included in the analyses for this group, five lesioned and seven sham.

3.2.1.2. Pre-training data

An ANOVA on the percentage of EB CRs across the 10 trace conditioning sessions prior to lesion surgery indicated no significant differences in acquisition rate between lesioned and sham animals [F(1,10) = 0.20, p > 0.05], but a significant session effect [F(9,90) = 2.79, p < 0.006] with no interaction [F(9,90) = 0.74, p > 0.05], indicating that animals in both groups learned over conditioning days to an equal degree (see Fig. 3, left panel).

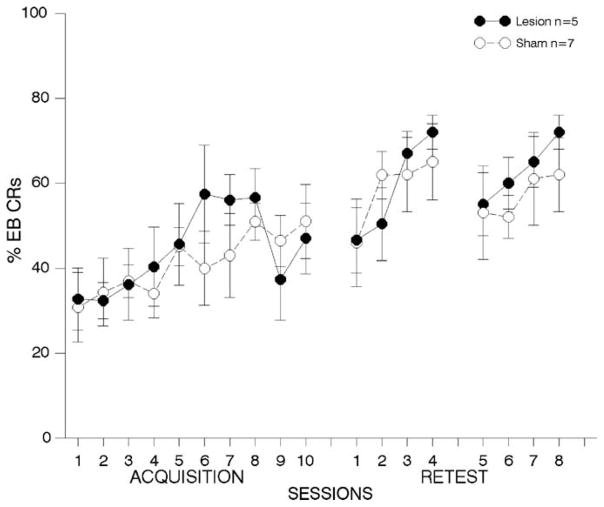

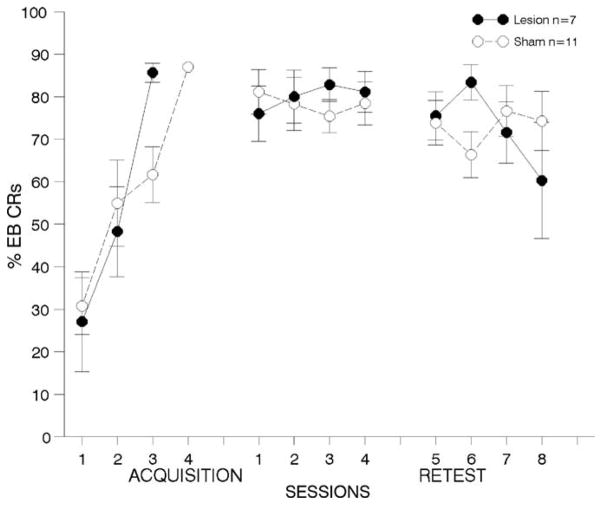

Fig. 3. Immediate lesions to prelimbic cortex; airpuff US.

results from behavioral tests with animals receiving lesions to Brodmann’s area 32 (prelimbic cortex) immediately following trace eyeblink (EB) conditioning using an airpuff unconditioned stimulus (US). Left panel indicates initial acquisition (conditioning days, sessions 1– 10), middle panel contains data from the first re-test period, that began 1-week following recovery from surgery and lasted for four consecutive days (sessions 1–4), and the right panel depicts data from the second retraining period, 1-week following the end of the first retraining period (sessions 5–8). There were no significant differences between lesioned and non-lesioned animals during pre-training or either of the retraining periods.

3.2.1.3. First post-training re-test period

Fig. 3, middle panel shows results from behavioral tests conducted during the first re-test period. An ANOVA on the percentage of EB CRs revealed no significant deficits in performance for lesioned animals [F(1,10) = 0.00, p > 0.05], but a significant session effect [F(3,30) = 4.67, p < 0.03], with no lesion × session interaction (see Fig. 3).

3.2.1.4. Second post-training re-test period

An ANOVA comparing performance in lesioned versus sham-operated controls revealed no significant differences in performance across retraining sessions 5–8 [F(1,10) = 0.62, p > 0.05]; see right hand panel of Fig. 3. Also, the session effect had disappeared by this retraining period [F(3,30) = 2.18, p > 0.05], and there was no lesion × session interaction effect, suggesting that animals did not learn to perform any better over this second week of training days. An evaluation of the means revealed that performance began high for both groups on retraining day 5 (~55%) and remained high throughout the four retraining days (65–72%).

3.2.2. One-week post-training lesion

3.2.2.1. Animals

For animals with 1-week post-training lesions nine animals failed to meet criterion, four animals had poorly placed lesions, and one animal in the sham group became ill during retesting, leaving a total of 18 animals (10 lesion and eight sham) to be included in the behavioral analyses.

3.2.2.2. Pre-operative training data

As expected, the ANOVA on the percentage of EB CRs across the 10 trace conditioning days prior to surgery indicated no significant group differences [F(1,16) = 1.70, p > 0.05], but a highly significant session effect [F(9,144) = 5.86, p < 0.001], indicating that animals learned over conditioning days (see Fig. 4, left panel).

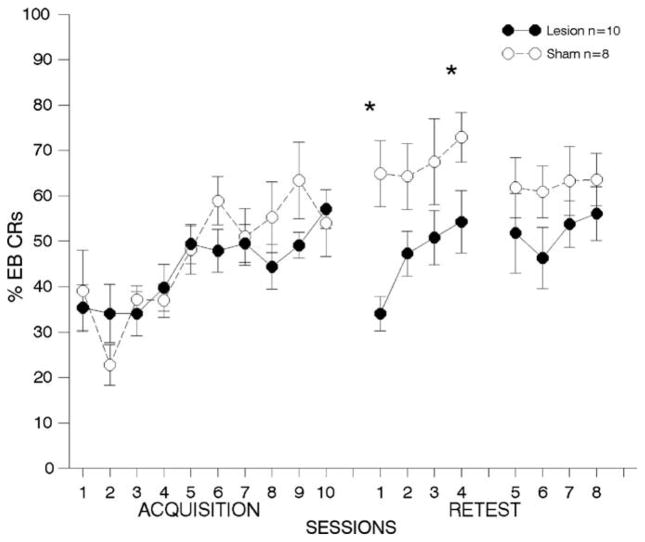

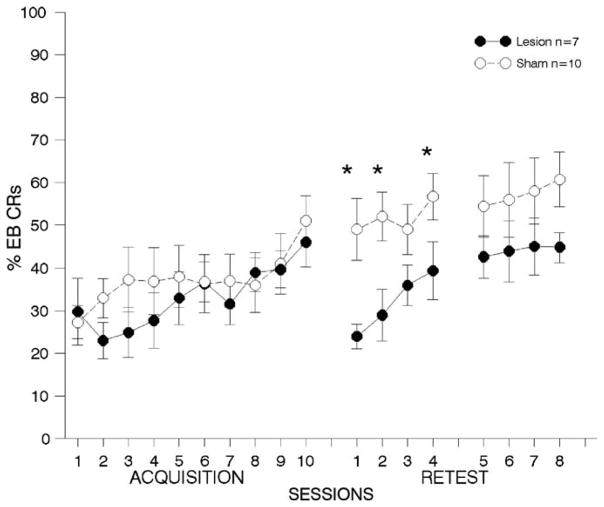

Fig. 4. One week lesions to prelimbic cortex; airpuff US.

results from behavioral tests with animals receiving lesions or sham surgeries to area 32, one-week following trace EB conditioning with an airpuff US. Details are the same as in Fig. 3. There were no differences between the groups in pre-training performance, but lesioned animals were significantly impaired throughout the first one-week post-training test period. Lesioned animals continued to perform more poorly during the second post-training test period, although these effects were not significantly different from animals with sham lesions. (*p < 0.05).

3.2.2.3. First post-training re-test period

Fig. 4, middle panel shows results from behavioral tests conducted during the first re-test period. The ANOVA on the percentage of EB CRs revealed significant deficits in performance for lesioned compared to sham animals [F(1,20) = 6.89, p < 0.02]. Post-hoc analyses revealed significant differences on retraining days 1 and 4 (see Fig. 4).

3.2.2.4. Second post-training re-test period

Although lesioned animals failed to perform as well as sham controls over retraining days 5–8 (see Fig. 4, right panel), the ANOVA comparing performance between lesioned and sham-operated controls failed to reveal significant differences in the percentage of EB CRs in lesioned compared to sham animals [F(1,16) = 2.11, p > 0.05].

3.2.3. Conditioning with an eyeshock US; immediate post-training lesion

3.2.3.1. Histology

Histological analyses revealed that two animals had incomplete lesions, leaving a total of 18 animals (seven lesion and 11 sham) included in the analyses.

3.2.3.2. Pre-operative training data

Fig. 5 shows results from behavioral tests in this group. A one-way ANOVA performed on the number of trials to criterion revealed, as expected, no significant differences between the groups, with an average of 175.7 trials required for animals that later received lesions, and an average of 171.7 trials to criterion for animals that later received sham surgeries [F(1,16) = 6.84, p > 0.05).

Fig. 5. Immediate lesions to prelimbic cortex; eyeshock US.

results from behavioral tests with animals receiving lesions to area 32 immediately following conditioning on a trace EB conditioning task, utilizing an eyeshock US. Details are the same as in Fig. 3, except the left panel depicts the average percentage of EB CRs exhibited over four pre-training days, the maximum number of days required for any animal to reach a criterion of 10 consecutive EB CRs.

3.2.3.3. First post-training re-test period

An ANOVA comparing post-training performance between lesioned and sham animals revealed no significant lesion [F(1,16) = 0.13, p > 0.05] or session effects [F(3,48) = 0.02, p > 0.05], and no interaction (see Fig. 5, middle panel). As can be seen in Fig. 5, performance started out high in both groups and remained high over all four retraining sessions. Thus, lesioned animals were not impaired across retraining days.

3.2.3.4. Second post-training re-test period

Likewise, the ANOVA comparing the percentage of EB CRs during the second re-test period also revealed no significant lesion or session main effects; the interaction also was not significant [F(3,48) = 2.23, p = 0.1003; see Fig. 5].

3.3. Discussion

Results indicate that damage to Brodmann’s area 32 (prelimbic cortex) 1 week, but not immediately following learning, resulted in performance deficits. These findings provide additional evidence that the prelimbic portion of the PFC functions to mediate a retrieval mechanism. Further, performance deficits occurred only when animals were conditioned with a less aversive airpuff stimulus, rather than a more aversive eyeshock US. These findings are in agreement with other studies noting that the PFC may play a greater role in learning and memory when emotional arousal is low, e.g., Oswald et al. (2006).

The fact that post-training lesions produced 1-week following learning caused deficits in the percentage of EB CRs during retesting are in agreement with other findings noting a role for the PFC in a short-term retrieval process (e.g., Simon et al., 2005; Takehara et al., 2003). However, the fact that: (1) the highly selective lesions produced immediately following acquisition in the present experiments did not disrupt performance, and (2) animals with prelimbic lesions were able to relearn the task within four retraining sessions, leaves open the question of what brain area regulates reacquisition after PFC damage. Based on results from our previous study (Oswald et al., 2006) in which animals sustaining large lesions encompassing prelimbic and anterior cingulate cortex immediately and up to 6 h following learning showed acquisition deficits, we investigated the effects of post-training lesions to the anterior cingulate cortex alone, either immediately or 1-week following learning.

4. Experiment 2: anterior cingulate cortex (area 24)

4.1. Groups

There were a total of three groups receiving lesions to Brodmann’s area 24 (anterior cingulate cortex): an immediate post-training lesion group trained with an airpuff US (n = 32), an immediate post-training lesion group trained with an eyeshock US (n = 16), and a 1-week post-training lesion group trained with an airpuff US (n = 16).

4.2. Animals and histology

Histological analyses revealed that lesions were too large, incomplete, or unilateral in one animal in the immediate lesion airpuff group, and one animal in the immediate lesion shock group. These data were thus not included in the behavioral analyses. Fig. 6 shows diagrams through the mPFC of the rabbit’s brain showing the maximal (light stippling) and minimal (dark stippling) damage to the mPFC for all animals included the in the data analyses. The Brodmann’s areas of the region are also indicated. As can be seen in Fig. 6, the damage in lesioned animals in all three anterior cingulate groups was focused on Brodmann’s area 24, with minimal damage to adjacent areas.

Fig. 6. Anterior cingulate damage.

diagram of frontal sections through the rabbit’s brain illustrating damage produced to the anterior cingulate region (area 24) of the prefrontal cortex in the present experiments. Maximal damage is indicated by loose stippling and minimal damage (common to all animals) is indicated by tight stippling. Approximate coordinates are illustrated, based on the Atlas of Shek et al. (1986). Brodmann numbers are also indicated, as defined in Fig. 2.

4.2.1. Immediate post-training lesion: airpuff US

4.2.1.1. Animals

Of the 32 animals, six failed to meet our a priori criterion of at least 40% EB CRs in a single session (see Section 2), five died following surgery, three became ill unrelated to surgery, and one had a poorly placed lesion (as noted above), leaving a total of 17 animals in the analyses, seven lesion and 10 sham.

4.2.1.2. Pre-operative training data

Fig. 7 shows behavioral data across all pre- and post-training conditioning sessions. As expected, the ANOVA on the percentage of EB CRs over the 10 pre-operative trace conditioning sessions revealed no significant differences between the groups in pre-operative performance [F(1,15) = 2.08, p = 0.17], but a significant effect of session [F(9,135) = 4.34, p < 0.0001], with no group × session interaction [F(9,135) = 0.86, p = 0.57].

Fig. 7. Immediate lesions to anterior cingulate cortex; airpuff US.

results from behavioral tests with animals receiving lesions to Brodmann’s area 24 (anterior cingulate cortex) immediately following trace eyeblink (EB) conditioning using an airpuff unconditioned stimulus (US). Details are the same as Fig. 3. (*p < .01).

4.2.1.3. First post-training re-test period

As can be seen in Fig. 7 middle panel, the ANOVA on the percentage of EB CRs during retraining days 1–4 revealed a highly significant lesion effect, with lesioned animals failing to perform to the same extent as animals with sham lesions [F(1,15) = 10.52, p < 0.005]. There was a significant session effect [F(3,45) = 4.39, p < 0.008] but no lesion × session interaction, suggesting that lesioned animals were able to relearn over the four retraining sessions, although post-hoc tests indicated that animals with lesions performed significantly worse except for the third retraining day (see Fig. 7).

4.2.1.4. Second post-training re-test period

Lesioned animals appeared to continue to perform more poorly throughout the second retraining period; see Fig. 7. However, the ANOVA on the percentage of EB CRs between lesioned and sham animals across retraining days 5–8 revealed no significant lesion [F(1,15) = 3.22, p = .095] or session effects [F(3,45) = 0.53, p = 0.62], and no interactions[ F(3,45) = 0.15, p = 0.89].

4.2.2. One week post-training lesion, airpuff US

4.2.2.1. Animals

There were 16 animals randomly assigned to this group, two animals failed to meet our a priori criterion of at least 40% EB CRs in a single session, two animals died during behavioral testing, and one lesioned animal had a poorly placed lesion, leaving a total of five lesioned and six sham animals included in the behavioral data analyses.

4.2.2.2. Pre-operative training data

As expected, there were no significant differences between animals later receiving mPFC lesions and those later receiving sham lesions during the 10 pre-operative trace conditioning sessions [F(1,9) = 0.41, p = 0.54]; see Fig. 8. There was a significant effect of session [F(9,81) = 8.65, p < 0.001], but no lesion × session interaction [F(9,81) = 1.34, p = 0.25], demonstrating that animals learned, to an equal degree, over the 10 training sessions.

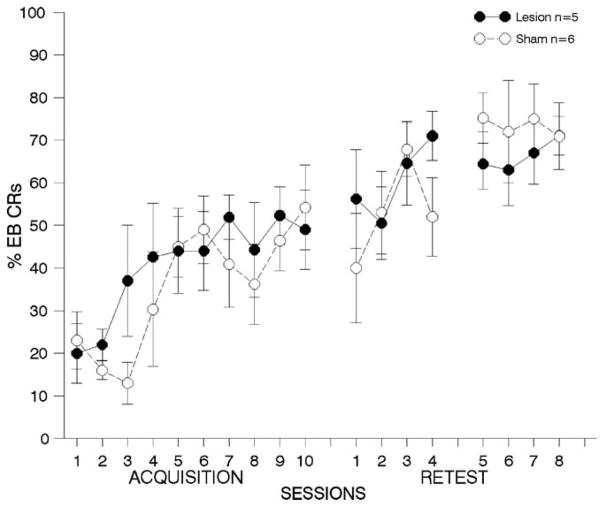

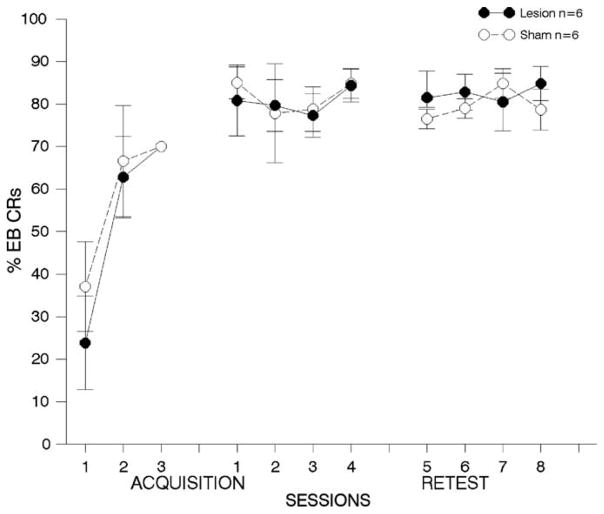

Fig. 8. One week lesions to anterior cingulate cortex; airpuff US.

results from behavioral tests with animals receiving lesions to Brodmann’s area 24 (anterior cingulate cortex) 1-week following trace eyeblink (EB) conditioning with an airpuff US. Details are the same as Fig. 3.

4.2.2.3. First post-training re-test period

As can be seen in Fig. 8 middle panel, there was no difference between the groups during retraining days 1–4 [F(1,9) = 0.66, p = 0.44], although there was again a significant effect of session [F(3,27) = 3.09, p < 0.04], with no lesion × session interaction [F(3,27) = 1.55, p = 0.23], suggesting that both groups continued to improve to an equal degree over the four retraining days.

4.2.2.4. Second post-training re-test period

The ANOVA comparing the percentage of EB CRs during the second retraining period revealed no significant lesion or session effects, and no interactions (all p’s > 0.05; see Fig. 8, right panel).

4.2.3. Immediate post-training lesion, eyeshock US

4.2.3.1. Animals

Of the 16 animals randomly assigned to this group, two shams became ill prior to or during behavioral testing, one lesioned animal died following surgery, and data from one lesioned animal was discarded due to a misplaced lesion, leaving a total of 12 animals (six lesioned and six sham) included in the data analyses.

4.2.3.2. Pre-operative data

A one-way ANOVA of the trials required to reach criterion indicated that there was no significant difference between the groups; animals that later received lesions took an average of 150.33 trials to reach criterion, and animals that later received “sham” surgeries required an average of 145.17 trials to reach criterion (p < 0.05).

4.2.3.3. First post-training re-test period

Fig. 9 shows the percentage of EB CRs over the pre-training and post-training periods from the 12 animals included in the analyses. Unlike that found with immediate area 24 lesions when conditioning with an airpuff US, the ANOVA comparing the percentage of EB CRs during the first 4 days of retraining in animals conditioned with an eyeshock US revealed no significant lesion [F(1,10) = 0.05, p = 0.83] or session effects [F(3,30) = 0.64, p = 0.54], and no interactions [F(3,30) = 0.10, p = 0.91]).

Fig. 9. Immediate lesions to anterior cingulate cortex; eyeshock US.

results from behavioral tests with animals receiving lesions to Brodmann’s area 24 (anterior cingulate cortex) immediately following trace eyeblink (EB) conditioning using an eyeshock unconditioned stimulus (US). Details are the same as Fig. 3.

4.2.3.4. Second post-training re-test period

The ANOVA comparing the percentage of EB CRs during the second retraining period also yielded no significant lesion or session effects, and no interactions (all p’s > 0.05; see Fig. 9).

4.3. Discussion

Results from the present experiments investigating the effects of lesions to the anterior cingulate cortex (Brodmann’s area 24) indicate that lesions produced immediately but not 1-week following learning resulted in performance deficits. As found in previous experiments (e.g., Oswald et al., 2006), lesion-induced deficits were even more pronounced when conditioning with a less aversive airpuff US. These findings suggest that the anterior cingulate cortex provides a mechanism by which newly-acquired information is processed, at least when that information is not highly emotional.

5. General discussion

The results of the present experiments demonstrate that post-training lesions to the mPFC result in differential memory deficits as a function of the specific region of mPFC that is involved, as well as the type of unconditioned stimulus that is used during learning. These findings are in agreement with others, who have used less selective lesions (Simon et al., 2005; Takehara et al., 2003).

However, despite initial performance deficits, post-training lesions to the mPFC did not disrupt the ability to relearn and restore information, as exhibited by the performance increases in the lesioned groups throughout the retesting periods. These results suggest that area 32 of the mPFC provides a retrieval mechanism for eliciting the CR, but does not participate in either storage or acquisition. It is important to note that the lesioned animals showed steady relearning throughout the first 4-day retesting period and also that this heightened performance level was sustained through the 1-week rest period and continued into the second retraining period. This finding suggests that there must be some other circuitry fostering retrieval processes in the absence of the mPFC. It is likely that initial learning fosters a network between the PFC and storage sites (i.e., cerebellum). However, in the absence of the PFC (viz., during relearning in the present study), new connections are strengthened elsewhere. The hippocampus is one likely target for these new connections because of its extensive connections to the mPFC and the anterior cingulate cortex (Bassett & Berger, 1982; Vogt, Sikes, Swadlow, & Weyand, 1986). Indeed, it has been suggested that without PFC input, the hippocampus becomes necessary in the retrieval and reacquisition of previously stored memories (Debiec, LeDoux, & Nadar, 2002; Takehara et al., 2003). However, the results of these studies may have been due to damage to the storage site for the consolidated memories, since aspiration lesions were employed. Also neither study tested the requirement of the hippocampus for memory of the task in the absence of the PFC. Thus, further studies will be necessary to clarify the interaction between the PFC and the hippocampus in the retrieval of previously stored information.

It has been shown in a variety of contexts that the prefrontal cortex in rodents and rabbits, which have typically included Brodmann’s areas 24 and 32, is not a homogenous area. Not only do to the architectonics of area 24 and 32 differ, but input/output connections are also different (Buchanan, Powell, & Thompson, 1989; Buchanan, Thompson, Maxwell, & Powell, 1994; Domesick, 1972; Rose & Woolsey, 1948). A variety of evidence also exists suggesting that this area of the brain is involved in mediating associative learning (see Powell (2006) for a recent review). Several studies have shown that acquisition of autonomic changes during classical conditioning are impaired as a function of prefrontal damage (e.g., Buchanan & Powell, 1982a, 1982b; Powell, Watson, & Maxwell, 1994; Powell et al., 1990, 2000). As described earlier, more recent studies have shown that acquisition of the somatomotor classically conditioned trace, but not delay eyeblink response is also impaired as a function of prefrontal damage (e.g., McLaughlin et al., 2002; Weible et al., 2000). The present data show that separate functions are mediated by areas 24 and 32 as well. Large post-training lesions of area 24 made immediately after training produced performance deficits of the eyeblink CR, whereas lesions produced 1 week later had no effect. Thus, we conclude that area 24 is involved in the initial acquisition and/or consolidation of information in classical eyeblink conditioning. On the other hand, post-training damage to area 32, the prelimbic cortex, significantly impaired performance of the eyeblink CR only if the lesion was produced 1-week following training, suggesting that area 32 is involved in either storage or retrieval of learned information. However, the finding in Oswald et al. (2006) that performance was also impaired on a second week of retesting suggests that area 32 is involved in retrieval rather than storage or consolidation.

It should be stressed, however, that these effects were produced only when an airpuff was employed as the unconditioned stimulus. When periorbital shock was employed as the unconditioned stimulus, performance deficits did not occur. We have assumed that a 3 mA, 100 ms eyeshock is more aversive than the presentation of a 100 ms, 3 psi airpuff, and there are a host of data to support this conclusion (e.g., Powell, Gibbs, Maxwell, & Levine-Bryce, 1993; Powell, Maxwell, & Penney, 1996). If this is the case, the discrepancy between the airpuff findings and periorbital shock findings may be related to inputs from amygdala to the mPFC in the more aversive eyeshock conditions, but such input may be minimal or non-existent when the less aversive airpuff is employed as the US. This hypothesis needs to be further tested, however.

These data may explain a number of inconsistencies previously reported in the literature with regard to prefrontal control of eye-blink conditioning; viz., whereas some studies have shown deficits in acquisition or performance others have not. However, in these various studies the US has at times been an airpuff US and in other studies an eyeshock US. The present data are very clear in showing that using periorbital shock as the US does not result in deficits in post-training performance, whereas the utilization of the airpuff US does in all cases, if administered at an appropriate interval following training. It is important to note that this impairment was deemed to be due to a deficit in retrieval, as opposed to storage or consolidation. These findings are very similar to those of a previous study in which it was demonstrated that ibotenic acid lesions, limited to area 32, produced retrieval deficits (Oswald et al., 2008). The present study confirms these findings.

We believe these findings are extremely relevant to understanding the role that different prefrontal structures play in association formation. It is of some importance to parcel out the different structures in the brain that mediate various aspects of learning and memory, which as noted above, is a relatively complex process. The identification of structures that are differentially involved in acquisition versus retrieval is an important finding and can be related to possible mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders; for example, it has been shown that prefrontal connections to the amygdala are intimately involved in the preservative responses shown in post-traumatic stress disorder (Bremner, Krystal, Southwick, & Charney, 1995). Similarly, aberrations in prefrontal function have been related to symptoms of schizophrenia (Hécaen, 1964; Benes, 1993). Clearly, understanding the nature of the role that these different structures in prefrontal cortex play in acquisition and performance of learned associative behaviors may be relevant to the treatment and diagnosis of these disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research funds awarded to the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Columbia, SC. We thank Elizabeth Hamel for manuscript preparation and Andrew Pringle, Jr. for assistance with preparation of the illustrations.

References

- Bassett JL, Berger TW. Associational connections between the anterior and posterior cingulated gyrus in rabbit. Brain Research. 1982;248:371–376. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90597-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM. Relationship of cingulate cortex to schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders. In: Vogt BA, Gabriel M, editors. Neurobiology of cingulate cortex and limbic thalamus. Boston, MA: Birkhauser; 1993. pp. 581–605. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Charney DS. Functional neuroanatomical correlates of the effects of stress on memory. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:527–553. doi: 10.1007/BF02102888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL. Mediodorsal thalamic lesions impair differential Pavlovian heart rate conditioning. Experimental Brain Research. 1988;73:320–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00248224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL, Powell DA. Cingulate cortex: Its role in Pavlovian conditioning. Journal of Comparative Physiological Psychology. 1982a;96:755–774. doi: 10.1037/h0077925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL, Powell DA. Cingulate damage attenuates conditioned bradycardia. Neuroscience Letters. 1982b;29:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL, Powell DA, Thompson RH. Prefrontal projections to the medial nuclei of the dorsal thalamus in the rabbit. Neuroscience Letters. 1989;106:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL, Thompson RH, Maxwell BL, Powell DA. Efferent connections of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rabbit. Experimental Brain Research. 1994;100:469–483. doi: 10.1007/BF02738406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SL, Valentine JD, Powell DA. Autonomic responses are elicited by electrical stimulation of the medial but not lateral frontal cortex in rabbits. Behavioural Brain Research. 1985;18:51–62. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(85)90168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chachich M, Powell DA. Both medial prefrontal and amygdala central nucleus lesions abolish heart rate classical conditioning, but only prefrontal lesions impair reversal of eyeblink differential conditioning. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;257:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00832-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Maren S. Reversible inactivation of medial prefrontal cortex disrupts the retrieval of fear extinction. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2003 Program no. 199.8. [Google Scholar]

- Debiec J, LeDoux JE, Nadar K. Cellular and systems reconsolidation in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2002;36:527–538. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domesick VB. Thalamic relationships of the medial cortex in the rat. Brain Behavior and Evolution. 1972;6:457–483. doi: 10.1159/000123727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrett S, Oswald BB, Maddox SA, Powell DA. “Reversible” lesions with muscimol into infralimbic cortex (Area 25) disrupt extinction but not acquisition of a trace conditioned eyeblink response. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2007;33 Program no. 306.2. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs CM, Prescott LB, Powell DA. A comparison of multiple-unit activity in the medial prefrontal and agranular insular cortices during Pavlovian heart rate conditioning in rabbits. Experimental Brain Research. 1992;89:599–610. doi: 10.1007/BF00229885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS. Architecture of the prefrontal cortex and the central executive. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 1995;769:71–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb38132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormezano I. Classical conditioning. New York: McGraw Hill; 1966. pp. 385–420. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse SW, Geisser S. On methods in the analysis of profile data. Psychometrika. 1959;24:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin AL, Berry SD. Inactivation of the anterior cingulate cortex impairs extinction of rabbit jaw movement conditioning and prevents extinction-related inhibition of hippocampal activity. Learning and Memory. 2004;11:604–610. doi: 10.1101/lm.78404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hécaen H. Mental symptoms associate with tumors of the frontal lobe. In: Warren JM, Akert K, editors. The frontal granular cortex and behavior. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1964. pp. 335–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kimble GA. Hilgard and Marquis’ conditioning and learning. New York: Appelton-Century-Crofts; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi S, Wheeler ME, Donaldson DI, Buckner RL. Neural correlates of episodic retrieval success. Neuroimage. 2000;12:276–286. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronforst-Collins MA, Disterhoft JF. Lesions of the caudal area of rabbit medial prefrontal cortex impair trace eyeblink conditioning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 1998;69:147–162. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1997.3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage M, Ghaffar O, Nyberg L, Tulving E. Prefrontal cortex and episodic memory retrieval mode. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 2000;97:506–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Goldman-Rakic PS. Segregation of working memory functions within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Experimental Brain Research. 2000;133:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s002210000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell B, Powell DA, Buchanan SL. Multiple- and single-unit activity in area 32 (prelimbic region) of the medial prefrontal cortex during Pavlovian heart rate conditioning in rabbits. Cerebral Cortex. 1994;4:230–246. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J, Flaten MA, Chachich M, Powell DA. Medial prefrontal lesions attenuate conditioned reflex facilitation but do not affect prepulse modification of the eyeblink reflex in rabbits. Experimental Brain Research. 2001;140:318–325. doi: 10.1007/s002210100833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J, Powell DA. Lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex and appetitive jaw movement conditioning in the rabbit. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1996;22:1647. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J, Skaggs H, Churchwell J, Powell DA. Medial prefrontal cortex and Pavlovian conditioning: Trace versus delay conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116:37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Davis M. Mechanisms of fear extinction. Molecular Psychiatry. 2007;12:120–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald BB, Knuckley B, Mahan K, Sanders C, Powell DA. Prefrontal control of trace versus delay eyeblink conditioning: Role of the unconditioned stimulus in rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120:1033–1042. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.5.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald BB, Maddox SA, Powell DA. Prefrontal control of trace eyeblink conditioning in rabbits II: Role in retrieval of the CR. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;122:841–848. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DA. Medial prefrontal cortex and pavlovian conditioning. Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;2:1–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DA, Buchanan SL, Gibbs CM. Role of the prefrontal–thalamic axis in classical conditioning. In: Uylings HBM, Eden CGV, Bruin JPCD, Corner MA, Feenstra MGP, editors. The prefrontal cortex: Its structure function and pathology progress in brain research. Vol. 85. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers BV; 1990. pp. 433–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DA, Gibbs CM, Maxwell B, Levine-Bryce D. On the generality of conditioned bradycardia in rabbits: Assessment of cs and us modality. Animal Learning and Behavior. 1993;21:303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Powell DA, Ginsberg JP. Single unit activity in the medial prefrontal cortex during Pavlovian heart rate conditioning: Effects of peripheral autonomic blockade. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2005;84:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DA, Maxwell BL, Penney JA. Neuronal activity in the medial prefrontal cortex during pavlovian eyeblink and nictitating membrane conditioning. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:6296–6306. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06296.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DA, McLaughlin J, Chachich M. Classical conditioning of autonomic and somatomotor responses and their central nervous system substrates. In: Steinmetz JE, Woodruff-Pak DS, editors. Eyeblink classical conditioning. Vol. 2. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 257–286. Animal models. [Google Scholar]

- Powell DA, Watson K, Maxwell B. Involvement of subdivisions of the medial prefrontal cortex in learned cardiac adjustments. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1994;108:294–307. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Garcia R, Gonzalez-Lima F. Prefrontal mechanisms in extinction of conditioned fear. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Mueller D. Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;33:56–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robleto K, Poulos AM, Thompson RF. Brain mechanisms of extinction of the classically conditioned eyeblink response. Learning and Memory. 2004;11:517–524. doi: 10.1101/lm.80004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Woolsey CN. The orbitofrontal cortex and its connections with the mediodorsal nucleus in rabbits, sheep and cat. Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Diseases. 1948;27:210–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek JW, Wen GY, Wisniewski HM. Atlas of the rabbit brain and spinal cord. New York: Karger; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Simon BB, Knuckley B, Churchwell J, Powell DA. Post-training lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex interfere with subsequent performance of trace eyeblink conditioning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:10740–10746. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3003-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takehara K, Kawahara S, Kirino Y. Time-dependent reorganization of the brain components underlying memory retention in trace eyeblink conditioning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:9897–9905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09897.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RF. Discovering the brain substrates of eyeblink classical conditioningEyeblink classical conditioning. In: Steinmetz JE, Woodruff-Pak DS, editors. Animal models. Vol. 2. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Sikes RW, Swadlow HA, Weyand TG. Rabbit cingulate cortex: Cytoarchitecture, physiological border with visual cortex, and afferent cortical connections of visual, motor, postsubicular, and intracingulate origin. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1986;248:74–94. doi: 10.1002/cne.902480106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weible AP, McEchron MD, Disterhoft JF. Cortical involvement in acquisition and extinction of trace eyeblink conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:1058–1067. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.6.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weible AP, Weiss C, Disterhoft JF. Activity profiles of single neurons in caudal anterior cingulate cortex during trace eyeblink conditioning in the rabbit. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;90:599–612. doi: 10.1152/jn.01097.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]