Summary

The Campylobacter fetus surface layer proteins (SLPs), encoded by five to nine sapA homologues, are major virulence factors. To characterize the sapA homologues further, a 65.9 kb C. fetus genomic region encompassing the sap locus from wild-type strain 23D was completely sequenced and analysed; 44 predicted open reading frames (ORFs) were recognized. The 53.8 kb sap locus contained eight complete and one partial sapA homologues, varying from 2769 to 3879 bp, sharing conserved 553–2622 bp 5′ regions, with partial sharing of 5′ and 3′ non-coding regions. All eight sapA homologues were expressed in Escherichia coli as antigenic proteins and reattached to the surface of SLP− strain 23B, indicating their conserved function. Analysis of the sap homologues indicated three phylogenetic groups. Promoter-specific polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) and sapA homologue-specific reverse transcription (RT)-PCRs showed that the unique sapA promoter can potentially express all eight sapA homologues. Reciprocal DNA recombination based on the 5′ conserved regions can involve each of the eight sapA homologues, with frequencies from 10−1 to 10−3. Intragenic recombination between sapA7 and sapAp8, mediated by their conserved regions with a 10−1–10−2 frequency, allows the formation of new sap homologues. As divergent SLP C-termini possess multiple antigenic sites, their reciprocal recombination behind the unique sap promoter leads to continuing antigenic variation.

Introduction

Campylobacter fetus are spiral, microaerophilic, Gram-negative bacterial pathogens that cause infertility and infectious abortion in ungulates, and septicaemia, meningitis and other systemic infections in humans, especially in infants and HIV-infected persons (Guerrant et al., 1978; Garcia et al., 1983; Skirrow, 1990; Blaser, 1998; Thompson and Blaser, 2000). In common with many other bacteria (Walker et al., 1992; Sleytr et al., 1993), C. fetus expresses a paracrystalline surface layer (S-layer) on its outermost cell surface (Dubreuil et al., 1988; 1990; Fujimoto et al., 1991). The S-layer is the major C. fetus virulence factor, rendering cells resistant to serum killing by impairing C3b binding (Blaser et al., 1987; 1988; Blaser and Pei, 1993). Each S-layer is composed of high-molecular-weight S-layer proteins (SLPs), and C. fetus cells vary the SLPs expressed. The SLPs are essential for host colonization (Grogono-Thomas et al., 2000), and their antigenic variation helps to evade host immune responses (Wang et al., 1993; Garcia et al., 1995).

In culture, each C. fetus strain usually expresses one predominant SLP, although subpopulations of cells can express variant SLPs of apparent molecular weights ranging from 97 to 149 kDa (Blaser et al., 1994). The SLPs are encoded by five to nine sapA homologues tightly clustered on the chromosome (Dworkin et al., 1995a; Garcia et al., 1995; Tu et al., 2001a), and each sapA homologue is potentially expressed by the unique sapA promoter (Dworkin and Blaser, 1996). SLP phenotypic switching in C. fetus appears to involve high-frequency chromosomal DNA rearrangements that occur within the sap genomic locus, as shown in studies of three sapA homologues (Dworkin et al., 1997; Dworkin and Blaser, 1997a; Ray et al., 2000; Tu et al., 2001b).

As the genomic organization and the structural features of all the sap genes have not been described, we have now identified and characterized a 53.8 kb chromosomal region containing the entire sap locus in wild-type strain 23D. We show that all eight complete sapA homologues share conserved regions at their 5′ regions, encode SLPs from 96 kDa to 131 kDa that share similar characteristics and can be divided into three phylogenetic groups based on their 3′ sequences. Experimental evidence is presented that each sapA homologue can reciprocally recombine with the others, with rearrangements permitting the creation of new homologues and their placement downstream of the unique sapA promoter.

Results

Organization and content of the sap locus

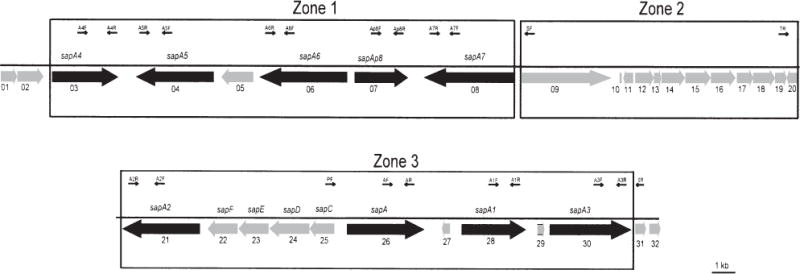

Our previous studies showed that the cloned sapA, sapA1 and sapA2 homologues share at least their 553 bp 5′ conserved regions, and their encoded SLPs are antigenically cross-reactive (Tummuru and Blaser, 1993; Wang et al., 1993; Dworkin et al., 1995a). To clone the other sapA homologues, a library of C. fetus chromosomal DNA was constructed in Escherichia coli and screened with either immune serum recognizing C. fetus SLPs (Pei et al., 1988) or a DNA probe specific for the sapA 5′ conserved region (Tu et al., 2001a). Sequence analysis of the inserts of the 16 positive clones obtained showed that they overlapped; a 65.9 kb region of the C. fetus chromosome was reconstructed containing a cluster of 44 open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary material, Fig. S1). Of these ORFs, eight were identified as complete sapA homologues, and these were designated sapA, sapA1, … and sapA7. The sequences of sapA, sapA1 and sapA2 were consistent with our previous reports (Blaser and Gotschlich, 1990; Tummuru and Blaser, 1993; Dworkin et al., 1995a). A partial sapA homologue lacking the 5′ conserved region was identified and named sapAp8. Additional ORFs present in the 65.9 kb chromosomal region were designated Cf0001, Cf0002, … and Cf0044 based on their location within the sequenced region (Fig. 1 and Supplementary material, Fig. S1 and Table S1). We defined the sap locus as the 53 845 bp sequence between Cf0002 and Cf0031, as it contains all the sapA homologues, and we divided this into three zones based on the location of the homologues (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation and genomic organization of the sap locus in C. fetus strain 23D. The adjacent ORFs that are not sapA homologues (including sapC, D, E, F and Cf0001 … Cf0032) are indicated by shaded boxes. The PCR primers used in this study (PF, SF, TR, SR, AF–A7F and AR–A7R) are designated by the arrows, which also denote the primer orientations. The horizontal line indicates the length of the fragment.

In total, the 65.9 kb chromosomal segment had a G+C content of 34.2%, although the G+C content distribution within this region was not uniform (Supplementary material, Fig. S1). Analysis of the 28 662 bp representing the nine complete or partial sapA homologues shows a G+C content of 37.1% with small differences (36.4–38.1%) between the homologues (Table 1). This is higher than for the 19 other no-sap ORFs in the sap locus (18 165 bp; 34.6%) and the 16 ORFs flanking the locus (1,1203 bp; 32.2%). The codon preferences are similar between the sapA homologues and the other ORFs within the sap locus (data not shown).

Table 1.

C. fetus sapA homologues, their products and recombinant plasmids.

| Homologue

|

Predicted protein

|

Recombinant plasmidb (size of insert, bp) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | ORF | Size (bp) | %(G+C)a | Amino acid (no.) | Mass (kDa) | Isoelectric point | |

| sapA | cf-26 | 2820 | 37.8 | 939 | 95.6 | 4.31 | pZT301 (4175) |

| sapA1 | cf-27 | 2769 | 37.5 | 922 | 95.1 | 4.36 | pZT302 (4374) |

| sapA2 | cf-21 | 3330 | 36.2 | 1109 | 111.7 | 4.22 | pZT303 (3567) |

| sapA3 | cf-29 | 3504 | 38.1 | 1167 | 117.2 | 4.28 | pZT304 (11171) |

| sapA4 | cf-03 | 2829 | 36.9 | 942 | 96.6 | 4.35 | pZT305 (5452) |

| sapA5 | cf-04 | 3321 | 37.1 | 1106 | 111.5 | 4.21 | pZT306 (7499) |

| sapA6 | cf-06 | 3774 | 36.8 | 1257 | 129.2 | 4.50 | pZT307 (7864) |

| sapA7 | cf-08 | 3879 | 37.2 | 1292 | 130.7 | 4.27 | pZT308 (10502) |

| sapAp8 | cf-07 | 2295 | 36.1 | 794 | 88.2 | 5.67 | pZT309 (6410) |

G+C content for entire C. fetus genome is 32–35% (Sebald and Veron, 1963)

The fragment that contained each ORF was cloned into E. coli in pBluescript SK+ and induced with IPTG to express the putative sapA homologue.

Structural features and comparison of the sapA homologues and their deduced proteins

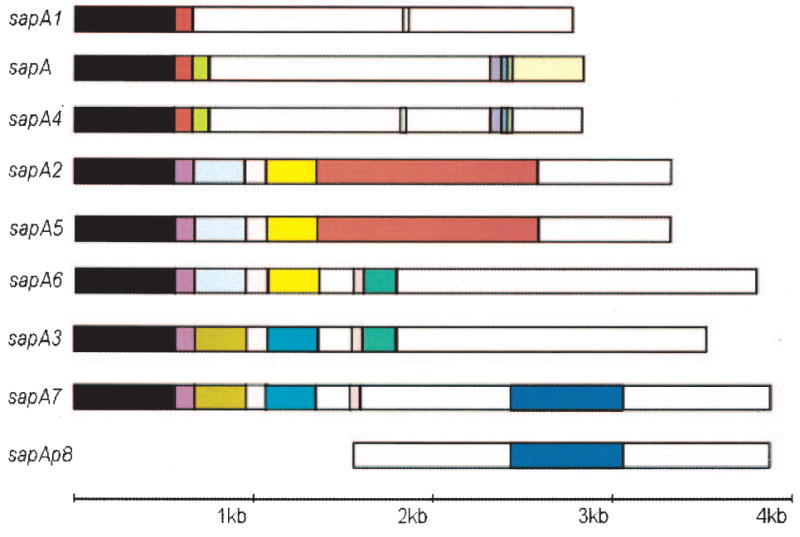

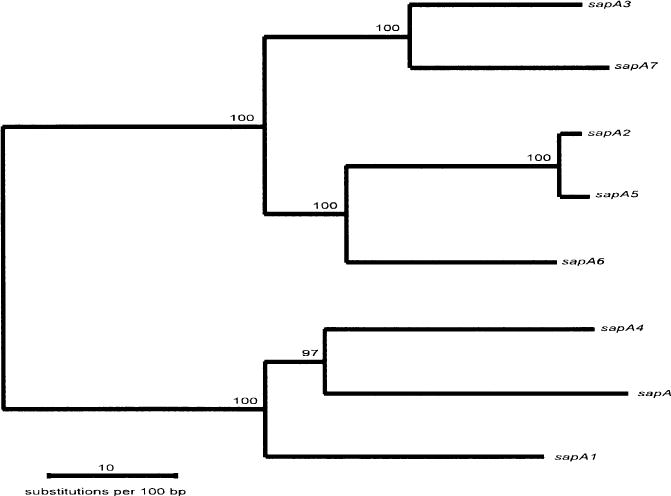

The deduced proteins encoded by the eight complete sapA homologues ranged from 922 to 1257 amino acids, with calculated molecular weights of 95.1 kDa to 129.2 kDa, and each of the predicted SLPs had a similar isoelectric point (4.21–4.50) (Table 1). Alignment of the eight complete sapA homologues revealed several striking aspects of sap structural similarity, sequence divergence and variability. Each homologue shared at least a 553 bp 5′ conserved region (FCR), although the identity was considerably greater for some pairs of sapA homo-logues (Fig. 2). A 656 bp FCR exists among sapA, sapA1 and sapA4, a 662 bp FCR among sapA2, sapA3, sapA5, sapA6 and sapA7, a 1349 bp FCR between sapA3 and sapA7, a 1364 bp FCR among sapA2, sapA5 and sapA6, and a 2622 bp FCR between sapA2 and sapA5 (Fig. 2). Several other identical segments >50 bp were found between sapA and sapA4, sapA1 and sapA4, and among sapA3, sapA6 and sapA7 (Fig. 2). A multiple sequence alignment of all eight sapA homologues at the amino acid level was created using the GCG program (Wisconsin Package version 9.1) (Supplementary material, Fig. S2). The phylogeny of the eight complete sapA homologues showed that they formed three tight clusters; the high bootstrap values indicate that the clusters are robust (Fig. 3). The first cluster, designated group AZ, consists of sapA, sapA1 and sapA4, encoding lower molecular mass SLPs (95.1, 95.6, and 96.6 kDa SLPs respectively). The second cluster (AY) consists of sapA2, sapA5 and sapA6, which encode SLPs of different molecular mass (111.7, 111.5 and 129.2 kDa respectively), and the third cluster (AX) consists of sapA3 and sapA7. Representatives of each of the three groupings are present in zones 1 and 3 of the sap locus (Figs 1 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Structural features and comparison of DNA sequences of eight complete and one partial sapA homologue. The structure of each homologue is represented schematically by the aligned rectangles. Coloured boxes identify shared regions of identity among the homologues. White boxes indicate non-conserved sequences, with no sequences> 30 bp shared. The first 553 bp in all eight complete sapA homologues are shared. The Cf0007 ORF shares 752 bp with sapA7, but lacks the 5′ conserved region; it is referred to as sapAp8, as it is a partial homologue.

Fig. 3.

Phylogeny of the eight complete sapA homologues in C. fetus strain 23D. The phylogeny was constructed from the nucleotide sequences of the eight sapA homologues, using the neighbour-joining method, based on Kimura’s two-parameter model distance matrices. Bootstrap values (% based on 500 replicates) are represented at each node, and the branch length index is shown below the tree.

Analysis of the putative secondary structures of the SLPs encoded by the eight sapA homologues showed that the C-terminal 200 amino acids possess rich antigenic sites (Jameson and Wolf, 1998 Supplementary material, Fig. S3). This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that the C-termini encoded by the 3′ divergent regions of the sap homologues form the basis for antigenic variation of their SLPs (Dworkin et al., 1995b); the SLP secretion signal is located within the C-terminal 100 amino acids (unpublished data).

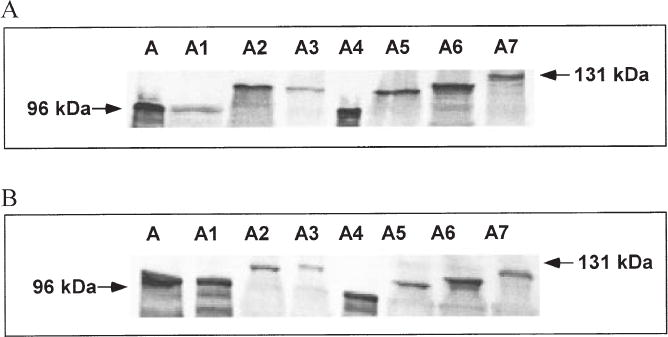

Function of the sapA homologue-encoded products

To determine whether each of the ORFs is capable of encoding a functional SLP, the recombinant sapA homologues were cloned into E. coli in pGEM-T Easy Vector, an expression vector. All eight complete sapA homologues could be expressed in E. coli using the induced vector-encoded promoter, and their products were all recognized by polyclonal rabbit serum against the 97 kDa SLP from C. fetus strain 82-40LP (Fig. 4A). Thus, when downstream of an active E. coli promoter, each of these putative genes is capable of encoding an antigenic full-length SLP. Another function of the C. fetus SLPs is their ability to attach to the surface of C. fetus cells via a type-specific linkage with the lipopolysaccharide O side-chains (Yang et al., 1992). Each of the cloned products was able to attach to SLP-negative type A strain 23B (Fig. 4B), but not to SLP-negative type B strain 83–88 (data not shown). These results, indicating that each of the homologues can encode an SLP with the appropriate LPS-binding specificity, provide evidence that they are fully functional when expressed using an active promoter.

Fig. 4.

Immunoblot of the SLPs encoded by the sapA homologues and their attachment to cells of type A SLP− C. fetus strain 23B.

A. The SLPs were assayed using sonicates prepared from E. coli cells transformed with recombinant plasmids (pZT301 to pZT308) with inserted fragments k, m, h, o, a, c, d and f (see Table 1 and Supplementary material, Fig. S1), which express the products of sapA, sapA1, sapA2, sapA3, sapA4, sapA5, sapA6 and sapA7 respectively. The sonicates were electrophoresed on a 7% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, the bands were electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, then probed with polyclonal rabbit serum against the 97 kDa SLP of C. fetus strain 82–40 LP. The arrows indicate the major immunoreactive protein bands.

B. Lysates of E. coli cells expressing the SLPs were incubated with SLP− 23B cells and then washed repeatedly with C-buffer, as described previously (Yang et al., 1992). The 23B cell pellets were then electrophoresed, and immunoblotting was performed as described above.

Characterization of the sequences flanking the sap homologues

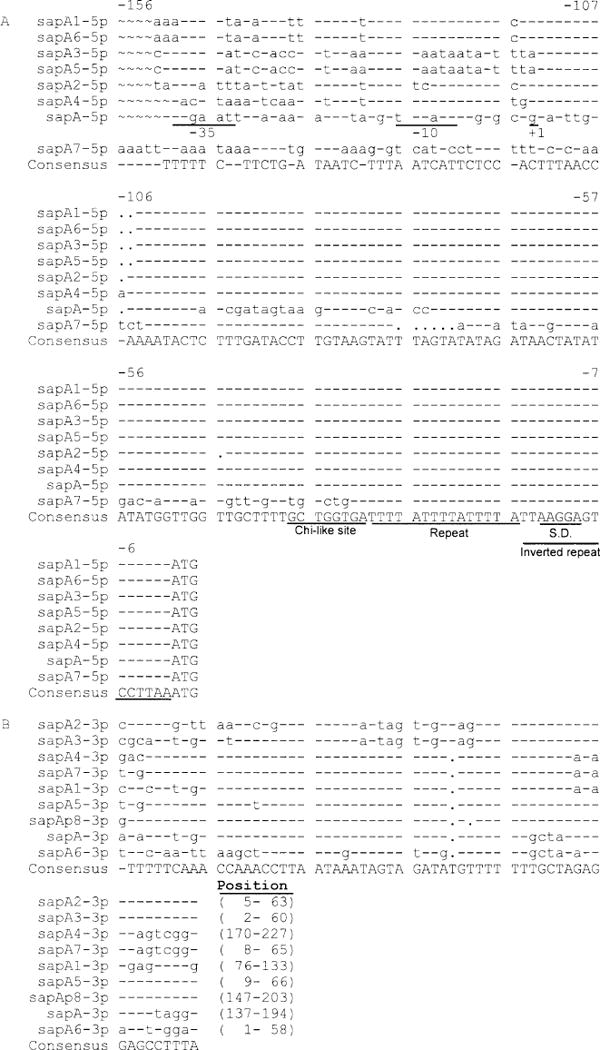

Alignment of the regions upstream of the eight complete sapA ORFs showed that all shared about 103 bp identity, with small exceptions involving sapA5 and sapA7 (Fig. 5A). The 199 bp immediately upstream of sapA1 (group AZ) and sapA6 (group AY) are identical, as are the 163 bp immediately upstream of sapA3 (group AX) and sapA5 (group AY). In each case, the paired upstream regions are present in zones 1 and 3. All eight complete sapA homologues are preceded by a putative Shine–Dalgarno sequence (AGGAG) (−12 to −8), a 17 bp inverted repeat ending at the ATG initiation codon, an octomer (GCTGGTGA) that shares seven of 8 bp with the E. coli Chi-site, followed by three pentameric (TTTTA) repeats (Fig. 5A). The previously characterized sap promoter (Tummuru and Blaser, 1992; Dworkin and Blaser, 1997b) is present upstream of only a single homologue (sapA); no putative promoter structures were identified upstream of any of the other homologues. Alignment of the 3′ regions downstream of the eight complete and one partial sapA homologues showed a conserved region of about 50 bp at varying distances (commencing 1–170 bp) after the stop codon for sapA2, sapA3 and sapA5 (Fig. 5B). In total, these data indicate highly conserved sequences upstream of each homologue, as well as partially conserved sequences both upstream and downstream of particular homologues.

Fig. 5.

Alignment of sequences upstream (A) and downstream (B) of the eight complete sapA ORFs. Putative promoter elements (−35 and −10 sequences) and the transcription start site (+1) for sapA are indicated (Tummuru and Blaser, 1992). Putative Shine–Dalgarno (SD; −13 to −9) and Chi-like sequences (−38 to −31) upstream of the ATG start codon ATG, as well as a pentameric repeat (TTTTA; −31 to −17) and the 17 bp inverted repeat (−1 to −17), are indicated. Although sapA1 and sapA6 each have closer homologues (Figs 2 and 3), the 150 bp upstream of each are identical. A parallel phenomenon exists for sapA3 and sapA5. All eight complete sapA homologues share partially conserved sequences in a 60 bp region differentially located downstream of their ORFs.

Characteristics of other ORFs within the sap locus

The regions between the sapA homologues varied from 744 bp (sapA4–sapA5) to 12.42 kb (sapA7–sapA2), often containing additional ORFs (Fig. 1, Supplementary material, Fig. S1 and Table S1). The region between sapA and sapA2 contains the unique sap promoter and the genes necessary for SLP secretion, as described previously (Thompson et al., 1998). The 1389 bp Cf0005 ORF located between sapA5 and sapA6 showed a 462-amino-acid hypothetical protein. The ORF Cf0027 between sapA and sapA1 encoded a 206-amino-acid conserved protein of unknown function. The predicted product of ORF Cf0029 between sapA1 and sapA3 showed 41% identity with Helicobacter pylori hypothetical protein Hp0892 (E ( ): 1e-12). The 12.4 kb between sapA7 and sapA2 contains 12 predicted ORFs. ORF Cf0009 is predicted to encode a protein highly homologous (E ( ): 3e-13) to Hmw2A, which is an adhesin in Haemophilus influenzae (Barenkamp and Leininger, 1992). The products of ORFs Cf0010, Cf0011, Cf0014 and Cf0015 were homologous to Cj1360, Cj1361, Cj1362 and Cj1363 (100%, 25%, 72% and 48% amino acid identities respectively). Cf-14 encodes a homologue (E ( ): e-132) to Campylobacter jejuni RuvB (Parkhill et al., 2000), which is a Holliday junction DNA helicase in E. coli, involved in resolution of DNA recombination products. The predicted products of ORFs Cf0016, Cf0017 and Cf0018 constitute a potential ABC transport system homologous to Cj1646, Cj1647 and Cj1648, with identities of 46%, 52% and 26% respectively. The Cf0020 product shares 59% identity with Cj0121, the function of which is unknown, and the Cf0013 and Cf0019 predicted products have no significant homologies in GenBank.

Sequence analysis of DNA segments flanking the sap locus

Upstream of the sap locus were two ORFs with sequences indicating apparently related functions. The Cf0002 ORF immediately upstream of sapA4 encodes a predicted protein with substantial (28% identity) similarity to the E. coli MtfB protein (E ( ): 3e-44) (Table 1). In E. coli, MtfB is a mannosyltransferase involved in lipopolysaccharide assembly (Kido et al., 1995). The incompletely sequenced Cf0001 ORF predicts a protein with 33% identity to Archaeoglobus fulgidus MtfA (mannosyltransferase A) (E ( ): 6e-25). As C. fetus SLPs bind specifically (Fogg et al., 1990; Yang et al., 1992; Dworkin et al., 1995b) to the mannose-rich (Moran et al., 1994) type A LPS, these ORFs may have LPS-related functions specific for type A strains. Downstream of sapA3, the 9.9 kb sequence obtained contains 14 ORFs, the first five of which (Cf0031–Cf0035) are oriented in the same direction and appear to constitute a single operon (Supplementary material, Fig. S1 and Table S1). The remaining nine ORFs (Cf0036–Cf0044) are in the opposite orientation. These genes predict proteins with a variety of functions, including a putative two-component regulatory system (Cf0030 and Cf0031) (Supplementary material, Fig. S1 and Table S1). For none of these ORFs is there a putative function that can currently be related directly to SLP production or function.

Potential expression of the sapA homologues

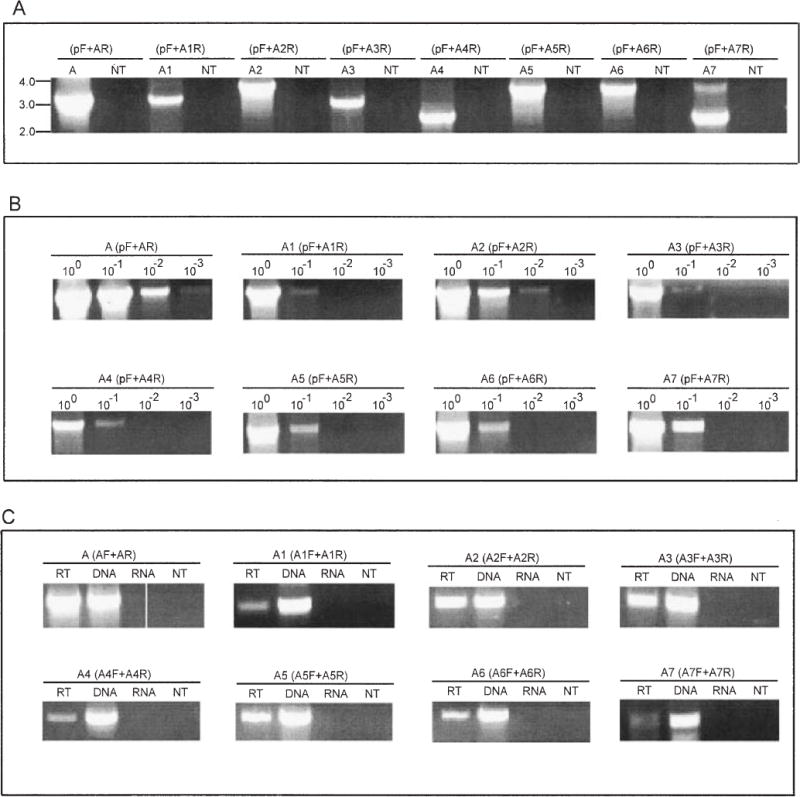

Our previous studies showed that there is a single sap promoter that could express sapA, sapA1 or sapA2, depending on which homologue was located immediately downstream (Dworkin and Blaser, 1996; 1997a), and we now show that it is unique within the sap locus (Fig. 5A). To address the hypothesis that C. fetus can use this unique sap promoter to express each of the eight complete sapA homologues, we performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with strain 23D DNA as template using a (forward) promoter-specific primer with (reverse) primers specific for each sapA homologue. From these PCRs, all eight sap homologue-specific products were obtained (Fig. 6A), indicating that, through DNA rearrangements (Dworkin and Blaser, 1997a; Tu et al., 2001b), each of the homologues can be expressed by the unique sap promoter. We next sought to estimate the frequencies at which the other sapA homologues could rearrange behind the promoter, in comparison with sapA. PCRs were performed with 100–10−3 dilutions of the 23D template DNA, using a promoter-specific primer paired with sapA homologue-specific primers, representing zone 1 and zone 3 sapA homologues at different distances from the sapA promoter. Although products were observed in each PCR with undiluted templates, the sapA primer yielded products at the highest dilutions, compared with the other primers (Fig. 6B), indicating that, in this strain, it is in the preferred position for expression. To investigate further the hypothesis that a population of C. fetus cells includes variants with differing SLP expression, we performed reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using sapA homologue-specific primers; the results indicate that mRNAs for each of the eight sapA homologues can be detected in a population of cells of strain 23D (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

PCR and RT-PCR assessment of recombination involving the sapA homologues with their placement and expression downstream of the unique sapA promoter.

A. PCR amplifications used the (forward) unique sap promoter-specific primer (pF) with (reverse) sap homologue-specific primers (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary material). A, A1, …, A7 represent products representative of sapA, sapA1, …, sapA7, respectively, and NT represents the no DNA template negative control. Results indicate that the C. fetus 23D population includes cells in which each of the specified recombinations has occurred

B. Semi-quantitative PCR of the recombination involving sapA (control) and the other seven sapA homologues. In each case, the homologue-specific primer was used with the promoter-specific primer, and serial 10-fold dilutions of the 23D template chromosomal DNA are represented.

C. RT-PCR to detect mRNA specific to each of the eight sapA homologues in strain 23D. Each PCR was performed using paired sap homologue-specific primers (Fig. 1). PCR using the DNA template was a positive control, and PCRs using the RNA or no template (NT) were used as negative controls.

DNA rearrangements in the sap locus

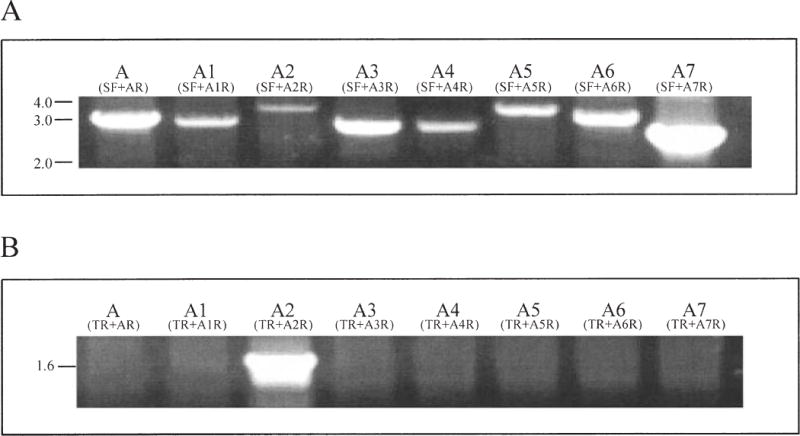

The sapA homologues are present in inverted orientations to one another in zone 1, with the outermost homologues facing inwards, and in zone 3 with them facing outwards. In either case, the presence of inverted repeated DNA permits reciprocal recombination, as described previously (Tummuru and Blaser, 1993; Dworkin and Blaser, 1997a). Next, we hypothesized that the sap homologue FCR sequences present in both orientations may mediate DNA rearrangements that can involve any homologue. To address whether DNA recombination involves the sapA homologues directly, we performed a further series of illustrative PCRs, using a primer (SF) immediately upstream of the sapA7 ORF, paired with reverse primers specific for each sapA homologue. That specific bands of the expected sizes were obtained for all eight complete sapA homologues (Fig. 7A) indicates that DNA recombination can occur between sapA7 and each of the other sapA homologues, regardless of their proximity to sapA7.

Fig. 7.

PCR assessment of sapA homologue intragenic recombination.

A. DNA rearrangement involving sapA7 and the seven other complete sap homologues. PCRs used the sapA7 5′ non-coding region forward primer (SF) with the eight sapA homologue-specific reverse primers (primers AR to A7R) (Fig. 1A; Supplementary material, Table S2).

B. PCRs using the sapA2 3′ non-coding region reverse primer (TR) with sapA homologue-specific forward primers (primers AF to A7F) (Fig. 1).

To test the hypothesis that homologous regions downstream of the sap homologues also play a role in recombination, PCRs were performed using a reverse primer (TR) located in the non-coding region downstream of the sapA2 ORF, paired with forward primers specific for each of the eight complete sapA homologues. In these PCRs, only the control sapA2-specific product was amplified (Fig. 7B). A parallel PCR that used the sapA3-specific downstream (non-coding) region primer (SR) with primers for the eight complete homologues showed parallel results (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that recombination can involve any pair of sapA homologues, and is mediated by their 5′ but not by their 3′ conserved regions. Variation in the cross-over points for these recombination events (Tu et al., 2001a) can result in a large number of potential variants.

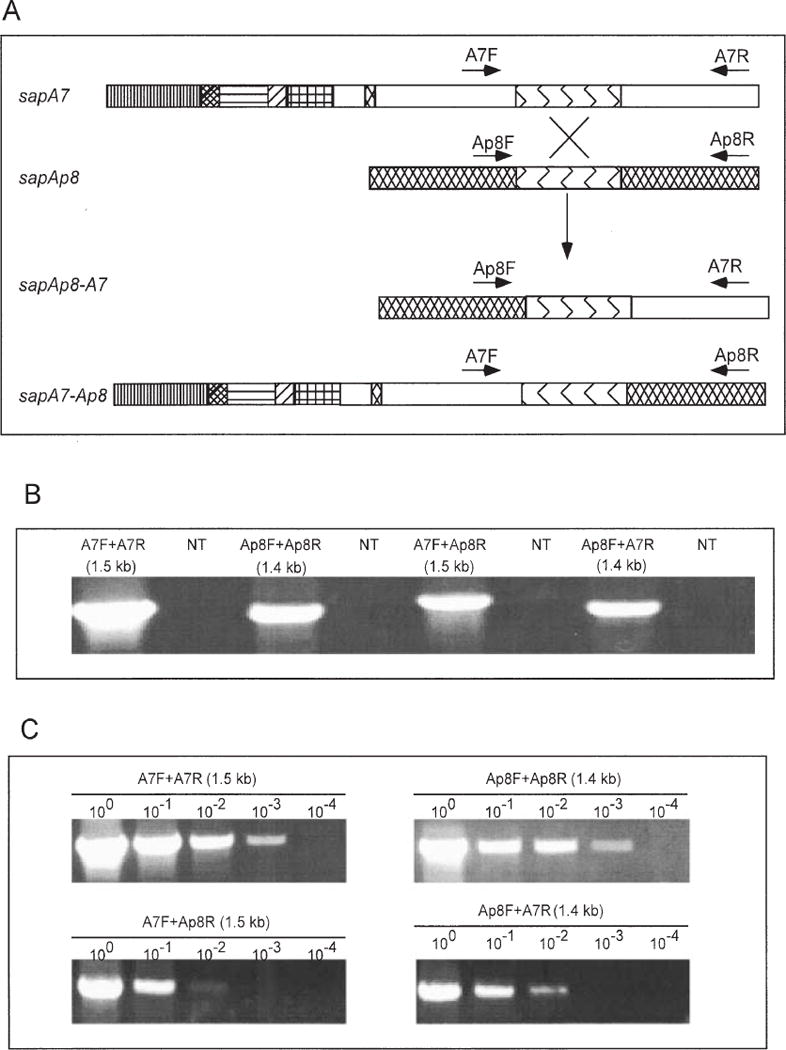

Intragenic DNA recombination between sapA7 and sapAp8 homologues

To investigate further the functional biology of the sap locus, we hypothesized that intragenic DNA recombination might create new sap homologues (Fig. 8A). We studied recombination between sapA7 and sapAp8, as conserved 752 bp sequences exist within their middle regions (Fig. 2). Control PCRs with primers flanking the conserved regions of sapA7 and sapAp8 yielded the expected 1.5 and 1.4 kb products respectively (Fig. 8B). PCRs that paired the sapA7 primers with sapAp8 primers also yielded products of sizes consistent with recombination (Fig. 8B), and sequence analysis proved that the expected recombination had occurred (data not shown). Thus, DNA recombination between sapA7 and sapAp8, mediated by their middle conserved regions, can produce two new chimeric sap homologues, sapA7-Ap8 and sapAp8-A7. The frequency of chimera formation was estimated as ≈ 10−1–10−2 by template DNA dilution PCR (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

PCR detection of sapA7–sapAp8 chimera formation.

A. Schematic of sapA7 and sapAp8 homologues and postulated chimeras sapAp8-A7 and sapA7-Ap8 produced by intragenic recombination mediated by the conserved region (Fig. 2). The hatched area indicates the sapAp8-specific regions, blue represents the 752 bp conserved region, and white represents the sapA7-specific regions. The different hatched regions of sapA7 are consistent with the coloured regions in Fig. 2.

B. The PCR products amplified using sapA7- and sapAp8-specific primers (Fig. 1). With either 23D DNA or no template, the results indicate the occurrence of intragenic DNA recombination, producing sap chimeras between sapA7 and sapAp8.

C. Template dilution PCR for determining the frequency of sapA7–sapAp8 chimera formation.

Discussion

Previous Southern hybridization and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) studies showed that there are eight sapA homologues in a chromosomal region of <93 kb for wild-type C. fetus strain 23D (Tummuru and Blaser, 1992; Dworkin et al., 1995b). Similarly, for strain 82–40, all the homologues were located in a region no larger than 135 kb (Dworkin et al., 1995b) and, for other C. fetus strains, up to nine homologues may be present (Fujita and Amako, 1994; Fujita et al., 1995; Tu et al., 2001a). Comparisons of the cloned sapA, sapA1 and sapA2 homologues demonstrated that they shared at least a 553 bp sequence in their FCR (Tummuru and Blaser, 1993; Dworkin et al., 1995b), which differed from the parallel regions of sapB homologues found in C. fetus serotype B strains (Dworkin et al., 1995a; Casademont et al., 1998). In this study, by identifying all eight complete sapA homologues in strain 23D, we found that all share 5′ identity, but the extent of identity ranges from 553 to 2750 bp (Fig. 2). Phylogenetic analysis of these homologues shows that they can be divided into three significantly different groups (designated AX, AY or AZ; Fig. 3), suggesting that each of the groups may have a specialized function. One model for their evolution is that the homologues arose from a progenitor by a series of gene duplications with selection for particular genes that conferred specific functions (Bzymek and Lovett, 2001).

The conserved regions of the eight sapA homologues represent tandem repeats, which through recombination may mediate DNA inversion, deletion or duplication in an individual C. fetus cell or allow the formation of new sapA homologues. For example, in its middle region, sapA6 shares 333 bp with its AY family members sapA2 and sapA5, as well as a 454 bp region with sapA3 (group AX, Fig. 3). One possibility for the formation of sapA6 is through recombination between progenitor sapA5 and sapA3 homologues. Similarly, the extensive homologies provide substantial opportunities for reciprocal recombination events producing varied homologues; our experimental results (Fig. 8) confirm the presence of such recombinants. The putative (Supplementary material, Fig. S3) and actual (Wang et al., 1993) antigens observed in the homologues could then vary further, based on reciprocal recombination between particular homologues. Such recombination would create antigenic variation far in excess of that encoded by the eight or nine homologues, and can explain the ability of C. fetus to persist in immunocompetent hosts for years (Thompson and Blaser, 2000).

Between sapA6 and sapA7 is a 2295 bp ORF (sapAp8) that shares a 752 bp conserved region with sapA7 (Fig. 2). This ORF appears to be a pseudogene, which we show (Fig. 8) can recombine with sapA7 to increase diversity further. We speculate that sapA7, at the 3′ boundary of zone 1 in strain 23D, being inverted in relation to five other homologues in both zones, and adjacent to and able to recombine with its partially homologous pseudogene, may be a critical homologue for the entire recombination process.

That tandem direct repeats can mediate either DNA duplication or deletion has been reported in other bacterial species (Dybvig, 1983; Bi and Liu, 1996; Leblond et al., 1996; Bzymek and Lovett, 2001; Clement et al., 2001). In strain 23B, an in vitro-passaged mutant of wild-type strain 23D, the sap promoter was deleted (Tummuru and Blaser, 1992), an event possibly mediated by recombination between the conserved directly repeated regions of sap homologues; experimental evidence supports this hypothesis (Fujita et al., 1995). Although there is strong selection for SLP expression in vivo (Dworkin et al., 1995b), and thus retention of the unique sap promoter, selection in vitro might favour loss of SLP expression, as SLP− strains can devote more resources to other cellular functions, and there is no host selection for SLP+ in vitro.

Our previous studies have shown that, among 103 in vitro-passaged 23D colonies derived from a strain expressing sapA (97 kDa SLP), one colony expressed a 127 kDa SLP (Tu et al., 2001a). When recA strain 97–211 (expressing a 97 kDa SLP) was used to challenge a pregnant ewe, of 16 isolates, one (97–209) expressed a 127 kDa SLP; Southern hybridization demonstrated that chromosomal rearrangement enabled the SLP switch (Ray et al., 2000). In total, these in vivo and in vitro data indicate high-frequency SLP phenotypic variation. Both the sap promoter-specific PCRs and the sap homologue-specific RT-PCR provide evidence indicating that all eight sap homologues in 23D can be expressed. That products of all eight sap homologues can be expressed in E. coli and can be attached to the surface of their homologous type A cells indicates proper protein folding to conform to the structural requirements of the cation-dependent interaction with LPS (Yang et al., 1992). These studies at the DNA, mRNA and protein levels are all consistent and indicate how C. fetus uses promoter rearrangement to facilitate antigenic variation and escape from host immune defences.

In many bacterial pathogens, the genes responsible for virulence traits have been found on relatively large segments (ranging from 10 to 200 kb) of the bacterial chromosome, termed pathogenicity islands (PAIs) (Hacker et al., 1997). PAIs are identified in part by G+C content that is atypical for the organism in which they reside. Analysis of %G+C shows that the sapA homologues are significantly deviated from the mean observed in other parts of the sap locus ORFs (34.8%), the flanking ORFs (32.2%) and the expectation for the entire genome (32–35%; Sebald and Veron, 1963). These observations are consistent with the possibility that the sap locus entered the C. fetus genome horizontally, but that there has been greater amelioration of the other ORFs than of the sapA homologues. Alternatively, as suggested above, a single sapA homologue entered the genome, and subsequent gene duplications resulted in the current complement of homologues. The necessity for nucleotide fidelity for recombination efficiency may have selected for substitutions in a pattern of concerted evolution between the homologues, analogous to observations in the H. pylori bab paralogues (Pride and Blaser, 2002). In a previous 18-strain sequence comparison of portions of sapD (Cf0024, zone 3) and the housekeeping gene recA, analysis of G+C content, substitution rates and phylogeny suggests that the sap locus has been part of the C. fetus genome since before the divergence of mammals and reptiles (>200 million years) (Tu et al., 2001a). We have done extensive studies to attempt to transform C. fetus naturally, but have never been able to accomplish this (unpublished data). That C. fetus cells are not naturally competent suggests that the sap locus is not easily acquired by horizontal gene transformation, which is also consistent with its being an ancient genomic constituent (Tu et al., 2001a). In analyses to compare the similarities between the C. fetus sap island and C. jejuni strain 11168, for which the entire genome was solved (Parkhill et al., 2000), the sap island was found to be unique to C. fetus. However, of 19 non-sap ORFs within the sap locus, nine are strong homologues of C. jejuni genes (data not shown). This result further suggests that an ancestor of the sap island was introduced into an ancient, conserved Campylobacter locus, with continuing, specific selection since.

The DNA rearrangements among the sap homologues are largely but not completely RecA dependent (Dworkin et al., 1997; Ray et al., 2000), and recombination frequency is related to conserved region length (Tu et al., 2001b). Thus, the differing length of FCRs among the eight sapA homologues that we identified may mediate DNA recombination with different frequencies. Our studies showed that all eight sapA homologues can be shuttled behind the unique sap promoter by DNA rearrangement, and that reciprocal recombination can create new sapA homologues within the sap locus, regardless of their exact placement or expression. This genomic plasticity, based on recombination of homologous units, can result in substantial antigenic variation, beyond that produced by eight independent genes, leading to a repertoire of great complexity.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Campylobacter fetus strain 23D and its culture conditions have been described previously (McCoy et al., 1975; Tu et al., 2001a). E. coli strain DH5α was grown in Luria–Bertani broth (L broth) or on L plates. Ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) was added for cultivation of bacteria harbouring plasmids.

Construction and screening of C. fetus genomic library

Chromosomal DNA of C. fetus 23D was prepared using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) and partially digested by Sau3AI. Fragments >4 kb were ligated with BamHI-digested, alkaline phosphatase-treated pBluescript KS_ (Stratagene). The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli strain DH5α. The resulting C. fetus DNA library was screened for SLP expression using antiserum against the 97 kDa SLPs of type A strain 82-40LP (Pei et al., 1988; Wang et al., 1993), as described previously (Dworkin and Blaser, 1996). The library was also screened by dot hybridization using a probe specific for the 5′ conserved region of sapA homologues, which was generated by PCR from 23D using primers ACF and ACR. The probe was labelled using the Renaissance chemiluminescent non-radioactive kit (NEN Research Products).

PCR and RT-PCR analyses

To detect the potential expression of each sapA homologue by the unique sapA promoter, we performed PCR using a sapA promoter-specific forward primer (PF) with the sap homologue-specific reverse primers (AF to A7R; Fig. 1). Differences in the potential expression of sapA homologues were estimated by 10-fold serial dilutions of chromosomal DNA PCR using primer PF with sapA homologue-specific reverse primer respectively. To determine further whether DNA inversion can occur among the sapA homologues, we performed PCR using forward primer SF (located in the sapA7 5′ non-coding region) with sapA homologue-specific reverse primers (AR to A7R; Fig. 1), and another series of PCRs using reverse primer TR (located in the sapA2 3′ non-coding region) with sapA homologue-specific forward primers (AF to A7F; Fig. 1). To detect intragenic recombination between sapA7 and sapAp8, sapA7- and sapAp8-specific primers were used (Fig. 8; Supplementary material, Table S2). All the template DNA used in the PCR was isolated from a single culture of cells. Total cellular RNA was purified using the Micro to Midi total RNA purification system (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed with RETROscrip™ (Ambion), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To detect mRNAs encoding potential sap products, the RT-PCRs were performed with primers specific for each of the sapA homologues (Fig. 1). Both the original PCRs and the PCRs after reverse transcription were performed with a reaction volume of 50 μl containing 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Qiagen), 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 200 ng of each primer. The PCR protocol (30–40 cycles) included a denaturing step at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 5°C below the predicted melting temperature of the primers for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min kb−1 amplification product.

DNA sequencing and analysis

DNA sequence analysis of both strands was performed using an ABI prime cycle sequencing kit (BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS; Perkin-Elmer), with an ABI 377 DNA sequencer at the New York University School of Medicine Core Sequencing Facility. Sequences were compiled with SEQUENCHER software (Gene Codes). BLAST searches of GenBank for nucleotide and amino acid sequence homology were carried out at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Altschul et al., 1997). ORFs were detected with the NCBI ORF FINDER (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). DNA sequences were analysed using the GCG Wisconsin package, version 9.1 software. Phylograms based on sap nucleotide sequences were generated using both parsimony and distance matrix methods, using PAUP 4.0b2, and the phylograms were displayed using TREEVIEW and PAUP 3.1 (Illinois Natural Survey). The nucleotide sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in GenBank under accession number AY211269.

Immunoblot assays

Recombinant SLP proteins were detected by immunoblots on 7% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, using polyclonal rabbit serum against C. fetus strain 82-40 LP 97 kDa SLP, as described previously (Pei et al., 1988). The secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit IgG alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals).

In vitro reattachment of recombinant SLPs to the C. fetus cell surface

Recombinant C. fetus protein products recovered from sonicated E. coli cultures were suspended in C buffer (1 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and 20 mM CaCl2) and centrifuged at 13 000 r.p.m. to remove cellular membranes. C. fetus SLP− strains, 23B (serotype A) and 83–88 (serotype B) were used as templates for reattachment of recombinant proteins. Approximately 10 μg of lysate from recombinant E. coli strains was mixed with 100 μg of C. fetus cells in 30 μl of C buffer, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, cells were washed free of unbound recombinant SLP by washing and pelleting successively several times in 1 ml of C buffer. Reattachment was then assessed by immunoblot analysis with anti-97 kDa protein after SDS-PAGE, as described previously (Yang et al., 1992).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by R01 AI24145 and R29 AI43548 from the National Institutes of Health, and by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

The following material is available from http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/products/journals/suppmat/mole/mole3463/mmi3463sm.htm

Fig. S1. Schematic representation, restriction map, genomic organization and %G+C content of the sap homologues and adjacent genes in C. fetus strain 23D.

Fig. S2. Multiple amino acid sequence alignments based on the eight sapA homologues of 23D, using the GCG program (Wisconsin package, version 9.1).

Fig. S3. Plot structure of the C-terminal 200 amino acids of the deduced S-layer protein products, with Chou–Fasman analysis of the secondary structures.

Table S1. ORFs identified flanking sapA homologues in C. fetus strain 23D.

Table S2. Oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenkamp SJ, Leininger E. Cloning, expression, and DNA sequence analysis of genes encoding non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae high-molecular-weight surface-exposed proteins related to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1302–1313. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1302-1313.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi X, Liu LF. DNA rearrangement mediated by inverted repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:819–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ. Campylobacter fetus: emerging infection and model system for bacterial pathogenesis at mucosal surfaces. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:256–258. doi: 10.1086/514655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, Gotschlich EC. Surface array protein of Campylobacter fetus: cloning and gene structure. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14529–14535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, Pei Z. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections: critical role of high molecular-weight S-layer proteins in virulence. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:372–377. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, Smith PF, Hopkins JA, Heinzer I, Bryner JH, Wang WL. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections: serum resistance associated with high-molecular-weight surface proteins. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:696–706. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, Smith PF, Repine JE, Joiner KA. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections. Failure of encapsulated Campylobacter fetus to bind C3b explains serum and phagocytosis resistance. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:1434–1444. doi: 10.1172/JCI113474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, Wang E, Tummuru MK, Washburn R, Fujimoto S, Labigne A. High-frequency S-layer protein variation in Campylobacter fetus revealed by sapA mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:453–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzymek M, Lovett ST. Instability of repetitive DNA sequences: the role of repetitive DNA sequences: the role of replication in multiple mechanisms. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8319–8325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111008398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casademont I, Chevrier D, Guesdon JL. Cloning of a sapB homologue (sapB2) encoding a putative 112-kDa Campylobacter fetus S-layer protein and its use for identification and molecular genotyping. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21:269–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement P, Pieper DH, Gonzalez B. Molecular characterization of a deletion/duplication rearrangement in tfd genes from Ralstonia eutropha JMP134 (pJP4) that improves growth on 3-chlorobenzoic acid but abolishes growth on 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Microbiology. 2001;147:2142–2148. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil JD, Logan SM, Cubbage S, Eidhin DN, McCubbin WD, Kay CM, et al. Structural and biochemical analyses of a surface array protein of Campylobacter fetus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4165–4173. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4165-4173.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil JD, Kostrzynska M, Austin JW, Trust TJ. Antigenic differences among Campylobacter fetus S-layer proteins. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5035–5043. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5035-5043.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J, Blaser MJ. Generation of Campylobacter fetus S-layer protein diversity utilizes a single promoter on an invertible DNA segment. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1241–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J, Blaser MJ. Nested DNA inversion as a paradigm of programmed gene rearrangement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997a;94:985–990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J, Blaser MJ. Molecular mechanisms of Campylobacter fetus surface layer protein expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997b;26:433–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6151958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J, Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ. Segmental conservation of sapA sequences in type B Campylobacter fetus. J Biol Chem. 1995a;270:15093–15101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J, Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ. A lipopolysaccharide-binding domain of the Campylobacter fetus S-layer protein resides within the conserved N terminus of a family of silent and divergent homologs. J Bacteriol. 1995b;177:1734–1741. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1734-1741.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J, Shedd OL, Blaser MJ. Nested DNA inversion of Campylobacter fetus S-layer genes is recA dependent. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7523–7529. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7523-7529.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybvig K. DNA rearrangements and phenotypic switching in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:465–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg GC, Yang L, Wang E, Blaser MJ. Surface array proteins of Campylobacter fetus block lectin-mediated binding to type A lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2738–2744. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2738-2744.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto S, Takade A, Amako K, Blaser MJ. Correlation between size of the surface array protein and morphology and antigenicity of the Campylobacter fetus S layer. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2017–2022. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2017-2022.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Amako K. Localization of the sapA gene on a physical map of Campylobacter fetus chromosomal DNA. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:375–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00282100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Morooka T, Fujimoto S, Moriya T, Amako K. Southern blotting analyses of strains of Campylobacter fetus using the conserved region of sapA. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164:444–447. doi: 10.1007/BF02529743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MM, Eaglesome MD, Rigby C. Campylobacters important in veterinary medicine. Vet Bull. 1983;53:793–818. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MM, Lutze-Wallace CL, Denes AS, Eaglesome MD, Holst F, Blaser MJ. Protein shift and antigenic variation in the S-layer of Campylobacter fetus subsp. venerealis during bovine infection accompanied by genomic rearrangement of sapA homologs. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1976–1980. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.1976-1980.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogono-Thomas R, Dworkin J, Blaser MJ, Newell DG. Roles of the surface layer proteins of Campylobacter fetus subsp. fetus in ovine abortion. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1687–1691. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1687-1691.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrant RL, Lahita RG, Winn WC, Roberts RB. Campylobacteriosis in man: pathogenic mechanisms and review of 91 bloodstream infections. Am J Med. 1978;65:584–592. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90845-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Muhldorfer I, Tschape H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson BA, Wolf H. the antigenic index: a novel algorithm for predicting antigenic determinants. Comput Appl Biosci. 1988;4:181–186. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/4.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido N, Torgov VI, Sugiyama T, Uchiya K, Sugihara H, Komatsu T, et al. Expression of the O9 polysaccharide of Escherichia coli: sequencing of the E. coli O9 rfb gene cluster, characterization of mannosyl transferases, and evidence for an ATP-binding cassette transport system. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2178–2187. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2178-2187.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond P, Fischer G, Francou FX, Berger F, Guerineau M, Decaris B. The unstable region of Streptomyces ambofaciens includes 210 kb terminal inverted repeats flanking the extremities of the linear chromosomal DNA. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:261–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.366894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy EC, Doyle D, Burda K, Corbeil LB, Winter AJ. Superficial antigens of Campylobacter (Vibrio) fetus: characterization of an antiphagocytic component. Infect Immun. 1975;11:517–525. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.3.517-525.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran AP, O’Malley DT, Kosunen TU, Helander IM. Biochemical characterization of Campylobacter fetus lipopolysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3922–3929. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3922-3929.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J, Wren BW, Mungall K, Ketley JM, Churcher C, Basham D, et al. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature. 2000;403:665–668. doi: 10.1038/35001088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Z, Ellison RT, Lewis RV, Blaser MJ. Purification and characterization of a family of high molecular weight surface-array proteins from Campylobacter fetus. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6416–6420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pride DT, Blaser MJ. Concerted evolution between duplicated genetic elements in Helicobacter pylori. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:629–642. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray KC, Tu ZC, Grogono-Thomas R, Newell DG, Thompson SA, Blaser MJ. Campylobacter fetus sap inversion occurs in the absence of RecA function. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5663–5667. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5663-5667.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebald M, Veron M. Teneur en bases de 1’AND et classification des vibrions. Ann Inst Pasteur. 1963;105:897–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirrow MB. Campylobacter and Helicobacter infections of man and animals. In: Parker MT, Collier LH, editors. Principles of Bacteriology, Virology and Immunity. 8th. Vol. 2. London: Edward Arnold; 1990. pp. 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Sleytr UB, Messner P, Sara M. Crystalline bacterial cell surface layers. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:911–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SA, Blaser MJ. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser MJ, editors. Campylobacter. 2nd. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2000. pp. 321–347. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SA, Shedd OL, Ray KC, Beings MH, Jorgensen JP, Blaser MJ. Campylobacter fetus surface layer proteins are transported by a Type I secretion system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6450–6458. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6450-6458.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu ZC, Dewhirst FE, Blaser MJ. Evidence that the Campylobacter fetus sap island is an ancient genomic constituent with origins before mammals and reptiles diverged. Infect Immun. 2001a;68:5663–5667. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2237-2244.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu ZC, Ray KC, Thompson SA, Blaser MJ. Campylobacter fetus uses multiple loci for DNA inversion within the 5′ conserved regions of sap homologs. J Bacteriol. 2001b;183:6654–6661. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6654-6661.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ. Characterization of the Campylobacter fetus sapA promoter: evidence that the sapA promoter is deleted in spontaneous mutant strains. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5916–5922. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5916-5922.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ. Rearrangement of sapA homologs with conserved and variable regions in Campylobacter fetus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7265–7269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SG, Smith SH, Smit J. Isolation and comparison of the paracrystalline surface layer proteins of freshwater Caulobacters. J Bacterial. 1992;174:1783–1792. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1783-1792.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Garcia MM, Blake MS, Pei Z, Blaser MJ. Shift in S-layer protein expression responsible for antigenic variation in Campylobacter fetus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4979–4984. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.4979-4984.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LY, Pei ZH, Fujimoto S, Blaser MJ. Reattachment of surface array proteins to Campylobacter fetus cells. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1258–1267. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1258-1267.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]