“Parenting involves a number of mental health costs, including time, physical and emotional energy, conflicts with other social roles, and the economic burden of childrearing. These hardships are especially salient for women, who are often the primary caretakers of children, and compounded if they are also single parents” (Balaji et al., 2007, p. 1388).

“Women simply worry more about their children. This is largely a social fact…. But there is also a biological explanation: We have evolved to worry” (Shulevitz, 2015).

In basic and applied developmental research on at-risk children and families, I would like to see focused attention on this (too-often rhetorical) question: “Who mothers Mommy?” Being a good enough mother is very hard work. And consistently being a good enough mother to children across a period of decades is a challenging task at best, and one enormously taxing for parents experiencing stressors such as mental illness in the family or prolonged poverty.

Before going any further, let me say that I would wish the same issues to be considered for fathers who are primary caregivers. This essay is in no way intended to minimize the importance of custodial fathers; to the contrary, I believe that their well-being must be considered separately, rather than being assumed to benefit from gender-neutral “parenting interventions” that are designed for and tested with mothers. We cannot assume that what works best for men is the same as what works best for women (Antonucci, Ajrouch, & Birditt, 2013); I will discuss this issue again at the end of this essay, in outlining directions for future work.

Deliberate Attention to Mothering Mothers

Given the charge to state my wish clearly and boldly, here it is: In future prevention efforts, I would like to see front and center, an unambiguous emphasis on ensuring the well-being of those primarily charged with raising the next generation: typically, mothers. This must be done in all “at-risk” groups, defined as individuals who are statistically more likely to show adjustment problems than people in the general population. In the sections that follow, I will describe the threads of evidence that led me to my major recommendation, drawing from research on resilience, recommendations in social policy, and evidence from clinical trials.

Resilience Research

The importance of parents in children’s resilience has been clear in the literature on the topic, ever since the earliest publications in the 1970’s. In pioneering studies by Garmezy, Rutter, Werner and others, the presence of at least one caring adult was commonly noted as very beneficial for children facing adversities.

Around the turn of the century, there was explicit recognition that the family constitutes the single most important environmental influence in children’s resilience as opposed to vulnerability. This conclusion derived from a compendium of articles spanning various life adversities, ranging from serious parental mental illnesses and parent divorce to life in chronic poverty and community violence (Luthar, 2003). Contributing scientists differed greatly in the conceptual frameworks guiding their programmatic research; what they all had in common was long-standing, rigorous attention to children growing up under significant adversities.

Reviewing common themes emerging from these diverse laboratories, the central conclusion was that in terms of relative influence, families are clearly the most important (Luthar & Zelazo, 2003). This conclusion was based in simple logic: Parents are the most proximal influences on children from birth through adulthood; they are the most constant of influences (i.e., more so than particular peers or other adults); the power of parent-child relationships is therefore enormous. In terms of priorities for interventions, accordingly, the central message was that in programs to “foster resilience”, there must always be consideration of the family environment, bolstering positive parenting behaviors among caregivers to the degree possible.

Beyond echoing yet again that “parents matter”, my colleagues and I recently noted the need to consider what bolsters the well-being of parents, with ‘good parenting’ treated as a critical outcome of interest in our research and interventions, and not just a predictor (Luthar, Crossman, & Small, 2015). Developmental science is replete with lists of behaviors that mothers should and should not do, but there has been scant attention to how women might be helped to sustain positive parenting over time, especially when highly stressed themselves. And in terms of likely candidates for significant protective processes, the literature suggests parallels with what has been found in childhood: Just as children need consistent love and support to function well, so do those who must tend them (Luthar et al., 2015). This tending is essential for the sake of the women themselves given the enormity of the decades-long developmental task of motherhood, and for the sake of their children, on whom they wield considerable influence.

Policy Perspectives

The need to support at-risk mothers was long argued by social policy maven, Jane Knitzer, in her longstanding work on children’s mental health (see Knitzer, 2000). Knitzer underscored the importance of relationship-based interventions for mothers trying to raise children in the face of serious adversities, including chronic poverty and psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Again, the logic was simple: if parenting behaviors and everyday functioning are to be improved, the major, generally unmet psychological needs of these mothers must be given concerted attention (Knitzer, 2000).

Over time, Knitzer’s arguments have gained traction in discussions on policy priorities, reflected in recent commentaries. As one example, Shonkoff and Fisher (2013, p. 1645) assert that, “Promoting resilience in young children who experience high levels of adversity depends upon the availability of adults who can help them develop effective coping skills…. Caregivers who are able to provide that buffering protection have sound mental health and well-developed executive function skills in problem solving, planning, monitoring and self-regulation.”

Clinical Trials

In general, psychotherapy trials can provide strong support for theories on whether posited protective processes do in fact bring benefits, and there is, in fact, evidence that if a mother’s well-being is improved, this presages gains across multiple domains of her own functioning and that of children. Historically, perhaps the first parenting intervention to explicitly afford direct attention to the mothers’ emotional well-being (and not just discrete parenting behaviors) is the intervention developed by Alicia Lieberman in the late 1990’s.

Originally developed within a psychoanalytic perspective, Lieberman’s program, called Infant Parent Psychotherapy (IPP) was designed with recognition of the fact that in working with mothers at high risk for maltreating their babies, attention to the women’s own psychological needs is imperative. Contemporary versions of this program (extended for use with mothers and toddlers and young children) bring together treatment approaches based in psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, and social learning theories. A core ingredient, however, remains high empathy and support for the mother, with acknowledgment that “..the most effective interventions are not spoken but rather enacted through the therapist’s empathic attitude and behavior toward the mother as well as the baby (Lieberman and Zeanah, 1999, p. 556). There is a wealth of evidence supporting the benefits of this approach, implemented across diverse settings (see Lieberman, Chu, Van Horn, & Harris, 2011).

Also with direct attention to the personal well-being of at-risk mothers is the Relational Psychotherapy Mothers Group intervention (RPMG; Luthar & Suchman, 2000), developed for mothers at risk for maltreating their children and tested with drug addicted women in methadone maintenance programs. The conceptualization underlying RPMG was similar to that of IPP, with central emphasis on empathy, respect, and insight-oriented (as opposed to didactic) parenting skill facilitation. Additionally, in both interventions, there is explicit acknowledgement of the paucity of role models of “good parenting”, with the female therapist modeling such behaviors.

There were three major differences between RPMG and IPP (and other interventions involving mother-child dyads), all related to pragmatic considerations. First, IPP involves individualized attention to a mother and her child, whereas RPMG is delivered in a group format, thus potentially reaching more women with the same, often limited, resources. Second, in contrast to the focus on infancy and early childhood, RPMG served mothers of children from birth through adolescence, with developmental issues addressed as part of the manualized program and older mothers sharing their experiences with younger ones. Third, children provided pre- and post-assessments but they were never seen themselves in therapy; the latter rendered feasible a group format for mothers of children of diverse ages.

The assumption underlying RPMG was that when a mother achieves positive personal well-being, this becomes “broadly deterministic” with salutary chain reactions triggered across different aspects of her personal adjustment and parenting behaviors. Results of two clinical trials supported this conceptualization. As compared to treatment as usual in their methadone clinics, mothers who received the 24 week intervention showed lower risk for child maltreatment -- by mothers’ and children’s reports -- and better personal adjustment (Luthar & Suchman, 2000). Post-treatment differences were also found for both mothers’ and children’s reports of child maladjustment, and on mothers’ drug use via urinalyses (again, substance abuse was never directly addressed in the intervention). At 6 months post-treatment, RPMG recipients continued to be at an advantage, although the magnitude of group differences was lower.

In the second trial comparing RPMG to alterative treatment groups – relapse prevention therapy (RT) – similar patterns were seen (Luthar, Suchman, & Altomare, 2007). Again, RPMG mothers fared significantly better than RT mothers at the end of treatment, per mothers’ self-reports, children’s reports, and urinalyses. But again, at six months follow-up, they lost many of their gains – sometimes more so than the RT mothers (whose group therapists remained at the clinics when group treatment ended).

Collectively, these findings underscore the need to maintain continuity in supports for mothers even after external interventions cease; this is an idea by no means unique. Consider findings from the widely used, efficacious programs for vulnerable mothers, Olds’ (2007) Nurse-Family Partnership, in which low-income, single mothers are regularly visited at home by a warm, supportive nurse. These visits occur from the prenatal months through the babies’ second birthdays; yet, mothers’ needs for help are not necessarily resolved when home-visiting ends. Recipient mothers report that depression is widespread in their communities, and many would advise depressed friends to seek help -- from a neighbor, family member, or service provider – anyone who has earned their trust through consistent caring over time (Golden, Hawkins, & Beardslee, 2011, p. v).

All this considered, a critical question to be addressed is, how might we ensure continued support for such mothers, allowing them to sustain the substantial gains made through time-limited supportive interventions?

Peer-based Interventions

One model worth considering is based in groups run by peer facilitators, that is, mothers who received supportive programs themselves with subsequent training and supervision (see Bryan & Arkowitz, 2015). This strategy has been used successfully with mothers who had experienced perinatal depression and then met regularly with women currently experiencing this problem. In a meta-analytic review, Bryan and Arkowitz (2015) reported that peer-administered interventions (PAIs) produced substantial reductions in depressive symptoms, with pre-post differences comparable to non-peer-administered interventions, and significantly greater than those in no treatment conditions. Interestingly, PAIs that also involved a professional in treatment (in a secondary role) were less effective than those purely administered by peers.

In future scientific efforts to use such peer-based groups for mothers, we have suggested drawing upon an intervention extensively used for well over half a century and with minimal costs, that is, the 12-step model (see Luthar, Crossman, & Small, 2015). Derived from Alcoholics Anonymous, this program is the currently most commonly sought after source of help for alcohol-related problems, with more than 1.3 million Americans benefiting from weekly meetings (that may be for same-sex individuals or for mixed genders). Echoing findings from research on resilience, a major ‘active ingredient’ in this program is dependable, authentic supports. Powerful benefits are believed to derive from attendees’ shifts to adaptive social networks (e.g., with reductions in pro-drinking friends); members speak of unconditional acceptance in “the rooms,” the absence of shame in sharing their most private failings, and their ability to reach out to others when stressed (for a fuller discussion, please see Luthar et al., 2015).

Given its effectiveness - and again, the fact that it entails low costs – the 12-step model might be used for community-based groups to promote resilience among at-risk mothers. If in fact the power of these meetings does lie largely in the authentic connections forged with others sharing similar struggles, with supportive reminders of their own behaviors that can and should be controlled (versus uncontrollable events), this model could be applied for women vulnerable to troubles in parenting. Continued weekly meetings could help to sustain the type of supportive connections that mothers came to depend upon, in the active phase of relational interventions.

Again, this has been a recurrent theme in prevention and policy: Scientists commonly urge the use of networks that already exist in communities, harnessing them in interventions that can become self-sustaining over time. Within affordable housing complexes, for example, Antonucci and colleagues (2013) describe intervention programs that are focused on increasing people’s awareness of the community around them, and on creating mutually supportive networks among residents. Kazdin and Rabbitt (2013) described several low-cost, feasible, and effective interventions using lay people (rather than professional therapists), including hair stylists in beauty salons, trained to assess depression and to provide appropriate referrals.

Mothering Mothers

At this point in time, my own scientific efforts to promote “mothers being mothered” are focused on piloting a one-hour per week, three-month group intervention for another group of at-risk mothers, that is, physicians with young children. There is a host of reasons for why these women can be highly vulnerable, beginning with their extremely stressful jobs (Shanafelt et al., 2012). Between 30% and 40% of US physicians reportedly experience professional burnout, with women physicians at significantly greater risk than their male counterparts for burnout along with associated problems of depression and emotional exhaustion (Dyrbye et al., 2011). As compared to the general population, male physicians are at 1.1 – 3.4 times greater risk for suicides; among their female counterparts, these rates can be almost six times as high, in the range of 2.5 – 5.7 times the rates among people on average (Bright & Kahn, 2011).

For women physicians in particular, a major factor implicated in burnout is depletion from multiple caregiving responsibilities. Aside from care for patients, these women (like women in general) are generally primary caregivers for their children. Among married/ partnered physicians with children, women spend significantly more time than men on domestic activities, and are over 3 times as likely to take time off when usual child care arrangements are disrupted (Jolly et al., 2014). And as primary caregivers, they are often “first responders” to stressors brought home by their children, who themselves contend with high pressures linked with life in white collar, upwardly mobile communities (Luthar, Barkin, & Crossman, 2013).

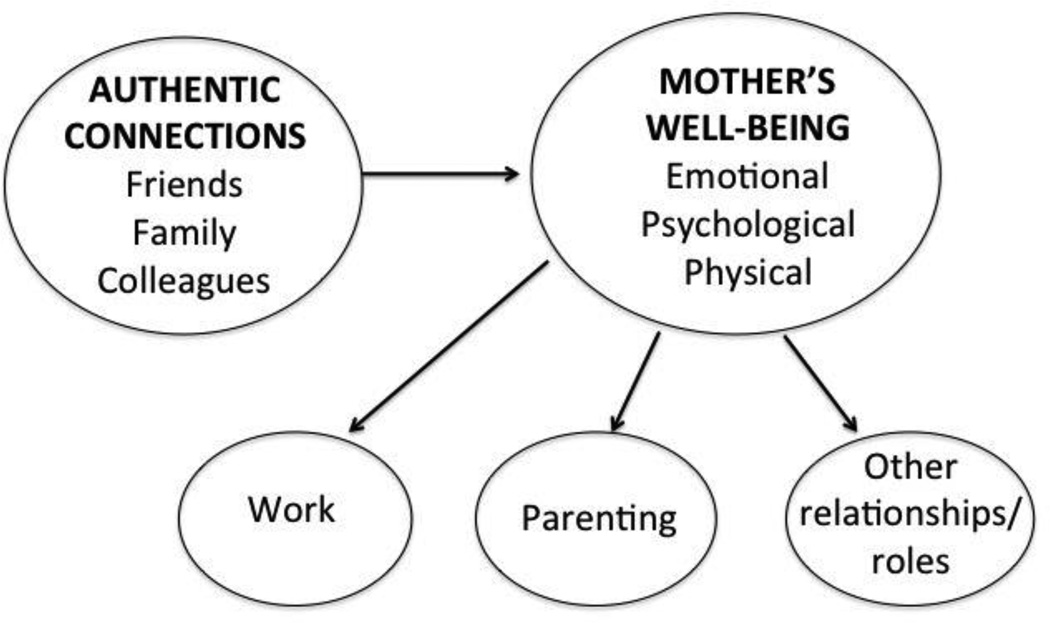

The central conceptualization of the physicians’ intervention, shown in Figure 1, is similar to that underlying RPMG in its emphasis on mothers’ personal well-being, but it differs in ensuring a pointed and resounding emphasis on women’s connectedness with other mothers. From the very first session, a constant refrain is that mothers develop authentic connections not just within the groups (as in RPMG), but more importantly, with other mothers in their everyday lives, who are formally labeled as their “Go-to Committees.”

Figure 1.

Fostering resilience among mothers: Conceptual model of central mechanisms

The pilot trial of this manualized intervention is still underway, but initial reception to the project allows for cautious optimism. To begin with, hospital administrators provided one hour of freed time per week for all physicians to attend the groups, attesting to their beliefs in the need for and value of this program. In the first round of groups, eleven women received the intervention, in two groups of 5 and 6 women respectively. And at the time of this writing, the first round of both groups had been completed, with zero attrition in both cases. Not just did all enrolled women stay in the program through completion (obviously, this was not mandatory), but they unanimously said they would recommend it for other professional mothers, with the following statements exemplifying their perceived value of these groups:

“In an organization where we exemplify “the needs of the patient come first,” it is refreshing and joyful to have a small block of time each day where we can truly take care of our own needs. Professional mothers have such unique needs that can only be understood by other professional mothers, so this group allows you to make a connection that is genuine. You learn that you are not alone in the stress that you feel, how to reduce your guilt/shame in asking for help and focusing on caring for yourself, which in turn takes care of your family.”

“These groups are a beautiful combination of a reflective experience and practical advice. For example, reflecting on the question of having a "Go to committee", versus going to your chosen committee members and verbally and explicitly ask(ing), "Will you be in my committee?" If you feel overwhelmed working, being a mom and wife, you need this. It's not hokey. It speaks to the heart, soul, and for the scientist in all of us--the mind. It just makes sense.”

Future Directions

In considering future directions, I address first what I mentioned at the outset of this essay: the need to develop parenting interventions specifically for men. Scientists with expertise in fatherhood must help to illuminate how at-risk fathers might best be engaged in interventions to bolster their parenting – both as sole caregivers and as co-parents. Prior efforts confirm that what works for fathers can be very different from what works well with mothers. In low-income African-American families, for example, mothers responded well to the “tend and befriend” approach whereas biological fathers were more likely to be recruited via opportunities for enhanced earnings to support their families (Jackson, 2015). In upper middle class settings, similarly, it is unlikely that fathers with time-intensive, high stress jobs will be drawn to weekly groups based in “mutually nurturing, authentic connections” among the men. Thus, there is still much to be learned about how best fathers might be engaged in interventions across diverse socio-demographic settings.

Having said this, I return to the central issue with which I personally remain preoccupied, that is, helping women as they negotiate the challenging job of good- enough-mothering over the course of decades. We cannot assume that mothers’ lapses in parenting behaviors occur because they simply “do not know better” or they do not care. Nor can we assume that mothers need external support only while their children are zero to three or five. Any mother who has raised children from infancy through adulthood has experienced periods of less than optimal parenting; this is a difficult job, with myriad, complex demands, many of which are “moving targets” as children traverse different developmental stages. It is with all this considered that I suggest we make it a top priority to foster the resilience of at-risk mothers, with special efforts to harness what we know from research about women helping other women through adversities.

Summary

In conclusion, I sincerely hope that we in developmental science will come to prioritize mothers being tended and supported in future interventions, preferably in their natural milieus of communities, clinics, and professional settings. Thousands of adults sharing struggles with addiction meet everyday to support each other; there is no reason why women struggling with parenting cannot also meet for shared support, on at least a weekly basis. Toward this end, prevention scientists could help greatly by developing theory-based models of interventions, considering the logistics of different settings, and providing appropriate session outlines as their benefits are established (e.g., Nowinski, Baker, & Carroll, 1999). Over time, it is my earnest wish that women can commonly come to prioritize, and to expect, both giving and receiving of the steadfast love and care that is uniquely associated with the term, “mothering”.

References

- Antonucci T, Arouch KJ, Birditt K. The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. The Gerontologist. 2013;54:82–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji AB, Claussen AH, Smith DC, Visser SN, Morales MJ, Perou R. Social support networks and maternal mental health and well-being. Journal of Women's Health. 2007;16(10):1386–1396. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.CDC10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright RP, Kahn L. Depression and suicide among physicians. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10:16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AE, Arkowitz H. Meta-Analysis of the effects of peer-administered psychosocial interventions on symptoms of depression. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2015;55:455–471. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9718-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Archives of Surgery. 2011;146(2):211–217. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden O, Hawkins A, Bearsdlee W. Home visiting and maternal depression: Seizing the opportunities to help mothers and young children. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/research/publication/home-visiting-and-maternal-depression-seizing-opportunities-help-mothers-and. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. Strategies for supporting low-income and welfare-dependent parents of young children. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/Activities/Children/CommitteeonSupportingtheParentsofYoungChildren/2015-APR-09/Videos/8-Jackson-Video.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160:344–353. doi: 10.7326/M13-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knitzer J. Early childhood mental health services: A policy and systems development perspective. In: Shonkoff JP, Meisels SJ, editors. Handbook of early childhood intervention. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 416–438. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Chu A, Van Horn P, Harris W. Trauma in early childhood: Empirical evidence and clinical implications. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:397–410. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Zeanah CH. Contributions of attachment theory to infant–parent psychotherapy and other interventions with infants and young children. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 555–574. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Barkin SH, Crossman EJ. “I can, therefore I must”: Fragility in the upper-middle classes. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:1529–1549. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000758. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Crossman EJ, Small PJ. Resilience and adversity. In: Lerner RM, Lamb ME, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science. 7th. III. New York: Wiley; 2015. pp. 247–286. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Suchman NE. Relational Psychotherapy Mothers’ Group: A developmentally informed intervention for at-risk mothers. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:235–253. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002078. PMC3313648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Suchman NE, Altomare M. Relational Psychotherapy Mothers Group: A randomized clinical trial for substance abusing mothers. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:243–261. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070137. PMC2190295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowinski J, Baker S, Carroll K. The Twelve Step Facilitation Therapy Manual. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, Oreskovich MR. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172:1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulevitz J. [Retrieved on May 10, 2015];Mom: The designated worrier. 2015 from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/10/opinion/sunday/judith-shulevitz-mom-the-designated-worrier.html?_r=2. [Google Scholar]